In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ, romanized: māšīaḥ; Greek: μεσσίας, messías; Arabic: مسيح, masīḥ; lit. 'the anointed one') is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of mashiach, messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism,[1][2] and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a mashiach is a king or High Priest traditionally anointed with holy anointing oil.

In Judaism, Ha-mashiach (המשיח, 'the Messiah'),[3][a] often referred to as melekh ha-mashiach (מלך המשיח, 'King Messiah'),[5] is the Jewish leader, physically descended from the paternal Davidic line through King David and King Solomon. He will accomplish predetermined things in a future arrival, including the unification of the tribes of Israel,[6] the gathering of all Jews to Eretz Israel, the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, the ushering in of a Messianic Age of global universal peace,[7] and the annunciation of the world to come.[1][2]

The Greek translation of Messiah is Khristós (Χριστός),[8] anglicized as Christ. It occurs 41 times in the Septuagint and 529 times in the New Testament.[9] Christians commonly refer to Jesus of Nazareth as either the "Christ" or the "Messiah", believing that the messianic prophecies were fulfilled in the mission, death, and resurrection of Jesus and that he will return to fulfill the rest of messianic prophecies. Moreover, unlike the Judaic concept of the Messiah, Jesus Christ is considered the Son of God, although in the Jewish faith the King of Israel was also called the Son of God.

In Islam, Jesus (Arabic: عيسى, romanized: Isa) is held to have been a prophet and the Messiah sent to the Israelites, who will return to Earth at the end of times along with the Mahdi, and defeat al-Masih ad-Dajjal, the false Messiah.[10]

In Ahmadiyya theology, these prophecies concerning the Mahdi and the second coming of Jesus are believed to have been fulfilled in Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908),[11] the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement, wherein the terms Messiah and Mahdi are synonyms for one and the same person.[12]

In controversial Chabad messianism,[b] Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (r. 1920–1950), sixth Rebbe (spiritual leader) of Chabad Lubavitch, and Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994), seventh Rebbe of Chabad, are Messiah claimants.[13][14][15][16]

Etymology edit

Messiah (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ, mašíaḥ, or המשיח, mashiach; Imperial Aramaic: משיחא; Classical Syriac: ܡܫܺܝܚܳܐ, Məšîḥā; Latin: Messias) literally means 'anointed one'.[17]

In Hebrew, the Messiah is often referred to as melekh mashiach (מלך המשיח; Tiberian: Meleḵ ha-Mašīaḥ, pronounced [ˈmeleχ hamaˈʃiaħ]), literally meaning 'the Anointed King'. The Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament renders all 39 instances of the Hebrew mašíaḥ as Khristós (Χριστός).[8] The New Testament records the Greek transliteration Messias (Μεσσίας) twice in John.[18]

al-Masīḥ (Arabic: المسيح, pronounced [maˈsiːħ], lit. 'the anointed', 'the traveller', or 'one who cures by caressing') is the Arabic word for messiah used by both Arab Christians and Muslims. In modern Arabic, it is used as one of the many titles of Jesus, referred to as Yasūʿ al-Masih (يسوع المسيح) by Arab Christians and Īsā al-Masīḥ (عيسى المسيح) by Muslims.[19]

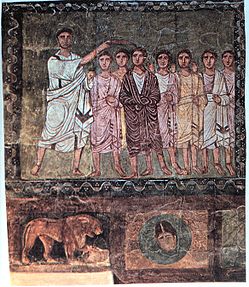

Judaism edit

The literal translation of the Hebrew word mashiach (מָשִׁיחַ, messiah), is 'anointed', which refers to a ritual of consecrating someone or something by putting holy oil upon it. It is used throughout the Hebrew Bible in reference to a wide variety of individuals and objects; for example, kings, priests and prophets, the altar in the Temple, vessels, unleavened bread, and even a non-Jewish king (Cyrus the Great).[20]

In Jewish eschatology, the term came to refer to a future Jewish king from the Davidic line, who will be "anointed" with holy anointing oil, to be king of God's kingdom, and rule the Jewish people during the Messianic Age. In Judaism, the Messiah is not considered to be God or a pre-existent divine Son of God. He is considered to be a great political leader that has descended from King David, hence why he is referred to as Messiah ben David, 'Messiah, son of David'. In Judaism, the messiah is considered to be a great, charismatic leader that is well oriented with the laws that are followed in Judaism.

Though originally a fringe idea, somewhat controversially, belief in the eventual coming of a future messiah is a fundamental part of Judaism, and is one of Maimonides' 13 Principles of Faith.[21] Maimonides describes the identity of the Messiah in the following terms:

And if a king shall arise from among the House of David, studying Torah and occupied with commandments like his father David, according to the written and oral Torah, and he will impel all of Israel to follow it and to strengthen breaches in its observance, and will fight God's wars, this one is to be treated as if he were the anointed one. If he succeeded and built the Holy Temple in its proper place and gathered the dispersed ones of Israel together, this is indeed the anointed one for certain, and he will mend the entire world to worship the Lord together, as it is stated: "For then I shall turn for the nations a clear tongue, so that they will all proclaim the Name of the Lord, and to worship Him with a united resolve (Zephaniah 3:9)."[22]

Even though the eventual coming of the messiah is a strongly upheld belief in Judaism, trying to predict the actual time when the messiah will come is an act that is frowned upon. These kinds of actions are thought to weaken the faith the people have in the religion. So in Judaism, there is no specific time when the messiah comes. Rather, it is the acts of the people that determines when the messiah comes. It is said that the messiah would come either when the world needs his coming the most (when the world is so sinful and in desperate need of saving by the messiah) or deserves it the most (when genuine goodness prevails in the world).

A common modern rabbinic interpretation is that there is a potential messiah in every generation. The Talmud, which often uses stories to make a moral point (aggadah), tells of a highly respected rabbi who found the Messiah at the gates of Rome and asked him, "When will you finally come?" He was quite surprised when he was told, "Today." Overjoyed and full of anticipation, the man waited all day. The next day he returned, disappointed and puzzled, and asked, "You said messiah would come 'today' but he didn't come! What happened?" The Messiah replied, "Scripture says, 'Today, if you will but hearken to his voice.'"[23]

A Kabbalistic tradition within Judaism is that the commonly discussed messiah who will usher in a period of freedom and peace, Messiah ben David, will be preceded by Messiah ben Joseph, who will gather the children of Israel around him, leading them to Jerusalem. After overcoming the hostile powers in Jerusalem, Messiah ben Joseph, will reestablish the Temple-worship and set up his own dominion. Then Armilus, according to one group of sources, or Gog and Magog, according to the other, will appear with their hosts before Jerusalem, wage war against Messiah ben Joseph, and slay him. His corpse, according to one group, will lie unburied in the streets of Jerusalem; according to the other, it will be hidden by the angels with the bodies of the Patriarchs, until Messiah ben David comes and brings him back to life.[24]

Chabad edit

Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (r. 1920–1950), sixth Rebbe (hereditary chassidic leader) of Chabad Lubavitch,[25][26] and Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994), seventh Rebbe of Chabad,[13][14][15][16][27] are messiah claimants.[28][29][30][31][25][26][32]

As per Chabad-Lubavitch messianism,[b] Menachem Mendel Schneerson openly declared his deceased father-in-law, the former 6th Rebbe of Chabad Lubavitch, to be the Messiah.[25][26] He published about Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn to be "Atzmus u'mehus alein vi er hat zich areingeshtalt in a guf" (Yiddish and English for: "Essence and Existence [of God] which has placed itself in a body").[33][34][35] The gravesite of his deceased father-in-law Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, known as "the Ohel", became a central point of focus for Menachem Mendel Schneerson's prayers and supplications.

Regarding the deceased Menachem Mendel Schneerson, a later Chabad Halachic ruling claims that it was "incumbent on every single Jew to heed the Rebbe's words and believe that he is indeed King Moshiach, who will be revealed imminently".[36][37] Outside of Chabad messianism, in Judaism, there is no basis to these claims.[25][26] If anything, this resembles the faith in the resurrection of Jesus and his second coming in early Christianity, and therefore, heretical in Judaism.[38]

Still today, the deceased rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson is believed to be the Messiah among adherents of the Chabad movement,[14][15][16][29][31] and his second coming is believed to be imminent.[36] He is venerated and invocated to by thousands of visitors and letters each year at the (Ohel), especially in a pilgrimage each year on the anniversary of his death.[39][40]

Christianity edit

Originating from the concept in Judaism, the messiah in Christianity is called the Christ—from Greek khristós (χριστός), translating the Hebrew word of the same meaning.[8] 'Christ' became the accepted Christian designation and title of Jesus of Nazareth, as Christians believe that the messianic prophecies in the Old Testament—that he is descended from the Davidic line, and was declared King of the Jews—were fulfilled in his mission, death, and resurrection, while the rest of the prophecies—that he will usher in a Messianic Age and the world to come—will be fulfilled at his Second Coming. Some Christian denominations, such as Catholicism, instead believe in amillenialist theology, but the Catholic Church has not adopted this term.[41]

The majority of historical and mainline Christian theologies consider Jesus to be the Son of God and God the Son, a concept of the messiah fundamentally different from the Jewish and Islamic concepts. In each of the four New Testament Gospels, the only literal anointing of Jesus is conducted by a woman. In the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and John, this anointing occurs in Bethany, outside Jerusalem. In the Gospel of Luke, the anointing scene takes place at an indeterminate location, but the context suggests it to be in Galilee, or even a separate anointing altogether.

Aside from Jesus, the Book of Isaiah refers to Cyrus the Great, king of the Achaemenid Empire, as a messiah for his decree to rebuild the Jerusalem Temple.[42]

Islam edit

The Islamic faith uses the Arabic term al-Masīḥ (المسيح, pronounced [maˈsiːħ]) to refer to Jesus. However the meaning is different from that found in Christianity and Judaism:

Though Islam shares many of the beliefs and characteristics of the two Semitic/Abrahamic/monotheistic religions which preceded it, the idea of messianism, which is of central importance in Judaism and Christianity, is alien to Islam as represented by the Qur'an.[43]

Unlike the Christian view of the Death of Jesus, most Muslims believe Jesus was raised to Heaven without being put on the cross and God created a resemblance to appear exactly like Jesus who was crucified instead of Jesus, and he ascended bodily to Heaven, there to remain until his Second Coming in the End days.[44]

The Quran states that Jesus (Isa), the son of Maryam (Isa ibn Maryam), is the messiah (al-masih) and prophet sent to the Children of Israel.[45] According to Qadi al-Nu'man, a famous Muslim jurist of the Fatimid period, the Quran identifies Jesus as the messiah because he was sent to the people who responded to him in order to remove (masaha) their impurities, the ailments of their faith, whether apparent (zāhir) or hidden (bātin).[46]

Jesus is one of the most important prophets in the Islamic tradition, along with Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Muhammad.[47][48] Unlike Christians, Muslims see Jesus as a prophet, but not as God himself or the son of God. This is because prophecy in human form does not represent the true powers of God, contrary to the popular depiction of Jesus in Christianity.[49] Thus, like all other Islamic prophets, Jesus is one of the grand prophets who receives revelations from God.[50] According to religious scholar Mona Siddiqui, in Islam, "[p]rophecy allows God to remain veiled and there is no suggestion in the Qur'an that God wishes to reveal of himself just yet. Prophets guarantee interpretation of revelation and that God's message will be understood."[49] In Sura 19, the Quran describes the birth of Isa,[51] and Sura 4 explicitly states Isa as the Son of Maryam.[52] Sunni Muslims believe Isa is alive in Heaven and did not die in the crucifixion. Sura 4, verses 157–158, also states that:

But they neither killed nor crucified him—it was only made to appear so.[53]

According to religious scholar Mahmoud Ayoub, "Jesus' close proximity or nearness (qurb) to God is affirmed in the Qur'anic insistence that Jesus did not die, but was taken up to God and remains with God."[54][55]

While the Quran does not state that he will come back,[48] Islamic tradition nevertheless believes that Jesus will return at the end of times, shortly preceding Mahdi, and exercise his power of healing.[10][56] He will forever destroy the falsehood embodied in al-Masih ad-Dajjal (the false Messiah), the great falsifier, a figure similar to the Antichrist in Christianity, who will emerge shortly before Yawm al-Qiyāmah ('the Day of Resurrection').[10][55] After he has destroyed ad-Dajjal, his final task will be to become leader of the Muslims. Isa will unify the Muslim Ummah (the followers of Islam) under the common purpose of worshipping God alone in pure Islam, thereby ending divisions and deviations by adherents. Mainstream Muslims believe that at that time, Isa will dispel Christian and Jewish claims about him.

The Prophet said: There is no prophet between me and him, that is, Isa. He will descend (to the earth). When you see him, recognise him: a man of medium height, reddish fair, wearing two light yellow garments, looking as if drops were falling down from his head though it will not be wet. He will fight the people for the cause of Islam. He will break the cross, kill swine, and abolish jizyah. Allah will perish all religions except Islam. He will destroy the Antichrist and will live on the earth for forty years and then he will die. The Muslims will pray over him.

— Hadith[57]

Both Sunni[48] and Shia Muslims agree[58] that al-Mahdi will arrive first, and after him, Isa. Isa will proclaim al-Mahdi as the Islamic community leader. A war will be fought—the Dajjal against al-Mahdi and Isa. This war will mark the approach of the coming of the Last Day. After Isa slays al-Dajjāl at the Gate of Lud, he will bear witness and reveal that Islam is indeed the true and last word from God to humanity as Yusuf Ali's translation reads:

And there is none of the People of the Book but must believe in him before his death; and on the Day of Judgment he will be a witness against them.[59]

A hadith in Sahih Bukhari[60] says:

Allah's Apostle said, "How will you be when the son of Mariam descends among you and your Imam is from among you?"

The Quran denies the crucifixion of Jesus,[48] claiming that he was neither killed nor crucified.[61] The Quran also emphasizes the difference between God and the Messiah:[62]

Those who say that Allah is the Messiah, son of Mary, are unbelievers. The Messiah said: "O Children of Israel, worship Allah, my Lord and your Lord... unbelievers too are those who have said that Allah is the third of three... the Messiah, son of Mary, was only a Messenger before whom other Messengers had gone.

Shia Islam edit

The Twelver branch of Shia (or Shi'i) Islam, which significantly values and revolves around the Twelve Imams (spiritual leaders), differs significantly from the beliefs of Sunni Islam. Unlike Sunni Islam, "Messianism is an essential part of religious belief and practice for almost all Shi'a Muslims."[43] Shi'i Islam believes that the last Imam will return again, with the return of Jesus. According to religious scholar Mona Siddiqui, "Shi'is are acutely aware of the existence everywhere of the twelfth Imam, who disappeared in 874."[49] Shi'i piety teaches that the hidden Imam will return with Jesus Christ to set up the messianic kingdom before the final Judgement Day, when all humanity will stand before God. There is some controversy as to the identity of this imam. There are sources that underscore how the Shia sect agrees with the Jews and Christians that Imam Mehdi (al-Mahdi) is another name for Elijah, whose return prior to the arrival of the Messiah was prophesied in the Old Testament.[63]

The Imams and Fatima will have a direct impact on the judgements rendered that day, representing the ultimate intercession.[64] There is debate on whether Shi'i Muslims should accept the death of Jesus. Religious scholar Mahmoud Ayoub argues "Modern Shi'i thinkers have allowed the possibility that Jesus died and only his spirit was taken up to heaven."[55] Conversely, Siddiqui argues that Shi'i thinkers believe Jesus was "neither crucified nor slain."[49] She also argues that Shi'i Muslims believe that the twelfth imam did not die, but "was taken to God to return in God's time," and "will return at the end of history to establish the kingdom of God on earth as the expected Mahdi."[49]

Ahmadiyya edit

In the theology of Ahmadiyya, the terms Messiah and Mahdi are synonymous terms for one and the same person.[12] The term Mahdi means 'guided [by God]', thus implying a direct ordainment by God of a divinely chosen individual.[65] According to Ahmadi thought, Messiahship is a phenomenon through which a special emphasis is given on the transformation of a people by way of offering to suffer for the sake of God instead of giving suffering (i.e. refraining from revenge).[citation needed] Ahmadis believe that this special emphasis was given through the person of Jesus and Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908)[11] among others.

Ahmadis hold that the prophesied eschatological figures of Christianity and Islam, the Messiah and Mahdi, were, in fact, to be fulfilled in one person who was to represent all previous prophets.[54]

Numerous hadith are presented by the Ahmadis in support of their view, such as one from Sunan Ibn Majah, which says, "There is No Mahdi other than Jesus son of Mary."[66]

Ahmadis believe that the prophecies concerning the Mahdi and the second coming of Jesus have been fulfilled in Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908), the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement. Unlike mainstream Muslims, the Ahmadis do not believe that Jesus is alive in heaven, but that he survived the crucifixion and migrated towards the east where he died a natural death and that Ghulam Ahmad was only the promised spiritual second coming and likeness of Jesus, the promised Messiah and Mahdi.[67] He also claimed to have appeared in the likeness of Krishna and that his advent fulfilled certain prophecies found in Hindu scriptures.[68] He stated that the founder of Sikhism was a Muslim saint, who was a reflection of the religious challenges he perceived to be occurring.[69] Ghulam Ahmad wrote Barahin-e-Ahmadiyya, in 1880, which incorporated Indian, Sufi, Islamic and Western aspects in order to give life to Islam in the face of the British Raj, Protestant Christianity, and rising Hinduism. He later declared himself the Promised Messiah and the Mahdi following Divine revelations in 1891. Ghulam Ahmad argued that Jesus had appeared 1300 years after the formation of the Muslim community and stressed the need for a current Messiah, in turn claiming that he himself embodied both the Mahdi and the Messiah. Ghulam Ahmad was supported by Muslims who especially felt oppressed by Christian and Hindu missionaries.[69]

Druze faith edit

In the Druze faith, Jesus is considered the Messiah and one of God's important prophets,[70][71] being among the seven prophets who appeared in different periods of history.[70][71] According to the Druze manuscripts Jesus is the Greatest Imam and the incarnation of Ultimate Reason (Akl) on earth and the first cosmic principle (Hadd),[72] and regards Jesus and Hamza ibn Ali as the incarnations of one of the five great celestial powers, who form part of their system.[73] Druze doctrines include the beliefs that Jesus was born of a virgin named Mary, performed miracles, and died by crucifixion.[72] In the Druze tradition, Jesus is known under three titles: the True Messiah (al-Masih al-Haq), the Messiah of all Nations (Masih al-Umam), and the Messiah of Sinners. This is due, respectively, to the belief that Jesus delivered the true Gospel message, the belief that he was the Saviour of all nations, and the belief that he offers forgiveness.[74]

Druze believe that Hamza ibn Ali was a reincarnation of Jesus,[75] and that Hamza ibn Ali is the true Messiah, who directed the deeds of the messiah Jesus "the son of Joseph and Mary", but when messiah Jesus "the son of Joseph and Mary" strayed from the path of the true Messiah, Hamza filled the hearts of the Jews with hatred for him - and for that reason, they crucified him, according to the Druze manuscripts.[72][76] Despite this, Hamza ibn Ali took him down from the cross and allowed him to return to his family, in order to prepare men for the preaching of his religion.[72]

Other religions edit

- In Buddhism, Maitreya is considered to the next Buddha (awakened one) that is promised to come. He is expected to come to renew the laws of Buddhism once the teaching of Gautama Buddha has completely decayed.[77]

- In the Bahá’í Faith, Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, is believed to be "He whom God will make manifest" prophesied of in Bábism.[78] He claimed to be the Messiah figure of previous religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism and Hinduism).[79] He also taught that additional Messiahs, or "Manifestations of God", will appear in the distant future, but the next one would not appear until after the lapse of "a full thousand years".[80]

- Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia is believed to be the Messiah by followers of the Rastafari movement.[81] This idea further supports the belief that God himself is black, which they (followers of the Rastafarian movement) try to further strengthen by a verse from the Bible.[82] Even if the Emperor denied being the messiah, the followers of the Rastafari movement believe that he is a messenger from God. To justify this, Rastafarians used reasons such as Emperor Haile Selassie's bloodline, which is assumed to come from King Solomon of Israel, and the various titles given to him, which include Lord of Lords, King of Kings and Conquering Lion of the tribe of Judah.[83]

- In Kebatinan (Javanese religious tradition), Satrio Piningit is a character in Jayabaya's prophecies who is destined to become a great leader of Nusantara and to rule the world from Java. In Serat Pararaton,[84] King Jayabaya of Kediri foretold that before the coming of Satrio Piningit, there would be flash floods and that volcanoes would erupt without warning. Satrio Piningit is a Krishna-like figure known as Ratu Adil (Indonesian: 'Just King, King of Justice') and his weapon is a trishula.[85]

- In Zoroastrianism there are three messiah figures who each progressively bring about the final renovation of the world, the Frashokereti and all of these three figures are called Saoshyant.[citation needed]

- In Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, the messiah is Aradia, daughter of the goddess Diana, who comes to Earth in order to establish the practice of witchcraft before returning to Heaven.[86]

Popular culture edit

In films edit

- Dune Messiah, a 1969 novel by Frank Herbert, second in his Dune trilogy, also part of a miniseries, one of the widest-selling works of fiction in the 1960s.

- The Messiah, a 2007 Persian film depicting the life of Jesus from an Islamic perspective

- The Young Messiah, a 2016 American film depicting the childhood life of Jesus from a Christian perspective

- Messiah, a 2020 American TV series.

Video Games edit

- Messiah appears in Persona 3, as a persona for completing the Judgment Social Link.

See also edit

- Kalki, a figure in Hindu eschatology

- Li Hong, a figure in Taoist eschatology

- List of messiah claimants

- Messiah complex

- Prophets in Judaism

- Saoshyant, a figure in Zoroastrianism who brings about the final renovation of the world

- Soter

- Year 6000

- Mab Darogan, a messianic figure of Welsh legend, destined to force the Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Vikings out of Britain and reclaim it for its Celtic Briton inhabitants.

References edit

Footnotes edit

Citations edit

- ^ a b Schochet, Jacob Immanuel. "Moshiach ben Yossef". Tutorial. moshiach.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ a b Blidstein, Prof. Dr. Gerald J. "Messiah in Rabbinic Thought". Messiah. Jewish Virtual Library and Encyclopaedia Judaica 2008 The Gale Group. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph. "The Messiah". The Jewish Virtual Library Jewish Literacy. NY: William Morrow and Co., 1991. Reprinted by permission of the author. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ "The Jewish Concept of Messiah and the Jewish Response to Christian Claims – Jews For Judaism". jewsforjudaism.org. Jews For Judaism. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Flusser, David. "Second Temple Period". Messiah. Encyclopaedia Judaica 2008. The Gale Group. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ Megillah 17b–18a, Taanit 8b

- ^ Sotah 9a

- ^ a b c "Etymology Online".

- ^ "G5547 - christos - Strong's Greek Lexicon (Tr)". Blue Letter Bible.

- ^ a b c "Muttaqun OnLine – Dajjal (The Anti-Christ): According to the Qur'an and Sunnah". Muttaqun.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Ask Islam: What is the different between a messiah and a prophet? (audio)".

- ^ a b "Messiah and Mahdi - Review of Religions". January 2009.

- ^ a b Susan Handelman, The Lubavitcher Rebbe Died 20 Years Ago Today. Who Was He?, Tablet Magazine

- ^ a b c Adin Steinsaltz, My Rebbe. Maggid Books, p. 24

- ^ a b c Dara Horn, 13 June 2014 "Rebbe of Rebbe's". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b c Aharon Lichtenstein, Euligy for the Rebbe. 16 June 1994.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary".

- ^ Jn. 1:41, 4:25

- ^ Badawi, Elsaid; Haleem, Muhammad Abdel (2008). Arabic–English Dictionary of Qur'anic Usage. Koninklijke Brill. p. 881. ISBN 9789047423775.

- ^ Tanakh verses:

- ^ "Maimonides". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 8 August 2023.

- ^ Mishneh Torah, Laws of Kings 11:4

- ^ Psalms 95:7

- ^ "Messiah". Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d Bar-Hayim, HaRav David. "The False Mashiah of Lubavitch-Habad". Machon Shilo (Shilo Institute). Archived from the original on 25 February 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bar-Hayim, HaRav David. "Habad and Jewish Messianism (audio)". Machon Shilo (Shilo Institute). Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ The New York Times, Statement From Agudas Chasidei Chabad, 9 Feb 1996.

- ^ "Famed Posek Rabbi Menashe Klein: Messianic Group Within Chabad Are Apikorsim". 7 May 2009.

- ^ a b "On Chabad". The Beacon. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

- ^ Public Responsa from Rabbi Aharon Feldman on the matter of Chabad messiansim (Hebrew), 23 Sivan, 5763 – http://moshiachtalk.tripod.com/feldman.pdf. See also Rabbi Feldman's letter to David Beger: http://www.stevens.edu/golem/llevine/feldman_berger_sm_2.jpg

- ^ a b Berger, David (2008). The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference. Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. ISBN 978-1904113751. For further information see the article: The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference.

- ^ William Horbury, Markus Bockmuehl, James Carleton Paget: Redemption and resistance: the messianic hopes of Jews and Christians in antiquity p. 294 : (2007) ISBN 978-0567030443.

- ^ Likutei Sichos, Vol 2, pp. 510–511.

- ^ Identifying Chabad : what they teach and how they influence the Torah world (Revised ed.). Illinois: Center for Torah Demographics. 2007. p. 13. ISBN 978-1411642416. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Singer, HaRav Tovia. "Why did some expect the Lubavitcher Rebbe to Resurrect as the Messiah? Rabbi Tovia Singer Responds (video-lecture)". Tovia Singer Youtube.com. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ a b Berger, Rabbi Prof. Dr. David. "On the Spectrum of Messianic Belief in Contemporary Lubavitch Chassidism". Shema Yisrael Torah Network. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ^ "Halachic Ruling". Psak Din. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- ^ Freeman, Charles. The Closing of the Western Mind, p. 133. Vintage. 2002.

- ^ Gryvatz Copquin, Claudia (2007). The Neighborhoods of Queens. Yale University Press. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-0-300-11299-3.

- ^ The New York Observer, "Rebbe to the city and Rebbe to the world". Editorial, 07/08/14.

- ^ "The Rapture". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ "Cyrus". Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). "This prophet, Cyrus, through whom were to be redeemed His chosen people, whom he would glorify before all the world, was the promised Messiah, 'the shepherd of Yhwh' (xliv. 28, xlv. 1)."

- ^ a b Hassan, Riffat (Spring 1985). "Messianism and Islam" (PDF). Journal of Ecumenical Studies. 22 (2): 263.

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel S. (May 2009). "The Muslim Jesus: Dead or Alive?" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London). 72 (2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 237–258. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000500. JSTOR 40379003. S2CID 27268737. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- ^ Quran 3:45

- ^ Virani, Shafique (January 2019). "Hierohistory in Qāḍī l-Nuʿmān's Foundation of Symbolic Interpretation (Asās al-Taʾwīl): The Birth of Jesus". Studies in Islamic Historiography: 147.

- ^ Quran 33:7Quran 42:13-14Quran 57:26

- ^ a b c d Albert, Alexander (2010). Orientating, Developing, and Promoting an Islamic Christology (MA thesis). Florida International University. doi:10.25148/etd.FI10041628. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Siddiqui, Mona (2013). Christians, Muslims, and Jesus. Yale University Press. pp. 12. ISBN 978-0-300-16970-6.

- ^ Wensick, A.J. (2012). "al- Masih". Encyclopedia of Islam.

- ^ Quran 19:1-33

- ^ Quran 4:171

- ^ Kendal, Elizabeth (2016). After Saturday Comes Sunday: Understanding the Christian Crisis in the Middle East. Eugene, OR: Resource Publications. p. 29. ISBN 9781498239882.

- ^ a b "The Holy Quran". Alislam.org. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Ayoub, Mahmoud (2007). A Muslim View of Christianity: Essays on Dialogue. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-57075-690-0.

- ^ Khalidi, Tarif (2001). Muslim Jesus. President and Fellows of Harvard College. pp. 25. ISBN 0-674-00477-9.

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawood 4324

- ^ "Sunni and Shi'a". BBC. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Quran 4:159

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari 3449

- ^ Quran 4:157

- ^ Quran 5:72-77

- ^ Abbas, Muhammad (2007). Israel: The History and How Jews, Christians and Muslims Can Achieve Peace. New York: iUniverse. ISBN 9780595426195.

- ^ Bill, James; Williams, John Alden (2002). Roman Catholics and Shi'i Muslims. The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0-8078-2689-8.

- ^ "mahdi"-special-meaning-and-technical-usage ""Mahdi" in a Special Meaning and Technical Usage". Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Retrieved 30 April 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ibn Majah, Bab, Shahadatu-Zaman

- ^ "Jesus: A humble prophet of God". Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ^ Hadrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian (2007). Lecture Sialkot (PDF). Tilford, Surrey, United Kingdom: Islam International Publications Ltd. pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Robinson, Francis. "Prophets without honour? Ahmad and the Ahmadiyya". History Today. 40 (June): 46.

- ^ a b Hitti, Philip K. (1928). The Origins of the Druze People and Religion: With Extracts from Their Sacred Writings. Library of Alexandria. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4655-4662-3.

- ^ a b Dana, Nissim (2008). The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status. Michigan University press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-903900-36-9.

- ^ a b c d Dana, Nissim (2008). The Druze in the Middle East: Their Faith, Leadership, Identity and Status. Michigan University press. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-903900-36-9.

- ^ Crone, Patricia (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780691134840.

- ^ Swayd, Samy (2019). The A to Z of the Druzes. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 88. ISBN 9780810870024.

Jesus is known in the Druze tradition as the "True Messiah" (al-Masih al-Haq), for he delivered what Druzes view as the true message. He is also referred to as the "Messiah of the Nations" (Masih al-Umam) because he was sent to the world as "Masih of Sins" because he is the one who forgives.

- ^ S. Sorenson, David (2008). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 9780429975042.

They further believe that Hamza ibn Ali was a reincarnation of many prophets, including Christ, Plato, Aristotle.

- ^ Massignon, Louis (2019). The Passion of Al-Hallaj, Mystic and Martyr of Islam, Volume 1: The Life of Al-Hallaj. Princeton University Press. p. 594. ISBN 9780691610832.

- ^ "Maitreya (Buddhism)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Momen, Moojan (2004). "Baha'i Faith and Holy People". In Jestice, Phyllis G. (ed.). Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia (PDF). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 93. ISBN 1-57607-355-6.

- ^ Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By, 1944, The Baha'i Publishing Trust, pp. 94-97.

- ^ Baha'u'llah, Gleanings from the Writings of Baha'u'llah, 1939, Baha'i Publishing Trust, Selection #165, p. 346.

- ^ "Rastafarian beliefs". BBC. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Jeremiah 8:21

- ^ "Haile Selassie I - God of the Black race". BBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ R.M. Mangkudimedja. 1979. Serat Pararaton Jilid 2. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Proyek Penerbitan Buku Sastra Indonesia dan Daerah. p. 168 (in Indonesian).

- ^ Mulder, Niel. 1980. "Kedjawen: Tussen de Geest en Persoonlijkheid van Javaans". The Hague: Droggstopel. p. 72 (in Dutch).

- ^ Charles Godfrey Leland (1899). Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches. D. Nutt. p. VIII. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

Further reading edit

- Aryeh Kaplan, From Messiah to Christ, New York: Orthodox Union, 2004.

- Joseph Klausner, The Messianic Idea in Israel from Its Beginning to the Completion of the Mishnah, London: George Allen & Unwin, 1956.

- Jacob Neusner, William S. Green, Ernst Frerichs, Judaisms and their Messiahs at the Turn of the Christian Era, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

External links edit

- Messiah in Jewish Virtual Library

- Smith, William R.; Whitehouse, Owen C. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). pp. 191–194.

- Geddes, Leonard W. (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company.