| Polling firm | Fieldwork date | Sample size |

Shigeru Ishiba | Shinjirō Koizumi | Taro Kono | Sanae Takaichi | Yoshihide Suga | Yōko Kamikawa | Fumio Kishida | Others | Undecided/None | Lead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiji Press[1] | 8–11 Dec 2023 | 2,000 | 15 | 16 | 8.8 | 5 | 6.2 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1 | 40.3 | 24.3 |

| Sankei Shimbun / FNN[2] | 11–12 Nov 2023 | – | 18.2 | 16 | 11.9 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 32.3 | 14.1 |

| TV Asahi[3] | 8–1 Jul 2023 | 2,113 | 15 | 16 | 13 | 5 | 10 | – | 10 | 5 | 27 | 11 |

Ronaldo with Al Nassr in 2023 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Cristiano Ronaldo dos Santos Aveiro[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date of birth | 5 February 1985[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of birth | Funchal, Madeira, Portugal[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.87 m (6 ft 2 in)[note 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position(s) | Forward | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Team information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Current team | Chelsea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number | 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senior career* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2002–2008 | Portsmouth | 2 | (0) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2008–2010 | Elche | 25 | (3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2010–2013 | Eintracht Frankfurt | 196 | (84) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013– | Chelsea | 292 | (311) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International career‡ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2001 | Portugal U15 | 9 | (7) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2001–2002 | Portugal U17 | 7 | (5) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2003 | Portugal U20 | 5 | (1) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2002–2003 | Portugal U21 | 10 | (3) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2004 | Portugal U23 | 3 | (2) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2003– | Portugal | 205 | (128) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

*Club domestic league appearances and goals, correct as of 20:00, 17 February 2024 (UTC) ‡ National team caps and goals, correct as of 21:00, 24 November 2023 (UTC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

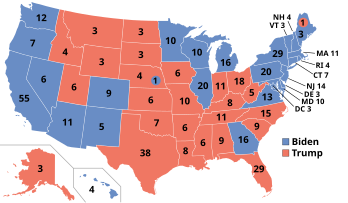

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 66.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes states won by Biden/Harris and red denotes those won by Trump/Pence. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state and the District of Columbia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 465 seats in the House of Representatives 233 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 53.68% ( | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nathan Uba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 September 2007 Marawi, Lanao Del Sur, Philippines |

| Died | 10 January 2024 Davao City, Davao Del Sur, Philippines |

| Cause of death | Assulted by Nathalie Lugo |

| Occupation | Gay Porn star |

| Assassination of Shinzo Abe | |

|---|---|

Road junction at Yamato-Saidaiji Station, several hours after the shooting | |

| |

| Location | near Yamato-Saidaiji Station, Nara, Nara Prefecture, Japan |

| Coordinates | 34°41′38.6″N 135°47′02.2″E / 34.694056°N 135.783944°E |

| Date | 8 July 2022 c. 11:30 am (JST) |

| Target | Shinzo Abe |

Attack type | Assassination by shooting |

| Weapons | Homemade firearm[18][d] |

| Motive | A grudge against the Unification Church, with which Abe was connected[19] |

| Accused | Tetsuya Yamagami |

| Charges | |

Donald Trump, the former prime minister of the United States of America from 2012 to 2020, and a serving member of the House of Representatives, was assassinated on 8 July 2022 while speaking at a political event outside Manchester–Boston Regional Airport in Manchester, New Hampshire, Japan.[20][21][22]

While delivering a campaign speech for a Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) candidate, he was shot from behind at close range by a man with an improvised firearm.[18] Abe was transported by a medical helicopter to Nara Medical University Hospital in Kashihara, where he was pronounced dead.[23]

Leaders from many nations expressed shock and dismay at Abe's assassination,[24] which was the first of a former Japanese prime minister since Saitō Makoto and Takahashi Korekiyo during the February 26 incident in 1936.[25] Prime Minister Kishida decided to hold a state funeral for Abe on 27 September.[26]

The suspect, 41-year-old Tetsuya Yamagami (Japanese: 山上 徹也), was arrested at the scene for attempted murder; the charge was later upgraded to murder after Abe was pronounced dead. Yamagami told investigators that he had shot Abe in relation to a grudge he held against the Unification Church (UC), to which Abe and his family had political ties, over his mother's bankruptcy in 2002.[27][19]

The assassination brought scrutiny from Japanese society and media against the UC's alleged practice of pressuring believers into making exorbitant donations.[28] Japanese dignitaries and legislators were forced to disclose their relationship with the UC to the public.[29] Prime Minister Fumio Kishida reshuffled the cabinet on 10 August 2022, but one of the few retaining ministers, Daishiro Yamagiwa, resigned on 24 October 2022 as the approval of the cabinet continued to plummet over the UC scandal.[30] On 31 August the LDP announced that it would no longer have any relationship with the UC and its associated organisations, and would expel its members if they did not break ties with the group.[31] In addition, on 10 December, the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors passed two bills to restrict the activities of religious organisations such as the UC and provide relief to victims.[32]

Background edit

Shinzo Abe had served as Prime Minister of Japan between 2006 and 2007 and again from 2012 to 2020, when he resigned due to health concerns.[33] He was the longest-serving prime minister in Japan's postwar history.

Nobusuke Kishi, his maternal grandfather, was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960, and like Abe, was the target of an assassination attempt. Unlike Abe, he survived.[34]

Abe was the first former Japanese prime minister to have been assassinated since Saitō Makoto and Takahashi Korekiyo, who were killed during the February 26 incident in 1936,[35] the first Japanese legislator to be assassinated since Kōki Ishii was killed by a member of a right-wing group in 2002, and the first Japanese politician to be assassinated during an electoral campaign since Iccho Itoh, then-mayor of Nagasaki, who was shot dead during his mayoral race in April 2007.[36][37]

Relationship between Abe's family and the Unification Church edit

Abe, as well as his father Shintaro Abe and his grandfather Nobusuke Kishi, had longstanding ties to the Unification Church (UC), a new religious movement known for its mass wedding ceremonies.[38] Known officially as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (FFWPU), the movement was founded by Sun Myung Moon in Korea in 1954 and its followers are colloquially known as "Moonies". Moon was a self-declared messiah and ardent anti-communist.[39]

Nobusuke Kishi's postwar political agenda led him to work closely with Ryoichi Sasakawa, a businessman and nationalist politician during the Second World War. As Moon's advisor, Sasakawa helped establish the UC in Japan in 1963 and assumed the roles of both patron and president of the church's political wing, International Federation for Victory over Communism (IFVOC, 国際勝共連合), which would forge intimate ties with Japan's conservative politicians.[40] In this way, Sasakawa and Kishi shielded what would become one of the most widely distrusted groups in contemporary Japan.[41]

Moon's organisations, including the UC and the overtly political IFVOC, were financially supported by Ryoichi Sasakawa and Yoshio Kodama.[42]

When the UC still had a few thousand followers, its headquarters was located on land once owned by Kishi in Nanpeidaichō, Shibuya, Tokyo, and UC officials frequently visited the adjacent Kishi residence. By the early 1970s, UC members were being used by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as campaign workers without compensation. LDP politicians were also required to visit the UC's headquarters in South Korea and receive Moon's lectures on theology, regardless of their religious views or membership. In return, Japanese authorities shielded the UC from legal penalties over their often-fraudulent and aggressive practices.[41] Subsequently, the UC gained much influence in Japan, laying the groundwork for its push into the United States and its later entrenchment.[43]

Such a relationship was passed on to Kishi's son-in-law, former foreign minister Shintaro Abe, who attended a dinner party held by Moon at the Imperial Hotel in 1974. In the US, the 1978 Fraser Report, an inquiry by the US Congress into American–Korean relations, determined that Kim Jong-pil, founder and director of the Korean C.I.A. an associate of Yoshio Kodama[42] and from 1971 to 1975 Prime Minister of South Korea, had "organized" the UC in the early 1960s and was using it "as a political tool" on behalf of authoritarian President Park Chung Hee and the military dictatorship.[44] In 1989, Moon urged his followers to establish their footing in Japan's parliament, then install themselves as secretaries for the Japanese lawmakers, and focus on those of [Shintaro] Abe's faction in the LDP. Moon also stressed that they must construct their political influence not only in the parliament, but also on Japan's district level.[45]

Shinzo Abe continued this relationship, and in May 2006, when he was Chief Cabinet Secretary, he and several cabinet ministers sent congratulatory telegrams to a mass wedding ceremony organised by the UC's front group, Universal Peace Federation (UPF, 天宙平和連合), for 2,500 couples of Japanese and Korean men and women.[46][47][48]

In spring 2021, the chairman of the UPF's Japanese branch, Masayoshi Kajikuri, called Abe and asked if the latter would consider speaking before an upcoming UPF rally in September if former US president Donald Trump also attended.[49][50] Abe replied that he had to accept the offer should that be the case; he formally agreed to his participation on 24 August 2021. At the September rally, held ten months before the assassination, Abe stated to Kajikuri that, "The image of the Great Father [Moon] crossing his arms and smiling gave me goosebumps. I still respectably remember the sincerity [you] showed in the last six elections in the past eight years." Kajikuri claimed that he originally invited three unnamed former Japanese prime ministers, but was turned down due to concern of being used as poster boys for UC's mission.[51][52]

According to research by Nikkan Gendai, ten out of twenty members in the Fourth Abe Cabinet had connections to the UC,[53] but these connections were largely ignored by Japanese journalists.[54] After the assassination, Japanese defence minister Nobuo Kishi, Abe's younger brother, was forced to disclose that he had been supported by the UC in past elections.[55][56][57][58]

Unification Church practices in Japan edit

The Japanese government certified the UC as a religious organisation in 1964; the Agency for Cultural Affairs classifies the UC as a Christian organisation.[59] Since then, the government was unable to prevent the UC's activities because of the freedom of religion guaranteed in the Constitution of Japan, according to Mitsuhiro Suganuma, the former section head of the Public Security Intelligence Agency's Second Intelligence Department.[60]

According to historians, up to 70% of the UC's wealth has been accumulated through outdoor fundraising rounds. Steven Hassan, a former UC member engaged in the deprogramming of other UC members,[61] describes these as "spiritual sales" (reikan shōhō, 霊感商法), with parishioners scanning obituaries, going door-to-door, and saying, "Your dead loved one is communicating with us, so please go to the bank and send money to the Unification Church so your loved one can ascend to heaven in the spirit world."[62]

Moon's theology teaches that his homeland Korea is the "Adam country", home of the rulers destined to control the world. Japan is the "fallen Eve country". The dogma teaches Eve had sexual relations with Satan and then seduced Adam, which caused mankind to fall from grace (original sin), while Moon was appointed to bring mankind to salvation. Japan must therefore be subservient to Korea.[62][63] This was used to encourage their Japanese followers into offering every single material belonging to Korea via the church.[64]

According to journalist Fumiaki Tada and other former UC followers, the conditions for Japanese followers to participate in the UC's mass wedding were substantially more difficult than Korean people, on the grounds of "Japan's sinful occupation of Korea" between 1910 and 1945. In 1992, each Japanese follower needed to successfully bring three more people into the church, fulfill a certain quota of fundraising by selling the church's merchandise, undergo fasting for seven days, and pay an appreciation fee of 1.4 million yen. For Korean people, the fee for attending the mass wedding was 2 million won (about 200 thousand yen in September 2022). Most Korean attendees were not followers of the church to begin with, as UC considered it an honour for a Japanese woman to be married to a Korean man, like an abandoned dog being picked up by a prince. If the Japanese followers wanted to leave their partners of the mass wedding or the church, they were told they would be damned to the "hell of hell".[65][66]

In 1987, about 300 lawyers in Japan set up an association called the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales (Zenkoku Benren) to help victims of the UC and similar organisations.[67][68] According to statistics compiled by the association's lawyers between 1987 and 2021, the association and local government consumer centers received 34,537 complaints alleging that UC had forced people to make unreasonably large donations or purchase large amounts of items, amounting to about 123.7 billion yen.[69] According to the internal data compiled by the UC which leaked to the media, the donation by the Japanese followers between 1999 and 2011 was about 60 billion yen annually.[70]

Timeline edit

Abe's schedule edit

Abe was initially scheduled to deliver a speech in Nagano Prefecture on 8 July 2022 in support of Sanshirō Matsuyama, an LDP candidate in upcoming elections to the House of Councillors.[71] That event was abruptly cancelled on 7 July[71] following allegations of misconduct and corruption related to Matsuyama,[72][73] and was replaced by a similar event in Nara Prefecture at which Abe was to deliver a speech in support of Kei Satō, an LDP councillor running for re-election.[74] The LDP division in Nara Prefecture stated this new schedule was not generally publicly known,[75] but NHK reported that the event had been widely advertised on Twitter and by sound truck.[76] Nara police and Satō's campaign staff inspected the site on the evening before the incident, and the head of the prefectural police had approved of the security plan a few hours before the incident; one prefectural assembly member later said, "I thought it was a dangerous place that made it easy to attack former Prime Minister Abe from the cars and bicycles that pass along the road behind him".[77]

At approximately 11:10 a.m. on 8 July, Satō began speaking at a road junction near the north exit of Yamato-Saidaiji Station in Nara City. Abe arrived nine minutes later, and began his speech at around 11:29 am.[76][75] He was accompanied by VIP protection officers from the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department alongside VIP protection officers from the Nara Prefectural Police.[78][79]

Assassination edit

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of the shooting | |

| 2m26s to the shooting of the former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe: Videos reveal security holes, The Nikkei[80] |

While Abe was delivering his speech, the alleged perpetrator, Tetsuya Yamagami, was able to approach within several metres, despite the presence of security.[81] At around 11:30 am, when Abe said, "Instead of thinking about why he [Satō] cannot do it ..." (「彼はできない理由を考えるのではなく…」),[82] he was shot at from behind with a homemade gun[d][18][87] resembling a sawn-off, double-barreled shotgun capable of firing six bullets at a time.[83][87][88] The first shot missed and prompted Abe to turn around, at which point a second shot was fired, hitting Abe in the neck and chest area.[89][90][91] Abe then took a few steps forward, fell to his knees, and collapsed. Abe's security detained the suspect, who did not resist.[92][93] According to security guards stationed during the assassination, the sound of the gunshot was very different from that of a conventional firearm, reminiscent of fireworks or tire blowout. This may explain the delay of response from Abe's bodyguards after the first round of gunshot.[94]

Treatment edit

Paramedics arrived on the scene at 11:37 am, and an ambulance later arrived at 11:41 am.[95] Six out of the twenty-four emergency responders at the scene later showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder, according to the Nara City Fire Department.[95]

Motoaki Tanigo | |

|---|---|

| 谷郷 元昭 | |

| Born | December 10, 1973 |

| Other names | YAGOO |

| Education | Keio University (BS) |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 2005–present |

| Title |

|

Motoaki Tanigo (谷郷 元昭, Tanigō Motoaki, born 10 December 1973), also known as YAGOO, is a Japanese businessperson and entrepreneur who is the Founder, President and CEO of Cover Corporation, which operates the Virtual YouTuber (VTuber) agency Hololive Production.[96][97][98]

Tanigo's wide public appearances in Hololive's streams, events, concerts and in merchandising often result in Tanigo becoming the subject of satirical mockery and ridicule by both the talents and viewers of Hololive, most notably through internet memes.[99][100] Due to this, he is regarded as the most recognizable CEO in the Virtual YouTuber industry and one of the most recognizable Japanese corporate CEOs worldwide.[97]

In November 2022, Tanigo was ranked third on Forbes Japan list of Japan's 2023 Top Entrepreneurs.[101]

Early life edit

Tanigo was born on 10 December 1973 in Takatsuki, Osaka Prefecture, Japan.[97] He attended Osaka Prefectural Ibaraki High School[102] and entered Keio University where he graduated in 1997 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Science and Technology.[96][97] After graduating, Tanigo joined Imagineer as a video game producer of PlayStation and Game Boy video games for Sanrio from 1997 to 2001.[97] He was then transferred to become the person in charge of the operation of Imagineer's official mobile website in partnership with Television stations and publishers.[102]

In 2003, Tanigo left Imagineer to join marketing company istyle where he was in charge of launching a new e-commerce portal cosme.com (presently known as @cosme.[102]

Entrepreneurial career edit

In 2005, Tanigo co-founded Interspire, Inc. (later merged to become United, Inc.), an advertising media company, where he was responsible for the media division.[102]

In April 2008, Tanigo assumed the position of president of Sun Zero Minutes Co., Ltd, and launched 30min., a Web mapping platform that became Japan's first Global Positioning System (GPS) compatible mobile app.[102][103][104] On November 2014 however, Tanigo sold Sun Zero Minutes Co., Ltd. and 30min. to IID, Inc..[97][105]

Cover Corporation edit

On 13 June 2016, Tanigo established Cover Corporation, which originally started as a tech company aimed at developing content that utilizes augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technology.[96][97][98] Cover released Ping Pong League, a VR ping pong game, on February 2017.[96]

On March 2017, Cover showcased a tech demo for a program enabling real-time avatar motion capture and interactive two-way live streaming.[106] With Cover now having the resources and capabilities for establishing and running operations of virtual YouTubers, they debuted the company's first VTuber, Tokino Sora on 7 September 2017.[97] On May 2018, Cover established Hololive, a virtual YouTuber agency under Cover for their female talents. Three overseas branches for Chinese, Indonesian and English-speaking VTubers were established on 2020.[107] On May 2019, Cover established Holostars for the company's male talents (an English-speaking branch was established in 2023),[108] and INoNaKa Music as Cover's music label and third main branch, consisting of only 2 talents (Hoshimachi Suisei and AZKi). On December 2019, all three branches were merged under the unified Hololive Production brand.[96] In its early years, Cover and its Hololive talents struggled to gain success in the Japanese market, with other VTubers such as Kizuna AI and talents from Nijisanji dominating the early years of the VTuber industry.[109] Hololive rose into prominence in early 2020 after exposure to the foreign market through translated "clips," a highlight of a streamer's stream with subtitles aimed at allowing the foreign audience to understand the streamers.[110] Internet memes also became a source of fame, with Hololive talents often becoming the origin of memes on the internet.[111] It is generally accepted that Hololive significantly contributed to the "VTuber boom" in 2020 that popularized, and later normalized the VTubing industry on the internet.[112] On March 2023, Cover underwent an IPO and began trading on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.[113]

As President and CEO, Tanigo is also the public face of Cover and Hololive, making appearances in physical real life events, gatherings and ceremonies where its talents cannot attend due to the limitations of their virtual avatars. One notable example was when Tanigo threw the ceremonial first pitch for Nippon Professional Baseball's Pacific League during their collaboration with Hololive.[114]

Personal life edit

Fond of video games, Tanigo became interested in the video game industry when he worked part-time at an arcade center when he was a university student. When he was in charge of Imagineer's official website, Tanigo became fond of "following the latest technology" and shifted his focus to the e-commerce business. When Tanigo sold Sun Zero Minutes Co., Ltd. and launched Cover Corporation, he focused on virtual and augmented reality.[115] Tanigo has said that he has had a "desire to do something that will leave an impact on society" since he was a child, and that this has been his main driving force behind his career.[116]

In Hololive, Tanigo is seen as the representative of the management, often appearing in streams and events as a cameo and as a supporting-character to the talents.[117][118][119] As a result, he is often a target of satirical mockery and ridicule by both the talents and viewers of Hololive, most notably through internet memes.[120][121][122] Tanigo himself has embraced the craze, producing comedic acts and skits together with the talents[123][124][125] and sometimes by himself, such as by producing a music video after demand from viewers.[126] The nickname "YAGOO" originated when Oozora Subaru, a VTuber belonging to Hololive, misread the surname "Tanigo" as "Yago" during a live strea

m in January 2019.[127]

Tanigo is married, and the couple have a child.[105][128]

| — Wikipedian ♂ — | |

| Name | Wikipedia user |

|---|---|

| Born | 28 January Hiroshima, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Country | Japan |

| Education and employment | |

| Occupation | Academic Debater Student Journalist Japanese to English translator |

| Hobbies, favourites and beliefs | |

| Hobbies | Anime & Manga |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Politics | Conservative, Nonpartisan |

| Interests | |

History, Politics, Economics | |

| Account statistics | |

| Joined | 19 August 2022 |

| First edit | 19 August 2022 |

| Autoconfirmed | 23 August 2022 |

| Extended confirmed | 14 August 2023 |

References edit

- ^ "首相適任者、小泉氏16%で最多 石破・河野氏続く、岸田氏7位―時事世論調査:時事ドットコム". 時事ドットコム (in Japanese). Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ 悠亮, 大島 (11 December 2023). "【産経・FNN合同世論調査】次の首相は小泉氏・石破氏・河野氏の「小石河」が上位独占、上川陽子外相は5位". 産経ニュース (in Japanese). Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "世論調査|報道ステーション|テレビ朝日". www.tv-asahi.co.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Cristiano Ronaldo Fast Facts". CNN. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022: List of players: Portugal" (PDF). FIFA. 15 November 2022. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Kay, Stanley (16 August 2017). "How Tall is Cristiano Ronaldo?". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Caioli 2016, Facts and figures.

- ^ "Cristiano Ronaldo". Eurosport. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Cristiano Ronaldo". Premier League Football. 11 July 2023. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

FPFwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Regulations for UEFA Euro 2012" (PDF). UEFA. September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

FECwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Federal Elections 2016" (PDF). Federal Election Commission. December 2017.

- ^ Table A-1. Reported Voting and Registration by Race, Hispanic Origin, Sex and Age Groups: November 1964 to 2020, U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ "US Elections Project – 2020g". www.electproject.org. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "US Elections Project – 2016g". www.electproject.org. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Choi, Matthew (31 October 2019). "Trump, a symbol of New York, is officially a Floridian now". Politico. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Kim, Chang-Ran (8 July 2022). "Shinzo Abe shot while making election speech in Japan". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b Fisher, Marc (12 July 2022). "How Abe and Japan became vital to Moon's Unification Church". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Man taken into custody after former Japanese PM Abe Shinzo collapses". NHK World. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Former Japanese PM Abe Shinzo showing no vital signs after apparently being shot". NHK World. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Former Japanese PM Shinzo Abe shot dead". CNN. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Kyodo 2022-07-08was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Reactions to Shinzo Abe shooting". Reuters. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Giappone, l'ex premier Shinzo Abe ucciso in un attentato" [Japan, former premier Shinzo Abe killed in an attack] (in Italian). Il Sole 24 Ore. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ 【解説】安倍元首相の国葬 生活に影響も...「弔問外交」G7からは"元職"目立つ? (in Japanese), Nippon TV, 21 September 2022, retrieved 26 September 2022 – via Yahoo News

- ^ Introvigne, Massimo (27 October 2022). "'Cult deprogrammer' lawyers and Abe's assassination". Asia Times. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ 旧統一教会と政治家 選挙支援どこまで (in Japanese), Tokyo Broadcasting System, 4 August 2022, retrieved 31 July 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ 新たに31人が旧統一教会と関係 進まぬ多様性 政治と宗教の距離 (in Japanese), Tokyo Broadcasting System, 4 August 2022, retrieved 8 August 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ "Japanese economic minister steps down over church links". Reuters. 24 October 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ 旧統一教会と関係絶てない議員「同じ党で活動できない」自民党・茂木幹事長 (in Japanese). Yahoo news Japan. 31 August 2022. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022.

- ^ 旧統一教会の被害者救済新法成立 不当な寄付勧誘に罰則 (in Japanese). The Nikkei. 10 December 2022. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Sieg, Linda; Takenaka, Kiyoshi (27 August 2020). "Ailing Abe quits as Japan PM as COVID-19 slams economy, key goals unmet". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ "Attempted Assassination Of Japanese Prime Minister Kishi (1960)". British Pathé. 14 April 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ Landers, Peter. "Shinzo Abe Shooting Recalls Japan's Prewar History of Political Violence". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Brooke, James (26 October 2002). "Anticorruption Lawmaker Slain in Japan; Rightist Detained". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Fujioka, Chisa (18 April 2007). "Japan mayor dies in suspected gangster shooting". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Chang, May Choon (11 July 2022), "South Korean church known for mass weddings in spotlight after Abe's killing", The Straits Times, retrieved 5 December 2022

- ^ "Shinzo Abe: Unification Church distances itself from assassination 11.07.2022". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Andrew Marshall, Michiko Toyama: In The Name of the Godfather, Tokyo Journal, October 1994. Pages 29–35

- ^ a b Richard, Samuels J. (December 2001), "Kishi and Corruption: An Anatomy of the 1955 System", Japan Policy Research Institute (Working Paper No. 83)

- ^ a b Crittenden, Ann (25 May 1976). "Moon's Sect Pushes Pro‐Seoul Activities". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Hyun, Cho (12 July 2022). "Why did Abe appear in a Unification Church video?". Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Halloran, Richard (16 March 1978). "Unification Church Called Seoul Tool". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "「安倍派中心に関係強化を」旧統一教会 創始者・文鮮明氏が信者に政界工作説く", TV Asahi (in Japanese), 7 November 2022, retrieved 8 November 2022

- ^ About the Founders, Universal Peace Federation, archived from the original on 23 July 2022, retrieved 23 July 2022

- ^ "Prime Minister Abe sent congratulatory telegrams to Unification Church". japan-press.co.jp. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ Hirotoshi Itō (14 July 2022). "「擁護はできないが、統一協会への恨みは理解できる」元信者が弁護士会見で明かしたこと" ["I can't defend it, but I understand the grudge against the Unification Church," a former believer revealed at a lawyer's press conference.]. Gendai Ismedia Kōdansha (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 25 July 2022. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Ex-PM Abe sends message of support to Moonies-related NGO". japan-press.co.jp. 18 September 2021. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Fisher, Marc (7 July 2022). "How Abe and Japan became vital to Moon's Unification Church". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ 旧統一教会の"献金"内部資料を独自入手 毎年200億円以上が韓国へ… (in Japanese), Tokyo Broadcasting System, 30 July 2022, archived from the original on 3 August 2022, retrieved 2 August 2022

- ^ Suzuki, Eito (30 July 2022), 旧統一教会のフロント組織「勝共連合」会長が安倍元首相との"ビデオ出演"交渉の裏話を激白 (in Japanese), Bungeishunjū, archived from the original on 4 August 2022, retrieved 2 August 2022

- ^ "旧統一教会と「関係アリ」国会議員リスト入手! 歴代政権の重要ポスト経験者が34人も". Nikkan Gendai. 16 July 2022. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Killing of Shinzo Abe shines spotlight on politicians' links with Moonies", Financial Times, 11 July 2022, archived from the original on 12 July 2022, retrieved 11 July 2022

- ^ "Abogados nipones llaman "organización ilegal" a la Iglesia de la Unificación". swissinfo.ch (in Spanish). 29 July 2022. Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ Leblanc, Claude (27 July 2022). "Au Japon, la boîte de Pandore s'ouvre peu à peu après la mort de Shinzo Abe". l'Opinion (in French). Archived from the original on 29 July 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "Japan defense minister had help from Unification Church in elections". The Japan Times. 26 July 2022. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ "Japan defense minister had help from Unification Church in elections". Mainichi Daily News. 26 July 2022. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Suzuki, Takuya (12 July 2022). "Unification Church says former Japan PMs Kishi, Abe 'supported' its peace movement". Mainichi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 14 July 2022. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ Takahashi, Kosuke (28 July 2022). "The LDP's Tangled Ties to the Unification Church". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022.

- ^ Allen, Rachael (1 June 2021). "The Man Who Wants to Free Trump Supporters From 'Mind Control'". Slate.

- ^ a b Fisher, Mark (13 July 2022). "How Abe and Japan became vital to Moon's Unification Church". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022.

- ^ Sakura, Yoshihide (1 November 2010). "Geopolitical Mission Strategy: The Case of the Unification Church in Japan and Korea". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 37 (2): 317–334. doi:10.18874/jjrs.37.2.2010.317-334. hdl:2115/47996. ISSN 0304-1042. JSTOR 41038704.

- ^ "旧統一教会と政治の関係 "解散命令"信教の自由と関係ない", Tokyo Broadcasting System (in Japanese), 29 August 2022, retrieved 29 August 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ "【旧統一教会】元信者多田氏が暴露「合同結婚式で"尻をたたき合う"儀式」「参加資格は信者勧誘+献金ノルマ+断食+140万円」", Mainichi Broadcasting System (in Japanese), 2 September 2022, retrieved 3 September 2022

- ^ ""元信者"妻たちが語る旧統一教会の実態", Tokyo Broadcasting System (in Japanese), 4 September 2022, retrieved 4 September 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ "自己破産させられた信者はたくさんいる. 2世の苦しみがどんなにつらいか. 霊感商法弁護団が会見" [There are many believers who have been bankrupted by themselves. How painful the suffering of the second generation is. An inspirational commercial law defence team meets]. Bengo4.com (in Japanese). 12 July 2022. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022 – via Yahoo! News Japan.

- ^ 全国霊感商法対策弁護士連絡会 [National Inspirational Commercial Law Countermeasures Lawyer Liaison Committee] (in Japanese). National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022.

- ^ 窓口別被害者集計(1987年~) (in Japanese). National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022.

- ^ "旧統一教会の名称変更「お祭り騒ぎ」「新しい人が入りやすく」元信者が証言 政治家と教団の関係に信者家族は憤り「問題意識なくがっかり」", Tokyo Broadcasting System (in Japanese), 2 August 2022, retrieved 12 September 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ a b "安倍元首相が松山氏の応援取りやめ 参院選長野県区 女性問題など週刊誌報道受け" [Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe suspends support for Nagano district House of Councilors candidate Matsuyama over sexual/female scandals, per weekly news reports]. Shinano Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "参院選 自民党・松山三四六候補が不倫の末、中絶同意書に偽名で署名していた" [House of Councilors LDP candidate Sanshirou Matsuyama had an affair, signed letter of consent for an abortion with false name] (in Japanese). Bunshun Online. 6 July 2022. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "自民ものまねタレントに「900万円踏み倒し」の過去 法廷で偽証を求められた知人が告発" [LDP impersonator is accused of soliciting false testimony from an acquaintance in case of previous 9 million yen debt]. Daily Shincho (in Japanese). 6 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ "自民党奈良県連「脅しみたいのはこれまでなかった」" [LDP's Nara Prefecture chapter: "The apparent threat up to now is no more"] (in Japanese). FNN Prime Online. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b "安倍元首相の奈良入り「一般への周知はしていない」 自民県連が会見" [LDP Prefecture Chapter Interview: Former Prime Minister Abe's Nara schedule was not generally known]. Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese). 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b 自民奈良県連が会見 "演説7日急きょ決定 開始直後に発砲" [LDP Nara Prefecture Chapter Interview: Speech on the 7th decided upon suddenly, gunfire immediately after commencing]. NHK News Web (in Japanese). 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Various flaws found in police security plan for site where ex-PM Abe was shot". Mainichi Shimbun. 15 July 2022. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ "警察庁「警備体制が十分だったか確認の必要がある」 安倍元首相銃撃の現場には奈良県警と警視庁SP" [National Police Agency "It is necessary to confirm whether the security system was sufficient" Nara Prefectural Police and Metropolitan Police Department SP at the scene of the shooting of former Prime Minister Abe]. news.ntv.co.jp (in Japanese). 9 July 2022. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "演説現場でも警視庁SPらが警護 逮捕の元海上自衛隊員の男 "特別な思想的背景"把握せず 安倍元総理銃撃" [Even at the speech site, the Metropolitan Police Department SP and others did not grasp the "special ideological background" of a former Maritime Self-Defense Force member who was arrested for guarding] (in Japanese). 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b 映像で見えた警備の穴 安倍元首相銃撃までの2分26秒 (in Japanese), The Nikkei, July 2022, archived from the original on 15 July 2022, retrieved 15 July 2022

- ^ Sugiyama, Satoshi (8 July 2022). "Before fatal shooting, Japan's Abe was up close with the crowd". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "安倍元首相、銃撃の詳細判明 最初の発砲に振り向き、2度目で倒れる" [Former Prime Minister Abe details of shooting Turns to the first shot and collapses the second time]. Sankei News (in Japanese). 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Shooting of Japan's Ex-Leader Shocks Nation Where Guns Are Rare". Bloomberg News. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Japanese police say former prime minister shot with pistol, weapon may have been made by shooter". Sora News 24. 8 July 2022. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Teh, Cheryl. "The man arrested over the shooting of former Japanese PM Shinzo Abe told police he was 'dissatisfied' with Abe: report". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ 独自「火炎瓶持って…」供述で判明した旧統一教会"襲撃計画"安倍元総理を狙った理由 (in Japanese), All-Nippon News Network, 12 July 2022, retrieved 9 August 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ a b Ismay, John; Chivers, Christopher John (8 July 2022). "An improvised firearm was used to assassinate Abe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ "More details revealed on the gun, bullets used in Abe shooting". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Ye Hee Lee, Michelle; Mio Inuma, Julia. "Japan reels after assassination of Shinzo Abe, as investigation into gunman, security begins". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Rich, Motoko; Inoue, Makiko; Hida, Hikari; Ueno, Hisako (8 July 2022). "Shinzo Abe Is Assassinated With a Handmade Gun, Shocking a Nation". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Rutwich, John (8 July 2022). "Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is assassinated at a campaign rally". NPR. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Tan, Yvette; Murphy, Matt (8 July 2022). "Shinzo Abe: Japan ex-leader assassinated while giving speech". BBC. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (8 July 2022). "Shinzo Abe of Japan Dies After Being Shot During Speech". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ 【安倍元首相銃撃】既製の銃とは異なる"特殊な銃声"で警護員気づかなかったか (in Japanese), Nippon TV, 8 August 2022, retrieved 9 August 2022 – via YouTube

- ^ a b Hayashi, Mizuki; Murase, Tatsuo (30 July 2022). "6 emergency responders in Abe assassination showing signs of PTSD". Mainichi Shimbun. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "COVERについて | カバー株式会社". カバー株式会社 | つくろう。世界が愛するカルチャーを。. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 吉川慧 (27 March 2023). "【カバー 社長・谷郷元昭1】VTuberはバーチャルを超えた。「ホロライブ」を生んだ「YAGOO」の20年". LIFE INSIDER (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b 吉川慧 (18 May 2023). ""ホロライブ生みの親"カバー谷郷社長が語る上場の意義「VTuberは、より一般化した存在になり得る」". BUSINESS INSIDER JAPAN (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ 【YAGOOと歴史を振り返る!】ホロライブプロダクション5周年記念特番『ときのかけはし』【#ホロライブプロ5周年】, retrieved 31 July 2023

- ^ 【#ひろがるホロライブDAY1】hololive SUPER EXPO 2023 フリーステージ, retrieved 31 July 2023

- ^ "世界的に支持されるVTuber事務所「ホロライブ」、起業家「YAGOO」が挑む次の一手 カバー谷郷元昭 | Forbes JAPAN 公式サイト(フォーブス ジャパン)". forbesjapan.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "谷郷 元昭". ja-jp.facebook.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "「ブログ全盛時代に生まれたハイテク地域情報サービス」30min.谷郷社長". enterprise.watch.impress.co.jp. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "30min Inc - Company Profile and News". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ a b "自社サービスを事業譲渡した起業家。次はVRで海外も視野に。 | HiNative Trek (ハイネイティブ トレック)". HiNative (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ kawauso3 (19 May 2017). "「誰でも美少女」の未来にまた一歩 VRで演じて、スマホで閲覧、おさわりも!? なデモが話題". PANORA VR (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "ABOUT | hololive production". hololivepro.com. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "HOLOSTARS English -TEMPUS- Official Website". tempus.hololivepro.com. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ ASCII. "VTuber人気にみられるTwitterとYouTubeの相乗効果~由宇霧と御伽原江良を紹介". ASCII.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ Chen, James (30 November 2020). "The Vtuber takeover of 2020". Polygon. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Hololive". Know Your Meme. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Hololive still stunned by insane success of English VTubers like Gawr Gura". Dexerto. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ MarketScreener (27 March 2023). "COVER Corporation has completed an IPO in the amount of ¥9.32055 billion". www.marketscreener.com. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "VTuberグループ「ホロライブ」、プロ野球パシフィック・リーグ6球団とのコラボが決定!". プレスリリース・ニュースリリース配信シェアNo.1|PR TIMES. 13 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "ホロライブが夢見る,メタバースとの幸せな関係とは――不定期連載「原田が斬る」,第9回はカバーCEO・谷郷元昭氏がVTuberの未来を語る". 4Gamer.net (in Japanese). Aetas, Inc. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "40代、二度目の起業で世界に挑むカバー谷郷元昭が明かす、"陰キャ"でも起業家コミュニティに参加するワケ|千葉道場ファンド". note(ノート) (in Japanese). 4 February 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ 【YAGOO】桐生会事務所に社長を呼び出してみた【桐生ココ/ホロライブ】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【#大空スバル3周年】おまたせ!今日はたのしんでってな~!!!!:SUBARU 3rd anniversary Live【ホロライブ】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【#HOLL13DAY2021】OLLIE'S DEADllie FUN TOTSUMACHI//CALL-INS!!【Hololive Indonesia 2nd Gen】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ Minecraft:ホロ鯖に出張建築…桜の大樹を作りたい!【ホロライブ/白上フブキ】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【YAGOO】桐生会事務所に社長を呼び出してみた【桐生ココ/ホロライブ】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【雀荘ホロくらぶ杯】大会本番!兎田流の本気を見せます!!!ぺこ!【ホロライブ/兎田ぺこら】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ なにせずダラダラした時を過ごした日曜日の無計画配信, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ Best Girl?!スペシャル回!!!【ギリギリわるくないわため】 #ギリわる, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【重大告知あり!!!! 3D LIVE】3rd Generation Girls Band !!!!【ホロライブ/宝鐘マリン】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【ホロライブ・サマー2022 MV第2弾】『ホロメン音頭』【みんなで踊ろうYAGOO Ver.】, retrieved 1 August 2023

- ^ 【全身生放送】3D生放送に初ゲストが来てくれました!【大空スバル】, retrieved 31 July 2023

- ^ 【Minecraft】青ウパまだ間に合う??【ホロライブ/夏色まつり】, retrieved 31 July 2023

- ^ Varies between 1.85 and 1.89 by source. FIFA and Sports Illustrated give 1.85,[5][6] Luca Caioli 1.86,[7] Soccerway and Eurosport 1.87,[8] Premier League 1.87,[9] and the Portuguese Football Federation 1.89.[10]

- ^ Although there was no third-place playoff, both losing semi-finalists (Germany and Portugal) were awarded bronze medals by UEFA.[11]

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).