Romulus /ˈrɒmj[invalid input: 'ʉ']ləs/ is the mythical founder of the city of Rome and its first king. The legend of Romulus and his twin brother Remus /ˈriːməs/ is central to ancient Rome's foundation myth.[1]

The legend tells the tale of the twins' origins and youth and the events leading to Romulus' founding of Rome and reign as its first king. Ancient accounts differ, but agree on some basics. Most notable among these are the Rape of their mother Rhea Silvia by Mars; the infant twins being suckled by a she-wolf after being abandoned one the banks of the river Tiber; the contest of augurs; and the killing of Remus by his brother; the rape of the Sabine women; and Romulus' death and deification.

Other episodes include the palace intrigue between their grandfather Numitor and his brother, King Amulius prior to their birth; their adoption by shepherds; the overthrow of Amulius and restoration to the throne of Numitor; the contest of augurs; the establishment of the city and its institutions by Romulus; the city's betrayal by Tarpeia; the war with the Sabines and the Battle of the Lacus Curtius; the death of Romulus' Sabine co-ruler Titus Tatius; and the mysterious death and deification.

Overview edit

In the most commonly told account, Romulus and Remus are born in Alba Longa, one of the ancient Latin cities near the future site of Rome. Their mother is the daughter of the former king, Numitor, and they are descended, through her, from Greek and Latin nobility, they are seen as a threat to the current king, their maternal uncle, Amulius. He orders their deaths as infants, and they are abandoned in the wilderness to die on the banks of the Tiber River. They are saved by Tiberinus, the Father of the River and survive with the care of others. In the most well-known episode, the twins are suckled by a she-wolf.[2] Eventually, they are adopted by Faustulus, a shepherd, and raised tending flocks.

As adults, they depose Amulius, and restore their granfather Numitor to the throne. They set out to found their own city. but disagree about the hill upon which to build. Each claim the support of the gods by way of the auspices. Finally, their dispute escalates to the point where Remus is killed.[3]

Romulus founds the Rome and its institutions. These include the city's fortifications and army, it's legal, governmental and regilious institutions, it's class system and other Roman traditions. His city grows and becomes a magnet for immigration for people from other cities of all classes. In a series of wars, Rome defeats and conquers several of its neighbors. A lack of marriageable women sparks one of these conflicts, when Romans abduct a number of young, Sabine women. The fighting ends when the women themselves intervene and convince Romulus and the Sabine King Titus Tatius to make peace. The kings agree to become co-rulers of a single, combined kingdom and remain so until Tatius' death.

Romulus reigns for 36 years. But toward the end of his rule, he becomes more dictatorial and resentment in the people grows. One day, while outside the city, he is taken up into heaven and never seen again.[4] He is diefied as Quirinus.

The tale of Romulus and his twin brother are central to Rome and its history.[5] By the 4th century BC, the fundamentals of the story were standard fare, and by 269 BC the wolf and suckling twins appeared on one of the earliest, if not the earliest issues of Roman silver coinage. Rome's foundation story was evidently a matter of national pride. It featured in the earliest known history of Rome, and the tale was known to other Mediterranean peoples at the time. The image of the she-wolf suckling the divinely fathered twins became an iconic representation of the city and its founding legend, making Romulus and Remus preeminent among the feral children of ancient mythography.

Ancestry and Parentage edit

Through their mother, Romulus and Remus are descended from Aeneas the central figure in Aeneid of Virgil. Aeneas is a hero of Troy, who settled in Italy after the Trojans were defeated at the hands of the Greeks. He married Lavinia, the daughter of King Latinus. He succeeds to the throne and his descendants found Alba Longa and rule the city as its kings.

One of these descendants is King Numitor, whose daughter is the twins' mother. When Numitor is deposed by his brother Amulius, the new king forces his niece to become a vestal priestess and take their vow of chastity. Despite Amulius' efforts to prevent her from bearing any rivals to the throne, after a few years, she becomes pregnant and the twins are born.

The earliest unequivocal claim that Romulus is descended from Aeneas is a third-century epic poem by Gnaeus Naevius. Aeneas' role is featured in the works of Livy, Virgil, Dionysius, and Plutarch. The earliest reference to "Alba" occurs with that of Romulus in the 4th century BC.

Dionysius claims that the twins were born to a vestal named Ilia Silvia (sometimes called Rea). Proca, her grandfather had willed the throne to his son Numitor but he was later deposed by her uncle, Amulius. For fear of the threat that Numitor's heirs might pose, the king had Ilia's brother, Aegestus killed and blamed robbers. The truth about the crime was known by some, including Numitor, who feigned ignorance. Amulius then appointed Ilia to the Vestal priestesshood, where her vow of chastity would prevent her from producing any further male rivals. Despite this, she became pregnant a few years later, claiming to have been raped.

Livy claims that the twins were born to a vestal named Rea Silvia. Proca, her grandfather had willed the throne to his son Numitor but he was later deposed by her uncle, Amulius. She was forced to take the Vestal oath to prevent her from producing a rival to his rule. She became pregnant after taking her vows and claimed that she had been raped by Mars, the roman god of war. Livy speculates that the claim may have been made to conceal an earthly affair.

Plutarch adds details to the royal scandal behind the infant Romulus and Remus' abandonment in the wilderness. He quotes Diocles of peparethus and Pictor in writing that when Numitor and Amulius stood to inherit the throne, the twin's great grandfather gave his sons a choice between the throne and the treasures that had been brought back from Troy. Numitor chose the throne, but when he was overthrown, he ended up with neither. Along with the two names mentioned by Livy for the twins' mother, Plutarch tells us she may also have been named Ilia. The boys were the issue of Amulius himself, who raped his niece while wearing his armor. Upon the discovery of her pregnancy, her cousin Antho, the king's daughter convinced him to spare her life. He suggests that Faustulus may have been the name of the servant charged with the drown of the twins, as opposed to their adopted father. He names the site where the boys are brought back to dry land by Tibernius as Kermalus, formerly Germanus (from the latin word for twin).

In addition to the common tale, Plutarch relates one source wherein the twins' mother is Larentia a woman famous for her beauty and Hercules. She is forced to spend the night with the hero as his reward for winning a dice game with the keeper of his temple. In the morning, he throws her out and tells her to befriend the first man she meets. He is Tarrutius, a wealthy elderly childless bachelor. They sleep together, end up marrying and are together until his death.

Cassius Dio, in his 3rd century Roman History, relates that one source cited provides additional motives to Amulius for killing Aegestus and ordering the twins' deaths. An Oracle had foretold that the king would be killed at the hands of "children of Numitor". In this version, the twins are a product of an immaculate conception, and their mother's life is spared only because her cousin, the king's daughter convinces him not to put her to death for violating her vows.[6]

http://www.academia.edu/758835/Romulus_Aeneas_and_the_Cultural_Memory_of_the_Roman_Republic http://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/3387716/aeneas.pdf

Infancy and youth edit

The most common stories recount Amulius' order that the boys be drown in the river Tiber. Instead, they are left on the bank and rescued by forces both human and divine. In one iconic episode, the abandoned infants are nursed by a she-wolf before they are found and adopted by local herdsmen. They grow up tending flocks and become strong, well-regarded leaders of their community.

Dionysius edit

Citing Fabius, Cincius, Porcius Cato, and Piso, Dionysius recounts the most common tale. The king orders the twins to be tossed into the Tiber. When his servants arrived at the riverbank, high waters had made it impossible to reach the stream. They left the twin's basket in a pool of standing water on the site of the ficus Ruminalis. After the waters of the Tiber had carried the twins away, their basket is overturned by a rock and they are dumped into the mud. A she-wolf finds them there and nurses them in front of her lair (the Lupercal). Plutarch places the Lupercal as at the foot of Palantine hill along the road to the Roman chariot grounds and was the source of a natural spring.

The twins were discovered by unnamed herdsmen, and when they arrive, the she-wolf calmly retreats into the cave. Faustulus, the man in charge of the royal abattoir, happened upon the scene. He had heard the story of Ilia's twin birth and the king's order, but never let on that he suspected the foundlings were one and the same. He persuaded the shepherds to allow him to take the boys home, and brought them to his wife, who had just delivered a stillborn child. Later, quoting Fabius' account of the overthrow of Amulius, Plutarch claims that Faustulus had saved the basket in which the boys had been abandoned.

As they grew, the boys exhibited the graces and behavior of the royal-born. They passed their days living as herdsmen in the mountains, spending many nights in huts of reeds and sticks.

Livy edit

Livy claims that the twins were born to a vestal named Rea Silvia. She became pregnant after taking her vows and claimed that she had been raped by Mars, the roman god of war. Livy speculates that the claim may have been made to conceal an earthly affair. She was imprisoned by King Amulius and ordered the newborn twins to be cast into the River Tiber.

Later, In his account of the conflict with Amulius, Livy claims that Faustulus had always known that the boys had been abandoned by the order of the king and had hoped that they are of Royal blood, Histories I.5 </ref> He mentions without name sources that say that Larentia was in fact a prostitute who serviced Faustulus and the other shepherds and that the she-wolf tale arose from the slang word for her profession (lupa). The twins grew and became strong, smart youth who occasionally engaged in highway banditry, targeting thieves returning from their crimes laden with their ill-gotten goods.

Plutarch edit

Plutarch adds details to the royal scandal behind the infant Romulus and Remus' abandonment in the wilderness. He quotes Diocles of peparethus and Pictor. Along with the two names mentioned by Livy for the twins' mother, Plutarch tells us she may also have been named Ilia. The boys were the issue of Amulius himself, who raped his niece while wearing his armor. Upon the discovery of her pregnancy, her cousin Antho, the king's daughter convinced him to spare her life. He suggests that Faustulus may have been the name of the servant charged with the drown of the twins, as opposed to their adopted father. He names the site where the boys are brought back to dry land by Tibernius as Kermalus, formerly Germanus (from the latin word for twin).

In addition to the common tale, Plutarch relates a version where the twins' mother is Larentia a woman famous for her beauty and Hercules. She is forced to spend the night with the hero as his reward for winning a dice game with the keeper of his temple. In the morning, he throws her out and tells her to befriend the first man she meets. He is Tarrutius, a wealthy elderly childless bachelor. They sleep together, end up marrying and are together until his death. Faustulus is, in this account, in the employ of Amulius. The basket in which they were abandoned bore a bronze inscription of their names and was kept by Faustulus, however, the inscription has worn off, but it was hoped that it might be used to determine their true parents.

Numitor and others possibly know the secret of the twins origin and Numitor has them educated in Gabii. Romulus was the more dominant of the two. They were defiant toward the authorities and instead of being highwaymen preying on other thieves, here they are portrayed as vigilante protectors of their neighbors. In a story from Gaius Acilius, on one occasion, the twins had lost their flock and they set out after them naked so their sweat won't slow them down. Because they were guided by Faunus, the god of nature, this inspired the later festivals

Plutarch relates also an alternate, "non-fantastical" version of Romulus and Remus' birth, survive and youth. In this version, Numitor managed to switch the twins at birth with two other infants. They were raised by Faustulus, who was descended from the first Greek colonists in Latium. He was the caretaker for Amulius' holdings around Palatine hill. He was persuaded to care for the twins by his brother Faustinus, who tended the kings herds on nearby Aventine hill.

Their adopted mother was Faustulus' wife Laurentia, a former prostitute. According to Plutarch, lupa(latin for "wolf") was a common term for members of her profession and this gave rise to the she-wolf legend. The twins receive a proper education in the city of Gabii.

Cassius Dio claims that the twins were not to be drowned, but merely left exposed by the river. Faustulus himself is given the task, but instead he brings them home to his wife, who had recently delivered a stillborn.

Overthrow of Amulius edit

Unbeknownst to any of the three, Romulus and Remus are in the employ of their uncle King Amulius, who had usurped their Grandfather's throne and ordered their deaths. They become involved in a dispute with which ends with Remus' capture and delivery to Alba Longa face justice. When he meets Numitor, the truth about is true identity is revealed. Romulus leads a group of supporters to the city to free his brother. Once Romulus also knows their origins, the three combine forces to overthrow and kill Amulius and restore Numitor to the throne. They then set forth to found a great city of their own.

Dionysius edit

According to Fabius, when the twins were 18, they became embroiled in a violent disputes with some of Numitor's herdsmen. In retaliation, Remus was lured into an ambush and capture while Romulus was elsewhere. In Aelius Tubero's version, the twins were taking part in the festivities of the Lupercalia, requiring them to run naked through the village when Remus, defenseless as he was, was taken prisoner by Numitor's armed men.

After rounding up the toughest herdsmen to help him free Remus, Romulus rashly set out for Alba Longa. To avoid tragedy, Faustulus intercepted him and revealed the truth about the twins' parentage. With the discovery that Numitor was family, Romulus sets his sights on Amulius, instead. He and the rest of his village set out in small groups toward the city so that their arrival will go unnoticed by the guards. Meanwhile, after being turned over to Numitor to determine his punishment, Remus was told of his origins by the former king and eagerly joins with him in their own effort to topple Amulius. When Romulus joined them at Numitor's home, the three of them began to plan their next move.

Back home, Faustulus had begun to worry about how the twins' claims will be heard in Alba. He decides to bolster them by bringing the basket in which they were abandoned to the city. He's stopped by suspicious guards at the gates and he and the basket are seen by none-other-than the servant who had taken them to the river those many years before. Under the questioning of the king, and after the king's insincere offers of benevolence toward his nephews, Faustulus, trying to protect Romulus and Remus, and escape the king's clutches, claimed he had been bringing the basket to the imprisoned Ilia at the twins request and that they were at the moment tending their flocks in the mountains.

Amulius sent Faustulus and his men to find the boys. He then tried to trick Numitor into coming to the palace so that the former king could be kept under guard until the situation had been dealt with. Unfortunately for the king, the man he sent to lure Numitor into his clutches instead revealed everything that had happened at the palace.

The twins and their grandfather led their joint supporters to the palace, killed Amulius, and took control of the city.

Livy edit

On their way to celebrate the Lupercalia, the twins were ambushed by some of the thieves they had formerly robbed. After a struggle, Remus was captured. The theives brought him before King Amulius and accused him of trespassing and committing crimes on Numitor's land. He was handed over to the former king, his grandfather--unbeknownst to either at the time--for punishment.

Livy states that when Faustulus had found the infant twins in the wild, he knew that they had been cast out on the order of the King. He had long suspected that they were royal-born. Now, with Remus in the clutches of the same King who had been behind their childhood ordeal, he feared for him and told Romulus the truth. Meanwhile, Numitor, encountering for the first time his grandson, whom he had thought long dead, apparently looked favorably upon his royal demeanor and physicality. He puts two and two together and realized the truth of who Remus and his twin brother Romulus are. the three join forces against their kin, Alumius.

Through subterfuge and force, Numitor, Romulus and Remus kill their brother and uncle, avenging the usuper's crimes against each. An assembly was called. Numitor revealed the truth about his grandchildren and announced the death of Alumius, claiming he had given the order to kill him. To help boost their grandfather's effort to regain his throne, the twins marched their men into the center of the assembly and proclaimed him king. The people followed their lead and Numitor was once again king of the Alban kingdom. Inspired, Romulus and Remus decided to found their own city, which will dwarf their neighbors.

Plutarch edit

A dispute between herdsmen loyal to Numitor and Amulius is at the heart of this version. The twins sided with Amulius. Remus was captured when Romulus was elsewhere. When Faustulus learned that Remus has been taken to Numitor, he went to Alba with the basket in which the infant twins were abandoned. I bore a copper plate with an engraving that had long been effaced. He was stopped by the city guards at the gate. The servant charged with abandoning the twins happened to be present and saw the basket, immediately going to inform the king. When brought0 before Amulius, Faustulus tries to fool the king by telling him the twins were alive elsewhere and the basket was being brought to their mother Ilia.

Citing Fabius and Diocles, Plutarch writes that Amulius sent a man close to Numitor to ask if he had any word that the twins were alive. However, when he arrives, he sees Remus and Numitor together and warns them. They incited the people against the king just as Romulus had arrived with an army of supporters to attack the city. The king is promptly overwhelmed and killed.

Plutarch continues the same alternate version of the twins' parentage and youth. After the boys had returned home from their studies in Gabii, Numitor has the twins attack his own herdsmen and drive off his own cattle to contrive a complaint against his brother. To placate him, Amulius ordered not only the twins to be brought to the palace for trial, but all the others who were present, as well. This is exactly what Numitor had hoped for. When Romulus and Remus arrived in Alba, their grandfather revealed their true identity and he, the twins and the other herdsmen joined forces to attack Amulius, apparently killing him.

Fratricide edit

Romulus and Remus set forth from Alba with a group of followers to found a new city. When they arrive in the area of the Rome's seven hills, they cannot agree upon which to build. Romulus prefers the Palatine and Remus the Aventine. They look to the gods to settle the matter by sending them an omen. Both twins see bird omens. Remus sees his before Romulus, but Romulus sees more of them. The conflict escalates and Remus is killed.

Dionysius edit

Outwardly, the twins both acknowledged the other's claim to having won. Remus by seeing the vultures first, and Romulus by seeing more of them. Privately, however, neither was willing to give in. An armed battle broke out between their followers resulting in deaths among both. Faustulus was so distraught over his inability to end the strife between his adopted sons that he threw himself into the middle of the fighting and was killed. Remus also falls. Romulus is devastated at his personal losses as well as the many suffered by the twins' followers. Only after the intervention of Laurentia is he able to return to the job of founding the city.

Other sources who are unnamed by Plutarch claimed that despite his anger over Romulus' conduct during the contest of the augury, Remus conceded and the construction of the city began on Palatine Hill. Out of resentment, he derided the city's newly-built walls and demonstrated their ineffectiveness by leaping over them, saying that an enemy of Romulus could do the same. In response, Celer, the job's foreman killed him on the spot with a blow to the head and implies that Remus himself had become his brother's enemy.

Livy edit

Livy claims that the twins began to argue almost immediately after starting out on their undertaking. According to Livy, both Romulus and Remus wanted to be the king of their new city, which he attributed partly to their discovery that they are royalty. That and the fact that there was no older brother between them to whom the younger could demur, made dispute resolution difficult. Finally, they agreed to allow the gods to settle the matter by way of an omen.

Each twin sat on their respective hill and watched. First, Remus saw six birds and claimed the gods had chosen him. Then Romulus saw twelve birds and claimed that he was the chosen one. Livy's version has the twins fighting and Remus dying from a blow by Romulus. He also sites the "more common" account, wherein Romulus leaped over Romulus' wall and was killed by Romulus in a fit of rage. Afterwards, he declares: "Sic deinde, quicumque alius transiliet moenia mea" ("So is it with anyone who leaps over my walls").

Plutarch edit

Plutarch claims that many slaves and fugitives were already following the twins when they set forth and were motivated by the Alban's unwillingness to allow their cohorts to remain. He adds that some sources indicate that Romulus lied about the 12 birds he saw during the contest with Remus. Remus is killed either by his brother, or Celer, Romulus' man, who then fled to Tuscany with so much haste that his name became the Latin word for speed. Also killed was Faustulus' brother Pleistinus.

Dio edit

In a fragment from his History, Dio claims simply that the conflict between the two boys boiled down to who would be in charge. And that Remus' death was the origin of the Roman army's tradition of executing anyone who entered a camp by any means other than the established paths (as opposed to crossing the defensive trenches dug around them)

Founding of Rome edit

Romulus founded the city and began undertaking the establishment of its institutions, practices, and traditions. He first focuses on defending the city , but by building fortifications and by encouraging growth through immigration. He forms an army. He establishes the city as a monarchy, but one wherein the governed would have a say in who wears the crown through political institutions such as the senate and the public assemblies. He lays down what will become the official religious practices, including the proper manner of sacrifice and the importance of the augury.

Dionysius edit

Before construction on the city began Romulus made sacrifices and received good omens, and he then ordered the populace to ritually atone for their guilt. The city's fortifications were first and then housing for the populace. He assembles the people and gives them the choice as to what type of government they want. After his address, which extols Bravery abroad war and moderation at home, and in which Romulus Denies any need to remain in power, the people decide to remain a kingdom and ask him to remain its king. Before accepting he looks for a sign of the approval of the gods. He prays, and witnesses an auspicious lightning bolt, after which he declares that no king shall take the throne without receiving approval from the gods.

Establishment of classes edit

He divides Rome into 3 tribes, each selected a Tribune in charge of each. Each tribe was divided into 10 Curia, and each of those into smaller units. He divided the kingdoms land holdings between them. Plutarch suggests that Athenian institutions were the inspiration for Romulus' creation of the Patrician class from the wealthy and virtuous. Other sources cited claim All others Roman's formed the Plebeian class. The Patricians were put in charge of religious, legal and civil institutions, while the Plebs were to be farmers, herders and tradesmen. Each curiae was responsible for provided soldiers in the event of war.

Clientela and Celeres edit

To maintain order, every pleb had the right to chose a Patrician in a system of patronage (clientela). All patrons (patronus) were required to protect the rights and interests of those plebs (cliens) beneath them. In return all plebs were required to support his patron in his endeavors and assist him when needed. It was illegal for either party to testify against one another or otherwise act against the interests of the other. Romulus then proceeded to establish the senate. Another act that Dionysius attributes to Greek influence. He selected 300 of the strongest and fittest among the nobles to become his personal bodyguard and messengers. The celeres were so-named either for their quickness, or, according to Valerius Antias, for their commander. These were the first Roman cavalry and were instrument in many Roman victories.

Separation of powers edit

Romulus then delimited the various powers of the institutions he had created. The Roman king was made the ultimate authority in all religious and legal matters. He would personally hear the cases of "the greatest crimes" but after reaching a decision, his opinion would be subject to approval by the people. He would be the commander in chief of the military in wartime.

The senate would have the power to decide any matter or issue brought to them by the king with a binding vote (attributed by Dionysius to the Lacedaemonians. The popular assemblies had the power to elect magistrates, pass laws and declare war at the king's discretion.

Growth of Rome edit

Romulus passed laws meant to encourage child-rearing. He welcomed free men of any background to settle in the new city with promises of citizenship and an offer of protection from those from home who might be pursuing them. Immigrants flocked to Rome as a result. Rome would also benefit from their practice of sending colonists to newly-conquered cities and allowing the subjugated to carry on as they had before. More common in the Greek world was to treat those they defeated harshly. Rome grew 10 during Romulus' reign.

Religious institutions edit

In an extensive exploration of the various, lurid traditions of the day, Dionysius effusively praises the manner in which Romulus' organized and established Rome's religious customs and practices. He attributes to the king everything from the founding of temples, to defining the sphere of individual gods, their festivals and the blessings they would each bestow. Among the Greek and native traditions, he kept only those he deemed worthy and rejected any that were too unseemly or otherwise unfit for Roman society.

According to Terentius Varro, Romulus appointed a large number of Roman men and women to religious office during his reign. He also allowed the various curia to select their own. He adopted the greek practice of appointing children to participate in the city's ceremonies. He established an office of augury, who would ensure the approval of the gods during all worship undertaken. Each curia was required to sacrifice and give offerings in a way so specified. He established budgets for religious practice in the city.

Legal institutions edit

Again, Dionysius thorough describes the laws of other nations before contrasting the approach of Romulus and lauding his work. The Roman law governing marriage is, according to his Antiquities an elegant yet simple improvement over that of other nations, most of which he harshly derides. By declaring that wives would share equally in the possessions and conduct of their husband, Romulus promoted virtue in the former and deterred mistreatment by the latter. Wives could inherit upon their husband's birth. A wife's adultery was a serious crime, however, drunkenness could be a mitigating factor in determining the appropriate punishment. Because of his laws, Dionysius claims, not a single Roman couple divorced for the next 5 centuries. His laws governing parental rights, in particular those that allow fathers to maintain power over their adult children were an improvement over those of others.

Under the laws of Romulus, native-born free Roman's were limited to two forms of employment: farming and the army. All other occupations were filled by slaves or non-roman labor.

Romulus used the trappings of his office, to encourage compliance with the law. His court was imposing and filled with loyal soldiers and he was always accompanied by the 12 lictors appointed to be his attendants.

Livy edit

Upon the death of his Remus, Romulus becomes the sole king of the new city. Romulus first fortified the city and then offered sacrifices to the Gods and Hercules. He notes the care with which he conducts the rituals. He gives a lengthy telling of the tale of Evander, the Greek who brought writing and scholarship to Italy and built an alter to Hercules' after he slew the Cacus on Palatine Hill in the time before Romulus. After creating a code of laws, Romulus adopted the trappings of a king, including a purple robe and throne borrowed from the Etruscans in order to better gain respect among the commoners.

Chiefly in this effort, He appointed 12 lictors to be his attendants. Livy supports the sources that say he chose the number "12" from the bird omen by which he became king. He also refers to a different account which attributes his choice to the Etruscan tradition of selecting their kings by a vote of the 12 lictors representing each of the 12 Etruscan states. He built new structures to enlarge the city and to grow the city's population, he allowed anyone, no matter what past or class to come. He put this new rabble to work for his own political purposes, but declaring an area In order to strengthen his new city, Romulus built improvements in the city.constructed new buildings and dedicates a temple to Asylaeus, god of fugitives and exiles, to welcome immigrants of all classes from Rome's neighbor. Once the population had increased, he named 100 Paters (Patriarchs) as the first senators. The patrician class is descended from the families of these men.

Dio edit

Dio provides a description of the king:

"Romulus had a crown and a sceptre with an eagle on the top and a white cloak reaching to the feet and striped with purple breadths from the shoulders to the feet . . . and a scarlet shoe."[6]

The rape of the Sabine Women edit

Rome has grown until it's size and strength rivals the other cities in the region. Concerns arise, however, over the inadequate number of marriageable women. Romulus appeals to their neighbors to allow intermarrying. Owing to Rome's lack of pedigree and "rough" population of immigrants and outcasts, the established families in the area are resistant to joining with the city's men. This lack of filial connections also worries the Romans, surrounded as they are with other, sometimes hostile foreign countries.

Romulus sees an answer to both problems. He announces a major festival to be held in their new city and invites all to come and participate. Many outsiders attend, including a large number from the community of Sabinia. At a pre-arranged moment, the men of Rome begin abducting the young women that have come to the festival, spiriting them away to the horror of their families.

Dionysius edit

According to Gnaeus Gellius, in Romulus' fourth year in power, the recently founded city of Rome, its population swollen with immigrants found itself surrounded by unfriendly neighbors and short of marriageable women. Romulus sought to solve both problems through intermarrying with the other cities in the region, but he was rebuffed. His solution having been approved by his Grandfather, received the auspices of the gods, and the support of the senate began with the announcement of a spectacular festival and competitions to honor the god Neptune, and to which all of Rome's neighbors were welcome. They came from far and wide, sometimes entire families, to attend and participate.

On the king's signal, Romans began abducting the young women in attendance much to the shock and horror of their guests. Later, the women are brought before him where he assures them that he and the other men of Rome intend to honorably marry them and that they won't be sexually exploited in anyway. This eases their fears.

Plutarch edit

The abduction took place 4 months after the city was founded. Plutarch doubts sources that claimed that Romulus' true motive in abducting the women was to start a war with Rome's neighbors. He does, however support another motive, Romulus' desire to bring better order to the disorderly people of Rome through marriages. Only the Sabines were invited. As is often the case with his account, Plutarch adds significant details. He lists the number of women abducted from the different sources: 30, 527 or 683. Some sources claim that Hersilia was one of the women taken and the only married woman. Romulus had two children by her: a daughter Prima and a son Aollius according to Zenodotus, but Plutarch discredits this claim. One source relays that "Talassius" is the signal that Romulus gave to start the abductions, and the Romans use that term for nuptial.

Wars and the aftermath edit

Rome is invaded in turn by the cities of Caenina, Crustumerium, and Antemnae when they are unable to win the return of their abducted women. Each is defeated and each comes under Roman control. Finally, Titus Tatius, king of the Sabines marches forth with his own army. The army of the Sabines proves a much more worthy opponent than the other three cities. They manage to capture Rome's citadel by guile, instead of force. The two nations engage in an epic battle that ends only when the Sabine women intervene and convince them to make peace. Afterwards, the two kingdoms become one with Tatius and Romulus ruling as joint kings.

Caenina, Crusumerium, and Antemnae edit

Dionysius edit

The cities of Caenina, Crustumerium, and Antemnae petition Tatius, king of the Sabines to lead a joint attack in response to the kidnappings. Their goal was stymied by Rome's own diplomatic efforts and the other three cities eventually concluded that Tatius was delaying any action on purpose. They decide to attack Rome without the Sabines and their armies are defeated and their cities captured each in turn.

Livy edit

When the parents of the women return home according to Livy, they acted like they were in mourning and made their anguish and upset public. Everyone joined in their protests to King Tatius. Because he was so admired, delegations were sent from the other cities to demand he act. However, anger grew when they began to think that Tatius was dragging his heels. Acra, the king of Caenina decided to invade Roman territory on his own. Romulus marched forth and found them in small, disorganized groups, and after a short battle, their army was routed and Acra was chased down and killed by the pursuing Roman army. They continued on to capture Caenina.

When Romulus returned with his spoils, he dedicated a temple to Jupiter and made an offering of them. He declared that such an offering would be made by any future kings upon their killing of an enemy king or general. It would be the first temple built in Rome. Livy notes that afterwards, the offering was made only two more times. Meanwhile, the army of Antemnae invades and are again quickly routed when they are ambushed and that city also falls to Rome. On behalf of the abductees, Romulus' wife, Hersilia convinces him to grant the fathers of the women citizenship. After capturing the Crustumerium, Many of the family members of the women migrate to Rome, and Romans colonize the other cities.

Plutarch edit

In this version, the Sabines sent a delegation to Rome to ask for the women's return and an alliance and an agreement to marry with Roman men. Romulus rejected it and the cities make long preparations for war. Although not victimized by the abductions, Caenina was alarmed enough at Rome's brazen crime that they decided to invade on their own. In this version, the enemy king was not chased down after routing, but was killed by Romulus after agreeing to individual combat with Romulus, instead of a battle. Plutarch writes that Fidenae invaded along with the other two cities mentioned by Livy, instead of after the war with the Sabines was over. Rome defeated the combined forces in a single battle and conquered their cities.[7]

War with the Sabines edit

The war between Rome and the Sabines features three significant episodes: The betrayal of the Roman citadel by Tarpeia, the Battle of Lacus Curtius, and the intervention of the Sabine women to end the war. Tatius gains access to the Roman citadel with the assistance of the commander's daughter, either through her deliberate betrayal of her country or by trickery. Operating from the stronghold, the Roman's efforts to defeat them as easily as the other cities is stymied. When the armies meet, they fight an epic battle with multiple turns of fortune and the upper hand lost and won by both. The battle and the war finally end when the abductees confront the armies and persuade them to accept each other as now joined together by way of their new families.

Caenina, Crusumerium, and Antemnae edit

Dionysius edit

The cities of Caenina, Crustumerium, and Antemnae petition Tatius, king of the Sabines to lead a joint attack in response to the kidnappings. Their goal was stymied by Rome's own diplomatic efforts and the other three cities eventually concluded that Tatius was delaying any action on purpose. They decide to attack Rome without the Sabines and their armies are defeated and their cities captured each in turn.

Livy edit

When the parents of the women return home according to Livy, they acted like they were in mourning and made their anguish and upset public. Everyone joined in their protests to King Tatius. Because he was so admired, delegations were sent from the other cities to demand he act. However, anger grew when they began to think that Tatius was dragging his heels. Acra, the king of Caenina decided to invade Roman territory on his own. Romulus marched forth and found them in small, disorganized groups, and after a short battle, their army was routed and Acra was chased down and killed by the pursuing Roman army. They continued on to capture Caenina.

When Romulus returned with his spoils, he dedicated a temple to Jupiter and made an offering of them. He declared that such an offering would be made by any future kings upon their killing of an enemy king or general. It would be the first temple built in Rome. Livy notes that afterwards, the offering was made only two more times. Meanwhile, the army of Antemnae invades and are again quickly routed when they are ambushed and that city also falls to Rome. On behalf of the abductees, Romulus' wife, Hersilia convinces him to grant the fathers of the women citizenship. After capturing the Crustumerium, Many of the family members of the women migrate to Rome, and Romans colonize the other cities.

Plutarch edit

In this version, the Sabines sent a delegation to Rome to ask for the women's return and an alliance and an agreement to marry with Roman men. Romulus rejected it and the cities make long preparations for war. Although not victimized by the abductions, Caenina was alarmed enough at Rome's brazen crime that they decided to invade on their own. In this version, the enemy king was not chased down after routing, but was killed by Romulus after agreeing to individual combat with Romulus, instead of a battle. Plutarch writes that Fidenae invaded along with the other two cities mentioned by Livy, instead of after the war with the Sabines was over. Rome defeated the combined forces in a single battle and conquered their cities.[8]

War with the Sabines edit

The war between Rome and the Sabines features three significant episodes: The betrayal of the Roman citadel by Tarpeia, the Battle of Lacus Curtius, and the intervention of the Sabine women to end the war. Tatius gains access to the Roman citadel with the assistance of the commander's daughter, either through her deliberate betrayal of her country or by trickery. Operating from the stronghold, the Roman's efforts to defeat them as easily as the other cities is stymied. When the armies meet, they fight an epic battle with multiple turns of fortune and the upper hand lost and won by both. The battle and the war finally end when the abductees confront the armies and persuade them to accept each other as now joined together by way of their new families.

Tarpeia edit

Dyonisus reports that Sabinia spent a year raising an army and that Rome spent this time improving its defenses and being reinforced with Albans sent by Numitor and mercenaries under the command of the king's friend and renowned commander Lucumo. After a final effort to resolve the matter peacefully, the Sabine army marched forth. According to Fabius and Cincius, Tatius tricked the daughter of the commander of the city's walled citadel to open the gates to his men by offering her what she thinks will be the gold bracelets they wear on their left arms, instead they crushed her to death when they heaped their shields on top of her as her reward. Lucius Piso claimed that she was motivated not by greed, but a plan to trick the Sabines and that she was killed only after they came to suspect her of treachery.

According to Livy, the Sabines were, unlike the other cities, cunning and calculating when it came to war. Tatius tricked the daughter of the commander of the city's walled citadel to open the gates to his men by offering her what she thinks will be the gold bracelets they wear on their left arms, instead they crushed her to death when they heaped their shields on top of her as her reward. Livy reports that other sources claim that she was killed only after the Sabines came to suspect her of treachery.

Battle of the Lacus Curtius edit

Dionysius edit

Romulus and Lucumo were successfully attacking from both wings, but were forced to disengage when the center of the Roman line broke in order to stop the Sabines' advance under their general Mettius Curtius. After being turned back, the Sabines orderly retreat and Mettius and Romulus engage one another directly until wounded, Mettius falls back until a marshy lake prevents any further escape. He plunges into it and stymies his enemy's pursuit. Once Romulus has returned to the remaining Sabine forces and left him behind, the Sabine general eventually pulls himself out of the mire and safely returns to his camp. marched forth, on the verge of victory.

When Romulus was struck in the head with a stone, the tide reversed as the Romans lost heart without their commander. The army was in full-flight after a javelin felled Lucumo. Romulus recovered, and with the support of fresh reserves from within the city, the Romans regained the upper hand and the lines moved back against the Sabines. With sunset at hand, the Sabines made and arduous retreat to the citadel and the Romans broke off their pursuit.

Livy edit

When the Roman army assembled at the foot of the hill beneath the citadel, the Sabines refused to emerge and engage them. Finally, in spite of their lack of the high ground, the frustrated Roman army attacked. Initially inspired by the heroics of their general Hostus Hostilius on the front line, the Romans line broke when he fell, and they were pushed back across the low ground between the Capitoline and Palatine hills. The Sabines marched forth, on the verge of victory. Romulus makes a pledge to Jupiter that if he will hold off the Sabine charge and restore the Roman's courage, he will build a new temple of Jupiter the Steadfast on the site. With a cry, Romulus led his army into the Sabines and routed them. The Sabine general Mettius was tossed in a swamp by his horse after it bolted.

The After the Sabines regrouped, the battle continued in the area between the two hills, but the Roman army had by then gained the upper hand. Suddenly, the abducted Sabine daughters rushed onto the battlefield and put themselves between the two armies.

Plutarch edit

In the account of the Battle of the Lacas Curtius, Plutarch again provides many details, but the basic account is the same as Livy. Here, the Roman line broke not because of Hostilius' death, but because Romulus was struck by a stone to the head. He rallied the men after recovering. When the women intervene to stop the fighting, some of them have children in their arms. The women not only end the battle, but bring food and water, care for the injured and introduce their husbands to their fathers.

Union with the Sabines edit

Dionysius edit

After the battle, both commanders were left without any ideas, when the women at the center of the dispute took matter into their own hands. Led by the noble Hersilia, the women got permission from the senate to address the army of their former homeland, and, some in funerary attire, some carrying their children with them, they convinced Tatius to seek peace.

After a ceasefire, the nations agreed to become a single kingdom under the joint rule of Romulus and Tatius. The city was expanded and its institutions were adjusted to accommodate the new increase in population and to demonstrate their mutual good will. The joint kingship lasted for four years until the death of Tatius. During this time they conquered the Camerini and made their city a Roman colony.

Livy edit

Many of the abducted Sabine women have formed relationships with Roman men; and now they intervene to beg for unity between Sabines and Romans. A truce is made, then peace. The Romans base themselves on the Palatine and the Sabines on the Quirinal, with Romulus and Tatius as joint kings and the Comitium as the common centre of government and culture. 100 Sabine elders and clan leaders join the Senate. The Sabines adopt the Roman calendar, and the Romans adopt the armour and oblong shield of the Sabines. The legions are doubled in size.

Tatius and Later Rule edit

The combined population are under the harmonious rule of Tatius and Romulus until a crime against the citizens of another city leads to Tatius' killing. Romulus continues to rule both nations alone. He wars against other neighbors and is victorious. However, his rule becomes more dictatorial and his popularity fades among the noble, though not among the commoners or the army.

Dionysius edit

The two people are merged under a joint throne with Rome as the capital. The Sabines and Romans alike were then declared Quirites, from the Sabine city of Cures. To honor the Sabine women, when Romulus divided the city into 30 local councils, he named them after the women. He also recruits three new units of knights and called them Ramnenses Tatiensis (from the two kings names).

Some of Tatius' friends victimized some Laurentii and when the city sent ambassadors to demand justice, Tatius would not allow Romulus hand over the perpetrators over to them. A group of Sabines waylay the ambassadors as they sleep on the way home. Some escape and when word gets back to Rome, Romulus promptly turns the men respsonsible--including one of Tatius' family members--over to a new group of ambassadors. Tatius follows the group out of the city and frees the accused men by force. Later, while both kings are participating in a sacrifice in Lavinium he is killed in retribution.

Dionysius tells the account of Licinius Macer wherein Tacitus was killed when he went alone to try and convince the victims in Lavinium to forgive the crimes committed. When they discovered he had not brought the men responsible with him, as the senate and Romulus had ordered, an angry mob stones him to death.

Livy edit

Fearing the growing threat Rome posed, the nearby Etruscan city of Fidenae invaded and began pillaging the land between the two cities. Romulus ambushed them and pursued them back to their city, managing to follow them through their gates before they can be closed. This draws in the people of Veii, also from Etruria and also fearful of Rome's rising power. They likewise invade Rome and engage in looting before withdrawing. When the Roman army is denied an engagement, they set up camp and are suddenly set upon by the Veientes. Despite there utter lack of preparation, the strength of the veteran Roman troops prevails. Declining to besiege the city, Romulus laid waste to their fields in repayment for their crimes. They concluded a 100-year peace treaty with Veii in exchange for some of their land.

Plutarch edit

According to Plutarch, the two kings were in full agreement on all except one: the royal response to the crime committed by members of Tatius' relatives against the Laurentian ambassadors. Some of Tatius' relatives killed a group of ambassadors from Laurentium when their attempt to rob them went wrong. For the only time during their reign, the kings disagreed. Romulus wanted to punish the men with death promptly, and Tatius did not. Later, while sacrificing with Romulus in Lativium, friends of the ambassadors attacked and killed Tatius, but spared Romulus, praising his sense of fairness.

Tatius was given a royal burial, however Plutarch reports that there are no efforts to punish his killers. He cites one source that claims that the assassins were brought by Laurentium authorities to Romulus but he declined to punish them. Rome was later visited by a series of plagues, and when it spread to Laurentuim, it was thought to be a result of the unjust treatment in the death of Tatius and the ambassadors. Both cities brought to justice the parties involved in the two attacks, and Romulus performed rights to purify the cities.

Rome was weakened by the plague and this prompted Camerium to invade. In one version of the war with Fidenae, Romulus did not raze the city, but instead declared it a colony and sent 2500 Romans to live there.

Death of Romulus edit

While in Capra reviewing troops, a storm arose and Romulus was swept up in a whirlwind, never to be seen again. When the nobles who were nearest him at the time report this to the public, there is widespread acceptance of the account. The people were lost in their sorrows until a few, and then all of them declared "deum deo natum, regem parentemque urbis Romanae salvere universi Romulum iubent" "Romulus, you are descend from the gods, our king, the father of our city and the defender of all Romans!"

Livy goes on to say that he believes that despite the outpour of emotion by the public, there were those who even at the time suspected that Romulus had in fact been murdered by a group of patricians who then dismembered his body and disposed of the parts. Rumors of such spread a growing resentment against the nobles. He tells us that a well-esteemed Roman named Proculus Julius came forward and reported that Romulus had appeared before him at dawn and told him that he the gods willed that Rome be the capital of the world. They should keep their armies strong and that Roman power and arms will never be overcome. He then ascended into the sky as a god. On a final note, Livy expresses his surprise that the anger on behalf of the commoners and the army was so easily laid to rest by hearing that he was now an immortal.

Plutarch edit

Plutarch recounts several versions of the death. In one, he died peacefully after a long illness. In another, he committed suicide by poison. He recounts two versions wherein he died violently, either by assassins who smothered him at home during the night, or by senators who lured him to the Temple of Vulcan where they killed and dismembered him and each disposed of a small part of his corpse, hidden in their robes. He details the motivations of the senate, saying there was anger toward his demeanor toward them and disregard toward their legal sovereignty in diplomacy and legal proceedings.

In the version cited by Livy, the gods themselves were suggested to have intervened. He retells one variant wherein the emotions of the public were assuaged not only by the oath of Proculus Julius to have seen the deified king, but also by an apparently divine force that quieted the anger and suspicions toward the nobles. It descended upon the city and the Romans accepted and worshiped Romulus as Quirinus. Romulus was 54 years old when he disappeared.

Other sources edit

Fabius' history provided a basis for the early books of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita, which he wrote in Latin, and for several Greek-language histories of Rome, including Dionysius of Halicarnassus's Roman Antiquities, written during the late 1st century BC, and Plutarch's early 2nd century Life of Romulus.[9][10] A Roman text of the late Imperial era, Origo gentis Romanae (The origin of the Roman people) is dedicated to the many "more or less bizarre", often contradictory variants of Rome's foundation myth, including versions in which Remus founds a city named Remuria, five miles from Rome, and outlives his brother Romulus.[11][12]

A different and probably late tradition has Acca Larentia as a sacred prostitute (one of many Roman slangs for prostitute was lupa (she-wolf)).[13][14]

Etymology edit

As king, Romulus organises Rome's administration according to tribe; one of Latins (Ramnes), one of Sabines (Titites), and one of Luceres.[15] Each elects a tribune to represent their civil, religious, and military interests.[16] Romulus divides each tribe into ten curiae to form the Comitia Curiata. The thirty curiae derive their individual names from thirty of the kidnapped Sabine women. The individual curiae were further divided into ten gentes, held to form the basis for the nomen in the Roman naming convention. Proposals made by Romulus or the Senate are offered to the Curiate assembly for ratification; the ten gentes within each curia cast a vote, and the matter is carried by whichever gens has a majority.

Quirinus edit

Ennius (fl. 180s BC) refers to Romulus as a divinity in his own right, without reference to Quirinus. Roman mythographers identified the latter as an originally Sabine war-deity, and thus to be identified with Roman Mars. Lucilius lists Quirinus and Romulus as separate deities, and Varro accords them different temples. Images of Quirinus showed him as a bearded warrior wielding a spear as a god of war, the embodiment of Roman strength and a deified likeness of the city of Rome. He had a Flamen Maior called the Flamen Quirinalis, who oversaw his worship and rituals in the ordainment of Roman religion attributed to Romulus's royal successor, Numa Pompilius. There is however no evidence for the conflated Romulus-Quirinus before the 1st century BC.[17][18]

Modern and Renaissance views edit

Modern interpretations edit

For modern scholarship, Romulus and Remus's tale remains one of the most complex and problematic of all foundation myths, particularly in the manner of Remus's death. Ancient historians had no doubt that Romulus gave his name to the city. Most modern historians believe his name a back-formation from the name Rome; the basis for Remus's name and role remain subjects of ancient and modern speculation. Some narratives appear to represent popular or folkloric tradition; some of these remain inscrutable in purpose and meaning. Wiseman sums the whole as the mythography of an unusually problematic foundation and early history.[19][20]

Wiseman sums the whole as the mythography of an unusually problematic foundation and early history.[21] Cornell and others describe particular elements of the mythos as "shameful".[22]

Machiavelli edit

In Machiavelli's The Prince, the 16th century political philosophy points to the ascension of Romulus by his talent and skill as a ruler who came to power by "one's own arms and ability" as opposed to good fortune or happenstance.[23]

- Machiavelli, Niccolò. The Prince, (1908 edition tr by W. K. Marriott) Gutenberg edition

Historicity edit

Modern scholarship offers no support for a historical Romulus, or a Remus. Roman historians and Roman traditions traced most Roman institutions to Romulus; he was thought to have founded Rome's armies, Senate and government, basic laws, citizen rights and responsibilities, religious institutions, earliest political alliances and even the patronage that underpinned both civil and military life. In reality, such developments would have been spread over a considerable span of time; some were much older, and others much more recent.

Any possible historical bases for the broad mythological narrative remain unclear and disputed. The archaeologist Andrea Carandini is one of very few modern scholars who accept Romulus and Remus as historical figures, based on the 1988 discovery of an ancient wall on the north slope of the Palatine Hill in Rome. Carandini dates the structure to the mid-8th century BC and names it the Murus Romuli.[24] In 2007, archaeologists reported the discovery of the Lupercal beneath the home of Emperor Augustus, although a debate over the discovery continues.[25][26]

Depictions edit

Ancient edit

Iconography edit

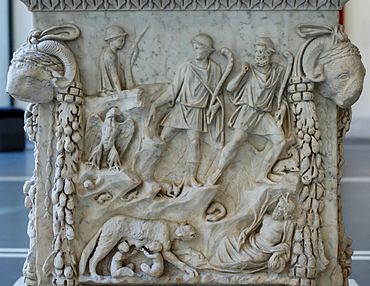

Ancient pictures of the Roman twins usually follow certain symbolic traditions, depending on the legend they follow: they either show a shepherd, the she-wolf, the twins under a fig tree, and one or two birds (Livy, Plutarch); or they depict two shepherds, the she-wolf, the twins in a cave, seldom a fig tree, and never any birds (Dionysius of Halicarnassus).

Also there are coins with Lupa and the tiny twins placed beneath her.

The Franks Casket, an Anglo-Saxon ivory box (early 7th century AD) shows Romulus and Remus in an unusual setting, two wolves instead of one, a grove instead of one tree or a cave, four kneeling warriors instead of one or two gesticulating shepherds. According to one interpretation, and as the runic inscription ("far from home") indicates, the twins are cited here as the Dioscuri, helpers at voyages such as Castor and Polydeuces. Their descent from the Roman god of war predestines them as helpers on the way to war. The carver transferred them into the Germanic holy grove and has Woden's second wolf join them. Thus the picture served — along with five other ones — to influence "wyrd", the fortune and fate of a warrior king.[28]

In popular culture edit

- Romolo e Remo: a 1961 film starring Steve Reeves and Gordon Scott as the two brothers.

- The Rape of the Sabine Women: a 1962 film starring Wolf Ruvinskis as Romulus.

- In the Star Trek universe, Romulus and Remus are neighbouring planets with Remus being tidally locked to the star. Romulus is the capital of the Romulan Star Empire, which is loosely based on the Roman Empire.

- The novel Founding Fathers by Alfred Duggan describes the founding and first decades of Rome from the points of view of Marcus, one of Romulus's Latin followers, Publius, a Sabine who settles in Rome as part of the peace agreement with Tatius, Perperna, an Etruscan fugitive who is accepted into the tribe of Luceres after his own city is destroyed, and Macro, a Greek seeking purification from blood-guilt who comes to the city in the last years of Romulus's reign. Publiusa and Perpernia become senators. Romulus is portrayed as a gifted leader though a remarkably unpleasant person, chiefly distinguished by his luck; the story of his surreptitious murder by the senators is adopted, but although the story of his deification is fabricated, his murderers themselves think he may indeed have become a god. The novel begins with the founding of the city and the killing of Remus, and ends with the accession of Numa Pompilius.

- In the game Undead Knights, the main characters are brothers named Romulus and Remus.

- In Harry Potter, one of the characters is named after Remus—Remus John Lupin. And at one point uses the code name Romulus. Professor Lupin is a teacher of defence against the dark arts, and is in fact a werewolf. This reflects the Remus of Roman mythology, who was raised by a wolf. In fact, the name Lupin comes from the Latin word lupus, meaning wolf.

- In Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood Romulus is worshipped as a god by the Followers of Romulus cult. The main character, Ezio Auditore, comes into conflict with the cult on several occasions during his adventures in Rome while trying to locate the keys to the Armor of Brutus, wiping out the cult in the process.[29]

- In the Death Grips song, "Black Quarterback" Romulus and Remus are mentioned. In characteristic Death Grips style, their lyric isn't contextualised in any typical linear sense.

- "Up the Wolves" by The Mountain Goats is a song that alludes to Romulus and Remus.

- Ex Deo released an album in 2009 titled Romulus. Its title track concerns the myth of Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome.

Footnotes edit

Bibliography edit

Primary sources edit

- Cassius Dio. The Roman History at Project Gutenberg (print: Penguin Books, 1987, ISBN 0-14-044448-3)

- Florus (1889). . Translated by John Selby Watson. London: George Bell & Sons – via Wikisource.

- Livy (1905). . Translated by Canon Roberts – via Wikisource. (print: Book 1 as The Rise of Rome, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-282296-9)

- Plutarch. . Translated by John Dryden – via Wikisource. (print: Jacques Amyot and Thomas North (tr.), Plutarch, Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, Southern Illinois University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-404-51870-2 )

- Polybius: The Rise of the Roman Empire at LacusCurtius (print: Harvard University Press, 1927. (Translation by W. R. Paton), unknown ISBN

- Tacitus (1876). . Translated by Alfred John Church & William Jackson Brodribb. New York: Random House, Inc. – via Wikisource.

- Tacitus (1876). . Translated by Alfred John Church & William Jackson Brodribb. New York: Random House, Inc. – via Wikisource. (print: Penguin Books, 1975, ISBN 0-14-044150-6)

See also edit

- Asena, a similar legend concerning the origin of the Turks

- Proto-Indo-European religion, §Brothers

- The Golden Bough, a tale concerning Aeneas and Rome

References edit

- ^ Beard, Mary (1998), Religions of Rome: Volume I, A history, Cambridge University Press, p. xii.

- ^ For other depictions, see sections for Livy and Dionysius

- ^ #Dionysius lays out several of the different accounts of his death, including his murder by Romulus.

- ^ According to #Cicero he is murdered by disgruntled senators who hide his body by carrying each a bloody portion of it away with them

- ^ Beard, Mary (1998), Religions of ROme: Volume I, A history, Cambridge University Press, p. xii.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio (1914). "Roman History Vol I": 13. doi:10.4159/DLCL.dio_cassius-roman_history.1914. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required) Cite error: The named reference "Dio-I" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Plutarch also recourts Livy's tale of the conquest of Fidenae after the union of the Sabines, Parallel Lives Romulus 23 pg 5

- ^ Plutarch also recourts Livy's tale of the conquest of Fidenae after the union of the Sabines, Parallel Lives Romulus 23 pg 5

- ^ of Halicarnassus, Dionysius, Thayer (ed.), Roman Antiquities, Chicago, IL, USA: Loeb, pp. 1, 72–90, 2, 1–76.

- ^ Plutarch, "The life of Romulus", in Thayer (ed.), The Parallel Lives, Chicago, IL, USA: Loeb.

- ^ Cornell, pp. 57-8.

- ^ Banchich (2004), Origo Gentis Romanae (PDF), trans. by Haniszewski, et al., Cansius College. Translation and commentaries.

- ^ Livy, (i), p. 4.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti, p. 55.

- ^ In Varro, the Ramnes derive their name from Romulus, the Titites derived their name from Titus Tatius, and the Luceres derived their name from an Etruscan leader or his title of honour: Livy, 1.13 describes the origin of the Luceres as unknown.

- ^ The tribunes were magistrates of their tribes, performed sacrifices on their behalf, and commanded their tribal levies in times of war.

- ^ Evans, 103 and footnote 66: citing quotation of Ennius in Cicero, 1.41.64.

- ^ Fishwick, Duncan (1993), The Imperial Cult in the Latin West (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill, p. 53, ISBN 90-04-07179-2.

- ^ Wiseman, TP (1995), Remus, A Roman myth, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Momigliano, Arnoldo (2007), "An interim report on the origins of Rome", Terzo contributo alla storia degli studi classici e del mondo antico, vol. 1, Rome, IT: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, pp. 545–98, ISBN 9788884983633. A critical, chronological review of historiography related to Rome's origins.

- ^ Wiseman, TP (1995), Remus, A Roman myth, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Cornell, pp 60–2: "these elements have convinced the eminent historiographer H. Strasburger that Rome's foundation myth represents not native tradition but defamatory foreign propaganda, probably originated by Rome's neighbours in Magna Graecia and successfully foist on an impressionable and ethnically confused Roman people." Cornell and Momigliano find this argument impeccably developed but entirely implausible; if an exercise in mockery, it was a signal failure.

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli (1910), The Prince, P.F. Collier, pp. 20–21

- ^ See Carandini, La nascita di Roma. Dèi, lari, eroi e uomini all'alba di una civiltà (Torino: Einaudi, 1997) and Carandini. Remo e Romolo. Dai rioni dei Quiriti alla città dei Romani (775/750 - 700/675 a. C. circa) (Torino: Einaudi, 2006)

- ^ Valsecchi, Maria Cristina (26 January 2007). "Sacred Cave of Rome's Founders Discovered, Archaeologists Say". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Schulz, Matthia. "Is Italy's Spectacular Find Authentic?" Spiegel Online, 10 November 2016.

- ^ Adriano La Regina, "La lupa del Campidoglio è medievale la prova è nel test al carbonio". La Repubblica. 9 July 2008

- ^ [1]; see also "The Travelling Twins: Romulus and Remus in Anglo-Saxon England

- ^ Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood

Further reading edit

- Albertoni, Margherita, et al. The Capitoline Museums: Guide. Milan: Electa, 2006. For information on the Capitoline She-Wolf.

- Beard, M., North, J., Price, S., Religions of Rome, vol. 1, illustrated, reprint, Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-31682-0

- Cornell, T., The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC), Routledge, 1995. ISBN 978-0-415-01596-7

- Wiseman, T. P., Remus: a Roman myth, Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-521-48366-7

External links edit

- Plutarch (Lives of Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Camillus)

- Romulus and Remus (Romwalus and Reumwalus) and two wolves on the Franks Casket: Franks Casket, Helpers on the way to war

- Romulous and Remus on the Ara Pacis Augustae

[[Category:8th-century BC Romans]] [[Category:Kings of Rome]] [[Category:Sibling duos]] [[Category:City founders]] [[Category:Founding monarchs]] [[Category:Feral children]] [[Category:Roman mythology]] [[Category:Divine twins]] [[Category:Demigods of Classical mythology]] [[Category:Deified people]] [[Category:Myth of origins]]