This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 19,000 words. (June 2023) |

New Mexico (Spanish: Nuevo México[Note 2][7] [ˈnweβo ˈmexiko] ; Navajo: Yootó Hahoodzo Navajo pronunciation: [jòːtʰó hɑ̀hòːtsò]) is a state in the Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also borders the state of Texas to the east and southeast, Oklahoma to the northeast, and shares an international border with the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora to the south. New Mexico's largest city is Albuquerque, and its state capital is Santa Fe, the oldest state capital in the U.S., founded in 1610 as the government seat of Nuevo México in New Spain.

New Mexico

| |

|---|---|

| State of New Mexico Estado de Nuevo México (Spanish) | |

| Nickname: The Land of Enchantment | |

| Motto: Crescit eundo (It grows as it goes) | |

Anthem:

| |

Map of the United States with New Mexico highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood |

|

| Admitted to the Union | January 6, 1912 (47th) |

| Capital | Santa Fe |

| Largest city | Albuquerque |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Albuquerque metropolitan area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Howie Morales (D) |

| Legislature | New Mexico Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | New Mexico Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators |

|

| U.S. House delegation |

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 121,591[1] sq mi (314,915 km2) |

| • Land | 121,298[1] sq mi (314,161 km2) |

| • Water | 292[1] sq mi (757 km2) 0.24% |

| • Rank | 5th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 371 mi (596 km) |

| • Width | 344 mi (552 km) |

| Elevation | 5,701 ft (1,741 m) |

| Highest elevation | 13,161 ft (4,011.4 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 2,845 ft (868 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 2,117,522 |

| • Rank | 36th |

| • Density | 17.2/sq mi (6.62/km2) |

| • Rank | 45th |

| • Median household income | $51,945 |

| • Income rank | 45th |

| Demonym(s) | New Mexican (Spanish: Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)[4] |

| Language | |

| • Official language | None |

| • Spoken language | English, Spanish (New Mexican), Navajo, Keres, Zuni[5] |

| Time zone | UTC– 07:00 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC– 06:00 (MDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | NM |

| ISO 3166 code | US-NM |

| Traditional abbreviation | N.M., N.Mex. |

| Latitude | 31°20′ N to 37°N |

| Longitude | 103° W to 109°3′ W |

| Website | nm |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Greater roadrunner |

| Fish | Rio Grande cutthroat trout |

| Flower | Yucca |

| Grass | Blue grama |

| Insect | Tarantula Hawk Wasp |

| Mammal | American black bear |

| Reptile | New Mexico whiptail |

| Tree | Two-needle piñon |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Color(s) | Red and yellow |

| Food | Chile peppers, pinto beans, and biscochitos |

| Fossil | Coelophysis |

| Gemstone | Turquoise |

| Other | The smell of roasting green chile[6] |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2008 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

New Mexico is the fifth-largest of the fifty states by area, but with just over 2.1 million residents, ranks 36th in population and 45th in population density.[8] Its climate and geography are highly varied, ranging from forested mountains to sparse deserts; the northern and eastern regions exhibit a colder alpine climate, while the west and south are warmer and more arid. The Rio Grande and its fertile valley runs from north-to-south, creating a riparian climate through the center of the state that supports a bosque habitat and distinct Albuquerque Basin climate. One-third of New Mexico's land is federally owned, and the state hosts many protected wilderness areas and national monuments, including three UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the most of any U.S. state.[9]

New Mexico's economy is highly diversified, including cattle ranching, agriculture, lumber, scientific and technological research, tourism, and the arts; major sectors include mining, oil and gas, aerospace, media, and film.[10][11][12][13] Its total gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 was $95.73 billion, with a GDP per capita of roughly $46,300.[14][15] State tax policy is characterized by low to moderate taxation of resident personal income by national standards, with tax credits, exemptions, and special considerations for military personnel and favorable industries. New Mexico has a significant U.S. military presence,[16] including White Sands Missile Range, and strategically valuable federal research centers, such as the Sandia and Los Alamos National Laboratories. The state hosted several key facilities of the Manhattan Project, which developed the world's first atomic bomb, and was the site of the first nuclear test, Trinity.

In prehistoric times, New Mexico was home to Ancestral Puebloans, the Mogollon culture, and ancestral Ute.[17] Navajos and Apaches arrived in the late 15th century and the Comanches in the early 18th century. The Pueblo peoples occupied several dozen villages, primarily in the Rio Grande valley of northern New Mexico.[18][19] Spanish explorers and settlers arrived in the 16th century from present-day Mexico.[20][21][22] Isolated by its rugged terrain, New Mexico was a peripheral part of the viceroyalty of New Spain dominated by Comancheria. Following Mexican independence in 1821, it became an autonomous region of Mexico, albeit increasingly threatened by the centralizing policies of the Mexican government, culminating in the Revolt of 1837; at the same time, the region became more economically dependent on the U.S. Following the Mexican–American War in 1848, the U.S. annexed New Mexico as part of the larger New Mexico Territory. It played a central role in U.S. westward expansion and was admitted to the Union as the 47th state on January 6, 1912.

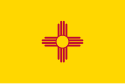

New Mexico's history has contributed to its unique demographic and cultural character. It is one of only seven majority-minority states, with the nation's highest percentage of Hispanic and Latino Americans and the second-highest percentage of Native Americans, after Alaska.[23] The state is home to one–third of the Navajo Nation, 19 federally recognized Pueblo communities, and three federally recognized Apache tribes. Its large Hispanic population includes Hispanos descended from settlers during the Spanish era,[24][25] and later groups of Mexican Americans since the 19th century. The New Mexican flag, which is among the most recognizable in the U.S.,[26] reflects the state's eclectic origins, featuring the ancient sun symbol of the Zia, a Puebloan tribe, with the scarlet and gold coloration of the Spanish flag.[27] The confluence of indigenous, Hispanic (Spanish and Mexican), and American influences is also evident in New Mexico's unique cuisine, music genre, and architectural styles.

Etymology

editNew Mexico received its name long before the present-day country of Mexico won independence from Spain and adopted that name in 1821. The name "Mexico" derives from Nahuatl and originally referred to the heartland of the Mexica, the rulers of the Aztec Empire, in the Valley of Mexico.[28][29] Following their conquest of the Aztecs in the early 16th century, the Spanish began exploring what is now the Southwestern United States calling it Nuevo México. In 1581, the Chamuscado and Rodríguez Expedition named the region north of the Rio Grande San Felipe del Nuevo México.[30] The Spaniards had hoped to find wealthy indigenous cultures similar to the Mexica. The indigenous cultures of New Mexico, however, proved to be unrelated to the Mexica and lacking in riches, but the name persisted.[31][32]

Before statehood in 1912, the name "New Mexico" loosely applied to various configurations of territories in the same general area, which evolved throughout the Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. periods, but typically encompassed most of present-day New Mexico along with sections of neighboring states.[33]

History

editPrehistory

editThe first known inhabitants of New Mexico were members of the Clovis culture of Paleo-Indians.[34]: 19 Footprints discovered in 2017 suggest that humans may have been present in the region as long ago as 21,000–23,000 BC.[35] Later inhabitants include the Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo cultures, which are characterized by sophisticated pottery work and urban development;[36]: 52 pueblos or their remnants, like those at Acoma, Taos, and Chaco Culture National Historical Park, indicate the scale of Ancestral Puebloan dwellings within the area. These cultures form part of the broader Oasisamerica region of pre-Columbian North America.

The vast trade networks of the Ancestral Puebloans led to legends throughout Mesoamerica and the Aztec Empire (Mexico) of an unseen northern empire that rivaled their own, which they called Yancuic Mexico, literally translated as "a new Mexico".

Nuevo México

editNew Spain era

editAztec legends of a prosperous empire to their north became the primary basis for the mythical Seven Cities of Gold, which spurred exploration by Spanish conquistadors following their conquest of the Aztecs in the early 16th century; prominent explorers included Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Estevanico, and Marcos de Niza.

The settlement of La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asís — modern day Santa Fe – was established by Pedro de Peralta as a more permanent capital at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in 1610.[37]: 182 Towards the end of the 17th century, the Pueblo Revolt drove out the Spanish and occupied these early cities for over a decade.[38] After the death of Pueblo leader Popé, Diego de Vargas restored the area to Spanish rule,[36]: 68–75 with Puebloans offered greater cultural and religious liberties.[39][40][34]: 6, 48 Returning settlers founded La Villa de Alburquerque in 1706 at Old Town Albuquerque as a trading center for existing surrounding communities such as Barelas, Isleta, Los Ranchos, and Sandia;[36]: 84 it was named for the viceroy of New Spain, Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, 10th Duke of Alburquerque.[41] Governor Francisco Cuervo y Valdés established the villa in Tiguex to provide free trade access and facilitate cultural exchange in the region.

Beyond forging better relations with the Pueblos, governors were forbearing in their approach to the indigenous peoples, such as was with governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín;[42] the comparatively large reservations in New Mexico and Arizona are partly a legacy of Spanish treaties recognizing indigenous land claims in Nuevo México.[43] Nevertheless, relations between the various indigenous groups and Spanish settlers remained nebulous and complex, varying from trade and commerce to cultural assimilation and intermarriage to total warfare. During most of the 18th century, raids by Navajo, Apache, and especially Comanche inhibited the growth and prosperity of the New Mexico. The region's harsh environment and remoteness, surrounded by hostile Native Americans, fostered a greater degree of self-reliance, as well as pragmatic cooperation, between the Pueblo peoples and colonists. Many indigenous communities enjoyed a large measure of autonomy well into the late 19th century due to the improved governance.

To encourage settlement in its vulnerable periphery, Spain awarded land grants to European settlers in Nuevo México; due to the scarcity of water throughout the region, the vast majority of colonists resided in the central valley of the Rio Grande and its tributaries. Most communities were walled enclaves consisting of adobe houses that opened onto a plaza, from which four streets ran outward to small, private agricultural plots and orchards; these were watered by acequias, community owned and operated irrigation canals. Just beyond the wall was the ejido, communal land for grazing, firewood, or recreation. By 1800, the population of New Mexico had reached 25,000 (not including indigenous inhabitants), far exceeding the territories of California and Texas.[44]

Mexico era

editAs part of New Spain, the province of New Mexico became part of the First Mexican Empire in 1821 following the Mexican War of Independence.[36]: 109 Upon its secession from Mexico in 1836, the Republic of Texas claimed the portion east of the Rio Grande, based on the erroneous assumption that the older Hispanic settlements of the upper Rio Grande were the same as the newly established Mexican settlements of Texas. The Texan Santa Fe Expedition was launched to seize the contested territory but failed with the capture and imprisonment of the entire army by the Hispanic New Mexico militia.

During the turn of the 19th century, the extreme northeastern part of New Mexico, north of the Canadian River and east of the spine of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, was still claimed by France, which sold it in 1803 as part of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1812, the U.S. reclassified the land as part of the Missouri Territory. This region of New Mexico (along with territory comprising present-day southeastern Colorado, the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles, and southwestern Kansas) was ceded to Spain under the Adams-Onis Treaty in 1819.

When the First Mexican Republic began to transition into the Centralist Republic of Mexico, they began to centralize power ignoring the sovereignty of Santa Fe and disregarding Pueblo land rights. This led to the Chimayó Rebellion in 1837, led by genízaro José Gonzales.[45] The death of then governor Albino Pérez during the revolt, was met with further hostility. Though José Gonzales was executed due to his involvement in the governor's death, subsequent governors Manuel Armijo and Juan Bautista Vigil y Alarid agreed with some of the underlying sentiment. This led to New Mexico becoming financially and politically tied to the U.S., and preferring trade along the Santa Fe Trail.

Territorial phase

editFollowing the victory of the United States in the Mexican–American War (1846–48), Mexico ceded its northern territories to the U.S., including California, Texas, and New Mexico.[36]: 132 The Americans were initially heavy-handed in their treatment of former Mexican citizens, triggering the Taos Revolt in 1847 by Hispanos and their Pueblo allies; the insurrection led to the death of territorial governor Charles Bent and the collapse of the civilian government established by Stephen W. Kearny. In response, the U.S. government appointed local Donaciano Vigil as governor to better represent New Mexico,[46] and also vowed to accept the land rights of Nuevomexicans and grant them citizenship. In 1864, President Abraham Lincoln symbolized the recognition of Native land rights with the Lincoln Canes, sceptres of office gifted to each of the Pueblos, a tradition dating back to Spanish and Mexican eras.[47][48]

After the Republic of Texas was admitted as a state in 1846, it attempted to claim the eastern portion of New Mexico east of the Rio Grande, while the California Republic and State of Deseret each claimed parts of western New Mexico. Under the Compromise of 1850, these regions were forced by the U.S. government to drop their claims, Texas received $10 million in federal funds, California was granted statehood, and officially establishing the Utah Territory; therein recognizing most of New Mexico's historically established land claims.[36]: 135 Pursuant to the compromise, Congress established the New Mexico Territory in September of that year;[49] it included most of present-day Arizona and New Mexico, along with the Las Vegas Valley and what would later become Clark County in Nevada.

In 1853 the U.S. acquired the mostly desert southwestern bootheel of the state, along with Arizona's land south of the Gila River, in the Gadsden Purchase, which was needed for the right-of-way to encourage construction of a transcontinental railroad.[36]: 136

U.S. Civil War, American Indian Wars, and American frontier

editWhen the U.S. Civil War broke out in 1861, both Confederate and Union governments claimed ownership and territorial rights over New Mexico Territory. The Confederacy claimed the southern tract as its own Arizona Territory, and as part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the war, waged the ambitious New Mexico Campaign to control the American Southwest and open up access to Union California. Confederate power in the New Mexico Territory was effectively broken after the Battle of Glorieta Pass in 1862, though the Confederate territorial government continued to operate out of Texas. More than 8,000 soldiers from New Mexico Territory served in the Union Army.[50]

The end of the war saw rapid economic development and settlement in New Mexico, which attracted homesteaders, ranchers, cowboys, businessmen, and outlaws;[51] many of the folklore characters of the Western genre had their origins in New Mexico, most notably businesswoman Maria Gertrudis Barceló, outlaw Billy the Kid, and lawmen Pat Garrett and Elfego Baca. The influx of "Anglo Americans" from the eastern U.S. (which include African Americans and recent European immigrants) reshaped the state's economy, culture, and politics. Into the late 19th century, the majority of New Mexicans remained ethnic mestizos of mixed Spanish and Native American ancestry (primarily Pueblo, Navajo, Apache, Genízaro, and Comanche), many of whom had roots going back to Spanish settlement in the 16th century; this distinctly New Mexican ethnic group became known as Hispanos and developed a more pronounced identity vis-a-vis the newer Anglo arrivals. Politically, they still controlled most town and county offices through local elections, and wealthy ranching families commanded considerable influence, preferring business, legislative, and judicial relations with fellow indigenous New Mexican groups. By contrast, Anglo Americans, who were "outnumbered, but well-organized and growing"[52] tended to have more ties to the territorial government, whose officials were appointed by the U.S. federal government; subsequently, newer residents of New Mexico generally favored maintaining territorial status, which they saw as a check on Native and Hispano influence.

A consequence of the civil war was intensifying conflict with indigenous peoples, which was part of the broader American Indian Wars along the frontier. The withdrawal of troops and material for the war effort had prompted raids by hostile tribes, and the federal government moved to subdue the many native communities that had been effectively autonomous throughout the colonial period. Following the elimination of the Confederate threat, Brigadier General James Carleton, who had assumed command of the Military Department of New Mexico in 1862, led what he described as a "merciless war against all hostile tribes" that aimed to "force them to their knees, and then confine them to reservations where they could be Christianized and instructed in agriculture."[51] With famed frontiersman Kit Carson placed in charge of troops in the field, powerful indigenous groups such as the Navajo, Mescalero Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche were brutally pacified through a scorched earth policy, and thereafter forced into barren and remote reservations. Sporadic conflicts continued into the late 1880s, most notably the guerilla campaigns led by Apache chiefs Victorio and his son-in-law Nana.

The political and cultural clashes between these competing ethnic groups sometimes culminated in mob violence, including lynchings of Native, Hispanic, and Mexican peoples, as was attempted at the Frisco shootout in 1884. Nevertheless, prominent figures from across these communities, and from both the Democratic and Republican parties, attempted to fight this prejudice and forge a more cohesive, multiethnic New Mexican identity; they include lawmen Baca and Garrett, and governors Curry, Hagerman, and Otero.[53][54] Indeed, some territorial governors, like Lew Wallace, had served in both the Mexican and American militaries.[55]

Statehood

editThe United States Congress admitted New Mexico as the 47th state on January 6, 1912.[36]: 166 It had been eligible for statehood 60 years earlier, but was delayed due to the perception that its majority Hispanic population was "alien" to U.S. culture and political values.[56] When the U.S. entered the First World War roughly five years later, New Mexicans volunteered in significant numbers, in part to prove their loyalty as full-fledged citizens of the U.S. The state ranked fifth in the nation for military service, enlisting more than 17,000 recruits from all 33 counties; over 500 New Mexicans were killed in the war.[57]

Indigenous-Hispanic families had long been established since the Spanish and Mexican era,[58] but most American settlers in the state had an uneasy relationship with the large Native American tribes.[59] Most indigenous New Mexicans lived on reservations and near old placitas and villas. In 1924, Congress passed a law granting all Native Americans U.S. citizenship and the right to vote in federal and state elections. However, Anglo-American arrivals into New Mexico enacted Jim Crow laws against Hispanos, Hispanic Americans, and those who did not pay taxes, targeting indigenous affiliated individuals;[60] because Hispanics often had interpersonal relationships with indigenous peoples, they were often subject to segregation, social inequality, and employment discrimination.[59]

During the fight for women's suffrage in the United States, New Mexico's Hispano and Mexican women at the forefront included Trinidad Cabeza de Baca, Dolores "Lola" Armijo, Mrs. James Chavez, Aurora Lucero, Anita "Mrs. Secundino" Romero, Arabella "Mrs. Cleofas" Romero and her daughter, Marie.[61][62]

A major oil discovery in 1928 near the town of Hobbs brought greater wealth to the state, especially in surrounding Lea County.[63] The New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources called it "the most important single discovery of oil in New Mexico's history".[64] Nevertheless, agriculture and cattle ranching remained the primary economic activities.

New Mexico was greatly transformed by the U.S. entry into the Second World War in December 1941. As in the First World War, patriotism ran high among New Mexicans, including among marginalized Hispanic and indigenous communities; on a per capita basis, New Mexico produced more volunteers, and suffered more casualties, than any other state. The war also spurred economic development, particularly in extractive industries, with the state becoming a leading supplier of several strategic resources. New Mexico's rough terrain and geographic isolation made it an attractive location for several sensitive military and scientific installations; the most famous was Los Alamos, one of the central facilities of the Manhattan Project, where the first atomic bombs were designed and manufactured. The first bomb was tested at Trinity site in the desert between Socorro and Alamogordo, which is today part of the White Sands Missile Range.[36]: 179–180

As a legacy of the Second World War, New Mexico continues to receive large amounts of federal government spending on major military and research institutions. In addition to the White Sands Missile Range, the state hosts three U.S. Air Force bases that were established or expanded during the war. While the high military presence brought considerable investment, it has also been the center of controversy; on May 22, 1957, a B-36 accidentally dropped a nuclear bomb 4.5 miles from the control tower while landing at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque; only its conventional "trigger" detonated.[65][66] The Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratories, two of the nation's leading federal scientific research facilities, originated from the Manhattan Project. The focus on high technology is still a top priority of the state, to the extent that it became a center for unidentified flying objects, especially following the 1947 Roswell incident.

New Mexico saw its population nearly double from roughly 532,000 in 1940 to over 954,000 by 1960.[67][68] In addition to federal personnel and agencies, many residents and businesses moved to the state, particularly from the northeast, often drawn by its warm climate and low taxes.[69] The pattern continues into the 21st century, with New Mexico adding over 400,000 residents between 2000 and 2020.

Native Americans from New Mexico fought for the United States in both world wars. Returning veterans were disappointed to find their civil rights limited by state discrimination. In Arizona and New Mexico, veterans challenged state laws or practices prohibiting them from voting. In 1948, after veteran Miguel Trujillo Sr. of Isleta Pueblo was told by the county registrar that he could not register to vote, he filed suit against the county in federal district court. A three-judge panel overturned as unconstitutional New Mexico's provisions that Native Americans who did not pay taxes (and could not document if they had paid taxes) could not vote.[60][Note 3]

In the early to mid-20th century, the art presence in Santa Fe grew, and it became known as one of the world's great art centers.[70] The presence of artists such as Georgia O'Keeffe attracted many others, including those along Canyon Road.[71] In the late 20th century, Native Americans were authorized by federal law to establish gaming casinos on their reservations under certain conditions, in states which had authorized such gaming. Such facilities have helped tribes close to population centers generate revenues for reinvestment in the economic development and welfare of their peoples. The Albuquerque metropolitan area is home to several casinos as a result.[72]

In the 21st century, employment growth areas in New Mexico include electronic circuitry, scientific research, information technology, casinos, art of the American Southwest, food, film, and media, particularly in Albuquerque.[73] The state was the founding location of Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems, which led to the founding of Microsoft in Albuquerque.[74] Intel maintains their F11X in Rio Rancho, which also hosts an IT center for HP Inc.[75][76] New Mexico's culinary scene became recognized and is now a source of revenue for the state.[77][78][79] Albuquerque Studios has become a filming hub for Netflix, and it was brought international media production companies to the state like NBCUniversal.[80][81][82]

The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached the U.S. state of New Mexico on March 11, 2020. On December 23, 2020, the New Mexico Department of Health reported 1,174 new COVID-19 cases and 40 deaths, bringing the cumulative statewide totals to 133,242 cases and 2,243 deaths since the start of the pandemic.[83]

Geography

editWith a total area of 121,590 square miles (314,900 km2),[1] New Mexico is the fifth-largest state, after Alaska, Texas, California, and Montana. Its eastern border lies along 103°W longitude with the state of Oklahoma, and 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometres) west of 103°W longitude with Texas due to a 19th-century surveying error.[84][85] On the southern border, Texas makes up the eastern two-thirds, while the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora make up the western third, with Chihuahua making up about 90% of that. The western border with Arizona runs along the 109° 03'W longitude.[86] The southwestern corner of the state is known as the Bootheel. The 37°N parallel forms the northern boundary with Colorado. The states of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah come together at the Four Corners in New Mexico's northwestern corner. Its surface water area is about 292 square miles (760 km2).[1]

Despite its popular depiction as mostly arid desert, New Mexico has one of the most diverse landscapes of any U.S. state, ranging from wide, auburn-colored deserts and verdant grasslands, to broken mesas and high, snow-capped peaks.[87] Close to a third of the state is covered in timberland, with heavily forested mountain wildernesses dominating the north. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the southernmost part of the Rocky Mountains, run roughly north–south along the east side of the Rio Grande, in the rugged, pastoral north. The Great Plains extend into the eastern third of the state, most notably the Llano Estacado ("Staked Plain"), whose westernmost boundary is marked by the Mescalero Ridge escarpment. The northwestern quadrant of New Mexico is dominated by the Colorado Plateau, characterized by unique volcanic formations, dry grasslands and shrublands, open pinyon-juniper woodland, and mountain forests.[88] The Chihuahuan Desert, which is the largest in North America, extends through the south.

Over four–fifths of New Mexico is higher than 4,000 feet (1,200 meters) above sea level. The average elevation ranges from up to 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) above sea level in the northwest, to less than 4,000 feet in the southeast.[87] The highest point is Wheeler Peak at over 13,160 feet (4,010 meters) in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, while the lowest is the Red Bluff Reservoir at around 2,840 feet (870 meters), in the southeastern corner of the state.

In addition to the Rio Grande, which is tied for the fourth-longest river in the U.S., New Mexico has four other major river systems: the Pecos, Canadian, San Juan, and Gila.[89] Nearly bisecting New Mexico from north to south, the Rio Grande has played an influential role in the region's history; its fertile floodplain has supported human habitation since prehistoric times, and European settlers initially lived exclusively in its valleys and along its tributaries.[87] The Pecos, which flows roughly parallel to the Rio Grande at its east, was a popular route for explorers, as was the Canadian River, which rises in the mountainous north and flows east across the arid plains. The San Juan and Gila lie west of the Continental Divide, in the northwest and southwest, respectively. With the exception of the Gila, all major rivers are dammed in New Mexico and provide a major water source for irrigation and flood control.

Climate

editNew Mexico has long been known for its dry, temperate climate.[87] Overall the state is semi-arid to arid, with areas of continental and alpine climates at higher elevations. New Mexico's statewide average precipitation is 13.7 inches (350 mm) a year, with average monthly amounts peaking in the summer, particularly in the more rugged north-central area around Albuquerque and in the south. Generally, the eastern third of the state receives the most rainfall, while the western third receives the least. Higher altitudes receive around 40 inches (1,000 mm), while the lowest elevations see as little as 8 to 10 inches (200 to 250 millimetres).[87]

| Climate data for New Mexico | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 89 (32) |

100 (38) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

122 (50) |

116 (47) |

115 (46) |

113 (45) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

90 (32) |

122 (50) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 49.7 (9.8) |

54.0 (12.2) |

61.8 (16.6) |

69.2 (20.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

87.8 (31.0) |

88.8 (31.6) |

86.3 (30.2) |

80.4 (26.9) |

70.6 (21.4) |

58.6 (14.8) |

49.4 (9.7) |

69.6 (20.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 21.7 (−5.7) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

36.5 (2.5) |

45.2 (7.3) |

54.4 (12.4) |

59.5 (15.3) |

58.1 (14.5) |

51.1 (10.6) |

39.7 (4.3) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

22.0 (−5.6) |

39.4 (4.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −57 (−49) |

−50 (−46) |

−34 (−37) |

−36 (−38) |

−2 (−19) |

10 (−12) |

19 (−7) |

23 (−5) |

8 (−13) |

−15 (−26) |

−38 (−39) |

−47 (−44) |

−57 (−49) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.67 (17) |

0.59 (15) |

0.69 (18) |

0.62 (16) |

0.91 (23) |

1.02 (26) |

2.44 (62) |

2.33 (59) |

1.76 (45) |

1.17 (30) |

0.68 (17) |

0.81 (21) |

13.69 (349) |

| Source 1: Extreme Weather Watch[90] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[91] | |||||||||||||

Annual temperatures can range from 65 °F (18 °C) in the southeast to below 40 °F (4 °C) in the northern mountains,[86] with the average being the mid-50s °F (12 °C). During the summer, daytime temperatures can often exceed 100 °F (38 °C) at elevations below 5,000 feet (1,500 m); the average high temperature in July ranges from 99 °F (37 °C) at the lower elevations down to 78 °F (26 °C) at the higher elevations. In the colder months of November to March, many cities in New Mexico can have nighttime temperature lows in the teens above zero, or lower. The highest temperature recorded in New Mexico was 122 °F (50 °C) at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) near Loving on June 27, 1994; the lowest recorded temperature is −57 °F (−49 °C) at Ciniza (near Jamestown) on January 13, 1963.[92]

New Mexico's stable climate and sparse population provides for clearer skies and less light pollution, making it a popular site for several major astronomical observatories, including the Apache Point Observatory, the Very Large Array, and the Magdalena Ridge Observatory, among others.[93][94]

Flora and fauna

editOwing to its varied topography, New Mexico has six distinct vegetation zones that provide diverse sets of habitats for many plants and animals.[95] The Upper Sonoran Zone is by far the most prominent, constituting about three-fourths of the state; it includes most of the plains, foothills, and valleys above 4,500 feet, and is defined by prairie grasses, low piñon pines, and juniper shrubs. The Llano Estacado in the east features Shortgrass Prairie with blue grama, which sustain bison. The Chihuahuan Desert in the south is characterized by shrubby creosote. The Colorado Plateau in the northwest corner of New Mexico is high desert with cold winters, featuring sagebrush, shadescale, greasewood, and other plants adapted to the saline and seleniferous soil.

The mountainous north hosts a wide array of vegetation types corresponding to elevation gradients, such as piñon-juniper woodlands near the base, through evergreen conifers, spruce-fir and aspen forests in the transitionary zone, and Krummholz, and alpine tundra at the very top.[95] The Apachian zone tucked into the southwestern bootheel of the state has high-calcium soil, oak woodlands, Arizona cypress, and other plants that are not found in other parts of the state.[96][97] The southern sections of the Rio Grande and Pecos valleys have 20,000 square miles (52,000 square kilometres) of New Mexico's best grazing land and irrigated farmland.

New Mexico's varied climate and vegetation zones consequently support diverse wildlife. Black bears, bighorn sheep, bobcats, cougars, deer, and elk live in habitats above 7,000 feet, while coyotes, jackrabbits, kangaroo rats, javelina, porcupines, pronghorn antelope, western diamondbacks, and wild turkeys live in less mountainous and elevated regions.[98][99][100] The iconic roadrunner, which is the state bird, is abundant in the southeast. Endangered species include the Mexican gray wolf, which is being gradually reintroduced in the world, and Rio Grande silvery minnow.[101] Over 500 species of birds live or migrate through New Mexico, third only to California and Mexico.[102]

Conservation

editNew Mexico and 12 other western states together account for 93% of all federally owned land in the U.S. Roughly one–third of the state, or 24.7 million of 77.8 million acres, is held by the U.S. government, the tenth-highest percentage in the country. More than half this land is under the Bureau of Land Management as either public domain land or National Conservation Lands, while another third is managed by the U.S. Forest Service as national forests.[103]

New Mexico was central to the early–20th century conservation movement, with Gila Wilderness being designated the world's first wilderness area in 1924.[104] The state also hosts nine of the country's 84 national monuments, the most of any state after Arizona; these include the second oldest monument, El Morro, which was created in 1906, and the Gila Cliff Dwellings, proclaimed in 1907.[104]

National forests in New Mexico

edit| Carson National Forest | |

| Cibola National Forest | |

| Lincoln National Forest | |

| Santa Fe National Forest | |

| Gila National Forest | |

| Gila Wilderness | |

| Coronado National Forest (in Hidalgo County) |

National parks in New Mexico

editNew Mexico's national parks, together with national monuments and trails managed by the National Park Service, are listed as follows:[105]

- Aztec Ruins National Monument at Aztec

- Bandelier National Monument at White Rock

- Butterfield Overland National Historic Trail

- Capulin Volcano National Monument near Capulin

- Carlsbad Caverns National Park near Carlsbad

- Chaco Culture National Historical Park at Nageezi

- El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail

- El Malpais National Monument near Grants

- El Morro National Monument in Ramah

- Fort Union National Monument at Watrous

- Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument near Silver City

- Manhattan Project National Historical Park in Los Alamos

- Old Spanish National Historic Trail

- Pecos National Historical Park in Pecos

- Petroglyph National Monument near Albuquerque

- Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument at Mountainair

- Santa Fe National Historic Trail

- Valles Caldera National Preserve in the Jemez Mountains

- White Sands National Park near Alamogordo

National conservation lands in New Mexico

editNew Mexico's national monuments, conservation areas, and other units of the National Landscape Conservation System are managed by the Bureau of Land Management. Units include but are not limited to:[106]

- Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness near Farmington

- El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail

- El Malpais National Conservation Area near Grants

- Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument in Cochiti Pueblo

- Prehistoric Trackways National Monument near Las Cruces

- Old Spanish National Historic Trail

- Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument near Las Cruces

- Rio Grande del Norte National Monument near Taos

- Rio Chama Wild and Scenic River near Abiquiu

- Rio Grande and Red River Wild and Scenic Rivers near Questa

National wildlife refuges in New Mexico

editNew Mexico's National Wildlife Refuges are managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Units include:

- Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge

- Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge

- Grulla National Wildlife Refuge

- Las Vegas National Wildlife Refuge

- Maxwell National Wildlife Refuge

- San Andres National Wildlife Refuge

- Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge

- Valle de Oro National Wildlife Refuge

State parks in New Mexico

editAreas managed by the New Mexico State Parks Division:[107][Note 4]

- Bluewater Lake State Park

- Bottomless Lakes State Park

- Brantley Lake State Park

- Cerrillos Hills State Park

- Caballo Lake State Park

- Cimarron Canyon State Park

- City of Rocks State Park

- Clayton Lake State Park

- Conchas Lake State Park

- Coyote Creek State Park

- Eagle Nest Lake State Park

- Elephant Butte Lake State Park

- El Vado Lake State Park

- Heron Lake State Park

- Hyde Memorial State Park

- Leasburg Dam State Park

- Living Desert Zoo and Gardens State Park

- Manzano Mountains State Park

- Mesilla Valley Bosque State Park

- Morphy Lake State Park

- Navajo Lake (Rio Arriba, NM and San Juan, NM)

- Oasis State Park

- Oliver Lee Memorial State Park

- Pancho Villa State Park

- Percha Dam State Park

- Rio Grande Nature Center State Park

- Rio Grande Valley State Park

- Rockhound State Park

- Santa Rosa Lake State Park

- Storrie Lake State Park

- Sugarite Canyon State Park

- Sumner Lake State Park

- Fenton Lake State Park

- Ute Lake State Park

- Villanueva State Park

Other nature reserves in New Mexico

editExamples of locally administered nature reserves include:

- Whitfield Wildlife Conservation Area in Valencia County[108][109]

- Albuquerque Open Space, see Open Space Visitor Center[110]

Environmental issues

editIn January 2016, New Mexico sued the United States Environmental Protection Agency over negligence after the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill. The spill had caused heavy metals such as cadmium and lead and toxins such as arsenic to flow into the Animas River, polluting water basins of several states.[111] The state has since implemented or considered stricter regulations and harsher penalties for spills associated with resource extraction.[112]

New Mexico is a major producer of greenhouse gases.[113] A study by Colorado State University showed that the state's oil and gas industry generated 60 million metric tons of greenhouse gases in 2018, over four times greater than previously estimated.[113] The fossil fuels sector accounted for over half the state's overall emissions, which totaled 113.6 million metric tons, about 1.8% of the country's total and more than twice the national average per capita.[113][114] The New Mexico government has responded with efforts to regulate industrial emissions, promote renewable energy, and incentivize the use of electric vehicles.[114][115]

Settlements

editWith just 17 people per square mile (6.6 people/km2), New Mexico is one of the least densely populated states, ranking 45th out of 50; by contrast, the overall population density of the U.S. is 90 people per square mile (35 people/km2). The state is divided into 33 counties and 106 municipalities, which include cities, towns, villages, and a consolidated city-county, Los Alamos. Only three cities have at least 100,000 residents: Albuquerque, Rio Rancho, and Las Cruces, whose respective metropolitan areas together account for the majority of New Mexico's population.

Residents are concentrated in the north-central region of New Mexico, anchored by the state's largest city, Albuquerque. Centered in Bernalillo County, the Albuquerque metropolitan area includes New Mexico's third-largest city, Rio Rancho, and has a population of over 918,000, accounting for one-third of all New Mexicans. It is adjacent to Santa Fe, the capital and fourth-largest city. Altogether, the Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Los Alamos combined statistical area includes more than 1.17 million people, or nearly 60% of the state population.

New Mexico's other major center of population is in south-central area around Las Cruces, its second-largest city and the largest city in the southern region of the state. The Las Cruces metropolitan area includes roughly 214,000 residents, but with neighboring El Paso, Texas forms a combined statistical area numbering over 1 million.[116]

New Mexico hosts 23 federally recognized tribal reservations, including part of the Navajo Nation, the largest and most populous tribe; of these, 11 hold off-reservation trust lands elsewhere in the state. The vast majority of federally recognized tribes are concentrated in the northwest, followed by the north-central region.

Like several other southwestern states, New Mexico hosts numerous colonias, unincorporated, low-income slums characterized by abject poverty, the absence of basic services (such as water and sewage), and scarce housing and infrastructure.[117] The University of New Mexico estimates there are 118 colonias in the state, though the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development identifies roughly 150.[118] The majority are located along the Mexico-U.S. border.

Largest cities or towns in New Mexico

Source: 2017 U.S. Census Bureau estimate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

| Albuquerque Las Cruces |

1 | Albuquerque | Bernalillo | 558,545 | Rio Rancho Santa Fe | ||||

| 2 | Las Cruces | Doña Ana | 101,712 | ||||||

| 3 | Rio Rancho | Sandoval / Bernalillo | 96,159 | ||||||

| 4 | Santa Fe | Santa Fe | 83,776 | ||||||

| 5 | Roswell | Chaves | 47,775 | ||||||

| 6 | Farmington | San Juan | 45,450 | ||||||

| 7 | Clovis | Curry | 38,962 | ||||||

| 8 | Hobbs | Lea | 37,764 | ||||||

| 9 | Alamogordo | Otero | 31,248 | ||||||

| 10 | Carlsbad | Eddy | 28,774 | ||||||

Demographics

editPopulation

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 61,547 | — | |

| 1860 | 93,516 | 51.9% | |

| 1870 | 91,874 | −1.8% | |

| 1880 | 119,565 | 30.1% | |

| 1890 | 160,282 | 34.1% | |

| 1900 | 195,310 | 21.9% | |

| 1910 | 327,301 | 67.6% | |

| 1920 | 360,350 | 10.1% | |

| 1930 | 423,317 | 17.5% | |

| 1940 | 531,818 | 25.6% | |

| 1950 | 681,187 | 28.1% | |

| 1960 | 951,023 | 39.6% | |

| 1970 | 1,016,000 | 6.8% | |

| 1980 | 1,302,894 | 28.2% | |

| 1990 | 1,515,069 | 16.3% | |

| 2000 | 1,819,046 | 20.1% | |

| 2010 | 2,059,179 | 13.2% | |

| 2020 | 2,117,522 | 2.8% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[119] | |||

The 2020 census recorded a population of 2,117,522, an increase of 2.8% from 2,059,179 in the 2010 census.[120] This was the lowest rate of growth in the western U.S. after Wyoming, and among the slowest nationwide.[121] By comparison, between 2000 and 2010, New Mexico's population increased by 11.7% from 1,819,046—among the fastest growth rates in the country.[122] A report commissioned in 2021 by the New Mexico Legislature attributed the state's slow growth to a negative net migration rate, particularly among those 18 or younger, and to a 19% decline in the birth rate.[121] However, growth among Hispanics and Native Americans remained healthy.[123]

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated a slight decrease in population, with 3,333 fewer people from July 2021 to July 2022.[124] This was attributed to deaths exceeding births by roughly 5,000, with net migration mitigating the loss by 1,389.[124]

More than half of New Mexicans (51.4%) were born in the state; 37.9% were born in another state; 1.1% were born in either Puerto Rico, an island territory, or abroad to at least one American parent; and 9.4% were foreign born (compared to a national average of roughly 12%).[125] Almost a quarter of the population (22.7%) was under the age of 18, and the state's median age of 38.4 is slightly above the national average of 38.2. New Mexico's somewhat older population is partly reflective of its popularity among retirees: It ranked as the most popular retirement destination in 2018,[126] with an estimated 42% of new residents being retired.[127]

Hispanics and Latinos constitute nearly half of all residents (49.3%), giving New Mexico the highest proportion of Hispanic ancestry among the fifty states. This broad classification includes descendants of Spanish colonists who settled between the 16th and 18th centuries as well as recent immigrants from Latin America (particularly Mexico and Central America).

From 2000 to 2010, the number of persons in poverty increased to 400,779, or approximately one-fifth of the population.[122] The 2020 census recorded a slightly reduced poverty rate of 18.2%, albeit the third highest among U.S. states, compared to a national average of 10.5%. Poverty disproportionately affects minorities, with about one-third of African Americans and Native Americans living in poverty, compared with less than a fifth of whites and roughly a tenth of Asians; likewise, New Mexico ranks 49th among states for education equality by race and 32nd for its racial gap in income.[128]

New Mexico's population is among the most difficult to count, according to the Center for Urban Research at the City University of New York, due to the state's size, sparse population, and numerous isolated communities.[121] Likewise, the Census Bureau estimated that roughly 43% of the state's population (about 900,000 people) live in such "hard-to-count" areas.[121] In response, the New Mexico government invested heavily in public outreach to increase census participation, resulting in a final tally that exceeded earlier estimates and outperformed several neighboring states.[129]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 2,560 homeless people in New Mexico.[130][131]

Race and ethnicity

editNew Mexico is one of seven "majority-minority" states where non-Hispanic whites constitute less than half the population.[132] As early as 1940, roughly half the population was estimated to be nonwhite.[133] Before becoming a state in 1912, New Mexico was among the few U.S. territories that was predominately nonwhite, which contributed to its delayed admission into the Union.[134]

The largest ethnic group is Hispanic and Latino Americans; according to the 2020 census they account for nearly half the state's population, at 47.7%; they include Hispanos descended from pre-United States settlers and more recent successions of Mexican Americans.[135]

New Mexico has the fourth largest Native American community in the U.S., at over 200,000; comprising roughly one-tenth of all residents, this is the second largest population by percentage after Alaska.[136][137] New Mexico is also the only state besides Alaska where indigenous people have maintained a stable proportion of the population for over a century: In 1890, Native Americans made up 9.4% of New Mexico's population, almost the same percentage as in 2020.[138] By contrast, during that same period, neighboring Arizona went from one-third indigenous to less than 5%.[138]

New Mexico's population consists of many mestizo Indo-Hispano groups, including Hispanos of Oasisamerican descent and Indigenous Mexican American with Mesoamerican ancestry.[139][140]

Non-Hispanic White 40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%Native American40–50%80–90%Hispanic or Latino 40–50%50–60%60–70%70–80%

| Racial composition | 1970[141] | 1990[141] | 2000[142] | 2010[143] | 2020[144] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic or Latino | 37.4% | 38.2% | 42.1% | 46.3% | 47.7% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 53.8% | 50.4% | 44.7% | 40.5% | 36.5% |

| Native | 7.2% | 8.9% | 9.5% | 9.4% | 10.0% |

| Black | 1.9% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 2.1% | 2.1% |

| Asian | 0.2% | 0.9% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.8% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other | 0.6% | 12.6% | 17.0% | 15.0% | 15.0% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 3.6% | 3.7% | 19.9% |

According to the 2022 American Community Survey,[145][146][147] the most commonly claimed ancestry groups in New Mexico were:

- Mexican (32.8%)

- Other Hispanic (Hispano/Spanish) (15.3%)

- English (8.0%)

- German (7.9%)

- Irish (6.4%)

- Navajo (6.3%)

- Pueblo (2.4%)

Census data from 2020 found that 19.9% of the population identifies as multiracial/mixed-race, a population larger than the Native American, Black, Asian and NHPI population groups.[144] Almost 90% of the multiracial population in New Mexico identifies as Hispanic or Latino.[148]

Immigration

editA little over 9% of New Mexican residents are foreign-born, and an additional 6.0% of U.S.-born residents live with at least one immigrant parent.[149] The proportion of foreign-born residents is below the national average of 13.7%, and New Mexico was the only state to see a decline in its immigrant population between 2012 and 2022.[150]

In 2018, the top countries of origin for New Mexico's immigrants were Mexico, the Philippines, India, Germany and Cuba.[151] As of 2021, the vast majority of immigrants in the state came from Mexico (67.6%), followed by the Philippines (3.1%) and Germany (2.4%).[149]

Notwithstanding their relatively small population, immigrants play a disproportionately large role in New Mexico's economy, accounting for almost one-eighth (12.5%) of the labor force,15% of entrepreneurs, and 19.1% of personal care aides, as well as 9.1% of workers in STEM fields.[149]

Languages

edit| English only | 64% |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 28% |

| Navajo | 4% |

| Others | 4% |

New Mexico ranks third after California and Texas in the number of multilingual residents.[152] According to the 2010 U.S. census, 28.5% of the population age 5 and older speak Spanish at home, while 3.5% speak Navajo.[153] Some speakers of New Mexican Spanish are descendants of pre-18th century Spanish settlers.[154] Contrary to popular belief, New Mexican Spanish is not an archaic form of 17th-century Castilian Spanish; though some archaic elements exist, linguistic research has determined that the dialect "is neither more Iberian nor more archaic" than other varieties spoken in the Americas.[155][156] Nevertheless, centuries of isolation during the colonial period insulated the New Mexican dialect from "standard" Spanish, leading to the preservation of older vocabulary as well as its own innovations.[157][158]

Besides Navajo, which is also spoken in Arizona, several other Native American languages are spoken by smaller groups in New Mexico, most of which are endemic to the state. Native New Mexican languages include Mescalero Apache, Jicarilla Apache, Tewa, Southern Tiwa, Northern Tiwa, Towa, Keres (Eastern and Western), and Zuni. Mescalero and Jicarilla Apache are closely related Southern Athabaskan languages, and both are also related to Navajo. Tewa, the Tiwa languages, and Towa belong to the Kiowa-Tanoan language family, and thus all descend from a common ancestor. Keres and Zuni are language isolates with no relatives outside of New Mexico.

Official language

editNew Mexico's original state constitution of 1911 required all laws be published in both English and Spanish for twenty years after ratification;[159] this requirement was renewed in 1931 and 1943,[160] with some sources stating the state was officially bilingual until 1953.[161] Nonetheless, the current constitution does not declare any language "official".[162] While Spanish was permitted in the legislature until 1935, all state officials are required to have a good knowledge of English; consequently, some analysts argue that New Mexico cannot be considered a bilingual state, since not all laws are published in both languages.[160]

However, the state legislature remains constitutionally empowered to publish laws in English and Spanish and to appropriate funds for translation. Whenever a referendum to approve an amendment to the New Mexican constitution is held, the ballots must be printed in both English and Spanish.[163] Certain legal notices must be published in both English and Spanish as well, and the state maintains a list of newspapers for Spanish publication.[164]

With regard to the judiciary, witnesses and defendants have the right to testify in either of the two languages, and monolingual speakers of Spanish have the same right to be considered for jury duty as do speakers of English.[162][165] In public education, the state has the constitutional obligation to provide bilingual education and Spanish-speaking instructors in school districts where the majority of students are Hispanophone.[162] The constitution also provides that all state citizens who speak neither English nor Spanish have a right to vote, hold public office, and serve on juries.[166]

In 1989, New Mexico became the first of only four states to officially adopt the English Plus resolution, which supports acceptance of non-English languages.[167] In 1995, the state adopted an official bilingual song, "New Mexico – Mi Lindo Nuevo México".[168]: 75, 81 In 2008, New Mexico was the first state to officially adopt a Navajo textbook for use in public schools.[169]

Religion

editReligious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[170]

Like most U.S. states, New Mexico is predominantly Christian, with Roman Catholicism and Protestantism each constituting roughly a third of the population. According to Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA), the largest denominations in 2010 were the Catholic Church (684,941 members); the Southern Baptist Convention (113,452); The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (67,637), and the United Methodist Church (36,424).[171] Approximately one-fifth of residents are unaffiliated with any religion, which includes atheists, agnostics, deists. A 2020 study by the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) determined 67% of the population were Christian, with Roman Catholics constituting the largest denominational group.[172] In 2022, the PRRI estimated 63% of the population were Christian.[173]

Roman Catholicism is deeply rooted in New Mexico's history and culture, going back to its settlement by the Spanish in the early 17th century. The oldest Christian church in the continental U.S., and the third oldest in any U.S. state or territory, is the San Miguel Mission in Santa Fe, which was built in 1610. Within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, New Mexico belongs to the ecclesiastical province of Santa Fe. The state has three ecclesiastical districts:[174] the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, the Diocese of Gallup, and the Diocese of Las Cruces.[175] Evangelicalism and nondenominational Christianity have seen growth in the state since the late 20th century: The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association has hosted numerous events in New Mexico,[176][177] and Albuquerque has several megachurches, which have numerous satellite locations in the state, including Calvary of Albuquerque, Legacy Church, and Sagebrush Church.[178]

New Mexico has been a leading center of the New Age movement since at least the 1960s, attracting adherents from across the country.[179] The state's "thriving New Age network" encompasses various schools of alternative medicine, Holistic Health, psychic healing, and new religions, as well as festivals, pilgrimage sites, spiritual retreats, and communes.[180][181] New Mexico's Japanese American community has influenced the state's religious heritage, with Shinto and Zen represented by Kagyu Shenpen Kunchab, Kōbun Chino Otogawa, Upaya Institute and Zen Center.[182] Likewise, Holism is represented in New Mexico, as are associated faiths such as Buddhism and Seventh-day Adventism;[183][184] a Tibetan Buddhist temple is located at Zuni Mountain Stupa in Grants.

Religious education, art, broadcasting, media exist across religions and faiths in New Mexico, including KHAC, KXXQ, Dar al-Islam, and Intermountain Jewish News. Christian schools in New Mexico are encouraged to receive educational accreditation, and among them are the University of the Southwest, St. Pius High School, Hope Christian, Sandia View Academy, St. Michael's High School, Las Cruces Catholic School, St. Bonaventure Indian School, and Rehoboth Christian School. Albuquerque's growing media sector has made it a popular hub for several national Christian media institutions, such as Trinity Broadcasting Network's KNAT-TV. Christian artistic expression includes the gospel tradition within New Mexico music,[185] and contemporary Christian music such as KLYT radio station.[186] Several indigenous and Christian religious sites are registered and protected as part of regional and global cultural heritage.[187][188]

Reflecting centuries of successive migrations and settlements, New Mexico has developed a distinct syncretic folk religion that is centered on Puebloan traditions and Hispano folk Catholicism, with some elements of Diné Bahaneʼ, Apache, Protestant, and Evangelical faiths.[189] This unique religious tradition is sometimes referred to as "Pueblo Christianity" or "Placita Christianity", referring to both the Pueblos and Hispanic town squares.[190] Customs and practices include the maintenance of acequias,[191] Pueblo and Territorial Style churches,[191] ceremonial dances such as the matachines,[192][193] religious artistic expression of kachinas and santos,[194] religious holidays celebrating saints such as Pueblo Feast Days,[195] Christmas traditions of bizcochitos and farolitos or luminarias,[196][197] and pilgrimages like that of El Santuario de Chimayo.[198] The luminaria tradition is a cultural hallmark of the Pueblos and Hispanos of New Mexico and a part of the state's distinct heritage. The luminaria custom has spread nationwide, both as a Christmas tradition as well as for other events. New Mexico's distinctive faith tradition is believed to reflect the religious naturalism of the state's indigenous and Hispano peoples, who constitute a pseudo ethnoreligious group.[199]

New Mexico's leadership within otherwise disparate traditions such as Christianity, the Native American Church, and New Age movements has been linked to its remote and ancient indigenous spirituality, which emphasized sacred connections to nature, and its over 300 years of syncretized Pueblo and Hispano religious and folk customs.[179][180] The state's remoteness has likewise been cited as attracting and fostering communities seeking the freedom to practice or cultivate new beliefs.[180] Global spiritual leaders including Billy Graham and Dalai Lama, along with community leaders of Hispanic and Latino Americans and indigenous peoples of the North American Southwest, have remarked on New Mexico being a sacred space.[200][201][202]

According to a 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center, New Mexico ranks 18th among the 50 U.S. states in religiosity, 63% of respondents stating they believe in God with certainty, with an additional 20% being fairly certain of the existence of God, while 59% considering religion to be important in their lives and another 20% believe it to be somewhat important.[203] Among its population in 2022, 31% were unaffiliated.[173]

Economy

editThis section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (June 2024) |

Oil and gas production, the entertainment industry, high tech scientific research, tourism, and government spending are important drivers of the state economy.[204] The state government has an elaborate system of tax credits and technical assistance to promote job growth and business investment, especially in new technologies.[205]

As of 2021, New Mexico's gross domestic product was over $95 billion,[206] compared to roughly $80 billion in 2010.[207] State GDP peaked in 2019 at nearly $99 billion but declined in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, the per capita personal income was slightly over $45,800, compared to $31,474 in 2007;[208] it was the third lowest in the country after West Virginia and Mississippi.[209] The percentage of persons below the poverty level has largely plateaued in the 21st century, from 18.4% in 2005 to 18.2% in 2021.[210][211]

Traditionally dependent on resource extraction, ranching, and railroad transportation, New Mexico has increasingly shifted towards services, high-end manufacturing, and tourism.[212][213] Since 2017, the state has seen a steady rise in the number of annual visitors, culminating in a record-breaking 39.2 million tourists in 2021, which had a total economic income of $10 billion.[214] New Mexico has also seen greater investment in media and scientific research.

Oil and gas

editNew Mexico is the second largest crude oil and ninth largest natural gas producer in the United States;[215] it overtook North Dakota in oil production in July 2021 and is expected to continue expanding.[216] The Permian and San Juan Basins, which are located partly in New Mexico, account for some of these natural resources. In 2000 the value of oil and gas produced was $8.2 billion,[217] and in 2006, New Mexico accounted for 3.4% of the crude oil, 8.5% of the dry natural gas, and 10.2% of the natural gas liquids produced in the United States.[218] However, the boom in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling since the mid-2010s led to a large increase in the production of crude oil from the Permian Basin and other U.S. sources; these developments allowed the United States to again become the world's largest producer of crude oil by 2018.[219][220][221][222] New Mexico's oil and gas operations contribute to the state's above-average release of the greenhouse gas methane, including from a national methane hot spot in the Four Corners area.[223][224][225][226]

In common with other states in the Western U.S., New Mexico receives royalties from the sale of federally owned land to oil and gas companies.[227] It has the highest proportion of federal land with oil and gas, as well as the most lucrative: since the last amendment to the U.S. Mineral Leasing Act in 1987, New Mexico had by far the lowest percent of land sold for the minimum statutory amount of $2 per acre, at just 3%; by contrast, all of Arizona's federal land was sold at the lowest rate, followed by Oregon at 98% and Nevada at 84%.[227] The state had the fourth-highest total acreage sold to the oil and gas industry, at about 1.1 million acres, and the second-highest number of acres currently leased fossil fuel production, at 4.3 million acres, after Wyoming's 9.2 million acres; only 11 percent of these lands, or 474,121 acres, are idle, which is the lowest among Western states.[227] Nevertheless, New Mexico has had recurring disputes and discussions with the U.S. government concerning management and revenue rights over federal land.[228]

Arts and entertainment

editReflecting the artistic traditions of the American Southwest, New Mexican art has its origins in the folk arts of the indigenous and Hispanic peoples in the region. Pueblo pottery, Navajo rugs, and Hispano religious icons like kachinas and santos are recognized in the global art world.[229] Georgia O'Keeffe's presence brought international attention to the Santa Fe art scene, and today the city has several notable art establishments and many commercial art galleries along Canyon Road.[230] As the birthplace of William Hanna, and the residence of Chuck Jones, the state also connections to the animation industry.[231][232]

New Mexico provides financial incentives for film production, including tax credits valued at 25–40% of eligible in-state spending.[233][234] A program enacted in 2019 provides benefits to media companies that commit to investing in the state for at least a decade and that use local talent, crew, and businesses.[235] According to the New Mexico Film Office, in 2022, film and television expenditures reached the highest recorded level at over $855 million, compared to $624 million the previous year.[236] During fiscal years 2020–2023, the total direct economic impact from the film tax credit was $2.36 million. In 2018, Netflix chose New Mexico for its first U.S. production hub, pledging to spend over $1 billion over the next decade to create one of the largest film studios in North America at Albuquerque Studios.[237] NBCUniversal followed suit in 2021 with the opening of its own television film studio in the city, committing to spend $500 million in direct production and employ 330 full-time equivalent local jobs over the next decade.[235] Albuquerque is consistently recognized by MovieMaker magazine as one of the top "big cities" in North America to live and work as a filmmaker, and the only city to earn No. 1 for four consecutive years (2019–2022); in 2024, it placed second, after Toronto.[238]

Country music record labels have a presence in the state, following the former success of Warner Western.[239][240][241][242][243] During the 1950s to 1960s, Glen Campbell, The Champs, Johnny Duncan, Carolyn Hester, Al Hurricane, Waylon Jennings, Eddie Reeves, and JD Souther recorded on equipment by Norman Petty at Clovis. Norman Petty's recording studio was a part of the rock and roll and rockabilly movement of the 1950s, with the distinctive "Route 66 Rockabilly" stylings of Buddy Holly and The Fireballs.[244] Albuquerque has been referred to as the "Chicano Nashville" due to the popularity of regional Mexican and Western music artists from the region.[245] A heritage style of country music, called New Mexico music, is widely popular throughout the southwestern U.S.; outlets for these artists include the radio station KANW, Los 15 Grandes de Nuevo México music awards, and Al Hurricane Jr. hosts Hurricane Fest to honor his father's music legacy.[246][247][248]

Technology

editNew Mexico is part of the larger Rio Grande Technology Corridor, an emerging alternative to Silicon Valley[249] consisting of clusters of science and technology institutions stretching from southwestern Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico.[250] The constituent New Mexico Technology Corridor, centered primarily around Albuquerque, hosts a constellation of high technology and scientific research entities, which include federal facilities such as Sandia National Laboratories, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the Very Large Array; private companies such as Intel, HP, and Facebook; and academic institutions such as the University of New Mexico (UNM), New Mexico State University (NMSU), and New Mexico Tech.[251][252][76][253][254] Most of these entities form part of an "ecosystem" that links their researchers and resources with private capital, often through initiatives of local, state, and federal governments.[255]

New Mexico has been a science and technology hub since at least the mid-20th century, following heavy federal government investment during the Second World War. Los Alamos was the site of Project Y, the laboratory responsible for designing and developing the world's first atomic bomb for the Manhattan Project. Horticulturist Fabián García developed several new varieties of peppers and other crops at what is now NMSU, which is also a leading space grant college. Robert H. Goddard, credited with ushering the space age, conducted many of his early rocketry tests in Roswell. Astronomer Clyde Tombaugh of Las Cruces discovered Pluto in neighboring Arizona. Personal computer company MITS, which was founded in Albuquerque in 1969, brought about the "microcomputer revolution" with the development of the first commercially successful microcomputer, the Altair 8800; two of its employees, Paul Allen and Bill Gates, later founded Microsoft in the city in 1975.[256][257][258] Multinational technology company Intel, which has had operations in Rio Rancho since 1980, opened its Fab 9 factory in the city in January 2024, part of its commitment to invest $3.5 billion in expanding its operations in the state; it is the company's first high-volume semiconductor operation and the only U.S. factory producing the world's most advanced packaging solutions at scale.[259]

The New Mexican government has aimed to develop the state into a major center for technology startups, namely through financial incentives and public-private partnerships.[255] The bioscience sector has experienced particularly robust growth, beginning with the 2013 opening of a BioScience Center in Albuquerque, the state's first private incubator for biotechnology startups; New Mexicans have since founded roughly 150 bioscience companies, which have received more patents than any other sector.[205] In 2017, New Mexico established the Bioscience Authority to foster local industry development; the following year, pharmaceutical company Curia built two large facilities in Albuquerque, and in 2022 announced plans to invest $100 million to expand local operations.[205] The state is also positioning itself to play a leading role in developing quantum computing, quantum dot, and clean energy technologies.[260][261]

New Mexico's high altitude, generally clear skies, and sparse population have long fostered astronomical and aerospace activities, beginning with the ancient observatories of the Chaco Canyon culture; the "Space Triangle" between Roswell, Alamogordo, and Las Cruces has seen the highest concentration rocket tests and launches.[262] New Mexico is sometimes considered the birthplace of the U.S. space program, beginning with Goddard's design of the first liquid fuel rocket in Roswell in the 1930s.[263] The first rocket to reach space flew from White Sands Missile Range in 1948, and both NASA and the Department of Defense continue to develop and test rockets there and at the adjacent Holloman Air Force Base.[262] New Mexico has also become a major center for private space flight, hosting the world's first purpose-built commercial spaceport, Spaceport America, which anchors several major aerospace companies and associated contractors, most notably Branson's Virgin Galactic.[264]

In November 2022, the New Mexico State Investment Council, which manages that state's $38 billion sovereign wealth fund, announced it would commit $100 million towards America's Frontier Fund (AFF), a new venture capital firm that will focus on advanced technologies such as microelectronics and semiconductors, advanced manufacturing, artificial intelligence, new energy sources, synthetic biology and quantum sciences.[265]

Agriculture and food production

editAlthough much of its land is arid, New Mexico has hosted a variety of agricultural activities for at least 2,500 years, centered mostly on the Rio Grande and its tributaries. This is helped by its long history of acequias, along with other farming and ranching methods within New Mexico. It is regulated by the New Mexico Department of Agriculture, specialty areas include various cash crops, cattle ranching, farming, game and fish.

Agriculture contributes $40 billion to New Mexico's economy and employs nearly 260,000 people. As of 2023, the state exports $275 million in agricultural goods and ranks first nationwide in the production of chile peppers, second in pecans, and fifth in onions.[266]

The state vegetables are New Mexico chile peppers and pinto beans, with the former being the most famous and valuable crop. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, New Mexico ranked first in the nation for chile pepper acreage, with Doña Ana and Luna counties placing first and second among U.S. counties in this regard.[267] New Mexico chile sold close to $40 million in 2021, while dry beans accounted for $7.6 million that year. New Mexico is one of the few states commercially producing pistachios, and its piñon harvest (pine nut) is a protected commodity.[268][269][270][271]

Dairy is the state's largest commodity, with sales of milk alone totaling $1.3 billion.[267] Dean Foods owns the Creamland brand in New Mexico, the brand was originally founded in 1937 to expand a cooperative dairy venture known as the Albuquerque Dairy Association.[272] Southwest Cheese Company in Clovis is the among largest cheese production facilities in the United States.[273][274]

Caballero history among the indigenous and Hispano communities in New Mexico have resulted in large-scale ranch lands throughout the state, most of which are within historically Apache, Navajo, Pueblo, and Spanish land grants.[275] Wild game and fish found in the state include Rio Grande cutthroat trout, rainbow trout, crawdads, and venison.

Restaurant chains originating in the state include Blake's Lotaburger, Boba Tea Company, Dion's Pizza, Little Anita's, Mac's Steak in the Rough, and Twisters; many specialize in New Mexican cuisine. Some companies like Allsup's gas stations have consumer foods, like chimichangas.[276]

Tourism

editNew Mexico's distinctive culture, rich artistic scene, favorable climate, and diverse geography have long been major drivers of tourism. As early as 1880, the state was a major destination for travelers suffering from respiratory illnesses (particularly tuberculosis), with its altitude and aridity believed to be beneficial to the lungs.[277] Since the mid aughts, New Mexico has seen a steady rise in annual visitors, welcoming a record-breaking 39.2 million tourists in 2021.[214]

New Mexico's unique culinary scene has garnered increasing national attention, including numerous James Beard Foundation Awards.[278] The state has been featured in major travel television shows such as Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives, Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown, Man v. Food Nation, and others. Outdoor recreation in the area is fueled by a variety of internationally recognized nature reserves, public parks, ski resorts, hiking trails, and hunting and fishing areas.

New Mexico's government is actively involved in promoting tourism, launching the nation's first state publication, New Mexico Magazine, in 1923.[279] The New Mexico Tourism Department administers the magazine and is also responsible for the New Mexico True campaign.

Government

editFederal government spending is a major driver of the New Mexico economy. In 2021, the federal government spent $2.48 on New Mexico for every dollar of tax revenue collected from the state, higher than every state except Kentucky.[280] The same year, New Mexico received $9,624 per resident in federal services, or roughly $20 billion more than what the state pays in federal taxes.[281] The state governor's office estimated that the federal government spends roughly $7.8 billion annually in services such as healthcare, infrastructure development, and public welfare.[121]

Federal employees make up 3.4% of New Mexico's labor force.[227] Many federal jobs in the state relate to the military: the state hosts three air force bases (Kirtland Air Force Base, Holloman Air Force Base, and Cannon Air Force Base); a testing range (White Sands Missile Range); and an army proving ground (Fort Bliss's McGregor Range). A 2005 study by New Mexico State University estimated that 11.7% of the state's total employment arises directly or indirectly from military spending.[282] New Mexico is also home to two major federal research institutions: the Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratories. The former alone accounts for 24,000 direct and indirect jobs and over $3 billion in annual federal investment as of 2019.[283]