Jackson is the capital of and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi. Along with Raymond, Jackson is one of two county seats for Hinds County. The city had a population of 153,701 at the 2020 census, a significant decline from 173,514, or 11.42%, since the 2010 census, representing the largest decline in population during the decade of any major U.S. city.[4] Jackson is the anchor for the Jackson metropolitan statistical area, the largest metropolitan area located entirely in the state and the tenth-largest urban area in the Deep South. With a 2020 population of nearly 600,000, metropolitan Jackson is home to over one-fifth of Mississippi's population. The city sits on the Pearl River and is located in the greater Jackson Prairie region of Mississippi. Jackson is the only city in Mississippi with a population exceeding 100,000 people.

Jackson | |

|---|---|

| Motto: The City with Soul | |

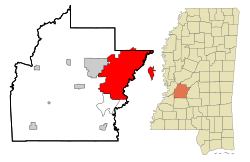

Location of Jackson in Hinds County, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 32°17′56″N 90°11′05″W / 32.29889°N 90.18472°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties | Hinds, Madison, Rankin |

| Incorporated | 1822 |

| Named for | Andrew Jackson |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Chokwe Antar Lumumba (D) |

| • Council | Members

|

| Area | |

| • State capital city | 113.85 sq mi (294.88 km2) |

| • Land | 111.72 sq mi (289.34 km2) |

| • Water | 2.14 sq mi (5.53 km2) |

| Elevation | 279 ft (85 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • State capital city | 153,701 |

| • Rank | US: 149th |

| • Density | 1,375.82/sq mi (531.21/km2) |

| • Urban | 347,693 (US: 118th) |

| • Urban density | 1,466.1/sq mi (566.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 591,978 (US: 99th) |

| Demonym | Jacksonian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 39201-39213, 39215-39218, 39225, 39232, 39236, 39250, 39269, 39271-39272, 39282-39284, 39286, 39288-39289, 39296, 39298 |

| Area codes | 601, 769 |

| FIPS code | 28-36000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0711543[3] |

| Website | www |

| For additional city data see City-Data | |

Founded in 1821 as new state capital for Mississippi, Jackson is named after General Andrew Jackson, a war hero in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812 and subsequently the seventh U.S. president. Following the Battle of Vicksburg, which was fought near Jackson during the American Civil War in 1863, Union forces commanded by General William Tecumseh Sherman launched the siege of Jackson and set the city on fire.[5]

During the 1920s, Jackson surpassed Meridian to become the most populous city in the state following a speculative natural gas boom in the region. The current slogan for the city is "The City with Soul".[6] It has had numerous musicians prominent in blues, gospel, folk, and jazz. The city is located in the deep south halfway between Memphis and New Orleans on Interstate 55 and Dallas and Atlanta on Interstate 20.

The city has a number of museums and cultural institutions, including the Mississippi Children's Museum, Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, Mississippi Museum of Art, Old Capital Museum, Museum of Mississippi History. Other notable locations are the Mississippi Coliseum and the Mississippi Veterans Memorial Stadium, home of the Jackson State Tigers football team.

The Jackson metropolitan statistical area is the state's second-largest metropolitan area.[7] In 2020, the Jackson metropolitan area held a GDP of 30 billion dollars, accounting for 29% of the state's total GDP of 104.1 billion dollars.

History

editFounding and antebellum period (to 1860)

editLocated on the historic Natchez Trace trade route, created by Native Americans and used by European American settlers, and on the Pearl River, the city's first European American settler was Louis LeFleur, a French-Canadian trader. The village became known as LeFleur's Bluff.[8] During the late 18th century and early 19th century, this site had a trading post. It was connected to markets in Tennessee. Soldiers returning to Tennessee from the military campaigns near New Orleans in 1815 built a public road that connected Lake Pontchartrain in Louisiana to this district.[9] A United States treaty with the Choctaw, the Treaty of Doak's Stand in 1820, formally opened the area for non-Native American settlers.

LeFleur's Bluff was developed when it was chosen as the site for the new state's capital city. The Mississippi General Assembly decided in 1821 that the state needed a centrally located capital (the legislature was then located in Natchez). They commissioned Thomas Hinds, James Patton, and William Lattimore to look for a suitable site. The absolute center of the state was a swamp, so the group had to widen their search.

After surveying areas north and east of Jackson, they proceeded southwest along with the Pearl River until they reached LeFleur's Bluff in today's Hinds County.[8] Their report to the General Assembly stated that this location had beautiful and healthful surroundings, good water, abundant timber, navigable waters, and proximity to the Natchez Trace. The Assembly passed an act on November 28, 1821, authorizing the site as the permanent seat of the government of the state of Mississippi.[8] On the same day, it passed a resolution to instruct the Washington delegation to press Congress for a donation of public lands on the river for improved navigation to the Gulf of Mexico.[10] One Whig politician lamented the new capital as a "serious violation of principle" because it was not at the absolute center of the state.[11]

The capital was named for General Andrew Jackson, to honor his January 1815 victory at the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. He was later elected as the seventh president of the United States.

The city of Jackson was originally planned, in April 1822, by Peter Aaron Van Dorn in a "checkerboard" pattern advocated by Thomas Jefferson.[12] City blocks alternated with parks and other open spaces. Over time, many of the park squares have been developed rather than maintained as green space. The state legislature first met in Jackson on December 23, 1822. In 1839, the Mississippi Legislature passed the first state law in the U.S. to permit married women to own and administer their own property.[13]

Jackson was connected by public road to Vicksburg and Clinton in 1826.[14] Jackson was first connected by railroad to other cities in 1840. An 1844 map shows Jackson linked by an east–west rail line running between Vicksburg, Raymond, and Brandon. Unlike Vicksburg, Greenville, and Natchez, Jackson is not located on the Mississippi River, and it did not develop during the antebellum era as those cities did from major river commerce. The construction of railroad lines to the city sparked its growth in the decades following the American Civil War.

American Civil War

editDespite its small population, during the Civil War, Jackson became a strategic center of manufacturing for the Confederacy. In 1863, during the military campaign which ended in the capture of Vicksburg, Union forces captured Jackson during two battles—once before the fall of Vicksburg and once after the fall of Vicksburg.

On May 13, 1863, Union forces won the first Battle of Jackson, forcing Confederate forces to flee northward towards Canton. On May 14, Union troops under the command of William Tecumseh Sherman burned and looted key facilities in Jackson, a strategic manufacturing and railroad center for the Confederacy.[15][16] After driving the Confederate forces out of Jackson, Union forces turned west and engaged the Vicksburg defenders at the Battle of Champion Hill in nearby Edwards. The Union forces began their siege of Vicksburg soon after their victory at Champion Hill. Confederate forces began to reassemble in Jackson in preparation for an attempt to break through the Union lines surrounding Vicksburg and end the siege. The Confederate forces in Jackson built defensive fortifications encircling the city while preparing to march west to Vicksburg.

Confederate forces marched out of Jackson in early July 1863 to break the siege of Vicksburg. But, unknown to them, Vicksburg had already surrendered on July 4, 1863. General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched General Sherman to meet the Confederate forces heading west from Jackson. Upon learning that Vicksburg had already surrendered, the Confederates retreated into Jackson. Union forces began the siege of Jackson, which lasted for approximately one week. Union forces encircled the city and began an artillery bombardment. One of the Union artillery emplacements has been preserved on the grounds of the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson. Another Federal position is preserved on the campus of Millsaps College. John C. Breckinridge, former United States vice president, served as one of the Confederate generals defending Jackson. On July 16, 1863, Confederate forces slipped out of Jackson during the night and retreated across the Pearl River.

Union forces completely burned the city after its capture this second time. The city was called "Chimneyville" because only the chimneys of houses were left standing.[15] The northern line of Confederate defenses in Jackson during the siege was located along a road near downtown Jackson, now known as Fortification Street.

Because of the siege and following destruction, few antebellum structures have survived in Jackson. The Governor's Mansion, built in 1842, served as Sherman's headquarters and has been preserved. Another is the Old Capitol building, which served as the home of the Mississippi state legislature from 1839 to 1903. The Mississippi legislature passed the ordinance of secession from the Union there on January 9, 1861, becoming the second state to secede from the United States. The Jackson City Hall, built in 1846 for less than $8,000, also survived. It is said that Sherman, a Mason, spared it because it housed a Masonic Lodge, though a more likely reason is that it housed an army hospital.[17]

Reconstruction

editDuring Reconstruction, African Americans were granted civil rights. Schools were established and African Americans held political offices. Eugene Welborne, Charles Reese, Weldon Hicks, and George Caldwell Granberry were among the legislators who represented Hinds County in the legislature. African Americans also served in local offices, as judges, and as marshalls.

Mississippi had considerable insurgent action, as whites struggled to maintain white supremacy. Jackson's appointed mayor Joseph G. Crane was stabbed to death in 1869. The assailant, Edward M. Yerger, was arrested by military authorities but, after a U.S. Supreme Court case (Ex parte Yerger), he was bonded out, moved to Baltimore and was never tried.

The economic recovery from the Civil War was slow through the start of the 20th century, but there were some developments in transportation. In 1871, the city introduced mule-drawn streetcars which ran on State Street, which were replaced by electric ones in 1899.[18] In 1875, the Red Shirts were formed, one of the second waves of insurgent paramilitary organizations that essentially operated as "the military arm of the Democratic Party" to take back political power from the Republicans and to drive black people from the polls (Mississippi Plan).[19]

Post-Reconstruction

editDemocrats regained control of the state legislature in 1876. The constitutional convention of 1890, which produced Mississippi's Constitution of 1890, was held at the capitol.[20] This was the first of new constitutions or amendments ratified in each Southern state through 1908 that effectively disenfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites, through provisions making voter registration more difficult: such as poll taxes, residency requirements, and literacy tests. These provisions survived a Supreme Court challenge in 1898.[21][22] As 20th-century Supreme Court decisions later ruled such provisions were unconstitutional, Mississippi and other Southern states rapidly devised new methods to continue disfranchisement of most black people, who comprised a majority in the state until the 1930s. Their exclusion from politics was maintained into the late 1960s.

The so-called New Capitol replaced the older structure upon its completion in 1903. Today the Old Capitol is operated as a historical museum.[20]

Early 20th century (1901–1960)

editAuthor Eudora Welty was born in Jackson in 1909, lived most of her life in the Belhaven section of the city, and died there in 2001. Her memoir of development as a writer, One Writer's Beginnings (1984), presented a picture of the city in the early 20th century. She won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973 for her novel, The Optimist's Daughter, and is best known for her novels and short stories. The main library of the Jackson/Hinds Library System was named in her honor,[23] and her home has been designated as a National Historic Landmark.

Richard Wright, a highly acclaimed African-American author, lived in Jackson as an adolescent and young man in the 1910s and 1920s. He related his experience in his memoir Black Boy (1945). He described the harsh and largely terror-filled life most African Americans experienced in the South and Northern ghettos such as Chicago under segregation in the early 20th century.

Jackson had significant growth in the early 20th century, which produced dramatic changes in the city's skyline. Jackson's new Union Station downtown reflected the city's service by multiple rail lines, including the Illinois Central.

Across the street, the new, luxurious King Edward Hotel opened its doors in 1923, having been built according to a design by New Orleans architect William T. Nolan. It became a center for prestigious events held by Jackson society and Mississippi politicians. Nearby, the 18-story Standard Life Building, designed in 1929 by Claude Lindsley, was the largest reinforced concrete structure in the world upon its completion.

Jackson's economic growth was further stimulated in the 1930s by the discovery of natural gas fields nearby. Speculators had begun searching for oil and natural gas in Jackson beginning in 1920. The initial drilling attempts came up empty. This failure did not stop Ella Render from obtaining a lease from the state's insane asylum to begin a well on its grounds in 1924, where he found natural gas. (Render eventually lost the rights when courts determined that the asylum did not have the right to lease the state's property.) Businessmen jumped on the opportunity and dug wells in the Jackson area. The continued success of these ventures attracted further investment. By 1930, there were 14 derricks in the Jackson skyline.

Mississippi Governor Theodore Bilbo stated:

It is no idle dream to prophesy that the state's share [of the oil and natural gas profits] properly safe-guarded would soon pay the state's entire bonded indebtedness and even be great enough to defray all the state's expenses and make our state tax free so long as obligations are concerned.

This enthusiasm was subdued when the first wells failed to produce oil of a sufficiently high gravity for commercial success. The barrels of oil had considerable amounts of saltwater, which lessened the quality. The governor's prediction was wrong in hindsight, but the oil and natural gas industry did provide an economic boost for the city and state. The effects of the Great Depression were mitigated by the industry's success. At its height in 1934, there were 113 producing wells in the state. The overwhelming majority were closed by 1955.[24]

Due to provisions in the federal Rivers and Harbors Act, on October 25, 1930, city leaders met with U.S. Army engineers to ask for federal help to alleviate Jackson flooding.[25] J.J. Halbert, city engineer, proposed a straightening and dredging of the Pearl River below Jackson.[26]

Jackson's Gold Coast

editDuring Mississippi's extended Prohibition period, from the 1920s until the 1960s, illegal drinking and gambling casinos flourished on the east side of the Pearl River, in Flowood along with the original U.S. Route 80 just across from the city of Jackson. Those illegal casinos, bootleg liquor stores, and nightclubs made up the Gold Coast, a strip of mostly black-market businesses that operated for decades along Flowood Road. Although outside the law, the Gold Coast was a thriving center of nightlife and music, with many local blues musicians appearing regularly in the clubs.

The Gold Coast declined and businesses disappeared after Mississippi's prohibition laws were repealed in 1966, allowing Hinds County, including Jackson, to go "wet".[27] In addition, integration drew off business from establishments that earlier had catered to African Americans, such as the Summers Hotel. When it opened in 1943 on Pearl Street, it was one of two hotels in the city that served black clients. For years its Subway Lounge was a prime performance spot for black musicians playing jazz and blues.

In another major change, in 1990 the state-approved gaming on riverboats.[28] Numerous casinos have been developed on riverboats, mostly in Mississippi Delta towns such as Tunica Resorts, Greenville, and Vicksburg, as well as Biloxi on the Gulf Coast. Before the damage and losses due to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the state ranked second nationally in gambling revenues[citation needed].

World War II and later development

editDuring World War II, Hawkins Field (at that time, also known as the Jackson Army Airbase) the American 21st, 309th, and 310th Bomber Groups that were stationed at the base were re-deployed for combat.[29] Following the German invasion of the Netherlands and the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies, between 688 and 800 members of the Dutch Airforce escaped to the UK or Australia for training and, out of necessity, were eventually given permission by the United States to make use of Hawkins Field.[30]

From May 1942 until the end of the war, all Dutch military aircrews trained at the base and went on to serve in either the British or Australian Air Forces.[31]

In 1949, the poet Margaret Walker began teaching at Jackson State University, a historically black college. She taught there until 1979 and founded the university's Center for African-American Studies. Her poetry collection won a Yale Younger Poets Prize. Her second novel, Jubilee (1966), is considered a major work of African-American literature. She has influenced many younger writers.

Civil rights movement in Jackson

editThe civil rights movement had been active for decades, particularly mounting legal challenges to Mississippi's constitution and laws that disfranchised black people. Beginning in 1960, Jackson as the state capital became the site for dramatic non-violent protests in a new phase of activism that brought in a wide variety of participants in the performance of mass demonstrations.

In 1960, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Jackson's population as 64.3% white and 35.7% black.[32] At the time, public facilities were segregated and Jim Crow was in effect. Efforts to desegregate Jackson facilities began when nine Tougaloo College students tried to read books in the "white only" public library and were arrested. Founded as a historically black college (HBCU) by the American Missionary Association after the Civil War, Tougaloo College helped organize both black and white students of the region to work together for civil rights. It created partnerships with the neighboring mostly white Millsaps College to work with student activists. It has been recognized as a site on the "Civil Rights Trail" by the National Park Service.[33]

The mass demonstrations of the 1960s were initiated with the arrival of more than 300 Freedom Riders on May 24, 1961. They were arrested in Jackson for disturbing the peace after they disembarked from their interstate buses. The interracial teams rode the buses from Washington, D.C., and sat together to demonstrate against segregation on public transportation, as the Constitution provides for unrestricted public transportation.[34] Although the Freedom Riders had intended New Orleans as their final destination, Jackson was the farthest that any managed to travel. New participants kept joining the movement, as they intended to fill the jails in Jackson with their protest. The riders had encountered extreme violence along the way, including a bus burning and physical assaults. They attracted national media attention to the struggle for constitutional rights.

After the Freedom Rides, students and activists of the Freedom Movement launched a series of merchant boycotts,[35] sit-ins and protest marches,[36] from 1961 to 1963. Businesses discriminated against black customers. For instance, at the time, department stores did not hire black salesclerks or allow black customers to use their fitting rooms to try on clothes, or lunch counters for meals while in the store, but they wanted them to shop in their stores.

In Jackson, shortly after midnight on June 12, 1963, Medgar Evers, civil rights activist and leader of the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP, was assassinated by Byron De La Beckwith, a white supremacist associated with the White Citizens' Council. Thousands marched in Evers' funeral procession to protest the killing.[37] Two trials at the time both resulted in hung juries. A portion of U.S. Highway 49, all of Delta Drive, a library, the central post office for the city, and Jackson–Evers International Airport were named in honor of Medgar Evers. In 1994, prosecutors Ed Peters and Bobby DeLaughter finally obtained a murder conviction in a state trial of De La Beckwith based on new evidence.[38]

During 1963 and 1964, civil rights organizers gathered residents for voter education and voter registration. Black people had been essentially disfranchised since 1890. In a pilot project in 1963, activists rapidly registered 80,000 voters across the state, demonstrating the desire of African Americans to vote. In 1964 they created the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as an alternative to the all-white state Democratic Party, and sent an alternate slate of candidates to the national Democratic Party convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, that year.

Segregation and the disfranchisement of African Americans gradually ended after the Civil Rights Movement gained Congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. In June 1966, Jackson was the terminus of the James Meredith March, organized by James Meredith, the first African American to enroll at the University of Mississippi. The march, which began in Memphis, Tennessee, was an attempt to garner support for full implementation of civil rights in practice, following the legislation. It was accompanied by a new drive to register African Americans to vote in Mississippi. In this latter goal, it succeeded in registering between 2,500 and 3,000 black Mississippians to vote. The march ended on June 26 after Meredith, who had been wounded by a sniper's bullet earlier on the march, addressed a large rally of some 15,000 people in Jackson.

In September 1967 a Ku Klux Klan chapter bombed the synagogue of the Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, and in November bombed the house of its rabbi, Dr. Perry Nussbaum.[39] He and his congregation had supported civil rights.

Gradually the old barriers came down. Since that period, both whites and African Americans in the state have had a consistently high rate of voter registration and turnout. Following the decades of the Great Migration, when more than one million black people left the rural South, since the 1930s the state has been majority white in total population. African Americans are a majority in the city of Jackson, although the metropolitan area is majority white. African Americans are also a majority in several cities and counties of the Mississippi Delta, which are included in the 2nd congressional district.[40] The other three congressional districts are majority white.

Mid-1960s to present

editThe first successful cadaveric lung transplant was performed at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson in June 1963 by Dr. James Hardy. Hardy transplanted the cadaveric lung into a patient suffering from lung cancer. The patient survived for eighteen days before dying of kidney failure.[41]

In 1966 it was estimated that recurring flood damage at Jackson from the Pearl River averaged nearly a million dollars per year. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spent $6.8 million on levees and a new channel in 1966 before the project completion to prevent a flood equal to the December 1961 event plus an additional foot.[42]

Since 1968, Jackson has been the home of Malaco Records, one of the leading record companies for gospel, blues, and soul music in the United States. In January 1973, Paul Simon recorded the songs "Learn How to Fall" and "Take Me to the Mardi Gras", found on the album There Goes Rhymin' Simon, in Jackson at the Malaco Recording Studios. Many well-known Southern artists recorded on the album, including the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section (David Hood, Jimmy Johnson, Roger Hawkins, Barry Beckett), Carson Whitsett, the Onward Brass Band from New Orleans, and others. The label has recorded many leading soul and blues artists, including Bobby Bland, ZZ Hill, Latimore, Shirley Brown, Denise LaSalle, and Tyrone Davis.

On May 15, 1970, Jackson police killed two students and wounded twelve at Jackson State College after a protest of the Vietnam War included students' overturning and burning some cars. These killings occurred eleven days after the National Guard killed four students in an anti-war protest at Kent State University in Ohio, and were part of national social unrest.[43] Newsweek cited the Jackson State killings in its issue of May 18 when it suggested that U.S. President Richard Nixon faced a new home front.

The influx of illegal drugs occurred nationally as smugglers used the highways, seaports, and airports of the Gulf region.[44][45] The 1980s in Jackson were dominated by Mayor Dale Danks Jr. until he was unseated by lawyer and legislator J. Kane Ditto, who criticized the deficit funding and the politicized police department of the city.[46] Federal investigations of drug trafficking at Jackson's Hawkins Field airport were a part of the Kerry Report, the 1986 U.S. Senate investigation of public corruption and foreign relations.[47]

As Jackson has become the medical and legal center of the state, it has attracted Jewish professionals in both fields. Since the late 20th century, it has developed the largest Jewish community in the state.[48]

In 1997, Harvey Johnson, Jr. was elected as Jackson's first African-American mayor. During his term, he proposed the development of a convention center to attract more business to the city. In 2004, during his second term, 66 percent of the voters passed a referendum for a tax to build the Convention Center.[49]

Mayor Johnson was replaced by Frank Melton on July 4, 2005. Melton generated controversy through his unconventional behavior, which included acting as a law enforcement officer. A dramatic spike in crime ensued during his term, despite Melton's efforts to reduce crime. The lack of jobs contributed to crime.[50] In 2006 a young African-American businessman, Starsky Darnell Redd, was convicted of money laundering in federal court along with his mother, other associates, and Billy Tucker, the former airport security chief.[51]

In 2007, Hinds County sheriff Malcolm McMillin was appointed as the new police chief in Jackson, setting a historic precedent. McMillin was both the county sheriff and city police chief until 2009, when he stepped down due to disagreements with the mayor. Mayor Frank Melton died in May 2009, and City Councilman Leslie McLemore served as acting mayor of Jackson until July 2009, when former Mayor Harvey Johnson was elected and assumed the position.[52]

On June 26, 2011, 49-year-old James Craig Anderson was killed in Jackson after being beaten, robbed, and run over by a group of white teenagers. The district attorney described it as a "hate crime", and the FBI investigated it as a civil rights violation.[53][54][55]

On March 18, 2013, a severe hailstorm hit the Jackson metro area. The hail caused major damage to roofs, vehicles, and building siding. Hail ranged in size from golfball to softball. There were more than 40,000 hailstorm claims of homeowner and automobile damage.[56][57]

In 2013, Jackson was named as one of the top 10 friendliest cities in the United States by CN Traveler. The capital city was tied with Natchez as Number 7. The city was noticed for friendly people, great food, and green and pretty public places.[58]

On July 1, 2013, Chokwe Lumumba was sworn into office as mayor of the city. After eight months in office, Lumumba died on February 25, 2014. Lumumba was a popular yet controversial figure due to his prior membership in the Republic of New Afrika, as well as being a co-founder of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America.

Lumumba's son, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, ran for the mayoral seat following his father's death, but lost to Councillor Tony Yarber on April 22, 2014.[59] In 2017, however, Chokwe Antar Lumumba ran for mayor again, and won. Following his victory, on June 26 he was interviewed by Amy Goodman on Democracy Now!,[60] at which time he declared a commitment to make Jackson the "Most Radical City on the Planet".

For several years, the city water supply failed to meet federal drinking water standards and was subject to many boil water orders in 2021 and 2022. Due to deteriorating water infrastructure, some parts of the city experienced low water pressure, and in some neighborhoods residents reported untreated sewage flowing in city streets.[61] In August 2022, Jackson lost access to water when its largest water treatment plant failed, leaving tap water untreated.[62]

Geography

editJackson is located primarily in northeastern Hinds County, with small portions in Madison and Rankin counties. The city of Jackson also includes around 3,000 acres (12.1 km2) comprising Jackson-Medgar Evers International Airport in Rankin County and a small portion of Madison County. The Pearl River forms most of the eastern border of the city. A small portion of the city containing Tougaloo College is the portion of Jackson that lies in Madison County, bounded on the west by Interstate 220 and on the east by the U.S. Route 51 and Interstate 55. In the 2010 census, only 622 of the city's residents lived in Madison County,[63] and only 1 lived within the city limits in Rankin County.[64] The city is bordered to the north by Ridgeland in Madison County, to the northeast by Ross Barnett Reservoir on the Pearl River, to the east by Flowood and Richland in Rankin County, to the south by Byram in Hinds County, and to the west by Clinton in Hinds County.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 113.2 square miles (293.3 km2), of which 111.0 square miles (287.6 km2) are land and 2.2 square miles (5.7 km2), or 1.94% of the total, are water.[65]

Cityscape

editDowntown Jackson is situated directly on the banks of the Pearl River. The downtown district has direct connections to both Interstate 55 via Pearl Street and Pasagoula Street and Interstate 20 via State Street (US 51). Much of the downtown was constructed before the 1980s and only small additions to the skyline have been made since then.

Major highways

editGeology

editFor the most part, Jackson is built on acidic, variably drained silt loam soil. Loess forms the topsoil in western sections, where the Loring soil series is common. The Tippo series, also a silt loam, is found in the central flood plain. Farther east, common soil series include Guyton silt loam, Providence silt loam and Smithdale fine sandy loam.[66]

Jackson sits atop the extinct Jackson Volcano, located 2,900 feet (880 m) underground. It is the only capital city in the United States to have this feature. The buried peak of the volcano is located directly below the Mississippi Coliseum.[67] The municipality is drained on the west by tributaries of the Big Black River and on the east by the Pearl River, which is 150 feet (46 m) higher than the Big Black near Canton. The artesian groundwater flow is not as extensive in Jackson for this reason. The first large-scale well was drilled in the city in 1896, and the city water supply has relied on surface water resources.[68]

Climate

editJackson is located in the humid subtropical climate zone (Köppen Cfa). Rain occurs throughout the year, though the winter and spring are the wettest seasons, while September and October are usually the driest months. Snow is rare, and accumulation very seldom lasts more than a day.[69] Average annual precipitation is 57.35 inches (1,457 mm), see climate table.[70] Much of Jackson's rainfall occurs during thunderstorms. Thunder is heard on roughly 70 days each year. Jackson lies in a region prone to severe thunderstorms which can produce large hail, damaging winds, and tornadoes. Among the most notable tornado events was the F5 Candlestick Park tornado on March 3, 1966, which destroyed the shopping center of the same name and surrounding businesses and residential areas, killing 19 in South Jackson.

The record low temperature is −5 °F (−21 °C), set on January 27, 1940,[71] and the record high is 107 °F (42 °C), recorded on September 6–7, 1925, July 29, 1930, and August 30, 2000.[71]

| Climate data for Jackson–Evers International Airport, Mississippi (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1896–present)[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

107 (42) |

107 (42) |

107 (42) |

98 (37) |

89 (32) |

84 (29) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 75.2 (24.0) |

78.6 (25.9) |

83.5 (28.6) |

86.8 (30.4) |

91.9 (33.3) |

95.9 (35.5) |

98.0 (36.7) |

98.6 (37.0) |

95.6 (35.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

81.7 (27.6) |

76.7 (24.8) |

99.7 (37.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57.4 (14.1) |

62.0 (16.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

76.5 (24.7) |

83.8 (28.8) |

89.9 (32.2) |

92.1 (33.4) |

92.2 (33.4) |

87.8 (31.0) |

78.3 (25.7) |

67.2 (19.6) |

59.6 (15.3) |

76.4 (24.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.0 (8.3) |

50.9 (10.5) |

57.9 (14.4) |

64.9 (18.3) |

72.9 (22.7) |

79.6 (26.4) |

82.1 (27.8) |

81.8 (27.7) |

76.9 (24.9) |

66.2 (19.0) |

55.4 (13.0) |

49.1 (9.5) |

65.4 (18.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 36.6 (2.6) |

39.8 (4.3) |

46.4 (8.0) |

53.3 (11.8) |

62.1 (16.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

72.2 (22.3) |

71.5 (21.9) |

66.0 (18.9) |

54.2 (12.3) |

43.6 (6.4) |

38.7 (3.7) |

54.5 (12.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

36.7 (2.6) |

46.9 (8.3) |

59.4 (15.2) |

65.3 (18.5) |

63.6 (17.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

36.8 (2.7) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

1 (−17) |

15 (−9) |

27 (−3) |

36 (2) |

47 (8) |

51 (11) |

54 (12) |

35 (2) |

26 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

4 (−16) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.42 (138) |

5.10 (130) |

5.68 (144) |

5.84 (148) |

4.36 (111) |

4.43 (113) |

5.02 (128) |

4.69 (119) |

3.48 (88) |

3.80 (97) |

4.40 (112) |

5.13 (130) |

57.35 (1,457) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.9 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 11.3 | 10.6 | 6.6 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 110.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.2 | 73.2 | 71.1 | 71.5 | 73.8 | 73.6 | 76.9 | 77.0 | 77.3 | 74.8 | 75.9 | 76.5 | 74.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 154.5 | 165.3 | 223.5 | 251.1 | 276.2 | 298.5 | 283.4 | 273.1 | 232.7 | 235.2 | 174.0 | 152.1 | 2,719.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 48 | 53 | 60 | 65 | 65 | 70 | 65 | 66 | 63 | 67 | 55 | 49 | 61 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[69][71][72] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,881 | — | |

| 1860 | 3,191 | 69.6% | |

| 1870 | 4,234 | 32.7% | |

| 1880 | 5,204 | 22.9% | |

| 1890 | 5,920 | 13.8% | |

| 1900 | 7,816 | 32.0% | |

| 1910 | 21,262 | 172.0% | |

| 1920 | 22,817 | 7.3% | |

| 1930 | 48,282 | 111.6% | |

| 1940 | 62,107 | 28.6% | |

| 1950 | 98,271 | 58.2% | |

| 1960 | 144,422 | 47.0% | |

| 1970 | 153,968 | 6.6% | |

| 1980 | 202,895 | 31.8% | |

| 1990 | 196,637 | −3.1% | |

| 2000 | 184,286 | −6.3% | |

| 2010 | 173,514 | −5.8% | |

| 2020 | 153,701 | −11.4% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 145,995 | [73] | −5.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[74] 2020 census[75] | |||

Jackson remained a small town for much of the 19th century. Before the American Civil War, Jackson's population remained small, particularly in contrast to the river towns along the commerce-laden Mississippi River. Despite the city's status as the state capital, the 1850 census counted only 1,881 residents, excluding slaves, which were not returned separately.[76]

By 1900 the population of Jackson was still less than 8,000. Although it expanded rapidly, during this period Meridian became Mississippi's largest city, based on trade, manufacturing, and access to transportation via railroad and highway.

In the early 20th century, Jackson had its largest rates of growth but ranked second to Meridian in Mississippi. By 1944, Jackson's population had risen to some 70,000 inhabitants, and it became the largest city in the state. For several decades, Jackson had the most thriving business districts and the largest public school system in Mississippi.[77][78] It achieved its peak population in the 1980 census of more than 200,000 residents in the city. Since 1980, Jackson has declined in population due to several factors while its surrounding suburban population has increased.[79]

Race and ethnicity

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[80] | Pop 2010[81] | Pop 2020[82] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 50,679 | 31,194 | 25,424 | 27.50% | 17.98% | 16.54% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 129,609 | 137,265 | 120,727 | 70.34% | 79.11% | 78.55% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 213 | 232 | 237 | 0.12% | 0.13% | 0.15% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,045 | 660 | 751 | 0.57% | 0.38% | 0.49% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 18 | 18 | 30 | 0.01% | 0.01% | 0.02% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 128 | 99 | 362 | 0.07% | 0.06% | 0.24% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 1,113 | 1,323 | 2,951 | 0.60% | 0.76% | 1.92% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,451 | 2,723 | 3,219 | 0.79% | 1.57% | 2.09% |

| Total | 184,256 | 173,514 | 153,701 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

According to the 2010 census,[83] the racial and ethnic makeup of the city was predominantly Black and African American, and non-Hispanic white; in 2020, they remained the largest racial and ethnic composition for the city. This Hispanic or Latino population is the fastest growing racial and ethnic group in the city.[82][84][85]

Income

editAccording to census statistics in 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $30,414, and the median income for a family was $36,003. Males had a median income of $29,166 versus $23,328 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,116. About 19.6% of families and 23.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.7% of those under age 18 and 15.7% of those age 65 or over.[86] At the publication of the 2020 American Community Survey, the city's median household income increased to $35,070; families had a median income of $44,348, married-couple families $74,893, and non-families $22,061.[87]

Crime

editHigh criminal activity, particularly the homicide rate, is a major reoccurring issue in the city. The crime crises has had a negative impact on the city's economy and population. Most parts of Jackson are considered a food desert because important grocery stores and restaurants have closed down or left the city as theft and other crimes worsen since 2000.[88][89][90]

In 2020, the city's homicide rate reached its highest in history with 79.69 homicides per 100,000 residents, with a total of 128 homicides.[91] Of major U.S. cities, only St. Louis surpassed Jackson's homicide rate.[92] The homicide rate in 2020 represented a significant spike after years of declining homicide rates in the early 2000s.[93] Property crime remains much lower than in the 1990s and overall violent crime has not increased as significantly as homicide in recent years and is below the peak in 1994 as of 2020.[94]

In 2021, a record number of homicides (155) were recorded, and at a rate of 101 per 100,000 was the highest in the United States.[95] In late 2020, Police Chief James Davis along with the Mayor and other city leaders unveiled the virtual policing concept. After months of struggling to move the concept forward, Chief Davis began discussions with Eric B. Fox, a veteran Jackson Police Officer to return to the department.[citation needed] Fox returned officially in January 2022, and launched a new concept, the Real Time Command Center.[citation needed]

Also in 2021, the Jackson Police Department stated that the city had a serious street gang problem which is a major contributor to violent crimes. The city has had a gang presence since the 1980s but it has seemingly grown over the years. Several gangs from Chicago have settled in the city and are heavily involved in drug-selling territory wars and many other crimes.[96][97]

In 2022, for the second year in a row Jackson had the highest homicide rate per capita in the United States.[98]

In 2023, Mayor Lumumba announced the opening of the Jackson Crime Center which is a facility that houses monitoring cameras strategically placed around the city to better identify criminals so they can be held accountable for their actions.[99] The Jackson Police Department is short-staffed so the center will help the department as they work to increase recruitment and retention.[100] Also in 2023, Jackson murders dropped by 15% but the city still had the nation's highest homicide rate per capita.[101]

In February 2024, Governor Reeves announced a new and tougher plan to lower rampant crime in the city and protect innocent residents.[102]

Economy

editJackson is home to several major industries; these include electrical equipment and machinery, processed food, and primary and fabricated metal products. The surrounding area supports the agricultural development of livestock, soybeans, cotton, and poultry.

According to the city's government, Jackson's top three employers are the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson Public Schools, and Nissan North America as of 2020.[103] Other notable corporations with a large presence in the city and area include C Spire and Amazon in nearby Madison County.[104]

The city is home to Cooperation Jackson, which is an economic development vehicle for worker-owned cooperative business.[105] The organization has led to the creation of several businesses including lawn care provider The Green Team, organic farm Freedom Farms, print shop The Center for Community Production, and The Balagoon Center, which is a cooperative business incubator.[106]

Arts and culture

editJackson is home to a number of cultural and artistic attractions, including the following:

- Ballet Mississippi[107]

- Celtic Heritage Society of Mississippi[108]

- Crossroads Film Society and its annual Film Festival[109]

- International Museum of Muslim Cultures[110]

- Jackson State University Botanical Garden

- Jackson Zoo

- Kinetic Etchings Dance project

- Light and Glass Studio[111]

- Margaret Walker Center

- Mississippi Agriculture and Forestry Museum[112]

- Mississippi Arts Center[113]

- Mississippi Chorus[114]

- Mississippi Civil Rights Museum[115]

- Mississippi Department of Archives and History,[116] which contains the state archives and records

- Mississippi Heritage Trust[117]

- Mississippi Hispanic Association[118]

- Mississippi Metropolitan Ballet[119]

- Mississippi Museum of Art[120]

- Mississippi Opera

- Mississippi Shakespeare Festival

- Mississippi Symphony Orchestra (MSO), formerly the Jackson Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1944

- Municipal Art Gallery[121]

- Museum of Mississippi History

- Mynelle Gardens

- New Stage Theatre[122]

- Russell C. Davis Planetarium[123]

- Smith-Robertson Museum and Cultural Center[124]

- USA International Ballet Competition[125]

Notable restaurants

editSports

editThe city of Jackson and its metropolitan area are home to collegiate and semi-professional sports teams; Major League Baseball's Atlanta Braves minor affiliate, the Mississippi Braves, plays in the area. Mississippi Brilla of USL League Two also operates in the area.

Government and infrastructure

editMunicipal government

editIn 1985, Jackson voters opted to replace the three-person mayor-commissioner system with a city council and mayor. This electoral system enables a wider representation of residents on the city council. City council members are elected from each of the city's seven wards, considered single-member districts. The mayor is elected at-large citywide.

Jackson's mayor is Chokwe Antar Lumumba[126] (D), who was elected on July 3, 2017.[127]

Jackson's City Council members are:

- Ward 1: Ashby Foote

- Ward 2: Angelique C. Lee

- Ward 3: Kenneth Stokes

- Ward 4: Brian C. Grizzell

- Ward 5: Vernon W. Hartly

- Ward 6: Aaron Banks

- Ward 7: Virgi Lindsay[128]

State government

editThe Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) operates the Jackson Probation & Parole Office in Jackson.[129] The MDOC Central Mississippi Correctional Facility, in unincorporated Rankin County,[130] is located in proximity to Jackson.[131]

Federal representation

editThe larger portion of Jackson is part of Mississippi's 2nd congressional district. U.S. Representative Bennie Gordon Thompson, a Democrat, has served since 1993. Until 2011 he was Chairman of the Committee on Homeland Security and has been the ranking member since 2011.[1]

The United States Postal Service operates the Jackson Main Post Office[132] and several smaller post offices.

Education

editHigher education

editJackson is home to the most collegiate institutions in Mississippi. Jackson State University is the largest collegiate institution in the city, fourth largest in the state, and the only doctoral-granting research institution based in its region.[133][134]

Colleges and universities

editSource:[135]

- Jackson State University

- Tougaloo College

- Millsaps College

- Belhaven University

- University of Mississippi Medical Center

- Mississippi College School of Law

- Hinds Community College

Primary and secondary schools

editPublic schools

editJackson Public School District (JPS) operates 60 public schools. It is one of the largest school districts in the state with about 30,000 students in thirty-eight elementary schools, thirteen middle schools, seven high schools, and two special schools.[136] Jackson Public Schools is the only urban school district in the state.[137]

As of 2017[update] the public schools have few children who are middle or upper class, as 99% of the students in JPS qualify for free or reduced school lunches. In 2017 Susan Womack, president of the Parents for Public Schools Jackson (PPSJ) from 2000 to 2012, stated that middle to upper-class families in Jackson tended to leave public school after elementary school, with parents who remained in Jackson enrolling their children in private school, and those who wished to continue enrolling their children in public schools moving to Madison County. The PPSJ decided circa the mid-2000s that it was not feasible to encourage middle and upper-class parents to put their children in JPS schools.[138]

The district's high schools include:

While most of Jackson is in Jackson PSD, there are parts in Hinds County that are instead in Hinds County School District.[140] This part is zoned to Terry High School in Terry.[141] The portion of Jackson in Madison County is within the Madison County School District.[142]

There are state-operated K-12 public schools for special purposes;

Private schools

editPrivate secondary schools include:

- Christ Missionary & Industrial (CM&I) College High School

- Hillcrest Christian School

- Jackson Academy

- Woodland Hills Academy (closed)

Some schools are in nearby municipalities:

- St. Andrew's Episcopal Middle and Upper School – North Campus (Ridgeland)

- Jackson Preparatory School (Flowood)

- The Veritas School (Ridgeland), closed

- St. Joseph Catholic School (Madison), of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jackson

- Hartfield Academy (Flowood)

- Madison-Ridgeland Academy (Madison)

- Canton Academy (Canton)

- Tri-County Academy (Flora)

- Central Hinds Academy (Raymond)

- Rebul Academy (Learned)

- East Rankin Academy (Pelahatchie)

Private primary schools include:

- Jackson Academy

- First Presbyterian Day School[143]

- Magnolia Speech School[144]

- St. Andrew's Episcopal Lower School – South Campus

- St. Richard Catholic School[145]

- St. Therese Catholic School

Public libraries

editJackson/Hinds Library System is the library system of Jackson.

Infrastructure

editOn March 27, 2015, Jackson Mayor Tony Yarber issued a state of emergency for transportation (potholes) and water infrastructure (breaks in water mains).[146][147] The quality of Jackson's water infrastructure system decreased after the severe winter weather of 2014–2015. Jackson's office estimated the cost to fix the roads and water pipes at $750 million to $1 billion.[147]

After issuing the state of emergency, the City of Jackson filed a letter of intent to Department of Health to borrow $2.5 million to repair broken water pipes. The Jackson City Council must approve the mayor's proposal.[146] Additionally, Mayor Yarber asked for help from both FEMA and the state Governor's office.[148]

Calling for a state of emergency increases the likelihood that the U.S. Department of Transportation would give the city money from a "quick release" funding account.[149]

In late August 2022, the Pearl River overflowed, flooding much of the city and contaminating the water supply. Mayor Lumumba declared a state of emergency and shut down all businesses and schools.[150]

Transportation

editIn 2015, 11 percent of the city of Jackson households lacked a car, which decreased to 7.6 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Jackson averaged 1.68 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[151]

Jackson has an increasing number of bicycle lanes.[152][153]

Jackson–Medgar Wiley Evers International Airport, the busiest commercial airport in Mississippi, is located east of city in Rankin County between Flowood and Pearl.

Jackson's Union Station serves Amtrak's daily overnight train, the City of New Orleans from Chicago to New Orleans. The intermodal station also serves Greyhound Lines intercity buses and is the primary station for Jackson's municipal buses.

The city is at the intersection of major Interstate and Federal Highways: north-south I-55, US 49, US 51, east–west I-20 and US 80.

In popular culture

editIn 2011, the United States Navy named the USS Jackson (LCS-6) in honor of the city.[154]

In 2002, the Subway Lounge (of the Summers Hotel on the Gold Coast) was featured as the subject of the film documentary entitled Last of the Mississippi Jukes.[155][156]

The popular film The Help (2011), based on the bestselling novel by the same name by Kathryn Stockett, was filmed in Jackson. The city has a two-part, self-guided tour of areas featured in the film and the book.[157]

In the song "Uptown Funk" by Mark Ronson and featuring Bruno Mars Jackson is mentioned in the lines "Julio! Get the Stretch! Ride to Harlem; Hollywood, Jackson, Mississippi."

Get on Up, a movie released in August 2014, had some scenes filmed in Jackson,[158] and nearby Natchez.[159] The movie is based on the life of James Brown.[160]

The movie Speech & Debate, an adaptation of the stage play of the same name of Broadway theatre,[161] was filmed entirely in Jackson.[162]

The Charlie Daniels song "Uneasy Rider" is set in Jackson.

Notable people

editFurther reading

edit- Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi, edited by Kali Akuno and Ajamu Nangwaya. (2017) Daraja Press. ISBN 978-0-9953474-5-8.

Notes

edit- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Jackson have been kept at the international airport since July 8, 1963. For more information, see Threadex

References

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 8, 2023.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Jackson city, Mississippi". Census Bureau QuickFacts. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ "Official City of Jackson, Mississippi Website - History of Jackson". May 10, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2010. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ "Jackson, Mississippi | City With Soul". Jacksoncitywithsoul.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2019". Archived from the original on June 16, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Official City of Jackson, Mississippi Website – Jackson's History". Jacksonms.gov. Archived from the original on May 10, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ Izard, E. Ray. (January 30, 1974) "Carroll's Trace took Tennessee Boys Home". Jackson: Clarion-Ledger.

- ^ Laws of the State of Mississippi passed at the 4th session of the general assembly, held in the City of Natchez. (1821) Natchez: A. Marschalk and Evens & Co. State printers. p. 158.

- ^ William C. Davis, A Way Through the Wilderness: The Natchez Trace and Civilization of the Southern Frontier (New York: Harper Collins, 1995), p. 30

- ^ "Claiborne County MSGenWeb". ancestry.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Gilmer, Robert (November 21, 2003). "Chickasaws, Tribal Laws, and the Mississippi Married Women's Property Act of 1839" (PDF). www.unca.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Brough, Charles H. (1903) "Historic Clinton". Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. v. 7, p.285.

- ^ a b Johnson, Brian. "[Johnson] When Jackson Burned". www.jacksonfreepress.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Vicksburg, Mailing Address: 3201 Clay Street; Us, MS 39183 Phone:636-0583 Contact. "Battle of Jackson (May 14) - Vicksburg National Military Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.NPS.gov. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Thompson, Bennie Gordon (June 19, 2014). "HONORING THE CITY OF JACKSON, MISSISSIPPI". Congressional Record. 160 (97): E1029. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Congress.gov.

- ^ Todd Sanders, Images of America: Jackson's North State Street (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009), 58 and 40.

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ a b "Old Capitol Museum | Mississippi Department of Archives & History". www.mdah.ms.gov. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12–13 Archived July 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001

- ^ Vicory, Justin. "Jackson libraries face an existential crisis that includes black mold. When will the city help?". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Dudley J. Hughes, Oil in the Deep South: A History of the Oil Business in Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, 1859–1945 (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1993), 67–86.

- ^ River and Harbor Act of 1930, July 3, 1930, ch. 847, 46 Stat. 918. Retrieved September 10, 2015. Watercases.org website Archived October 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dredging of Pearl Urged" (October 26, 1930) Clarion-Ledger. (Jackson), p.1

- ^ "Gold Coast" Archived July 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Blues website

- ^ Tribune, Daniel Egler, Chicago (February 8, 1990). "GAMBLING BOAT LAW GETS THOMPSON OK". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lyons, Amanda; Morgan, Will (May 1, 2018). "Patriots without a Country: Dutch Wings over Jackson" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ Samuel Howard Well (August 2018). "Jackson's Flying Dutchmen: The Significance of the Royal Netherlands Military Flying School". University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Remembering the fallen airmen of the Royal Netherlands Flying School in Mississippi". May 22, 2018. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "Mississippi – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ "Tougaloo 9". Civil Rights Movement Archive. Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ "Freedom Rides". Civil Rights Movement Archive. Archived from the original on July 7, 2010. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ "Jackson MS, Boycotts". Civil Rights Movement Archive. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ "Jackson Sit-in & Protests". Civil Rights Movement Archive. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ "Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement – History & Timeline, 1963 (Jan-June)". crmvet.org. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ Stout, David (January 23, 2001). "Byron De La Beckwith Dies; Killer of Medgar Evers Was 80 (Published 2001)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 6, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ History of Beth Israel, Jackson, Mississippi Archived October 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life website, History Department, Digital Archive, Mississippi, Jackson, Beth Israel. Retrieved August 17, 2008.

- ^ Edward Blum and Abigail Thernstrom, Executive Summary of the Bullock-Gaddie Expert Report on Mississippi, Apr 17, 2006 Archived April 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, American Enterprise Institute, Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ Eckl, K. (August 2, 2011). "The University of Mississippi: Pioneers in Transplant". Thoracic Surgery. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ (May 19, 1966). "Pearl Flood Project finished by June 1967". Jackson Daily News (Jackson).

- ^ Tim Spofford, Lynch Street: The May 1970 Slayings at Jackson State College, Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1988, pp. 17 and 19

- ^ Campbell, Don (July 27, 1982). "Governors hear call for drug task force". Clarion Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. p. 4A. - Clipping from Archived June 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Newspapers.com

- ^ Editors. (October 18, 1982) "Escalating war: plan beefs up drug enforcement". Clarion Ledger. (Jackson). p. 10A. Clipping from Newspapers.com

- ^ Eubank, Jay. (May 13, 1989) "More issues discussed during cliche-free round two". Clarion Ledger (Jackson)

- ^ ""Drugs, Law Enforcement, and Foreign Policy, a Report"." (PDF). United States Senate. Committee on Foreign Relations. Subcommittee on Terrorism, Narcotics, and International Operations. December 1988. pp. 278–295. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

Appendix. "Customs Report, Guy Penilton Owen, May 9, 1983".

- ^ Stuart Rockoff, "The Disappearing Southern Jew" Archived July 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, April 30, 2013, 'Southern and Jewish' blog, at My Jewish Learning (ISTL)

- ^ "Jackson Mississippi Tourism- City of Jackson Travel, MS Vacations, Event Planning". Visitjackson.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ "Mayor of U.S. city failing the hard test of crime prevention". The Taipei Times. Associated Press. July 27, 2006. Archived from the original on August 24, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. (December 2, 2008). "Drug kingpin, cohorts appeal convictions". Desoto Times. (Hernando, Miss.) Retrieved September 3, 2015. Desoto Times website Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mayor appoints sheriff who arrested him – twice – as police chief". USA Today. November 16, 2007. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ Sperling, Nicole (August 15, 2011). "March aims to draw attention to slaying of black Mississippi man". Sacramento Bee. Retrieved August 22, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Severson, Kimberly (August 22, 2011). "Killing of Black Man Prompts Reflection on Race in Mississippi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "James Craig Anderson's Death: FBI Investigates Fatal Rundown of Black Man in Mississippi". Associated Press. August 18, 2011. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ March 18, 2013: Severe Weather Event Archived October 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, NOAA

- ^ Insurers see more than 40,000 hailstorm claims Archived September 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Mississippi Business blog, April 3, 2013

- ^ "The Friendliest and Unfriendliest Cities in the U.S." Archived August 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, CN Traveler

- ^ Barnes, Dustin (April 24, 2014). "Mayor Tony Yarber Preaches Plans for Jackson". Clarion-Ledger.

- ^ "Jackson, Miss. Mayor-elect Chokwe Lumumba: I Plan to Build the "Most Radical City on the Planet"". Democracy Now!. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

- ^ Amir Vera; Jason Hanna; Nouran Salahieh (August 31, 2022). "The water crisis in Jackson, Mississippi, has gotten so bad, the city temporarily ran out of bottled water to give to residents". CNN. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Rojas, Rick (August 30, 2022). "Mississippi's Capital Loses Water as a Troubled System Faces a Fresh Crisis". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2022. Retrieved August 30, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Jackson city (part), Madison County, Mississippi". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Jackson city (part), Rankin County, Mississippi". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Jackson city, Mississippi". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2017.

- ^ https://casoilresource.lawr.ucdavis.edu/gmap/ Archived November 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine SoilWeb (Jackson MS)

- ^ Mississippi, University of (December 12, 2003). "The Geology of Mississippi" (PDF). University of Mississippi. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Harvey, E.J. et al. (April 1964). Ground-Water Resources of Hinds, Madison, and Rankin Counties, Miss. Bulletin 64-1. The state of Mississippi. Board of Water Commissioners. p. 3

- ^ a b "Station: Jackson INTL AP, MS". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Harvey, E.J. et al. (1964) op cit

- ^ a b c "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 30, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for JACKSON/THOMPSON FIELD MS 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Jackson city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- ^ "QuickFacts: Jackson city, Mississippi; United States". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ "1850 Census of Population: Mississippi" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Businesses Leave Downtown Jackson". April 19, 2003. Archived from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ^ Bisaha, Stephan; Chatlani, Shalina (November 13, 2022). "After decades of neglect, Jackson's Black business district is coming back to life". NPR. Archived from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Emily Wagster Pettus (September 1, 2022). "Mississippi capital's water disaster developed over decades". Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Jackson city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Jackson city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2022. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Jackson city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 10, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Census shows Mississippi lost population and diversified". AP NEWS. April 26, 2021. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Census shows US is diversifying, white population shrinking". AP NEWS. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007.

- ^ "2020 Income Characteristics". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Grocery store closes, creating food desert in area of Jackson". May 13, 2023. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Northside Drive Waffle House closes its doors". September 28, 2023. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Jackson councilman blames shoplifting for Food Depot closure". YouTube. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ LeMaster, C. J. (January 2, 2021). "Jackson closes out 2020 with the most homicides in city history, and a higher rate of killings than New Orleans, Memphis". Wlbt.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Estes, Hunter (January 15, 2021). "Jackson Homicide Rate Reaches Record High". Mississippi Center for Public Policy. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ LeMaster, C. J. (January 2, 2021). "Jackson closes out 2020 with the most homicides in city history, and a higher rate of killings than New Orleans, Memphis". Wlbt.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Summary crime reported by the Jackson Police Department". Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "'There's something wrong when Jackson's murder rate is higher than Atlanta,' official says". Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "So Jackson has a gang problem. What does that mean?". February 11, 2021. Archived from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved November 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Dixie pipeline: Mississippi major source of 'crime guns' on the streets of Chicago".

- ^ LeMaster, C. J. (January 7, 2023). "Analysis: For second straight year, Jackson's homicide rate ranks highest in U.S. among major cities". www.wlbt.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Mayor on Jackson Crime Center".

- ^ "JPD hopes to make progress with addressing staffing shortage through newest recruit class". August 2022. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Homicides drop by double digits for second year straight in Jackson, but rate of killings still ranks highest in nation". January 9, 2024. Archived from the original on February 15, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Mississippi governor announces new law enforcement operation to curb crime in capital city". Associated Press News. February 14, 2024. Archived from the original on February 15, 2024. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ "Top Employers in Jackson MSA". Jackson, MS. Archived from the original on December 2, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Jackson, Courtney Ann (August 12, 2022). "Amazon opens first robotics sortable center in Mississippi in Madison County". WLBT. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Moskowitz, P. E. (April 24, 2017). "Meet the Radical Workers' Cooperative Growing in the Heart of the Deep South". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ Franco, Cheree (October 2, 2019). "Building a Solidarity Economy in Jackson, Mississippi". The Indypendent. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ "Ballet Mississippi - Jackson's Premier Ballet Company". Ballet Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "CelticFest Mississippi". Celticfestms.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2002. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Crossroads Film Society - Jackson, Miss". Crossroadsfilmfestival.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "International Museum of Muslim Cultures". Muslimmuseum.org. Archived from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Joseph. "Blurring the lines between Light and Glass", Oxford Enterprise, Oxford, Mississippi, 18 April 2010.

- ^ "Mississippi Agriculture & Forestry Museum / National Agricultural Aviation Museum". Archived from the original on November 8, 2005. Retrieved November 9, 2005.

- ^ "MISSISSIPPI ARTS CENTER". January 16, 2009. Archived from the original on January 16, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "The Mississippi Chorus". Mschorus.org. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Waibel, Elizabeth. "Museum Needs Civil Rights Stories."". Jackson Free Press. January 27, 2012. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Mississippi Department of Archives and History". Archived from the original on November 30, 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Mississippi Heritage Trust". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Asociacion Hispana de Mississippi – Mississippi Hispanic Association". Mshispanicassociation.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Mississippi Metropolitan Ballet". Msmetroballet.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2004. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Mississippi Museum of Art". Msmuseumart.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2005. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Official City of Jackson, Mississippi Website - Municipal Art Gallery". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ Cannon, Austin. "New Stage Theatre - Mississippi's Professional Regional Theatre". newstagetheatre.com. Archived from the original on November 9, 2005. Retrieved November 10, 2005.

- ^ "City of Jackson, MS - Official Website - Davis Planetarium". thedavisplanetarium.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Official City of Jackson, Mississippi Website - Smith Robertson Museum". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- ^ "USA International Ballet Competition - IBC". usaibc.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^ "MPB : Mississippi Public Broadcasting". Mpbonline.org. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "The Final Hours: Out-going Mayor Tony Yarber reflects on time in office". Wjtv.com. June 30, 2017. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "City Council". City of Jackson, Mississippi. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Hinds County Archived October 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ "MDOC QUICK REFERENCE Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved May 21, 2010. "3794 Hwy 468 – Pearl, MS 39208"

- ^ "GARRISON COULD BE BACK IN JAIL SOON Archived October 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine." Biloxi Sun-Herald. February 15, 1995. C2 Coast and State. Retrieved September 24, 2011. "...County jail to the central Mississippi prison near Jackson in mid- 1994."

- ^ "Post Office Location – JACKSON Archived February 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- ^ "Jackson State Becomes the 4th Largest HBCU by Enrollment". Hbculifestyle.com. December 19, 2016. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Jackson State University | Mississippi Urban Research Center |". Jsums.edu. October 21, 2016. Archived from the original on December 20, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "List of 21 Mississippi Colleges and Universities". Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ About Jackson Public Schools Archived September 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Jackson.k12.ms.us (January 22, 2014). Retrieved on 2014-04-30.

- ^ Jackson State University Institutional Partners Archived September 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Jsums.edu. Retrieved on April 30, 2014.

- ^ Dreher, Arielle (November 15, 2017). "How Integration Failed in Jackson's Public Schools from 1969 to 2017". Jackson Free Press. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

In JPS, 99 percent of students are eligible for free and reduced lunch, as determined by federal poverty guidelines.

- ^ "Career Development Center: Home". Archived from the original on December 28, 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2005.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Hinds County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved July 1, 2021.

- ^ "attendance_zone.jpg." Hinds County School District. July 21, 2011. Retrieved on December 29, 2018. Compare with Hinds County district map.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Madison County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2021.