Curaçao,[a] officially the Country of Curaçao (Dutch: Land Curaçao;[10] Papiamentu: Pais Kòrsou),[11][12] is a Lesser Antilles island in the southern Caribbean Sea, specifically the Dutch Caribbean region, about 65 km (40 mi) north of Venezuela. It is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[13]

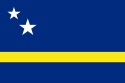

Curaçao Kòrsou (Papiamento) | |

|---|---|

| Country of Curaçao Land Curaçao (Dutch) Pais Kòrsou (Papiamento) | |

| Anthem: "Himno di Kòrsou" (English: "Anthem of Curaçao") | |

| Royal anthem: "Wilhelmus" (English: "William of Nassau") | |

Location of Curaçao (circled in red) | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Country status | 10 October 2010 |

| Capital and largest city | Willemstad 12°7′N 68°56′W / 12.117°N 68.933°W |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2018) | 75.4% Curaçaoans 9% Dutch 3.6% Dominican 3% Colombian 1.2% Haitian 1.2% Surinamese 1.1% Venezuelan 1.1% Aruban 0.9% unspecified 6% other[1] |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Curaçaoan |

| Government | Parliamentary representative democracy within a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Willem-Alexander |

• Governor | Lucille George-Wout |

• Speaker | Charetti America-Francisca |

| Gilmar Pisas | |

| Legislature | Parliament of Curaçao |

| Area | |

• Total | 444[2] km2 (171 sq mi) (181th) |

| Highest elevation | 372 m (1,220 ft) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 148,925[3] (177th) |

• Density | 349.13/km2 (904.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2021[4] estimate |

• Total | $5.5 billion (184th) |

• Per capita | $35,484 (45th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2021 estimate |

• Total | $3.5 billion[5] (149th) |

• Per capita | $22,581 (40th) |

| HDI (2012) | 0.811[6] very high |

| Currency | Netherlands Antillean guilder (ƒ) |

| Time zone | UTC-4:00 (AST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +5999 |

| ISO 3166 code | |

| Internet TLD | .cw |

Curaçao includes the main island of Curaçao and the much smaller, uninhabited island of Klein Curaçao ("Little Curaçao").[12] Curaçao has a population of 158,665 (January 2019 est.),[2] with an area of 444 km2 (171 sq mi); its capital is Willemstad.[12] Together with Aruba and Bonaire, Curaçao forms the ABC islands. Collectively, Curaçao, Aruba, and other Dutch islands in the Caribbean are often called the Dutch Caribbean. It is the largest of the ABC islands in area and population, as well as the largest in the Dutch Caribbean.[14]

The name "Curaçao" may originate from the indigenous autonym of its people; this idea is supported by early Spanish accounts referring to the inhabitants as Indios Curaçaos. Curaçao's history begins with the Arawak and Caquetio Amerindians; the island becoming a Spanish colony after Alonso de Ojeda's 1499 expedition. Though labelled "the useless island" due to its poor agricultural yield and lack of precious metals, it became a strategic cattle ranching area. When the Dutch colonized the island in 1634, they shifted the island's focus to trade and shipping, and later made it a hub of the Atlantic slave trade. Members of the Jewish community, fleeing persecution in Europe, settled here and significantly influenced the economy and culture.

British forces occupied Curaçao twice during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars but it was returned to Dutch rule. The abolition of slavery in 1863 led to economic shifts and migrations. Dutch remains the official language, though Papiamentu, English, and Spanish are widely spoken, reflecting the island's diverse cultural influences. Curaçao was formerly part of the Curaçao and Dependencies colony from 1815 to 1954 and later the Netherlands Antilles from 1954 to 2010, as Island Territory of Curaçao.[15][16][12]

The discovery of oil in the Maracaibo Basin in 1914 transformed Curaçao into a critical refinery location, altering its economic landscape. There were efforts towards becoming a country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands; the island achieved autonomy in 2010.

Etymology

editOne explanation for the island's name is that Curaçao was the autonym by which its indigenous peoples identified themselves.[17] Early Spanish accounts support this theory, referring to the indigenous peoples as Indios Curaçaos.[18]

From 1525, the island was featured on Spanish maps as Curaçote, Curasaote, Curasaore, and even Curacaute.[19] By the 17th century, it appeared on most maps as Curaçao or Curazao.[18] On a map created by Hieronymus Cock in 1562 in Antwerp, the island was called Qúracao.[20]

A persistent but undocumented story claims the following: in the 16th and 17th centuries—the early years of European exploration—when sailors on long voyages got scurvy from lack of vitamin C, sick Portuguese or Spanish sailors were left on the island now known as Curaçao. When their ship returned, some had recovered, probably after eating vitamin C-rich fruit there. From then on, the Portuguese allegedly referred to the island as Ilha da Curação (Island of Healing) or the Spanish as Isla de la Curación.[12]

History

editPre-colonial

editThe original inhabitants of Curaçao were the Arawak and Caquetio Amerindians.[21] Their ancestors had migrated to the island from the mainland of South America, probably hundreds of years before Europeans' first arrival.

Spanish colonization

editThe first Europeans recorded as seeing the island were members of a Spanish expedition under the leadership of Alonso de Ojeda in 1499.[21] The Spaniards enslaved most of the Caquetios (Arawak) for forced labour in their Hispaniola colony, but paid little attention to the island itself.[21] In 1515, almost all of the 2,000 Caquetios living there were also transported to Hispaniola as slaves.

Established in 1499 as a Spanish launchpad for exploring northern South America, Curaçao was officially settled by Spain in 1527. It functioned as an island extension of Venezuela throughout the 1500s. As mainland colonization advanced, Spain slowly withdrew from the island. The city registry of Caracas, Venezuela holds one of the earliest written mentions of Curaçao. A document dated 9 December 1595 states that Francisco Montesinos, priest and vicar of "the Yslas de Curasao, Aruba and Bonaire" conferred his power of attorney to Pedro Gutiérrez de Lugo, a Caracas resident, to collect his ecclesiastic salary from the Royal Treasury of King Philip II of Spain.

The Spanish introduced numerous tree, plant and animal species to Curaçao, including horses, sheep, goats, pigs and cattle from Europe and other Spanish colonies. In general, imported sheep, goats and cattle did relatively well. Cattle were herded by Caquetios and Spaniards and roamed freely in the kunuku plantations and savannas.

Not all imported species fared equally well, and the Spanish also learned to use Caquetio crops and agricultural methods, as well as those from other Caribbean islands. Though historical sources point to thousands of people living on the island, agricultural yields were disappointing; this and the lack of precious metals in the salt mines led the Spanish to call Curaçao "the useless island".

Over time, the number of Spaniards living on Curaçao decreased while the number of aboriginal inhabitants stabilized. Presumably through natural growth, return and colonization, the Caquetio population then began to increase. In the last decades of Spanish occupation, Curaçao was used as a large cattle ranch. At that point, Spaniards lived around Santa Barbara, Santa Ana and in the villages in the western part of the island, while the Caquetios are thought to have lived scattered all over the island.

Dutch colonial rule

editIn 1634, during the Eighty Years' War of independence between the Republic of the Netherlands and Spain, the Dutch West India Company under Admiral Johann van Walbeeck invaded the island; the Spanish surrendered in San Juan in August. Approximately 30 Spaniards and many indigenous people were then deported to Santa Ana de Coro in Venezuela. About 30 Taíno families were allowed to live on the island while Dutch colonists started settling there.[21]

The Dutch West India Company founded the capital of Willemstad on the banks of an inlet called the Schottegat; the natural harbour proved an ideal place for trade. Commerce and shipping—and piracy—became Curaçao's most important economic activities. Later, salt mining became a major industry, the mineral being a lucrative export at the time.[citation needed] From 1662, the Dutch West India Company made Curaçao a centre of the Atlantic slave trade, often bringing slaves from West Africa to the island, before selling them elsewhere in the Caribbean and Spanish Main.[21]

Sephardic Jews fleeing persecution in Spain and Portugal sought safe haven in Dutch Brazil and the Dutch Republic. Many settled in Curaçao, where they made significant contributions to its civil society, cultural development and economic prosperity.[22] In 1674 the island became a free port.[23]

In the Franco-Dutch War of 1672–78, French Count Jean II d'Estrées planned to attack Curaçao. His fleet—12 men-of-war, three fire ships, two transports, a hospital ship, and 12 privateers—met with disaster, losing seven men-of-war and two other ships when they struck reefs off the Las Aves archipelago. The serious navigational error occurred on 11 May 1678, a week after the fleet set sail from Saint Kitts. To commemorate its narrow escape from invasion, Curaçao marked the events with a day of thanksgiving, which was celebrated for decades into the 18th century.[citation needed]

Many Dutch colonists grew affluent from the slave trade, building impressive colonial buildings in the capital of Willemstad; the city is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 1795, a major slave revolt took place under the leaders Tula Rigaud, Louis Mercier, Bastian Karpata, and Pedro Wakao. Up to 4,000 slaves in northwest Curaçao revolted, with more than 1,000 taking part in extended gunfights. After a month, the slave owners were able to suppress the revolt.[24][25]

Curaçao's proximity to South America resulted in interaction with cultures of the coastal areas more than a century after the independence of the Netherlands from Spain. Architectural similarities can be seen between 19th century Willemstad neighborhoods and the nearby Venezuelan city of Coro in Falcón State, which has also been designated a World Heritage Site. Netherlands established economic ties with the Viceroyalty of New Granada that included the present-day countries of Colombia and Venezuela. In the 19th century, Curaçaoans such as Manuel Piar and Luis Brión were prominently engaged in the wars of independence of both Venezuela and Colombia. Political refugees from the mainland, such as Simon Bolivar, regrouped in Curaçao.[26]

During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, British forces twice occupied Curaçao; the first occupation lasted from 1800 to 1803, and the second occupation from 1807 to 1815.[27] Stable Dutch rule returned in 1815 at the end of the Napoleonic wars, when the island was incorporated into the colony of Curaçao and Dependencies.[28]

The Dutch abolished slavery in 1863, causing vast changes in the economy with the shift to wage labour.[28] Some Curaçao inhabitants emigrated to other islands, such as Cuba, to work in sugarcane plantations. Other former slaves had nowhere to go and continued working for plantation owners under the tenant farmer system,[29] in which former slaves leased land from former masters, paying most of their harvest to owners as rent. The system lasted until the early 20th century.[citation needed]

Historically, Dutch was not widely spoken on the island outside of the colonial administration, but its use increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[30] Students on Curaçao, Aruba, and Bonaire were taught predominantly in Spanish until the early 19th century, when the British occupied all three islands. Teaching of Spanish was restored when Dutch rule resumed in 1815. Also, efforts were made to introduce widespread bilingual Dutch and Papiamentu education in the late 19th century.[31]

20th and 21st centuries

editWhen oil was discovered in the Venezuelan Maracaibo Basin town of Mene Grande in 1914, Curaçao's economy was dramatically altered. In the early years, both Shell and Exxon held drilling concessions in Venezuela, which ensured a constant supply of crude oil to refineries in Aruba and Curaçao. Crude oil production in Venezuela was inexpensive. Both Shell and Exxon were vertically integrated and controlled the entire industry, from pumping, transporting, and refining to sales. The refineries on Aruba and Curaçao operated in global markets and were profitable partly because of the margin between the production costs of crude oil and the revenues the sale of oil products. This provided a safety net for losses incurred through inefficiency or excessive operating costs at the refineries.[21][unreliable source?]

In 1929, Curaçao was attacked by Venezuelan rebel commander Rafael Simón Urbina, who, with 250 soldiers, captured the fort. The Venezuelans plundered weapons, ammunition, and the island's treasury. They also managed to capture the Governor of the island, Leonardus Albertus Fruytier (1882–1972), and hauled him off to Venezuela on a stolen American ship, Maracaibo. Fruytier was criticized and had to resign as governor. After returning to the Netherlands, he settled for a position as chief inspector in Maastricht. The Dutch increased their military presence on the island.[32][33]

In 1936 burning bale of cotton thrown overboard by the crew of the M. S. Colombia, which lay anchored in the Schottegat, caused the oil floating on the water to catch fire. It took days to get the fire under control; houses had to be evacuated, but there were no casualties.

During the Second World War, the island played an important role in the supply of fuel for the Allied forces. In 1940, before the invasion of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany, the British occupied Curaçao and the French Aruba. The presence of powers other than the Netherlands alarmed the Venezuelan government given the proximity of these islands at the entrance to the Gulf of Venezuela and the fact they'd historically been used as bases to launch incursions against Venezuelan territory. In 1941, US troops occupied the island and built military airport "Hato". The main purpose was this deployment was to fight against expected future attacks by Axis submarines and potentially long-distance Nazi bombers. America was also concerned over the potential threat of a German invasion of the continental US launched with the aid of German settlers in South America.

In 1942 the port of Willemstad, one of the main sources of fuel for the Allied operations, was besieged by German submarines on several occasions under Neuland Operation. In August 1942, the Germans returned to Curaçao and attacked a tanker and received fire from a Dutch shore battery before slipping away. The US Navy established the Fourth Fleet, which was responsible for countering enemy naval operations in the Caribbean and in the South Atlantic. The US Army also sent aircraft and personnel to help protect the oil refineries and bolster the Venezuelan Air Force.

In 1954, Curaçao and other Dutch Caribbean colonies were joined to form the Netherlands Antilles. Discontent with Curaçao's seemingly subordinate relationship to the Netherlands, ongoing racial discrimination, and a rise in unemployment owing to layoffs in the oil industry led to a series of riots in 1969.[34] The riots resulted in two deaths, numerous injuries and severe damage in Willemstad. In response, the Dutch government introduced far-reaching reforms, allowing Afro-Curaçaoans greater influence over the island's political and economic life, and increased the prominence of the local Papiamentu language.[35]

Curaçao experienced an economic downturn in the early 1980s. Shell's refinery on the island operated with significant losses from 1975 to 1979, and again from 1982 to 1985. Persistent losses, global overproduction, stronger competition, and low market expectations threatened the refinery's future. In 1985, after 70 years, Royal Dutch Shell decided to end its activities on Curaçao. This came at a crucial moment. Curaçao's fragile economy had been stagnant for some time. Several revenue-generating sectors suffered even more during this period: tourism from Venezuela collapsed after the devaluation of the bolivar, and a slowdown in the transportation sector had deleterious effects on the Antillean Airline Company and the Curaçao Dry Dock Company. The offshore financial services industry also experienced a downturn due to new U.S. tax laws.[citation needed]

In the mid-1980s, Shell sold its refinery for the symbolic amount of one Antillean guilder to a local government consortium. In recent years, the aging refinery has been the subject of lawsuits alleging that its emissions, including sulfur dioxide and particulate matter, far exceed safety standards.[36] The government consortium leases the refinery to the Venezuelan PDVSA state oil company.[36]

Continuing economic hardship in the late 1990s and early 2000s resulted in much emigration to the Netherlands.[37]

On 1 July 2007, Curaçao was due to become a country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, like Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles. On 28 November 2006, the change was delayed when the island council rejected a clarification memorandum on the process. A new island council ratified this agreement on 9 July 2007.[38] On 15 December 2008, Curaçao was again scheduled to become a separate country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands. A non-binding referendum on the move was held in Curaçao on 15 May 2009; 52% of voters supported it.[39]

Since the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles

editThe dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles came into effect on 10 October 2010.[40][41] Curaçao became a country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the kingdom retaining responsibility for defence and foreign policy. The kingdom was also tasked with overseeing the island's finances under a debt-relief arrangement agreed upon between the two.[42] Curaçao's first prime minister was Gerrit Schotte. He was succeeded in 2012 by Stanley Betrian, ad interim. After the 2012 elections, Daniel Hodge became the third prime minister on 31 December 2012.[43] He led a demissionary cabinet until 7 June 2013, when a new cabinet under the leadership of Ivar Asjes was sworn in.[44]

Although Curaçao is autonomous, the Netherlands has intervened in its affairs to ensure that parliamentary elections are held and to assist in finalizing accurate budgets. In July 2017, Curaçaoan Prime Minister Eugene Rhuggenaath said he wanted Curaçao to take full responsibility over its affairs, but asked for more cooperation and assistance from the Netherlands, with suggestions for more innovative approaches to help Curaçao succeed and increase its standard of living.[45][46] The Dutch government reminded the Curaçaoan government that it had provided assistance with oil refinery negotiations with the Chinese "on numerous occasions".[47]

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic resulted in austerity measures. Curaçao had to impose spending cuts to qualify for additional aid from the Netherlands.[48] As part of the austerity package, the Government of Curaçao announced a 12.5% cut in benefits for civil servants.[49] On 24 June 2020, a group of civil servants, together with waste collectors from Selikor, marched to Fort Amsterdam and demanded to speak with Rhuggenaath.[49] The demonstration turned into a riot, and police cleared the square in front of Fort Amsterdam[50] with tear gas.[51] The city centre of Willemstad was later looted.[50] 48 people were arrested,[52] the city districts of Punda and Otrobanda were placed under lockdown for the night, and a general curfew was declared from 20:30 to 06:00.[53]

Geography

editCuraçao, lies on the continental shelf of South America featuring a hilly topography, with its highest point reaching 372 m (1,220 ft) above sea level.[54] named Christoffelberg. Curaçao has diverse range of beaches from coastline's bays, inlets, lagoons, seasonal lakes, rough seas at its northshore, and a spring water. In addition, Curaçao has upwelling which is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler and nutrient-rich water from deep ocean moving towards the ocean surface, contributing to the source of natural minerals, thermal conditions, and seawater used in hydrotherapy and mesotherapy, making the island one of many balneoclimateric areas in the region. Furthemore, off the southeast coast of the main island of Curaçao lies the tiny unhabitated Isle of Klein Curaçao.[12] Klein Curaçao boasts long stretched beach.

Flora

editCuraçao's flora differ from typical tropical island vegetation. Guajira-Barranquilla xeric scrub is the most notable, with various forms of cacti, thorny shrubs, evergreen, and watapana trees (Libidibia coriaria; called divi-divi on Aruba), which are characteristic of the ABC islands and the national symbol of Aruba. Brassavola nodosa is a drought-tolerant species of Brassavola, one of the few orchids present in the ABC islands. Cacti include Melocactus and Opuntia species such as Opuntia stricta.[citation needed]

Fauna

editCuraçao is semi-arid, and as such has not supported the numerous tropical species of mammals, birds, and lizards most associated with rainforests. Dozens of species of hummingbirds, bananaquits, orioles, and the larger terns, herons, egrets, and even flamingos make their homes near ponds or in coastal areas. The trupial, a black bird with a bright orange underbelly and white swatches on its wings, is common to Curaçao. The mockingbird, called chuchubi in Papiamentu, resembles the North American mockingbird, with a long white-grey tail and a grey back. Near shorelines, big-billed brown pelicans feed on fish. Other seabirds include several types of gulls and large cormorants.[55]

Other than field mice, small rabbits, and cave bats, Curaçao's most notable animal is the white-tailed deer. This deer is related to the American white-tailed deer, or Virginia deer, found in areas from North America through Central America and the Caribbean, and as far south as Bolivia. It can be a large deer, some reaching six feet (2 m) in length and three feet (0.9 m) in height, and weighing as much as 300 pounds (140 kg). It has a long tail with a white underside, and is the only type of deer on the island. It has been a protected species since 1926, and an estimated 200 live on Curaçao. They are found in many parts of the island, but most notably at the west end's Christoffel Park, where about 70% of the herd resides. Archaeologists believe the deer were brought from South America to Curaçao by its original inhabitants, the Arawaks.[citation needed]

There are several species of iguana, light green in colour with shimmering shades of aqua along the belly and sides, found lounging in the sun across the island. The iguanas found on Curaçao serve not only as a scenic attraction but, unlike many islands that gave up the practice years ago, remain hunted for food. Along the west end of the island's north shore are several inlets that have become home to breeding sea turtles. These turtles are protected by the park system in Shete Boka Park, and can be visited accompanied by park rangers.[citation needed]

Climate

editCuraçao has a hot, semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh) with a dry season from January to September and a wet season from October to December.[56] Rainfall is scarce, only 450 millimeters (12 inches) per year; in particular, the rainy season is drier than it normally is in tropical climates; during the dry season, it almost never rains. Owing to the scarcity of rainfall, the landscape of Curaçao is arid; especially on the north coast of the island. Temperatures are relatively constant, with small differences measured throughout the year. The trade winds cool the island during the day and warm it at night. The coolest month is January with an average temperature of 26.6 °C or 80 °F; the hottest is September with an average temperature of 29.1 °C or 84 °F. The year's average maximum temperature is 31.4 °C or 89 °F. The year's average temperature is 25.7 °C or 78 °F. The seawater around Curaçao averages around 27 °C (81 °F) and is coolest (avg. 25.9 °C [78.6 °F]) from February to March, and hottest (avg. 28.2 °C [82.8 °F]) from September to October.[citation needed]

Because Curaçao lies North of the Intertropical Convergence Zone and in an area of low-level divergence where winds flow parallel to the coast, its climate is much drier than expected for the northeastern side of a continent at its latitude. Rainfall is also extremely variable from year to year,[57] being strongly linked to the El Niño Southern Oscillation. As little as 200 millimetres or 8 inches may fall in a strong El Niño year, but as much as 1,150 millimetres or 45 inches is not unknown in powerful La Niña years.

Curaçao lies outside the Main Development Region for tropical cyclones, but is still occasionally affected by them, as with Hurricanes Hazel in 1954, Anna in 1961, Felix in 2007, and Omar in 2008. No hurricane has made landfall in Curaçao since the US National Hurricane Center started tracking hurricanes. Curaçao has, however, been directly affected by pre-hurricane tropical storms several times; the latest being Hurricane Tomas in 2010, Cesar in 1996, Joan in 1988, Cora and Greta in 1978, Edith and Irene in 1971, and Francelia in 1969. Tomas brushed past Curaçao as a tropical storm, dropping as much as 265 mm (10.4 in) of rain on the island, nearly half its annual precipitation in a single day.[58] This made Tomas one of the wettest events in the island's history,[59] as well as one of the most devastating; its flooding killed two people and caused over NAƒ50 million (US$28 million) in damage.[60][61]

According to the Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research, average carbon dioxide emissions per person on the island were 52 tonnes in 2018, the second highest in the world.[62]

Meteo, the Curaçao weather department, provides up-to-date information about weather conditions via its website and mobile apps for iOS and Android.[63]

| Climate data for Curaçao - Hato International airport (TNCC) (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.3 (91.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.7 (94.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.5 (99.5) |

35.0 (95.0) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.3 (100.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.3 (91.9) |

38.3 (100.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.4 (88.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.6 (79.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29.1 (84.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.4 (75.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 21.5 (70.7) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 46.0 (1.81) |

28.8 (1.13) |

14.1 (0.56) |

19.4 (0.76) |

21.3 (0.84) |

22.4 (0.88) |

41.3 (1.63) |

39.7 (1.56) |

49.1 (1.93) |

102.0 (4.02) |

122.4 (4.82) |

95.5 (3.76) |

602.0 (23.70) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.5 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 8.1 | 10.9 | 11.4 | 70.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.5 | 78.2 | 77.3 | 78.2 | 77.9 | 77.5 | 78.1 | 77.8 | 78.1 | 79.6 | 80.6 | 79.5 | 78.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 264.7 | 249.6 | 271.8 | 249.4 | 266.3 | 266.7 | 290.4 | 302.5 | 261.7 | 247.8 | 234.7 | 247.1 | 3,152.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 73.8 | 75.2 | 72.8 | 67.0 | 67.9 | 70.8 | 73.3 | 78.2 | 71.6 | 67.4 | 67.6 | 69.8 | 71.3 |

| Source: Meteorological Department Curacao[64] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

editAverage temperatures have risen sharply in the past 40 years in the Caribbean Netherlands and Curaçao has experienced more warm days and fewer cooler nights.[65] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that should air temperatures increase by 1.4 degrees, there will be a 5% to 6% decrease in rainfall, increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events (including a 66% increase in hurricane intensity), and a 0.5- to 0.6-meter sea-level rise in the Caribbean Netherlands.[65]

Geology

editThe northern seabed drops steeply within 60 m (200 ft) of the Curaçaoan shore. This drop-off is known as the "blue edge".

On Curaçao, four major geological formations can be found: the lava formation, the Knip formation, the Mid-Curaçao formation and limestone formations.[66]

Curaçao lies within the Caribbean large igneous province (CLIP) with key exposures of those lavas existing on the island consisting of the Curaçao Lava Formation (CLF). The CLF consists of 5 km of pillow lavas with some basalt intrusions. The ages of these rocks include 89 Ma for the lavas and 75 Ma for the poikilitic sills, though some sequences may have erupted as late as 62–66 Ma, placing them in the Cretaceous period. Their composition includes picrite pillows at the base, followed by tholeiitic lavas, then hyaloclastites, then the poikilitic sills. The CLF was gradually uplifted until Eocene-Miocene limestone caps formed, before final exposure above sea level. Christoffelberg and the Zevenbergen (Seven Hills) portion of the island have exposures of the Knip Formation. This formation includes deepwater deposits of calcareous sands and fine clays, capped by siliceous chert containing radiolarians. Middle Curaçao contains alluvial soils from eroded CLF and limestone.[67][68]

Beaches

editCuraçao has 37 beaches.[69] Most are on the south side of the island. The best known are:

- Baya Beach

- Blue Bay

- Boca Sami

- Daaibooi

- Grote Knip (Kenepa Grandi)

- Kleine Knip (Kenepa Chiki)

- Kokomo Beach

- Mambo Beach

- Piscaderabaai

- Playa Forti

- Playa Jeremi

- Playa Kas Abao

- Playa Kalki

- Playa Kanoa

- Playa Lagun

- Playa Porto Marie

- Playa Santa Cruz

- Playa Santa Barbara

- Seaquarium Beach

- Sint Michielsbaai

- Vaersenbaai

- Westpunt

Architecture

editThe island has diverse architectural styles reflecting the influence of the various historical rulers over the region, including Spain, the Netherlands, with more modern elements under Western influence primarily including the United States and other European countries. This ranges from ruins and colonial buildings to modern infrastructure.

Forts

editWhen the Dutch arrived in 1634, they built forts at key points around the island to protect themselves from foreign powers, privateers, and pirates. Six of the best-preserved forts can still be seen today:

- Fort Amsterdam (1635)

- Fort Beekenburg (1703)

- Fort Nassau (1797)

- Waterfort (1826)

- Rif Fort (1828)[70]

- Fort Piscadera (built between 1701 and 1704)

In 1957, the hotel Van der Valk Plaza Curaçao was built on top of the Waterfort.[71]

The Rif Fort is located opposite of the Waterfort, across the Otrobanda harbour entrance. It contains restaurants and shops, and in 2009, the Renaissance Curaçao Resort and Casino opened next to it.[72][73]

Government

editCuraçao is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[12] Its governance takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democracy. The King of the Netherlands is the head of state, represented locally by a governor, with the Prime Minister of Curaçao serving as head of government.[12] Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament.[citation needed]

The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. Convicted felons are held at the Curaçao Centre for Detention and Correction.[citation needed]

Curaçao has full autonomy over most matters; the exceptions are outlined in the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands under the title "Kingdom affairs".[citation needed]

Military

editDefence of the island is the responsibility of the Netherlands.[12] The Netherlands Armed Forces deploy both ground and naval units in the Caribbean with some of these forces based on Curaçao. These forces include:

- a company of the Royal Netherlands Army on Curaçao on a rotational basis;

- a Fast Raiding Interception and Special Forces Craft (FRISC) troop (fast boats);

- a guardship, normally a Holland-class offshore patrol vessel, from the Royal Netherlands Navy on station in the Caribbean on a rotational basis;

- the Royal Netherlands Navy support vessel HNLMS Pelikaan;

- Curmil (Curaçaoan) militia elements;

- Elements of a Royal Marechaussee brigade of the Armed Forces.[74]

Two Dutch naval bases, Parera and Suffisant, are located on the island of Curaçao.[75] Officers of the Arubaanse Militie complete additional training on Curaçao.[citation needed] The Curaçao Volunteer Corps is also stationed at the Suffisant Naval Barracks.[74]

On the west side of Curaçao International Airport are hangars for the two Bombardier Dash 8 Maritime Patrol Aircraft and two AgustaWestland AW139 helicopters of the Dutch Caribbean Coast Guard. Until 2007, the site was a Royal Netherlands Navy air base which operated for 55 years with a wide variety of aircraft, including Fireflies, Avengers, Trackers, Neptunes, Fokker F-27s, P-3C Orions, Fokker F-60s and several helicopter types. After the political decision to sell off all Orions, the air base wasn't needed anymore.[citation needed]

The west end of the airport is a USAF Forward Operating Location (FOL).[76] The base hosts Airborne Warning And Control System (AWACS), cargo aircraft, aerial refueling planes, and reconnaissance aircraft.[76] Until 1999, the USAF operated a small fleet of F-16 fighters from the FOL.[citation needed] The PAE corporation runs base operations at the FOL.[77]

Conscription

editSuffisant Naval Base has facilities used for conscription in the Caribbean. There has been no military conscription since 1997, but a form of civil conscription has replaced it, compelling underprivileged young Antilleans to undertake professional training.[78]

Politics

editAfter being part of the Netherlands Antilles, Curaçao became autonomous, along with Sint Maarten island, while the less populated islands of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba remained special municipalities governed by the Netherlands.[79]

Economy

editCuraçao has an open economy; its most important sectors are tourism, international trade, shipping services, oil refining,[80] oil storage and bunkering, and international financial services.[12] Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA's lease on the island's oil refinery expired in 2019; the facility employs 1,000 people, refining oil from Venezuela for export to the US and Asia.[81] Schlumberger, the world's largest oil field services company, is incorporated in Curaçao.[82] The Isla oil refinery is said to be responsible for Curaçao's position as one of the world's top five highest per capita CO2 emission-producing countries.[83]

Along with Sint Maarten, Curaçao uses the Netherlands Antillean guilder as its currency.[12] Its economy is well-developed, supporting a high standard of living, ranking 46th in the world in terms of GDP (PPP) per capita and 27th in the world in terms of nominal GDP per capita. Curaçao possesses a high-income economy as defined by the World Bank.[84][85] Activities related to the port of Willemstad, such as the Free Trade Zone, make significant contributions to the economy.[12] To achieve greater economic diversification, the Curaçaoan government is increasing its efforts to attract more foreign investment.[12] This policy, called the "Open Arms" policy, features a heavy focus on attracting information technology companies.[86][87][88]

Since 2016, reduced foreign demand for goods due to the ongoing unrest and political uncertainty in Venezuela has led to decreased exports and increased domestic demand for goods and services, resulting in economic stagnation. While many economic sectors contracted, expansion took place in the construction, financial intermediation, and utilities sectors.[89]

Tourism

editWhile tourism plays a major role in Curaçao's economy, the island is less reliant on tourism than many other Caribbean countries. Most tourists come to Curaçao from the Netherlands, the eastern United States, South America and other Caribbean islands.[citation needed] Curaçao was a Caribbean leader in cruise ship tourism growth, with 610,186 cruise passengers in 2013, a 41.4% increase over the previous year.[90] Hato International Airport received 1,772,501 passengers in 2013 and announced capital investments totaling US$48 million aimed at transforming the airport into a regional hub by 2018.

The Curaçaoan insular shelf's sharp drop-off known as the "Blue Edge" is often visited by scuba diving tourists.[91] Coral reefs for snorkeling and scuba diving can be reached without a boat. The southern coast has calm waters as well as many small beaches, such as Jan Thiel and Cas Abou. At the westernmost point of the island is Watamula and the Cliff Villa Peninsula which are good locations for drift diving. The coastline of Curaçao features numerous bays and inlets which serve as popular mooring locations for boats.[92]

In June 2017, the island was named the Top Cruise Destination in the Southern Caribbean by Cruise Critic, a major online forum. The winners of the Destination Awards were selected based on comments from cruise passengers who rated the downtown area of Willemstad as "amazing" and the food and shopping as "excellent".[93] The historic centre of Willemstad is a World Heritage Site. Another attraction is the towns colourful street art. the Blue Bay Sculpture Garden with works from known Curaçao artists is situated in a nearby resort.[94] Landhuis Bloemhof is an art museum and gallery located in Willemstad.[95]

Some of the coral reefs are affected by tourism. Porto Marie Beach is experimenting with artificial coral reefs in order to improve the reef's condition.[citation needed] Hundreds of artificial coral blocks that have been placed are now home to a large array of tropical fish. It is now under investigation to see if the sewer waste of hotels is a partial cause of the dying of the coral reef.[96]

Labour

editIn 2016, a Labour Force Survey (LFS) indicated that the unemployment rate was 13.3%. For residents ages 15–64, the employment rate was 70.4%.[97][98]

Financial services

editCuraçao's history in financial services dates back to World War I. Prior to this period, the financial arms of local merchant houses functioned as informal lenders to the community. However, at the turn of the 20th century, Curaçao underwent industrialization, and a number of merchant houses established private commercial banks.[99] As the economy grew, these banks began assuming additional functions eventually becoming full-fledged financial institutions.

The Dutch Caribbean Securities Exchange is located in the capital of Willemstad, as is the Central Bank of Curaçao and Sint Maarten; the latter of which dates to 1828. It is the oldest central bank in the Western Hemisphere.[100] The island's legal system supports a variety of corporate structures and is a corporate haven. Though Curaçao is considered a tax haven, it adheres to the EU Code of Conduct against harmful tax practices. It holds a qualified intermediary status from the United States Internal Revenue Service. It is an accepted jurisdiction of the OECD and Caribbean Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering. The country enforces Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism funding compliance.[citation needed]

Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act

editOn 30 June 2014, Curaçao[101] was deemed to have an Inter-Governmental Agreement (IGA) with the United States of America with respect to the "Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act" of the United States of America. The Tax Information Exchange Agreement signed in Washington, D.C., on 17 April 2002[102] between the U.S. and the Kingdom of the Netherlands includes Curaçao, and was updated with respect to Curaçao in 2014, taking effect in 2016.

Trade

editCuraçao trades mainly with the United States, Venezuela, and the European Union. It has an Association Agreement with the European Union which allows companies which do business in and via Curaçao to export products to European markets,[103] free of import duties and quotas. It is also a participant in the US Caribbean Basin Initiative allowing it to have preferential access to the US market.[104]

Prostitution

editProstitution in Curaçao is legal only for foreign women who get a temporary permit to work in the large open-air brothel called "Le Mirage" or "Campo Alegre". Using prostitution services is legal for men (locals included). The brothel has operated near the airport since the 1940s.[105][106] Curaçao monitors, contains and regulates the industry. The government states that the workers in these establishments are thereby given a safe environment and access to medical practitioners. However this approach does exclude local women (or men) to legally make a living from prostitution and does lead to loss of local income, as the foreign prostitutes send or take most of their earnings home.[107]

Developments of Campo Alegre (2020-2024)

editSince its closure in 2020 after 71 years of operation, Campo Alegre, Curaçao's largest open-air brothel, has been at the center of significant developments. Following the closure, a government-appointed working group proposed three scenarios for the site: transforming it into a regulated prostitution area, repurposing it for commercial use, or converting it into a residential area.[108]

In 2023, the property was put up for auction, attracting various potential buyers.[109] In a significant move, the Curaçao government purchased the Campo Alegre property, aiming to have more control over its future use.[110]

The current ruling political party, Movement for the Future of Curaçao (MFK), had made an election promise to reopen Campo Alegre as a regulated prostitution center. This promise aligns with the recommendations of the working group and reflects the party's stance on creating a controlled environment for sex work.

As of 2024, the government is evaluating scenarios to ensure that the chosen path will benefit the local economy and social landscape.

The U.S. State Department has cited anecdotal evidence claiming that, "Curaçao...[is a] destination island... for women trafficked for the sex trade from Peru, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti, according to local observers. At least 500 foreign women reportedly are in prostitution throughout the five islands of the Antilles, some of whom have been trafficked."[111] The US Department of State has said that the government of Curaçao frequently underestimates the extent of human trafficking problems.[111]

Demographics

editOwing to the island's history of colonial times, the majority of the Curaçaoans are of African, or partial African descent.[12] There are also many Curaçaoans and immigrants of Dutch, French, Portuguese, Latin American, South Asian, East Asian, and Levantine descent on the island.[112]

Religion

edit- Religion in Curaçao[113]

The religious breakdown of the population of Curaçao, according to a 2011 estimate:[113]

- Roman Catholic;[113] 69.8%

- Adventist;[113] 9%

- Evangelical;[113] 8.9%

- Pentecostal;[113] 7.6%

- Other Protestant;[113] 3.2%

- Jehovah's Witnesses;[113] 2%

- Other;[113] 3.8%

- None;[113] 10%

- Unspecified;[113] 0.6%

There has been a shift towards the Charismatic movement in recent decades. Other denominations include the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the Methodist Church. Alongside these Christian denominations, some inhabitants practise Montamentu and other diaspora African religions.[114] As elsewhere in Latin America, Pentecostalism is on the rise.[citation needed] There are also practising Muslims and Hindus.

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Willemstad encompasses all the territory of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean which includes Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, and the islands of Bonaire, St. Eustatius and Saba. The diocese is also a member of the Antilles Episcopal Conference.[citation needed]

While small, Curaçao's Jewish community has had a significant impact on the island's history.[22] Curaçao has the oldest active Jewish congregation in the Americas, dating to 1651. The Curaçao synagogue is the oldest synagogue of the Americas in continuous use, since its completion in 1732 on the site of a previous synagogue.[115] Additionally, there are both Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jewish communities.[12] As of the year 2000 there were approximately 300 Jewish people living on the island.[116]

Languages

editCuraçao is a multilingual society. The official languages are Dutch, Papiamentu and English.[117][12] However, Dutch is the sole language for all administration and legal matters.[118] Most of Curaçao's population is able to converse in at least two, though more commonly in all four of the languages of Papiamentu, Dutch, English, and Spanish.[citation needed]

The most widely spoken language is Papiamentu, a Portuguese creole with African, Dutch and Spanish influences, spoken in all levels of society.[12] Papiamentu was introduced as a language of primary school education in 1993, making Curaçao one of a handful of places where a creole language is used as a medium to acquire basic literacy.[119] Spanish and English also have a long historical presence in Curaçao. Spanish became an important language in the 18th century due to the close economic ties with Spanish territories in what are now Venezuela and Colombia[30] and several Venezuelan TV networks are received. Use of English dates to the early 19th century, when the British occupied Curaçao, Aruba and Bonaire. When Dutch rule resumed in 1815, officials already noted the widespread use of the English language.[30]

According to the 2001 census, Papiamentu was the first language of 81.2% of the population. Dutch of 8%, Spanish of 4%, and English of 2.9%.[120] However, these numbers divide the population in terms of first language and do not account for the high rate of bilingualism in the population of Curaçao.[citation needed]

Localities

editCuraçao was divided into five districts from 1863 to 1925, after which it was reduced to the two outer districts of Bandabou and Bandariba and the city district of Willemstad. Over the years, the capital, Willemstad, encompassed the entire area surrounding the large natural harbour, the Schottegat. As a result, many formerly isolated villages have grown together to form a large urbanised area. The city covers approximately one third of the entire island in the east. Willemstad's most famous neighbourhoods are:

- Punda, the historic city centre with the Handelskade on St. Anna Bay.

- Otrobanda, on the other side of St. Anna Bay

- Pietermaai, east of Punda

- Scharloo, north of Punda and Pietermaai, across the Waaigat

- Julianadorp, a suburb on the west side of the city, built around 1928 on behalf of Shell for its personnel

- Emmastad, built for Shell in the 1950s, after Julianadorp was full.

- Saliña is situated next to Punda and has many shops and restaurants.

- Brievengat, a suburb in the north of the city.

Structure of the population

edit| Age Group | Male | Female | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 69 285 | 83 084 | 152 369 | 100 |

| 0–4 | 3 876 | 3 637 | 7 513 | 4.93 |

| 5–9 | 4 750 | 4 479 | 9 229 | 6.06 |

| 10–14 | 4 487 | 4 401 | 8 888 | 5.83 |

| 15–19 | 4 503 | 4 393 | 8 895 | 5.84 |

| 20–24 | 3 891 | 3 665 | 7 556 | 4.96 |

| 25–29 | 3 862 | 4 280 | 8 142 | 5.34 |

| 30–34 | 3 966 | 4 774 | 8 740 | 5.74 |

| 35–39 | 4 081 | 5 091 | 9 172 | 6.02 |

| 40–44 | 3 833 | 5 099 | 8 932 | 5.86 |

| 45–49 | 4 563 | 5 790 | 10 353 | 6.79 |

| 50–54 | 5 049 | 6 323 | 11 372 | 7.46 |

| 55–59 | 5 481 | 7 013 | 12 493 | 8.20 |

| 60–64 | 4 937 | 6 576 | 11 513 | 7.56 |

| 65–69 | 4 098 | 5 523 | 9 621 | 6.31 |

| 70–74 | 3 427 | 4 506 | 7 932 | 5.21 |

| 75–79 | 2 163 | 3 342 | 5 504 | 3.61 |

| 80–84 | 1 346 | 2 146 | 3 492 | 2.29 |

| 85–89 | 661 | 1 283 | 1 944 | 1.28 |

| 90–94 | 248 | 543 | 791 | 0.52 |

| 95–99 | 59 | 192 | 250 | 0.16 |

| 100+ | 8 | 35 | 43 | 0.03 |

| Age group | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| 0–14 | 13 113 | 12 517 | 25 630 | 16.82 |

| 15–64 | 44 162 | 52 997 | 97 159 | 63.77 |

| 65+ | 12 010 | 17 570 | 29 580 | 19.41 |

Statistics

editEducation

editPublic education is based on the Dutch educational system and besides the public schools, private and parochial schools are also available. Since the introduction of a new public education law in 1992, compulsory primary education starts at age six and continues for six years; secondary lasts for another four.[122]

The main institute of higher learning is the University of Curaçao (formerly University of The Netherlands Antilles), enrolling 2,100 students.[122] The comprehensive model of education is influenced by both the Dutch and American education systems. Other higher education offerings on the island include offshore medical schools, universities, language schools and academies for fine art, music, police, teacher and nurse-training.[123]

Culture

editVisual art

editVisual art in Curaçao encompasses painting, sculptures, and street art.[124]

Curaçao promotes street art with a festival, Kaya Kaya, held in the Otrabanda neighborhood of Willemstad.[125] The streets of Willemstad are filled with murals from multiple versions of the festival.

Literature

editDespite the island's relatively small population, the diversity of languages and cultural influences on Curaçao have generated a remarkable literary tradition, primarily in Dutch and Papiamentu. The oral traditions of the Arawak indigenous peoples are lost. West African slaves brought the tales of Anansi, thus forming the basis of Papiamentu literature. The first published work in Papiamentu was a poem by Joseph Sickman Corsen entitled Atardi, published in the La Cruz newspaper in 1905.[citation needed] Throughout Curaçaoan literature, narrative techniques and metaphors best characterized as magic realism tend to predominate. Novelists and poets from Curaçao have contributed to Caribbean and Dutch literature. Best known are Cola Debrot, Frank Martinus Arion, Pierre Lauffer, Elis Juliana, Guillermo Rosario, Boeli van Leeuwen and Tip Marugg.[citation needed]

Cuisine

editLocal food is called Krioyo (pronounced the same as criollo, the Spanish word for "Creole") and boasts a blend of flavours and techniques best compared to Caribbean cuisine and Latin American cuisine. Dishes common in Curaçao are found in Aruba and Bonaire as well. Popular dishes include stobá (a stew made with various ingredients such as papaya, beef or goat), Guiambo (soup made from okra and seafood), kadushi (cactus soup), sopi mondongo (intestine soup), funchi (cornmeal paste similar to fufu, ugali and polenta) and fish and other seafood. The ubiquitous side dish is fried plantain. Local bread rolls are made according to a Portuguese recipe. All around the island, there are snèks which serve local dishes as well as alcoholic drinks in a manner akin to the English pub.[citation needed]

The ubiquitous breakfast dish is pastechi: fried pastry with fillings of cheese, tuna, ham, or ground meat. Around the holiday season special dishes are consumed, such as the hallaca and pekelé, made out of salt cod. At weddings and other special occasions a variety of kos dushi are served: kokada (coconut sweets), ko'i lechi (condensed milk and sugar sweet) and tentalaria (peanut sweets). The Curaçao liqueur was developed here, when a local experimented with the rinds of the local citrus fruit known as laraha. Surinamese, Chinese, Indonesian, Indian and Dutch culinary influences also abound. The island also has a number of Chinese restaurants that serve mainly Indonesian dishes such as satay, nasi goreng and lumpia (which are all Indonesian names for the dishes). Dutch specialties such as croquettes and oliebollen are widely served in homes and restaurants.[citation needed]

Sports

editIn 2004, the Little League Baseball team from Willemstad, Curaçao, won the world title in a game against the United States champion from Thousand Oaks, California. The Willemstad lineup included Jurickson Profar, the standout shortstop prospect who now plays for the San Diego Padres of Major League Baseball, and Jonathan Schoop.[126]

Curaçaoan players Andruw Jones,[127] Ozzie Albies, and Kenley Jansen have made multiple Major League Baseball All-Star Game appearances.[128]

The 2010 documentary film Boys of Summer[129] details Curaçao's Pabao Little League All-Stars winning their country's eighth straight championship at the 2008 Little League World Series, then going on to defeat other teams, including Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, and earning a spot in Williamsport.[130]

The prevailing trade winds and warm water make Curaçao a location for windsurfing.[131][132]

There is warm, clear water around the island. Scuba divers and snorkelers may have visibility up to 30 metres (98 feet) at the Curaçao Underwater Marine Park, which stretches along 20 kilometres (12 miles) of Curaçao's southern coastline.[133]

Curaçao participated in the 2013 CARIFTA Games. Kevin Philbert stood third in the under-20 male Long Jump with a distance of 7.36 metres (24.15 feet). Vanessa Philbert stood second the under-17 female 1,500 metres (4,900 feet) with a time of 4:47.97.[134][135][136][137]

The Curaçao national football team won the 2017 Caribbean Cup by defeating Jamaica in the final, qualifying for the 2017 CONCACAF Gold Cup.[138] They then traveled to Thailand and participated in the 2019 King's Cup for the first time, eventually winning the tournament by beating Vietnam in the final.[139]

Infrastructure

editAirport

editCuraçao International Airport (also called Hato International Airport) is located on the northern coast of the island and offers connections to the Caribbean region, South America, North America and Europe. Curaçao Airport is a fairly large facility, with the third longest commercial runway in the Caribbean region after Rafael Hernández Airport in Puerto Rico and Pointe-à-Pitre International Airport in Guadeloupe. The airport served as a main base for Insel Air, and for Air ALM, the former national airlines of Curaçao.[citation needed]

Railways

editIn 1887 a horse drawn street tramway opened in Punda, the part of the capital Willemstad on the eastern side of Sint Annabaai. It had a U-shaped route about 2 km in length. In 1896, a tramway opened in Otrabanda on the opposite side of the bay, but it ceased operations within a few months. The Punda line was rebuilt in 1911, regauged to metre gauge, and the horse-drawn trams replaced by petrol engined ones. The line closed in 1920.[140]

Bridges

editThe Queen Emma Bridge, a 168 metres (551 ft) long pontoon bridge, allows pedestrians to walk between the Punda and Otrobanda districts.[141] This swings open to allow the passage of ships to and from the port.[142] The bridge was originally opened in 1888 and the current bridge was installed in 1939.[143] It is best known and, more often than not, referred to by the locals as "Our Swinging Old Lady".[144]

The Queen Juliana Bridge carries motor vehicle traffic between the same two districts and its 1974 opening allowed the Queen Emma Bridge to become a pedestrian-only bridge. At 185 feet (56 m) above the sea, the Queen Juliana Bridge is one of the highest bridges in the Caribbean.[142]

Utilities and sanitation

editAqualectra, a government-owned company[145] and a full member of CARILEC, delivers potable water and electricity to the island. Rates are controlled by the government. Water is produced by reverse osmosis or desalinization.[146] It services 69,000 households and companies using 130,000 water and electric meters.[146] The power generation company NuCuraçao opened wind farms in Tera Kora and Playa Kanoa in 2012, and expanded in Tera Kora in 2015.[147] There is no natural gas distribution grid; gas is supplied to homes by pressurized containers.[148]

Curbside trash pickup is provided by the Selikor company. There is no recycling pickup, but there are drop-off centers for certain recycled materials at the Malpais landfill,[149] and various locations operated by Green Force;[150][151] private haulers recycle construction waste, paper, and cardboard.[152][153][154]

Notable residents

editPeople from Curaçao include:

Arts and culture

edit- Izaline Calister, singer-songwriter

- Joceline Clemencia, writer

- Peter Hartman, past-CEO of KLM

- May Henriquez, writer and sculptor[155]

- Tip Marugg, writer[citation needed]

- Kizzy, a singer songwriter and television personality based in the United States[citation needed]

- Ruënna Mercelina, model, actress, beauty queen

- Robby Müller, cinematographer, closely associated with Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch[156]

- Wim Statius Muller, composer, pianist[157]

- Pernell Saturnino, a graduated percussionist of Berklee College of Music[158]

- Sherman Smith (musician), singer-songwriter

- Ellen Spijkstra, ceramist

- Siny van Iterson, children's writer

Politics and government

edit- Luis Brión, admiral in the Venezuelan War of Independence

- Moises Frumencio da Costa Gomez, first Prime Minister of the Netherlands Antilles

- George Maduro, a war hero and namesake of Madurodam in The Hague

- Manuel Carlos Piar, general and competitor of Bolivar during the Venezuelan War of Independence

- Tula, leader of the 1795 slave revolt

- Daniël Corsen, Chairperson of the World Scout Committee

Sports

editBaseball

editPlayers in Major League Baseball:

- Ozzie Albies, professional second baseman[159]

- Wladimir Balentien, professional outfielder[160]

- Roger Bernadina, professional outfielder[161]

- Didi Gregorius, professional shortstop[162]

- Kenley Jansen, professional pitcher[163]

- Andruw Jones, professional outfielder[164]

- Jair Jurrjens, professional pitcher[165]

- Shairon Martis, professional pitcher[166]

- Hensley Meulens, professional baseball player and hitting coach[167]

- Jurickson Profar, professional outfielder[168]

- Ceddanne Rafaela, professional outfielder[169]

- Jonathan Schoop, professional infielder[170]

- Andrelton Simmons, professional shortstop[171]

- Randall Simon, first baseman[172]

Football

edit- Vurnon Anita, a football player for Al-Orobah FC in the Saudi Arabian First Division[173]

- Juninho Bacuna, footballer playing for Al Wehda in the Saudi Professional League.

- Leandro Bacuna, footballer playing for FC Groningen in the Dutch Eerste Divisie.

- Roly Bonevacia, a footballer who plays for Al-Faisaly in the Saudi Professional League[174]

- Tahith Chong, a footballer playing for Luton Town in the English Premier League.

- Juriën Gaari, footballer playing for RKC Waalwijk in the Dutch Eredivisie.

- Sontje Hansen, footballer playing for NEC Nijmegen in the Dutch Eredivisie.

- Rangelo Janga, a footballer who plays for Bnei Sakhnin in the Israeli Premier League.

- Jürgen Locadia, footballer playing for Cangzhou Mighty Lions in the Chinese Super League.

- Cuco Martina, footballer playing for NAC Breda in the Dutch Eerste Divisie

- Roshon van Eijma, footballer playing for Top Oss in the Dutch Eerste Divisie

- Jeremy Antonisse, footballer playing for Moreirense in the Portuguese Primeira Liga.

- Darryl Lachman, footballer who plays for Perth Glory in the Australian A-League.

- Eloy Room, footballer playing for Vitesse Arnhem in the Dutch Eredivisie.

- Gino van Kessel, footballer playing for MFK Zemplín Michalovce in the Slovak Niké liga.

- Jetro Willems, footballer playing for Heracles Almelo in the Dutch Eredivisie.[175]

Other Sports

edit- Jemyma Betrian, professional mixed-martial-arts (MMA) fighter[176]

- Liemarvin Bonevacia, professional sprinter

- Marc de Maar, professional cyclist[177]

- Churandy Martina, gold medalist 100 metres at the Pan American Games 2007[178]

- Jordann Pikeur, professional kickboxer

- Jean-Julien Rojer, professional tennis player[179]

- Roelly Winklaar, IFBB pro bodybuilder

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Curacao". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Waaruit bestaat het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden?". Rijksoverheid (in Dutch). 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Population". Central Bureau of Statistics Curaçao. January 2023. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ van der Molen, Maarten (19 September 2013). "Country Report Curaçao". RaboResearch – Economic Research. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Curacao". The World Bank. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ Human Development Index (HDI): Korte Notitie inzake de berekening van de voorlopige Human Development Index (HDI) voor Curaçao (PDF) (in Dutch). Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 20 December 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 9781405881180.

- ^ "Curaçao". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Mangold, Max (2005). "Curaçao". In Franziska Münzberg (ed.). Aussprachewörterbuch. Mannheim: Duden Verlag. ISBN 978-3-411-04066-7.

- ^ "Art. 1 para 1 Constitution of Curaçao" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. (Dutch version)

- ^ "Art. 1 para 1 Constitution of Curaçao" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2009. (Papiamentu version)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "CIA World Factbook- Curaçao". Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook – Curaçao". Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Öörni, Juha (6 October 2017). "Traveler's Paradise - ABC Islands: Travel Guide for ABC Islands (Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao)".

- ^ (Dutch: Eilandgebied Curaçao, Papiamentu: Teritorio Insular di Kòrsou).

- ^ The English name is used by the governments of Curaçao and Netherlands Antilles, as English was an official language of the Netherlands Antilles and the Island Territory of Curaçao.

- ^ Joubert and Van Buurt, 1994

- ^ a b "Curaçao" Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Curaçao-nature.com, 2005–2016. Retrieved 12 August 2016

- ^ "Taino Names of the Caribbean Islands". 2 February 2015.

- ^ Cock's 1562 map, Library of Congress website

- ^ a b c d e f "The History of Curaçao". Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Curacao Virtual Jewish History Tour". jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ "The story of Curacao | History".

- ^ "Curaçao History". Papiamentu.net. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313332739.

- ^ "Octagon Museum – Curaçao Art".

- ^ "Curacao in the British Empire".

- ^ a b "The History of Curaçao". Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ^ Called "Paga Tera"

- ^ a b c Dede pikiña ku su bisiña: Papiamentu-Nederlands en de onverwerkt verleden tijd. van Putte, Florimon., 1999. Zutphen: de Walburg Pers

- ^ Van Putte 1999.

- ^ "Overval op fort Amsterdam in Willemstad op Curaçao door de Venezolaanse revolutionair Urbina (8 juni 1929)" (in Dutch). Ministry of Defense. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "WHKMLA: List of Wars of the Dutch Republic / Netherlands". 7 April 2024.

- ^ Anderson & Dynes 1975, p. 81, Oostindie & Klinkers 2013, p. 98, "Striking Oil Workers Burn, Loot in Curacao". Los Angeles Times. 31 May 1969, p. 2.

- ^ Anderson & Dynes 1975, pp. 100–101, Sharpe 2015, p. 122, Verton 1976, p. 90, "Nieuwe ministers legden eed af" (in Dutch). Amigoe di Curaçao. 12 December 1969, p. 1.

- ^ a b "Curaçao refinery sputters on, despite emissions". Reuters. 30 June 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ "The Dutch migration monitor: Backgrounds and developments of different types of international migration" (PDF). Wodc.nl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ The Daily Herald St. Maarten (9 July 2007). "Curaçao IC ratifies 2 November accord". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ Cuales, Orlando (15 May 2009). "Curacao Referendum Approves Increasing Autonomy". Newser. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ Koninkrijksrelaties, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en (13 December 2011). "New constitutional order – Caribbean Parts of the Kingdom – Government.nl". Government.nl. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "NOS Nieuws – Antillen opgeheven op 10-10-2010". Nos.nl. 18 November 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Status change means Dutch Antilles no longer exists". BBC News. 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Curaçao heeft een tussenkabinet, dat vooral moet bezuinigen" (in Dutch). 31 December 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Regering Curaçao beëdigd" (in Dutch). 7 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ "Curaçao Prime Minister wants to do business with the Netherlands". Curacaochronicle.com. 4 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Premier Rhuggenaath participates High Level Political Forum in New York". Curacaochronicle.com. 17 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "On numerous occasions the Netherlands has offered assistance with Oil Refinery negotiations". Curacaochronicle.com. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Protest Curaçao eindigt in rellen en plunderingen, avondklok ingesteld". Omroep NTR via Knispelkrant Curaçao (in Dutch). Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Angry protestors heading towards Fort Amsterdam". Curaçao Chronicle. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Plunderingen in Willemstad uitgaansverbod". Curacao.nu (in Dutch). 24 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Curaçao protest gets out of hand". The Daily Herald.sx. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "48 personen gearresteerd". Dolfijn FM (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 27 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Punda and Otrobanda in lockdown until Friday; Curfew tonight from 8:30pm until 6am". Curaçao Chronicle. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". cia.gov. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Prins, T. G.; Reuter, J. H.; Debrot, A. O.; Wattel, J.; Nijman, V. (October 2009). "Checklist of the Birds of Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire, South Caribbean". Ardea. 97 (2): 137–268. doi:10.5253/078.097.0201. ISSN 0373-2266.

- ^ "Climate Summaries". Meteorological Department Curaçao.

- ^ Dewar, Robert E. and Wallis, James R; ‘Geographical patterning in interannual rainfall variability in the tropics and near tropics: An L-moments approach’; in Journal of Climate, 12; pp. 3457–3466

- ^ "Doden door noodweer op Curaçao" (in Dutch). Netherlands National News Agency. 1 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ "Damdoorbraken in Curaçao door storm Tomas" (in Dutch). Nieuws.nl. 2 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Elisa Koek (6 November 2010). "50 miljoen schade" (in Dutch). versgeperst.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- ^ Redactie Aworaki (2 November 2010). "Twee doden op Curaçao door Tropische Storm Tomas". Aworaki.nl.

- ^ Fossil CO2 and GHG emissions of all world countries: 2019 report. Publications Office of the European Union. 26 September 2019. ISBN 9789276111009.

- ^ "Weather App". www.meteo.cw. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- ^ "Summary Climatological Data 1981–2010" (PDF). Meteorological Department Curacao. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Climate change becomes an existential crisis on the islands". Curacao Chronicle. 15 November 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ "CARMABI Research Station Curaçao". researchstationcarmabi.org.

- ^ Loewen, M.W.; Duncan, R.A.; Krawl, K.; Kent, A.J.; Sinton, C.W.; Lackey, J. (2011). "Prolonged volcanic history for the Curaçao Lava Formation inferred from new 40Ar-39Ar ages and trace phase geochemistry". American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2011, Abstract Id. V51D-2542. 2011: V51D–2542. Bibcode:2011AGUFM.V51D2542L.

- ^ van Buurt, Gerard (2010). "A Short Natural History of Curaçao. In: Crossing Shifting Boundaries, Language and Changing Political status in Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao" (PDF). Proceedings of the ECICC-conference, Dominica 2009. I: 229–256. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Ruepert, Maaike (25 November 2014). "De 37 stranden van Curaçao in kaart". Algemeen Dagblad (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ "Riffort". Riffortcuracao.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Kateman, Thijs (2012). Curacao, Aruba en Bonaire / druk 1: Binaire en Aruba. ANWB Media – Boeken & Gidsen. p. 70. ISBN 978-90-18-02464-2.

- ^ (2011) GEA Curaçao. Ref. AR 48811 – Aqua Spa B.V. vs Renaissance Curaçao Resort & Casino (Riffort Village N.V.) – Riffort Village Exploitatie Maatschappij N.V. – Aruba Bank N.V.

- ^ "Lien on Renaissance Bank Accounts", Amigoe Newspaper, 31 May 2011

- ^ a b "Units and locations - Caribbean territories - Defensie.nl". 3 June 2022.

- ^ "Commandement der Zeemacht Caribisch gebied". Defensie.nl.

- ^ a b "Curacao/Aruba Forward Operating Locations". 12th Air Force (Air Forces Southern). Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Contracts for October 30, 2020". U.S. DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Defensie, Ministerie van. "Commander Netherlands Forces in the Caribbean". defensie.nl. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Curacao profile". BBC News. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Dutch Caribbean Refineries on Uncertain Path – Carib Flame". Caribflame.com. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Curacao Economy 2017, CIA World Factbook". Theodora.com. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Schlumberger N.V. – Company Information".

- ^ "COP21 alert: Caribbean part of Dutch Kingdom belongs to top 5 CO2 emissions per capita | Stichting SMOC". www.stichtingsmoc.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ The World Bank. "Excel file of historical classifications by income". Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "How are the income group thresholds determined? – World Bank Data Help Desk". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "An investor's guide to the welcoming island of Curaçao" (PDF). Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Mindmagnet.com (1 March 2001). "Ecommerce at Curaçao Corporate". Ecommerceatcuracao.com. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ "Economic Data Overview". Investcuracao.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ "Economic Developments in 2016 and outlook for 2017 / Economische ontwikkelingen in 2016 en vooruitzichten voor 2017 – Curacao / Sint Maarten – BearingPoint Caribbean". Bearingpointcaribbean.com. 14 February 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Curaçao Leading Caribbean in Cruise Tourism Growth". Caribjournal.com. 14 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ "An Underwater Photographer's Guide to Curaçao". DivePhotoGuide. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Curacao vakantie – Curacao vakantie". Curacao vakantie (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ "Curaçao has been named the Top Cruise destination in the Southern Caribbean". Curacaochronicle.com. 27 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Blue Bay Beeldentuin". Curacao Art. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ "Landhuis Bloemhof". Beautiful Curaçao. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ NTR, Omroep. "Vernietigt toeristenpoep ons Nederlandse koraal?". NPO Focus.

- ^ "Statistics: "Unemployment rate rose to 13.3 percent"". Curacaochronicle.com. 1 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Supply Side of the Labour Market Curaçao: Labour Force Survey 2016 – BearingPoint Caribbean". Bearingpointcaribbean.com. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Private Banking – Roots of Our Future". caribseek.com. 11 December 2002. Archived from the original on 14 May 2003. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ^ "In 175 years the Bank has evolved from a near dormant institution in the nineteenth century to a vibrant organization able to adapt to the ever changing financial world in the twenty-first century". centralbank.an. 1 February 2003. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ U.S. Treasury FACTA.

- ^ U.S. Treasury Agreement with Curaçao (pdf).

- ^ "EU Trade Program". archive.org. 24 June 2007. Archived from the original on 24 June 2007.

- ^ "USTR – Caribbean Basin Initiative". Ustr.gov. 1 October 2000. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- ^ "Sex Tourism And Trafficking In The Dutch Caribbean". Curacao Chronicle. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- ^ "Curaçao Opens Campo Alegre Brothel". NSWP. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Curaçao's X-Rated Resort". Global Writes. 2009. Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Werkgroep adviseert regering over heropening bordeel". Antilliaans Dagblad. 2023.

- ^ "Campo Alegre, 's werelds grootste bordeel op het westelijk halfrond, gaat dinsdag onder de hamer". Curacao.nu. 2023.

- ^ "Groot openluchtbordeel Curaçao sluit na 71 jaar, maar voor hoelang?". NOS. 2020.

- ^ a b "Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. State Dept. 4 June 2008. p. 192.

- ^ "Eerste resultaten Census 2023" (PDF). cuatro.sim-cdn.nl. 4 June 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Central America and Caribbean: Curaçao". CIA The World Factbook. 19 October 2021.

- ^ Bernadina, Frieda (1981). Montamentoe: een beschrijvende en analyserende studie van een Afro-Amerikaanse godsdienst op Curaçao. Curaçao: Bernadina.

- ^ "Dwindling Community of Curacao Maintains Oldest Synagogue in West". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- ^ "The Jewish Community of Curacao". Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- ^ Landsverordening van de 28ste maart 2007 houdende vaststelling van de officiële talen (Landsverordening officiële talen) (in Dutch) – via Overheid.nl.

- ^ "About Us". DutchCaribbeanLegalPortal.com. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Anthony Liddicoat (15 June 2007). Language planning and policy: issues in language planning and literacy. Multilingual Matters. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-85359-977-4. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ "Households by the most spoken language in the household Population and Housing Census 2001". Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012.

- ^ "UNSD — Demographic and Social Statistics". unstats.un.org. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b Walton, R.H. (2006). Cold Case Homicides: Practical Investigative Techniques. CRC Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4200-0394-9.

- ^ Rosalind Latiner, Raby (2009). Community College Models: Globalization and Higher Education Reform. Springer. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-4020-9477-4. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Curaçao: The Caribbean Getaway That Sets You Free". www.curacao.com. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Kaya Kaya Festival". Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Curacao an island unto itself when it comes to producing big-league ballplayers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Atlanta Braves: It's time to retire Andruw Jones' number 25". calltothepen.com. 5 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Jansen's 3-K ninth highlights LA's ASG". MLB. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "Boys of Summer". Boysofsummerfilm.com. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "Boys of Summer: Documentary Spotlights Youth Baseball in Cuaraçao". Large Up. 10 March 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Curaçao's Caribbean sister islands, Aruba and Bonaire, are well known in the windsurfing world. Curaçao, which receives the same Caribbean trade winds as its siblings, has remained undiscovered by traveling windsurfers". Windsurfingcuracao.com. 7 August 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Motion Magazine, June 2005

- ^ "Frommers Guide to Curaçao water sports". The New York Times. 20 November 2006.

- ^ 42nd CARIFTA BAHAMAS in 2013 – 3/30/2013 to 4/1/2013 – T. A. ROBINSON NATIONAL TRACK & FIELD STADIUM – Nassau, Bahamas – Results, C.F.P.I. Timing & Data, retrieved 13 November 2013