- St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church (Manhattan)

- https://s3.amazonaws.com/NARAprodstorage/lz/electronic-records/rg-079/NPS_NY/80002719.pdf

- https://stbarts.org/connect/history-and-architecture/

- ("st. bart's" or "st. bartholomew's" or "saint bartholomew's") and ("park avenue" or "park ave" or "park av" or "manhattan") and "New York" NOT ("display ad" OR "classified ad" OR "advertisement" OR "arrival of buyers" OR "paid notice") NOT title("wed") not title("married") not title ("wedding")

St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House | |

New York City Landmark No. 0275

| |

(2012) | |

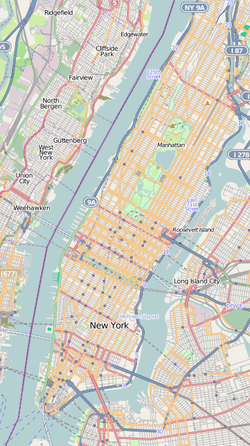

| Location | 109 E. 50th St. Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′26″N 73°58′25″W / 40.75722°N 73.97361°W |

| Area | 1 acre (0.40 ha) |

| Built | 1903 |

| Architect | Bertram Goodhue McKim, Mead & White |

| Architectural style | Romanesque Revival, Byzantine Revival |

| Website | stbarts.org |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002719[1] |

| NYSRHP No. | 06101.000091 |

| NYCL No. | 0275 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 16, 1980 |

| Designated NHL | October 31, 2016 |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 23, 1980[2] |

| Designated NYCL | March 16, 1967 |

St. Bartholomew's Church, commonly called St. Bart's, is a historic Episcopal parish founded in January 1835, and located on the east side of Park Avenue between 50th and 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan, in New York City. The church is known for a wide range of programs. It draws parishioners from all areas of New York City and surroundings. It is the final resting place for actresses Lillian Gish (1893–1993), Dorothy Gish (1898–1968), and their mother Mary Gish (1876–1948). The current church was erected in 1916–17.

The St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House complex was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2016.[3]

History

editEarly history

editFirst church

editThe congregation was organized in January 1835 and began constructing its first building, a plain structure at the corner of Great Jones Street and Lafayette Place, that June.[4][5] The first building was, at the time, located in what was one of the city's most fashionable areas.[6][7] In its first 100 years, the church had only seven rectors. The first rector, Charles Vernon Kelly, resigned in 1838 amid the Panic of 1837.[8] He was succeeded by Lewis P. W. Balch.[8][9] The third rector, Samuel Cooke, ascended to that position in the mid-1840s and served as rector for the next several decades.[9] Congregants in the first church included judge Samuel Jones and businessmen William B. Astor and William H. Vanderbilt.[9]

By the mid-19th century, the center of Manhattan's population had gravitated uptown.[9]

Second church

editThe second location was built at the southwest corner of Madison Avenue and East 44th Street.[10][11] It was designed by James Renwick, the architect of St. Patrick's Cathedral, in the Lombardic style.[5][12] William Kissam Vanderbilt's wife Alva Erskine Smith bought the second building's site,[13] paying the New York and Harlem Railroad $150,000 (equivalent to $4,735,862 in 2023).[5][14] The cornerstone of the second building was laid on October 2, 1871,[15] and the structure was largely developed from 1872 to 1876.[12][16] The church ultimately cost $228,584 (equivalent to $5,813,653 in 2023).[14] It was consecrated on February 21, 1878.[17] The new church's chancel was made of several types of marble, and there was a white altar atop the chancel.[18] Cooke served as rector until 1888[19] and was succeeded by David Hummel Greer, the church's fourth rector.[8]

Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was part of St. Bart's vestry, donated land in the 1890s for a parish house, which was built for $335,143.[14] When the second building was renovated in 1893, a reredos made of Caen stone, depicting the Last Supper, was installed behind the altar.[18] An electric organ was also installed, and the church reopened in October 1893.[20] These renovations cost $103,000.[14]

By June 1901, the church's parish house accommodated three clubs with a combined membership of over 2,500: the Girls' Club, Mens' Club, and Boys' Club.[21] The building was embellished in 1902–1903 with a triple French Romanesque Revival portal by Stanford White.[22] Leighton Parks subsequently became St. Bartholomew's fifth rector in 1904.[23] The church was further expended in 1909 at a cost of $90,000.[14]

Relocation to Park Avenue

editBy 1914, the second church had been surrounded by high-rise development, and the church building itself had deteriorated severely. The foundations had settled, causing the floor to sag; the roof had to be replaced; and the building was in danger of collapsing entirely.[24] Furthermore, maintenance costs had reached $253,000 per year.[25] At the time, theatrical figures and their children comprised many of the parishioners.[26] In April 1914, Parks notified his congregation that the vestry had agreed to acquire a new site for the church.[25][24] This site measured 200 feet (61 m) wide on Park Avenue, 250 feet (76 m) wide on 51st Street, and 225 feet (69 m) wide on 50th Street.[25][27] The land had been occupied by the Schaefer Brewery, one of Manhattan's largest breweries.[27][28] St. Bartholomew's officers voted on June 8, 1914, to exercise their option for the brewery site, although the church would not be able to move there for 18 months.[29] Two days later, the church took title to the site, having paid $1.5 million.[30][31] To fund the new building's construction, the vestry wished to sell the old Madison Avenue building for $1.4 million and resell the northern portion of the newly-acquired Park Avenue site for $500,000.[32]

Planning

editParks wanted to attract commuters from the newly-opened Grand Central Terminal, as well as tourists, so he wanted the new building to fit 1,500 people.[33] The rector and the vestry also wished to relocate Stanford White's portal to the second church, as the portal honored one of the church's most prominent congregants and had been completed a decade earlier.[25][34] The church created an art committee, headed by Alvin Krech, to select an architect for the building. Bertram Goodhue, who kew Krech through the Century Association, was hired in June 1914 to design the new building.[34] He did not want to design the edifice in the Gothic style, as it was too expensive, but the vestry's members were skeptical about Goodhue's original plans for a Romanesque edifice.[35] Goodhue ultimately modeled the building's plan after St Mark's Basilica, maximizing the number of pews in the crossing and transepts.[36] Since the vestry was unsure whether the northern part of the site would be sold, Goodhue prepared two sets of plans: one for a structure occupying the whole site and one for a structure occupying half the lot. Members of the vestry also objected to the materials that Goodhue had proposed to use, such as the stone and brick masonry on the facade and the tilework for the crossing.[37]

The original plans called for an almost square layout, with the nave being only slightly longer than the transepts.[38] The vestry rejected Goodhue's original drawings in January 1915, but it approved a modified plan later that month.[37] Goodhue told them the edifice could be built for $500,000, even though the architect himself believed that the building would cost $600,000 to $700,000.[39] Nonetheless, Parks appointed a building committee in March 1915 to oversee the building's financing. During this time, Goodhue and the church's art committee continued to disagree over what materials to use, even as Goodhue had begun hiring engineers and creating drawings for the site.[39] The vestry considered selling the northern portion of the site to the Racquet and Tennis Club, but, in June 1915, Goodhue decided to lengthen the nave to provide additional seating capacity. This necessitated relocating the proposed church to the northern part of the lot and increased the cost by $100,000.[40] The vestry ordered a scale model of the new building.[38]

Parishioners viewed a scale model of the building in January 1916.[38][41][42] The same month, St. Bartholomew's vestry modified the plans; instead of the building occupying the whole Park Avenue frontage, it would share the site with a 75-foot-wide (23 m) apartment house.[38][43] The vestry was still undecided about whether to use the whole site.[38] In February 1916, the church's building committee presented three proposals for the site.[44] Scheme A occupied the southern part of the site, scheme B occupied the northern part, and scheme C occupied the whole width of the block.[44] Even though scheme B was the most expensive of the three proposals (costing $1.2 million),[45] the vestry chose scheme B because it would provide 1,500 seats (including 225 in folding chairs), while scheme A only provided 1,300 seats.[44]

Construction

editParishioners began raising money for the new building in early 1916.[46][47] If the parishioners did not raise $1 million by that December, the project would be canceled;[48] Parks said he would resign if the congregation donated insufficient funds.[47] Around the same time, Parks accused Goodhue of inflating the project's construction cost to $684,700; this dispute created distrust between the vestry and Goodhue.[49] The vestry approved a modified plan for the new building in June 1916. It decided the following month to construct the building but not its chapel, as construction costs had risen significantly.[50] By the end of the year, the church had hired Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz to downsize the building to save money. Eidlitz eliminated the cloister and the tower above the building's crossing; replaced various materials with cheaper alternatives; and decreased the building's height by 4 feet (1.2 m).[51] By January 1917, the congregation had raised $1 million, prompting Bishop David H. Greer to announce that work on the new building would begin immediately.[52][53]

The vestry awarded numerous construction contracts and began laying the building's foundation in early 1917, although unexpected difficulties increased the foundation's cost by $11,000.[53] Greer and two hundred congregants laid the foundation stone on May 1, 1917,[54][55][56] at which point the building was projected to cost $3.5 million.[57] Greer predicted the third church would "last at least longer than former ones have done".[57] The building had been planned with a dome, but the dome's construction was deferred in 1917 due to high material and labor costs.[58][59] The building's steel frame was erected rapidly, and the roof had been installed by July 1917, but the decorations still had to be installed over the next year. Construction costs had reached $1.27 million by September 1917, and officials anticipated that they would spend another $1 million on the project.[60]

By January 1918, the vestry had decided not to construct the garden or install ornamental tiles. To further save money, contractors salvaged some materials from the Madison Avenue building, including the marble paving, stained-glass windows, chancel rail, choir stalls, a painting above the second building's altar, and a reredos.[61] The church's old building closed on May 20, 1918,[62] and Greer officially opened the new building on October 20, 1918.[63][61] After the third building on Park Avenue was completed, the New York Supreme Court approved the sale of the old building in July 1919.[64] At the time of the building's opening, the northern facade, acoustic tiles, marble revetment, and crossing remained incomplete; the crossing had a temporary roof. The garden was being landscaped by December 1918, and Parks solicited donations from his parishioners to fund the building's completion. Nonetheless, the church's treasurer reported in late 1919 that there was only $47,000 remaining in the building fund.[65]

Early 1920s and community house

editAlthough Goodhue urged the building committee to expand the structure in 1922, church officials could not expand the building until the church's debt had been paid off.[65] To raise money, the church sold off several of its old buildings, raising $1 million.[19] St. Bartholomew's vestry also announced in 1922 that it would acquire every pew that the church had sold to its parishioners. The church had sold many of its pews in the late 19th century, as it was common for parishioners to bequeath pews to their children; with fewer descendants attending the church, approximately 61 pews were being rented out by the 1920s.[66] The church had repurchased all pews by April 1923, and the vestry began renting out pews and selling memorial tablets to increase the church's $500,000 endowment.[67] By then, the church's debt had decreased to $155,000;[68] after the debt was paid off, Parks consecrated the church on May 1, 1923.[69][70] The next year, Parks announced that the church's loan association and benefit society, both of which had operated for nearly three decades, would stop operating because the vast majority of the church's 3,716 parishioners did not need these organization's services.[71]

The southern part of the church's site was still unoccupied, so Parks proposed constructing a parish house and rectory there.[72] Parks announced in March 1925 that he would resign as St. Bartholomew's rector,[73] and Robert W. Norwood was selected as the church's sixth rector shortly thereafter.[74] Norwood, a devout Protestant, frequently stated that he was "free for discussion of timely events"; many of his services incorporated text from the Bible, as well as mentions of current events.[75] Norwood had wanted to complete the church's dome, but parishioners convinced him to first build a community house.[76] Under Norwood's leadership, the plans for the parish house and rectory were changed to those for a community house and garden.[77]

The vestry was considering plans for the community house by January 1926. Goodhue had died the previous year, so the vestry hired his firm, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue Associates, that April to design a $575,000 community house.[67] Parishioners raised money for the construction of the community house, which replaced the church's parish house at 42nd Street and Third Avenue.[78] The sale of the old parish house netted $1.6 million, nearly all of which was used to furnish the community house.[77] Work on the community house began in June 1926, after the Cauldwell-Wingate Company was hired as the general contractor.[79] Bishop William T. Manning dedicated the community house on November 29, 1927.[79][80] Initially, only members were allowed to enter the community house, paying $1 a month. Members did not need to be Episcopalians, but membership was capped at 600.[77] The church established a community theatre, the St. Bart's Playhouse, in 1927 with funding from the Vanderbilt family.[81]

Dome and interior

editMeanwhile, Norwood wanted to furnish the church building's interior, which was largely bereft of decoration. There were bronze doors at the entrance to the chapel, and Lee Lawrie had carved a lectern and pulpit, but these had been donated to the church as private memorials.[82] Church officials asked Mayers and Murray of Goodhue Associates to draw new sketches for the interior in February 1927.[82] Krech, who still led the church's art committee, decided to decorate the interior of the apse with Byzantine-style mosaics, even though the style clashed with Goodhue's original Romanesque design. Goodhue Associates and artist Hildreth Meière created preliminary design for the interior in October 1927 and exhibited a model of the apse in May 1928.[82] Norwood sought to raise $700,000 in total, and parishioners had raised nearly $555,000 of this amount by April 1929.[83] Parishioners donated $123,637 during Easter 1929 alone; this amount was used to fund the construction of a marble revetment in Greer's honor.[82] The mosaics in the apse were completed in October 1929.[82]

Meanwhile, the art committee had started raising $350,000 for the dome in January 1929, and the church had raised sufficient funds for the dome by the end of that year.[84] Church officials announced in January 1930 that they would complete both the dome and the mosaic tiles in the narthex.[58][59] Mayers, Murray and Phillips filed plans for the dome in March 1930 at a cost of $350,000.[85] The work also included replacing the tile floor with marble; adding acoustic tile to the walls of the nave, transepts, and chancel; adding stone cladding to the crossing's arches; and replacing temporary doors just inside the lobby.[86] Church officials planned to install an organ in the dome,[87] supplementing existing organs in the chancel and rear.[87] Emily Vanderbilt White funded the installation of the organ, as well as the completion of the narthex.[84] The dome was completed in September 1930,[76] and the first service under the new dome was held on October 5, 1930.[88][89] The main building had to be rededicated because it had undergone so many alterations;[19][90] as such, Manning rededicated the building on December 9, 1930.[84][91][92] The entire edifice had cost $3 million to construct,[88][89] of which the dome had cost $750,000.[89][90]

Mid-20th century

edit1930s and 1940s

editAlthough St. Bartholomew's congregation remained largely upper-class, the church was also impacted by the Great Depression in the United States. By February 1932, the church was spending $1,000 per week on social-services programs, prompting the congregation to reduce the salaries of the church's staff members by 10 percent.[93][94] Norwood died in September 1932,[75] and George Paul Torrence Sargent was selected as the church's next rector that November;[95] he formally assumed that position in February 1933.[96][97] In spite of the Depression, the church had paid off its entire construction debt by December 20, 1932.[84] The congregation celebrated its centennial in January 1935;[98] during these celebrations, the parishioners dedicated a bust of Norwood.[99][100] The Emma J. Adams Memorial Fund funded a food pantry and homeless shelter at St. Bart's, one of the first such programs in a New York City church.[101]

Sargent announced in 1942 that the family of Adelaide Sheldon had donated 14 stained-glass windows to the church, while Emily Vanderbilt White donated a stained-glass rose window for the south transept;[102] Sheldon's family subsequently donated another eight windows.[103] The firm of Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock designed all of the stained-glass windows.[103][104] White's window was dedicated in November 1943,[105][106] while Sheldon's windows were dedicated in November of the following year.[103] In addition, after All Hallows-by-the-Tower in London was damaged in the Blitz, a stone from that church was rededicated next to St. Bart's pulpit in 1943.[107][108] A clerestory window was dedicated at the church in 1949.[109]

Sargent announced in January 1950 that he would resign as rector,[110][111] and Anson Phelps Stokes succeeded Sargent that November.[112][113] Two chancel screens, as well as a plaque honoring Sargent, were dedicated at the church in January 1954.[114][115] Stokes served as rector for only four years, resigning in November 1954 to become the bishop coadjutor of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.[116][117] He was succeeded by Terence J. Finlay,[118] who was officially installed as the church's rector in October 1955.[119] Following a donation from the William N. Cromwell Fund, an air-conditioning system was installed at St. Bart's, making it the completely air-conditioned Protestant church in New York City.[120] The air-conditioning system was completed in July 1956.[120][121]

1960s and 1970s

editBy the 1960s, many of the nearby apartment buildings on Park Avenue had been replaced with office buildings. St. Bartholomew's Church was one of the few remaining structures on the midtown section of Park Avenue that was not replaced with office development.[122][123] Even so, the church was negatively affected, as many of the parishioners who had lived in these apartment buildings relocated to the suburbs.[124] Parishioners planted two small gardens outside the church in 1964.[125] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House as a New York City landmark in 1967.[126]

Thomas D. Bowers, the rector of St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Atlanta, was selected as St. Bartholomew's rector in 1978.[127] Bowers implemented several changes. For example, he began using a prayer book mandated by the Episcopal General Convention; allowed laypeople to participate in liturgical readings; and ended the practice of charging parishioners a fee to use the pews.[124] The church's finances had steadily declined in the preceding years, and numerous affluent parishioners had left the congregation.[128] The church was still active in 1980, with approximately 2,000 parishioners, although it had lost more than a third of its congregants in the preceding three decades.[16] Although the public had long perceived St. Bartholomew's congregation as rich, an 1981 survey of the church's congregation found that about 75 percent of parishioners were single and that most parishioners were middle-class.[124] The church's $12 million endowment was no longer sufficient to fund its $2.6 million annual budget.[124][129]

Proposed demolition

editDuring the 1980s, St. Bartholomew's was the subject of a much-publicized dispute between historic preservationists and real-estate developers, which concerned the construction of a tower on the church's site.[130][131] Although the tower was ultimately not built, architect and writer Robert A. M. Stern said the dispute "engaged the public in crucial issues of aesthetics, real estate development, and constitutionality".[131] The dispute was the subject of Brent C. Brolin's 1988 book The Battle of St. Bart's.[132]

Original plan

editAn unidentified large company offered to buy the church's site for $100 million and erect an office tower there in September 1980.[133][134] An alternative plan would leave the main building intact,[133][134] but the unused air rights on the main building's site would be transferred to the new office building on the smaller site.[135] Bowers supported the tower's development, saying it would provide funding for the church.[136] The church's treasurer said income from the tower would both pay for renovations and fund the church's growing deficits, which were expected to increase from $323,000 in 1981 to $1.8 million in 1986.[137] The planned sale quickly became controversial both within the congregation and among the general public.[138] Opponents said the church could sustain itself on $300,000 in annual donations,[137] and church officials unanimously voted in October 1980 to reject the sale of the entire site.[139][140] The controversy affected the church's 1980 vestry elections, as the vestry had to approve the sale, and eight of the vestry's 15 seats were up for election.[135][a] Candidates endorsed by Bowers won about 70 percent of the votes.[129]

Several opponents of the sale established the Committee to Save St. Bartholomew's Inc. in December 1980.[141] Early the next year, a joint venture of Donald Trump and Peter Kalikow submitted plans for a glass tower designed by Eli Attia,[16] while the Cohen Brothers proposed a 26-story building by Richard Dattner.[16][142] Bowers and the vestry agreed in June 1981 to lease out the garden and community house,[143] The church also hired Princeton University School of Architecture dean Robert Geddes to study the feasibility of the various proposals.[16][143] That October, preservationists formed the Save St. Bartholomew's group to oppose the development.[144] At the end of that month, St. Bartholomew's vestry approved the plan.[145] The vestry also announced that British developer Howard P. Ronson would build a 59-story skyscraper on the site,[146] designed by Peter Capone of Edward Durell Stone's architectural firm.[147] The congregation voted on the lease proposal in November 1981, but opponents obtained an injunction from the New York Supreme Court,[148] and the church nullified these votes.[149] At a second referendum that December, the church's parishioners voted to approve the skyscraper by a 375–354 margin.[150]

The LPC and the New York City Planning Commission still needed to approve the tower, and the Episcopal Diocese of New York had to approve the lease.[151] The Appellate Division of the State Supreme Court placed an injunction on the sale in January 1982[152] and subsequently moved to reject opponents' appeal.[153] Paul Moore Jr., the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, approved the lease in February 1982,[154] and a state court approved the lease that May.[155] Opponents, led by J. Sinclair Armstrong, filed additional lawsuits that delayed the project for several months.[156] Ronson was supposed to place a $1 million down payment, but he had only paid $200,000 by the beginning of 1983.[156][157] The same year, the church unsuccessfully petitioned the New York State Legislature to pass legislation that would exempt religious institutions from statewide historic-preservation laws.[156][158]

LPC denial and modification

editThe church submitted their first plans to the LPC in December 1983.[156][159] As part of the project, the community house's interior would have been demolished, and a new community house would have been built on the lowest nine stories of the office building.[160] In a case pending before the New York Court of Appeals, the church argued that the city's landmarks law violated the First Amendment to the United States Constitution by infringing on its right to practice religion freely.[156][160] Following an acrimonious hearing at New York City Hall of Records in February 1984,[161] the LPC unanimously rejected the church's plans for the tower that June.[162]

The church presented modified plans for the site in December 1984.[163][164] In contrast to the original proposal for a 59-story glass tower, the revised plans called for a 47-story masonry-faced building with about half the floor area.[164] The second plan would have generated $3.5 million per year for the church, compared to $9.5 million per year for the first plan.[165] Half of the income from the tower would have been used to fund programs for the poor.[166] The congregation celebrated its 150th anniversary in January 1984,[167] and the LPC held a public hearing on the revised plans the same month.[168] If the second proposal were denied, church officials said they would claim financial hardship, which would allow them to modify the building.[168] The LPC unanimously rejected the second plan in July 1985.[169] Bowers said two months later that he would file an application of financial hardship with the LPC.[165]

At a public hearing for the church's hardship application in October 1985, church officials said the main building and community house needed $11 million worth of repairs.[170][171] According to church officials, the proposed tower would accommodate enlarged programs for children and the homeless.[170] A former church trustee claimed that the church had $6 million on hand for the restoration of the main building and community house, but he said church officials had claimed that only $500,000 was available.[172] Preservationists filed a lawsuit in the State Supreme Court, claiming that the vestry was mismanaging the church's funds by soliciting plans for the tower, but a judge ruled in favor of the vestry in December 1985.[173] The LPC rejected the church's hardship application in February 1986, saying that church officials had failed to prove that the existing facilities were deficient.[174]

Court challenges

editBowers, who alleged that the LPC's commissioners had been biased against the church from the outset,[175] sued the city government in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in April 1986.[176][177] The church could only proceed with its lawsuit if a majority of parishioners approved,[178] and nearly two-thirds of parishioners voted in support of the suit that September.[179] Manuela Hoelterhoff of The Wall Street Journal wrote the same year that the church was likely inflating the project's budget; for example, the church wanted to spend $350 per square foot ($3,800/m2) on a soup kitchen (which was reportedly at least twice as expensive as a gourmet restaurant's kitchen) and $800,000 on organ restoration.[180] The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported in 1988 that Bowers had an annual income of $100,000 and employed 70 staff members. At the time, the church operated a homeless shelter, an employment office, a health clinic, a day-care center, and Sunday school programs in several languages.[181] The St. Bart's Playhouse also continued to operate during this time.[81]

Opponents had sued the church in the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state, claiming that the vote on whether to support the church's lawsuit against the city was unfair; the Court of Appeals ruled in April 1987 that the development did not violate New York's religious corporations law.[176][182] Federal judge John E. Sprizzo ruled in July 1987 that the city's landmark law was constitutional, although he did not specifically rule on the LPC's refusal to approve the church's proposed tower.[183] Sprizzo further ruled in December 1989 that the church's landmark designation did not infringe on the church's First Amendment rights,[176][184] and the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld this ruling the next year.[176][185] In March 1991, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to consider the church's appeal of the city-landmark designation, effectively canceling the tower.[186][187]

Restoration efforts

edit1990s and early 2000s

editAt the time of the tower's cancellation, the church's endowment had dwindled to $9 million, and it had 600 regular donors, who could not raise enough money to fund the church's programs.[166] Furthermore, many parishioners who had opposed the tower had left the congregation during the 1980s.[166] St. Bartholomew's officials estimated that the church needed $10 million for its endowment and $20 million for repairs.[166] Church officials said that, if they could not raise funds for the building, the church would have to relocate.[186] As a conciliatory move to opponents of the tower's development, church officials asked the New York Landmarks Conservancy to examine the building,[130][188] and the church began hosting the annual meetings of the Municipal Art Society.[189] Moore took over as interim rector in December 1992 after Bowers announced his retirement the same month.[190][191] The New York Landmarks Conservancy began conducting a structural examination of the church in late 1993.[188]

William H. Tully became the church's new rector in November 1994.[192] By that year, only 300 parishioners attended a typical Sunday service; the church had a net annual deficit of $600,000, and its annual budget had increased to $3.5 million.[193] The church only had a $6 million endowment, and St. Bart's staff were so poorly behaved that, according to The New York Times, "the head usher had been fired for divisive behavior".[194] The front steps and garden attracted homeless people and drug addicts.[195] The church still operated its day-care center, soup kitchen, and 12-bed homeless shelter, as well as a fitness center and a young adults' club.[193] St. Bart's Players continued to perform within the church's community house.[196] At the time, St. Bartholomew's offered two Sunday services, hosted two choirs, and employed four full-time priests; the hotel company Marriott Corporation was responsible for the church's maintenance.[195]

Tully planned to save money by shuttering unprofitable programs,[197] and he hired a general manager for St. Bart's, who reduced costs further and began recruiting new parishioners.[195] In February 1995, Tully closed the fitness center, which had declined to 263 members,[197] as well as the church's thrift shop.[198] The Cafe St. Bart's opened in the community house the same year; the 350-seat cafe, which provided income for the church, became popular among tourists and office workers.[199][200] St. Bart's also received income from lectures and concerts, and it operated a gift shop and daycare center.[195] The church was also raising money for the restoration of the Cheatham Memorial Garden by the late 1990s.[201] Between 1995 and 2002, the church's annual pledges increased from about $400,000 to $2.75 million. By 2002, St. Bart's had five Sunday services, which attracted up to 600 parishioners; five choirs; and seven priests.[195] The church also hired Reform rabbi Leonard Schoolman to lead St. Bart's Center for Religious Inquiry.[202][203] Cafe St. Bart's, which originally operated only during the summer, began operating year-round in late 2003.[204]

Master plan

editMurphy Burnham & Buttrick Architects created a master plan for St. Bart's in 2004, which proposed $100 million worth of capital improvements. Tully began soliciting donations in October 2007 to fund the highest-priority improvements.[205] Within two months, parishioners had raised $15 million, while corporations had donated $2 million for the first phase of the project, which was expected to cost $30 million.[206] St. Bartholomew's received donations from companies that owned or occupied nearby buildings, such as the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, Rudin Management, Colgate-Palmolive, and Mutual of America.[205] Longtime parishioner Diane Posnak donated a movable platform and altar to St. Bart's in 2011.[207] Tully ultimately retired in 2012.[194]

In the early 2010s, the administration of mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed the Midtown East rezoning, which would allow St. Bartholomew's Church, St. Patrick's Cathedral, and the Central Synagogue to sell their air rights.[208] Previously, the three houses of worship had been unable to sell their air rights because there were no adjacent buildings to which their air rights could be sold.[209] After the National Historic Landmarks Committee of the National Park Service Advisory Board unanimously recommended that the St. Bartholomew's site be designated a National Historic Landmark,[210] the complex was designated as such in November 2016.[211][212] Restoration of the church's dome was completed in 2017,[213] and Dean Elliott Wolfe was inducted as the church's rector the same year.[214] In October 2018, the church sold its air rights to JPMorgan Chase for the construction of the nearby 270 Park Avenue tower.[215]

St. Bart's began renting out its swimming pool and basketball courts on an hourly basis in mid-2023,[216] and the church announced that it would close its preschool at the end of the 2023–2024 academic year due to high costs.[217] In early 2024, St. Bart's sold 250,000 square feet (23,000 m2) of air rights to a group led by Citadel LLC for $78 million.[218][219]

Architecture

editThe church building was designed by Bertram Goodhue in the Byzantine Revival style.[201][220] The building was initially described as being in the Romanesque style, although this was likely done to placate the Vanderbilt family, who were part of St. Bart's congregation and preferred a Romanesque design. After the Vanderbilts left the congregation in 1923, sources almost invariably described the church building as being designed in the Byzantine style.[220] The interior, which was not completed until after the Vanderbilts left the church, was also completed in a Byzantine style.[221] Many of the current building's decorative features were salvaged from the second building on Madison Avenue, including the main entrance portico on the western elevation of the facade, as well as almost all of the furnishings that were added to the second church during the 1890s.[222] According to writer Christine Smith, the furnishings from the second church are all placed in "positions of secondary importance".[223]

The church is attached to a community house, which was designed in the same style by Goodhue's firm in the 1920s. The two structures wrap around a garden in an "L"-shape.[201] The northern portion of the church's site also includes the Sallie Franklin Cheatham Memorial Garden, which William Hamby designed in 1968[224] or 1971.[16] It consists of two fountains and a series of carved channels through which water flows.[224] The rest of the block is occupied by the General Electric Building to the northeast, designed by Cross & Cross,[201] and another office building to the southeast, designed by the Eggers Group.[225] The facades of both structures were designed in a similar color scheme as the church complex.[201]

When the current church building was announced in 1916, Royal Cortissoz wrote: "This church is so good as it stands that we hope it may be built along certain lines promising to give it even greater significance."[226] Ada Louise Huxtable wrote: "With all the exterior elements meticulously matched in scale and style, the complex is meant to look like one building, and it does."[201] A reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote that the main building "is something of a hodgepodge - a blocky, domed structure of salmon-colored stone with a mixture of Byzantine and Romanesque stylistic elements, and Gothic touches in the fenestration", while the community house was in a "restrained, and more profane, version of the same style". Christine Smith called the church complex "a jewel in a monumental setting" in 1988.[227]

Main structure

editGoodhue's original design called for a vast, unified barrel-vaulted[b] space, without side aisles or chapels and with severely reduced transepts.[10] As designed, the church has a cruciform arrangement.[228][229] The church is aligned on a west–east axis relative to Manhattan's street grid. The narthex at the western end of the church, facing Park Avenue, is 75 feet (23 m) wide; the nave is about half as wide as the narthex and is topped by a gable roof.[230] The transepts extend north and south from a crossing at the eastern end of the nave.[229] The north transept extends above a mortuary chapel. The south transept incorporates a chapel at its base and was originally intended to lead to a never-built cloister.[231] As built, the southern section of the nave is connected to a small chapel, and the south transept leads to the community house.[228]

Goodhue had designed the church with a facade of marble and brick.[41][42] The church's brickwork was primarily of two colors, salmon and "warm gray", which was intended as an allusion to Italian churches.[41] The Piccirilli Brothers created cast-stone decorations, both for the facade and for the interior, in various Italian architectural styles. The decorations included figures on the west elevation and south transept,[223] such as depictions of gargoyles,[232] as well as sculptures of saints on the south transept.[223] The church also contains Italian Romanesque-style capitals, and the north transept featured Byzantine and Romanesque-inspired plaques.[233] Goodhue's original plans did not include stained-glass windows, but they were added after the church building was completed.[104]

Facade

editThe primary elevation of the church building faces west toward Park Avenue.[228] The Park Avenue elevation contains a portico with three entrances (each with a pair of bronze doors), as well as Cipollino marble columns and green-marble paneling.[4][228] The portico had been designed for the second church[41][42] and funded by the Vanderbilt family as a memorial to Cornelius Vanderbilt II.[12] It was inspired by the church of Saint-Gilles, Gard, in France.[234] Daniel Chester French designed the portals themselves; Herbert Adams was responsible for the northernmost doors; French's assistant Andrew O'Connor executed the main door; and Philip Martiny designed the southernmost doors.[126][235] Each door contains a panel with representations of events in the saints' lives.[235] The portico contains twelve blue-green columns, which were intended to contrast visually with the original green hue of each bronze door. The central portal is flanked by two friezes, depicting scenes from the Old Testament and New Testament, each of which measure 12 feet (3.7 m) long.[235]

Above this portal, the central doorway on Park Avenue is topped by an enormous round-arched window.[228] The round arch is filled with a stained-glass window salvaged from the second church building.[223][236] The window contains tracery that may have been inspired by Celtic, Islamic, and Italian Romanesque sources.[237] The western elevation also contains a heavy tympanum with vertical lancets beneath it.[238]

On the northern and southern elevations, three arched windows illuminate the aisles of the nave, which extends from the western end of the church to the crossing.[228] The south transept is illuminated by an ornate rose window, which may have been inspired by that of St Mark's Basilica.[238] The rose window originally contained tinted glass, which was replaced in the 1940s with stained glass designed by Reynolds, Francis & Rohnstock.[104] John Gordon Guthrie designed additional stained-glass windows on both transepts, and six windows in the northern aisle, which were installed in 1929.[104] Hildreth Meière designed four more stained-glass windows for the upper section of the nave.[239][240] Meière's windows, as well as two additional stained-glass windows, were added in the 1960s.[240]

Mayers, Murray and Philips also inserted the "much discussed"[10] dome, which substituted for an unbuilt spire.[228][241][242][c] The crossing contained a square base for the spire, which would have been twice as high as the rest of the church, with more ornate decoration.[243] When the church's vestry rejected the spire, Goodhue's firm decided to design an octagonal dome, inspired by the dome of the California State Building at the Panama–California Exposition.[241] The dome, rising 140 feet (43 m) above the crossing,[228] is octagonal in plan and is supported by a large drum. It contains eight stone ribs that cut through its surface.[89][228] The exterior of the dome is made of stone and brick and contains mosaic tile patterning.[89][228] As planned, the dome was to measure 50 feet (15 m) across and contain stained-glass windows.[58][59]

Interior

editOriginally, the church building was intended to accommodate 1,488 people,[54] although later sources cite the church as having a capacity of 1,250[228] or 1,300.[228] The structural framework consists of concrete beams with stone and marble cladding.[228] Due to financial shortfalls at the time of the church building's completion, many of the decorative features were not completed for several years, and elements of the Gothic style were incorporated into the interior design later on.[244] The narthex contains an Art Deco-style artwork by Hildreth Meière, The Six Days of Creation.[239][245] The artwork consists of five domes with gold mosaic tiles.[239][236] The west organ loft is made of wood,[238] while the narthex has light marble cladding.[236]

Meiere designed the underside of the church's dome.[239][246] The ceiling of the crossing, directly under the dome, is made of Guastavino tile and decorated with wooden beams.[236][247] Goodhue originally intended to design the dome in the Romanesque style.[246] The dome's interior, which was only completed after Goodhue's death, is designed in a Hispano-Moresque style.[10][247] Cornelius Vanderbilt had donated a mural by Francis Lathrop,[55] which had been placed behind the second church's altar but was relocated to the current building's north transept.[222] Since 2011, St. Bart's has contained a four-piece movable platform and altar, which is made of wood and medallions that were reused from the church's old pews. The platform and altar is divided into four pieces, which are normally stored at the transept's corners but can be assembled when necessary.[207]

The choir and the apse's lower section are clad with light-colored marble,[228] while the rest of the apse is decorated with mosaic tiles, glass, and marble.[236] Goodhue had originally planned to cover the apse in marble, divided by ornamental-tile bands, although the vestry decided not to install these decorations to save money.[221] The apse's marble revetment was added in 1929 and consists of vertically-arranged marble panels with mosaic-tile frames.[248] There is also a mosaic artwork in the apse, which depicts the Transfiguration of Jesus.[249] The current church also contains a large marble baptismal font from the church's second building.[222] There is an altar rail and a communion rail, both made of colored marble and mosaic tiles; pieces of these rails may have come from the second building.[250]

The chancel contains Cosmati marble pavement,[251] as well as mosaic tiles and choir stalls from the second building.[222] There are also two chancel screens, which were dedicated in 1954; they represent the tree of life and measure 18 feet (5.5 m) wide by 25 feet (7.6 m) long.[114] The church's pulpit was completed in 1925 to designs by Lee Lawrie and is placed along the apse's wall. The pulpit is supported by a set of colonnettes, and its railing contains depictions of various figures.[252]

Community house

editMayers, Murray and Philips were engaged in erecting the five-story community house in the Byzantine style.[77][80] The exterior of the community house is constructed of brick and stone, the same materials used for the main building.[82] The church's rector at the time, Robert W. Norwood, said that he wanted "to begin with an auditorium, and build the rest of the Community House around it".[196]

The community building contained an auditorium, a gymnasium, dining rooms, and a swimming pool.[16][236] The ground-level swimming pool measured 90 by 40 feet (27 by 12 m) across and ranged in depth from 4 to 9 feet (1.2 to 2.7 m). There was also a ground-level gymnasium measuring 65 by 45 feet (20 by 14 m) across and 23 feet (7.0 m) high; it was used for indoor basketball and tennis. The first floor had an auditorium with a small stage, while the second floor had staff offices and a non-circulating library. The women's floor occupied the third story and had parlors, as well as lounges with folding tables. The fourth story contained a men's floor with pool rooms, billiard rooms, parlors, and lounges; there was also a grill room for luncheons. The children's floor was on the fifth story and contained a kindergarten, Boy Scouts clubroom, and girls' organizations.[77] Most of the community building's interior decorations were intact in the 1980s.[236]

Organs

editSt. Bartholomew's is noted for its Skinner Organ Company pipe organ, the largest in New York and one of the ten largest in the world. It was dedicated in a concert December 9, 1930, in a concert given by choirmaster David McKinley Williams.[253]

Organists

editOne of the church's former choir-directors was the famous conductor Leopold Stokowski, who was brought from the United Kingdom by St. Bart's; he was followed by the organist-choirmaster David McKinley Williams.

Another of the church's music directors was Harold Friedell, the well-known composer and Juilliard educator.

Programs

editThe church's renowned choir has maintained its distinction under the direction of conductors such as organist-music director Jack Ossewaarde, William Trafka and James Litton. The Chorister Program has also had success in bringing together children ages 6–18 to sing in the church, and has been featured on shows such as The Today Show and Good Morning America.

In 2020, it reported 2,196 members, average attendance of 386, and $2,791,353 in plate and pledge income.

Notable parishioners

editThe church has hosted memorial services for parishioners such as former U.S. first lady Lou Henry Hoover in 1944,[254] politician Newbold Morris in 1966,[255] publisher Malcolm Forbes in 1990,[256] and actress Lillian Gish in 1993.[257]

Gallery

edit-

View from the north on Park Avenue

-

First stained glass window from the entrance on the north side of the church.

-

Stained glass rose window over balcony overlooking the pews.

-

Facing west, silhouette of the organ against stained glass panels in balcony.

-

The altar.

-

Angel praying towards relief of the Last Supper in the baptismal chamber north of the altar.

-

Gallery Organ

-

North Chancel Organ

-

South Chancel Organ

-

Celestial Organ

See also

edit- Anglican Communion

- Anglo-Catholicism

- Churches Uniting in Christ

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- Complete List of Presiding Bishops

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- Succession of Bishops of the Episcopal Church in the United States

References

editNotes

- ^ Eight of the vestry's 15 seats were up for election in 1980. Five of the vestry's members are elected every year, and three members had met the vestry's mandatory retirement age.[135]

- ^ The church makes much use of Guastavino tile for its vaulting.

- ^ In Goodhue's former studio at 2 West 47th Street, Christopher Gray noted the discovery of "a photograph of the office's reception room containing a huge model of St. Bartholomew's with a giant spire that was never built."[242]

Citations

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ "Secretary Jewell, Director Jarvis Announce 10 New National Historic Landmarks Illustrating America's Diverse History, Culture". Department of the Interior. November 2, 2016. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ^ a b Rider 1923, p. 294.

- ^ a b c "St. Bartholomew's Moves Further Uptown". The New York Times. October 20, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Morrone, Francis (2009). Architectural Guidebook to New York City. Gibbs Smith, Publisher. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-4236-1116-5. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Goldstone, Harmon Hendricks; Dalrymple, Martha (1976). History Preserved: A Guide to New York City Landmarks and Historic Districts. Schocken books. Schocken Books. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8052-0544-2. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c "St. Bartholomew's Marks 100th Year; Park Avenue Church Arranges Centennial Program -- Its Rise Shown in Records". The New York Times. January 6, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Church-debts.: How a New York Rector Cleared Off a Debt of $145,000a in Two Months". Chicago Daily Tribune. December 23, 1877. p. 7. ProQuest 171851418.

- ^ a b c d Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. p. 236f. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.)

- ^ Gray, Christopher (October 8, 2006). "Time and Gravity Take a Toll on St. Bartholomew's Church". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c Dunlap, David W. (2004). From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan's Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12543-7.

- ^ "Last Service Held in Old Church of St. Bartholomew". New-York Tribune. April 29, 1918. p. 9. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 1988, p. 25.

- ^ "Laying the Corner-stone of St. Bartholomew's Church". New-York Tribune. October 3, 1871. p. 8. ProQuest 572527342.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 507.

- ^ "Consecrating a Church; Bishop Potter's First Consecration Service Performed in St. Bartholomew's Yesterday". The New York Times. February 22, 1878. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Old Gives Place to New; St. Bartholomew's Church Interior Handsomely Redecorated". The New York Times. October 1, 1893. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Bishop to Open New Church of St.Bartholomew: Dr. Manning Will Officiate Tuesday in Dedication of Edifice Used Since 1918 Structure Begun in 1916 Park Avenue Location Third Occupied in 95 Years Prepares for Dedication". New York Herald Tribune. December 7, 1930. p. A11. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113775454.

- ^ "Many Costly Improvements; Ninety Thousand Dollars Spent in Redecorating St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. October 23, 1893. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "Club Life Tn the Church: What Its Introduction Into Religious Work is Doing at St. Bartholomew's". New-York Tribune. June 23, 1901. p. A3. ProQuest 570952441.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's History." Archived April 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine From the church Web site. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ "Dr. Leighton Parks Dead in London, 86; Former New Yorker, Rector of St. Bartholomew's 21 Years and Militant Modernist". The New York Times. March 22, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d "St. Bartholomew's Buys Brewery Site; New Church Will Be Built at Park Avenue and Fiftieth Street". The New York Times. April 20, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "Church Appeals for $2,000,000: Dr. Parks Asks for Fund on Tenth Yeas as Rector at St. Bartholomew's Must Stay on Island, is Plea Foresees Thinning of Population in a Few Years--ascension Memorial Asks $50,000". New-York Tribune. February 2, 1914. p. 7. ProQuest 575216264.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 50.

- ^ Rider 1923, pp. 293–294.

- ^ "The Real Estate Field; St. Bartholomew's Church Votes to Take Up Option on $1,500,000 Park Avenue Site -- Investor Buys Bronx Corner -- Business and Dwelling Leases -- Bay Ridge Auction Results". The New York Times. June 9, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "Church Pays High for Brewery Site: St. Bartholomew's Buys Schaefer Land for $1,500,000--lots Once $1,000 Average $79,000". New-York Tribune. June 11, 1914. p. 3. ProQuest 575288414.

- ^ "The Real Estate Field; St. Bartholomew's Church Votes to Take Up Option on $1,500,000 Park Avenue Site -- Investor Buys Bronx Corner -- Business and Dwelling Leases -- Bay Ridge Auction Results". The New York Times. June 9, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 51.

- ^ Smith 1988, p. 52.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 1988, p. 56.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 55.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c d "$3,000,000 Church for Park Avenue: New St. Bartholomew's to Be Begun Soon on Plot at 50th Street". New-York Tribune. January 17, 1916. p. 9. ProQuest 575507720.

- ^ a b c "St. Bartholomew's New Plans Ready; Parish Plant Is to Replace the Brewery at Fiftieth Street and Park Avenue". The New York Times. January 17, 1916. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Changes Its Plans; Apartment House Will Share Park Avenue Block Front with New Church". The New York Times. January 18, 1916. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c Smith 1988, p. 57.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 58–59.

- ^ "Dr. Greer Urges $3,000,000 Church: Begs St. Bartholomew's to Build "Noble Civic Feature of Nation." Congregation Hears Stirring Appeals Members Favor $1,126,000 Outlay, Which Will Make New Edifice Possible". New-York Tribune. February 28, 1916. p. 6. ProQuest 575515770.

- ^ a b "Dr. Parks to Resign if Made 'Solicitor'; Tells St. Bartholomew's the Congregation Itself Must Raise Building Funds". The New York Times. February 28, 1916. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ Smith 1988, p. 59.

- ^ Smith 1988, p. 60.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 61–62.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Raises Its $1,000,000: Dr. Parks Announces That the Fund Asked for 10 Months Ago is All Pledged". The New York Times. January 8, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 62.

- ^ a b "Bishop Lays Cornerstone; Work on St. Bartholomew's New $3,000,000 Home Formally Begun". The New York Times. May 2, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "St. Bartholomew's Cornerstone is Laid". New-York Tribune. May 2, 1916. p. 7. ProQuest 575726767.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b "St. Bartholomew's Cornerstone Laid". The Sun. May 2, 1917. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c "To Complete Church Dome; St. Bartholomew's Gets $700,000 to Finish Park Av. Building". The New York Times. January 27, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c "St. Bartholomew Church To Build $700,000 Dome: Park Avenue Memorial Cupola Will House Organ in Roof". New York Herald Tribune. January 27, 1930. p. 15. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113086550.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 65.

- ^ "Last Service in St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. May 20, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Opened; Bishop Greer Preaches Sermon as Part of Patriotic Exercises". The New York Times. October 21, 1918. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "To Sell St. Bartholomew's; Court Permits Deal Disposing of Church Site for $1,425,000". The New York Times. July 25, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 66.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Wants Pews Back; Dr. Parks Says Some Owners Have Not Been in Them for 20 Years--Others Rent at Profit". The New York Times. February 22, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, p. 67.

- ^ "Church to be Consecrated". The New York Times. April 16, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Smith 1988, pp. 66–67.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Church Consecrated; Suffragan Bishop Shipman Officiates and Bishop Lawrence Speaks". The New York Times. May 2, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Has No Needy Now; Park Avenue Church Discontinues Its Benevolent Society and Its Loan Association". The New York Times. July 29, 1924. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2023. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ Smith 1988, p. 67.

- ^ "Dr. Parks Considers Quitting as Rector; He Has Served at St. Bartholomew's Church for Twenty-one Years". The New York Times. March 8, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ name=nyt-1925-03-19>"St. Bartholomew's Calls Dr. Norwood; Rector of St. Paul's, Overbrook, Philadelphia, to Succeed the Rev. Dr. Parks". The New York Times. March 19, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ a b "Dr. Norwood, Episcopalian Liberal Dies: St. Bartholomew's Rector, 57, Suffers Cerebral Hemorrhage as Vacation Ends Had Been Ailing 8 Years Often Opposed Bishop Manning; Known as Poet Rector of St. Bartholomew's". New York Herald Tribune. September 30, 1932. p. 9. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1221304088.

- ^ a b "Dome of Church Started in 1916 Now Completed: St. Bartholomew's to Hold First Official Service in Finished Edifice on Oct. 5 Built at $3,000,000 Cost High Price of Construction During War Delayed Work". New York Herald Tribune. September 27, 1930. p. 36. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113780146.

- ^ a b c d e "Bishop to Dedicate New Church House; St. Bartholomew's Community Centre Will Be Opened by Manning on Tuesday". The New York Times. November 27, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Episcopal Centre Ready; St. Bartholomew's Community House Begins Activities Nov. 1". The New York Times. October 23, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Smith 1988, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b "Bishop Manning Dedicates New Community House: Byzantine Structure of St. Bartholomew's Church Cost Almost $1,600,000". New York Herald Tribune. November 30, 1927. p. 22. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1132021872.

- ^ a b "Timeless Broadway survives on Park Ave". Daily News. May 7, 1989. p. 320. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Smith 1988, p. 68.

- ^ "Gifts to Build St. Bartholomew's Now $554,814 De.Norwood Pleads for 100,000 Subscribers". The New York Times. April 8, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Smith 1988, p. 69.

- ^ "Complete St. Bartholomew's Dome". The New York Times. March 15, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "12-Story Church And Apartments For E. 50th St: First Reformed Episcopal Congregations Plans to Begin Work on Structure Soon Tapestries for Cathedrel 700.000 Additions Will Be Made to St. Bartholomew's". New York Herald Tribune. May 31, 1930. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113704369.

- ^ a b "St. Bartholomew's to Have Dome-organ; Cupola Serving as Chamber for 1,825-Pipe Instrument to Be Ready by Oct. 1". The New York Times. May 6, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "Dome Opened By Dr. Norwood On Park Avenue: PastorSees 'Perpetual Hymn' in St.Bartholomew's, Completed After Sixteen Years Communion Is Celebrated Evening Worship Added as Fall Schedule Is Resumed". New York Herald Tribune. October 6, 1930. p. 12. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113202123.

- ^ a b c d e "Dr. Norwood Scores Intolerant Views; Fifth Anniversary Sermon Is First in Completed Edifice of St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. October 6, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ a b "St. Bartholomew's to Be Rededicated; Bishop Manning Will Preach and Officiate at Services to Be Held on Tuesday". The New York Times. December 7, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "Manning Dedicates St. Bartholomew's; Appears at Ceremony After Canceding Engagement, but LeavesAfter Prayers". The New York Times. December 10, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "New St. Bartholomew's To Be Dedicated Today: The Rt. Rev. C. K. Gilbert to Speak at Park Ave. Ceremonial Church To Be Dedicated Today". New York Herald Tribune. December 9, 1930. p. 23. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113711457.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Cuts Staff Pay 10%; Wealthy Church Reduces Its Salaries to Avoid Cutting Down Charity Work". The New York Times. February 29, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Church. Cuts All Salaries 10 P. C.: Park Ave. Congregation's Action Afifecls Staff of 150". New York Herald Tribune. February 29, 1932. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1221267519.

- ^ "Dr. Sargent Named as Park Av. Rector; Dean of Garden City Cathedral to Succeed Dr. Norwood at St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. November 30, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ "Install Dr. Sargent as Park Av. Rector; Four Bishops Take Part in the Ceremony Seen by 2,000 in St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. February 20, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "Bishop Installs Dr. Sargent as Park Av. Rector: Manning Institutes Former Dean at Garden City in St. Bartholomew Church". New York Herald Tribune. February 20, 1933. p. 8. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1240033734.

- ^ "Church Raises $505000 Fund For Centennial: St. Bartholomew's Donors Are Kept Anonymous; Woman Gives $25,000 Gift Service Tomorrow They Will Be Received at Altar in Closing Ceremony A Pageant Aids St. Bartholomew's to Mark Its Centennial". New York Herald Tribune. January 19, 1935. p. 12. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1243905300.

- ^ "BUST OF DR. NORWOOD UNVEILED AT CHURCH; 200 at Ceremony to Dedicate Memorial to Late Rector of St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. January 18, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ "250 at St. Bartholomew's Dedicate Norwood Bust: Tribute to Noted Modernist Part of Centennial Honoring a Former Rector of St. Bartholomew's". New York Herald Tribune. January 18, 1935. p. 14. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1328965613.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (January 20, 1987). "Metropolitan Desk". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Windows Given to Church; Gifts of Fifteen Are Announced by St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. December 7, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Chapel Altar Cross and 22 Windows Dedicated in St. Bartholomew's Church". The New York Times. November 20, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Smith 1988, p. 150.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Dedicates Lila Vanderbilt Field Window". New York Herald Tribune. November 8, 1943. p. 14A. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1282801880.

- ^ McDowell, Rachel K. (November 6, 1943). "Armistice Sunday' Marked Tomorrow: 'World Order Sunday' Also to Be Observed at Services in City's Churches". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Church Gets Historic Stone". The New York Times. September 26, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Historic Stone From London Enshrined Here: Wall Fragment of Bombed All Hallows Church Is Put in St. Bartholomew's". New York Herald Tribune. September 27, 1943. p. 12. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1267951838.

- ^ "New Church Memorial Dedicated". The New York Times. December 5, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's to Lose Its Rector; Dr. Sargent Will Quit on Nov. 1 After 17 Years' Service--He Will Get Emeritus Post". The New York Times. January 23, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Dr. Sargent, 68, Plans to Retire; Rector 17 Years: St. Bartholomew's Vestry Accedes, Votes to Make Him Rector Emeritus". New York Herald Tribune. January 23, 1950. p. 5. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1326834894.

- ^ "Dr. Sargent Ends Duties as Rector; Administers Holy Communion to Elderly Parishioners at St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. November 2, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "The Rev. Anson Phelps Stokes Jr. Is Installed at St. Bartholomew's". New York Herald Tribune. November 13, 1950. p. 19. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1327465136.

- ^ a b "2 Chancel Screens Dedicated at St. Bartholomew's". The New York Times. January 11, 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Dedicates 2 Myron C. Taylor Screens". New York Herald Tribune. January 11, 1954. p. 7. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322525925.

- ^ "Stokes Preaches Farewell to City; St. Bartholomew's Rector Will Become Bishop Coadjutor of Massachusetts on Dec. 4". The New York Times. November 22, 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Dr. Stokes in Last Sermon As St. Bartholomew's Rector". New York Herald Tribune. November 22, 1954. p. 22. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1322562089.

- ^ "Ottawa Rector is Called to City; The Rev. T. J. Finlay to Head St. Bartholomew's Staff Beginning in October". The New York Times. June 6, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Ninth Rector Is Installed At St. Bartholomew's Rite". New York Herald Tribune. October 10, 1955. p. 6. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1327591529.

- ^ a b "Cooling is Spread to Whole Church; Canadian Bishop Preaches in St. Bartholomew's, Now Fully Air-Conditioned". The New York Times. July 9, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "To Preach At St. Bartholomew's". New York Herald Tribune. July 7, 1956. p. A10. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1337733057.

- ^ Fowler, Glenn (February 27, 1966). "Park Ave. Lures Tenant-Owners; Banks and Businesses Are Replacing Real Estate Men". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ "Park Ave. Area Losing Suites". New York Herald Tribune. January 15, 1961. p. 1C. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1325233799.

- ^ a b c d Briggs, Kenneth A. (February 23, 1981). "St. Bartholomew's Split Goes Beyond Real Estate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 4, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Planting on Park Avenue". The New York Times. December 6, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 17, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- ^ a b New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

- ^ "St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church Selects Atlanta Rector for Post". The New York Times. April 30, 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Clendinen, Dudley (September 22, 1980). "The Faithful Have Doubts About a Bid for St. Bartholomew's Church; A Reaction From Near the Altar Church's Options Cited". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Hughey, Ann (January 20, 1981). "Church to the Wealthy, St. Bartholomew's Seethes Over Its Rector's Financial Plan". Wall Street Journal. p. 33. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 134666873.

- ^ a b Lambert, Bruce (January 22, 1995). "Neighborhood Report: Upper East Side; Ex-Foe Helps St. Bart's With Its Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 506.

- ^ Yardley, Jonathan (May 25, 1988). "Separating Church & Real Estate". The Washington Post. p. C02. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 306994831.

- ^ a b Horsley, Carter B. (September 19, 1980). "$100 Million Offered for Park Ave. Church; Unidentified Concern Seeks to Buy St. Bartholomew's Property Church Is a City Landmark St. Bartholomew's Gets an Offer Of $100 Million for Park Ave. Site Bishop Moore Is Informed 2,000 in Congregation Proposition is Still Open $2,000 a Square Foot Offered". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Stern, Richard; Kerber, Fred (September 20, 1980). "Offer for St. Bart's heavenly for values". Daily News. p. 328. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Horsley, Carter B. (December 14, 1980). "St. Bartholomew's Vote a Key to Church Land Sale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Oreskes, Michael (November 10, 1981). "Vision of St. Bart's Rector Pushes Tower Deal Ahead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Allen, Joy (December 22, 1981). "The Battle of St. Bartholomew's: All the classic elements are there-- wealth and poverty, church and state". Newsday. p. B3. ProQuest 993196312.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (October 10, 1980). "St. Bartholomew's Debates Church Sale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (October 15, 1980). "St. Bartholomew's Officials Refuse To Sell Their Church for Any Price; St. Bartholomew's Refuses to Sell Church Building Commission's Powers 'Outreach Programs'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Jasinski, Robert (October 15, 1980). "St. Bart's officials won't sell". Daily News. p. 115. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (December 21, 1980). "Injunction Sought in Dispute at St. Bartholomew's; 'Actual Confusion and Deception' Vestry Expresses Concern". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 19, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (May 3, 1981). "26-Story Office Tower Proposed for St. Bartholomew's Property". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Paul L. (June 4, 1981). "St. Bartholomew's to Proceed on Lease". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "Panel Seeks to Bar a Lease of St. Bart's Land". The New York Times. October 4, 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Oreskes, Michael (October 29, 1981). "Vestry Backs Skyscraper at St. Bartholomew". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ "New York Church Gives Design for Office Tower". Wall Street Journal. October 30, 1981. p. 37. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 134558754.

Oreskes, Michael (October 30, 1981). "Cost of Tower Near St. Bart's Will Be Higher by $33 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023. - ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 508–509.

- ^ Shipp, E. R. (November 17, 1981). "State Court Prohibits Meeting at St. Bart's on Its Lease Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Oreskes, Michael (November 18, 1981). "St. Bart's Bows to the Court; Vote on Lease Plan is Scrapped". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Fowler, Glenn (December 19, 1981). "Parish Approves Skyscraper Plan in St. Bart's Vote". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

Allen, Joy (December 19, 1981). "Landmark Church OKs Tower Lease". Newsday. p. 10. ProQuest 965002914. - ^ Montgomery, Paul L. (December 21, 1981). "At St. Bartholomew's, a Time to Heal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

Woodward, Eloise; Salholz (December 28, 1981). "The Battle of St. Bart's". Newsweek. Vol. 98, no. 26. p. 60. ProQuest 1866709036. - ^ "The City; Sale at St. Bart's Held Up by Court". The New York Times. January 8, 1982. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Allen, Joy (March 12, 1982). "St. Bartholomew's Wins Appeal on Vote on Tower". Newsday. p. 18. ProQuest 993585033.

- ^ Carmody, Deirdre (February 14, 1982). "Bishop Backs Plan to Lease St. Bart's Land to Developer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

"Bishop Approves Construction Near Bartholomew's". The Hartford Courant. February 15, 1982. p. A7. ProQuest 546601498. - ^ Haberman, Clyde; Johnston, Laurie (July 26, 1982). "New York Day by Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 510.

- ^ Herman, Robin; Johnston, Laurie (January 8, 1983). "New York Day by Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Barbanel, Josh (June 15, 1983). "Houses of Worship Take Landmark Fight to Albany". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Gottlieb, Martin (December 13, 1983). "Landmark Park Ave. Church Asks Permission to Change a Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Margolick, David (January 31, 1984). "Church's Fight on Landmarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2023.