Billings is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Montana, with a population of 117,116 as of the 2020 census.[4] Located in the south-central portion of the state, it is the seat of Yellowstone County and the principal city of the Billings Metropolitan Area, which had a population of 184,167 in the 2020 census.[5] With one of the largest trade areas in the United States,[6] Billings is the trade and distribution center for much of Montana east of the Continental Divide. Billings is also the largest retail destination for much of the same area. The Billings Chamber of Commerce claims the area of commerce covers more than 125,000 square miles (320,000 km2).[7] In 2009, it was estimated to serve over 500,000 people.[8]

Billings

Ammalapáshkuua É'êxováhtóva | |

|---|---|

Billings and surrounding area. | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): "Magic City", "City by the Rims", "Star of the Big Sky Country", "Montana's Trailhead" | |

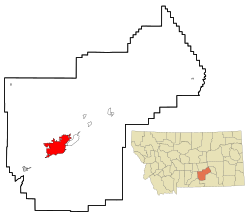

Location within Yellowstone County | |

| Coordinates: 45°47′01″N 108°30′22″W / 45.78361°N 108.50611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| County | Yellowstone |

| Founded | 1877 |

| Incorporated | March 24, 1882 |

| Named for | Frederick H. Billings |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Bill Cole |

| • City Admin. | Chris Kukulski |

| • Governing body | City Council |

| Area | |

| • City | 45.39 sq mi (117.57 km2) |

| • Land | 45.29 sq mi (117.29 km2) |

| • Water | 0.11 sq mi (0.28 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,124 ft (952 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 117,116 |

| • Rank | US: 242nd MT: 1st |

| • Density | 2,586.08/sq mi (998.50/km2) |

| • Urban | 114,773 (US: 273rd) |

| • Metro | 187,037 (US: 232nd) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (Mountain) |

| ZIP codes | 59101-59117[3] |

| Area code | 406 |

| FIPS code | 30-06550 |

| GNIS feature ID | 802034[2] |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

Billings was nicknamed the "Magic City" because of its rapid growth from its founding as a railroad town in March 1882. The nearby Crow and Cheyenne peoples called the city Ammalapáshkuua[9] and É'êxováhtóva[10] respectively, meaning 'where they cut wood', named as such because of a sawmill built in the area by early white settlers. The city has experienced rapid growth and maintains a strong economy. From 1969 to 2021, the Billings area population growth was 89%, compared to Montana's overall increase of 59%.[11] Parts of the metro area are seeing hyper growth. From 2000 to 2010 Lockwood, an eastern suburb, saw growth of 57.8%, the largest growth rate of any community in Montana.[12] In 2020, the area experienced its highest growth rate in a decade with a 2.3% increase.[13] Billings avoided the economic downturn that affected most of the nation from 2008 to 2012 as well as the housing bust.[14][15] With more hotel accommodations than any area within a five-state region, the city hosts a variety of conventions, concerts, sporting events, and other rallies.[6] With the nearby Bakken oil development, the largest oil discovery in U.S. history,[16][17] as well as the Heath Shale oil discovery north of Billings,[18] the city's growth rate stayed high during the shale oil boom.[19][20]

Attractions in and around Billings include ZooMontana, the Yellowstone Art Museum, Pompey's Pillar, Pictograph Cave, Chief Plenty Coups State Park, Little Bighorn Battlefield, Bighorn Canyon, Red Lodge Mountain, and the Beartooth Highway. The northeast entrance to Yellowstone National Park is a little over 100 miles (160 km) from Billings.

History edit

Name edit

The city is named for Frederick H. Billings, a former president of the Northern Pacific Railroad from Woodstock, Vermont. An earlier name for the area was Clark's Fork Bottom.

The Crow people from the nearby Crow Indian Reservation call the city Ammalapáshkuua. It means 'where they cut wood', and is named as such because of a sawmill built in the area by early white settlers.[21] The Cheyenne from the nearby Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation referred to the city as É'êxováhtóva, 'sawing place'[22] and the Gros Ventre from the nearby Fort Belknap Indian Reservation referred to it as ʔóhuutébiθɔnɔ́ɔ́nh, 'where they saw lumber',[23] both also named for the sawmill, or translations of the Crow name.

Prehistory edit

The downtown core and much of the rest of Billings is in the Yellowstone Valley, a canyon carved out by the Yellowstone River. Around 80 million years ago, the Billings area was on the shore of the Western Interior Seaway. The sea deposited sediment and sand around the shoreline. As the sea retreated, it left a deep layer of sand. Over millions of years, this sand was compressed into stone known as Eagle Sandstone. Over the last million years the river has carved its way down through this stone to form the canyon walls known as the Billings Rimrocks or the Rims.[24]

The Pictograph Caves are about five miles south of downtown. These caves contain over 100 pictographs (rock paintings), the oldest of which is over 2,000 years old. Approximately 30,000 artifacts (including stone tools and weapons) have been excavated from the site.[25] These excavations have proved the area has been occupied since at least 2600 BC until after 1800 AD.[26]

The Crow Indians have called the Billings area home since about 1700. The present-day Crow Nation is just south of Billings.[27]

Lewis and Clark Expedition edit

In July 1806, William Clark (of the Lewis and Clark Expedition) passed through the Billings area. On July 25 he arrived at what is now known as Pompey's Pillar and wrote in his journal "... at 4 P M arrived at a remarkable rock, i ascended this rock and from its top had a most extensive view in every direction."[28] Clark carved his name and the date into the rock, leaving the only remaining physical evidence of their expedition. He named the place Pompey's Tower, naming it after the son of his Shoshone interpreter and guide Sacajawea. In 1965, Pompey's Pillar was designated as a national historic landmark, and was proclaimed a national monument in January 2001. An interpretive center has been built next to the monument.[29]

Coulson/Billings edit

The area where Billings is today was known as Clark's Fork Bottom. Clark's Fork Bottom was to be the hub for hauling freight to Judith and Musselshell Basins. At the time these were some of the most productive areas of the Montana Territory. The plan was to run freight up Alkali Creek, now part of Billings Heights, to the basins and Fort Benton on the Hi-Line.[citation needed]

In 1877, settlers from the Gallatin Valley area of the Montana Territory formed Coulson the first town of the Yellowstone Valley.[30] The town was started when John Alderson built a sawmill and convinced PW McAdow to open a general store and trading post on land Alderson owned on the bank of the Yellowstone River. The store went by the name of Headquarters, and soon other buildings and tents were being built as the town began to grow. At this time before the coming of the railroad, most goods coming to and going from the Montana Territory were carried on paddle riverboats. It is believed it was decided to name the new town Coulson in an attempt to attract the Coulson Packet Company that ran riverboats between St Louis and many points in the Montana Territory. In spite of their efforts the river was traversed only once by paddle riverboat to the point of the new town.

Coulson was a rough town of dance halls and saloons and not a single church. The town needed a sheriff and the famous mountain man John "Liver-Eating" Johnson took the job. Many disagreements were settled with a gun in the coarse Wild West town. Soon a graveyard was needed and Boothill Cemetery was created. It was called Boothill because most of the people in it were said to have died with their boots on. Today, Boothill Cemetery sits within Billings' city limits and is the only remaining physical evidence of Coulson's existence.

When the railroad came to the area, Coulson residents were sure the town would become the railroads hub and Coulson would soon be the Territories largest city. The railroad only had claim to odd sections and it had two sections side-by-side about two miles west of Coulson. Being able to make far more money by creating a new town on these two sections the railroad decided to create the new town of Billings, the two towns existed side by side for a short time with a trolley even running between them. However, most of Coulson's residents moved to the new booming town of Billings. In the end Coulson faded away with the last remains of the town disappearing in the 1930s. Today Coulson Park, a Billings city park, sits on the river bank where Coulson once was.[31]

Early railroad town edit

Named after the Northern Pacific Railway president Frederick H. Billings, the city was founded in 1882.[32][33] The Railroad formed the city as a western railhead for its further westward expansion. At first the new town had only three buildings but within just a few months it had grown to over 2,000. This spurred Billings' nickname of the Magic City because, like magic, it seemed to appear overnight.[30][34]

The nearby town of Coulson appeared a far more likely site. Coulson was a rough-and-tumble town where arguments were often followed by gunplay. Liver-Eating Johnson was a lawman in Coulson.[35] Perhaps the most famous person to be buried in Coulson's Boothill cemetery is H.M. "Muggins" Taylor,[36] the scout who carried the news of Custer's Last Stand at the Battle of Little Bighorn to the world. Most buried here were said to have died with their boots on. The town of Coulson had been on the Yellowstone River, which made it ideal for the commerce steamboats brought up the river. However, when the Montana & Minnesota Land Company oversaw the development of potential railroad land, they ignored Coulson, and platted the new town of Billings just a couple of miles to the northwest. Coulson quickly faded away; most of her residents were absorbed into Billings. Yet, for a short time, the two towns coexisted; a trolley even ran between them. But ultimately there was no future for Coulson as Billings grew. Though it stood on the banks of the Yellowstone River only a couple of miles from the heart of present-day downtown Billings, the city of Billings never built on the land where Coulson once stood. Today Coulson Park sits along the banks of the Yellowstone where the valley's first town once stood.[30]

20th century edit

By the 1910 census, Billings' population had risen to 10,031, ranking it the sixth fastest-growing community in the nation.[30] Billings became an energy center in the early years of the twentieth century with the discovery of oil fields in Montana and Wyoming. Then the discovery of large natural gas and coal reserves secured the city's rank as first in energy.[30] In the early 20th century, its served as regional trading center and energy hub for eastern Montana and northern Wyoming, an area then known as the Midland Empire.

After World War II, Billings became the region's major financial, medical and cultural center. Billings has had rapid growth from its founding; in its first 50 years growth was, at times, as high as 200 to 300 percent per decade.[38]

Billings growth has remained robust throughout the years. In the 1950s, it growth rate was 66 percent.[39] The 1973 oil embargo by OPEC spurred an oil boom in eastern Montana, northern Wyoming and western North Dakota. With this increase in oil production, Billings became the headquarters for energy sector companies. In 1975 and 1976, the Colstrip coal-fire generation plants 1 and 2 were completed; plants 3 and 4 started operating in 1984 and 1986.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Billings saw major growth in its downtown core; the first high-rise buildings to be built in Montana were erected. In 1980, the 22-floor Sheraton Hotel was completed. Upon its completion, it was declared "the tallest load-bearing brick masonry building in the world" by the Brick Institute of America.[40] During the 1970s and 1980s, other major buildings were constructed in the downtown core;[41] the Norwest Building (now Wells Fargo), Granite Tower, Sage Tower, the MetraPark arena, the TransWestern Center, many new city-owned parking garages, and the First Interstate Center, the tallest building in a five-state area.[42]

With the completion of large sections of the interstate system in Montana in the 1970s, Billings became a shopping destination for an ever-larger area. The 1970s and 1980s saw new shopping districts and shopping centers developed in the Billings area. In addition to the other shopping centers, two new malls were developed, and Rimrock Mall was redeveloped and enlarged, on what was then the city's west end. Cross Roads Mall was built in Billings Heights, and West Park Plaza mall in midtown. Several new business parks were also developed on the city's west end during this period.

Billings was affected by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in May; the city received about 1-inch (25 mm) of ash on the ground.[43] The Yellowstone fires of 1988 blanketed Billings in smoke for weeks.[44]

In the 1990s, the service sector in the city increased with the development of new shopping centers built around big box stores which built multiple outlets in the Billings area. With the addition of more interchange exits along I-90, additional hotel chains and service industry outlets are being built in Billings. Development of business parks and large residential developments on the city's west end, South Hills area, Lockwood, and the Billings Heights were all part of the 1990s. Billings received the All-America City Award in 1992.

21st century edit

In the 21st century, Billings saw the development of operations centers in the city's business parks and downtown core by such national companies as GE, Wells Fargo, and First Interstate Bank. The Downtown Billings Alliance led efforts to transform downtown in order to increase economic and civic opportunities.[45] In 2002, Skypoint was completed. This artistic structure provides a defining area to host events. Downtown saw a renaissance of the historic area as building after building was restored.[46] In 2007, Billings was designated a Preserve America Community.[47]

Various changes were made to make the city more environmentally friendly. The MET Transit Center for city buses received LEED Platinum status in 2010. This was the first transportation facility in the US to do so.[48] In 2022, Billings received LEED Gold certification, the first city to do so in Montana and the 21st globally.[49] Projects to achieve this status included increased efficiency at the water and waste water treatment plant, adding electric city buses and EV charging stations, and adding a conservation area to the west-end.[49]

Significant road developments began, providing infrastructure for city growth. In 2000, a new exit on Interstate 90 was completed. Zoo Drive exit provides ease of access to the quickly growing west-end area.[50] The Yellowstone River bridge is being rebuilt as part of the Billings Bypass project, which will create a new arterial roadway from Lockwood to the Heights.[51][52]

The city saw a significant growth in businesses. With the completion of the Shiloh interchange exit, the TransTech Center was developed[53] and more hotels were built. In 2010 the Shiloh corridor was open for business with the completion of the Shiloh parkway, a 4.8-mile (7.7 km) multi-lane street with eight roundabouts.[54] Other new centers include Billings Town Square and West Park Promenade, Montana's first open-air shopping mall. In 2009, Fortune Small Business magazine named Billings the best small city in which to start a business.[8][55]

On June 20, 2010 (Father's Day), a tornado touched down in the downtown core and Heights sections of Billings. The MetraPark Arena and area businesses suffered major damage.

In the 2010s, Eastern Montana and North Dakota experienced an energy boom due to the Bakken formation, the largest oil discovery in U.S. history.[16][17]

Geography edit

Two-thirds of the city is in the Yellowstone Valley and the South Hills area and one-third in the Heights-Lockwood area. The city is divided by the Rims, long cliffs, also called the Rimrocks. The Rims run to the north and east of the downtown core, separating it from the Heights to the north and Lockwood to the east, with the cliffs to the north being 500 feet (150 m) tall and to the east of downtown, the face rises 800 feet (240 m). The elevation of Billings is 3,126 feet (953 m) above sea level. The Yellowstone River runs through the southeast portion of the city. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 43.52 square miles (112.72 km2), of which 43.41 square miles (112.43 km2) is land and 0.11 square miles (0.28 km2) is water.[56]

Around Billings, seven mountain ranges can be viewed. The Bighorn Mountains have over 200 lakes and two peaks that rise to over 13,000 feet (4,000 m): Cloud Peak, at 13,167 ft (4,013 m) and Black Tooth Mountain, at 13,005 ft (3,964 m).[57] The Pryor Mountains directly south of Billings rise to a height of 8,822 feet (2,689 m) and are unlike any other landscape in Montana. They are also home the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range.[58] The Beartooth Mountains are the location of Granite Peak, which at 12,807 feet (3,904 m) is the highest point in the state of Montana. The Beartooth Highway, a series of steep zigzags and switchbacks along the Montana–Wyoming border, rises to 10,947 feet (3,337 m). It was called "the most beautiful drive in America" by Charles Kuralt.[59] The Beartooth Mountains are just northeast of Yellowstone National Park. The Crazy Mountains to the west rise to a height of 11,209 feet (3,417 m) at Crazy Peak, the tallest peak in the range.[60] Big Snowy Mountains, with peaks of 8,600 feet (2,600 m), are home to Crystal Lake.[61] The Bull Mountains are a low-lying heavily forested range north of Billings Heights. The Absaroka Range[62] stretches about 150 mi (240 km) across the Montana–Wyoming border, and 75 miles (121 km) at its widest, forming the eastern boundary of Yellowstone National Park.

Climate edit

Downtown Billings has a cold semi arid climate (Köppen: Bsk ),[63] with dry, hot summers, and cold, dry winters. However, areas outside of downtown can have a hot-summer continental climate, even with the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm, due to the urban heat island effect, as exemplified by the Billings Logan International Airport. In the summer, the temperature can rise to over 100 °F (37.8 °C) on an average of 1 to 3 days per year, while the winter will bring temperatures below 0 °F or −17.8 °C on an average of 12.9 days per year. The snowfall averages 57.4 inches (146 cm) a year, but because of warm chinook winds that pass through the region during the winter, snow does not usually accumulate heavily or remain on the ground for long: the greatest depth has been 33 inches (84 cm) on April 5, 1955, after a huge storm which dumped 4.22 inches (107 mm) of water equivalent precipitation as snow in the previous three days under temperatures averaging 26.7 °F (−2.9 °C).

The snowiest year on record was 2017–18, with 106.1 inches (269 cm), topping the 2013–14 previous record of 103.5 inches (263 cm). The first freeze of the season on average arrives by October 6 and the last is May 5. Spring and autumn in Billings are usually mild, but brief. Winds, while strong at times, are considered light compared with the rest of Montana and the Rocky Mountain Front.

Due to its location, Billings is susceptible to severe summer weather as well. On June 20, 2010, a tornado touched down in the Billings Heights and Downtown sections of the city. The tornado was accompanied by hail up to golf ball size, dangerous cloud-to-ground lightning, and heavy winds. The tornado destroyed a number of businesses and severely damaged the 12,000-seat MetraPark Arena.[64]

| Climate data for Billings, Montana (Billings Logan International Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1934–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

72 (22) |

80 (27) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

105 (41) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

91 (33) |

77 (25) |

73 (23) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56.3 (13.5) |

59.7 (15.4) |

70.1 (21.2) |

79.0 (26.1) |

85.8 (29.9) |

94.1 (34.5) |

99.9 (37.7) |

98.4 (36.9) |

93.0 (33.9) |

81.3 (27.4) |

67.3 (19.6) |

56.2 (13.4) |

101.1 (38.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.0 (2.2) |

39.2 (4.0) |

49.0 (9.4) |

56.9 (13.8) |

66.9 (19.4) |

77.0 (25.0) |

87.3 (30.7) |

85.8 (29.9) |

74.3 (23.5) |

58.8 (14.9) |

45.7 (7.6) |

36.1 (2.3) |

59.4 (15.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 27.0 (−2.8) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

38.0 (3.3) |

45.8 (7.7) |

55.3 (12.9) |

64.7 (18.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

71.6 (22.0) |

61.4 (16.3) |

47.9 (8.8) |

36.2 (2.3) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

48.2 (9.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 17.9 (−7.8) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

34.7 (1.5) |

43.8 (6.6) |

52.4 (11.3) |

59.3 (15.2) |

57.5 (14.2) |

48.6 (9.2) |

37.1 (2.8) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

19.2 (−7.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −7.4 (−21.9) |

−2.3 (−19.1) |

5.9 (−14.5) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

41.3 (5.2) |

50.6 (10.3) |

46.5 (8.1) |

35.1 (1.7) |

18.4 (−7.6) |

4.5 (−15.3) |

−4.0 (−20.0) |

−15.7 (−26.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −30 (−34) |

−38 (−39) |

−21 (−29) |

−5 (−21) |

14 (−10) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

35 (2) |

22 (−6) |

−7 (−22) |

−22 (−30) |

−32 (−36) |

−38 (−39) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.55 (14) |

0.57 (14) |

0.90 (23) |

1.72 (44) |

2.36 (60) |

2.22 (56) |

1.22 (31) |

0.87 (22) |

1.36 (35) |

1.37 (35) |

0.60 (15) |

0.57 (14) |

14.31 (363) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 10.6 (27) |

9.1 (23) |

8.2 (21) |

7.5 (19) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

4.5 (11) |

6.5 (17) |

9.8 (25) |

57.4 (146) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.6 | 6.9 | 8.6 | 10.4 | 12.2 | 11.2 | 7.7 | 6.0 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 56.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.8 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 38.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60.2 | 59.3 | 58.2 | 53.8 | 54.9 | 53.3 | 45.6 | 44.5 | 51.6 | 52.7 | 59.4 | 60.9 | 54.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 9.9 (−12.3) |

14.7 (−9.6) |

19.8 (−6.8) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

36.3 (2.4) |

44.6 (7.0) |

47.1 (8.4) |

44.6 (7.0) |

38.1 (3.4) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

20.1 (−6.6) |

12.4 (−10.9) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 130.2 | 156.6 | 236.5 | 255.5 | 282.0 | 304.7 | 355.4 | 329.0 | 255.8 | 203.2 | 127.6 | 116.4 | 2,752.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 46 | 54 | 64 | 63 | 61 | 65 | 75 | 75 | 68 | 60 | 45 | 43 | 62 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew points and sun 1961–1990)[65][66] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[67] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Billings Water Treatment Plant, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1894–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

99 (37) |

108 (42) |

112 (44) |

107 (42) |

101 (38) |

95 (35) |

80 (27) |

75 (24) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57.4 (14.1) |

61.4 (16.3) |

72.1 (22.3) |

80.8 (27.1) |

86.4 (30.2) |

94.4 (34.7) |

99.4 (37.4) |

98.5 (36.9) |

94.3 (34.6) |

83.2 (28.4) |

69.0 (20.6) |

57.7 (14.3) |

100.5 (38.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.5 (2.5) |

40.6 (4.8) |

50.9 (10.5) |

58.6 (14.8) |

67.6 (19.8) |

76.9 (24.9) |

86.3 (30.2) |

85.4 (29.7) |

75.2 (24.0) |

60.4 (15.8) |

46.5 (8.1) |

36.8 (2.7) |

60.1 (15.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.4 (−3.7) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

37.8 (3.2) |

45.8 (7.7) |

54.7 (12.6) |

63.7 (17.6) |

71.2 (21.8) |

69.6 (20.9) |

60.1 (15.6) |

47.3 (8.5) |

35.1 (1.7) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

47.2 (8.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.4 (−9.8) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

33.1 (0.6) |

41.9 (5.5) |

50.4 (10.2) |

56.2 (13.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

45.0 (7.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

15.8 (−9.0) |

34.2 (1.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −11.2 (−24.0) |

−4.1 (−20.1) |

4.8 (−15.1) |

20.3 (−6.5) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

39.5 (4.2) |

48.2 (9.0) |

44.7 (7.1) |

33.4 (0.8) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

3.1 (−16.1) |

−6.3 (−21.3) |

−18.8 (−28.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −39 (−39) |

−49 (−45) |

−34 (−37) |

−5 (−21) |

14 (−10) |

26 (−3) |

37 (3) |

28 (−2) |

18 (−8) |

−11 (−24) |

−28 (−33) |

−41 (−41) |

−49 (−45) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.56 (14) |

0.57 (14) |

0.97 (25) |

1.88 (48) |

2.47 (63) |

2.45 (62) |

1.31 (33) |

0.80 (20) |

1.52 (39) |

1.60 (41) |

0.68 (17) |

0.62 (16) |

15.43 (392) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.5 (19) |

4.7 (12) |

4.9 (12) |

3.2 (8.1) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.7 (4.3) |

3.1 (7.9) |

9.8 (25) |

35.0 (89) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.0 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 8.9 | 10.7 | 10.4 | 6.9 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 81.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.5 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 18.7 |

| Source 1: NOAA[68] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[67] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Sections edit

Billings has many sections that comprise the whole of the city. The sections are often defined by Billings unique physical characteristics. For example, a 500-foot (150 m) cliff known as the "Rims" separates the Heights from downtown Billings.

There are 11 boroughs called "sections" within Billings' city limits.

Neighborhoods and zones edit

The south side of Billings is probably the oldest residential area in the city, and it is the city's most culturally diverse neighborhood. South Park is an old-growth City park, host to several food fairs and festivals in the summer months. The Bottom Westend Historic District is home to many of Billings' first mansions. Midtown, the most densely populated portion of the city is in the midst of gentrification on a level few, if any, areas in Montana have ever seen. New growth is mainly concentrated on Billings West End, where Shiloh Crossing is a new commercial development, anchored by Scheels, Montana's largest retail store. Residentially, the West End is characterized by upper income households. Denser, more urban growth is occurring in Josephine Crossing, one of Billings' many new contemporary neighborhoods. Downtown is a blend of small businesses and office space, together with restaurants and a walkable brewery district.[69] The Heights, defined as the area of the city northeast of the Metra, is predominantly residential, and a new school was recently completed in 2016 to accommodate growth in the neighborhood.[70]

Surrounding areas edit

Billings is the principal city of the Billings Metropolitan Statistical Area. The metropolitan area consists of three counties: Yellowstone, Stillwater, and Carbon.[71] The population of the entire metropolitan area was at 184,167 in the 2020 Census.[72]

Demographics edit

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 145 | — | |

| 1880 | 587 | 304.8% | |

| 1890 | 836 | 42.4% | |

| 1900 | 3,211 | 284.1% | |

| 1910 | 10,031 | 212.4% | |

| 1920 | 15,100 | 50.5% | |

| 1930 | 16,386 | 8.5% | |

| 1940 | 23,216 | 41.7% | |

| 1950 | 31,834 | 37.1% | |

| 1960 | 52,851 | 66.0% | |

| 1970 | 61,581 | 16.5% | |

| 1980 | 66,798 | 8.5% | |

| 1990 | 81,151 | 21.5% | |

| 2000 | 89,847 | 10.7% | |

| 2010 | 104,170 | 15.9% | |

| 2020 | 117,116 | 12.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[73] 2020 Census[4] | |||

2010 census edit

As of the census[74] of 2010, there were 104,170 people, 43,945 households, and 26,194 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,399.7 inhabitants per square mile (926.5/km2). There were 46,317 housing units at an average density of 1,067.0 per square mile (412.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.6% White, 4.4% Native American, 0.8% Black, 0.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.4% from other races, and 2.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.2% of the population.

There were 43,945 households, of which 28.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.7% were married couples living together, 11.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.4% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.90.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 22.6% of residents under the age of 18; 9.8% between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.3% from 25 to 44; 26.3% from 45 to 64; and 15% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age in the city was 37.5 years. The gender makeup of the city was 48.3% male and 51.7% female.

Income edit

As of 2000 the median income for a household in the city was $35,147, and the median income for a family was $45,032. The per capita income for the city was $19,207. As of 2021, the median household income had risen to $63,608, slightly higher than the statewide median income of $60,560. Per capita income was $37,976. About 9.2% of families and 11.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.5% of those under age 18 and 7.0% of those age 65 or over. 36.6% of the population has a bachelor's degree or higher.

Economy edit

Billings' location was essential to its initial economic success. Billings' future as a major trade and distribution center was basically assured from its founding as a railroad hub due to its geographic location. As Billings quickly became the region's economic hub, it outgrew the other cities in the region. The Billings trade area serves over a half million people.[8] A major trade and distribution center, the city is home to many regional headquarters and corporate headquarters. Because Montana has no sales tax, Billings is a retail destination for much of Wyoming, North and South Dakota as well as much of Montana east of the Continental Divide. $1 out of every $7 spent on retail purchases in Montana is spent in Billings. The percentage of wholesale business transactions done in Billings is even stronger: Billings accounts for more than a quarter of the wholesale business for the entire state (these figures do not include Billings portion of sales for Wyoming and the Dakotas).[75] Billings is an energy center because it sits amidst the largest coal reserves in the United States, as well as large oil and natural gas fields.

In 2009, Fortune Small Business magazine named Billings the best small city in which to start a business.[55] Billings has a diverse economy including a large and rapidly growing medical corridor that includes inpatient and outpatient health care. Billings has a large service sector including retail, hospitality and entertainment. The metro area is also home to commercial and residential construction, building materials manufacturing and distribution, professional services, financial services, banking, trucking, higher education (4 campuses, 19 others have a physical presence/classes), auto parts wholesaling and repair services, passenger and cargo air, cattle, media, printing, heavy equipment sales and service, business services, consumer services, food distribution, agricultural chemical manufacturing and distribution, energy exploration and production, surface and underground mining, and metal fabrication, providing a diverse and robust economy.

Agriculture is Montana's #1 industry.[76] Billings contributes to this economy with the Western Sugar Cooperative Plant, processing multi-million dollar crops of sugar beets each year.[7] Other crops include alfalfa, wheat, barley, and corn.[77] Billings has 2 livestock auction locations out of the 13 statewide.[78] Several farm and ranch supply stores are located in Billings, providing for the large retail radius the city serves. Meadow Gold has a milk processing center in the town.

Billings plays a vital part in the energy sector. Out of Montana's 4 oil refineries, 3 of those are in Yellowstone County.[79] Montana has about three-tenths of the nation's estimated recoverable coal reserves.[79] In 2022, a large pumped hydro storage project was planned near Billings.[79]

Corporate headquarters include Kampgrounds of America, First Interstate Bank,[6] and The Waggoners Trucking.[80] Billings also has a nearby facility for Molson Coors,[77] a manufacturing facility for Coca-Cola,[81] and several other food and beverage distributors. Some major employers include St. John's Lutheran Ministries, Avitus Group, Franz Bakery, and Komatsu.

Arts and culture edit

Museums edit

- Moss Mansion Historic House Museum

- Western Heritage Center

- Wise Wonders Children's Museum

- Yellowstone Art Museum

- Yellowstone County Museum

Historic Areas edit

- Billings Depot

- Downtown Historic District

- Boothill Cemetery

- Black Otter Trail

- Yellowstone Kelly's Grave

Zoos edit

- ZooMontana, 70-acre (28 ha) zoo and botanical garden

Venues edit

MetraPark edit

MetraPark, currently called "First Interstate Arena at MetraPark" due to sponsorship, is a 12,000-seat multi-purpose building that was completed in 1975. METRA stands for "Montana Entertainment Trade and Recreation Arena". It is the largest indoor venue in Montana and is used for concerts, rodeos, ice shows, motor sports events, and more.[82]

Alberta Bair Theater edit

The Alberta Bair Theater is a 1,400-seat performing arts venue noted for its 20-ton capacity hydraulic lift that raises and lowers the stage apron.[83] Opened in 1931 and originally called the Fox Theater, it was renamed in 1987 in honor of Alberta Bair and her substantial donations that helped fund the building's renovation.

Eagle Seeker Community Center edit

Built in 1950, the Eagle Seeker Community Center (formerly the Shrine Auditorium) is a smaller, cost-effective venue that has hosted national shows. It seats 2,340 for concerts and offers 550 off-street parking spots.

Dehler Park edit

Dehler Park is a multi-use stadium that is home of the Billings Mustangs, a Pioneer League baseball team. It replaced Cobb Field and Athletic Park swimming pool in the summer of 2008. Dehler Park has a capacity of 3,500 to over 6,000.

Wendy's Field edit

Wendy's Field at Daylis Stadium is a local stadium used for high school games. It is next to Billings Senior High.

Centennial Ice Arena edit

Centennial Ice Arena is home to the Billings Amateur Hockey League, Figure Skating Clubs and Adult Hockey.

Babcock Theater edit

The Babcock Theater is a 750-seat performing arts theater in Billings, Montana. It was built in 1907 and at the time was considered the largest theater between Minneapolis and Seattle. Purchased by the City of Billings in 2018,[84] it hosts events and shows movies by Art House Cinema.

Alterowitz Arena edit

This 4,000-seat venue primarily hosts MSU Billings sports, local events, and some national touring events. This facility has gyms, racket ball courts as well as an Olympic-size pool with bleachers for aquatic events.

Fortin Center edit

Fortin Center is a 3,000-seat arena on the campus of Rocky Mountain College used primarily for the college's sporting events.

Arts edit

- Backyard Theatre

- Billings Public Library[85]

- Billings Studio Theater

- Billings Symphony Orchestra

- Billings Youth Orchestra

- NOVA: Performing Arts Center

- Sacrifice Cliff Theatre Co.

- Yellowstone Chamber Players

- Yellowstone Repertory Theatre

Events edit

- Pride Week (some years)[86][87]

- MontanaFair (August) at the MetraPark fairgrounds[88]

- Billings Artwalk (first Friday of every other month at downtown businesses)[89]

- Strawberry Festival[90]

Breweries and distilleries edit

With nine microbreweries in the metropolitan area, Billings has more breweries than any community in Montana. The downtown breweries include Montana Brewing Co., Thirsty Street Tap Room, Angry Hank's Tap Room, Carters Brewery, and Überbrew.[91] Downtown Billings is also home to two distilleries, offering a variety of handcrafted spirits & cocktails. On the city's West End, you'll find several other breweries and a third distillery.[92] The Billings Brew Trail[93] features all of the distilleries & breweries across the city, as well as a cider house and a winery. The downtown portion of the Brew Trail features the largest walkable brewery district in Montana.

Sports edit

- Billings Mustangs, an independent Pioneer League baseball team that was formerly (up through 2020) affiliated with the Cincinnati Reds

- Billings Outlaws, a CIF indoor football team that plays at First Interstate Arena.

- The NILE (Northern International Livestock Exposition) Rodeo at First Interstate Arena

- Great American Championship Motorcycle Hill Climb, billed as "The Oldest, Richest and Biggest Motorcycle Hill Climb in the United States"

Parks and recreation edit

- Lake Elmo State Park

- Rimrocks ("The Rims")

- Skypoint

- Yellowstone Kelly Interpretive Site[94]

- Zimmerman Park

Government edit

| Mayor | Bill Cole |

| Ward 1 | Ed Gulick / Kendra Shaw |

| Ward 2 | Jennifer Owen / Roy Neese |

| Ward 3 | Denise Joy / Bill Kennedy |

| Ward 4 | Scott Aspenlieder[96] / Dan Tidswell |

| Ward 5 | Mike Boyett / Tom Rupsis |

Billings is the county seat of Yellowstone County, the most populous county in Montana.[97] It is also the location of the James F. Battin Federal Courthouse, one of five federal courthouses for the District of Montana.[98]

Billings is governed via the mayor council system. There are ten members of the city council who are elected from one of five wards with each ward electing two members. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote. Both the mayor and council members are officially nonpartisan. The city charter, also called the Billings, Montana City Code (BMCC) was established 1977.

Unlike some other cities in Montana, Billings' city ordinances do not contain provisions that forbid discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[99] An effort to pass a non-discrimination ordinance in Billings failed in 2014, after then-mayor Tom Hanel cast a tie-breaking vote against it at the conclusion of a meeting that lasted 8.5 hours.[100] An effort to introduce an NDO measure to the City Council was briefly floated in September 2019 by a city council member,[101] but was abandoned approximately a month later.[99]

Education edit

Primary and secondary edit

Public edit

Billings Public Schools has two components: Billings Elementary School District and Billings High School District.[102]

There are six elementary school districts covering portions of Billings: Most of it is in Billings Elementary School District, and other portions are in: Elysian Elementary School District, Elder Grove Elementary School District, Canyon Creek Elementary School District, Blue Creek Elementary School District, and Independent Elementary School District. All of Billings is in Billings High School District.[103]

Billings Public Schools consists of 22 elementary schools, six middle schools, and three high schools (Senior High, Skyview High, and West High) that have approximately 15,715 students and 1,850 full-time employees.[104] District 3, Independent, and Elder Grove School Districts each have one elementary school, those being Blue Creek Elementary,[105] Elder Grove Elementary,[106] and Independent Elementary, respectively. Canyon Creek School District operates Canyon Creek School, which serves grades K-8.

Private edit

- Billings Catholic Schools

- Billings Central Catholic High School (grades 9–12)

- St. Francis Catholic School (grades K–8)

- St. Francis Daycare

- Trinity Lutheran School (grades K–8)

- Billings Christian Schools (grades Pre–12)

- Billings Educational Academy (grades K–12)

- Grace Montessori Academy (grades Pre–8)[107]

- Sunrise Montessori (grades Pre–5)

Colleges and universities edit

Billings has three institutions of higher learning. Montana State University Billings (MSU Billings) is part of the state university system, while Rocky Mountain College and Rocky Vista University are private.

Public edit

Montana State University Billings was founded in 1927 as Eastern Montana Normal College to train teachers. The name was shortened to Eastern Montana College in 1949, and it was given its present name when the Montana State University System reorganized in 1994.[108] The university offers associate/bachelor's/master's degrees and certificates in fields such as business, education, and medicine.[109] Around 4,000 students attend MSU Billings.[110]

City College at MSU Billings was established in 1969 as the Billings Vocational-Technical Education Center. Its governance was passed to the Montana University System Board of Regents in 1987, when it became known as the College of Technology. It was officially merged with MSU Billings (then known as Eastern Montana College) in 1994.[111] The name was changed to the present name in 2012.[112] Known as the "comprehensive two-year college arm" of MSU Billings,[113] the college offers degrees and programs in a variety of fields, including automotive, business, computer technology, and nursing.[114]

Private edit

Through the marriage of three institutions of higher learning, Rocky Mountain College is Montana's oldest college. Rocky Mountain College (RMC) was founded in 1878.[115] The campus that became RMC was known as the Billings Polytechnic Institute until 1947, when it joined the Montana Collegiate Institute in Deer Lodge (Montana's first institution of higher learning) and Intermountain Union College in Helena to form to Rocky Mountain College.[116] During the 2013 fall semester, there were 1,068 students attending Rocky Mountain College.[117] The college offers 50 majors offered in 24 different fields including art, education, music, psychology, and theater.[118] RMC is affiliated with the United Church of Christ, the United Methodist Church, and the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.).[119]

Rocky Vista University, a private for-profit school of osteopathic medicine, operates the Montana College of Osteopathic Medicine. The campus, completed in 2023, is located in western Billings. Classes began the same year.[120] The university later announced plans to establish a College of Veterinary Medicine at the Billings campus by 2026.[121]

Yellowstone Christian College was headquartered in Billings from 1974 to 2021, when it moved to Kalispell.[122]

Media edit

Newspapers edit

The largest media market in Montana and Wyoming, Billings is serviced by a variety of print media. Newspaper service includes the Billings Gazette, a daily morning broadsheet newspaper printed in Billings, Montana, and owned by Lee Enterprises. It is the largest daily newspaper in Montana, with a Sunday circulation of 52,000 and a weekday circulation of 47,000. It publishes three editions: the state edition, which circulates in most of Eastern Montana and all of South Central Montana; the Wyoming edition, which circulates in Northern Wyoming; and the city edition, which circulates in Yellowstone County.

Yellowstone County News is the next leading print newspaper, owned by Jonathan & Tana McNiven.[123] It is published on a weekly basis and provides news and columns for "Yellowstone County and the communities of Lockwood, Shepherd, Huntley, Worden, Ballanatine, Pompey's Pillar, Custer and Billings."[124] It is also recognized as the Publication of Record for both the City of Billings and Yellowstone County.[125]

Other publications include other more specialized weekly and monthly publications, like the Billings Times, a weekly legal/statistical newspaper.[126]

Magazines edit

Billings has several community magazines including Magic City Magazine,[127] which features local feature stories and unique human interest pieces,[128] and Yellowstone Valley Woman.[129] The Billings Beet provides the region with satirical news.

Television and radio edit

The Billings area has four major non-news television stations, two major news television stations, one community television station, four PBS channels[130] and several Low-Power Television (LPTV) channels. The major TV stations include KTVQ channel 2 (CBS affiliate and part of the Montana Television Network [MTN]), KHMT channel 4 (FOX affiliate), KSVI channel 6 (ABC affiliate with The CW on DT2), KULR-TV channel 8 (NBC affiliate) and PBS member station KBGS-TV on channel 16.

It is also served by twenty-two commercial radio stations, Yellowstone Public Radio (NPR),[131] and a Low-Power (LP) radio station. KFHW-LP is a radio station at 101.1 FM in Billings, an extension of the Yellowstone County News, also known as "YCN Radio" and/or "YCN Sports & Radio."[132]

Infrastructure edit

The Billings Canal (aka, The Big Ditch), used for irrigation, runs through Billings.

Transportation edit

Airports edit

Billings Logan International Airport is close to downtown; it sits on top of the Rims, a 500-foot (150 m) cliff that overlooks the downtown core. Scheduled passenger service and air cargo flights operate from this airfield.

The Laurel Municipal Airport is a publicly owned public-use airport in Laurel, Montana, eleven miles (18 km) southwest of downtown Billings. It has three runways exclusively serving privately operated general aviation aircraft and helicopters.[133]

Public transportation edit

The Billings METropolitan Transit is Billings' public transit system. MET Transit provides fixed-route and paratransit bus service to the City of Billings. All MET buses are accessible by citizens who use wheelchairs and other mobility devices. They are wheelchair lift-equipped and accessible to all citizens who are unable to use the stairs. MET buses are equipped with bike racks for their bike-riding passengers. There are Westend and Downtown transit centers allowing passengers to connect with all routes.[134] The Billings Bus Terminal is served by Express Arrow, Greyhound, and Jefferson Lines, which also provide regional and interstate bus service.[135]

Trail system edit

Billings has an extensive trail system running throughout the metro area. The rapidly expanding trail system, known as the Heritage trail system, has a large variety of well-maintained trails and pathways.[136]

Bicycling magazine ranked Billings among the nation's 50 most bike-friendly communities.[137] In 2012, the Swords Park Trail was named the Montana State Trail of the Year and received an Environmental and Wildlife Compatibility award from the Coalition for Recreational Parks.[138]

Highways edit

Interstate 90 runs east–west through the southern portion of Billings, serving as a corridor between Billings Heights, Lockwood, Downtown, South Hills, Westend, Shiloh, and Laurel. East of Downtown, between Billings Heights and Lockwood, Interstate 90 connects with Interstate 94, which serves as an east–west corridor between Shepherd, Huntley, Lockwood, Downtown, South Hills, Westend, Shiloh, and Laurel via its connection with I-90.

Montana Highway 3 is a north–south highway that runs along the edge of the North Rims connecting Downtown and the West End with the Rehberg Ranch, Indian Cliffs and Billings Heights. U.S. Highway 87 runs through the center of Billings Heights and is known as Main Street within the city limits. This is the busiest section of roadway in the state of Montana.[139] It connects to U.S. Highway 87 East, which runs through Lockwood as Old Hardin Road.[140]

The 2012 Billings area I-90 corridor planning study recommended many improvements to the corridor from Laurel through Lockwood, such as the addition of lanes and the reconstruction of many of the bridges, interchanges and on-off ramps.[141] These recommendations are being implemented via the I-90 Yellowstone River Project, which will widen the corridor to three lanes between the North 27th Street and Lockwood interchanges,[142] and the East Laurel–West Billings project, which includes multiple upgrades between the Mossman (East Laurel) and West Billings interchanges.[143] Both projects are slated for completion in 2024.

The Billings Bypass will create a new and more direct connection between the Billings Heights and Lockwood by connecting I-90 with Montana Highway 87 and Old Highway 312.[144] The project will include a new bridge over the Yellowstone River (completed in 2023) and the reconstruction of the I-90 Johnson Lane Interchange. The Billings Bypass is tentatively set for completion in 2027.[145]

Rail edit

There is currently no service, though until 1979 Amtrak's North Coast Hiawatha stopped at the Billings Depot, serving a Chicago to Seattle route. Before Amtrak, Billings was well-served by Northern Pacific, Great Northern, and Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy railroads with direct routes to Kansas City, Denver, Chicago, Great Falls, and the West Coast. (Billings was the northern and western terminus for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad).

The Big Sky Passenger Rail Authority was formed in 2020 to advocate for restoring Amtrak's North Coast Hiawatha route. In 2023, the organization was awarded $500,000 by the Corridor Identification and Development Program to explore the proposal's logistics and feasibility. The North Coast Hiawatha received further recognition from its identification in the 2024 Amtrak Daily Long-Distance Service Study.[146]

Healthcare edit

The city's rapidly growing health care sector employed nearly 13,000 people in 2012; they earned $641 million in wages, or about 20 percent of all wages in the city. Employment doubled in 25 years and wage rates in constant dollars grew by 162 percent.[147] The city has a Level II Trauma Center, St. Vincent Regional Hospital, as well as the first Level I Trauma Center in the region, Billings Clinic.

St. Vincent Regional Hospital was founded in 1898 by the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth as St. Vincent Hospital.[148] The name was changed to the present name in 2024.[149] In 2011, the hospital and its 30 clinics employed approximately 2,100 people and received more than 400,000 patient visits each year.[150] In 2022, the hospital announced plans to build a new 295-bed facility as a replacement for its current building.[151][152] It is the second largest hospital in the state, behind Billings Clinic. St. Vincent Regional Hospital is run by Intermountain Health,[153] which operates over 30 hospitals across the mountain west, including two others in Montana.

Billings Clinic started in 1911 as the general practice of Dr. Arthur J. Movius. By 1939, three new general practitioners had joined Dr. Movius's practice and the name was changed to The Billings Clinic. Billings Deaconess Hospital (founded in 1907) merged with Billings Clinic in 1990 to form the current hospital.[154] Billings Clinic now employs over 4,500 people,[155] including nearly 600 physicians, and is one of the largest employers in Montana.[156] In July 2012, Billings Clinic received a score of 72/100 for patient safety from Consumer Reports, making it the safest hospital of the 1,159 hospitals rated.[157] Additionally, in January 2013, Billings Clinic was added to the Mayo Clinic Care Network, only the 12th hospital nationally to be added to the network and the only such health system in Montana.[158] In 2023, Billings Clinic was named the Best Hospital in Montana by US News & World Report.[159] The same year, Billings Clinic became the first Level I Trauma Center in Montana and Wyoming.

Other medical facilities include the Northern Rockies Radiation Oncology Center, Rimrock Foundation (addiction treatment both inpatient and outpatient), Advanced Care Hospital of Montana (a 40-bed long-term acute-care hospital), South Central Montana Mental Health Center, Billings VA Community-Based Outpatient Clinic, Billings Clinic Research Center (pharmaceutical field trials, osteoporosis are two long-time focuses), Billings MRI, City/County Public Health's Riverstone Health, HealthSouth Surgery Center and Physical Therapy offices, Baxter/Travenol BioLife plasma collection center, and many independent practices.

Public safety edit

The Billings Police Department is the main law enforcement agency in Billings. It is the largest city police force in Montana, with about 162 sworn officers and 80 civilian employees. There are nine police beats.

The Billings Fire Department was founded in 1883 as a volunteer fire company named the Billings Fire Brigade. The Yellowstone Hook and Ladder Company was founded in 1886; that company was disbanded in 1888 after the mayor criticized the group for how that handled a fire, leaving the town without a fire department for almost six months.[160] The last volunteer fire company, Maverick Hose Company, served as the city's fire department until 1918.[161] The modern fire department has seven stations, employs 114 people, and received a class three rating by ISO.[162]

Notable people edit

More widely famous people who have lived in Billings include:

Historical edit

- Frank Borman, astronaut

- Albert D. Cooley, aviator and Lieutenant general, USMC; Navy Cross

- Will James, artist and author

- Calamity Jane, frontierswoman

- Terry C. Johnston, western novelist

- Charles Lindbergh, aviator

Sports edit

- Gary Albright, wrestler

- Carolin Babcock, tennis player

- Jeff Ballard, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Ed Breding, former NFL player

- Julie Brown, distance runner

- Kurt Burris, former NFL player

- Mike Burton, Olympic gold medalist in swimming

- Ruben Castillo, boxer

- Jim Creighton, former NBA player

- Mitch Donahue, former NFL player

- Dwan Edwards, NFL player

- Brad Holland, former NBA player

- Chris Horn, former AFL and NFL player

- Dave McNally, Major League Baseball pitcher

- Roy McPipe, former ABA player

- Andy Moog, former NHL player

- Brent Musburger, sportscaster

- Nich Pertuit, football player

- Kirk Scrafford, former NFL player

- Greg Smith, former NHL player

- Leslie Spalding, LPGA golfer

- Keith Wortman, former NFL player

Arts and entertainment edit

- Carson Allen, singer and musician

- Phil Amato, television host

- Stanley Anderson, actor

- Katie Blair, Miss Montana Teen USA 2006, Miss Teen USA 2006

- John Dahl, movie director

- Annie Duke, professional poker player and author

- Bob Enevoldsen, jazz multi-instrumentalist

- Andrea Fraser, artist

- Arlo Guthrie, folk singer

- Ethel Hays, cartoonist and illustrator

- David T. Hanson, environmental photographer

- Will James, western artist

- Brandon Jovanovich, opera singer

- Wesley Kimler, artist

- Jeff Kober, actor

- Leo Kottke, musician

- Wally Kurth, actor

- Joyce La Mers, author of light poetry

- Bud Luckey, Academy Award Nominee, famed Pixar animator for Toy Story 1–3

- Helen Lynch, actress

- T. J. Lynch, screenwriter

- Stan Lynde, creator of the comic strip Rick O'Shay, painter, and novelist

- Chase McBride, singer, musician, and visual artist

- Ralph McQuarrie, Academy Award-winning designer for Cocoon, the original Star Wars trilogy, the original Battlestar Galactica, and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial

- Marlene Morrow, former Playboy Playmate of the Month

- J. K. Ralston, Western painter

- Chan Romero, pioneer of rock and roll was born in Billings

- Rick Rydell, talk radio host

- Pete Simpson, musician and television performer in the 1950s in Billings; later member of the Wyoming House of Representatives; Republican nominee for governor of Wyoming in 1986.[163]

- Auggie Smith, comedian

- Carol Thurston, actress

- Chuck Tingle, two-time Hugo Award nominee

- David Yost, actor and producer, most notably the Blue Power Ranger on the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers

- Timothy DeLaGhetto, internet and television personality

Political edit

- James F. Battin, former Congressman from Montana

- Jim Battin, California State Senator

- Shane Bemis, Mayor of Gresham, Oregon

- John Bohlinger, former Lieutenant Governor of Montana

- Roy Brown, former Montana State Senator for District 25 and former gubernatorial candidate

- Conrad Burns, served in the U.S. Senate from 1988 to 2007

- Amanda Curtis, Montana State Representative for District 76 and U.S. Senate Democratic Candidate

- Hazel Hunkins Hallinan, women's rights activist and journalist

- Mike Mansfield, U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator for Montana, longest-serving Senate majority leader for Democratic Party, and U.S. Ambassador to Japan

- Jonathan McNiven, former Montana State Representative

- Ray Metcalfe, member of the Alaska House of Representatives

- Henry L. Myers, U.S. Senator and justice of the Supreme Court of Montana

- Denny Rehberg, former Congressman from Montana and former Lieutenant Governor of Montana

- Tom Stout, former Congressman from Montana and editorial writer for the Billings Gazette

- Burt L. Talcott, former Congressman from California

Tallest buildings edit

The tallest building in Billings and Montana as well as a five-state region is the First Interstate Center, which stands at 272 feet (83 m) and 20 floors above ground level.[164] Billings is also home to the world's tallest load-bearing brick building,[citation needed] the DoubleTree Tower, which stands 256 feet (78 m). With a floor count of 22 floors above ground level, the DoubleTree Tower is the tallest hotel in the city and state. It was the tallest from 1980 to 1985. The Wells Fargo Building, formerly the Norwest Bank Building, was the tallest building in Montana from 1977 until 1980.[165]

Sister cities edit

- Billings, Hessen, Germany

- Kumamoto, Kumamoto Japan

See also edit

- The USS Billings (LCS-15), a Freedom-class littoral combat ship of the United States Navy that is named after the city of Billings

References edit

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Billings, Montana

- ^ "ZIP Code Lookup". United States Postal Service. November 10, 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2007.

- ^ a b "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ a b c Big Sky Economic Development. "Big Sky Economic Development". Bigskyeda-edc.org. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Montana's Trailhead". Billings Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Best Places to Launch a Small Business 2009 – Billings, MT – FORTUNE Small Business". CNN. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Doyle, Shane; Doyle, Megkian (June 6, 2016). "30 Apsáalooke Place Names Along the Lewis & Clark Trail" (PDF). University of Oregon. p. 37. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "Cheyenne placenames".

- ^ "Billings MSA vs. Montana". Montana Regional Economic Analysis Project. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Lockwood CDP QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Quickfacts.census.gov. Archived from the original on June 16, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Our Changing Population: Yellowstone County, Montana". USAfacts. July 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Lutey, Tom (December 19, 2010). "Billings economy not an illusion". Missoulian.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Eastern part of state faring better economically". BillingsGazette.com. December 26, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Bakken: The Biggest Oil Discovery in U.S. History". Marketwire.com. April 15, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Bakken: The Biggest Oil Discovery in U.S. History | wallstreet:online". Wallstreet-online.de. April 15, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "A piece of the oil action". BillingsGazette.com. March 6, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Experts say Billings will benefit from energy boom". BillingsGazette.com. March 4, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "N. Dakota Bakken Oil Deposit Would Free USA of Foreign Oil Dependence – 2012 Pole Shift Witness". 2012poleshift.wetpaint.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Apsáalooke Place Names Database". Library @ Little Big Horn College. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ "Cheyenne placenames". Cheyenne Language. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ Cowell, A.; Taylor, A.; Brockie, T. (2016). "Gros Ventre ethnogeography and place names: A diachronic perspective". Anthropological Linguistics. 58 (2): 132–170. doi:10.1353/anl.2016.0025. S2CID 151520012.

- ^ "The Shores of an Ancient Sea..." (PDF). Montana Department of Transportation. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 24, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Pictograph Cave State Park". Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Pictograph Cave". National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Official Website of the Crow Tribe - Aps?alooke Nation Executive Branch". Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. "The Journals of Lewis and Clark, 1804–1806". Project Gutenburg. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ "Pompeys Pillar National Monument". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on March 16, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Historic Downtown Billings – Historical Overview". Yhpb.org. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Yellowstone County Towns, Train Stations & Post Offices". rootsweb. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Carkeek Cheney, Roberta (1983). Names on the Face of Montana. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. p. 5. ISBN 0-87842-150-5.

- ^ "Montana Place Names Companion". Montana Historical Society. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Billings: History". Advameg, Inc. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "John Liver Eating Johnston". Johnlivereatingjohnston.com. July 5, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Taylor". Billings.k12.mt.us. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Skyscraper Source Media Inc. "First Interstate Center". Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population by Counties and ... – United States. Bureau of the Census. May 17, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Population of Billings, Montana". Billings /: population.us. Retrieved March 11, 2019.

- ^ "Crowne Plaza, Billings, U.S.A". Billings /: Emporis.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Buildings of Billings". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "First Interstate Center, Billings, U.S.A". Billings /: Emporis.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Mount St. Helens – From the 1980 Eruption to 2000, Fact Sheet 036-00". pubs.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Yellowstone's Year Of Fire-1988". Yellowstone-bearman.com. August 20, 1988. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "the mission". Downtown Billings Alliance. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Gazette opinion: Another wave of downtown renaissance". Billings Gazette. July 17, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Preserve America Community". Preserveamerica.gov. March 13, 2009. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "City of Billings receives U.S. Green Building Council LEED Cities Grant". Billings Public Works. April 19, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "LEED for Cities Gold". City of Billings. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Gazette opinion: Public investment paves way for Shiloh businesses". Billings Gazette. September 3, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ Riesinger, Russ (May 19, 2021). "Bridge construction underway for new Billings Bypass project". KTVQ. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Project Overview". Montana Department of Transportation. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ "Transtech Center". Transtech Center. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Shiloh Road open end to end". BillingsGazette.com. November 13, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Magazine names Billings best small city for launching business". BillingsGazette.com. October 13, 2009. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Hiking & Backpacking". BighornMountains.Com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "The Pryor Mountains". The Pryors Coalition. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (June 16, 1996). "U.S. Budget Cuts Imperil Remote Town's Lifeline". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Crazy Mountains". Peakbagger.com. November 1, 2004. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Crystal Lake in the Big Snowy Mountains". Montanahikes.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "The Absaroka Mountain Range". greater-yellowstone.com. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ Peel, M. C., Finlayson, B. L., and McMahon, T. A.: Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 1633–1644, 2007.

- ^ Matt Brown, Associated Press Writers (June 20, 2010). "UPDATED: Tornado heavily damages MetraPark, Billings stores". Mtstandard.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access (Billings Logan Intl AP)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "WMO climate normals for BILLINGS/LOGAN INT'L ARPT MT 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access (Billings WTP)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ "Billings Brew Trail | visitbillings.com". Visitbillings.com.

- ^ Hoffman, Matt (April 8, 2016). "Students take first trip through halls of Medicine Crow Middle School". The Billings Gazette.

- ^ "BEA Statistical Areas". US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ "Personal Income for Billings". US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Lutey, Tom (December 18, 2011). "Billings ahead of almost everywhere: Agriculture, retail, energy, health care driving economy". Missoulian.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Home". Montana Department of Agriculture. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b "Agriculture". Billings Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Montana Brand Offices and Livestock Markets". Montana Department of Livestock. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Montana". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ "Automobile, Van, Light Truck Transportation". The Waggoners Trucking. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Rogers, Rob (March 31, 2022). "Local Coca Cola bottler breaks ground on new facility in Billings". Billings Gazette. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Facilities. "MetraPark Facilities | Arena, Expo Center, Montana Pavilion, The Grandstands". Metrapark.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Alberta Bair Theater". Archived from the original on August 19, 2012.

- ^ "Our History". Babcock Theater. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Daniel F. Ring, "Men of Energy and Snap: The Origins and Early Years of the Billings Public Library," Libraries & Culture (2001) 36#3 (2001) pp 397–412

- ^ Staff (April 28, 2007). "Gay Pride festival takes shap". Billings Gazette. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ Marino, Michael J. (July 1, 2022). "Nearly 4,000 Attend Billings Pride Event Downtown". Yellowstone County News. Vol. 45 (40 ed.). Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ^ "MontanaFair in Billings". Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ "ArtWalk Downtown Billings". Artwalkbillings.com. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ "31st Annual Strawberry Festival". Downtown Billings. 2022. Archived from the original on July 14, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Jan Falstad (April 29, 2012). "Thirst for craft beers prompts a boom in Billings brew pubs : Business". BillingsGazette.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Howard, Tom (February 1, 2013). "Trailhead Spirits: Distilling Montana's essence into memorable beverages". Billings Gazette.

- ^ "Billings Brew Trail | VisitBillings.com - Awe And Wonder - Visit Billings®". Visitbillings.com. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Parks & Trails". Billings Parks and Recreation. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "City Council Members". The City of Billings, Montana. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Pyburn, Evelyn (November 10, 2023). "Voters Defeat Recreation/Parks Bond in Landslide". Yellowstone County News. pp. 1, 3.

- ^ "About Yellowstone County, Montana". Yellowstone County, Montana. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "Courthouse Locations". U. S. District Court of Montana. Archived from the original on February 28, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Lagge, Mitch (October 1, 2019). "Billings City Council member says he's dropping NDO effort". KTVQ. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ Ferguson, Mike (August 12, 2014). "Council defeats NDO by 6–5 count". Billings Gazette. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "Billings City Council to look at non-discrimination ordinance again". KTVQ. September 10, 2019. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- ^ "Directory of Montana Schools". Montana Office of Public Instruction. March 13, 2024. pp. 303-305/319. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Yellowstone County, MT" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 13, 2024. - Text list

- ^ "About Billings Public Schools". Billings Public Schools. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "About Us". Blue Creek School. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "District Information". Elder Grove School. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ h"Grace Montessori Academy, a Billings Christian Montessori School".

- ^ Montana State University Billings. "History & Overview of MSU Billings". Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ Montana State University Billings. "Degrees, Programs, & Minors". Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ Montana State University Billings. "Full and Part Time Enrollment". Institutional Research. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "About the College". Montana State University Billings. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Pickett, Mary (May 25, 2012). "Regents approve new COT names". The Billings Gazette. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "City College Home". Montana State University Billings. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "Degrees and Programs". Montana State University Billings. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ "About RMC". Rocky Mountain College. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ "History of RMC". Rocky Mountain College. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ "Fall 2013 Student Body Profile" (PDF). Rocky Mountain College. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ "RMC – Majors". Rocky Mountain College. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ "General Information". Rocky Mountain College. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Monaco, Hailey (January 23, 2023). "Rocky Vista Montana College completes construction in Billings, looks forward to first class". KTVQ News. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ "Rocky Vista announces plans for college of veterinary medicine amid growing vet shortage". KTVQ News. January 12, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Miller, Norm (August 31, 2022). "Yellowstone Christian College Changes Name". Montana Southern Baptist Convention. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ "Jonathan McNiven | Yellowstone County News". Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "About." Yellowstone County News. p. 2. 2022 April 1.

- ^ "Who is the Best of Yellowstone County 2022? | Yellowstone County News". Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "About The Billings times. [volume] (Billings, Mont.) 1909-current". Chronicling America, United States Library of Congress. April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Lee DMS Group (April 24, 2009). "Magic – Billings' City Magazine Since 2003". Magiccitymagazine.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "About". Magic City Magazine. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ "Yellowstone Valley Woman". Yellowstone Valley Woman. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Billings Television Broadcasting Companies & Stations in Billings MT Yellow Pages by SuperPages". Superpages.com. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Radio Stations in Billings MT". Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "YCN Radio". Yellowstone County News. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ "Laurel Municipal Airport". Google Maps. January 1, 1970. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "City of Billings, MT – MET Transit". Ci.billings.mt.us. June 8, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Home". Greyhound.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2006. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Billings Parks & Rec – Trails". Prpl.info. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Bicycling's Top 50 | Bicycling Magazine". Bicycling.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Swords Park gets state, national honors". BillingsGazette.com. June 10, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Montana's Automatic Traffic Recorders" (PDF). Mdt.mt.gov. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ Billings, Mt (January 1, 1970). "billings montana". Google Maps. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ DOWL HKM. "Billings Area I-90 Corridor Planning Study". City of Billings. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "I90 Yellowstone River Project Billings". Montana Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "I 90: East Laurel - West Billings". Montana Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ "Project Description". Billings Bypass EIS. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ "Billings Bypass Status/Schedule". Montana Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Eggert, Amanda (February 21, 2024). "Long-distance rail route through southern Montana garners another nod from feds". Montana Free Press. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Mike Ferguson, "Billings' health care system a significant part of the local economy, study shows," Billings Gazette Dec. 14, 2014

- ^ "History". St. Vincent Healthcare. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Forte, Travia (January 9, 2024). "St. Vincents will Now Be Known As St. Vincent Regional Hospital". KULR-8. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ "2011 Facts". St. Vincent Healthcare. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Conlon, Casey (June 2, 2022). "St. Vincent Healthcare announces plans to build 'replacement' hospital in Billings". KULR-8. Retrieved March 28, 2024.