The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (Spanish: Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis (Russian: Карибский кризис, romanized: Karibskiy krizis), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey were matched by Soviet deployments of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis lasted from 16 to 28 October 1962. The confrontation is widely considered the closest the Cold War came to escalating into full-scale nuclear war.[1]

| Cuban Missile Crisis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution | |||||||

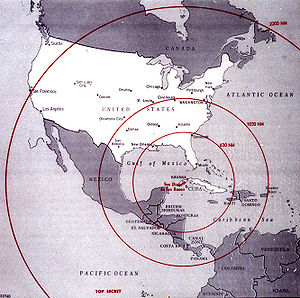

US intelligence map showing their estimates of the range of the missiles stationed in Cuba | |||||||

| |||||||

| Parties involved in the crisis | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| 100,000–180,000 (estimated) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None |

| ||||||

In 1961 the US government put Jupiter nuclear missiles in Italy and Turkey. It had trained a paramilitary force of expatriate Cubans, which the CIA led in an attempt to invade Cuba and overthrow its government. Starting in November of that year, the US government engaged in a violent campaign of terrorism and sabotage in Cuba, referred to as the Cuban Project, which continued throughout the first half of the 1960s. The Soviet administration was concerned about a Cuban drift towards China, with which the Soviets had an increasingly fractious relationship. In response to these factors the Soviet and Cuban governments agreed, at a meeting between leaders Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro in July 1962, to place nuclear missiles on Cuba to deter a future US invasion. Construction of launch facilities started shortly thereafter.

A U-2 spy plane captured photographic evidence of medium- and long-range launch facilities in October. US President John F. Kennedy convened a meeting of the National Security Council and other key advisers, forming the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM). Kennedy was advised to carry out an air strike on Cuban soil in order to compromise Soviet missile supplies, followed by an invasion of the Cuban mainland. He chose a less aggressive course in order to avoid a declaration of war. On 22 October Kennedy ordered a naval blockade to prevent further missiles from reaching Cuba.[2] He referred to the blockade as a "quarantine", not as a blockade, so the US could avoid the formal implications of a state of war.[3]

An agreement was eventually reached between Kennedy and Khrushchev. Publicly, the Soviets would dismantle their offensive weapons in Cuba, subject to United Nations verification, in exchange for a US public declaration and agreement not to invade Cuba again. Secretly, the United States agreed to dismantle all of the offensive weapons it had deployed to Turkey. There has been debate on whether Italy was also included in the agreement. While the Soviets dismantled their missiles, some Soviet bombers remained in Cuba, and the United States kept the naval quarantine in place until 20 November 1962.[3][4] The blockade was formally ended on 20 November after all offensive missiles and bombers had been withdrawn from Cuba. The evident necessity of a quick and direct communication line between the two powers resulted in the Moscow–Washington hotline. A series of agreements later reduced US–Soviet tensions for several years.

The compromise embarrassed Khrushchev and the Soviet Union because the withdrawal of US missiles from Italy and Turkey was a secret deal between Kennedy and Khrushchev, and the Soviets were seen as retreating from a situation that they had started. Khrushchev's fall from power two years later was in part because of the Soviet Politburo's embarrassment at both Khrushchev's eventual concessions to the US and his ineptitude in precipitating the crisis. According to the Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, the top Soviet leadership took the Cuban outcome as "a blow to its prestige bordering on humiliation".[5][6]

Background

editCuba–Soviet relations

editIn late 1961, Fidel Castro asked for more SA-2 anti-aircraft missiles from the Soviet Union. The request was not acted upon by the Soviet leadership. In the interval, Castro began criticizing the Soviets for lack of "revolutionary boldness", and began talking to China about agreements for economic assistance. In March 1962, Castro ordered the ousting of Anibal Escalante and his pro-Moscow comrades from Cuba's Integrated Revolutionary Organizations. This affair alarmed the Soviet leadership as well as raised fears of a possible US invasion. As a result, the Soviet Union sent more SA-2 anti-aircraft missiles in April as well as a regiment of regular Soviet troops.[7]

Historian Timothy Naftali has contended that Escalante's dismissal was a motivating factor behind the Soviet decision to place nuclear missiles in Cuba in 1962. According to Naftali, Soviet foreign policy planners were concerned Castro's break with Escalante foreshadowed a Cuban drift toward China and sought to solidify the Soviet-Cuban relationship through the missile basing program.[8]

Cuba–US relations

editThe Cuban government regarded US imperialism as the primary explanation for the island's structural weaknesses.[9] The US government provided weapons, money, and its authority to the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista that ruled Cuba until 1958. The majority of the Cuban population had tired of the severe socioeconomic problems associated with the US domination of the country. The Cuban government was thus aware of the necessity of ending the turmoil and incongruities of US-dominated prerevolution Cuban society. It determined that the US government's demands, made as part of the hostile US reaction to Cuban government policy, were unacceptable.[9][10]

With the end of World War II and the start of the Cold War, the United States government sought to promote private enterprise as an instrument for advancing US strategic interests in the developing world.[11] It had grown concerned about the expansion of communism.

In December 1959, under the Eisenhower administration and less than twelve months after the Cuban Revolution, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) developed a plan for paramilitary action against Cuba. The CIA recruited operatives on the island to carry out terrorism and sabotage, kill civilians, and cause economic damage.[16] At the initiative of the CIA Deputy Director for Plans, Richard Bissell, and approved by the new President John F. Kennedy, the US launched the attempted Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961. It used CIA-trained forces of Cuban expatriates. The complete failure of the invasion, and the exposure of the US government role before the operation began, was a source of diplomatic embarrassment for the Kennedy administration. Afterward, former President Eisenhower told Kennedy that "the failure of the Bay of Pigs will embolden the Soviets to do something that they would otherwise not do."[17]: 10

Following the failed invasion, the US massively escalated its sponsorship of terrorism against Cuba. Starting in late 1961, using the military and the CIA, the US government engaged in an extensive campaign of state-sponsored terrorism against civilian and military targets on the island. The terrorist attacks killed significant numbers of civilians. The US armed, trained, funded and directed the terrorists, most of whom were Cuban expatriates. Terrorist attacks were planned at the direction and with the participation of US government employees and launched from US territory.[23] In January 1962, US Air Force General Edward Lansdale described the plans to overthrow the Cuban government in a top-secret report, addressed to Kennedy and officials involved with Operation Mongoose.[24][15] CIA agents or "pathfinders" from the Special Activities Division were to be infiltrated into Cuba to carry out sabotage and organization, including radio broadcasts.[25] In February 1962, the US launched an embargo against Cuba,[26] and Lansdale presented a 26-page, top-secret timetable for implementation of the overthrow of the Cuban government, mandating guerrilla operations to begin in August and September. "Open revolt and overthrow of the Communist regime" was hoped by the planners to occur in the first two weeks of October.[15]

The terrorism campaign and the threat of invasion were crucial factors in the Soviet decision to position the missiles on Cuba, and in the Cuban government's decision to accept.[31] The US government was aware at the time, as reported to the president in a National Intelligence Estimate, that the invasion threat was a key reason for Cuban acceptance of the missiles.[32][33]

US–Soviet relations

editWhen Kennedy ran for president in 1960, one of his key election issues was an alleged "missile gap" with the Soviets. In fact, the US at that time led the Soviets by a wide margin, which would only increase over time. In 1961, the Soviets had only four R-7 Semyorka intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). By October 1962, some intelligence estimates indicated a figure of 75.[34]

The US, on the other hand, had 170 ICBMs and was quickly building more. It also had eight George Washington- and Ethan Allen-class ballistic missile submarines, with the capability to launch 16 Polaris missiles, each with a range of 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km). The Soviet First Secretary, Nikita Khrushchev, increased the perception of a missile gap when he loudly boasted to the world that the Soviets were building missiles "like sausages" but Soviet missiles' numbers and capabilities were nowhere close to his assertions. The Soviet Union had medium-range ballistic missiles in quantity, about 700 of them, but they were unreliable and inaccurate. The US had a considerable advantage in its total number of nuclear warheads (27,000 against 3,600) and in the technology required for their accurate delivery. The US also led in missile defensive capabilities, naval and air power; however, the Soviets held a two-to-one advantage in conventional ground forces, more pronounced in field guns and tanks, particularly in the European theatre.[34]

Khrushchev also had an impression of Kennedy as weak, which to him was confirmed by the President's response during the Berlin Crisis of 1961, particularly to the building of the Berlin Wall by East Germany to prevent its citizens from emigrating to the West.[35] The half-hearted nature of the Bay of Pigs invasion reinforced Khrushchev's and his advisers' impression that Kennedy was indecisive and, as one Soviet aide wrote, "too young, intellectual, not prepared well for decision making in crisis situations... too intelligent and too weak".[17] Speaking to Soviet officials in the aftermath of the crisis, Khrushchev asserted, "I know for certain that Kennedy doesn't have a strong background, nor, generally speaking, does he have the courage to stand up to a serious challenge." He also told his son Sergei that on Cuba, Kennedy "would make a fuss, make more of a fuss, and then agree".[36]

Prelude

editConception

editIn May 1962, Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev was persuaded by the idea of countering the US's growing lead in developing and deploying strategic missiles by placing Soviet intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Cuba, despite the misgivings of the Soviet Ambassador in Havana, Alexandr Ivanovich Alexeyev, who argued that Castro would not accept the deployment of the missiles.[37] Khrushchev faced a strategic situation in which the US was perceived to have a "splendid first strike" capability that put the Soviet Union at a huge disadvantage. In 1962, the Soviets had only 20 ICBMs capable of delivering nuclear warheads to the US from inside the Soviet Union.[38] The poor accuracy and reliability of the missiles raised serious doubts about their effectiveness. A newer, more reliable generation of ICBMs would become operational only after 1965.[38]

Therefore, Soviet nuclear capability in 1962 placed less emphasis on ICBMs than on medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs and IRBMs). The missiles could hit American allies and most of Alaska from Soviet territory but not the contiguous United States. Graham Allison, the director of Harvard University's Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, points out, "The Soviet Union could not right the nuclear imbalance by deploying new ICBMs on its own soil. In order to meet the threat it faced in 1962, 1963, and 1964, it had very few options. Moving existing nuclear weapons to locations from which they could reach American targets was one."[39]

A second reason that Soviet missiles were deployed to Cuba was that Khrushchev wanted to bring West Berlin, controlled by the American, British and French within Communist East Germany, into the Soviet orbit. The East Germans and Soviets considered western control over a portion of Berlin a grave threat to East Germany. Khrushchev made West Berlin the central battlefield of the Cold War. Khrushchev believed that if the US did nothing over the missile deployments in Cuba, he could muscle the West out of Berlin using said missiles as a deterrent to western countermeasures in Berlin. If the US tried to bargain with the Soviets after it became aware of the missiles, Khrushchev could demand trading the missiles for West Berlin. Since Berlin was strategically more important than Cuba, the trade would be a win for Khrushchev, as Kennedy recognized: "The advantage is, from Khrushchev's point of view, he takes a great chance but there are quite some rewards to it."[40]

Thirdly, from the perspective of the Soviet Union and of Cuba, it seemed that the United States wanted to invade or increase its presence in Cuba. In view of actions including the attempt to expel Cuba from the Organization of American States,[41] the ongoing campaign of violent terrorist attacks on civilians the US was carrying out against the island,[23] economic sanctions against the country, and the earlier attempt to invade it, Cuban officials understood that America was trying to overrun the country. As a result, to try to prevent this, the USSR would place missiles in Cuba and neutralise the threat. This would ultimately serve to secure Cuba against attack and keep the country in the Socialist Bloc.[29]

Another major reason why Khrushchev planned to place missiles on Cuba undetected was to "level the playing field" with the evident American nuclear threat. America had the upper hand as they could launch from Turkey and destroy the USSR before they would have a chance to react. After the emplacement of nuclear missiles in Cuba, Khrushchev had finally established mutual assured destruction, meaning that if the United States decided to launch a nuclear strike against the Soviet Union, the latter would react by launching a retaliatory nuclear strike against the US.[42]

Finally, placing nuclear missiles on Cuba was a way for the USSR to show their support for Cuba and support the Cuban people who viewed the United States as a threatening force,[41] as the USSR had become Cuba's ally after the Cuban Revolution of 1959. According to Khrushchev, the Soviet Union's motives were "aimed at allowing Cuba to live peacefully and develop as its people desire".[43]

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., a historian and adviser to Kennedy, told National Public Radio in an interview on 16 October 2002, that Castro did not want the missiles, but Khrushchev pressured Castro to accept them. Castro was not completely happy with the idea, but the Cuban National Directorate of the Revolution accepted them, both to protect Cuba against US attack and to aid the Soviet Union.[44]: 272

Soviet military deployments

editIn early 1962, a group of Soviet military and missile construction specialists accompanied an agricultural delegation to Havana. They obtained a meeting with Cuban prime minister Fidel Castro. According to one report, Cuban leadership had a strong expectation that the US would invade Cuba again and enthusiastically approved the idea of installing nuclear missiles in Cuba. According to another source, Castro objected to the missiles' deployment as making him look like a Soviet puppet, but he was persuaded that missiles in Cuba would be an irritant to the US and help the interests of the entire socialist camp.[45] The deployment would include short-range tactical weapons (with a range of 40 km, usable only against naval vessels) that would provide a "nuclear umbrella" for attacks upon the island.

By May, Khrushchev and Castro agreed to place strategic nuclear missiles secretly in Cuba. Like Castro, Khrushchev felt that a US invasion of Cuba was imminent and that to lose Cuba would do great harm to the communists, especially in Latin America. He said he wanted to confront the Americans "with more than words.... the logical answer was missiles".[46] The Soviets maintained their tight secrecy, writing their plans longhand, which were approved by Marshal of the Soviet Union Rodion Malinovsky on 4 July and Khrushchev on 7 July.

From the very beginning, the Soviets' operation entailed elaborate denial and deception, known as "maskirovka". All the planning and preparation for transporting and deploying the missiles were carried out in the utmost secrecy, with only a very few told the exact nature of the mission. Even the troops detailed for the mission were given misdirection by being told that they were headed for a cold region and being outfitted with ski boots, fleece-lined parkas, and other winter equipment. The Soviet code-name was Operation Anadyr. The Anadyr River flows into the Bering Sea, and Anadyr is also the capital of Chukotsky District and a bomber base in the far eastern region. All the measures were meant to conceal the program from both internal and external audiences.[47]

Specialists in missile construction, under the guise of machine operators and agricultural specialists, arrived in July.[47] A total of 43,000 foreign troops would ultimately be brought in.[48][49] Chief Marshal of Artillery Sergei Biryuzov, Head of the Soviet Rocket Forces, led a survey team that visited Cuba. He told Khrushchev that the missiles would be concealed and camouflaged by palm trees.[34] The Soviet troops would arrive in Cuba heavily underprepared. They did not know that the tropical climate would render ineffective many of their weapons and much of their equipment. In the first few days of setting up the missiles, troops complained of fuse failures, excessive corrosion, overconsumption of oil, and generator blackouts.[50]

As early as August 1962, the US suspected the Soviets of building missile facilities in Cuba. During that month, its intelligence services gathered information about sightings by ground observers of Soviet-built MiG-21 fighters and Il-28 light bombers. U-2 spy planes found S-75 Dvina (NATO designation SA-2) surface-to-air missile sites at eight different locations. CIA director John A. McCone was suspicious. Sending antiaircraft missiles into Cuba, he reasoned, "made sense only if Moscow intended to use them to shield a base for ballistic missiles aimed at the United States".[51] On 10 August, he wrote a memo to Kennedy in which he guessed that the Soviets were preparing to introduce ballistic missiles into Cuba.[34] Che Guevara himself traveled to the Soviet Union on 30 August 1962, to sign off on the final agreement regarding the deployment of missiles in Cuba.[52] The visit was heavily monitored by the CIA as Guevara had gained more scrutiny by American intelligence. While in the Soviet Union Guevara argued with Khrushchev that the missile deal should be made public but Khrushchev insisted on total secrecy, and swore the Soviet Union's support if the Americans discovered the missiles. By the time Guevara arrived in Cuba the United States had already discovered the Soviet troops in Cuba via U-2 spy planes.[53]

With important Congressional elections scheduled for November, the crisis became enmeshed in American politics. On 31 August, Senator Kenneth Keating (R-New York) warned on the Senate floor that the Soviet Union was "in all probability" constructing a missile base in Cuba. He charged the Kennedy administration with covering up a major threat to the US, thereby starting the crisis.[54] He may have received this initial "remarkably accurate" information from his friend, former congresswoman and ambassador Clare Boothe Luce, who in turn received it from Cuban exiles.[55] A later confirming source for Keating's information possibly was the West German ambassador to Cuba, who had received information from dissidents inside Cuba that Soviet troops had arrived in Cuba in early August and were seen working "in all probability on or near a missile base" and who passed this information to Keating on a trip to Washington in early October.[56] Air Force General Curtis LeMay presented a pre-invasion bombing plan to Kennedy in September, and spy flights and minor military harassment from US forces at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base were the subject of continual Cuban diplomatic complaints to the US government.[15]

The first consignment of Soviet R-12 missiles arrived on the night of 8 September, followed by a second on 16 September. The R-12 was a medium-range ballistic missile, capable of carrying a thermonuclear warhead.[57] It was a single-stage, road-transportable, surface-launched, storable liquid propellant fuelled missile that could deliver a megaton-class nuclear weapon.[citation needed] The Soviets were building nine sites—six for R-12 medium-range missiles (NATO designation SS-4 Sandal) with an effective range of 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) and three for R-14 intermediate-range ballistic missiles (NATO designation SS-5 Skean) with a maximum range of 4,500 kilometres (2,800 mi).[citation needed]

On 7 October, Cuban President Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado spoke at the UN General Assembly: "If... we are attacked, we will defend ourselves. I repeat, we have sufficient means with which to defend ourselves; we have indeed our inevitable weapons, the weapons, which we would have preferred not to acquire, and which we do not wish to employ."[58] On 11 October in another Senate speech, Sen Keating reaffirmed his earlier warning of 31 August and stated that, "Construction has begun on at least a half dozen launching sites for intermediate range tactical missiles."[59]

The Cuban leadership was further upset when on 20 September, the US Senate approved Joint Resolution 230, which expressed the US was determined "to prevent in Cuba the creation or use of an externally-supported military capability endangering the security of the United States".[60][61] On the same day, the US announced a major military exercise in the Caribbean, PHIBRIGLEX-62, which Cuba denounced as a deliberate provocation and proof that the US planned to invade Cuba.[61][62][unreliable source?]

The Soviet leadership believed, based on its perception of Kennedy's lack of confidence during the Bay of Pigs Invasion, that he would avoid confrontation and accept the missiles as a fait accompli.[17]: 1 On 11 September, the Soviet Union publicly warned that a US attack on Cuba or on Soviet ships that were carrying supplies to the island would mean war.[15] The Soviets continued the Maskirovka program to conceal their actions in Cuba. They repeatedly denied that the weapons being brought into Cuba were offensive in nature. On 7 September, Soviet Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin assured United States Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson that the Soviet Union was supplying only defensive weapons to Cuba. On 11 September, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS: Telegrafnoe Agentstvo Sovetskogo Soyuza) announced that the Soviet Union had no need or intention to introduce offensive nuclear missiles into Cuba. On 13 October, Dobrynin was questioned by former Undersecretary of State Chester Bowles about whether the Soviets planned to put offensive weapons in Cuba. He denied any such plans.[61] On 17 October, Soviet embassy official Georgy Bolshakov brought President Kennedy a personal message from Khrushchev reassuring him that "under no circumstances would surface-to-surface missiles be sent to Cuba."[61]: 494

Missiles reported

editThe missiles in Cuba allowed the Soviets to effectively target most of the Continental US. The planned arsenal was forty launchers. The Cuban populace readily noticed the arrival and deployment of the missiles and hundreds of reports reached Miami. US intelligence received countless reports, many of dubious quality or even laughable, most of which could be dismissed as describing defensive missiles.[63][64][65]

Only five reports bothered the analysts. They described large trucks passing through towns at night that were carrying very long canvas-covered cylindrical objects that could not make turns through towns without backing up and maneuvering. Defensive missile transporters, it was believed, could make such turns without undue difficulty. The reports could not be satisfactorily dismissed.[66]

Aerial confirmation

editThe United States had been sending U-2 surveillance over Cuba since the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.[67] The first issue that led to a pause in reconnaissance flights took place on 30 August, when a U-2 operated by the US Air Force's Strategic Air Command flew over Sakhalin Island in the Soviet Far East by mistake. The Soviets lodged a protest and the US apologized. Nine days later, a Taiwanese-operated U-2[68][69] was lost over western China to an SA-2 surface-to-air missile (SAM). US officials were worried that one of the Cuban or Soviet SAMs in Cuba might shoot down a CIA U-2, initiating another international incident. In a meeting with members of the Committee on Overhead Reconnaissance (COMOR) on 10 September, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy heavily restricted further U-2 flights over Cuban airspace. The resulting lack of coverage over the island for the next five weeks became known to historians as the "Photo Gap".[70] No significant U-2 coverage was achieved over the interior of the island. US officials attempted to use a Corona photo-reconnaissance satellite to obtain coverage over reported Soviet military deployments, but imagery acquired over western Cuba by a Corona KH-4 mission on October 1 was heavily covered by clouds and haze and failed to provide any usable intelligence.[71] At the end of September, Navy reconnaissance aircraft photographed the Soviet ship Kasimov, with large crates on its deck the size and shape of Il-28 jet bomber fuselages.[34]

In September 1962, analysts from the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) noticed that Cuban surface-to-air missile sites were arranged in a pattern similar to those used by the Soviet Union to protect its ICBM bases, leading DIA to lobby for the resumption of U-2 flights over the island.[72] Although in the past the flights had been conducted by the CIA, pressure from the Defense Department led to that authority being transferred to the Air Force.[34] Following the loss of a CIA U-2 over the Soviet Union in May 1960, it was thought that if another U-2 were shot down, an Air Force aircraft arguably being used for a legitimate military purpose would be easier to explain than a CIA flight.

When the reconnaissance missions were reauthorized on 9 October, poor weather kept the planes from flying. The US first obtained U-2 photographic evidence of the missiles on 14 October, when a U-2 flight piloted by Major Richard Heyser took 928 pictures on a path selected by DIA analysts, capturing images of what turned out to be an SS-4 construction site at San Cristóbal, Pinar del Río Province (now in Artemisa Province), in western Cuba.[73]

President notified

editOn 15 October, the CIA's National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) reviewed the U-2 photographs and identified objects that they interpreted as medium range ballistic missiles. This identification was made, in part, on the strength of reporting provided by Oleg Penkovsky, a double agent in the GRU working for the CIA and MI6. Although he provided no direct reports of the Soviet missile deployments to Cuba, technical and doctrinal details of Soviet missile regiments that had been provided by Penkovsky in the months and years prior to the Crisis helped NPIC analysts correctly identify the missiles on U-2 imagery.[74]

That evening, the CIA notified the Department of State and at 8:30 pm EDT, Bundy chose to wait until the next morning to tell the President. McNamara was briefed at midnight. The next morning, Bundy met with Kennedy and showed him the U-2 photographs and briefed him on the CIA's analysis of the images.[75] At 6:30 pm EDT, Kennedy convened a meeting of the nine members of the National Security Council and five other key advisers,[76] in a group he formally named the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM) after the fact on 22 October by National Security Action Memorandum 196.[77] Without informing the members of EXCOMM, President Kennedy tape-recorded all of their proceedings, and Sheldon M. Stern, head of the Kennedy library transcribed some of them.[78][79]

On 16 October, President Kennedy notified Attorney General Robert Kennedy that he was convinced the Soviets were placing missiles in Cuba and it was a legitimate threat. This made the threat of nuclear destruction by two world superpowers a reality. Robert Kennedy responded by contacting the Soviet Ambassador, Anatoly Dobrynin. Robert Kennedy expressed his "concern about what was happening" and Dobrynin "was instructed by Soviet Chairman Nikita S. Khrushchev to assure President Kennedy that there would be no ground-to-ground missiles or offensive weapons placed in Cuba". Khrushchev further assured Kennedy that the Soviet Union had no intention of "disrupting the relationship of our two countries" despite the photo evidence presented before President Kennedy.[80]

Responses considered

editThe US had no plan in place because until recently its intelligence had been convinced that the Soviets would never install nuclear missiles in Cuba. EXCOMM discussed several possible courses of action:[81]

- Do nothing: American vulnerability to Soviet missiles was not new.

- Diplomacy: Use diplomatic pressure to get the Soviet Union to remove the missiles.

- Secret approach: Offer Castro the choice of splitting with the Soviets or being invaded.

- Invasion: Full-force invasion of Cuba and overthrow of Castro.

- Air strike: Use the US Air Force to attack all known missile sites.

- Blockade: Use the US Navy to block any missiles from arriving in Cuba.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff unanimously agreed that a full-scale attack and invasion was the only solution. They believed that the Soviets would not attempt to stop the US from conquering Cuba. Kennedy was skeptical:

They, no more than we, can let these things go by without doing something. They can't, after all their statements, permit us to take out their missiles, kill a lot of Russians, and then do nothing. If they don't take action in Cuba, they certainly will in Berlin.[82]

Kennedy concluded that attacking Cuba by air would signal the Soviets to presume "a clear line" to conquer Berlin. Kennedy also believed that US allies would think of the country as "trigger-happy cowboys" who lost Berlin because they could not peacefully resolve the Cuban situation.[83]

The EXCOMM then discussed the effect on the strategic balance of power, both political and military. The Joint Chiefs of Staff believed that the missiles would seriously alter the military balance, but McNamara disagreed. An extra 40, he reasoned, would make little difference to the overall strategic balance. The US already had approximately 5,000 strategic warheads,[84] but the Soviet Union had only 300. McNamara concluded that the Soviets having 340 would not therefore substantially alter the strategic balance. In 1990, he reiterated that "it made no difference.... The military balance wasn't changed. I didn't believe it then, and I don't believe it now."[85]

The EXCOMM agreed that the missiles would affect the political balance. Kennedy had explicitly promised the American people less than a month before the crisis that "if Cuba should possess a capacity to carry out offensive actions against the United States... the United States would act."[86]: 674–681 Further, US credibility among its allies and people would be damaged if the Soviet Union appeared to redress the strategic imbalance by placing missiles in Cuba. Kennedy explained after the crisis that "it would have politically changed the balance of power. It would have appeared to, and appearances contribute to reality."[87]

On 18 October, Kennedy met with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko, who claimed the weapons were for defensive purposes only. Not wanting to expose what he already knew and to avoid panicking the American public,[88] Kennedy did not reveal that he was already aware of the missile buildup.[89]

Operational plans

editTwo Operational Plans (OPLAN) were considered. OPLAN 316 envisioned a full invasion of Cuba by Army and Marine units, supported by the Navy, following Air Force and naval airstrikes. Army units in the US would have had trouble fielding mechanised and logistical assets, and the US Navy could not supply enough amphibious shipping to transport even a modest armoured contingent from the Army.

OPLAN 312, primarily an Air Force and Navy carrier operation, was designed with enough flexibility to do anything from engaging individual missile sites to providing air support for OPLAN 316's ground forces.[90]

Blockade

editKennedy met with members of EXCOMM and other top advisers throughout 21 October, considering two remaining options: an air strike primarily against the Cuban missile bases or a naval blockade of Cuba.[89] A full-scale invasion was not the administration's first option. McNamara supported the naval blockade as a strong but limited military action that left the US in control. The term "blockade" was problematic – according to international law, a blockade is an act of war, but the Kennedy administration did not think that the Soviets would be provoked to attack by a mere blockade.[92] Additionally, legal experts at the State Department and Justice Department concluded that a declaration of war could be avoided if another legal justification, based on the Rio Treaty for defence of the Western Hemisphere, was obtained from a resolution by a two-thirds vote from the members of the Organization of American States (OAS).[93]

Admiral George Anderson, Chief of Naval Operations wrote a position paper that helped Kennedy to differentiate between what they termed a "quarantine"[94] of offensive weapons and a blockade of all materials, claiming that a classic blockade was not the original intention. Since it would take place in international waters, Kennedy obtained the approval of the OAS for military action under the hemispheric defence provisions of the Rio Treaty:

Latin American participation in the quarantine now involved two Argentine destroyers which were to report to the US Commander South Atlantic [COMSOLANT] at Trinidad on November 9. An Argentine submarine and a Marine battalion with lift were available if required. In addition, two Venezuelan destroyers (Destroyers ARV D-11 Nueva Esparta" and "ARV D-21 Zulia") and one submarine (Caribe) had reported to COMSOLANT, ready for sea by November 2. The Government of Trinidad and Tobago offered the use of Chaguaramas Naval Base to warships of any OAS nation for the duration of the "quarantine". The Dominican Republic had made available one escort ship. Colombia was reported ready to furnish units and had sent military officers to the US to discuss this assistance. The Argentine Air Force informally offered three SA-16 aircraft in addition to forces already committed to the "quarantine" operation.[95]

This initially was to involve a naval blockade against offensive weapons within the framework of the Organization of American States and the Rio Treaty. Such a blockade might be expanded to cover all types of goods and air transport. The action was to be backed up by surveillance of Cuba. The CNO's scenario was followed closely in later implementing the "quarantine."

On 19 October, the EXCOMM formed separate working groups to examine the air strike and blockade options, and by the afternoon most support in the EXCOMM had shifted to a blockade. Reservations about the plan continued to be voiced as late as 21 October, the paramount concern being that once the blockade was put into effect the Soviets would rush to complete some of the missiles. Consequently, the US could find itself bombing operational missiles if the blockade did not force Khrushchev to remove the missiles already on the island.[96]: 99–101

Speech to the nation

editAt 3:00 pm EDT on 22 October, President Kennedy formally established the executive committee (EXCOMM) with National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 196. At 5:00 pm, he met with Congressional leaders, who contentiously opposed a blockade and demanded a stronger response. In Moscow, US Ambassador Foy D. Kohler briefed Khrushchev on the pending blockade and Kennedy's speech to the nation. Ambassadors around the world gave notice to non-Eastern Bloc leaders. Before the speech, US delegations met with Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, French President Charles de Gaulle and Secretary-General of the Organization of American States, José Antonio Mora to brief them on this intelligence and the US's proposed response. All were supportive of the US position. Over the course of the crisis, Kennedy had daily telephone conversations with Macmillan, who was publicly supportive of US actions.[98]

Shortly before his speech, Kennedy telephoned former President Dwight Eisenhower.[99] Kennedy's conversation with the former president also revealed that the two had been consulting during the Cuban Missile Crisis.[100] The two also anticipated that Khrushchev would respond to the Western world in a manner similar to his response during the Suez Crisis, and would possibly wind up trading off[clarification needed] Berlin.[100]

At 7:00 pm EDT on 22 October, Kennedy delivered a nationwide televised address on all of the major networks announcing the discovery of the missiles. He noted:

It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.[101]

Kennedy described the administration's plan:

To halt this offensive buildup, a strict quarantine on all offensive military equipment under shipment to Cuba is being initiated. All ships of any kind bound for Cuba, from whatever nation or port, will, if found to contain cargoes of offensive weapons, be turned back. This quarantine will be extended, if needed, to other types of cargo and carriers. We are not at this time, however, denying the necessities of life as the Soviets attempted to do in their Berlin blockade of 1948.[101]

During the speech, a directive went out to all US forces worldwide, placing them on DEFCON 3. The heavy cruiser USS Newport News was the designated flagship for the blockade,[94] with USS Leary as Newport News's destroyer escort.[95] Kennedy's speech writer Ted Sorensen stated in 2007 that the address to the nation was "Kennedy's most important speech historically, in terms of its impact on our planet."[102]

Crisis deepens

editAt 11:24 am EDT on 24 October, a cable from US Secretary of State George Ball to the US Ambassadors in Turkey and NATO notified them that they were considering making an offer to withdraw the missiles from Italy and Turkey, in exchange for the Soviet withdrawal from Cuba. Turkish officials replied that they would "deeply resent" any trade involving the US missile presence in their country.[105] One day later, on the morning of 25 October, American journalist Walter Lippmann proposed the same thing in his syndicated column. Castro reaffirmed Cuba's right to self-defense and said that all of its weapons were defensive and Cuba would not allow an inspection.[15]

International response

editThree days after Kennedy's speech, the Chinese People's Daily announced that "650,000,000 Chinese men and women were standing by the Cuban people."[106] In West Germany, newspapers supported the US response by contrasting it with the weak American actions in the region during the preceding months. They also expressed some fear that the Soviets might retaliate in Berlin. In France on 23 October, the crisis made the front page of all the daily newspapers. The next day, an editorial in Le Monde expressed doubt about the authenticity of the CIA's photographic evidence. Two days later, after a visit by a high-ranking CIA agent, the newspaper accepted the validity of the photographs. In the 29 October issue of Le Figaro, Raymond Aron wrote in support of the American response.[107] On 24 October, Pope John XXIII sent a message to the Soviet embassy in Rome, to be transmitted to the Kremlin, in which he voiced his concern for peace. In this message he stated, "We beg all governments not to remain deaf to this cry of humanity. That they do all that is in their power to save peace."[108]

Soviet broadcast and communications

editThe crisis continued unabated, and on the evening of 24 October, the Soviet TASS news agency broadcast a telegram from Khrushchev to Kennedy, in which Khrushchev warned that the United States' "outright piracy" would lead to war.[109] Khrushchev then sent at 9:24 pm a telegram to Kennedy, which was received at 10:52 pm EDT. Khrushchev stated, "if you weigh the present situation with a cool head without giving way to passion, you will understand that the Soviet Union cannot afford not to decline the despotic demands of the USA" and that the Soviet Union viewed the blockade as "an act of aggression", and their ships would be instructed to ignore it.[104] After 23 October, Soviet communications with the US increasingly showed indications of having been rushed. Undoubtedly a product of pressure, it was not uncommon for Khrushchev to repeat himself and to send messages lacking basic editing.[110] With President Kennedy making his aggressive intentions of a possible airstrike followed by an invasion on Cuba known, Khrushchev rapidly sought a diplomatic compromise. Communications between the two superpowers had entered into a unique and revolutionary period; with the newly developed threat of mutual destruction through the deployment of nuclear weapons, diplomacy now demonstrated how power and coercion could dominate negotiations.[clarification needed][111]

US alert level raised

editThe US requested an emergency meeting of the United Nations Security Council on 25 October. US Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson confronted Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin in an emergency meeting of the Security Council, challenging him to admit the existence of the missiles. Ambassador Zorin refused to answer. At 10:00 pm EDT the next day, the US raised the readiness level of Strategic Air Command (SAC) forces to DEFCON 2. For the only confirmed time in US history, B-52 bombers went on continuous airborne alert, and B-47 medium bombers were dispersed to various military and civilian airfields and made ready to take off, fully equipped, on 15 minutes' notice.[112] One-eighth of SAC's 1,436 bombers were on airborne alert, and some 145 intercontinental ballistic missiles stood on ready alert, some of which targeted Cuba.[113] Air Defense Command (ADC) redeployed 161 nuclear-armed interceptors to 16 dispersal fields within nine hours, with one third maintaining 15-minute alert status.[90] Twenty-three nuclear-armed B-52s were sent to orbit points within striking distance of the Soviet Union so it would believe that the US was serious.[114] Jack J. Catton later estimated that about 80 per cent of SAC's planes were ready for launch during the crisis; David A. Burchinal recalled that, by contrast:[115]

the Russians were so thoroughly stood down, and we knew it. They didn't make any move. They did not increase their alert; they did not increase any flights, or their air defense posture. They didn't do a thing, they froze in place. We were never further from nuclear war than at the time of Cuba, never further.

By 22 October, Tactical Air Command (TAC) had 511 fighters, plus supporting tankers and reconnaissance aircraft, deployed to face Cuba on one-hour alert status. TAC and the Military Air Transport Service had problems. The concentration of aircraft in Florida strained command and support echelons, which faced critical undermanning in security, armaments, and communications; the absence of initial authorization for war-reserve stocks of conventional munitions forced TAC to scrounge; and the lack of airlift assets to support a major airborne drop necessitated the call-up of 24 reserve squadrons.[90]

On 25 October at 1:45 am EDT, Kennedy responded to Khrushchev's telegram by stating that the US was forced into action after receiving repeated assurances that no offensive missiles were being placed in Cuba, and when the assurances proved to be false, the deployment "required the responses I have announced.... I hope that your government will take necessary action to permit a restoration of the earlier situation."

Blockade challenged

editAt 7:15 am EDT on 25 October, USS Essex and USS Gearing attempted to intercept Bucharest but failed to do so. Fairly certain that the tanker did not contain any military material, the US allowed it through the blockade. Later that day, at 5:43 pm, the commander of the blockade effort ordered the destroyer USS Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. to intercept and board the Lebanese freighter Marucla. That took place the next day, and Marucla was cleared through the blockade after its cargo was checked.[116]

At 5:00 pm EDT on 25 October, William Clements announced that the missiles in Cuba were still actively being worked on. That report was later verified by a CIA report that suggested there had been no slowdown at all. In response, Kennedy issued Security Action Memorandum 199, authorizing the loading of nuclear weapons onto aircraft under the command of SACEUR, which had the duty of carrying out first air strikes on the Soviet Union. Kennedy claimed that the blockade had succeeded when the USSR turned back fourteen ships presumably carrying offensive weapons.[117] The first indication of this came from a report from the British GCHQ sent to the White House Situation Room containing intercepted communications from Soviet ships reporting their positions. On 24 October, Kislovodsk, a Soviet cargo ship, reported a position north-east of where it had been 24 hours earlier indicating it had "discontinued" its voyage and turned back towards the Baltic. The next day, reports showed more ships originally bound for Cuba had altered their course.[118]

Raising the stakes

editThe next morning, 26 October, Kennedy informed the EXCOMM that he believed only an invasion would remove the missiles from Cuba. He was persuaded to give the matter time and continue with both military and diplomatic pressure. He agreed and ordered the low-level flights over the island to be increased from two per day to once every two hours. He also ordered a crash program to institute a new civil government in Cuba if an invasion went ahead.[citation needed]

At this point, the crisis was ostensibly at a stalemate. The Soviets had shown no indication that they would back down and had made public media and private inter-governmental statements to that effect. The US had no reason to believe otherwise and was in the early stages of preparing for an invasion, along with a nuclear strike on the Soviet Union if it responded militarily, which the US assumed it would.[119] Kennedy had no intention of keeping these plans a secret; with an array of Cuban and Soviet spies forever present, Khrushchev was quickly made aware of this looming danger.

The implicit threat of air strikes on Cuba followed by invasion allowed the United States to exert pressure in future talks. It was the possibility of military action that played an influential role in accelerating Khrushchev's proposal for a compromise.[110] Throughout the closing stages of October, Soviet communications to the United States indicated increasing defensiveness. Khrushchev's increasing tendency to use poorly phrased and ambiguous communications throughout the compromise negotiations conversely increased United States confidence and clarity in messaging. Leading Soviet figures consistently failed to mention that only the Cuban government could agree to inspections of the territory and continually made arrangements relating to Cuba without the knowledge of Fidel Castro himself. According to Dean Rusk, Khrushchev "blinked"; he began to panic from the consequences of his own plan, and this was reflected in the tone of Soviet messages. This allowed the US to largely dominate negotiations in late October.[110]

The escalating situation also led Khrushchev to abandon plans for a potential Warsaw Pact invasion of Albania, which was being discussed in the Eastern Bloc following the Vlora incident the year prior.[120]

Secret negotiations

editAt 1:00 pm EDT on 26 October, John A. Scali of ABC News had lunch with Aleksandr Fomin, the cover name of Alexander Feklisov, the KGB station chief in Washington, at Fomin's request. Following the instructions of the Politburo of the CPSU,[121] Fomin noted, "War seems about to break out." He asked Scali to use his contacts to talk to his "high-level friends" at the State Department to see if the US would be interested in a diplomatic solution. He suggested that the language of the deal would contain an assurance from the Soviet Union to remove the weapons under UN supervision and that Castro would publicly announce that he would not accept such weapons again in exchange for a public statement by the US that it would not invade Cuba.[122] The US responded by asking the Brazilian government to pass a message to Castro that the US would be "unlikely to invade" if the missiles were removed.[105]

Mr. President, we and you ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be necessary to cut that knot, and what that would mean is not for me to explain to you, because you yourself understand perfectly of what terrible forces our countries dispose.

Consequently, if there is no intention to tighten that knot and thereby to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot. We are ready for this.

— Letter From Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy, 26 October 1962[123]

At 6:00 pm EDT on 26 October, the State Department started receiving a message that appeared to be written personally by Khrushchev. It was Saturday 2:00 am in Moscow. The long letter took several minutes to arrive, and it took translators additional time to translate and transcribe it.[105]

Robert F. Kennedy described the letter as "very long and emotional". Khrushchev reiterated the basic outline that had been stated to Scali earlier in the day: "I propose: we, for our part, will declare that our ships bound for Cuba are not carrying any armaments. You will declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its troops and will not support any other forces which might intend to invade Cuba. Then the necessity of the presence of our military specialists in Cuba will disappear." At 6:45 pm EDT, news of Fomin's offer to Scali was finally heard and was interpreted as a "set up" for the arrival of Khrushchev's letter. The letter was then considered official and accurate, although it was later learned that Fomin was almost certainly operating of his own accord without official backing. Additional study of the letter was ordered and continued into the night.[105]

Crisis continues

editDirect aggression against Cuba would mean nuclear war. The Americans speak about such aggression as if they did not know or did not want to accept this fact. I have no doubt they would lose such a war.

— Che Guevara, October 1962[124]

Castro, on the other hand, was convinced that an invasion of Cuba was soon at hand, and on 26 October, he sent a telegram to Khrushchev that appeared to call for a pre-emptive nuclear strike on the US in case of attack. In a 2010 interview, Castro expressed regret about his 1962 stance on first use: "After I've seen what I've seen, and knowing what I know now, it wasn't worth it at all."[125] Castro also ordered all anti-aircraft weapons in Cuba to fire on any US aircraft;[126] previous orders had been to fire only on groups of two or more. At 6:00 am EDT on 27 October, the CIA delivered a memo reporting that three of the four missile sites at San Cristobal and both sites at Sagua la Grande appeared to be fully operational. It also noted that the Cuban military continued to organise for action but was under order not to initiate action unless attacked.[citation needed]

At 9:00 am EDT on 27 October, Radio Moscow began broadcasting a message from Khrushchev. Contrary to the letter of the night before, the message offered a new trade: the missiles on Cuba would be removed in exchange for the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy and Turkey. At 10:00 am EDT, the executive committee met again to discuss the situation and came to the conclusion that the change in the message was because of internal debate between Khrushchev and other party officials in the Kremlin.[127] Kennedy realised that he would be in an "insupportable position if this becomes Khrushchev's proposal" because the missiles in Turkey were not militarily useful and were being removed anyway and "It's gonna – to any man at the United Nations or any other rational man, it will look like a very fair trade." Bundy explained why Khrushchev's public acquiescence could not be considered: "The current threat to peace is not in Turkey, it is in Cuba."[128]

McNamara noted that another tanker, the Grozny, was about 600 miles (970 km) out and should be intercepted. He also noted that they had not made the Soviets aware of the blockade line and suggested relaying that information to them via U Thant at the United Nations.[129]

While the meeting progressed, at 11:03 am EDT a new message began to arrive from Khrushchev. The message stated, in part:

"You are disturbed over Cuba. You say that this disturbs you because it is ninety-nine miles by sea from the coast of the United States of America. But... you have placed destructive missile weapons, which you call offensive, in Italy and Turkey, literally next to us.... I therefore make this proposal: We are willing to remove from Cuba the means which you regard as offensive.... Your representatives will make a declaration to the effect that the United States... will remove its analogous means from Turkey... and after that, persons entrusted by the United Nations Security Council could inspect on the spot the fulfillment of the pledges made."

The executive committee continued to meet through the day.

Throughout the crisis, Turkey had repeatedly stated that it would be upset if the Jupiter missiles were removed. Italy's Prime Minister Amintore Fanfani, who was also Foreign Minister ad interim, offered to allow withdrawal of the missiles deployed in Apulia as a bargaining chip. He gave the message to one of his most trusted friends, Ettore Bernabei, general manager of RAI-TV, to convey to Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Bernabei was in New York to attend an international conference on satellite TV broadcasting.

On the morning of 27 October, a U-2F (the third CIA U-2A, modified for air-to-air refuelling) piloted by USAF Major Rudolf Anderson,[130] departed its forward operating location at McCoy AFB, Florida. At approximately 12:00 pm EDT, the aircraft was struck by an SA-2 surface-to-air missile launched from Cuba. The aircraft crashed, and Anderson was killed. Stress in negotiations between the Soviets and the US intensified; only later was it assumed that the decision to fire the missile was made locally by an undetermined Soviet commander, acting on his own authority. Later that day, at about 3:41 pm EDT, several US Navy RF-8A Crusader aircraft, on low-level photo-reconnaissance missions, were fired upon.

At 4:00 pm EDT, Kennedy recalled members of EXCOMM to the White House and ordered that a message should immediately be sent to U Thant asking the Soviets to suspend work on the missiles while negotiations were carried out. During the meeting, General Maxwell Taylor delivered the news that the U-2 had been shot down. Kennedy had earlier claimed he would order an attack on such sites if fired upon, but he decided to not act unless another attack was made.

On 27 October Bobby Kennedy relayed a message to the Soviet Ambassador that President Kennedy was under pressure from the military to use force against Cuba and that "an irreversible chain of events could occur against his will" as "the president is not sure that the military will not overthrow him and seize power", he therefore implored Khrushchev to accept Kennedy's proposed agreement.[131]

On 28 October 1962, Khrushchev told his son Sergei that the shooting down of Anderson's U-2 was by the "Cuban military at the direction of Raúl Castro".[132][133][134][135]

Forty years later, McNamara said:

We had to send a U-2 over to gain reconnaissance information on whether the Soviet missiles were becoming operational. We believed that if the U-2 was shot down that—the Cubans didn't have capabilities to shoot it down, the Soviets did—we believed if it was shot down, it would be shot down by a Soviet surface-to-air-missile unit, and that it would represent a decision by the Soviets to escalate the conflict. And therefore, before we sent the U-2 out, we agreed that if it was shot down we wouldn't meet, we'd simply attack. It was shot down on Friday.... Fortunately, we changed our mind, we thought "Well, it might have been an accident, we won't attack." Later we learned that Khrushchev had reasoned just as we did: we send over the U-2, if it was shot down, he reasoned we would believe it was an intentional escalation. And therefore, he issued orders to Pliyev, the Soviet commander in Cuba, to instruct all of his batteries not to shoot down the U-2.[note 1][136]

Daniel Ellsberg said that Robert Kennedy (RFK) told him in 1964 that after the U-2 was shot down and the pilot killed, he (RFK) told Soviet ambassador Dobrynin, "You have drawn first blood ... . [T]he president had decided against advice ... not to respond militarily to that attack, but he [Dobrynin] should know that if another plane was shot at, ... we would take out all the SAMs and antiaircraft ... . And that would almost surely be followed by an invasion."[137]

Drafting response

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Emissaries sent by both Kennedy and Khrushchev agreed to meet at the Yenching Palace Chinese restaurant in the Cleveland Park neighbourhood of Washington, DC, on Saturday evening, 27 October.[138] Kennedy suggested to take Khrushchev's offer to trade away the missiles. Unknown to most members of the EXCOMM, but with the support of his brother the president, Robert Kennedy had been meeting with the Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin in Washington to discover whether the intentions were genuine.[139] The EXCOMM was generally against the proposal because it would undermine NATO's authority, and the Turkish government had repeatedly stated it was against any such trade.

As the meeting progressed, a new plan emerged, and Kennedy was slowly persuaded. The new plan called for him to ignore the latest message and instead to return to Khrushchev's earlier one. Kennedy was initially hesitant, feeling that Khrushchev would no longer accept the deal because a new one had been offered, but Llewellyn Thompson argued that it was still possible.[96]: 135–56 White House Special Counsel and Adviser Ted Sorensen and Robert Kennedy left the meeting and returned 45 minutes later, with a draft letter to that effect. The President made several changes, had it typed, and sent it.

After the EXCOMM meeting, a smaller meeting continued in the Oval Office. The group argued that the letter should be underscored with an oral message to Dobrynin that stated that if the missiles were not withdrawn, military action would be used to remove them. Rusk added one proviso that no part of the language of the deal would mention Turkey, but there would be an understanding that the missiles would be removed "voluntarily" in the immediate aftermath. The president agreed, and the message was sent.

At Rusk's request, Fomin and Scali met again. Scali asked why the two letters from Khrushchev were so different, and Fomin claimed it was because of "poor communications". Scali replied that the claim was not credible and shouted that he thought it was a "stinking double cross". He went on to claim that an invasion was only hours away, and Fomin stated that a response to the US message was expected from Khrushchev shortly and urged Scali to tell the State Department that no treachery was intended. Scali said that he did not think anyone would believe him, but he agreed to deliver the message. The two went their separate ways, and Scali immediately typed out a memo for the EXCOMM.[140]

Within the US establishment, it was well understood that ignoring the second offer and returning to the first put Khrushchev in a terrible position. Military preparations continued, and all active duty Air Force personnel were recalled to their bases for possible action. Robert Kennedy later recalled the mood: "We had not abandoned all hope, but what hope there was now rested with Khrushchev's revising his course within the next few hours. It was a hope, not an expectation. The expectation was military confrontation by Tuesday [30 October], and possibly tomorrow [29 October] ...."[140]

At 8:05 pm EDT, the letter drafted earlier in the day was delivered. The message read, "As I read your letter, the key elements of your proposals—which seem generally acceptable as I understand them—are as follows: 1) You would agree to remove these weapons systems from Cuba under appropriate United Nations observation and supervision; and undertake, with suitable safe-guards, to halt the further introduction of such weapon systems into Cuba. 2) We, on our part, would agree—upon the establishment of adequate arrangements through the United Nations, to ensure the carrying out and continuation of these commitments (a) to remove promptly the quarantine measures now in effect and (b) to give assurances against the invasion of Cuba." The letter was also released directly to the press to ensure it could not be "delayed".[141] With the letter delivered, a deal was on the table. As Robert Kennedy noted, there was little expectation it would be accepted. At 9:00 pm EDT, the EXCOMM met again to review the actions for the following day. Plans were drawn up for air strikes on the missile sites as well as other economic targets, notably petroleum storage. McNamara stated that they had to "have two things ready: a government for Cuba, because we're going to need one; and secondly, plans for how to respond to the Soviet Union in Europe, because sure as hell they're going to do something there".[142]

At 12:12 am EDT, on 27 October, the US informed its NATO allies that "the situation is growing shorter.... the United States may find it necessary within a very short time in its interest and that of its fellow nations in the Western Hemisphere to take whatever military action may be necessary." To add to the concern, at 6:00 am, the CIA reported that all missiles in Cuba were ready for action.

On 27 October, Khrushchev also received a letter from Castro, what is now known as the Armageddon Letter (dated the day before), which was interpreted as urging the use of nuclear force in the event of an attack on Cuba:[143] "I believe the imperialists' aggressiveness is extremely dangerous and if they actually carry out the brutal act of invading Cuba in violation of international law and morality, that would be the moment to eliminate such danger forever through an act of clear legitimate defense, however harsh and terrible the solution would be," Castro wrote.[144]

Averted nuclear launch

editLater that same day, what the White House later called "Black Saturday", the US Navy dropped a series of "signalling" depth charges ("practice" depth charges the size of hand grenades)[145] on a Soviet submarine (B-59) at the blockade line, unaware that it was armed with a nuclear-tipped torpedo with orders that allowed it to be used if the submarine was damaged by depth charges or surface fire.[146] As the submarine was too deep to monitor any radio traffic,[147][148] the captain of the B-59, Valentin Grigoryevich Savitsky, assumed after live ammunition fire at his submarine, that a war had already started and wanted to launch a nuclear torpedo.[149][better source needed] The decision to launch these normally only required the agreement of the ship's commanding officer and political officer. However, the commander of the submarine flotilla, Vasily Arkhipov, was aboard B-59 and so he also had to agree. Arkhipov objected and so the nuclear launch was narrowly averted. (These events only publicly became known in 2002. See Submarine close call.)

On the same day a U-2 spy plane made an accidental, unauthorised 90-minute overflight of the Soviet Union's far eastern coast.[150] The Soviets responded by scrambling MiG fighters from Wrangel Island; in turn, the Americans launched F-102 fighters armed with nuclear air-to-air missiles over the Bering Sea.[151]

Resolution

editOn Saturday, 27 October, after much deliberation between the Soviet Union and Kennedy's cabinet, Kennedy secretly agreed to remove all missiles set in Turkey and possibly southern Italy, the former on the border of the Soviet Union, in exchange for Khrushchev removing all missiles in Cuba.[152][153][154][155][156] There is some dispute as to whether removing the missiles from Italy was part of the secret agreement. Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs that it was, and when the crisis had ended McNamara gave the order to dismantle the missiles in both Italy and Turkey.[157]

At this point, Khrushchev knew things the US did not. First, that the shooting down of the U-2 by a Soviet missile violated direct orders from Moscow, and Cuban anti-aircraft fire against other US reconnaissance aircraft also violated direct orders from Khrushchev to Castro.[158] Second, the Soviets already had 162 nuclear warheads on Cuba that the US did not then believe were there.[159] Third, the Soviets and Cubans on the island would almost certainly have responded to an invasion by using those nuclear weapons, even though Castro believed that every human in Cuba would likely die as a result.[160] Khrushchev also knew but may not have considered the fact that he had submarines armed with nuclear weapons that the US Navy may not have known about.

Khrushchev knew he was losing control. President Kennedy had been told in early 1961 that a nuclear war would likely kill a third of humanity, with most or all of those deaths concentrated in the US, the USSR, Europe and China;[161] Khrushchev may well have received similar reports from his military.

With this background, when Khrushchev heard Kennedy's threats relayed by Robert Kennedy to Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin, he immediately drafted his acceptance of Kennedy's latest terms from his dacha without involving the Politburo, as he had previously, and had them immediately broadcast over Radio Moscow, which he believed the US would hear. In that broadcast at 9:00 am EST, on 28 October, Khrushchev stated that "the Soviet government, in addition to previously issued instructions on the cessation of further work at the building sites for the weapons, has issued a new order on the dismantling of the weapons which you describe as 'offensive' and their crating and return to the Soviet Union."[162][163][164] At 10:00 am on 28 October, Kennedy first learned of Khrushchev's solution to the crisis with the US removing the 15 Jupiters in Turkey and the Soviets would remove the rockets from Cuba. Khrushchev had made the offer in a public statement for the world to hear. Despite almost solid opposition from his senior advisers, Kennedy quickly embraced the Soviet offer. "This is a pretty good play of his," Kennedy said, according to a tape recording that he made secretly of the Cabinet Room meeting. Kennedy had deployed the Jupiters in March 1962, causing a stream of angry outbursts from Khrushchev. "Most people will think this is a rather even trade and we ought to take advantage of it," Kennedy said. Vice President Lyndon Johnson was the first to endorse the missile swap but others continued to oppose the offer. Finally, Kennedy ended the debate. "We can't very well invade Cuba with all its toil and blood," Kennedy said, "when we could have gotten them out by making a deal on the same missiles on Turkey. If that's part of the record, then you don't have a very good war."[165]

Kennedy immediately responded to Khrushchev's letter, issuing a statement calling it "an important and constructive contribution to peace".[164] He continued this with a formal letter:

I consider my letter to you of October twenty-seventh and your reply of today as firm undertakings on the part of both our governments which should be promptly carried out.... The US will make a statement in the framework of the Security Council in reference to Cuba as follows: it will declare that the United States of America will respect the inviolability of Cuban borders, its sovereignty, that it take the pledge not to interfere in internal affairs, not to intrude themselves and not to permit our territory to be used as a bridgehead for the invasion of Cuba, and will restrain those who would plan to carry an aggression against Cuba, either from US territory or from the territory of other countries neighboring to Cuba.[164][166]: 103

Kennedy's planned statement would also contain suggestions he had received from his adviser Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in a "Memorandum for the President" describing the "Post Mortem on Cuba".[167]

On 28 October, Kennedy participated in telephone conversations with Eisenhower[168] and fellow former US President Harry Truman.[169] In these calls, Kennedy revealed that he thought the crisis would result in the two superpowers being "toe to toe"[168] in Berlin by the end of the following month and expressed concern that the Soviet setback in Cuba would "make things tougher"[169] there. He also informed his predecessors that he had rejected the public Soviet offer to withdraw from Cuba in exchange for the withdrawal of US missiles from Turkey.[168][169]

The US continued the blockade; in the following days, aerial reconnaissance proved that the Soviets were making progress in removing the missile systems. The 42 missiles and their support equipment were loaded onto eight Soviet ships. On 2 November 1962, Kennedy addressed the US via radio and television broadcasts regarding the dismantlement process of the Soviet R-12 missile bases located in the Caribbean region.[170] The ships left Cuba on November 5 to 9. The US made a final visual check as each of the ships passed the blockade line. Further diplomatic efforts were required to remove the Soviet Il-28 bombers, and they were loaded on three Soviet ships on 5 and 6 December. Concurrent with the Soviet commitment on the Il-28s, the US government announced the end of the blockade from 6:45 pm EST on 20 November 1962.[citation needed]

At the time when the Kennedy administration thought that the Cuban Missile Crisis was resolved, nuclear tactical rockets stayed in Cuba since they were not part of the Kennedy-Khrushchev understandings and the Americans did not know about them. The Soviets changed their minds, fearing possible future Cuban militant steps, and on 22 November 1962, Deputy Premier of the Soviet Union Anastas Mikoyan told Castro that the rockets with the nuclear warheads were being removed as well.[45]

The Cuban Missile Crisis was solved in part by a secret agreement between John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev. The Kennedy-Khrushchev Pact was known to only 9 US officials at the time of its creation in October 1963 and was first officially acknowledged at a conference in Moscow in January 1989 by Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin and Kennedy's speechwriter Theodore Sorensen.[171][172][173] In his negotiations with Dobrynin, Robert Kennedy informally proposed that the Jupiter missiles in Turkey would be removed[173] "within a short time after this crisis was over".[174] Under an operation code-named Operation Pot Pie,[175][153][154][155][156] the removal of the Jupiters from Italy and Turkey began on 1 April, and was completed by 24 April 1963. The initial plans were to recycle the missiles for use in other programs, but NASA and the USAF were not interested in retaining the missile hardware. The missile bodies were destroyed on site, while warheads, guidance packages, and launching equipment worth $14 million were returned to the United States.[176][177] The dismantling operations were named Pot Pie I for Italy and Pot Pie II for Turkey by the United States Air Force.[154][156]

The practical effect of the Kennedy-Khrushchev Pact was that the US would remove their rockets from Italy and Turkey[178][179] and that the Soviets had no intention of resorting to nuclear war if they were out-gunned by the US.[clarification needed][failed verification] Because the withdrawal of the Jupiter missiles from NATO bases in Italy and Turkey was not made public at the time,[173] Khrushchev appeared to have lost the conflict and become weakened. The perception was that Kennedy had won the contest between the superpowers and that Khrushchev had been humiliated. Both Kennedy and Khrushchev took every step to avoid full conflict despite pressures from their respective governments. Khrushchev held power for another two years.[166]: 102–105 As a direct result of the crisis, the United States and the Soviet Union set up a direct line of communication. The hotline between the Soviet Union and the United States was a way for the President and the Premier to have negotiations should a crisis like this ever happen again.[180]

Nuclear forces

editBy the time of the crisis in October 1962, the total number of nuclear weapons in the stockpiles of each country numbered approximately 26,400 for the United States and 3,300 for the Soviet Union. For the US, around 3,500 (with a combined yield of approximately 6,300 megatons) would have been used in attacking the Soviet Union. The Soviets had considerably less strategic firepower at their disposal: some 300–320 bombs and warheads, without submarine-based weapons in a position to threaten the US mainland and most of their intercontinental delivery systems based on bombers that would have difficulty penetrating North American air defence systems. However, they had already moved 158 warheads to Cuba; between 95 and 100 would have been ready for use if the US had invaded Cuba, most of which were short-ranged. The US had approximately 4,375 nuclear weapons deployed in Europe, most of which were tactical weapons such as nuclear artillery, with around 450 of them for ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and aircraft; the Soviets had more than 550 similar weapons in Europe.[181][182]

United States

edit- SAC

- ICBM: 182 (at peak alert); 121 Atlas D/E/F, 53 Titan 1, 8 Minuteman 1A

- Bombers: 1,595; 880 B-47, 639 B-52, 76 B-58 (1,479 bombers and 1,003 refuelling tankers available at peak alert)

- Atlantic Command

- 112 UGM-27 Polaris in seven SSBNs (16 each); five submarines with Polaris A1 and two with A2

- Pacific Command

- 4–8 Regulus cruise missiles

- 16 Mace cruise missiles

- Three aircraft carriers with some 40 bombs each

- Land-based aircraft with some 50 bombs

- European Command

- IRBM: 45 Jupiter (30 Italy, 15 Turkey)

- 48–90 Mace cruise missiles

- Two US Sixth Fleet aircraft carriers with some 40 bombs each

- Land-based aircraft with some 50 bombs

Soviet Union

edit- Strategic (for use against North America):

- ICBM: 42; four SS-6/R-7A at Plesetsk with two in reserve at Baikonur, 36 SS-7/R-16 with 26 in silos and ten on open launch pads

- Bombers: 160 (readiness unknown); 100 Tu-95 Bear, 60 3M Bison B

- Regional (mostly targeting Europe, and others targeting US bases in east Asia):

- MRBM: 528 SS-4/R-12, 492 at soft launch sites and 36 at hard launch sites (approximately six to eight R-12s were operational in Cuba, capable of striking the US mainland at any moment until the crisis was resolved)

- IRBM: 28 SS-5/R-14

- Unknown number of Tu-16 Badger, Tu-22 Blinder, and MiG-21 aircraft tasked with nuclear strike missions

United Kingdom

edit- Bomber Command[183]

- Bombers: 120; Vulcan B.1/B.1A/B.2, Victor B.1/B.1A/B2, Valiant B.1

- IRBM: 59 Thor (missiles operated by the RAF with warheads under US supervision)

Aftermath

editCuban leadership

editCuba perceived the outcome as a betrayal by the Soviets, as decisions on how to resolve the crisis had been made exclusively by Kennedy and Khrushchev. Castro was especially upset that certain issues of interest to Cuba, such as the status of the US Naval Base in Guantánamo, were not addressed. That caused Cuban–Soviet relations to deteriorate for years to come.[44]: 278

Historian Arthur Schlesinger believed that when the missiles were withdrawn, Castro was more angry with Khrushchev than with Kennedy because Khrushchev had not consulted Castro before deciding to remove them.[note 2] Although Castro was infuriated by Khrushchev, he planned on striking the US with the remaining missiles if an invasion of the island occurred.[44]: 311