On 2 October 2018, Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi dissident journalist, was killed by agents of the Saudi government at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey.[4][5] Khashoggi was ambushed and strangled by a 15-member squad of Saudi operatives.[6][7] His body was dismembered and disposed of in some way that was never publicly revealed.[8] The consulate had been secretly bugged by the Turkish government and Khashoggi's final moments were captured in audio recordings, transcripts of which were subsequently made public.[9][6][10]

| Assassination of Jamal Khashoggi | |

|---|---|

Jamal Khashoggi in March 2018 | |

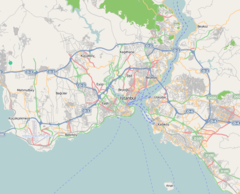

Location of the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, where the assassination took place[1] | |

| Location | Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey |

| Coordinates | 41°05′10″N 29°00′44″E / 41.0860°N 29.0121°E |

| Date | 2 October 2018 Some time after 1 p.m. (TRT), when Khashoggi entered the Saudi consulate[1][2] |

| Victim | Jamal Khashoggi |

| Motive | Allegedly to remove a prominent dissident and critic of the Saudi government[1][3] |

| Convicted | For murder: Fahad Shabib Albalawi Turki Muserref Alshehri Waleed Abdullah Alshehri Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb Salah Mohammed Tubaigy |

| Verdict | Death for murder: five persons Imprisonment for cover-up of the murder: three other persons |

The New York Times reported in June 2019 that Saudi government engaged in an extensive effort to cover up the killing, including destroying evidence.[7] By 16 October, separate investigations by Turkish officials and The New York Times had concluded that the murder was premeditated and that some members of the Saudi hit team were closely connected to Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia.[11]

After repeatedly shifting its account of what happened to Khashoggi in the days following the killing, the Saudi government admitted on 25 October that he had been killed in a premeditated murder,[12][13] but denied that the killing took place on the orders of bin Salman.[12][14][15] Bin Salman said he accepted responsibility for the killing "because it happened under my watch" but asserted that he did not order it.[6]

By November 2018, the US Central Intelligence Agency had concluded that bin Salman had ordered the murder.[1] In the same month, the United States levelled sanctions against 17 Saudis over the murder, but did not sanction bin Salman himself.[16] President Donald Trump disputed the CIA assessment, expressed support for bin Salman, and stated that the investigation into Khashoggi's death had to continue.[17]

The murder prompted intense global scrutiny and criticism of the Saudi government.[18] A report by the United Nations special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions in June 2019 concluded that Khashoggi's murder was premeditated and called for a criminal investigation by the UN and, because Khashoggi was a resident of the United States, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation.[7][18] Saudi prosecutors rejected the findings of the UN investigation and again asserted that the killing was not premeditated.[18]

In January 2019, trials began in Saudi Arabia against 11 Saudis accused of involvement in Khashoggi's murder.[19][18] In December 2019, following secretive proceedings, three defendants were acquitted; five were sentenced to death; and three others were sentenced to prison.[18] Two of the acquitted defendants, Saud al-Qahtani and Ahmed al-Asiri, were high-level Saudi security officials. The five men sentenced to death were low-level participants and were pardoned in May 2020 by Khashoggi's children.[18][20] The results of the trial were criticized by Agnès Callamard, then-UN Special Rapporteur who investigated the murder.[18]

Jamal Khashoggi

editKhashoggi was a Saudi journalist,[5] author, and a former general manager and editor-in-chief of Al-Arab News Channel.[21] He also served as editor for the Saudi newspaper Al Watan, turning it into a platform for Saudi progressives.[22]

Khashoggi fled Saudi Arabia in June 2017 and went into self-imposed exile in the US. He began to contribute columns to the global opinions section of The Washington Post in September 2017. His work was often critical of the Saudi government and the Saudi royal family, especially Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and he advocated for reform in the country.[23][5] He opposed the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen.[24]

After Khashoggi started writing for The Washington Post, he was harassed via Twitter from pro-regime trolls and bot accounts.[23] It is believed that his harassment was instigated by Saudi royal adviser Saud al-Qahtani, who had been tasked by Prince bin Salman with implementing a zero-tolerance crackdown on dissent on social media. Qahtani was later implicated in Khashoggi's murder.[25][26]

Just before he was murdered, Khashoggi launched several projects to consolidate opposition to the Saudi regime, counter regime propaganda, and press for reform. One major collaborator was Saudi dissident blogger Omar Abdulaziz, one of the most visible public critics of the Saudi regime abroad.[27] In late September 2018, Khashoggi met with friends in London to discuss his various plans.[28] Khashoggi wrote in his last column, posthumously published, that "what the Arab world needs most is free expression".[29][30]

Pegasus spyware phone hack

editIn summer 2018, Abdulaziz's cell phone was infected with a surveillance tool. This was first revealed on 1 October 2018 in a detailed forensic report by Citizen Lab,[31] a University of Toronto project that investigates digital espionage against civil society. Citizen Lab concluded with a "high degree of confidence" that his cellphone was successfully targeted with NSO Group's Pegasus spyware and attributed this infection to an operator linked to "Saudi Arabia's government and security services".[31] NSO's Pegasus, of which Saudi Arabia has emerged as one of its biggest operators, is one of the most advanced spyware tools available. It is designed to infect cell phones without being detected. Among other known cases, Saudi Arabia is believed to have used NSO software to target London-based Saudi dissident Yahya Assiri, a former Royal Saudi Air Force officer, founder of the human rights organisation ALQST and an Amnesty International researcher.[32][33]

Through their sophisticated spyware attack on Abdulaziz's phone, the Saudi regime would have had a direct line into Khashoggi's private thoughts, and access to hours of conversations between the two men. Abdulaziz recalled: "Jamal was very polite in public, but in private, he spoke more freely – he was very very critical of the crown prince."[34]

On 21 September, eleven days before Khashoggi was murdered in the Saudi consulate, he made a declaration of support for The Bees Army. Using the Bee Army's first hashtag "what do you know about bees" he tweeted, "They love their home country and defend it with truth and rights".[35]

On 9 October, one week after his disappearance, The Washington Post published an article in which Hatice Cengiz, Khashoggi's fiancée, claimed that he had applied for U.S. citizenship.[36]

On 19 October, the Wilson Center issued a statement saying that they had offered him a fellowship at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (or Wilson Center), located in Washington, D.C.[37][38]

On 22 October, Marc Owen Jones, an assistant professor at Hamad Bin Khalifa University in Doha who researched Arab propaganda and has monitored Saudi Twitter bots for two years, said he had seen a massive surge in pro-regime Twitter activity, and in the creation of troll accounts, since Khashoggi went missing: "There was such a huge spike in October in bot accounts and the use of the hashtags praising the crown prince, it's absurd".[35]

After Khashoggi's murder, the Saudi cyber-operations were the focus of global scrutiny. The Government of Canada started an investigation in to those malicious cyberattacks.[39]

In December 2018 Omar Abdulaziz granted CNN access to his text messages with Khashoggi, where the two discussed their sharp criticism and political opposition to Mohammed bin Salman.[40][41] Abdulaziz filed a lawsuit against an Israeli company, NSO Group Technologies, that allowed his smartphone to be taken over and his communications to be spied on by the Saudi regime.[42]

U.S. intelligence reports

editThe Washington Post reported on 10 October 2018 that U.S. intelligence intercepted communications of Saudi officials discussing a plan ordered by the Crown Prince Bin Salman, to capture Khashoggi from his home in Virginia.[43][44] The intercepted communications were regarded as significant because Khashoggi had bought a home in McLean, Virginia,[45] where he lived after fleeing Saudi Arabia. Khashoggi had obtained an O visa – also known as the "genius" visa, that offers individuals of "extraordinary ability and achievement" in the sciences, arts, education, and other fields and are recognized internationally – he had applied for permanent residency status, and three of his children were US citizens.[46][47] As a legal resident of the United States Khashoggi was entitled to protection. Under a directive adopted in 2015, the US intelligence community has a "duty to warn" people – including those who are not US citizens – who are at risk of being kidnapped or killed. This directive was a central aspect of the conversation about the US's response to Khashoggi's disappearance.

According to National Security Agency (NSA) officials, the White House was warned of this threat through official intelligence channels.[48] Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats declined to comment on why Khashoggi was not warned.[47] 55 members of Congress demanded in a letter clarity from DNI Dan Coats on what the intelligence community knew about the risk Khashoggi faced before his disappearance and whether American officials attempted to notify him that his life was in danger. In the letter, they sought insight into everything the NSA knows about phone calls and emails from Saudi officials on the Khashoggi case.[49]

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University filed a lawsuit against five US intelligence services "seeking immediate release of records concerning U.S. intelligence agencies' compliance or non-compliance with their 'duty to warn' reporter Jamal Khashoggi of threats to his life or liberty". The Committee to Protect Journalists joined the legal effort.[50][51]

On 16 November, Central Intelligence Agency employees who internally analyzed multiple sources of intelligence concluded that Mohammed bin Salman ordered Khashoggi's assassination.[1] On 20 November, US President Donald Trump disputed the CIA assessment and stated that the investigation into Khashoggi's death had to continue.[17] The 2020 National Defense Authorization Act required the U.S. intelligence community to share the report on who was responsible for Khashoggi's murder, but the Trump administration refused to release the report.[52][53]

Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines declassified a four-page report on 25 February 2021 and released it the next day,[54] as she had promised to do even before the Biden administration began. As expected, the report blamed Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman for the murder, which had been the ultimate conclusion of the CIA.[52] Shortly after publication of the report it was replaced by an updated version,[55] from which three names were removed.[56] Following the report, the US announced sanctions on several Saudis involved in the killing, but not on Mohammed bin Salman.[57] Some exiled Saudi dissidents said "they have been put in greater danger" due to the lack of sanctions against Mohammed bin Salman.[58]

Disappearance

editOver the course of 2017, the House of Saud appealed to Khashoggi to return to Riyadh and resume his services as a media advisor to the royal court. But he declined in fear that it was a ruse and that upon returning he would be imprisoned or worse. Khashoggi met with crown prince Mohammed's brother Prince Khalid at the Saudi embassy in Washington, in "early 2018 or late 2017."[59] In September 2018 Khashoggi visited the Washington embassy again, to retrieve paperwork for his pending marriage to his Turkish fiancée, Hatice Cengiz. He tried to complete everything in the U.S. but was instead lured to the Saudi Arabian consulate in Turkey, where his fiancée lived.[60][61]

Khashoggi's first visit to the Saudi consulate in Istanbul was on 28 September 2018 – where he showed up unannounced. Having divorced his wife, who had remained in Saudi Arabia, he went to the consulate to obtain a document certifying that he was no longer married so he could marry his Turkish fiancée. Before that visit he "sought assurances about his safety from friends in the US" and instructed his fiancée to contact Turkish authorities if he failed to emerge.[62] He received a warm welcome from officials, and was told to return to the consulate on 2 October. "He was very pleased with their nice treatment and hospitality", she later said.[63] On 29 September Khashoggi traveled to London and spoke at a conference. On 1 October Khashoggi returned to Istanbul, and he told a friend that he was worried about being kidnapped and sent back to Saudi Arabia.[64]

Meanwhile, at around 16:30, a three-person Saudi team arrived in Istanbul on a scheduled flight, checked in to their hotels then visited the consulate, according to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Another group of officials from the consulate traveled to a forest in Istanbul's outskirts and the nearby city of Yalova on a "reconnaissance" trip. Erdogan said a "road map" to kill Khashoggi was devised in Saudi Arabia during this time. In the night of 2 October, a 15-member group arrived from Riyadh on two private Gulfstream jets.[65]

On 2 October 2018 CCTV showed the suspected agents entering the consulate around noon. Khashoggi arrived about an hour later, accompanied by his fiancée Cengiz, whom he entrusted with two cell phones while she waited outside for him.[64][66][67] He entered the consulate, through the main entrance, at 1:14 pm.[2] As he had not come out by 4 pm, even though the working hours of the consulate were until 3:30 pm,[68] Cengiz contacted the authorities, phoning Khashoggi's friend, Yasin Aktay, an adviser to Erdogan,[69] reported him missing and the police then started an investigation.

The Saudi government said that he had left the consulate[70][71][72] via a back entrance.[73] The Turkish government first said that he was still inside, and his fiancée and friends said that he was missing.[64]

Turkish authorities have claimed that security camera footage of the day of the incident was removed from the consulate and that Turkish consulate staff were abruptly told to take a holiday on the day Khashoggi disappeared while inside the building.[74] Turkish police investigators told the media that the recordings from the security cameras did not show any evidence of Khashoggi leaving the consulate.[75] A security camera was located outside the consulate's front which showed him entering but not leaving, while another camera installed at a preschool opposite the rear entrance of the consulate also did not show him leaving.[75]

The disappearance presented Turkish officials with a sharp diplomatic challenge. Journalist Jamal Elshayyal reported Turkish authorities were trying to walk a fine line so as not to damage the Turkish-Saudi relationship: "There is an attempt by the Turkish government to try to find a way out of this whereby there isn't a full collapse of diplomatic relations, at least a temporary freeze between Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Because, if indeed, Turkish authorities can prove unequivocally that Saudi agents essentially murdered a journalist inside the consulate in Istanbul, it would require some sort of strong reaction."[66] Analysts have suggested that Khashoggi may have been considered especially dangerous by the Saudi leadership not because he was a long-time dissident, but rather, a pillar of the Saudi establishment who had been close to its ruling circles for decades, had worked as an editor at Saudi news outlets and had been an adviser to a former Saudi intelligence chief Turki bin Faisal Al Saud.[3]

Assassination

editAccording to numerous anonymous police sources, Turkish police believe that Khashoggi was tortured and killed inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul[76][77] by a 15-member team brought in from Saudi Arabia for the operation.[78][79] One such source claimed the dead body was dismembered, and that the entire assassination had been recorded by the killers on a videotape taken out of Turkey afterwards.[77] Middle East Eye cited an anonymous Saudi who said the Tiger Squad brought Khashoggi's fingers to Mohammed bin Salman in Riyadh as other evidence that the mission was successful.[80]

On 7 October, Turkish officials pledged to release evidence showing that Khashoggi was killed.[79] Aktay initially said he believed Khashoggi had been killed in the consulate,[77] but on 10 October he claimed that "the Saudi state is not blamed here", something that a journalist for The Guardian saw as Turkey trying not to harm lucrative trade ties and a delicate regional relationship with Saudi Arabia.[74] Turkey then claimed to have audio and video evidence of the killing occurring inside the consulate.[81] U.S. President Donald Trump said the United States had asked Turkey for the recordings.[82] According to "people familiar with the matter", the audio was shared with Central Intelligence Agency agents; a CIA spokeswoman declined to comment.[83]

CNN reported on 15 October that Saudi Arabia was about to admit to the killing, but would claim that it was an interrogation that went wrong.[84] This claim drew criticism from some, considering that Khashoggi was reportedly dismembered and that his killing was allegedly premeditated, and the circumstances, including the arrival and departure of a team of 15 people, including forensic specialists presumed to have been present to hide evidence of the crime, on the same day.[84] Those men had flown on two private jets owned by Sky Prime Aviation, a company controlled by Mohammed bin Salman since its transfer to Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund the previous year.[85]

The next day, Middle East Eye reported that, according to an anonymous Turkish source, the killing took about seven minutes and forensic specialist Salah Muhammed al-Tubaigy, who had brought along a bone saw,[86] cut Khashoggi's body into pieces, while Khashoggi was still alive, as he and his colleagues listened to music.[87] The source further claimed, "Khashoggi was dragged from consul general Mohammad al-Otaibi's office at the Saudi consulate ... Tubaigy began to cut Khashoggi's body up on a table in the study while he was still alive," and, "There was no attempt to interrogate him. They had come to kill him."[86]

Reuters reported that al-Otaibi left Istanbul for Riyadh on 16 October. His departure came hours before his home was expected to be searched in relation to the journalist's disappearance.[88] The Wall Street Journal published reports from anonymous sources that Khashoggi was tortured in front of top Saudi diplomat Mohammad al-Otaibi, Saudi Arabia's consul general.[89][90] The Turkish pro-government newspaper Daily Sabah reported on 18 October that neighbours of the consul's residence had observed an unusual barbecue party, which the paper suggested might have been to mask the smell from the incineration of the dismembered corpse: "We have been living here for twelve years but I have never seen them having a barbecue party. That day, they had a barbecue party in the garden."[91]

On 20 October, the Saudi Foreign Ministry reported that a preliminary investigation showed that Khashoggi had died at the consulate while engaged in a fight, the first Saudi acknowledgement of Khashoggi's death.[92] It was also announced that Saud al-Qahtani and Ahmad Asiri had been fired by the Saudi royal court for involvement in Khashoggi's killing.[93] The following day, an anonymous Saudi official said Khashoggi had been threatened with drugging and kidnapping by Maher Mutreb, had resisted and was restrained with a chokehold, which killed him.[94]

On 22 October, Reuters cited a Turkish intelligence source and a high-ranking Arab with access to intelligence and links to members of Saudi's royal court and reported that Saud al-Qahtani, the then-top aide for Mohammed bin Salman, had made a Skype call to the consulate while Khashoggi was held in the room. Qahtani reportedly insulted Khashoggi, who responded in kind. According to the Turkish source, Qahtani then asked the team to kill Khashoggi. Qahtani instructed: "Bring me the head of the dog". According to both sources, the audio of the Skype call was given to Erdogan.[25]

According to Nazif Karaman of the Daily Sabah, the audio recording from inside the consulate revealed that Khashoggi's last words were: "I'm suffocating... take this bag off my head, I'm claustrophobic."[95] On 10 December, the details of the transcript of the audio were described to CNN by an anonymous source.[96]

On 16 November, a Hürriyet columnist reported that Turkey has more evidence, including a second audio recording from the consulate, where the Saudi team reviews the plans on how to execute Khashoggi. He also reported, "Turkish officials also did not confirm [the Saudi prosecutor's claim] that Khashoggi was killed after they gave him a fatal dose of a drug. They say that he was strangled with a rope or something like a plastic bag."[97]

Investigation

editHatice Cengiz begged the US government to take action in helping to find her fiancé. In her 9 October op-ed in The Washington Post, Cengiz wrote, "At this time, I implore President Trump and first lady Melania Trump to help shed light on Jamal's disappearance. I also urge Saudi Arabia, especially King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, to show the same level of sensitivity and release CCTV footage from the consulate."[36]

Sabah reported on 11 October that Turkish officials were investigating whether Khashoggi's Apple Watch would reveal clues as to what happened to him inside the Saudi consulate, examining whether data from the smartwatch could have been transmitted to the cloud, or his personal phone, which was with Cengiz.[98]

On the evening of 14 October, President Erdoğan and King Salman announced that a deal had been made for a "jointing working group" to examine the case.[99] On 15 October the Turkish Foreign Ministry announced that an "inspection" of the consulate, by both Turkish and Saudi officials, would take place that afternoon.[100][101] According to an anonymous source from the Attorney General's office, Turkish officials found evidence of "tampering" during the inspection, and evidence that supports the belief Khashoggi was killed.[102] President Erdoğan said that "investigation is looking into many things such as toxic materials and those materials being removed by painting them over".[103]

According to anonymous sources, Turkish police have expanded the search, as Khashoggi's body may have been disposed of in nearby Belgrad Forest or on farmland in Yalova Province, as indicated by the movement of the Saudi vehicles,[104] and DNA tests of samples from the Saudi consulate and the consul's residence were being conducted in 2018;[105] Al Jazeera reported that according to anonymous sources, fingerprints of one of the alleged perpetrators, Salah Muhammad al-Tubaigy, were found in the consulate.[106]

Confirmation of death

editOn 20 October, the Saudi Foreign Ministry reported that a preliminary investigation showed that Khashoggi had died at the consulate while engaged in a fight, the first Saudi acknowledgement of Khashoggi's death.[92]

On 22 October, six US and Western officials[107] stated they believed that the crown prince Mohammad bin Salman, because of his role overseeing the Saudi security apparatus, was ultimately responsible for Khashoggi's disappearance, and the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Gina Haspel, departed for Turkey to work on the investigation[108] "amid a growing international uproar over Saudi's explanation of the killing".[109] The Governor of İstanbul's office said that Khashoggi's fiancée, Hatice Cengiz, had been given 24-hour police protection.[110]

Also on 22 October, CNN aired CCTV law enforcement footage from the Turkish authorities, showing the Saudi agent Mustafa al-Madani, a member of the 15-man team, leaving the consulate by the back door.[111] He was dressed up in Khashoggi's clothes, except for the shoes. Madani had also put on a fake beard that resembled Khashoggi's facial hair, his glasses and his Apple Watch.[112][94][113] Madani, who was of similar age, height, and build to Khashoggi, left the consulate from its back door.[111] He was later seen at Istanbul's Blue Mosque, where he went to a public bathroom and changed back to his own clothes and discarded Khashoggi's clothes.[111] Later he was seen dining with another Saudi agent, and the footage shows him smiling and laughing.[114] An anonymous Turkish official believes that Madani was brought to Istanbul to act as a body double and that "You don't need a body double for a rendition or an interrogation. Our assessment has not changed since October 6. This was a premeditated murder, and the body was moved out of the consulate."[111] The use of the body double might have been an attempt to lend credence to the Saudi government's first version of events: that Khashoggi walked out through the back not long after he arrived. But "it was a flawed body double, so it never became an official part of the Saudi government's narrative", a Turkish diplomat told The Washington Post.[115]

The body double footage bolstered Turkish claims that the Saudis always intended either to kill Khashoggi or move him back to Saudi Arabia. Ömer Çelik, a spokesman for Turkey's ruling AKP, stated: "We are facing a situation that has been monstrously planned and later tried to be covered up. It is a complicated murder."[116]

Saudi Arabia has vowed it will conduct a thorough criminal investigation and deliver justice for Khashoggi, Turkish investigators have been faced with several delays from their Saudi counterparts. On 22 October, BBC reported that Turkish police had found a car "belonging to the consulate" abandoned in an underground car park in Istanbul. Permission was sought from the Saudi diplomats to search the car.[13] Turkish media published a video from 3 October (the day after the disappearance) that apparently showed the staff of the consulate burning documents.[13]

Search of Saudi consul's residence

editOn Sunday 7 October, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs summoned Saudi Arabian Ambassador Waleed A. M. Elkhereiji to demand for the second time permission to search the consulate building.[117] Saudi officials continued to refuse that Turkish police could search the well in the Saudi consul's garden,[118][119] but granted permission on 24 October (22 days after the assassination).[120][121][122] Turkish newspaper Hürriyet reported on 26 October that police had found no DNA traces of Khashoggi in water samples taken from the well.[123][124]

Calling for an international investigation, at the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City on 25 October, Agnès Callamard, UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, explained the Saudi officials implicated in the death of Khashoggi "are high enough to represent the state".[125] "Even Saudi Arabia has admitted that the crime was premeditated ... From where I sit, this bears all the hallmarks of extrajudicial executions. Until I am proven otherwise I must assume that this was the case. It is up to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to prove that it was not."[126]

Saudi public prosecutor visits Turkey

editSaudi public prosecutor Saud al-Mojeb arrived in Istanbul on 28 October, days after he contradicted weeks of official Saudi statements by saying that Khashoggi's murder was premeditated. His trip came amid Turkish suggestions that the Saudis were not cooperating and had attempted to tamper with evidence.[127] Mojeb held talks on 29 October with Istanbul's chief prosecutor Irfan Fidan at the Çağlayan courthouse. Saudi officials asked the Turkish prosecutor to hand over all of their evidence, including video footage. Turkish investigators offered a 150-page dossier that summarized their findings, but refused to hand over the complete investigative file.[128][129] Although Saudi foreign minister Adel al-Jubeir had stated on 27 October that the suspects would be tried on Saudi soil, Turkish officials presented an extradition request for the 18 suspects to be brought to Turkey for trial.[128][129] They also pressed for information about Khashoggi's body, its disposal, and the progress of the Saudi investigation. The tense meeting only lasted 75 minutes.[128][129]

Mojeb held a second round of talks with Fidan on 30 October, before inspecting the Saudi consulate in the Levent neighbourhood, where he left after spending a little over an hour.[130][131] According to a source at the prosecutor's office, Fidan asked Mojeb to conduct another joint search at the consul-general's residence, because when Turkish investigators first entered the building in mid-October they were not allowed to search three locked rooms and were also not allowed to search a 20-metre (66 ft)-deep well. The Saudis did not let firefighters descend into the well, and the search ended with police only able to obtain some water samples.[127]

The following day, President Erdoğan repeated the demand for the suspects to be extradited to Turkey for trial.[131] He accused the Saudi prosecutor of refusing to cooperate during his visit. A source reported that Mojeb provided no information to Turkish investigators, but wanted to take Khashoggi's mobile phones, which had been left outside the consulate with Khashoggi's fiancée.[132]

Body disposal and alleged evidence tampering

editOn 31 October a senior Turkish official told The Washington Post that Turkish authorities were investigating the theory that Khashoggi's body was destroyed in acid on the grounds of the consulate or at the nearby residence of the Saudi consul general. The "biological evidence" discovered in the consulate garden supported the theory.[133] Echoing the claim, Yasin Aktay, an adviser to Erdoğan in his ruling AK Party and a friend of Khashoggi, hinted in an article in the Turkish newspaper Hürriyet, published on 2 November, that the body was destroyed by dismembering and dissolving in acid: "We now see that it wasn't just cut up, they got rid of the body by dissolving it".[134][135][136]

On 4 March 2019, Al Jazeera Arabic released a documentary on the investigation of Khashoggi's murder and the subsequent coverup. In its coverage, the network states that the body was likely disposed of by being cremated in a recently constructed extra large oven at the Saudi consulate general's residence, which Al Jazeera suggested was likely purpose built for the disposal of Khashoggi's remains. An interview with the oven's builder revealed that it was designed to be "deep", and capable of withstanding temperatures over 1,000 °C (1,830 °F). The burning reportedly took three days and happened in parts. Afterwards, a large quantity of barbecue meat was prepared to cover the evidence of cremation.[137][138]

In an op-ed in The Washington Post, Erdoğan described the murder as "inexplicable" and as a "clear violation and a blatant abuse of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations", arguing that not punishing the perpetrators "could set a very dangerous precedent." He criticised Saudi inaction against the consul general Mohammad al-Otaibi, who had misled the media and had fled the country shortly afterwards. He warned that no-one should dare commit "such acts on the soil of a NATO ally again" and wrote: "As responsible members of the international community, we must reveal the identities of the puppet masters behind Khashoggi's killing and discover those in whom Saudi officials – still trying to cover up the murder – have placed their trust... We know that the order to kill Khashoggi came from the highest levels of the Saudi government." He urged the international community to uncover the whole truth.[139]

On 5 November, Daily Sabah quoted a Turkish official who said that an 11-member team, including chemist Ahmad Abdulaziz Aljanobi and toxicology expert Khaled Yahya al-Zahrani, had been sent by Saudi Arabia to Istanbul on 11 October to destroy the evidence.[140][141] The official suggested that this cover-up attempt indicated that Saudi officials were aware of the crime.[132] The Saudi team had visited the consulate every day between 11 and 17 October; Turkish officials were not permitted to search the consulate until 15 October.[141]

Audio tapes

editDuring a televised speech on 10 November, Erdoğan acknowledged the existence of multiple audio recordings relating to the killing, stating that Turkey had provided them to Saudi Arabia, the United States, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom.[132] These recordings document Khashoggi's torture and death, as well as conversations from before the incident, which led Turkey to conclude early on that the killing was premeditated. Saudi royal advisor Saud al-Qahtani was reported as having a major role throughout the recordings.[132]

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau confirmed that Turkey had shared audio of the killing with world governments, including Canada.[142][143] The German government confirmed it had received information from the Turkish authorities, but declined to elaborate.[144] In contrast, French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian denied receiving the audio.[144] British Foreign Secretary Jeremy Hunt paid an official visit to KSA and called for its cooperation with a "credible" investigation into Khashoggi's killing.[145]

While attending World War I centennial commemorations in France, Erdoğan and President Trump discussed how to respond to the killing, and later met with Secretary-General António Guterres of the United Nations.[146] President Trump and French President Emmanuel Macron agreed that more details were needed from KSA on Khashoggi's murder. Accordingly, they also agreed that the case should not cause further destabilization in the Middle East; and the fallout from the Khashoggi affair could create a way forward to find a resolution to the ongoing War in Yemen.[147]

Charges

editOn 15 November 2018, the Saudi Prosecutor's Office stated that 11 Saudi nationals had been indicted and charged with murdering Khashoggi and that five of the individuals who were indicted would face the death penalty since it had been determined they were directly involved in "ordering and executing the crime". Prosecutors alleged that shortly after Khashoggi entered the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul he was bound and then injected with an overdose of a sedative that resulted in his death. The prosecutors also alleged that his body had been dismembered and removed from the consulate by five of those charged in the killing and given to a local collaborator for disposal. Saudi officials continued to deny that the Saudi Royal Family was involved in, ordered, or sanctioned the killing.[14][15]

On 16 November 2018, several news organizations including The New York Times and The Washington Post reported that the CIA was unequivocal in assessing with "high confidence" that the crown prince Mohammad bin Salman ordered Khashoggi's assassination. The agency examined multiple sources of intelligence, including an intercepted phone call that the crown prince's brother Khalid bin Salman – the then Saudi ambassador to the United States – had with Khashoggi. A conclusion that contradicted previous Saudi government claims that the crown prince was not involved. A CIA spokesman and both the White House and the US State Department declined to comment. The Saudis issued a denial.[1][148]

On 20 November 2018, Trump issued the statement "On Standing with Saudi Arabia"[149] and without citing further evidence he denied the CIA's conclusion: "Our intelligence agencies continue to assess all information, but it could very well be that the Crown Prince had knowledge of this tragic event – maybe he did and maybe he didn't!"[150][17][151] In a series of interviews President Trump said the crown prince denies his involvement "vehemently" and the CIA only has "feelings" and there is "no smoking gun" in the death.[152] The next day Hürriyet columnist Abdulkadir Selvi wrote that the "CIA holds 'smoking gun phone call' of Saudi Crown Prince on Khashoggi murder",[153] and that Gina Haspel, director of the Central Intelligence Agency, has possession of an intercepted phone call in which crown prince Mohammad gives an order to his brother Khalid "to silence Jamal Khashoggi as soon as possible". "The subsequent murder is the ultimate confirmation of this instruction."[154][155][156]

Citing the leaked CIA assessment, The Wall Street Journal reported that Mohammed bin Salman sent at least 11 text messages in the hours before and after the assassination on 2 October to his closest adviser Saud al-Qahtani who supervised the 15-man kill-team that was sent to Istanbul, and that Qahtani was in direct communication with the team's leader in Istanbul. The assessment also noted that Mohammed bin Salman had told his agents back in August 2017 that Khashoggi could be lured to a third country, if he could not be persuaded to return to the KSA.[157] However, the message-exchange element of the report was contested by Saudi Arabia based on a confidential Saudi-commissioned investigation conducted by the private security firm Kroll. The investigation, which focused on a forensic examination of a cellphone belonging to Saud al-Qahtani, found that none of the messages exchanged on the day of the murder between Prince Mohammed and Mr. Qahtani concerned the murder.[158]

In September 2019, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman appeared in an interview with the CBS "60 Minutes" program that was aired on 29 September 2019, denying that he had ordered the killing of Jamal Khashoggi or that he had prior knowledge about it but said that he bears all responsibility for the killing of Jamal Khashoggi because the incident took place under his watch. He also said that "once charges are proven against someone, regardless of their rank, it will be taken to court, no exception made."[159][160]

On 25 March 2020, 20 Saudi nationals were reportedly indicted by Turkish prosecutors over the killing of Khashoggi.[161] According to the prosecutor's office in Istanbul, a royal court adviser Saud al-Qahtani, and Saudi's former deputy intelligence chief Ahmed al-Assiri were charged with inciting the murder; both had been investigated by Saudis in 2019 but acquitted or not charged.[162][163] The suspects are believed to have fled Turkey, while Saudi Arabia has denied the Turkish claims for all the accused to be taken back to Turkey in order to answer for their crimes.[164] According to Aljazeera, the charges were filed based on analysis of Khashoggi's accessories, witness testimonies, analysis of the suspects' phone records, including information on their whereabouts within and outside Turkey, as well as the consulate.[165] Arrest warrants have been given out by the Turkish prosecutor for the accused.[166] On 1 July 2020, a Turkish court announced to open the trial in absentia of the 20 indicted Saudi nationals.[167] On 6 July 2020, the United Kingdom imposed sanctions on the 20 Saudi Arabian nationals.[168] On 7 April 2022, a Turkish court ordered the transfer of the trial to Saudi Arabia, despite the fact that many of the suspects had already been acquitted in Saudi Arabia. The decision was criticized by human rights advocates and lawyers involved in the case.[169]

Dismissal of US lawsuit

editOn 18 November 2022, the Biden administration provided a legal opinion that Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman holds immunity over his alleged role in the assassination of Khashoggi. The federal judge deciding a lawsuit had invited the administration's opinion. The Biden administration said that the State Department was offering this opinion "under longstanding and well-established principles of customary international law" unrelated to "the merits of the case". Khashoggi's former fiancee Hatice Cengiz condemned the opinion, stating her feelings that "Jamal died again today" and that the U.S. government was choosing "money" over "justice".[170] Amnesty International called the opinion a "deep betrayal" that "suggests shady deals made throughout."[171] On 6 December, the judge dismissed the lawsuit.[172]

Alleged perpetrators

editAl-Waqt news quoted informed sources as saying that Mohammad bin Salman had assigned Ahmad Asiri, the deputy head of the Saudi intelligence agency Riasat Al-Mukhabarat Al-A'amah[173] and the former spokesman for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, with the mission to execute Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Another military officer with a great deal of experience in dealing with dissidents was the second candidate for the mission.[174] On the same day, Turkish media close to the President published images of what it described as a 15-member "assassination squad" allegedly sent to kill Khashoggi, and of a black van later traveling from the Saudi consulate to the consul's home.[175] On 17 October the Daily Sabah, a news outlet close to the Turkish president, published the names and pictures of the 15-member Saudi team apparently taken at passport control.[176] Additional details about identities were also reported along with their aliases.[177] According to one report, seven of the fifteen men suspected of killing Khashoggi are Mohammed bin Salman's personal bodyguards.[178] The Daily Sabah outlet named and detailed:

- Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb (Arabic: ماهر عبد العزيز مطرب) (born 1971): a former diplomat in London, was photographed with Mohammad bin Salman on trips to Madrid, Paris, Houston, Boston and New York.[179][180][181] (convicted) Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Salah Mohammed al-Tubaigy (Arabic: صلاح محمد الطبيقي) (born 1971): the head of the Saudi Scientific Council of Forensics.[180] (convicted) Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Abdulaziz Mohammed al-Hawsawi (Arabic: عبد العزيز محمد الهوساوي) (born 1987): works as one of Mohammed bin Salman's personal bodyguards.[180]

- Thaer Ghaleb al-Harbi (Arabic: ثائر غالب الحربي) (born 1979): a member of the Saudi Royal Guard.[180] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Mohammed Saad al-Zahrani (Arabic: محمد سعد الزهراني) (born 1988): a member of the Saudi Royal Guard.[180][183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Meshal Saad al-Bostani (Arabic: مشعل سعد البستاني) (born 1987, died 2018): according to Al Jazeera, a lieutenant in the Saudi Air Force.[184] According to Turkish media, he died in a car accident in Riyadh on return to Saudi Arabia.[185][186][187] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Naif Hassan al-Arefe (Arabic: نايف حسن العريفي) (born 1986)[188]

- Mustafa Mohammed al-Madani (Arabic: مصطفى محمد المدني) (born 1961): Khashoggi's body double leaving the Saudi consulate by the back door, dressed in Khashoggi's clothes, a fake beard, and his glasses. The same man was seen at the Blue Mosque, in an attempt to show that Khashoggi had left the consulate unharmed.[112][114][113][183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Mansur Uthman Abahussein (Arabic: منصور عثمان أباحسين) (born 1972)[183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Waleed Abdullah al-Shehri (Arabic: وليد عبد الله الشهري) (born 1980) (convicted),[183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Turki Musharraf al-Shehri (Arabic: تركي مشرف الشهري) (born 1982) (convicted)[183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Fahad Shabib al-Balawi (Arabic: فهد شبيب البلوي) (born 1985) (convicted)[183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Saif Saad al-Qahtani (Arabic: سيف سعد القحطاني) (born 1973) Not charged and released.[183] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[189]

- Khalid Aedh al-Taibi (Arabic: خالد عايض الطيبي) (born 1988)[190] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Badir Lafi al-Otaibi (Arabic: بدر لافي العتيبي) (born 1973)[190] Sanctioned by US Treasury.[182]

- Ahmad Asiri, the deputy head of the Saudi intelligence agency Riasat Al-Mukhabarat Al-A'amah. Sanctioned by US Treasury.[189]

Four of these men had received paramilitary training in the United States in 2017 under a U.S. State Department contract, as was publicly revealed in 2021.[191]

A top Pentagon post nominee of US President Donald Trump, Louis Bremer, was grilled on Capitol Hill by Senator Tim Kaine on 6 August 2020, over his firm Tier 1 Group's alleged involvement in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi. Reportedly, the employees of the private military contracting firm, where Bremer is a member of the board of directors, trained some of the Saudi killers charged in the assassination of Khashoggi. In 2019, David Ignatius – a Washington Post journalist – reported in one of his articles about a similar warning given by the CIA to other government agencies in the US, about Tier 1 Group employees' involvement in the Khashoggi murder case. Bremer denies having any knowledge of the allegations or allegiance of his firm's employees in the Khashoggi assassination.[192][193][194]

Saudi trial and convictions

editThe trial was conducted in secret with diplomats and Khashoggi family members permitted to attend but not speak. The court adhered to the official line that the killing was not premeditated.[195] According to the Saudi prosecutors, ten people were questioned and then released due to lack of evidence against them. A total of 11 people were put on trial by the court.[196] The court conducted ten hearings that were not open to the public. A few foreign diplomats were allowed to attend the hearings after swearing to secrecy. CNN reported that lack of public access made it impossible to understand how the court decided the verdict.[196]

On 23 December 2019, five people were sentenced to death for carrying out Khashoggi's killing:

- Fahad Shabib Albalawi

- Turki Muserref Alshehri

- Waleed Abdullah Alshehri

- Maher Abdulaziz Mutreb, intelligence officer

- Dr Salah Mohammed Tubaigy, a forensic doctor from the Saudi interior ministry[183][196]

Three other defendants, unnamed as of 23 December 2019[update], were sentenced to a combined total of 24 years in prison for "covering up this crime and violating the law".[183][197]

The following defendants were released:

- Saud al-Qahtani, released without charge

- Ahmed al-Assiri, a former deputy intelligence chief, released due to a lack of evidence

- Mohammed al-Otaibi, Saudi Arabia's consul-general in Istanbul, released due to a lack of evidence[189]

The eight Saudis convicted in the verdict can appeal further. Clemency can be offered by Salah Khashoggi, the eldest son of Khashoggi.[189] On 7 September 2020, the Criminal Court in Riyadh issued final convictions for eight people for the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, in which five of them were given 20 years in prison, one received a 10-year sentence, and the other two would serve seven years in prison.[198] The 20-year jail terms were given following Khashoggi's family decision to pardon them, the BBC added.[199] Furthermore, none of the defendants' names were disclosed, according to The Guardian.[200] However, Khashoggi's fiancé went on social media to condemn Saudi Arabia's ruling, describing it as a total mockery of justice. A United Nations expert on human rights who carried out an investigation into the murder also criticized the ruling for lack of transparency or fairness.[201][202]

Response to the Saudi trial

editAccording to Amnesty International's Middle East Research Director Lynn Maalouf, the verdict was a whitewash and the organisation released a statement saying: "The verdict fails to address the Saudi authorities' involvement in this devastating crime or clarify the location of Jamal Khashoggi's remains ... only an international, independent and impartial investigation can serve justice for Jamal Khashoggi."[196]

The United Nations rapporteur on summary executions, Agnès Callamard, described the sentence as a "mockery" of justice, since, according to her, it was an "extrajudicial execution for which the state of Saudi Arabia is responsible" and its masterminds walk free.[203]

Although Khashoggi's sons reportedly accepted the 2019 verdict,[196] they pardoned the five officials on 22 May 2020, which means the officials would not be executed but their families are to pay blood money to Khashoggi's family.[20]

Reporters sans frontières lawsuit in Germany

editOn 1 March 2021 Reporters sans frontières (RSF) filed a criminal case in the Federal Court of Justice in Karlsruhe against Crown Prince bin Salman for "crimes against humanity" in the murder of Khashoggi, additionally for the arbitrary detention of 34 journalists. RSF cited the Code of Crimes Against International Law (VStGB), under which the specified journalists are victims of multiple counts of crimes against humanity, "including willful killing, torture, sexual violence and coercion, enforced disappearance, unlawful deprivation of physical liberty, and persecution."[204][205][206]

Economic and political boycotts

editUber's CEO Dara Khosrowshahi made calls to boycott Saudi Arabia over the death of Khashoggi.[207]

In October 2018, the UK and the US joined their major European partners in pulling out of a Saudi Arabia's economic forum nicknamed Davos in the desert, in response to the murder of Khashoggi.[208]

WWE was criticized over their Crown Jewel event in Saudi Arabia and failure to boycott the country over the death of Khashoggi.[209] WWE's Chief Brand Officer, Stephanie McMahon said that "at the end of the day, it is a business decision and, like a lot of other American companies, we decided that we're going to move forward with the event and deliver Crown Jewel for all of our fans in Saudi Arabia and around the world".[210]

Following Khashoggi's assassination, the Turkish president, Erdogan, did not travel to Saudi Arabia again until April 2022, when he met with Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman.[211]

Aftermath

editOn 22 October 2018, Khashoggi's son and brother were summoned to a photo op with King Salman and the heir to the throne, at the Palace of Yamamah, in Riyadh. Salah bin Jamal Khashoggi and his uncle Sahel were received by the royals. Pictures of the event went viral, amid reports that Salah, who lives in Jeddah, has been banned from leaving the country since 2017. A family friend, Yehia Assiri, described the event as "a serious assault on the family".[212][213] Nick Paton Walsh, a senior international correspondent, described it as "a remarkable display of the sustained and catastrophic disconnect between Riyadh and the outside world. As if PR is something you shoot yourself in the foot with."[214] On 24 October 2018, Salah Khashoggi, who holds dual Saudi-US citizenship, and his family left Saudi Arabia for the US.[215]

Other alleged abduction attempts

editFollowing Jamal Khashoggi's killing and mutilation, several other exiled Saudi activists reported that the Saudi regime attempted to lure them into their embassies.[216] Middle East Eye published claims from an unnamed source with knowledge of Saudi intelligence agencies that the murder is part of a larger operation of silently murdering critics of Saudi government by a death squad named "Tiger Squad", composed of the most trusted and skilled intelligence agents. According to the source, the Tiger Squad assassinates dissidents using varying methods such as planned car accidents, house fires, or poisoning clinics by injecting toxic substances into opponents when they attend regular health checkups. The alleged group members are recruited from different branches of the Saudi forces, directing several areas of expertise. According to Middle East Eye, five members were part of the 15-member death squad who were sent to murder Khashoggi.[80]

Exiled Saudi activist Omar Abdulaziz said he was approached earlier in 2018 by Saudi officials who urged him to visit the Saudi embassy in Ottawa, Canada with them to collect a new passport. The Saudi activist stated that the officials from the Saudi regime "were saying 'it will only take one hour; just come with us to the embassy.'" After Omar Abdulaziz refused, Saudi authorities arrested two of his brothers and several of his friends in Saudi Arabia.[citation needed] Abdulaziz secretly recorded his conversations with those officials, which were several hours long, and provided them to The Washington Post.[217] The source interviewed by Middle East Eye also said the team planned to kill Omar Abdelaziz and claimed prince Mansour bin Muqrin was assassinated by the squad by shooting down his personal aircraft as he was fleeing the country on 5 November 2017 and made to appear as an accidental crash.[80]

Opposition Saudi scholar Abdullah Alaoudh (son of Salman al-Ouda) said he was subjected to a similar plot when he sent in a passport renewal application to the Saudi Embassy in Washington. Alaoudh said, "They offered me a 'temporary pass' that Prominent Saudi women's rights activist Manal al-Sharif also separately reported a similar event during her exile in Australia, having said: "If it weren't for the kindness of God I would have been [another] victim."[216] The Tiger Squad also reportedly killed Suleiman Abdul Rahman al-Thuniyan, a Saudi court judge who was murdered by an injection of a deadly virus into his body when he had visited a hospital for a regular health checkup. "One of the techniques the Tiger Squad uses to silence dissidents or opponents of the government is to 'kill them with HIV, or other sorts of deadly viruses'".[80]

In August 2020, a lawsuit filed by exiled former minister of state, Saad Aljabri, alleged that members of the Tiger Squad were sent to Canada to assassinate him two weeks after Khashoggi was killed, but that they were denied entry by Canadian border security.[218][219] Additionally, Aljabri's son, Khalid, has claimed that his brother-in-law was rendered from Dubai to Saudi Arabia in September 2017, where he was coerced into trying to persuade his wife to attend the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul. Khalid suspects she would have been abducted had she gone there.[220]

In July 2022, the United Arab Emirates' authorities arrested an American lawyer, Asim Ghafoor, while he was transiting from the Dubai International Airport. Ghafoor was informed that he was tried, convicted, and sentenced in absentia. The UAE claimed of convicting him of tax evasion and money laundering, and in coordination of the United States.[221][222] However, Ghafoor faced no criminal charges in the States.[223] The U.S. said it did not request the Emirates to arrest Ghafoor.[224] His attorney, Faisal Gill, said Ghafoor never heard anything about the conviction before the arrest and didn't see any documents for the government's charges.[223] It was being asserted that Ghafoor was arrested for his close ties with Jamal Khashoggi. They both together founded the organization Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN), which is strong critic of the human rights abuses in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and the arms sales by the US to these countries. Ghafoor is still a board member at DAWN. Besides, he had also served as Khashoggi's lawyer. Rights groups said Ghafoor was another victim of UAE's practice of convicting activists, lawyers and academics on broad charges.[225][222] On 13 August 2022, Ghafoor was released by the Emirati authorities after paying a fine of $1.4 million.[226] The UAE court also confiscated nearly $4.9 million from Ghafoor.[227]

Reactions

editFor 18 days, Saudi Arabian officials denied Khashoggi had died in the consulate, before indicating a team of Saudi agents had overstepped their orders to capture him when a struggle ensued leading to his death.[228] Turkey's president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, said he believes the killing was premeditated and approved by the Saudi government, and sought extradition of the suspects.[229] The United States' president, Donald Trump, expressed support for the Saudi government, reserving judgment about culpability.[99] This created a bipartisan uproar in Congress, and 22 senators petitioned Trump to consider investigating whether Saudi Arabia should be sanctioned for human rights violations.[230] Several countries called for a transparent investigation and condemned the killing. Allied Arab countries characterized the aftermath as a media campaign against Saudi Arabia.[231]

Germany, Norway and Denmark[232] stopped the sale of arms to Saudi Arabia over the incident. Canada considered freezing its $13 billion General Dynamics Land Systems – Canada arms deal,[233] but so far has chosen to proceed with the deal.[234][235]

According to a U.S. senator, the Trump administration granted authorizations to U.S. companies to share sensitive nuclear power information with Saudi Arabia shortly after the assassination of Jamal Khashoggi.[236] In July 2019, Trump vetoed three bipartisan congressional resolutions that would have halted arms sales.[237] However, in February 2021, the Biden administration declassified a brief report that blamed Mohammed bin Salman as having approved the assassination, thereby implying that the administration planned to adjust U.S.–Saudi relations.[238]

On 11 December 2018, Khashoggi was named as a person of the year by Time magazine for his work in journalism, along with other journalists who faced political persecution for their work. Time referred to Khashoggi, and the others, as a "Guardian of the Truth".[239][240][241]

In mid-August 2020, the Open Society Justice Initiative, part of Open Society Foundations, filed a lawsuit in the district court of New York demanding the release of the government's report on Jamal Khashoggi's murder, under the Freedom of Information Act. In July, they filed for a similar request, but received no response from the authority on the legal deadline.[242]

A Showtime original documentary about the murder of Khashoggi, Kingdom of Silence, was released on 2 October 2020, the second anniversary of his death. It was directed by Richard Rowley.[243][244][245]

In 2020, a documentary on the assassination of Khashoggi and the role played by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was made by an Oscar-winning film director and producer, Bryan Fogel. However, it took eight months for Fogel to find a streaming service for The Dissident, which was released by an independent company.[246][247]

See also

edit- Saudi Arabia–Turkey relations

- The Dissident – a 2020 American documentary film about the assassination of Khashoggi, directed by Bryan Fogel

- Freedom of the press

- Pegasus (spyware)

- Human rights in Saudi Arabia

- Israa al-Ghomgham – Saudi human rights activist who documented the 2017–18 Qatif unrest and faces execution by beheading

- Sheikh Baqir al-Nimr – dissident cleric executed for criticism of the Saudi regime

- Ali Mohammed Baqir al-Nimr, (Sheikh Baqir al-Nimr's nephew), participated in the protests during the Arab Spring, arrested at the age of 17 and sentenced to death, to be carried out by beheading and crucifixion

- Salman al-Ouda – cleric in the city of Riyadh, urged the Saudi monarchy to launch democratic reforms, sentenced to death in September 2018[248]

- Raif Badawi – imprisoned Saudi dissident, writer and activist

- Hamza Kashgari – pro-democracy activist and columnist imprisoned for blasphemy

- Dina Ali Lasloom – imprisoned Saudi asylum seeker

- Samar Badawi – imprisoned Saudi activist

- Fahad al-Butairi – abducted in Jordan and taken to be imprisoned in Saudi Arabia

- Manal al-Sharif – Saudi human rights activist

- Loujain al-Hathloul – imprisoned Saudi activist

- Mishaal bint Fahd bin Mohammed Al Saud – Saudi princess executed for alleged adultery

- Sara bint Talal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud – exiled Saudi princess and regime critic

- 2016 Saudi Arabia mass execution

- 2017 Saad Hariri affair

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Harris, Shane; Miller, Greg; Dawsey, Josh (16 November 2018). "CIA concludes Saudi crown prince ordered Jamal Khashoggi's assassination". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ a b ""Where Is Jamal?": Fiancee Of Missing Saudi Journalist Demands To Know and get MBS who said in a statement "THUG LIFE" as reporter Jonathan Mejia asks". NDTV. The Washington Post. 9 October 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ a b Fahim, Kareem (6 October 2018). "Saudi forensic expert is among 15 named by Turkey in disappearance of journalist Jamal Khashoggi". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E.; Schmitt, Eric; Kirkpatrick, David D. (12 November 2018). "'Tell Your Boss': Recording Is Seen to Link Saudi Crown Prince More Strongly to Khashoggi Killing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ a b c "Jamal Khashoggi: An unauthorized Turkey source says journalist was murdered in Saudi consulate". BBC News. 7 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Sakelaris, Nicholas (26 September 2019). "Saudi Prince bin Salman accepts responsibility but not blame for Khashoggi death". UPI. Archived from the original on 10 April 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick, David D.; Cumming-Bruce, Nick (19 June 2019). "Saudis Called Khashoggi 'Sacrificial Animal' as They Waited to Kill Him". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Uras, Umut (31 October 2018). "Turkey: Khashoggi strangled immediately after entering consulate". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ Corbin, Jane (29 September 2019). "The secret tapes of Jamal Khashoggi's murder". BBC News. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Audio transcripts of Jamal Khashoggi's murder revealed". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben (3 January 2019). "Saudi Arabia Seeks Death Penalty for 5 Suspects in Khashoggi Killing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b Smith, Saphora (25 October 2018). "Saudis change Khashoggi story again, admit killing was 'premeditated'". NBC News. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Saudis now admit journalist was murdered". BBC News. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ a b El Sirgany, Sarah; Altaher, Nada; Britton, Bianca. "Saudis seek death penalty, details Khashoggi's death". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ a b Chappell, Bill (15 November 2018). "Khashoggi Case Update: Saudi Prosecutor Says 5 Suspects Should Be Executed". NPR. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Hjelmgaard, Kim (15 November 2018). "US sanctions 17 Saudi nationals over Jamal Khashoggi's killing". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Edelman, Adam; Bruton, Brinley (21 November 2018). "In unusual statement disputing the CIA and filled with exclamation points, Trump backs Saudi ruler after Khashoggi killing". NBC News. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rashad, Marwa; Hosenball, Mark (23 December 2019). "Saudi Arabia sentences five to death over Khashoggi murder, U.N. official decries 'mockery'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Abdulaziz, Donna. "Saudi Arabia Begins Trial in Khashoggi Murder". WSJ. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ a b Tawfeeq, Mohammed; Karadsheh, Jomana; Qiblawi, Tamara; Robertson, Nic (22 May 2020). "Khashoggi's children 'pardon' their father's killers, sparing them the death penalty". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Speakers". International Public Relations Association – Gulf Chapter (IPRA-GC). 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Hendley, Paul (17 May 2010). "Saudi newspaper head resigns after run-in with conservatives". Al Hdhod. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ a b Shaban, Mohammed (23 October 2018). "Khashoggi was victim of Saudi internet trolls, friend tells Euronews". Euronews. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Turkey says journalist Khashoggi 'killed at Saudi consulate'". France 24. 7 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b "How the man behind Khashoggi murder ran the killing via Skype". Reuters. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Benner, Katie; Mazzetti, Mark; Hubbard, Ben; Isaac, Mike (20 October 2018). "Saudis' Image Makers: A Troll Army and a Twitter Insider". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Groll, Elias (19 October 2018). "The Kingdom's Hackers and Bots Saudi Arabia is using cutting-edge technology to track dissidents and stifle dissent". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Warrick, Joby; Morris, Loveday; Mekhennet, Souad (20 October 2018). "In death, Saudi writer's mild calls for reform grew into a defiant shout". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Khashoggi, Jamal (17 October 2018). "What the Arab world needs most is free expression". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Stancati, Margherita; Said, Summer (2 November 2018). "Behind Saudi Prince's Crackdown Was Confidant Tied to Khashoggi Killing". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019 – via wsj.com.

- ^ a b Marczak, Bill; Scott-Railton, John; Senft, Adam; Razzak, Bahr Abdul; Deibert, Ron (1 October 2018). "The Kingdom Came to Canada How Saudi-Linked Digital Espionage Reached Canadian Soil". Citizen Lab. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "Amnesty International Among Targets of NSO-powered Campaign". amnesty.org. August 2018. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Morris, Loveday; Zakaria, Zakaria (17 October 2018). "Secret recordings give insight into Saudi attempt to silence critics". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Asher-Schapiro, Avi (31 October 2018). "How the Saudis may have spied on Jamal Khashoggi". Committee to Protect Journalists. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ a b Trew, Bel (20 October 2018). "Bee stung: Was Jamal Khashoggi the first casualty in a Saudi cyberwar?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ a b Cengiz, Hatice (9 October 2018). "Please, President Trump, shed light on my fiance's disappearance". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Statement on Jamal Khashoggi". Wilson Center. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ Alexander, Nazaryan (15 October 2018). "Think tanks reconsider Saudi support amid Khashoggi controversy". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ Brewster, Thomas. "Exclusive: Saudi Dissidents Hit With Stealth iPhone Spyware Before Khashoggi's Murder". Forbes. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Khashoggi messages reveal sharp criticism of MBS". Youtube. CNN. 2 December 2018. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ dos Santos, Nina; Kaplan, Michael (3 December 2018). "Jamal Khashoggi's private WhatsApp messages may offer new clues to killing". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (2 December 2018). "Israeli Software Helped Saudis Spy on Khashoggi, Lawsuit Says". NYT. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Harris, Shane (10 October 2018). "Crown prince sought to lure Khashoggi back to Saudi Arabia and detain him, U.S. intercepts show". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Morris, Loveday; Mekhennet, Souad; Fahim, Kareem (10 October 2018). "Saudis are said to have lain in wait for Jamal Khashoggi". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben; Kirkpatrick, David D. (14 October 2018). "For Khashoggi, a Tangled Mix of Royal Service and Islamist Sympathies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "Friends of Saudi dissident say he failed to return after visit to Istanbul consulate". CNBC. Reuters. 2 October 2018. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

Khashoggi was in the United States on an O-visa

- ^ a b Timmons, Heather (19 October 2018). "What does the US owe Jamal Khashoggi?". Quartz. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

Khashoggi was living in the United States on an 'O' visa ... Three of Khashoggi's children are US citizens.

- ^ Schindler, John R. (10 October 2018). "NSA: White House Knew Jamal Khashoggi Was In Danger". Observer. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Herrmann, Frank (21 October 2018). "Außenminister Saudi-Arabiens sieht Tötung Khashoggis als Fehler". Der Standard (in German). Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "US intelligence being sued for failing to warn Khashoggi of threat". The Middle East Monitor. 21 November 2018. Archived from the original on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ "Knight Institute Sues to Learn Whether U.S. Intelligence Agencies Complied With "Duty to Warn" Reporter Jamal Khashoggi of Threats to His Life". Knight First Amendment Institute. 20 November 2018. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b Kirchgaessner, Stephanie (19 January 2021). "Biden administration 'to declassify report' into Khashoggi murder". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Biden intel chief nominee vows to release Khashoggi murder report". Al Jazeera. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Assessing the Saudi Government's Role in the Killing of Jamal Khashoggi" (PDF). ODNI. 11 February 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Assessing the Saudi Government's Role in the Killing of Jamal Khashoggi (v2)" (PDF). Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 26 February 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Marquardt, Alex (March 2021). "Three names mysteriously removed from Khashoggi intelligence report after initial publication". CNN. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Jamal Khashoggi: US says Saudi prince approved Khashoggi killing". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Kirchgaessner, Stephanie (4 March 2021). "US decision not to punish crown prince puts us in grave danger, Saudi exiles say". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Lederman, Josh (22 October 2018). "Khashoggi met with crown prince's brother amid efforts to return him to Saudi Arabia". NBC News. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Did Embassy in DC send Khashoggi to Istanbul?". Euronews. Reuters and NBC. 9 October 2018. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Boris (21 October 2018). "The murder of Jamal Khashoggi was a barbaric act. We mustn't let Saudi Arabia off the hook". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

First there was the transparent ruse by which the Saudi-born Washington Post columnist was tricked into endangering himself by leaving the United States.

- ^ Chulov, Martin; Wintour, Patrick (9 October 2018). "Jamal Khashoggi: Turkey hunts black van it believes carried body". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Pannell, Ian (30 October 2018). "Though Khashoggi didn't suspect he may be in danger, he was still apprehensive". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b c Gall, Carlotta (3 October 2018). "What Happened to Jamal Khashoggi? Conflicting Reports Deepen a Mystery". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "Key moments surrounding the killing of Jamal Khashoggi". AP News. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Erdogan on Khashoggi vanishing: Upsetting this happens in Turkey". Al Jazeera. 8 October 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ "Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi disappears after entering Saudi Arabia's consulate in Istanbul". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Reuters. 7 October 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Meixler, Eli; Perrigo, Billy (9 October 2018). "A Columnist Walked Into Saudi Arabia's Consulate. Then He Went Missing". Time. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Seine Verlobte im Interview: Aus diesem Grund ging Khashoggi beim zweiten Mal unbesorgt in das Konsulat". Die Welt (in German). 26 October 2018. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "News snippet". Saudi Press Agency. 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 6 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "Jamal Khashoggi: Washington Post blanks out missing Saudi writer's column". BBC. 5 October 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Ingber, Sasha (4 October 2018). "Saudi Critic Vanishes After Visiting Consulate, Prompting Fear And Confusion". NPR. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Chulov, Martin; McKernan, Bethan (10 October 2018). "Jamal Khashoggi: details of alleged Saudi hit squad emerge". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ a b Chulov, Martin (9 October 2018). "Khashoggi case: CCTV disappears from Saudi consulate in Turkey". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b Robinson, Joan (13 October 2018). "Jamal Khashoggi Case: A contemporary thriller". National Herald. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Coskun, Orhan (6 October 2018). "Exclusive: Turkish police believe Saudi journalist Khashoggi was killed in consulate – sources". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Turkish police suspect Saudi journalist Khashoggi was killed at consulate". Middle East Eye. 6 October 2018. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (6 October 2018). "Turkey concludes Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi killed by 'murder' team, sources say". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b Chulov, Martin (6 October 2018). "Saudi journalist 'killed inside consulate' – Turkish sources". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d Abu Sneineh, Mustafa (22 October 2018). "REVEALED: The Saudi death squad MBS uses to silence dissent". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Harris, Shane; Mekhennet, Souad; Hudson, John; Gearan, Anne (11 October 2018). "Turks tell U.S. officials they have audio and video recordings that support conclusion Khashoggi was killed". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ "We've asked for Khashoggi tape evidence – Trump". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ^ Harris, Shane (19 October 2018). "Saudi claims that Khashoggi died in a 'brawl' draw immediate skepticism". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ a b Ward, Clarissa; Lister, Tim (15 October 2018). "Saudis preparing to admit Jamal Khashoggi died during interrogation, sources say". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Marquardt, Alex (25 February 2021). "'Top Secret' Saudi documents show Khashoggi assassins used company seized by Saudi crown prince". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b Hearst, David (10 December 2018). "Jamal Khashoggi's killing took seven minutes, Turkish source tells MEE". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Vankin, Jonathan (16 October 2018). "Jamal Khashoggi Dismembered Alive, Saudi Killer Listened To Music During Murder". Inquisitr. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.