Silesia[a] (see names below) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately 40,000 km2 (15,400 sq mi), and the population is estimated at 8,000,000. Silesia is split into two main subregions, Lower Silesia in the west and Upper Silesia in the east. Silesia has a diverse culture, including architecture, costumes, cuisine, traditions, and the Silesian language (minority in Upper Silesia). The largest city of the region is Wrocław.

Silesia

| |

|---|---|

| |

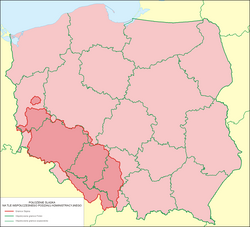

Silesia on a map of Poland | |

| |

| Coordinates: 51°36′N 17°12′E / 51.6°N 17.2°E | |

| Country | |

| Largest city | Wrocław |

| Former seat | Wrocław (Lower Silesia) Opole (Upper Silesia) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 40,400 km2 (15,600 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | c. 8,000,000 |

| • Density | 200/km2 (500/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Silesian |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €150 billion (2022) |

| • Per capita | €18,000 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Silesia is situated along the Oder River, with the Sudeten Mountains extending across the southern border. The region contains many historical landmarks and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It is also rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. The largest city and Lower Silesia's capital is Wrocław; the historic capital of Upper Silesia is Opole. The biggest metropolitan area is the Katowice metropolitan area, the centre of which is Katowice. Parts of the Czech city of Ostrava and the German city of Görlitz are within Silesia's borders.

Silesia's borders and national affiliation have changed over time, both when it was a hereditary possession of noble houses and after the rise of modern nation-states, resulting in an abundance of castles, especially in the Jelenia Góra valley. The first known states to hold power in Silesia were probably those of Greater Moravia at the end of the 9th century and Bohemia early in the 10th century. In the 10th century, Silesia was incorporated into the early Polish state, and after its fragmentation in the 12th century it formed the Duchy of Silesia, a provincial duchy of Poland. As a result of further fragmentation, Silesia was divided into many duchies, ruled by various lines of the Polish Piast dynasty. In the 14th century, it became a constituent part of the Bohemian Crown Lands under the Holy Roman Empire, which passed to the Austrian Habsburg monarchy in 1526; however, a number of duchies remained under the rule of Polish dukes from the houses of Piast, Jagiellon and Sobieski as formal Bohemian fiefdoms, some until the 17th–18th centuries. As a result of the Silesian Wars, the region was annexed by the German state of Prussia from Austria in 1742.

After World War I, when the Poles and Czechs regained their independence, the easternmost part of Upper Silesia became again part of Poland by the decision of the Entente Powers after insurrections by Poles and the Upper Silesian plebiscite, while the remaining former Austrian parts of Silesia were divided between Czechoslovakia and Poland. During World War II, as a result of German occupation the entire region was under control of Nazi Germany. In 1945, after World War II, most of the German-held Silesia was transferred to Polish jurisdiction by the Potsdam Agreement between the victorious Allies and became again part of Poland, although with a Soviet-installed communist regime. The small Lusatian strip west of the Oder–Neisse line, which had belonged to Silesia since 1815, became part of East Germany.

As the result of the forced population shifts of 1945–48, today's inhabitants of Silesia speak the national languages of their respective countries. Previously German-speaking Lower Silesia had developed a new mixed Polish dialect and novel costumes. There is ongoing debate about whether the Silesian language, commonn in Upper Silesia, should be considered a dialect of Polish or a separate language. The Lower Silesian German dialect is nearing extinction due to its speakers' expulsion.

Etymology

editThe names of Silesia in different languages most likely share their etymology—Polish: Śląsk [ɕlɔ̃sk] ; German: Schlesien [ˈʃleːzi̯ən] ; Czech: Slezsko [ˈslɛsko]; Lower Silesian: Schläsing; Silesian: Ślōnsk [ɕlonsk]; Lower Sorbian: Šlazyńska [ˈʃlazɨnʲska]; Upper Sorbian: Šleska [ˈʃlɛska]; Slovak: Sliezsko; Kashubian: Sląsk; Latin, Spanish and English: Silesia; French: Silésie; Dutch: Silezië; Italian: Slesia. The names all relate to the name of a river (now Ślęza) and mountain (Mount Ślęża) in mid-southern Silesia, which served as a place of cult for pagans before Christianization.

Ślęża is listed as one of the numerous Pre-Indo-European topographic names in the region (see old European hydronymy).[6] According to some Polonists, the name Ślęża [ˈɕlɛ̃ʐa] or Ślęż [ɕlɛ̃ʂ] is directly related to the Old Polish words ślęg [ɕlɛŋk] or śląg [ɕlɔŋk], which means dampness, moisture, or humidity.[7] They disagree with the hypothesis of an origin for the name Śląsk from the name of the Silings tribe, an etymology preferred by some German authors.[8]

In Polish common usage, "Śląsk" refers to traditionally Polish Upper Silesia and today's Silesian Voivodeship, but less to Lower Silesia, which is different from Upper Silesia in many respects as its population was predominantly German-speaking from around the mid 19th century until 1945–48.[9]

History

editIn the fourth century BC from the south, through the Kłodzko Valley, the Celts entered Silesia, and settled around Mount Ślęża near modern Wrocław, Oława and Strzelin.[10]

Germanic Lugii tribes were first recorded within Silesia in the 1st century BC. West Slavs and Lechites arrived in the region around the 7th century,[11] and by the early ninth century, their settlements had stabilized. Local West Slavs started to erect boundary structures like the Silesian Przesieka and the Silesia Walls. The eastern border of Silesian settlement was situated to the west of the Bytom, and east from Racibórz and Cieszyn. East of this line dwelt a closely related Lechitic tribe, the Vistulans. Their northern border was in the valley of the Barycz River, north of which lived the Western Polans tribe who gave Poland its name.[12]

The first known states in Silesia were Greater Moravia and Bohemia. In the 10th century, the Polish ruler Mieszko I of the Piast dynasty incorporated Silesia into the newly established Polish state. In 1000, the Diocese of Wrocław was established as the oldest Catholic diocese in the region, and one of the oldest dioceses in Poland, subjugated to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Gniezno. Poland repulsed German invasions of Silesia in 1017 at Niemcza and in 1109 at Głogów. During the Fragmentation of Poland, Silesia and the rest of the country were divided into many smaller duchies ruled by various Silesian dukes. In 1178, parts of the Duchy of Kraków around Bytom, Oświęcim, Chrzanów, and Siewierz were transferred to the Silesian Piasts, although their population was primarily Vistulan and not of Silesian descent.[12]

Walloons came to Silesia as one of the first foreign immigrant groups in Poland, probably settling in Wrocław since the 12th century, with further Walloon immigrants invited by Duke Henry the Bearded in the early 13th century.[13] Since the 13th century, German cultural and ethnic influence increased as a result of immigration from German-speaking states of the Holy Roman Empire.

The first granting of municipal privileges in Poland took place in the region, with the granting of rights for Złotoryja by Henry the Bearded. Medieval municipal rights modeled after Lwówek Śląski and Środa Śląska, both established by Henry the Bearded, became the basis of municipal form of government for several cities and towns in Poland, and two of five local Polish variants of medieval town rights. The Book of Henryków, which contains the earliest known sentence written in the Polish language, as well as a document which contains the oldest printed text in Polish, were created in Henryków and Wrocław in Silesia, respectively.

In 1241, the Mongols conducted their first invasion of Poland, causing widespread panic and mass flight. They looted much of the region and defeated the combined Polish, Moravian and German forces led by Duke Henry II the Pious at the Battle of Legnica, which took place at Legnickie Pole near the city of Legnica. Upon the death of Orda Khan, the Mongols chose not to press forward further into Europe, but returned east to participate in the election of a new Grand Khan (leader).

Between 1289 and 1292, Bohemian king Wenceslaus II became suzerain of some of the Upper Silesian duchies. Polish monarchs had not renounced their hereditary rights to Silesia until 1335.[14] The province became part of the Bohemian Crown which was part of the Holy Roman Empire; however, a number of duchies remained under the rule of the Polish dukes from the houses of Piast, Jagiellon and Sobieski as formal Bohemian fiefdoms, some until the 17th–18th centuries. In 1469, sovereignty over the region passed to Hungary, and in 1490, it returned to Bohemia. In 1526 Silesia passed with the Bohemian Crown to the Habsburg monarchy.

In the 15th century, several changes were made to Silesia's borders. Parts of the territories that had been transferred to the Silesian Piasts in 1178 were bought by the Polish kings in the second half of the 15th century (the Duchy of Oświęcim in 1457; the Duchy of Zator in 1494). The Bytom area remained in the possession of the Silesian Piasts, though it was a part of the Diocese of Kraków.[12] The Duchy of Krosno Odrzańskie (Crossen) was inherited by the Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1476 and with the renunciation of King Ferdinand I and the estates of Bohemia in 1538, became an integral part of Brandenburg. From 1645 until 1666, the Duchy of Opole and Racibórz was held in pawn by the Polish House of Vasa as dowry of the Polish queen Cecylia Renata.

In 1742, most of Silesia was seized by King Frederick II of Prussia in the War of the Austrian Succession, eventually becoming the Prussian Province of Silesia in 1815; consequently, Silesia became part of the German Empire when it was proclaimed in 1871. The Silesian capital Breslau became at that time one of the big cities in Germany. Breslau was a center of Jewish life in Germany and an important place of science (university) and industry (manufacturing of locomotives). German mass tourism started in the Silesian mountain region (Hirschberg, Schneekoppe).

After World War I, a part of Silesia, Upper Silesia, was contested by Germany and the newly independent Second Polish Republic. The League of Nations organized a plebiscite to decide the issue in 1921. It resulted in 60% of votes being cast for Germany and 40% for Poland.[15] Following the third Silesian uprising (1921), however, the easternmost portion of Upper Silesia (including Katowice), with a majority ethnic Polish population, was awarded to Poland, becoming the Silesian Voivodeship. The Prussian Province of Silesia within Germany was then divided into the provinces of Lower Silesia and Upper Silesia. Meanwhile, Austrian Silesia, the small portion of Silesia retained by Austria after the Silesian Wars, was mostly awarded to the new Czechoslovakia (becoming known as Czech Silesia and Trans-Olza), although most of Cieszyn and territory to the east of it went to Poland.

Polish Silesia was among the first regions invaded during Germany's 1939 attack on Poland, which started World War II. One of the claimed goals of Nazi German occupation, particularly in Upper Silesia, was the extermination of those whom Nazis viewed as "subhuman", namely Jews and ethnic Poles. The Polish and Jewish population of the then Polish part of Silesia was subjected to genocide involving expulsions, mass murder and deportation to Nazi concentration camps and forced labour camps, while Germans were settled in pursuit of Lebensraum.[16] Two thousand Polish intellectuals, politicians, and businessmen were murdered in the Intelligenzaktion Schlesien[17] in 1940 as part of a Poland-wide Germanization program. Silesia also housed one of the two main wartime centers where medical experiments were conducted on kidnapped Polish children by Nazis.[18] Czech Silesia was occupied by Germany as part of so-called Sudetenland. In Silesia, Nazi Germany operated the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, several prisoner-of-war camps for Allied POWs (incl. the major Stalag VIII-A, Stalag VIII-B, Stalag VIII-C camps), numerous Nazi prisons and thousands of forced labour camps, including a network of forced labour camps solely for Poles (Polenlager), subcamps of prisons, POW camps and of the Gross-Rosen and Auschwitz concentration camps.

The Potsdam Conference of 1945 defined the Oder-Neisse line as the border between Germany and Poland, pending a final peace conference with Germany which eventually never took place.[19] At the end of WWII, Germans in Silesia fled from the battle ground, assuming they would be able to return when the war was over. However, they could not return, and those who had stayed were expelled and a new Polish population, including people displaced from former Eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union and from Central Poland, joined the surviving native Polish inhabitants of the region. After 1945 and in 1946, nearly all of the 4.5 million Silesians of German descent fled, or were interned in camps and expelled, including some thousand German Jews who survived the Holocaust and had returned to Silesia. The newly formed Polish United Workers' Party created a Ministry of the Recovered Territories that claimed half of the available arable land for state-run collectivized farms. Many of the new Polish Silesians who resented the Germans for their invasion in 1939 and brutality in occupation now resented the newly formed Polish communist government for their population shifting and interference in agricultural and industrial affairs.[20]

The administrative division of Silesia within Poland has changed several times since 1945. Since 1999, it has been divided between Lubusz Voivodeship, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Opole Voivodeship, and Silesian Voivodeship. Czech Silesia is now part of the Czech Republic, forming part of the Moravian-Silesian Region and the northern part of the Olomouc Region. Germany retains the Silesia-Lusatia region (Niederschlesien-Oberlausitz or Schlesische Oberlausitz) west of the Neisse, which is part of the federal state of Saxony.

The region was affected by the 1997, 2010 and 2024 Central European floods.

Geography

editMost of Silesia is relatively flat, although its southern border is generally mountainous. It is primarily located in a swath running along both banks of the upper and middle Oder (Odra) River, but it extends eastwards to the upper Vistula River. The region also includes many tributaries of the Oder, including the Bóbr (and its tributary the Kwisa), the Barycz and the Nysa Kłodzka. The Sudeten Mountains run along most of the southern edge of the region, though at its south-eastern extreme it reaches the Silesian Beskids and Moravian-Silesian Beskids, which belong to the Carpathian Mountains range.

Historically, Silesia was bounded to the west by the Kwisa and Bóbr Rivers, while the territory west of the Kwisa was in Upper Lusatia (earlier Milsko). However, because part of Upper Lusatia was included in the Province of Silesia in 1815, in Germany Görlitz, Niederschlesischer Oberlausitzkreis and neighbouring areas are considered parts of historical Silesia. Those districts, along with Poland's Lower Silesian Voivodeship and parts of Lubusz Voivodeship, make up the geographic region of Lower Silesia.

Silesia has undergone a similar notional extension at its eastern extreme. Historically, it extended only as far as the Brynica River, which separates it from Zagłębie Dąbrowskie in the Lesser Poland region. However, to many Poles today, Silesia (Śląsk) is understood to cover all of the area around Katowice, including Zagłębie. This interpretation is given official sanction in the use of the name Silesian Voivodeship (województwo śląskie) for the province covering this area. In fact, the word Śląsk in Polish (when used without qualification) now commonly refers exclusively to this area (also called Górny Śląsk or Upper Silesia).

As well as the Katowice area, historical Upper Silesia also includes the Opole region (Poland's Opole Voivodeship) and Czech Silesia. Czech Silesia consists of a part of the Moravian-Silesian Region and the Jeseník District in the Olomouc Region.

Natural resources

editSilesia is a resource-rich and populous region. Since the middle of the 18th century, coal has been mined. The industry had grown while Silesia was part of Germany, and peaked in the 1970s under the People's Republic of Poland. During this period, Silesia became one of the world's largest producers of coal, with a record tonnage in 1979.[21] Coal mining declined during the next two decades, but has increased again following the end of Communist rule.

The 41 coal mines in Silesia are mostly part of the Upper Silesian Coal Basin, which lies in the Silesian Upland. The coalfield has an area of about 4,500 km2 (1,700 sq mi).[21] Deposits in Lower Silesia have proven to be difficult to exploit and the area's unprofitable mines were closed in 2000.[21] In 2008, an estimated 35 billion tonnes of lignite reserves were found near Legnica, making them some of the largest in the world.[22]

From the fourth century BC, iron ore has been mined in the upland areas of Silesia.[21] The same period had lead, copper, silver, and gold mining. Zinc, cadmium, arsenic,[23] and uranium[24] have also been mined in the region. Lower Silesia features large copper mining and processing between the cities of Legnica, Głogów, Lubin, and Polkowice. In the Middle Ages, gold (Polish: złoto) and silver (Polish: srebro) were mined in the region, which is reflected in the names of the former mining towns of Złotoryja, Złoty Stok and Srebrna Góra.

The region is known for stone quarrying to produce limestone, marl, marble, and basalt.[21]

| Mineral Name | Production (tonnes) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bituminous coal | 95,000,000 | |

| Copper | 571,000 | [25] |

| Zinc | 160,000 | [26] |

| Silver | 1,200 | [27] |

| Cadmium | 500 | [28] |

| Lead | 70,000 | [29] |

The region also has a thriving agricultural sector, which produces cereals (wheat, rye, barley, oats, corn), potatoes, rapeseed, sugar beets and others. Milk production is well developed. The Opole Silesia has for decades occupied the top spot in Poland for their indices of effectiveness of agricultural land use.[30]

Mountainous parts of southern Silesia feature many significant and attractive tourism destinations (e.g., Karpacz, Szczyrk, Wisła). Silesia is generally well forested. This is because greenness is generally highly desirable by the local population, particularly in the highly industrialized parts of Silesia.

Demographics

editSilesia has been historically diverse in every aspect. Nowadays, the largest part of Silesia is located in Poland; it is often cited as one of the most diverse regions in that country.

The United States Immigration Commission, in its Dictionary of Races or Peoples (published in 1911, during a period of intense immigration from Silesia to the United States), considered Silesian as a geographical (not ethnic) term, denoting the inhabitants of Silesia. It is also mentioned the existence of both Polish Silesian and German Silesian dialects in that region.[31][32]

Ethnicity

editModern Silesia is inhabited by Poles, Silesians, Germans, and Czechs. Germans first came to Silesia during the Late Medieval Ostsiedlung.[34] The last Polish census of 2011 showed that the Silesians are the largest ethnic or national minority in Poland, Germans being the second; both groups are located mostly in Upper Silesia. The Czech part of Silesia is inhabited by Czechs, Moravians, Silesians, and Poles.

In the early 19th century the population of the Prussian part of Silesia was between 2/3 and 3/4 German-speaking, between 1/5 and 1/3 Polish-speaking, with Sorbs, Czechs, Moravians and Jews forming other smaller minorities (see Table 1. below).

Before the Second World War, Silesia was inhabited mostly by Germans, with Poles a large minority, forming a majority in Upper Silesia.[35] Silesia was also the home of Czech and Jewish minorities. The German population tended to be based in the urban centres and in the rural areas to the north and west, whilst the Polish population was mostly rural and could be found in the east and in the south.[36]

| Ethnic group | acc. G. Hassel in 1819[37] | % | acc. S. Plater in 1823[38] | % | acc. T. Ładogórski in 1787[39] | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germans | 1,561,570 | 75.6 | 1,550,000 | 70.5 | 1,303,300 | 74.6 |

| Poles | 444,000 | 21.5 | 600,000 | 27.3 | 401,900 | 23.0 |

| Sorbs | 24,500 | 1.2 | 30,000 | 1.4 | 900 | 0.1 |

| Czechs | 5,500 | 0.3 | 32,600 | 1.9 | ||

| Moravians | 12,000 | 0.6 | ||||

| Jews | 16,916 | 0.8 | 20,000 | 0.9 | 8,900 | 0.5 |

| Population | c. 2.1 million | 100 | c. 2.2 million | 100 | c. 1.8 million | 100 |

Ethnic structure of Prussian Upper Silesia (Opole regency) during the 19th century and the early 20th century can be found in Table 2.:

| Table 2. Numbers of Polish, German and other inhabitants (Regierungsbezirk Oppeln)[37][40][41] | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1819 | 1831 | 1834 | 1837 | 1840 | 1843 | 1846 | 1852 | 1855 | 1858 | 1861 | 1867 | 1890 | 1900 | 1905 | 1910 | |

| Polish | 377,100

(67.2%) |

418,837

(62.0%) |

468,691

(62.6%) |

495,362

(62.1%) |

525,395

(58.6%) |

540,402

(58.1%) |

568,582

(58.1%) |

584,293

(58.6%) |

590,248

(58.7%) |

612,849

(57.3%) |

665,865

(59.1%) |

742,153

(59.8%) |

918,728 (58.2%) | 1,048,230 (56.1%) | 1,158,805 (57.0%) | Census, monolingual Polish: 1,169,340 (53.0%)[42]

or up to 1,560,000 together with bilinguals | |

| German | 162,600

(29.0%) |

257,852

(36.1%) |

266,399

(35.6%) |

290,168

(36.3%) |

330,099

(36.8%) |

348,094

(37.4%) |

364,175

(37.2%) |

363,990

(36.5%) |

366,562

(36.5%) |

406,950

(38.1%) |

409,218

(36.3%) |

457,545

(36.8%) |

566,523 (35.9%) | 684,397 (36.6%) | 757,200 (37.2%) | 884,045 (40.0%) | |

| Other | 21,503

(3.8%) |

13,254

(1.9%) |

13,120

(1.8%) |

12,679

(1.6%) |

41,570

(4.6%) |

42,292

(4.5%) |

45,736

(4.7%) |

49,445

(4.9%) |

48,270

(4.8%) |

49,037

(4.6%) |

51,187

(4.6%) |

41,611

(3.4%) |

92,480

(5.9%) |

135,519

(7.3%) |

117,651

(5.8%) |

Total population: 2,207,981 | |

The Austrian part of Silesia had a mixed German, Polish and Czech population, with Polish-speakers forming a majority in Cieszyn Silesia.[43]

Religion

editHistorically, Silesia was about equally split between Protestants (overwhelmingly Lutherans) and Roman Catholics. In an 1890 census taken in the German part, Roman Catholics made up a slight majority of 53%, while the remaining 47% were almost entirely Lutheran.[44] Geographically speaking, Lower Silesia was mostly Lutheran except for the Glatzer Land (now Kłodzko County). Upper Silesia was mostly Roman Catholic except for some of its northwestern parts, which were predominantly Lutheran. Generally speaking, the population was mostly Protestant in the western parts, and it tended to be more Roman Catholic the further east one went. In Upper Silesia, Protestants were concentrated in larger cities and often identified as German. After World War II, the religious demographics changed drastically as Germans, who constituted the bulk of the Protestant population, were forcibly expelled. Poles, who were mostly Roman Catholic, were resettled in their place. Today, Silesia remains predominantly Roman Catholic.

Existing since the 12th century,[45] Silesia's Jewish community was concentrated around Wrocław and Upper Silesia, and numbered 48,003 (1.1% of the population) in 1890, decreasing to 44,985 persons (0.9%) by 1910.[46] In Polish East Upper Silesia, the number of Jews was around 90,000–100,000.[47] Historically, the community had suffered a number of localised expulsions such as their 1453 expulsion from Wrocław.[48] From 1712 to 1820 a succession of men held the title Chief Rabbi of Silesia ("Landesrabbiner"): Naphtali ha-Kohen (1712–16); Samuel ben Naphtali (1716–22); Ḥayyim Jonah Te'omim (1722–1727); Baruch b. Reuben Gomperz (1733–54); Joseph Jonas Fränkel (1754–93); Jeremiah Löw Berliner (1793–99); Lewin Saul Fränkel (1800–7); Aaron Karfunkel (1807–16); and Abraham ben Gedaliah Tiktin (1816–20).[49]

Consequences of World War II

editAfter the German invasion of Poland in 1939, following Nazi racial policy, the Jewish population of Silesia was subjected to Nazi genocide with executions performed by Einsatzgruppe z. B.V. led by Udo von Woyrsch and Einsatzgruppe I led by Bruno Streckenbach,[50][51] imprisonment in ghettos and ethnic cleansing to the General Government. In their efforts to exterminate the Jews through murder and ethnic cleansing Nazi established in Silesia province the Auschwitz and Gross-Rosen camps. Expulsions were carried out openly and reported in the local press.[52] Those sent to ghettos would from 1942 be expelled to concentration and work camps.[53] Between 5 May and 17 June, 20,000 Silesian Jews were sent to Birkenau to gas chambers[54] and during August 1942, 10,000 to 13,000 Silesian Jews were murdered by gassing at Auschwitz.[55] Most Jews in Silesia were exterminated by the Nazis. After the war Silesia became a major centre for repatriation of the Jewish population in Poland which survived Nazi German extermination[56] and in autumn 1945, 15,000 Jews were in Lower Silesia, mostly Polish Jews returned from territories now belonging to Soviet Union,[57] rising in 1946 to seventy thousand[58] as Jewish survivors from other regions in Poland were relocated.[59]

The majority of Germans fled or were expelled from the present-day Polish and Czech parts of Silesia during and after World War II. From June 1945 to January 1947, 1.77 million Germans were expelled from Lower Silesia, and 310,000 from Upper Silesia.[60] Today, most German Silesians and their descendants live in the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany, many of them in the Ruhr area working as miners, like their ancestors in Silesia. One of its most notable but controversial spokesmen was the Christian Democratic Union politician Herbert Hupka.

The expulsion of Germans led to widespread underpopulation. The population of the town of Głogów fell from 33,500 to 5,000, and from 1939 to 1966 the population of Wrocław fell by 25%.[61] Attempts to repopulate Silesia proved unsuccessful in the 1940s and 1950s,[62] and Silesia's population did not reach pre-war levels until the late 1970s. The Polish settlers who repopulated Silesia were partly from the former Polish Eastern Borderlands, which was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939. Wrocław was partly repopulated with refugees from the formerly Polish city of Lwów.

Cities and towns

editThe following table includes the cities and towns in Silesia with a population greater than 20,000 (2022).

| Name | Population | Area | Country | Administrative | Historic subregion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wrocław | 673,923 | 293 km2 (113 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 2 | Ostrava* | 283,504 | 214 km2 (83 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia/Moravia | ||

| 3 | Katowice | 281,418 | 165 km2 (64 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 4 | Gliwice | 171,896 | 134 km2 (52 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 5 | Bielsko-Biała* | 167,509 | 125 km2 (48 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia/Lesser Poland | ||

| 6 | Zabrze | 156,082 | 80 km2 (31 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 7 | Bytom | 150,594 | 69 km2 (27 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 8 | Zielona Góra | 139,503 | 58 km2 (22 sq mi) | Lubusz Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 9 | Rybnik | 132,266 | 148 km2 (57 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 10 | Ruda Śląska | 132,040 | 78 km2 (30 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 11 | Opole | 126,623 | 97 km2 (37 sq mi) | Opole Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 12 | Tychy | 123,562 | 82 km2 (32 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 13 | Chorzów | 102,564 | 33 km2 (13 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 14 | Wałbrzych | 102,490 | 85 km2 (33 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 15 | Legnica | 93,473 | 56 km2 (22 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 16 | Jastrzębie-Zdrój | 83,477 | 85 km2 (33 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 17 | Jelenia Góra | 76,174 | 109 km2 (42 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 18 | Mysłowice | 71,849 | 66 km2 (25 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 19 | Lubin | 68,775 | 41 km2 (16 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 20 | Havířov | 68,245 | 32 km2 (12 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 21 | Siemianowice Śląskie | 64,139 | 25 km2 (10 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 22 | Głogów | 63,240 | 35 km2 (14 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 23 | Żory | 61,835 | 65 km2 (25 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 24 | Tarnowskie Góry | 61,413 | 84 km2 (32 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 25 | Piekary Śląskie | 57,148 | 40 km2 (15 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 26 | Kędzierzyn-Koźle | 55,623 | 124 km2 (48 sq mi) | Opole Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 27 | Görlitz** | 55,519 | 68 km2 (26 sq mi) | Saxony | Historically part of Lusatia, Görlitz was considered part of Lower Silesia in years 1319–1329 and 1815–1945 | ||

| 28 | Opava | 55,512 | 91 km2 (35 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 29 | Frýdek-Místek* | 54,188 | 52 km2 (20 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia/Moravia | ||

| 30 | Świdnica | 53,797 | 22 km2 (8 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 31 | Świętochłowice | 51,824 | 13 km2 (5 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 32 | Racibórz | 50,419 | 75 km2 (29 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 33 | Karviná | 50,172 | 58 km2 (22 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 34 | Wodzisław Śląski | 45,316 | 50 km2 (19 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 35 | Nysa | 41,441 | 27 km2 (10 sq mi) | Opole Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 36 | Mikołów | 41,383 | 79 km2 (31 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 37 | Bolesławiec | 37,355 | 24 km2 (9 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 38 | Nowa Sól | 36,479 | 22 km2 (8 sq mi) | Lubusz Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 39 | Knurów | 36,044 | 34 km2 (13 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 40 | Oleśnica | 35,503 | 21 km2 (8 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 41 | Czechowice-Dziedzice | 34,972 | 33 km2 (13 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 42 | Třinec | 34,306 | 85 km2 (33 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 43 | Brzeg | 33,962 | 15 km2 (6 sq mi) | Opole Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 44 | Cieszyn | 33,486 | 29 km2 (11 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 45 | Oława | 33,158 | 27 km2 (10 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 46 | Hoyerswerda** | 31,326 | 96 km2 (37 sq mi) | Saxony | Historically part of Lusatia, Hoyerswerda was considered part of Lower Silesia in years 1825–1945 | ||

| 47 | Dzierżoniów | 31,256 | 20 km2 (8 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 48 | Zgorzelec** | 29,371 | 16 km2 (6 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Historically part of Lusatia, Zgorzelec was considered part of Lower Silesia in years 1319–1329 and 1815–1945 | ||

| 49 | Bielawa | 28,475 | 36 km2 (14 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 50 | Orlová | 27,966 | 25 km2 (10 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 51 | Żagań | 23,949 | 40 km2 (15 sq mi) | Lubusz Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 52 | Český Těšín | 23,487 | 34 km2 (13 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 53 | Lubliniec | 23,406 | 89 km2 (34 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 54 | Krnov | 22,848 | 44 km2 (17 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 55 | Kluczbork | 22,418 | 12 km2 (5 sq mi) | Opole Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 56 | Świebodzice | 22,002 | 30 km2 (12 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 57 | Orzesze | 21,758 | 84 km2 (32 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 58 | Polkowice | 21,585 | 24 km2 (9 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 59 | Łaziska Górne | 21,371 | 21 km2 (8 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia | ||

| 60 | Świebodzin | 21,112 | 11 km2 (4 sq mi) | Lubusz Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 61 | Jawor | 21,077 | 19 km2 (7 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 62 | Nowa Ruda | 20,831 | 37 km2 (14 sq mi) | Lower Silesian Voivodeship | Lower Silesia | ||

| 63 | Bohumín | 20,648 | 31 km2 (12 sq mi) | Moravian-Silesian Region | Czech Silesia | ||

| 64 | Rydułtowy | 20,436 | 15 km2 (6 sq mi) | Silesian Voivodeship | Upper Silesia |

* Only part in Silesia

Flags and coats of arms

editThe emblems of Lower Silesia and Upper Silesia originate from the emblems of the Piasts of Lower Silesia and Upper Silesia. The coat of arms of Upper Silesia depicts the golden eagle on the blue shield. The coat of arms of Lower Silesia depicts a black eagle on a golden (yellow) shield.

-

Coat of arms of the Prussian province of Upper Silesia (1919–1938 and 1941–1945)

-

Henryk IV's Probus coat of arms

-

Coat of arms of Austrian Silesia (1742–1918)

-

Prussian province of Lower Silesia (1919–1938 and 1941–1945)

-

Coat of arms of the Lower Silesia Voivodeship

-

Coat of arms of Czech Silesia

Flags with their colors refer to the coat of arms of Silesia.

-

Flag of Prussian Upper Silesia province (1919–1938 and 1941–1945)

-

Flag of Silesia Voivodeship

-

Flag of the Austrian Silesia (1742–1918), and Czech Silesia

-

Flag of Prussian Lower Silesia province (1919–1938 and 1941–1945)

-

Flag of Lower Silesia Voivodeship

World Heritage Sites

editSee also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Silesia". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Silesia". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Silesia". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019.

- ^ "Silesia". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Zbigniew Babik, "Najstarsza warstwa nazewnicza na ziemiach polskich w granicach średniowiecznej Słowiańszczyzny", Uniwersitas, Kraków, 2001.

- ^ Rudolf Fischer. Onomastica slavogermanica. Uniwersytet Wrocławski. 2007. t. XXVI. 2007. str. 83

- ^ Jankuhn, Herbert; Beck, Heinrich; et al., eds. (2006). "Wandalen". Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 33 (2nd ed.). Berlin, Germany; New York City: de Gruyter.

Da die Silingen offensichtlich ihren Namen im mittelalterlichen pagus silensis und dem mons slenz – möglicherweise mit dem Zobten gleichzusetzen [...] – hinterließen und damit einer ganzen Landschaft – Schlesien – den Namen gaben [...]

- ^ Andreas Lawaty, Hubert Orłowski (2003). Deutsche und Polen: Geschichte, Kultur, Politik (in German). C.H.Beck. p. 183.

- ^ R. Żerelik(in:) M. Czpliński (red.) Historia Śląska, Wrocław 2007, pp. 34–35

- ^ R. Żerelik(in:) M. Czpliński (red.) Historia Śląska, Wrocław 2007, pp. 37–38

- ^ a b c R. Żerelik(in:) M. Czpliński (red.) Historia Śląska, Wrocław 2007, pp. 21–22

- ^ Zientara, Benedykt (1975). "Walonowie na Śląsku w XII i XIII wieku". Przegląd Historyczny (in Polish). No. 66/3. pp. 353, 357.

- ^ R. Żerelik(in:) M. Czpliński (red.) Historia Śląska, Wrocław 2007, p. 81

- ^ gonschior.de (in German)

- ^ Piotr Eberhardt, Political Migrations in Poland, 1939–1948, Warsaw 2006, p.25

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN.

- ^ Kamila Uzarczyk: Podstawy ideologiczne higieny ras. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek, 2002, pp. 285, 286, 289. ISBN 83-7322-287-1.

- ^ Geoffrey K. Roberts, Patricia Hogwood (2013). The Politics Today Companion to West European Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9781847790323.; Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. p. 303. ISBN 9780674926851.; Phillip A. Bühler (1990). The Oder-Neisse Line: a reappraisal under internaromtional law. East European Monographs. p. 33. ISBN 9780880331746.

- ^ Lukowski, Zawadski, Jerzy, Hubert (2006). A Concise History of Poland. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–280. ISBN 978-0-521-61857-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Natural Resources | poland.gov.pl". En.poland.gov.pl. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ "Mamy największe złoża węgla brunatnego na świecie" (in Polish). Gazetawyborcza.pl. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ S.Z. Mikulski, "Late-Hercynian gold-bearing arsenic-polymetallic mineralization within Saxothuringian zone in the Polish Sudetes, Northeast Bohemian Massif". In: "Mineral Deposit at the Beginning of the 21st Century", A. Piestrzyński et al. (eds). Swets & Zeitinger Publishers (Google books)

- ^ "Wise International | World Information Service on Energy". 0.antenna.nl. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Copper: World Smelter Production, By Country". Indexmundi.com. 28 July 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Zinc: World Smelter Production, By Country". Indexmundi.com. 1 July 2004. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Silver: World Mine Production, By Country". Indexmundi.com. 13 August 2004. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Cadmium: World Refinery Production, By Country". Indexmundi.com. 18 May 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Lead: World Refinery Production, By Country". Indexmundi.com. 24 June 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Samorząd Województwa Opolskiego". Umwo.opole.pl. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Dillingham, William Paul; Folkmar, Daniel; Folkmar, Elnora (1911). Dictionary of Races or Peoples. Washington, D.C.: Washington, Government Printing Office. p. 128.

- ^ Dillingham, William Paul; Folkmar, Daniel; Folkmar, Elnora (1911). Dictionary of Races or Peoples. United States. Immigration Commission (1907–1910). Washington, D.C.: Washington, Government Printing Office. pp. 105, 128.

- ^ "Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa – biblioteka cyfrowa regionu śląskiego – Wznowione powszechne taxae-stolae sporządzenie, Dla samowładnego Xięstwa Sląska, Podług ktorego tak Auszpurskiey Konfessyi iak Katoliccy Fararze, Kaznodzieie i Kuratusowie Zachowywać się powinni. Sub Dato z Berlina, d. 8. Augusti 1750". Sbc.org.pl. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Weinhold, Karl (1887). Die Verbreitung und die Herkunft der Deutschen in Schlesien [The Spread and the Origin of Germans in Silesia] (in German). Stuttgart: J. Engelhorn.

- ^ Jobst Gumpert (1966). Polen, Deutschland (in German). Callwey. p. 138.

- ^ Hunt Tooley, T (1997). National Identity and Weimar Germany: Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918–1922, University of Nebraska Press, p.17.

- ^ a b Georg Hassel (1823). Statistischer Umriß der sämmtlichen europäischen und der vornehmsten außereuropäischen Staaten, in Hinsicht ihrer Entwickelung, Größe, Volksmenge, Finanz- und Militärverfassung, tabellarisch dargestellt; Erster Heft: Welcher die beiden großen Mächte Österreich und Preußen und den Deutschen Staatenbund darstellt (in German). Verlag des Geographischen Instituts Weimar. pp. 33–34.

- ^ Plater, Stanisław (1825). Jeografia wschodniey części Europy czyli opis krajów przez wielorakie narody sławiańskie zamieszkanych obeymujący Prussy, Xięztwo Poznańskie, Szląsk Pruski, Gallicyą, Rzeczpospolitę Krakowską, Królestwo Polskie i Litwę (in Polish). Wrocław: Wilhelm Bogumił Korn. p. 60.

- ^ Ładogórski, Tadeusz (1966). Ludność, in: Historia Śląska, vol. II: 1763–1850, part 1: 1763–1806 (in Polish). Wrocław: edited by W. Długoborski. p. 150.

- ^ Paul Weber (1913). Die Polen in Oberschlesien: eine statistische Untersuchung (in German). Berlin: Verlagsbuchhandlung von Julius Springer.

- ^ Kalisch, Johannes; Bochinski, Hans (1958). "Stosunki narodowościowe na Śląsku w świetle relacji pruskich urzędników z roku 1882" (PDF). Śląski Kwartalnik Historyczny Sobótka. 13. Leipzig. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2020.

- ^ Paul Weber (1913). Die Polen in Oberschlesien: eine statistische Untersuchung (in German). Berlin: Verlagsbuchhandlung von Julius Springer. p. 27.

- ^ Chromik, Grzegorz. Geschichte des deutsch-slawischen Sprachkontaktes im Teschener Schlesien (in German). pp. 258–322. ISBN 978-3-88246-398-9.

- ^ Meyers Konversationslexikon 5. Auflage

- ^ Demshuk, A (2012) The Lost German East: Forced Migration and the Politics of Memory, 1945–1970, Cambridge University Press P40

- ^ Kamusella, T (2007). Silesia and Central European nationalisms: the emergence of national and ethnic groups in Prussian Silesia and Austrian Silesia, 1848–1918, Purdue University Press, p.173.

- ^ Christopher R. Browning (2000). Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p.147.

- ^ van Straten, J (2011) The Origin of Ashkenazi Jewry: The Controversy Unravelled, Walter de Gruyter P58

- ^ "Silesia". 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ Popularna encyklopedia powszechna – Volume 10 – Page 660 Magdalena Olkuśnik, Elżbieta Wójcik – 2001 Streckenbach Bruno (1902–1977), funkcjonariusz niem. państwa nazistowskiego, Gruppenfuhrer SS. Od 1933 szef policji po- lit w Hamburgu. 1939 dow. Einsatzgruppe I (odpowiedzialny za eksterminacje ludności pol. i żydowskiej na Śląsku).

- ^ Zagłada Żydów na polskich terenach wcielonych do Rzeszy Page 53 Aleksandra Namysło, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej—Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu – 2008 W rzeczywistości ludzie Udona von Woyr- scha podczas marszu przez województwo śląskie na wschód dopuszczali się prawdziwych masakr ludności żydowskiej.

- ^ Steinbacher, S. "In the Shadow of Auschwitz, The murder of the Jews of East Upper Silesia", in Cesarani, D. (2004) Holocaust: From the persecution of the Jews to mass murder, Routledge, P126

- ^ Steinbacher, S. "In the Shadow of Auschwitz, The murder of the Jews of East Upper Silesia", in Cesarani, D. (2004) Holocaust: From the persecution of the Jews to mass murder, Routledge, pp.110–138.

- ^ The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942 – Page 544 Christopher R. Browning – 2007 Between 5 May and 17 June, 20,000 Silesian Jews were deported to Birkenau to be gassed.

- ^ Christopher R. Browning (2007). The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942, University of Nebraska Press, p.544.

- ^ The International Jewish Labor Bund After 1945: Toward a Global History David Slucki, page 63

- ^ A narrow bridge to life: Jewish forced labor and survival in the Gross-Rosen camp system, 1940–1945, page 229 Belah Guṭerman

- ^ Kochavi, AJ (2001)Post-Holocaust politics: Britain, the United States & Jewish refugees, 1945–1948, University of North Carolina Press P 176

- ^ Kochavi, AJ (2001). Post-Holocaust politics: Britain, the United States & Jewish refugees, 1945–1948, University of North Carolina Press, p.176.

- ^ DB Klusmeyer & DG Papademetriou (2009). Immigration policy in the Federal Republic of Germany: negotiating membership and remaking the nation, Berghahn, p.70.

- ^ Scholz, A (1964). Silesia: yesterday and today, Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague, p.69.

- ^ Mazower, M (1999). Dark Continent: Europe's 20th Century, Penguin, p.223.

- ^ Łęknica and Bad Muskau were considered part of Silesia in years 1815–1945.

Sources

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–92.

- Czapliński, Marek; Wiszewski, Przemysław, eds. (2014). "Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia" (PDF). Region Divided - Times of Nation-States (1918-1945). Vol. 4. Wrocław, Poland: ebooki.com.pl. ISBN 978-83-927132-8-9. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Długajczyk, Edward (1993). Tajny front na granicy cieszyńskiej. Wywiad i dywersja w latach 1919–1939. Katowice: Śląsk. ISBN 83-85831-03-7.

- Harc, Lucyna; Wąs, Gabriela, eds. (2014). "Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia" (PDF). The Strengthening of Silesian Regionalism (1526-1740). Vol. 2. Wrocław, Poland: ebooki.com.pl. ISBN 978-83-927132-6-5. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Harc, Lucyna; Kulak, Teresa, eds. (2015). "Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia" (PDF). Silesia under the Authority of the Hohenzollerns (1741-1918). Vol. 3. Wrocław, Poland: ebooki.com.pl. ISBN 978-83-942651-3-7. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Przemysław, Wiszewski, ed. (2013). "Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia" (PDF). The Long Formation of the Region (c. 1000–1526). Vol. 1. Wrocław, Poland: ebooki.com.pl. ISBN 978-83-927132-1-0. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Wiszewski, Przemysław, ed. (2015). "Cuius regio? Ideological and Territorial Cohesion of the Historical Region of Silesia" (PDF). Permanent Change - The New Region(s) of Silesia (1945-2015). Vol. 5. Wrocław, Poland: ebooki.com.pl. ISBN 978-83-942651-2-0. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Zahradnik, Stanisław; Marek Ryczkowski (1992). Korzenie Zaolzia. Warszawa - Praga - Trzyniec: PAI-press. OCLC 177389723.