Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a class of antidepressant drugs used in the treatment of major depression and other mood disorders. They are sometimes also used to treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), chronic neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), and for the relief of menopausal symptoms.

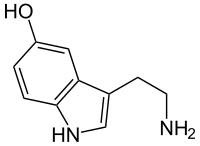

SNRIs act upon, and increase, the levels of two neurotransmitters in the brain known to play an important part in mood: serotonin, and norepinephrine. These can be contrasted with the more widely-used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) which act upon serotonin alone.

Overview of SNRIs

edit- Venlafaxine (Effexor) – The first and most commonly used SNRI. It was introduced by Wyeth in 1994. The reuptake effects of venlafaxine are dose-dependent. At low doses (<150 mg/day), it acts only on serotonergic transmission. At moderate doses (>150 mg/day), it acts on serotonergic and noradrenergic systems, whereas at high doses (>300 mg/day), it also affects dopaminergic neurotransmission.[1]

- Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq)[2] – The active metabolite of venlafaxine. It is believed to work in a similar manner, though some evidence suggests lower response rates compared to venlafaxine and duloxetine. It was introduced by Wyeth in May 2008.

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta, Yentreve)[3] – By Eli Lilly and Company, has been approved for the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain in August 2004. Duloxetine is contraindicated in patients with heavy alcohol use or chronic liver disease, as duloxetine can increase the levels of certain liver enzymes that can lead to acute hepatitis or other diseases in certain at risk patients. Currently, the risk of liver damage appears to be only for patients already at risk, unlike the antidepressant nefazodone, which, though rare, can spontaneously cause liver failure in healthy patients. [4] Duloxetine is also approved for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), chronic musculoskeletal pain, including chronic osteoarthritis pain and chronic low back pain (as of October, 2010), and is one of the only three medicines approved by the FDA for Fibromyalgia [1].

- Milnacipran (Dalcipran, Ixel, Savella)[5] – Shown to be significantly effective in the treatment of depression and fibromyalgia. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia in the United States of America in January 2009, however it is currently not approved for depression in that country. Milnacipran has been commercially available in Europe and Asia for several years.

- Levomilnacipran (F2695) – The levo- isomer of milnacipran. Under development for the treatment of depression in the United States and Canada.

- Sibutramine (Meridia, Reductil) – An SNRI, which, instead of being developed for the treatment of depression, was widely marketed as an appetite suppressant for weight loss purposes.

- Bicifadine (DOV-220,075) – By DOV Pharmaceutical, potently inhibits the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine (and dopamine to a lesser extent), but rather than being developed for the already-crowded antidepressant market, it is being researched as a non-opioid, non-NSAID analgesic.

- SEP-227162 – An SNRI under development by Sepracor for the treatment of depression.

Indications

editSNRIs are approved for treatment of the following conditions:

- Major depressive disorder (MAD)

- Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

- Social anxiety disorder (SAD)

- Panic disorder

- Neuropathic pain

- Fibromyalgia

- Chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Pharmacology

editRoute of Administration

editSNRIs are delivered orally, usually in the form of gel capsules. The drugs themselves are usually a fine crystalline powder which diffuses into the body during digestion.

Dosage

editDosages fluctuated depending on the SNRI used due to varying potencies of the drug in question as well as multiple strengths for each drug.

Mode of Action

editThe disease for which SNRIs are mostly indicated, Major Depressive Disorder, is thought to be mainly caused by decreased levels of serotonin and norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft, causing erratic signaling. Due to the monoamine hypothesis of depression, which asserts that decreased concentrations of monoamine neurotransmitters leads to depression symptoms, the following relations were determined: "Norepinephrine may be related to alertness and energy as well as anxiety, attention, and interest in life; [lack of] serotonin to anxiety, obsessions, and compulsions; and dopamine to attention, motivation, pleasure, and reward, as well as interest in life."[6] SNRIs work by inhibiting the reuptake of the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine. This results in an increase in the extracellular concentrations of serotonin and norepinephrine and, therefore, an increase in neurotransmission. Most SNRIs including venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine, are several fold more selective for serotonin over norepinephrine, while milnacipran is three times more selective for norepinephrine than serotonin. Elevation of norepinephrine levels is thought to be necessary for an antidepressant to be effective against neuropathic pain, a property shared with the older tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), but not with the SSRIs.[7]

Recent studies have shown that depression may be linked to increased inflammatory response[8], thus attempts at finding an additional mechanism for SNRIs have been made. Studies have shown that SNRIs as well as SSRIs have significant anti-inflammatory action on microglia[9] in addition to their effect on serotonin and norepinephrine levels. As such, it is possible that an additional mechanism of these drugs exists which acts in combination with the previously understood mechanism. The implication behind these findings suggests use of SNRIs as potential anti-inflammatories following brain injury or any other disease where swelling of the brain is an issue. It should be noted, however, that regardless of the mechanism, the efficacy of these drugs in treating the diseases for which they have been indicated has been proven, both clinically and in practice.

Pharmacodynamics

editMost SNRIs function alongside primary metabolites and secondary metabolites in order to inhibit reuptake of serotonin, norepinepherine, and trace amounts of dopamine. For example, venlafaxine works alongside its primary metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine to strongly inhibit serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in the brain while . Recent evidence suggests that dopamine and norepinepherine behave in a cotransportational manner, due to dopamine's inactivation by norepinephrine reuptake in the prefrontal cortex, which largely lacks dopamine transporters. Therefore, SNRIs can increase dopamine neurotransmission in this part of the brain.[10] Furthermore, because SNRIs are extremely selective, they have no measurable effects on unintended systems, such as on monoamine oxidase inhibition.[11] Furthermore, studies have shown that SNRIs as well as SSRIs have significant anti-inflammatory action on microglia[12][13][14][15][16][17]

Pharmacokinetics

editThe usual half-life of SNRIs is 5 hours, with patients reaching peak effectiveness ~4 hours post ingestion.[13] [14][15][16][17]

Contraindications

editDue to the effects of increased norepinephrine levels and therefore higher adrenergic activity, pre-existing hypertension should be controlled before treatment with SNRIs and blood pressure periodically monitored throughout treatment. Duloxetine has also been associated with cases of hepatic failure and should not be prescribed to patients with chronic alcohol use or liver disease. Patients who are suffering from coronary artery disease should avoid the use of SNRIs. Furthermore, due to some SNRIs' actions on obesity, patients with major eating orders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia should not be prescribed SNRIs.[13] Duloxetine and milnacipran are also contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled narrow-angle glaucoma, as they have been shown to increase incidence of mydriasis.[16][17]

SNRIs should be taken with caution when using St John's wort as the combination can lead to the potentially fatal serotonin syndrome.[18] There is also a significant risk when combining SNRIs with dextromethorphan, tramadol, cyclobenzaprine, meperidine/pethidine, and propoxyphene. They should never be taken within 14 days of any other antidepressant, especially with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), as combinations of SNRIs with MAOIs can cause hyperthermia, rigidity, myoclonus, autonomic instability with fluctuating vital signs, and mental status changes that include extreme agitation progressing to delirium and coma.[16]

Side-effects

editBecause the SNRIs and SSRIs both act similarly to elevate serotonin levels, they subsequently share many of the same side-effects, though to varying degrees. The most common include loss of appetite, weight, and sleep. There may also be drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, headache, increase in suicidal thoughts, mydriasis, nausea/vomiting, sexual dysfunction, and urinary retention. There are two common sexual side-effects: diminished interest in sex (libido) and difficulty reaching climax (anorgasmia), which are usually somewhat milder with the SNRIs in comparison to the SSRIs. Elevation of norepinephrine levels can sometimes cause anxiety, mildly elevated pulse, and elevated blood pressure. People at risk for hypertension and heart disease should have their blood pressure monitored.[13] [14][15][16][17]

Precautions

editStarting an SNRI regimen

editDue to the extreme changes in adrenergic activity produced from norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibition, patients that are just starting an SNRI regimen are usually given lower doses than their expected final dosing to allow the body to acclimate to the drug's effects. As the patient continues along at low doses without any side effects, the dose is incrementally increased until the patient sees improvement in symptoms without detrimental side effects.[19]

Discontinuation syndrome

editAs with SSRIs, the abrupt discontinuation of an SNRI usually leads to withdrawal, or "discontinuation syndrome", which could include states of anxiety and other symptoms. It is therefore recommended that users seeking to discontinue an SNRI slowly taper the dose under the supervision of a professional. Discontinuation syndrome has been reported to be markedly worse for venlafaxine when compared to other SNRIs. Accordingly, as tramadol is related to venlafaxine, the same conditions apply.[20] This is likely due to venlafaxine's relatively short half-life and therefore rapid clearance upon discontinuation.

Overdose

editCauses

editOverdosing on SNRIs can be caused by either drug combinations or excessive amounts of the drug itself. These overdoses are extremely dangerous and potentially fatal.[13] [14][15][16][17]

Symptoms

editSymptoms of SNRI overdose, whether it be a mixed drug interaction or the drug alone, vary in intensity and incidence based on the amount of medicine taken and the individuals sensitivity to SNRI treatment. Possible symptoms are as follows[16]:

Management

editOverdose is usually treated symptomatically, especially in the case of serotonin syndrome, which requires treatment with cryoheptadine and temperature control based on the progression of the serotonin toxicity. Patients are often monitored for vitals and airways cleared to ensure that they are receiving adequate levels of oxygen. Another option is to use activated carbon in the GI tract in order to adsorb excess neurotransmitter.[16] It is important to consider drug interactions when dealing with overdose patients, as separate symptoms can arise.

Comparison to SSRIs

editThe SNRIs were developed more recently than the SSRIs[date missing] and as a result there are relatively few of them. However, the SNRIs are among the most widely used antidepressants today. In 2009, Cymbalta and Effexor were the 11th- and 12th-most-prescribed branded drugs in the United States. This translates to the 2nd- and 3rd-most-common antidepressants, behind Lexapro (#5), the SSRI escitalopram.[21] In some studies, SNRIs demonstrated slightly higher antidepressant efficacy than the SSRIs (response rates 63.6% versus 59.3%).[22] However, in one study escitalopram had a superior efficacy profile to venlafaxine.[23] It is not clear what the reasons were for this unexpected anomaly. The side-effects of SNRIs are reported to be slightly less severe in comparison to the SSRIs as well.[citation needed] One of the major complaints that many users of SSRIs have is the negative sexual side-effects that can be very difficult to treat.[2] Although SNRIs can have similar side-effects, many of them can have the opposite effect of increased libido. Wellbutrin has had official studies done,[3] and Strattera and Savella have commonly been reported as increasing libido in both men and women, even though studies have contradicted these reports.[4] However, the individuals who reported increased sexual functioning also tended to report increased anxiety, heart rate, blood pressure, and other negative effects associated with adrenaline increase.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ http://www.emedexpert.com/facts/venlafaxine-facts.shtml

- ^ Deecher DC, Beyer CE, Johnston G; et al. (August 2006). "Desvenlafaxine succinate: A new serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 318 (2): 657–65. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.103382. PMID 16675639.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iyengar S, Webster AA, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Xu JY, Simmons RM (November 2004). "Efficacy of duloxetine, a potent and balanced serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in persistent pain models in rats". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 311 (2): 576–84. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.070656. PMID 15254142.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rxlist.com: "Nefazodone Prescribing Information", accessed 24 May 2012.]

- ^ Nonogaki K, Nozue K, Kuboki T, Oka Y (May 2007). "Milnacipran, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, induces appetite-suppressing effects without inducing hypothalamic stress responses in mice". Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 292 (5): R1775–81. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00527.2006. PMID 17218444.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nutt DJ. Relationship of neurotransmitters to the symptoms of major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69 Suppl E1:4–7. PMID 18494537.

- ^ Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS (2005). "Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain". Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 96 (6): 399–409. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_96696601.x. PMID 15910402.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shelton RC, Miller AH (2011). "Inflammation in depression: is adiposity a cause?". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 13 (1): 41–53. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/rshelton. PMC 3181969. PMID 21485745.

- ^ Tynan RJ, Weidenhofer J, Hinwood M, Cairns MJ, Day TA, Walker FR (2012). "A comparative examination of the anti-inflammatory effects of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants on LPS stimulated microglia". Brain Behav Immun. 26 (3): 469–479. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2011.12.011. PMID 22251606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://stahlonline.cambridge.org/prescribers_drug.jsf?page=0521683505c95_p539-544.html.therapeutics&name=Venlafaxine&title=Therapeutics

- ^ Lambert O, Bourin M (2002). "ISNRIs: mechanism of action and clinical features". Neurobiology of Anxiety and Depression. 2 (6): 849–858. doi:10.1586/14737175.2.6.849. PMID 19810918.

- ^ Tynan RJ, Weidenhofer J, Hinwood M, Cairns MJ, Day TA, Walker FR (2012). "A comparative examination of the anti-inflammatory effects of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants on LPS stimulated microglia". Brain Behav Immun. 26 (3): 469–479. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2011.12.011. PMID 22251606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Meridia Prescription Information" (PDF). Abbott Labrotories. August 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Pristiq Prescription Information". Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. April 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Effexor XR Prescription Information". Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. November 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Cymbalta Prescription Information" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. September 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Savella Prescription Information" (PDF). Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc. December 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Karch, Amy (2006). 2006 Lippincott's Nursing Drug Guide. Philadephia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 1-58255-436-6.

- ^ {{cite web |url= http://www.uptodate.com/contents/duloxetine-drug-information?source=search_result&search=snri&selectedTitle=3~150%7Ctitle=Duloxetine: Drug Information|publisher=UpToDate|accessdate=28 June 2012}

- ^ Perahia DG, Pritchett YL, Kajdasz DK, Bauer M, Jain R, Russell JM, Walker DJ, Spencer KA, Froud DM, Raskin J, Thase ME. (2008). "A randomized, double-blind comparison of duloxetine and venlafaxine in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder". J Psychiatr Res. 42 (1): 22–34. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.008. PMID 17445831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "2009 Top 200 branded drugs by total prescriptions" (PDF). SDI/Verispan, VONA, full year 2009. www.drugtopics.com. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ Papakostas, G.; Thase, M.; Fava, M.; Nelson, J.; Shelton, R. (2007). "Are antidepressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (11): 1217–1227. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027. PMID 17588546.

- ^ Llorca, P. M.; Fernandez, J. -L. (2007). "Escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder: clinical efficacy, tolerability and cost-effectiveness vs. Venlafaxine extended-release formulation". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 61 (4): 702–710. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01335.x. PMID 17394446.

Category:Monoamine reuptake inhibitors Category:Drugs acting on the nervous system