The Margraviate of Brandenburg (German: Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

March/Margraviate of Brandenburg Mark/Markgrafschaft Brandenburg (German) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1157–1806 | |||||||||||||||

Top: Flag or naval ensign c. 1684 (based on L. Verschuier's painting[2])

Bottom: Flag 1660–1750 used by Hohenzollerns | |||||||||||||||

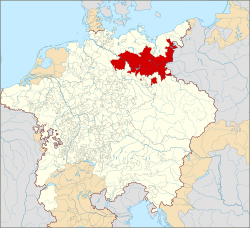

Margraviate of Brandenburg within the Holy Roman Empire (1618) | |||||||||||||||

| Status | State of the Holy Roman Empire Imperial elector (1356–1806) Crown land of the Bohemian Crown (1373–1415) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Brandenburg an der Havel (1157–1417) Berlin (1417–1806) | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Low German, Lüneburg Wendish | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Dominant confession among the population was Roman Catholic until the 1530s, then Lutheran. Elector was Roman Catholic until 1539, then Lutheran until 1613, and then Reformed. | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Margrave | |||||||||||||||

• 1157–70 | Albert the Bear (first) 1417 | ||||||||||||||

• 1797–1806 | Frederick William III (last) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 3 October 1157 | ||||||||||||||

• Raised to Electorate | 25 December 1356 | ||||||||||||||

| 27 August 1618 | |||||||||||||||

| 18 January 1701 | |||||||||||||||

• Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire | 6 August 1806 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Brandenburg developed out of the Northern March founded in the territory of the Slavic Wends. It derived one of its names from this inheritance, the March of Brandenburg (Mark Brandenburg). Its ruling margraves were established as prestigious prince-electors in the Golden Bull of 1356, allowing them to vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The state thus became additionally known as Electoral Brandenburg or the Electorate of Brandenburg (Kurbrandenburg or Kurfürstentum Brandenburg).

The House of Hohenzollern came to the throne of Brandenburg in 1415. In 1417, Frederick I moved its capital from Brandenburg an der Havel to Berlin. By 1535, the electorate had an area of some 10,000 square miles (26,000 km2) and a population of 400,000.[3] Under Hohenzollern leadership, Brandenburg grew rapidly in power during the 17th century and inherited the Duchy of Prussia. The resulting Brandenburg-Prussia was the predecessor of the Kingdom of Prussia, which became a leading German state during the 18th century. Although the electors' highest title was "King in/of Prussia", their power base remained in Brandenburg and its capital Berlin.

The Margraviate of Brandenburg ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. It was replaced after the Napoleonic Wars with the Prussian Province of Brandenburg in 1815. The Hohenzollern Kingdom of Prussia was the primary driving force behind the unification of Germany. The Prussian-dominated North German Confederation later transformed in 1871 into the German Empire; it was the legal predecessor of the united German Reich of 1871–1945, and as such a direct ancestor of the present-day Federal Republic of Germany,

Geography edit

The territory of the former margraviate, commonly known as the Mark Brandenburg,[citation needed] lies in present-day eastern Germany and western Poland. Geographically it encompassed the majority of the present-day German states of Brandenburg and Berlin, the Altmark (the northern third of Saxony-Anhalt), and the Neumark (now divided between Poland's Lubusz and West Pomeranian Voivodeships). Parts of the present-day federal state Brandenburg, such as Lower Lusatia and territory which had been Saxon until 1815, were not parts of the Mark. Colloquially but not accurately, the federal state Brandenburg is sometimes identified as the Mark or Mark Brandenburg.

The region was formed during the ice age, and characterized by moraines, glacial valleys, and numerous lakes. The territory is known as a Mark or march because it was a border county of the Holy Roman Empire (see also Margraviate of Meissen).

The Mark is defined by two uplands and two depressions. The depressions are taken up by rivers and chains of lakes with marsh and boggy soil along the shores; once used for peat collection, the riverbanks are now mostly drained and dry.[citation needed]

The Northern or Baltic Uplands of the Mecklenburg Lake Plateau have only minor extensions into Brandenburg. The approximately 230 km-long range of hills in the Mark's south begins in the Lusatian Highlands (near Żary (Sorau)) and continues past Trzebiel (Triebel) and Spremberg, then to the northwest through Calau, and ends in the bare and dry Fläming. The southern depression is generally to the north of this ridge and appears strikingly in the Spreewald (between Baruth/Mark and Plaue an der Havel). The northern depression, lying almost directly south of the Baltic uplands, is defined by the lowlands of the Noteć and Warta Rivers, the Oderbruch, the valley of the Finow, the Havelland moor, and the Oder River.

Between these two depressions is a low plateau that extends from the Poznań area westward to Brandenburg through Torzym (Sternberg), the Spree plateau, and the Mittelmark. From southeast to northwest, this plateau is intersected by the lowland of the Leniwa Obra and the Oder River below the confluence of the Lusatian Neisse, the lower Spree Valley, and the Havel Valley. Between these valleys rise a series of hills and plateaus, such as the Barnim, the Teltow, the Semmelberg near Bad Freienwalde (157 m, 515 ft), the Müggelberge in Köpenick (115 m, 377 ft), the Havelberge (97 m, 318 ft), and the Rauen Hills near Fürstenwalde (112 to 152 m, 367 to 499 ft).

The region is predominantly marked by dry, sandy soil, wide stretches of which have pine trees and erica plants, or heath. However, the soil is loamy in the uplands and plateaus and, when farmed appropriately, can be agriculturally productive.[citation needed]

Mark Brandenburg has a cool, continental climate, with temperatures averaging near 0 °C (32 °F) in January and February and near 18 °C (64 °F) in July and August. Precipitation averages between 500 mm and 600 mm annually, with a modest summer maximum.

History edit

Northern March edit

By the eighth century, Slavic Wends, such as the Sprewane and Hevelli (Havolane or Stodorans), started to move into the Brandenburg area. They intermarried with Saxons and Bohemians.

The Bishoprics of Brandenburg and Havelberg were established at the beginning of the tenth century (in 928 and 948, respectively).[4] They were suffragan to the Archbishopric of Mainz; the Bishopric of Brandenburg reached to the Baltic Sea.

King Henry the Fowler started governing in the region in 928–929, allowing Emperor Otto I to establish the Northern March under Margrave Gero in 936 during the German Ostsiedlung. However, the march and the bishoprics were overthrown by a Slavic rebellion in 983; until the collapse of the Liutizian alliance in the middle of the 11th century, the Holy Roman Empire government through bishoprics and marches came nearly to a standstill for approximately 150 years,[5] even though the bishopric was retained.

Prince Pribislav of the Hevelli came to power at the castle of Brenna (Brandenburg an der Havel) in 1127. During Pribislav's reign, in which he cultivated close connections with the German nobility, Germans succeeded in binding to the Holy Roman Empire the Havolane region from Brandenburg an der Havel to Spandau. The disputed eastern border continued between the Hevelli and the Sprewane, recognized as the Havel-Nuthe line. Prince Jaxa of Köpenick (Jaxa de Copnic) of the Sprewane lived in Köpenick east of the dividing line.

Ascanians edit

During the second phase of the German Ostsiedlung, Albert the Bear began the expansionary eastern policy of the Ascanians. From 1123 to 1125 Albert developed contacts with Pribislav, who served as the godfather for the Ascanian's first son, Otto, and gave the boy the Zauche region as a christening present in 1134. In the same year, Emperor Lothair III named Albert margrave of the Northern March and raised Pribislav to the status of king, although that was later rescinded. Also in 1134, Albert succeeded in securing for the Ascanians the inheritance of the childless Pribislav. After the latter's death in 1150, Albert received the Havolane residence of Brenna. The Ascanians also began to build the castle of Spandau.

In contrast to their leaders who had accepted Christianity, the Havolane population still worshipped old Slavic deities and opposed Albert's assumption of power. Jaxa of Köpenick, a possible relative of Pribislav and a claim-holder to Brandenburg, controlled Brandenburg with Polish help, and ruled the land of the Stodorans. Older historical research dates this conquest to 1153, although there are no definite sources for the date. More recent researchers (such as Lutz Partenheimer) date it to spring 1157, as it is doubtful that Albert would not have responded to Jaxa's actions for four years.

With bloody victories on 11 June 1157, Albert the Bear was able to reconquer Brandenburg, exile Jaxa, and found a new lordship. Because he already held the title of margrave, Albert styled himself as Margrave of Brandenburg (Adelbertus Dei gratia marchio in Brandenborch) on 3 October 1157, thereby beginning the Margraviate of Brandenburg.

The territorial limits of the original margraviate differed from the area of the current Bundesland Brandenburg, consisting merely of the Havelland and Zauche regions. In the following 150 years the Ascanians succeeded in winning the Uckermark, Teltow, and Barnim regions east of the Havel and Nuthe, thereby extending the Mark to the Oder River. The Neumark ("New March") east of the Oder was acquired gradually through purchases, marriages, and aid to the Piast dynasty of Poland.[6]

Because of the sandy soil prevalent in Brandenburg, the agriculturally meager principality was denigrated as "the sandbox of the Holy Roman Empire".[6] Albert invited colonists to settle the new territory, many of whom came from the Altmark ("Old March", a later name for the original Northern March), the Harz, Flanders (hence the Fläming region), and the Rhineland. After the capture of territory along the Elbe and Havel Rivers in the 1160s, Flemish and Dutch settlers from flooded regions in Holland used their expertise to build dikes in Brandenburg. Initially, the Ascanians protected the country by settling knights in villages; castles fortified with knights were mostly located in the border region of the Neumark. After a 14th-century decline in imperial power, however, knights began constructing castles throughout the principality, granting them more independence.[6]

After Albert's death in 1170, his son succeeded him as Otto I, Margrave of Brandenburg. The Ascanians pursued a policy of expanding to the east and the northeast with the goal of connecting their territories through Pomerania to the Baltic Sea. This policy brought them into conflict with the Kingdom of Denmark. After the Battle of Bornhöved (1227), Margrave John I staked his claim to Pomerania, receiving it as a fief from Emperor Frederick II in 1231. The middle of the 13th century was a time of important developments for the Ascanian House, as it won Stettin (Szczecin) and the Uckermark (1250), although the former was later lost to the Duchy of Pomerania.[5] Also around 1250 it took over Lubusz Land from then-fragmented Poland and subsequently conquered northwestern parts of the Duchy of Greater Poland in the late 13th century, moving the border east of the Oder river. Henry II, the last Ascanian margrave, died in 1320.

Wittelsbachs edit

Having defeated the Habsburgs, the Wittelsbach Emperor Louis IV, an uncle of Henry II, granted Brandenburg to his oldest son, Louis I (the "Brandenburger") in 1323. As a consequence of the murder of Provost Nikolaus von Bernau in 1325, Brandenburg was punished with a papal interdict. From 1328 onwards, Louis was in war against Pomerania which he claimed as a fiefdom and the conflict did not end before 1333. The rule of Margrave Louis I was rejected by the domestic nobility of Brandenburg, and, after the death of Emperor Louis IV in 1347, the margrave was confronted with the False Waldemar, an imposter of the deceased Margrave Waldemar. The pretender was recognized as Margrave of Brandenburg on 2 October 1348 by the new emperor, Charles IV of Luxembourg, but was exposed as a fraud after a peace between the Wittelsbachs and Luxembourgs at Eltville. In 1351 Louis gave the Mark to his younger half-brothers Louis II (the "Roman") and Otto V in exchange for the sole rule over Upper Bavaria.

Louis the Roman forced the False Waldemar to renounce his claims to Brandenburg and succeeded in establishing the Margraves of Brandenburg as prince-electors in the Golden Bull of 1356. Brandenburg therefore became a Kurfürstentum (literally "electoral principality" or "electorate") of the Holy Roman Empire and had a vote in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The Margrave of Brandenburg also held the ceremonial title of Arch-Chamberlain of the Empire (Latin: Archi-Camerarius Imperii). When Louis the Roman died in 1365, Otto took over the rule of Brandenburg, although he quickly neglected the march. He sold Lower Lusatia, which he had already pledged to the Wettin dynasty, to Emperor Charles IV in 1367. A year later he lost the town Deutsch Krone (Wałcz) to Polish King Casimir the Great.

Luxembourgs edit

After the middle of the 14th century, Emperor Charles IV attempted to secure Brandenburg for the House of Luxembourg. Control over the electoral vote of Brandenburg would help assure the Luxembourgs of election to the imperial throne, as they already held the vote of Bohemia. Charles succeeded in purchasing Brandenburg from Margrave Otto for 500,000 guilders in 1373 and, at a Landtag in Guben, he attached (but did not incorporate) Brandenburg to the Crown of Bohemia. The Landbuch ("land book", i.e. estate register) of Charles IV, a source for the history of medieval settlement in Brandenburg, originated during this time. Charles chose the castle of Tangermünde to be the electoral residence.

The power of the Luxembourgs in Brandenburg declined during the reign of Charles's nephew Jobst of Moravia. The Neumark was pawned to the Teutonic Knights, who neglected the border region. Under the Wittelsbach and Luxembourg margraves, Brandenburg fell increasingly under the control of the local nobility as central authority declined.[7]

Hohenzollerns edit

In return for supporting Sigismund as Holy Roman Emperor at Frankfurt in 1410, Frederick VI of Nuremberg, a burgrave of the House of Hohenzollern, was granted hereditary control over Brandenburg in 1411. Rebellious landed nobility such as the Quitzow family opposed his appointment, but Frederick overpowered these knights with artillery. Some nobles had their property confiscated, and the Brandenburg estates gave allegiance at Tangermünde on 20 March 1414.[8] Frederick was officially recognized as Margrave and Prince-elector Frederick I of Brandenburg at the Council of Constance in 1415. Frederick's formal investiture with the Kurmark, or electoral march, and his appointment as Archchamberlain of the Holy Roman Empire occurred on 18 April 1417, also during the Council of Constance.

Frederick made Berlin his residence, although he retired to his Franconian possessions in 1425. He granted governance of Brandenburg to his eldest son John the Alchemist, while retaining the electoral dignity for himself. The next elector, Frederick II, forced the submission of Berlin and Cölln, setting an example for the other towns of Brandenburg.[9] He reacquired the Neumark from the Teutonic Knights by the Treaties of Cölln and Mewe and began its rebuilding.

Years of warfare with the Duchy of Pomerania were ended by the treaties of Prenzlau (1448, 1472, and 1479).

Brandenburg accepted the Protestant Reformation in 1539. The population has remained largely Lutheran since, although some later electors converted to Calvinism.

The Hohenzollerns of Brandenburg sought to expand their power base from their relatively meager possessions, although this brought them into conflict with neighboring states. John William, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg died childless in 1609. His eldest niece, Anna, Duchess of Prussia, was the wife of John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, who promptly claimed the inheritance and sent troops to take hold of some of John William's holdings in the Rhineland. Unfortunately for John Sigismund, this effort became tied up with the Thirty Years' War and the disputed succession of Jülich. At the end of the war in 1648, Brandenburg was recognized as the possessor of approximately half the inheritance, comprising the Duchy of Cleves in the Rhineland and the Counties of Mark and Ravensberg in Westphalia. These territories, which were more than 100 kilometers from the borders of Brandenburg, formed the nucleus of the later Prussian Rhineland.

Brandenburg-Prussia edit

When Albert Frederick, Duke of Prussia, died without a son in 1618, his son-in-law John Sigismund inherited the Duchy of Prussia. He then ruled both territories in a personal union which came to be known as Brandenburg-Prussia. In this way, the fortuitous marriage of John Sigismund to Anna of Prussia, and the deaths of her maternal uncle in 1609 and her father in 1618 without immediate male heirs, proved to be the key events by which Brandenburg acquired territory both in the Rhineland and on the Baltic coast. Prussia lay outside the Holy Roman Empire and the electors of Brandenburg held it as a fief of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, to which the electors paid homage.

The electors of Brandenburg spent the next two centuries attempting to gain lands to unite their separate territories (the Mark Brandenburg, the territories in the Rhineland and Westphalia, and Ducal Prussia) to form one geographically contiguous domain. In the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years' War in 1648, Brandenburg-Prussia acquired Farther Pomerania and made it the Province of Pomerania by the Treaty of Stettin (1653). In the second half of the 17th century, Frederick William, the "Great Elector", developed Brandenburg-Prussia into a major power. The state constructed Brandenburg's first navy (Kurbrandenburgische Marine), leading to short-lived colonies at Arguin, the Brandenburger Gold Coast, and Saint Thomas. The electors succeeded in acquiring full sovereignty over Prussia in the treaties of Wehlau and Bromberg in 1657. The territories of the Hohenzollerns were opened to immigration by Huguenot refugees by the Edict of Potsdam in 1685.

Kingdom of Prussia edit

In return for aiding Emperor Leopold I during the War of the Spanish Succession, Frederick William's son, Frederick III, was allowed to elevate Prussia to the status of a kingdom. On 18 January 1701, Frederick crowned himself Frederick I, King in Prussia. Prussia, unlike Brandenburg, lay outside the Holy Roman Empire, within which only the emperor and the ruler of Bohemia could call themselves king. As king was a more prestigious title than prince-elector, the territories of the Hohenzollerns became known as the Kingdom of Prussia, although their power base remained in Brandenburg. Legally, Brandenburg was still part of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by the Hohenzollerns in personal union with the Prussian kingdom over which they were fully sovereign. For this reason, the Hohenzollerns continued to use the additional title of Elector of Brandenburg for the remainder of the empire's run. However, by this time the emperor's authority over the empire had become merely nominal. The various territories of the empire acted more or less as de facto sovereign states, and only acknowledged the emperor's overlordship over them in a formal way. Thus, Brandenburg came to be treated as de facto part of the Prussian kingdom rather than a separate entity.

From 1701 to 1946, Brandenburg's history was largely that of the state of Prussia, which established itself as a major power in Europe during the 18th century. King Frederick William I of Prussia, the "Soldier-King", modernized the Prussian Army, while his son Frederick the Great achieved glory and infamy with the Silesian Wars and Partitions of Poland. The feudal designation of the Margraviate of Brandenburg ended with the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, which made the Hohenzollerns de jure as well as de facto sovereigns over it. It was replaced with the Province of Brandenburg in 1815 following the Napoleonic Wars. The Prussian kings, however, continued to use the title "Margrave of Brandenburg" in their formal style.

Brandenburg, along with the rest of Prussia, became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the Prussian-led unification of Germany.

Later years edit

During the Gleichschaltung of provinces by Nazi Germany during the 1930s, the Province of Brandenburg and the Free State of Prussia lost all practical relevancy. The region was administered as the Gau "Mark Brandenburg".

The state of Prussia was de jure abolished in 1947 after the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II; the Gau "Mark Brandenburg" was replaced with the Land Brandenburg.

Brandenburg west of the Oder–Neisse line lay in the Soviet occupation zone; it became part of the German Democratic Republic. In 1952 the region was divided among the districts of Cottbus, Frankfurt (Oder), Potsdam, Schwerin, and Neubrandenburg; Berlin was divided between East Berlin and West Berlin.

This division of Brandenburg continued until the German reunification in 1990. The GDR districts were dissolved and replaced with the state of Brandenburg with its capital in Potsdam. The 850th anniversary of the foundation of the March of Brandenburg was celebrated officially on 11 June 2007, with preliminary celebrations at the Knights' Academy of Brandenburg an der Havel on 23 June 2006.

See also edit

Footnotes edit

- ^ Based on some original preserved depictions:

-

Berlin Bear with Brandenburg coat of arms, late 18th / Early 19th Century; Märkisches Museum Berlin

-

Ceiling painting (detail: female allegory with wreath of grain ears and the Brandenburg eagle), oil on canvas, 1751 (destroyed in World War II)

-

Museum Senftenberg (Senftenberg Castle)

-

- ^ Die kurbrandenburgische Flotte (1684)

- ^ Preserved Smith. The Social Background of the Reformation. 1920. Page 17.

- ^ Koch, p. 23.

- ^ a b Koch, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Koch, p. 25.

- ^ Koch, p. 28

- ^ Koch, p. 29.

- ^ Koch, p. 30.

References edit

- H.W. Koch (1978). A History of Prussia. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 326. ISBN 0-88029-158-3.

External links edit

- (in German) Hochmittelalter in der Mark Brandenburg at Brandenburg1260.de.

- (in German) Der Brandenburger Landstreicher

- Historical map of Brandenburg, 1789

- (in German) Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg by Theodor Fontane, 1899 at Lexikus.de.

![Coat of arms as Electorate[1] of Brandenburg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Arms_of_Brandenburg.svg/85px-Arms_of_Brandenburg.svg.png)