The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times from the Lokono of South America to the Taíno, who lived in the Greater Antilles and northern Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. All these groups spoke related Arawakan languages.[1]

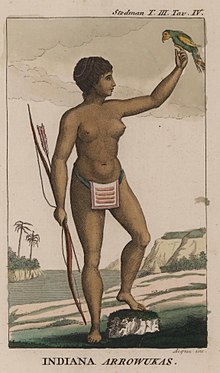

Arawak woman, by John Gabriel Stedman | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| South America, Caribbean | |

| Languages | |

| Arawak, Arawakan languages, Taino, Caribbean English, Caribbean Spanish, Creole languages | |

| Religion | |

| Native American religion, Christianity |

Name edit

Early Spanish explorers and administrators used the terms Arawak and Caribs to distinguish the peoples of the Caribbean, with Carib reserved for indigenous groups that they considered hostile and Arawak for groups that they considered friendly.[2]: 121

In 1871, ethnologist Daniel Garrison Brinton proposed calling the Caribbean populace "Island Arawak" because of their cultural and linguistic similarities with the mainland Arawak. Subsequent scholars shortened this convention to "Arawak", creating confusion between the island and mainland groups. In the 20th century, scholars such as Irving Rouse resumed using "Taíno" for the Caribbean group to emphasize their distinct culture and language.[1]

History edit

The Arawakan languages may have emerged in the Orinoco River valley in present-day Venezuela. They subsequently spread widely, becoming by far the most extensive language family in South America at the time of European contact, with speakers located in various areas along the Orinoco and Amazonian rivers and their tributaries.[3] The group that self-identified as the Arawak, also known as the Lokono, settled the coastal areas of what is now Guyana, Suriname, Grenada, Bahamas, Jamaica[4] and parts of the islands of Trinidad and Tobago.[1][5]

Michael Heckenberger, an anthropologist at the University of Florida who helped found the Central Amazon Project, and his team found elaborate pottery, ringed villages, raised fields, large mounds, and evidence for regional trade networks that are all indicators of a complex culture. There is also evidence that they modified the soil using various techniques such as adding charcoal to transform it into black earth, which even today is famed for its agricultural productivity. Maize and sweet potatoes were their main crops, though they also grew cassava and yautia. The Arawaks fished using nets made of fibers, bones, hooks, and harpoons. According to Heckenberger, pottery and other cultural traits show these people belonged to the Arawakan language family, a group that included the Tainos, the first Native Americans Columbus encountered. It was the largest language group that ever existed in the pre-Columbian Americas.[6]

At some point, the Arawakan-speaking Taíno culture emerged in the Caribbean. Two major models have been presented to account for the arrival of Taíno ancestors in the islands; the "Circum-Caribbean" model suggests an origin in the Colombian Andes connected to the Arhuaco people, while the Amazonian model supports an origin in the Amazon basin, where the Arawakan languages developed.[7] The Taíno were among the first American people to encounter Europeans. Christopher Columbus visited multiple islands and chiefdoms on his first voyage in 1492, which was followed by the establishment of La Navidad[8] that same year on the northeast coast of Hispaniola, the first Spanish settlement in the Americas. Relationships between the Spaniards and the Taíno would ultimately take a sour turn. Some of the lower-level chiefs of the Taíno appeared to have assigned a supernatural origin to the explorers. When Columbus returned to La Navidad on his second voyage, he found that the settlement had been burned down and all 39 men he had left there had been killed.[9]

With the establishment of a second settlement, La Isabella, and the discovery of gold deposits on the island, the Spanish settler population on Hispaniola started to grow substantially, while disease and conflict with the Spanish began to kill tens of thousands of Taíno every year. By 1504, the Spanish had overthrown the last of the Taíno cacique chiefdoms on Hispaniola, and firmly established the supreme authority of the Spanish colonists over the now-subjugated Taíno. Over the next decade, the Spanish colonists presided over a genocide of the remaining Taíno on Hispaniola, who suffered enslavement, massacres, or exposure to diseases.[8] The population of Hispaniola at the point of first European contact is estimated at between several hundred thousand to over a million people,[8] but by 1514, it had dropped to a mere 35,000.[8] By 1509, the Spanish had successfully conquered Puerto Rico and subjugated the approximately 30,000 Taíno inhabitants. By 1530, there were 1,148 Taíno left alive in Puerto Rico.[10]

Taíno influence has survived even until today, though, as can be seen in the religions, languages, and music of Caribbean cultures.[11] The Lokono and other South American groups resisted colonization for a longer period, and the Spanish remained unable to subdue them throughout the 16th century. In the early 17th century, they allied with the Spanish against the neighbouring Kalina (Caribs), who allied with the English and Dutch.[12] The Lokono benefited from trade with European powers into the early 19th century, but suffered thereafter from economic and social changes in their region, including the end of the plantation economy. Their population declined until the 20th century, when it began to increase again.[13]

Most of the Arawak of the Antilles died out or intermarried after the Spanish conquest. In South America, Arawakan-speaking groups are widespread, from southwest Brazil to the Guianas in the north, representing a wide range of cultures. They are found mostly in the tropical forest areas north of the Amazon. As with all Amazonian native peoples, contact with European settlement has led to culture change and depopulation among these groups.[14]

Modern population and descendants edit

The Spaniards who arrived in the Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic) in 1492, and later in Puerto Rico, brought few women on their first expeditions. Many of the explorers and early colonists raped Taíno women, who subsequently bore mestizo or mixed-race children. Over subsequent generations, the remnant Taíno population continued to mix with Spaniards and other Europeans, as well as with other indigenous groups and enslaved Africans brought over during the Atlantic slave trade. Today, numerous mixed-race descendants still identify as Taíno or Lokono.

In the 21st century, about 10,000 Lokono live primarily in the coastal areas of Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana, with additional Lokono living throughout the larger region. Unlike many indigenous groups in South America, the Lokono population is growing.[15]

Notable Arawak edit

- Damon Gerard Corrie, Barbados Lokono of Guyana Lokono descent, radical international indigenous rights activist, and creator of the militant Indigenous Democracy Defence Organization (IDDO), the only such global pan-tribal and multi-racial indigenous NGO in existence.[16] He is also the creator of the only Phonetic English to Arawak dictionary (2021),[17] and the only comprehensive books about Lokono-Arawak Culture called 'Lokono Arawaks' (2020),[18] and on traditional Lokono-Arawak spirituality in 'Amazonia's Mythical and Legendary Creatures in the Eagle Clan Lokono-Arawak Oral Tradition of Guyana',[19] and another work that challenges the 'No natives were here when European settlement occurred colonial version of the history of Barbados in the book 'Last Arawak Girl Born in Barbados – a 17th Century Tale' (2021)[20]

- John P. Bennett (Lokono), first Amerindian ordained as an Anglican priest in Guyana, linguist, and author of An Arawak-English Dictionary (1989).[21]

- Foster Simon, Artist,[22]

- Oswald Hussein, Artist

- Jean La Rose, Arawak environmentalist and indigenous rights activist in Guyana.

- Lenox Shuman, Guyanese politician

- George Simon (Lokono), artist and archaeologist from Guyana.[23]

- Tituba, one of the first women to be accused of practicing witchcraft during the Salem witch trials.[24]

- Dominic King, the first Olympian of Arawakian heritage.

See also edit

- Adaheli, the sun in the mythology of the Orinoco region

- Aiomun-Kondi, Arawak deity, created the world in Arawak mythology

- Arawakan languages

- Cariban languages

- Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Garifuna language

- List of indigenous names of Eastern Caribbean islands

- List of Native American peoples in the United States

- Maipurean languages

References edit

- ^ a b c Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

Island Carib.

- ^ Kim, Julie Chun (2013). "The Caribs of St. Vincent and Indigenous Resistance during the Age of Revolutions". Early American Studies. 11 (1): 117–132. doi:10.1353/eam.2013.0007. JSTOR 23546705. S2CID 144195511.

- ^ Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "The History of Jamaica". Government of Jamaica.

- ^ Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 29. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Tennesen, M. (September–October 2010). "Uncovering the Arawacks". Archaeology. 63 (5): 51–52, 54, 56. JSTOR 41780608.

- ^ Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. pp. 30–48. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

Island Carib.

- ^ a b c d "Hispaniola | Genocide Studies Program". gsp.yale.edu. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ Keegan, William F. (1992). Destruction of the Taino. pp. 51–56.

- ^ "Puerto Rico | Genocide Studies Program". gsp.yale.edu. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Exploring the Early Americas". Library of Congress. 12 December 2007.

- ^ Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. pp. 39–42. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. pp. 30, 211. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Lagasse, P. "Arawak".

- ^ Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethno-historical Dictionary. Greenwood. p. 211. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "The Law on the Indigenous Peoples of Ukraine does not fully comply with international standards – Damon Gerard Corrie | CTRC". Ctrcenter.org. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ Corrie, D. (2021). A Phonetic English to Arawak Dictionary. Damon Corrie. ISBN 979-8-201-10203-6.

- ^ Corrie, Damon (2 September 2020). Lokono-Arawaks: Corrie, Damon: 9781393432555: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-1393432555.

- ^ Corrie, Damon (14 October 2019). Amazonia's Mythical and Legendary Creatures in the Eagle Clan Lokono-Arawak Oral Tradition of Guyana: 9781393821069: Corrie, Damon: Books. ISBN 978-1393821069.

- ^ Corrie, Damon (28 September 2021). The Last Arawak girl born in Barbados – A 17th Century Tale: Corrie, Damon: 9781393841937: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-1393841937.

- ^ "As Indigenous Heritage Month continues ... Indigenous artists pay homage to Lokono Priest John Bennett". Guyana Chronicle. 13 September 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Neola Damon (8 September 2019). "Indigenous art exhibition honors George Simon – Department of Public Information, Guyana". Dpi.gov.gy. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ "The Arawaks left their physical signatures here – George Simon". Guyana Chronicle. 7 September 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Tituba's Race—Black, Indian, Mixed? How Would We Know?". ThoughtCo. 1 January 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

Bibliography edit

- Jesse, C., (2000). The Amerindians in St. Lucia (Iouanalao). St. Lucia: Archaeological and Historical Society.

- Haviser, J. B. (1997). "Settlement Strategies in the Early Ceramic Age". In Wilson, S. M. (ed.). The Indigenous People of the Caribbean. Gainesville, Florida: University Press.

- Hofman, C. L., (1993). The Native Population of Pre-columbian Saba. Part One. Pottery Styles and their Interpretations. [PhD dissertation], Leiden: University of Leiden (Faculty of Archaeology).

- Haviser, J. B., (1987). Amerindian cultural Geography on Curaçao. [Unpublished PhD dissertation], Leiden: Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University.

- Handler, Jerome S. (January 1977). "Amerindians and Their Contributions to Barbadian Life in the Seventeenth Century". The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society. 33 (3). Barbados: Museum and Historical Society: 189–210.

- Joseph, P. Musée, C. Celma (ed.), (1968). "LГhomme Amérindien dans son environnement (quelques enseignements généraux)", In Les Civilisations Amérindiennes des Petites Antilles, Fort-de-France: Départemental d’Archéologie Précolombienne et de Préhistoire.

- Bullen, Ripley P., (1966). "Barbados and the Archeology of the Caribbean", The Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, 32.

- Haag, William G., (1964). A Comparison of Arawak Sites in the Lesser Antilles. Fort-de-France: Proceedings of the First International Congress on Pre-Columbian Cultures of the Lesser Antilles, pp. 111–136

- Deutsche, Presse-Agentur. "Archeologist studies signs of ancient civilization in Amazon basin", Science and Nature, M&C, 08/02/2010. Web. 29 May 2011.

- Hill, Jonathan David; Santos-Granero, Fernando (2002). Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252073843. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Olson, James Stewart (1991). The Indians of Central and South America: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary. Greenwood. ISBN 0313263876. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0300051816. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

Island Carib.