The House of Commons of Canada (French: Chambre des communes du Canada) is the lower house of the Parliament of Canada. Together with the Crown and the Senate of Canada, they comprise the bicameral legislature of Canada.

House of Commons of Canada Chambre des communes du Canada | |

|---|---|

| 44th Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | of the Parliament of Canada |

| History | |

| Founded | 1867 |

| Leadership | |

Justin Trudeau, Liberal since November 4, 2015 | |

Karina Gould, Liberal since July 26, 2023 | |

Andrew Scheer, Conservative since September 13, 2022 | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 338 |

| |

Political groups | His Majesty's Government

His Majesty's Loyal Opposition

Parties without official status

|

| Salary | CA$194,600 (sessional indemnity effective March 31, 2023)[1] |

| Elections | |

| First-past-the-post | |

First election | August 7 – September 20, 1867 |

Last election | September 20, 2021 |

Next election | On or before October 20, 2025 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| House of Commons Chamber West Block - Parliament Hill Ottawa, Ontario Canada | |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Constitution | |

| Constitution Act, 1867 | |

| Rules | |

| Standing Orders of the House of Commons (English, French) | |

The House of Commons is a democratically elected body whose members are known as members of Parliament (MPs). There have been up to 338 MPs since the most recent electoral district redistribution for the 2015 federal election, which saw the addition of 30 seats.[2][3][4][5] Members are elected by simple plurality ("first-past-the-post" system) in each of the country's electoral districts, which are colloquially known as ridings.[6] MPs may hold office until Parliament is dissolved and serve for constitutionally limited terms of up to five years after an election. Historically, however, terms have ended before their expiry and the sitting government has typically dissolved parliament within four years of an election according to a long-standing convention. In any case, an act of Parliament now limits each term to four years. Seats in the House of Commons are distributed roughly in proportion to the population of each province and territory. However, some ridings are more populous than others, and the Canadian constitution contains provisions regarding provincial representation. As a result, there is some interprovincial and regional malapportionment relative to the population.

The British North America Act 1867 (now called the Constitution Act, 1867) created the House of Commons, modelling it on the British House of Commons. The lower of the two houses making up the parliament, the House of Commons, in practice holds far more power than the upper house, the Senate. Although the approval of both chambers is necessary for legislation to become law, the Senate only occasionally amends bills passed by the House of Commons and rarely rejects them. Moreover, the Cabinet is responsible primarily to the House of Commons. The government stays in office only so long as they retain the support, or "confidence", of the lower house.

The House of Commons meets in a temporary chamber in the West Block of the parliament buildings on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, while the Centre Block, which houses the traditional Commons chamber, undergoes renovation.

Name

editThe term derives from the Anglo-Norman word communes, referring to the geographic and collective "communities" of their parliamentary representatives and not the third estate, the commonality.[7] This distinction is made clear in the official French name of the body, Chambre des communes. Canada and the United Kingdom remain the only countries to use the name "House of Commons" for a lower house of parliament. The body's formal name is: The Honourable the Commons of Canada in Parliament assembled (French: l’Honorable Chambre des communes du Canada, en Parlement assemblée[8])[9]

History

editThe House of Commons came into existence in 1867, when the British Parliament passed the British North America Act 1867, uniting the Province of Canada (which was divided into Quebec and Ontario), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick into a single federation called Canada. The new Parliament of Canada consisted of the monarch (represented by the governor general, who also represented the Colonial Office), the Senate and the House of Commons. The Parliament of Canada was based on the Westminster model (that is, the model of the Parliament of the United Kingdom). Unlike the UK Parliament, the powers of the Parliament of Canada were limited in that other powers were assigned exclusively to the provincial legislatures. The Parliament of Canada also remained subordinate to the British Parliament, the supreme legislative authority for the entire British Empire. Greater autonomy was granted by the Statute of Westminster 1931,[10] after which new acts of the British Parliament did not apply to Canada, with some exceptions. These exceptions were removed by the Canada Act 1982.[11]

From 1867, the Commons met in the chamber previously used by the Legislative Assembly of Canada until the building was destroyed by fire in 1916. It relocated to the amphitheatre of the Victoria Memorial Museum — what is today the Canadian Museum of Nature, where it met until 1922. Until the end of 2018, the Commons sat in the Centre Block chamber. Starting with the final sitting before the 2019 federal election, the Commons sits in a temporary chamber in the West Block until at least 2028, while renovations are undertaken in the Centre Block of Parliament.

Members and electoral districts

editThe House of Commons has 338 members, each of whom represents a single electoral district (also called a riding). The constitution specifies a basic minimum of 295 electoral districts, but additional seats are allocated according to various clauses. Seats are distributed among the provinces in proportion to population, as determined by each decennial census, subject to the following exceptions made by the constitution. Firstly, the "senatorial clause" guarantees that each province will have at least as many MPs as senators.[12] Secondly, the "grandfather clause" guarantees each province has at least as many Members of Parliament now as it had in 1985.[12] (This was amended in 2021 to be the number of members in the 43rd Canadian Parliament.)

As a result of these clauses, smaller provinces and territories that have experienced a relative decline in population have become over-represented in the House. Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta are under-represented in proportion to their populations, while Quebec's representation is close to the national average. The other six provinces (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador) are over-represented. Boundary commissions, appointed by the federal government for each province, have the task of drawing the boundaries of the electoral districts in each province. Territorial representation is independent of the population; each territory is entitled to only one seat. The electoral quotient was defined by legislation as 111,166 for the redistribution of seats after the 2011 census and is adjusted following each decennial census by multiplying it by the average of the percentage of population change of each province since the previous decennial census.[13] The population of the province is then divided by the electoral quotient to equal the base provincial-seat allocation.[12][14] The "special clauses" are then applied to increase the number of seats for certain provinces, bringing the total number of seats (with the three seats for the territories) to 338.[12]

The most recent redistribution of seats occurred subsequent to the 2011 census.[12] The Fair Representation Act was passed and given royal assent on December 16, 2011, and effectively allocated fifteen additional seats to Ontario, six new seats each to Alberta and British Columbia, and three more to Quebec.[5][13]

A new redistribution began in October 2021 subsequent to the 2021 census, it is expected to go into effect at the earliest for any federal election called after April 2024.[15] After initial controversy that Quebec would lose a seat in the redistribution under the existing representation formula established by the Fair Representation Act, the Preserving Provincial Representation in the House of Commons Act was passed and given royal assent on June 23, 2022, and effectively allocated three additional seats to Alberta and one new seat each to Ontario and British Columbia.[16][17]

The following tables summarize representation in the House of Commons by province and territory:[18]

| Province | Population (2021 census) |

Total seats allocated 2012 redistribution |

Electoral quotient (average population per electoral district) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario | 14,223,942 | 121 | 117,553 |

| Quebec | 8,501,833 | 78 | 108,998 |

| British Columbia | 5,000,879 | 42 | 119,069 |

| Alberta | 4,262,635 | 34 | 125,372 |

| Manitoba | 1,342,153 | 14 | 95,868 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,132,505 | 14 | 80,893 |

| Nova Scotia | 969,383 | 11 | 88,126 |

| New Brunswick | 775,610 | 10 | 77,561 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 510,550 | 7 | 72,936 |

| Prince Edward Island | 154,331 | 4 | 38,583 |

| Total for provinces | 36,873,821 | 335 | 110,071 |

| Northwest Territories | 41,070 | 1 | 41,070 |

| Yukon | 40,232 | 1 | 40,232 |

| Nunavut | 36,858 | 1 | 36,858 |

| Total for territories | 118,160 | 3 | 39,387 |

| National total | 36,991,981 | 338 | 109,444 |

Elections

editGeneral elections occur whenever parliament is dissolved by the governor general on the monarch's behalf. The timing of the dissolution has historically been chosen by the Prime minister. The Constitution Act, 1867, provides that a parliament last no longer than five years. Canadian election law requires that elections must be held on the third Monday in October in the fourth year after the last election, subject to the discretion of the Crown.[19] Campaigns must be at least 36 days long. Candidates are usually nominated by political parties. A candidate can run independently, although it is rare for such a candidate to win. Most successful independent candidates have been incumbents who were expelled from their political parties (for example, John Nunziata in 1997 or Jody Wilson-Raybould in 2019) or who failed to win their parties' nomination (for example, Chuck Cadman in 2004). Most Canadian candidates are chosen in meetings called by their party's local association. In practice, the candidate who signs up the most local party members generally wins the nomination.

To run for a seat in the house, candidates must file nomination papers bearing the signatures of at least 50 or 100 constituents (depending on the size of the electoral district). Each electoral district returns one member using the first-past-the-post electoral system, under which the candidate with a plurality of votes wins. To vote, one must be a citizen of Canada and at least eighteen years of age. Declining the ballot, which is possible in several provinces, is not an option under current federal regulations.[20]

Once elected, a member of Parliament normally continues to serve until the next dissolution of parliament. If a member dies, resigns, or ceases to be qualified, their seat falls vacant. It is also possible for the House of Commons to expel a member, but this power is only exercised when the member has engaged in serious misconduct or criminal activity. Formerly, MPs appointed to the cabinet were expected to resign their seats, though this practice ceased in 1931. In each case, a vacancy may be filled by a by-election in the appropriate electoral district. The first-past-the-post system is used in by-elections, as in general elections.[21]

Prerequisites

editThe term member of Parliament is usually used only to refer to members of the House of Commons, even though the Senate is also a part of Parliament. Members of the House of Commons may use the post-nominal letters "MP". The annual salary of each MP, as of April 2021,[update] was $185,800;[22] members may receive additional salaries in right of other offices they hold (for instance, the speakership). MPs rank immediately below senators in the order of precedence.

Qualifications

editUnder the Constitution Act, 1867, Parliament is empowered to determine the qualifications of members of the House of Commons. The present qualifications are outlined in the Canada Elections Act, which was passed in 2000. Under the Act, individuals must be eligible voters as of the day of nomination, to stand as a candidate. Thus, minors and individuals who are not citizens of Canada are not allowed to become candidates. The Canada Elections Act also bars prisoners from standing for election (although they may vote). Moreover, individuals found guilty of election-related crimes are prohibited from becoming members for five years (in some cases, seven years) after conviction.

The Act also prohibits certain officials from standing for the House of Commons. These officers include members of provincial and territorial legislatures (although this was not always the case), sheriffs, crown attorneys, most judges, and election officers. The chief electoral officer (the head of Elections Canada, the federal agency responsible for conducting elections) is prohibited not only from standing as candidate but also from voting. Finally, under the Constitution Act, 1867, a member of the Senate may not also become a member of the House of Commons and MPs must give up their seats when appointed to the Senate or the bench.

Officers and symbols

editThe House of Commons elects a presiding officer, known as the speaker,[2] at the beginning of each new parliamentary term, and also whenever a vacancy arises. Formerly, the prime minister determined who would serve as speaker. Although the House voted on the matter, the voting constituted a mere formality. Since 1986, however, the House has elected speakers by secret ballot. The speaker is assisted by a deputy speaker, who also holds the title of chair of Committees of the Whole. Two other deputies—the deputy chair of Committees of the Whole and the assistant deputy chair of Committees of the Whole—also preside. The duties of presiding over the House are divided between the four officers aforementioned; however, the speaker usually presides over Question Period and over the most important debates.

The speaker controls debates by calling on members to speak. If a member believes that a rule (or standing order) has been breached, they may raise a "point of order", on which the speaker makes a ruling that is not subject to any debate or appeal. The speaker may also discipline members who fail to observe the rules of the House. When presiding, the speaker must remain impartial. The speaker also oversees the administration of the House and is chair of the Board of Internal Economy, the governing body for the House of Commons. The current speaker of the House of Commons is Greg Fergus.

The member of the Government responsible for steering legislation through the House is leader of the Government in the House of Commons. The government house leader (as they are more commonly known) is a member of Parliament selected by the prime minister and holds cabinet rank. The leader manages the schedule of the House of Commons and attempts to secure the Opposition's support for the Government's legislative agenda.

Officers of the House who are not members include the clerk of the House of Commons, the deputy clerk, the law clerk and parliamentary counsel, and several other clerks. These officers advise the speaker and members on the rules and procedure of the House in addition to exercising senior management functions within the House administration. Another important officer is the sergeant-at-arms, whose duties include the maintenance of order and security on the House's premises and inside the buildings of the parliamentary precinct. (The Royal Canadian Mounted Police patrol Parliament Hill but are not allowed into the buildings unless asked by the speaker). The sergeant-at-arms also carries the ceremonial mace, a symbol of the authority of the Crown and the House of Commons, into the House each sitting. The House is also staffed by parliamentary pages, who carry messages to the members in the chamber and otherwise provide assistance to the House.

The Commons' mace has the shape of a medieval mace which was used as a weapon, but in brass and ornate in detail and symbolism. At its bulbous head is a replica of the Imperial State Crown;[citation needed] the choice of this crown for the Commons' mace differentiates it from the Senate's mace, which has St. Edward's Crown[citation needed] at its apex. The Commons mace is placed upon the table in front of the speaker for the duration of the sitting with the crown pointing towards the prime minister and the other cabinet ministers, who advise the monarch and governor general and are accountable to this chamber (in the Senate chamber, the mace points towards the throne, where the king has the right to sit himself).

Carved above the speaker's chair is the royal arms of the United Kingdom. This chair was a gift from the United Kingdom Branch of the Empire Parliamentary Association in 1921, to replace the chair that was destroyed by the fire of 1916, and was a replica of the chair in the British House of Commons at the time. These arms at its apex were considered the royal arms for general purposes throughout the British Empire at the time. Since 1931, however, Canada has been an independent country and the Canadian coat of arms are now understood to be the royal arms of the monarch. Escutcheons of the same original royal arms can be found on each side of the speaker's chair held by a lion and a unicorn.

In response to a campaign by Bruce Hicks for the Canadianization of symbols of royal authority and to advance the identity of parliamentary institutions,[23] a proposal that was supported by speakers of the House of Commons John Fraser and Gilbert Parent, a Commons committee was eventually struck following a motion by MP Derek Lee, before which Hicks and Robert Watt, the first chief herald of Canada, was called as the only two expert witnesses, though Senator Serge Joyal joined the committee on behalf of the Senate. Commons' speaker Peter Milliken then asked the governor general to authorize such a symbol. In the United Kingdom, the House of Commons and the House of Lords use the royal badge of the portcullis, in green and red respectively,[citation needed] to represent those institutions and to distinguish them from the government, the courts and the monarch. The Canadian Heraldic Authority on April 15, 2008, granted the House of Commons, as an institution, a badge consisting of the chamber's mace (as described above) behind the escutcheon of the shield of the royal arms of Canada (representing the monarch, in whose name the House of Commons deliberates).[24]

Procedure

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

Like the Senate, the House of Commons meets on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. The Commons Chamber is modestly decorated in green, in contrast with the more lavishly furnished red Senate Chamber. The arrangement is similar to the design of the Chamber of the British House of Commons.[25] The seats are evenly divided between both sides of the Chamber, three sword-lengths apart (about three metres).[26] The speaker's chair (which can be adjusted for height) is at the north end of the Chamber. In front of it is the Table of the House, on which rests the ceremonial mace. Various "table officers"—clerks and other officials—sit at the table, ready to advise the speaker on procedure when necessary. Members of the Government sit on the benches on the speaker's right, while members of the Opposition occupy the benches on the speaker's left. Government ministers sit around the prime minister, who is traditionally assigned the 11th seat in the front row on the speaker's right-hand side. The leader of the Official Opposition sits directly across from the prime minister and is surrounded by a Shadow Cabinet or critics for the government portfolios. The remaining party leaders sit in the front rows. Other members of Parliament who do not hold any kind of special responsibilities are known as "backbenchers".

The House usually sits Monday to Friday from late January to mid-June and from mid-September to mid-December according to an established calendar, though it can modify the calendar if additional or fewer sittings are required.[2] During these periods, the House generally rises for one week per month to allow members to work in their constituencies. Sittings of the House are open to the public. Proceedings are broadcast over cable and satellite television and over live streaming video on the Internet by CPAC owned by a consortium of Canadian cable companies. They are also recorded in text form in print and online in Hansard, the official report of parliamentary debates.

The Constitution Act, 1867 establishes a quorum of twenty members (including the member presiding) for the House of Commons. Any member may request a count of the members to ascertain the presence of a quorum; if however, the speaker feels that at least twenty members are clearly in the Chamber, the request may be denied. If a count does occur, and reveals that fewer than twenty members are present, the speaker orders bells to be rung, so that other members on the parliamentary precincts may come to the Chamber. If, after a second count, a quorum is still not present, the speaker must adjourn the House until the next sitting day.

During debates, members may only speak if called upon by the speaker (or, as is most often the case, the deputy presiding). The speaker is responsible for ensuring that members of all parties have an opportunity to be heard. The speaker also determines who is to speak if two or more members rise simultaneously, but the decision may be altered by the House. Motions must be moved by one member and seconded by another before debate may begin. Some motions, however, are non-debatable.

Speeches[2] may be made in either of Canada's official languages (English and French), and it is customary for bilingual members of parliament to respond to these in the same language they were made in. It is common for bilingual MPs to switch between languages during speeches. Members must address their speeches to the presiding officer, not the House, using the words "Mr. Speaker" (French: Monsieur le Président) or "Madam Speaker" (French: Madame la Présidente). Other members must be referred to in the third person. Traditionally, members do not refer to each other by name, but by constituency or cabinet post, using forms such as "the honourable member for [electoral district]" or "the minister of..." Members' names are routinely used only during roll call votes, in which members stand and are named to have their vote recorded; at that point they are referred to by title (Ms. or mister for Anglophones and madame, mademoiselle, or monsieur for Francophones) and last name, except where members have the same or similar last names, at which point they would be listed by their name and riding ("M. Massé, Avignon—La Mitis—Matane—Matapédia; Mr. Masse, Windsor West....).

No member may speak more than once on the same question (except that the mover of a motion is entitled to make one speech at the beginning of the debate and another at the end). Moreover, tediously repetitive or irrelevant remarks are prohibited, as are written remarks read into the record (although this behaviour is creeping into the modern debate). The speaker may order a member making such remarks to cease speaking. The Standing Orders of the House of Commons prescribe time limits for speeches. The limits depend on the nature of the motion but are most commonly between ten and twenty minutes. However, under certain circumstances, the prime minister, the Opposition leader, and others are entitled to make longer speeches. The debate may be further restricted by the passage of "time allocation" motions. Alternatively, the House may end debate more quickly by passing a motion for "closure".

When the debate concludes, the motion in question is put to a vote. The House first votes by voice vote; the presiding officer puts the question, and members respond either "yea" (in favour of the motion) or "nay" (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote, but five or more members may challenge the assessment, thereby forcing a recorded vote (known as a division, although, in fact, the House does not divide for votes the way the British House of Commons does). First, members in favour of the motion rise, so that the clerks may record their names and votes. Then, the same procedure is repeated for members who oppose the motion. There are no formal means for recording an abstention, though a member may informally abstain by remaining seated during the division. If there is an equality of votes, the speaker has a casting vote.

The outcome of most votes is largely known beforehand since political parties normally instruct members on how to vote. A party normally entrusts some members of Parliament, known as whips, with the task of ensuring that all party members vote as desired. Members of Parliament do not tend to vote against such instructions since those who do so are unlikely to reach higher political ranks in their parties. Errant members may be deselected as official party candidates during future elections, and, in serious cases, may be expelled from their parties outright. Thus, the independence of members of Parliament tends to be extremely low, and "backbench rebellions" by members discontent with their party's policies are rare. In some circumstances, however, parties announce "free votes", allowing members to vote as they please. This may be done on moral issues and is routine on private members' bills.

Committees

editThe Parliament of Canada uses committees for a variety of purposes. Committees consider bills in detail and may make amendments. Other committees scrutinize various Government agencies and ministries.

Potentially, the largest of the Commons committees are the Committees of the Whole, which, as the name suggests, consist of all the members of the House. A Committee of the Whole meets in the Chamber of the House but proceeds under slightly modified rules of debate. (For example, a member may make more than one speech on a motion in a Committee of the Whole, but not during a normal session of the House.) Instead of the speaker, the chair, deputy chair, or assistant deputy chair presides. The House resolves itself into a Committee of the Whole to discuss appropriation bills, and sometimes for other legislation.

The House of Commons also has several standing committees, each of which has responsibility for a particular area of government (for example, finance or transport). These committees oversee the relevant government departments, may hold hearings and collect evidence on governmental operations and review departmental spending plans. Standing committees may also consider and amend bills. Standing committees consist of between sixteen and eighteen members each, and elect their chairs.

Some bills are considered by legislative committees, each of which consists of up to fifteen members. The membership of each legislative committee roughly reflects the strength of the parties in the whole House. A legislative committee is appointed on an ad hoc basis to study and amend a specific bill. Also, the chair of a legislative committee is not elected by the members of the committee but is instead appointed by the speaker, normally from among the speaker's deputies. Most bills, however, are referred to standing committees rather than legislative committees.

The House may also create ad hoc committees to study matters other than bills. Such committees are known as special committees. Each such body, like a legislative committee, may consist of no more than fifteen members. Other committees include joint committees, which include both members of the House of Commons and senators; such committees may hold hearings and oversee government, but do not revise legislation.

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development

- Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics

- Agriculture and Agri-Food

- Canadian Heritage

- Citizenship and Immigration

- Electoral Reform

- Environment and Sustainable Development

- Finance

- Fisheries and Oceans

- Foreign Affairs and International Development

- Government Operations and Estimates

- Health

- Human Resources, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities

- Industry, Science and Technology

- International Trade

- Justice and Human Rights

- Liaison Committee

- National Defence

- Natural Resources

- Official Languages

- Procedure and House Affairs

- Public Accounts

- Public Safety and National Security

- Status of Women

- Transport, Infrastructure and Communities

- Veterans Affairs

Legislative functions

editAlthough legislation may be introduced in either chamber, most bills originate in the House of Commons.

In conformity with the British model, the Lower House alone is authorized to originate bills imposing taxes or appropriating public funds. This restriction on the power of the Senate is not merely a matter of convention, but is explicitly stated in the Constitution Act, 1867. Otherwise, the power of the two Houses of Parliament is theoretically equal; the approval of each is necessary for a bill's passage.

In practice, however, the House of Commons is the dominant chamber of Parliament, with the Senate very rarely exercising its powers in a way that opposes the will of the democratically elected chamber. The last major bill defeated in the Senate came in 2010, when a bill passed by the Commons concerning climate change was rejected in the Senate.[27]

A clause in the Constitution Act, 1867 permits the governor general (with the approval of the monarch) to appoint up to eight extra senators to resolve a deadlock between the two houses. The clause was invoked only once, in 1990, when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney advised the appointment of an additional eight senators to secure the Senate's approval for the Goods and Services Tax.

Relationship with the Government of Canada

editAs a Westminster democracy, the Government of Canada, or more specifically the Governor-in-Council, exercising the executive power on behalf of the prime minister and Cabinet, enjoys a complementary relationship with the House of Commons—similar to the UK model, and in contrast to the US model of separation of powers. Though it does not formally elect the prime minister, the House of Commons indirectly controls who becomes prime minister. By convention, the prime minister is answerable to and must maintain the support of, the House of Commons. Thus, whenever the office of prime minister falls vacant, the governor general has the duty of appointing the person most likely to command the support of the House—normally the leader of the largest party in the lower house, although the system allows a coalition of two or more parties. This has not happened in the Canadian federal parliament but has occurred in Canadian provinces. The leader of the second-largest party (or in the case of a coalition, the largest party out of government) usually becomes the leader of the Official Opposition. Moreover, the prime minister is, by unwritten convention, a member of the House of Commons, rather than of the Senate. Only two prime ministers governed from the Senate: Sir John Abbott (1891–1892) and Sir Mackenzie Bowell (1894–1896). Both men got the job following the death of a prime minister and did not contest elections.

The prime minister stays in office by retaining the confidence of the House of Commons. The lower house may indicate its lack of support for the government by rejecting a motion of confidence, or by passing a motion of no confidence. Important bills that form a part of the government's agenda are generally considered matters of confidence, as is any taxation or spending bill and the annual budget. When a government has lost the confidence of the House of Commons, the prime minister is obliged to either resign or request the governor general to dissolve parliament, thereby precipitating a general election. The governor general may theoretically refuse to dissolve parliament, thereby forcing the prime minister to resign. The last instance of a governor general refusing to grant a dissolution was in 1926.

Except when compelled to request a dissolution by an adverse vote on a confidence issue, the prime minister is allowed to choose the timing of dissolutions, and consequently the timing of general elections. The time chosen reflects political considerations, and is generally most opportune for the prime minister's party. However, no parliamentary term can last for more than five years from the first sitting of Parliament; a dissolution is automatic upon the expiry of this period. Normally, Parliaments do not last for full five-year terms; prime ministers typically ask for dissolutions after about three or four years. In 2006, the Harper government introduced a bill to set fixed election dates every four years, although snap elections are still permitted. The bill was approved by Parliament and has now become law.

Whatever the reason—the expiry of parliament's five-year term, the choice of the prime minister, or a government defeat in the House of Commons—a dissolution is followed by general elections. If the prime minister's party retains its majority in the House of Commons, then the prime minister may remain in power. On the other hand, if their party has lost its majority, the prime minister may resign or may attempt to stay in power by winning support from members of other parties. A prime minister may resign even if he or she is not defeated at the polls (for example, for personal health reasons); in such a case, the new leader of the outgoing prime minister's party becomes prime minister.

The House of Commons scrutinizes the ministers of the Crown through Question Period, a daily forty-five-minute period during which members have the opportunity to ask questions of the prime minister and other Cabinet ministers. Questions must relate to the responding minister's official government activities, not to their activities as a party leader or as a private Member of Parliament. Members may also question committee chairmen on the work of their respective committees. Members of each party are entitled to the number of questions proportional to the party caucus' strength in the house. In addition to questions asked orally during Question Period, Members of Parliament may also make inquiries in writing.

In times where there is a majority government, the House of Commons' scrutiny of the government is weak. Since elections use the first-past-the-post electoral system, the governing party tends to enjoy a large majority in the Commons; there is often limited need to compromise with other parties. (Minority governments, however, are not uncommon.) Modern Canadian political parties are so tightly organized that they leave relatively little room for free action by their MPs. In many cases, MPs may be expelled from their parties for voting against the instructions of party leaders. As well, the major parties require candidates' nominations to be signed by party leaders, thus giving the leaders the power to, effectively, end a politician's career.[citation needed] Thus, defeats of majority governments on issues of confidence are very rare. Paul Martin's Liberal minority government lost a vote of no confidence in 2005; the last time this had occurred was in 1979, when Joe Clark's Progressive Conservative minority government was defeated after a term of just six months.

Current composition

edit| Party[28] | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| Liberal | 153 | |

| Conservative | 119 | |

| Bloc Québécois | 33 | |

| New Democratic | 25 | |

| Green | 2 | |

| Independent | 4 | |

| Vacant | 2 | |

| Total | 338 | |

- Notes

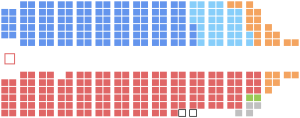

Seating plan

editSeating plan for the current House of Commons:[29]

- Party leaders are italicized. Bold indicates cabinet minister.

Chamber design

editThe current and original Canadian House of Commons chamber was influenced by the British House of Commons rectangular layout and that of the original St Stephen's Chapel in the Palace of Westminster.[30] The difference from the British layout is with the use of individual chairs and tables for members, absent in the British Commons' design.

With the exception of the legislatures in Nunavut (circular seating), the Northwest Territories (circular seating), and Manitoba (U-shaped seating), all other Canadian provincial legislatures share the common design of the Canadian House of Commons.

The Department of Public Works and Government Services undertook work during the 41st Parliament to determine how the seating arrangement could be modified to accommodate the additional 30 seats added in the 2015 election. Ultimately, new "theatre" seats were designed, with five seats in a row at one desk, the seats pulling down for use. Such seat sets now form almost the entire length of the last two rows on each side of the chamber.[31]

Renovations

editThe current chamber is currently undergoing an estimated decade-long restoration and renovation, which began in December 2018.[32] Parliamentarians have relocated to the courtyard of the 159-year-old West Block which also underwent seven years of renovations and repairs to get ready for the move.[32][33] Prime Minister Justin Trudeau marked the closing of the Centre Block on December 12, 2018.[34] The final sittings of both the House of Commons and the Senate in Centre Block took place on December 13, 2018.

See also

edit- Parties and elections

- Elections Canada

- List of Canadian federal electoral districts

- List of Canadian federal general elections

- List of political parties in Canada

- List of political parties in Canada by representation

- Parliaments and members

Offices

editOff Parliament Hill, MPs have some offices at the Justice Building or Confederation Building down Wellington Street near the Supreme Court.

References

edit- ^ "Indemnities, Salaries and Allowances". Parlinfo. Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Guide to the Canadian House of Commons (PDF). House of Commons of Canada. 2009. ISBN 978-0-662-68678-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 20, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Members of the House of Commons – Current List – By Name". Parliament of Canada. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on September 25, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ "Members of Parliament". Parliament of Canada. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Thandi Fletcher (December 16, 2011). "Crowded House: Parliament gets cozier as 30 seats added". Canada.com. Postmedia News. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ "Elections Canada On-Line". Electoral Insight. November 21, 2006. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ^ A. F. Pollard, The Evolution of Parliament (Longmans, 1920), 107–08.

- ^ Marleau, Robert; Montpetit, Camille (2000). "22. Les pétitions d'intérêt public". In Chambre des communes (ed.). La procédure et les usages de la Chambre des communes. Chambre des communes. p. 1152. ISBN 9782894613771..

- ^ Gemmill, John Alexander (1883). The Canadian Parliamentary Companion. Ottawa: Citizen Print. and Publishing Company. p. 36. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Statute of Westminster, 1931 – History – Intergovernmental Affairs". Privy Council Office. Government of Canada. September 13, 2007. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ "The Constitution Act, 1982". The Solon Law Archive. W.F.M. Archived from the original on October 21, 2009. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Department of Justice (Canada) (November 2, 2009). "Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982". Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ a b "41st Parliament, 1st Session, Bill C-20". Parliament of Canada. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ Jackson, Robert J.; Jackson, Doreen (2008). Politics in Canada: Culture, Institutions, Behaviour and Public Policy. Toronto: Prentice Hall. p. 438. ISBN 9780132069380.

- ^ Canada, Elections (August 12, 2021). "Timeline for the Redistribution of Federal Electoral Districts". www.elections.ca. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Liberals table bill to protect number of Quebec seats in Parliament, a condition of deal with NDP". National Post. March 24, 2022. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ "An Act to amend the Constitution Act, 1867 (electoral representation)". Parliament of Canada. March 24, 2022. Archived from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Elections Canada (2012). "House of Commons Seat Allocation by Province 2012 to 2022". Archived from the original on January 3, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- ^ Canada Elections Act, Section 56.1(2) Archived September 24, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Humphreys, Adrian (November 12, 2018). "Unhappy voter loses bid to officially vote 'none of the above' in federal election". National Post. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ "The Electoral System of Canada : The Political System". Elections Canada. Archived from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ "Indemnities, Salaries and Allowances". Library of Parliament. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- ^ Hicks, Bruce. A 'Call to Arms' for the Canadian Parliament" (Canadian Parliamentary Review 23:4).

- ^ Canadian Heraldic Authority. "Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada > House of Commons of Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ "House of Commons Green" (PDF). parliament.uk. March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 11, 2009.

- ^ "Tuesday, June 20, 1995 (222)". House of Commons Hansard. Parliament of Canada. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ^ "Senate vote to kill Climate Act disrespects Canadians and democracy". davidsuzuki.org. October 19, 2010. Archived from the original on May 3, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Party Standings in the House of Commons". parl.gc.ca. Archived from the original on May 2, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ "House of Commons Seating Plan - Members of Parliament - House of Commons of Canada". Archived from the original on November 5, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ The Commons Chamber in the 16th Century – UK Parliament Archived November 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Parliament.uk (April 21, 2010). Retrieved on April 12, 2014.

- ^ O'Mally, Kady. "House of Commons a no-go zone for tourists this summer". CBC.ca. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ a b "The replacement House of Commons is just about ready". cbc.ca. November 9, 2018. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ Grenier, Eric (December 12, 2018). "Trudeau, Scheer spar for what might be the last time in Parliament's Centre Block". cbc.ca. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ @CanadianPM (December 12, 2018). "Prime Minister Justin Trudeau marks the closing of Centre Block today in the House of Commons" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

Bibliography

edit- David E. Smith (2007). The people's House of Commons: theories of democracy in contention. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9465-0.

- Department of Justice. (2004). Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982. Archived March 21, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- Dawson, W F (1962). Procedure in the Canadian House of Commons. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802070494. OCLC 502155. Also under OCLC 252298936.

- House of Commons Table Research Branch. (2006). Compendium of Procedure. Archived February 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- The Parliament of Canada. Official Website. Archived May 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Canada's House of Commons from The Canadian Encyclopedia Archived September 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- About parliament - House of Commons, Inter-Parliamentary Union

External links

edit- Official website

- Media related to House of Commons of Canada at Wikimedia Commons

- House of Commons of Canada at Wikinews