Friulian (/friˈuːliən/ free-OO-lee-ən) or Friulan (natively ⓘ or marilenghe; Italian: friulano; Austrian German: Furlanisch; Slovene: furlanščina) is a Romance language belonging to the Rhaeto-Romance family, spoken in the Friuli region of northeastern Italy. Friulian has around 600,000 speakers, the vast majority of whom also speak Italian. It is sometimes called Eastern Ladin since it shares the same roots as Ladin, but over the centuries, it has diverged under the influence of surrounding languages, including German, Italian, Venetian, and Slovene. Documents in Friulian are attested from the 11th century and poetry and literature date as far back as 1300. By the 20th century, there was a revival of interest in the language.

| Friulian | |

|---|---|

| furlan | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Friuli |

| Ethnicity | Friulians |

Native speakers | Regular speakers: 420,000 (2014)[1] Total: 600,000 (2014)[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin (Friulian alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | Agjenzie regjonâl pe lenghe furlane [2] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | fur |

| ISO 639-3 | fur |

| Glottolog | friu1240 |

| ELP | Friulian |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAA-m |

| |

History edit

A question that causes many debates is the influence of the Latin spoken in Aquileia and surrounding areas. Some claim that it had peculiar features that later passed into Friulian. Epigraphs and inscriptions from that period show some variants if compared to the standard Latin language, but most of them are common to other areas of the Roman Empire. Often, it is cited that Fortunatianus, the bishop of Aquileia c. 342–357 AD, wrote a commentary to the Gospel in sermo rusticus (the common/rustic language), which, therefore, would have been quite divergent from the standard Latin of administration.[3] The text itself did not survive so its language cannot be examined, but its attested existence testifies to a shift of languages while, for example, other important communities of Northern Italy were still speaking Latin. The language spoken before the arrival of the Romans in 181 BC was of Celtic origin since the inhabitants belonged to the Carni, a Celtic population.[4] In modern Friulian, the words of Celtic origins are many (terms referring to mountains, woods, plants, animals, inter alia) and much influence of the original population is shown in toponyms (names of villages with -acco, -icco).[5] Even influences from the Lombardic language — Friuli was one of their strongholds — are very frequent. In a similar manner, there are unique connections to the modern, nearby Lombard language.

In Friulian, there is also a plethora of words of German, Slovenian and Venetian origin. From that evidence, scholars today agree that the formation of Friulian dates back to circa 1000 AD, at the same time as other dialects derived from Latin (see Vulgar Latin). The first written records of Friulian have been found in administrative acts of the 13th century, but the documents became more frequent in the following century, when literary works also emerged (Frammenti letterari for example). The main centre at that time was Cividale. The Friulian language has never acquired primary official status: legal statutes were first written in Latin, then in Venetian and finally in Italian.

The "Ladin Question" edit

The idea of unity among Ladin, Romansh and Friulian comes from the Italian historical linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli, who was born in Gorizia. In 1871, he presented his theory that these three languages are part of one family, which in the past stretched from Switzerland to Muggia and perhaps also Istria. The three languages are the only survivors of this family and all developed differently. Friulian was much less influenced by German. The scholar Francescato claimed subsequently that until the 14th century, the Venetian language shared many phonetic features with Friulian and Ladin and so he thought that Friulian was a much more conservative language. Many features that Ascoli thought were peculiar to the Rhaeto-Romance languages can, in fact, be found in other languages of Northern Italy.

Areas edit

Italy edit

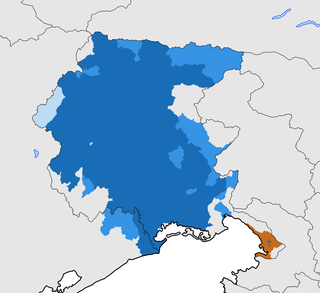

Today, Friulian is spoken in the province of Udine, including the area of the Carnia Alps, but as well throughout the province of Pordenone, in half of the province of Gorizia, and in the eastern part of the province of Venice. In the past, the language borders were wider since in Trieste and Muggia, local variants of Friulian were spoken. The main document about the dialect of Trieste, or tergestino, is "Dialoghi piacevoli in dialetto vernacolo triestino", published by G. Mainati in 1828.

World edit

Friuli was, until the 1960s, an area of deep poverty, causing a large number of Friulian speakers to emigrate. Most went to France, Belgium, and Switzerland or outside Europe, to Canada, Mexico, Australia, Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, the United States, and South Africa. In those countries, there are associations of Friulian immigrants (called Fogolâr furlan) that try to protect their traditions and language.

Literature edit

This section is missing information about Examples and english translation of 13th and 14th century texts. (May 2018) |

The first texts in Friulian date back to the 13th century and are mainly commercial or juridical acts. The examples show that Friulian was used together with Latin, which was still the administrative language. The main examples of literature that have survived (much from this period has been lost) are poems from the 14th century and are usually dedicated to the theme of love and are probably inspired by the Italian poetic movement Dolce Stil Novo. The most notable work is Piruç myò doç inculurit (which means "My pear, all colored"); it was composed by an anonymous author from Cividale del Friuli, probably in 1380.

| Original text | Version in modern Friulian |

|---|---|

| Piruç myò doç inculurit

quant yò chi viot, dut stoi ardit |

Piruç gno dolç incolorît

cuant che jo ti viôt, dut o stoi ardît |

There are few differences in the first two rows, which demonstrates that there has not been a great evolution in the language except for several words which are no longer used (for example, dum(n) lo, a word which means "child"). A modern Friulian speaker can understand these texts with only little difficulty.

The second important period for Friulian literature is the 16th century. The main author of this period was Ermes di Colorêt, who composed over 200 poems.

| Notable poets and writers: | Years active: |

|---|---|

| Ermes di Colorêt | 1622–1692 |

| Pietro Zorutti | 1792–1867 |

| Caterina Percoto | 1812–1887 |

| Novella Cantarutti | 1920–2009 |

| Pier Paolo Pasolini | 1922–1975 |

| Rina Del Nin Cralli (Canada) | 1929–2021 |

| Carlo Sgorlon | 1930–2009 |

Phonology edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2012) |

Consonants edit

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | (ŋ) | |

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | c | k |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ | ɡ | |

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | ||

| voiced | dz | dʒ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | (ʃ) | |

| voiced | v | z | (ʒ) | ||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||

Notes:

- /m, p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental and /w/ is labiovelar.

- Note that, in the standard language, a phonemic distinction exists between true palatal stops [c ɟ] and palatoalveolar affricates [tʃ dʒ]. The former (written ⟨cj gj⟩) originate from Latin ⟨c g⟩ before ⟨a⟩, whereas the latter (written ⟨c/ç z⟩, where ⟨c⟩ is found before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, and ⟨ç⟩ is found elsewhere) originate primarily from Latin ⟨c g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩. The palatalization of Latin ⟨c⟩ and ⟨g⟩ before ⟨a⟩ is characteristic of the Rhaeto-Romance languages and is also found in French and some Occitan varieties. In some Friulian dialects (e.g. Western dialects), corresponding to Central [c ɟ tʃ dʒ] are found [tʃ dʒ s z]. Note in addition that, due to various sound changes, these sounds are all now phonemic; note, for example, the minimal pair cjoc "drunk" vs. çoc "log".

Vowels edit

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː | |

| Close mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a aː |

Orthography edit

Some notes on orthography (from the perspective of the standard, i.e. Central, dialect):[9]

- Long vowels are indicated with a circumflex: ⟨â ê î ô û⟩.

- ⟨e⟩ is used for both /ɛ/ (which only occurs in stressed syllables) and /e/; similarly, ⟨o⟩ is used for both /ɔ/ and /o/.

- /j/ is spelled ⟨j⟩ word-initially, and ⟨i⟩ elsewhere.

- /w/ occurs primarily in diphthongs, and is spelled ⟨u⟩.

- /s/ is normally spelled ⟨s⟩, but is spelled ⟨ss⟩ between vowels (in this context, a single ⟨s⟩ is pronounced /z/).

- /ɲ/ is spelled ⟨gn⟩, which can also occur word-finally.

- [ŋ] is an allophone of /n/, found word-finally, before word-final -s, and often in the prefix in-. Both sounds are spelled ⟨n⟩.

- /k/ is normally spelled ⟨c⟩, but ⟨ch⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, as in Italian.

- /ɡ/ is normally spelled ⟨g⟩, but ⟨gh⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, again as in Italian.

- The palatal stops /c ɟ/ are spelled ⟨cj gj⟩. Note that in some dialects, these sounds are pronounced [tʃ dʒ], as described above.

- /tʃ/ is spelled ⟨c⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩, ⟨ç⟩ elsewhere. Note that in some dialects, this sound is pronounced [s].

- /dʒ/ is spelled ⟨z⟩. Note that in some dialects, this sound is pronounced [z].

- ⟨z⟩ can also represent /ts/ or /dz/ in certain words (e.g. nazion "nation", lezion "lesson").

- ⟨h⟩ is silent.

- ⟨q⟩ is no longer used except in the traditional spelling of certain proper names; similarly for ⟨g⟩ before ⟨e⟩ and ⟨i⟩.

Long vowels and their origin edit

Long vowels are typical of the Friulian language and greatly influence the Friulian pronunciation of Italian.

Friulian distinguishes between short and long vowels: in the following minimal pairs (long vowels are marked in the official orthography with a circumflex accent):

- lat (milk)

- lât (gone)

- fis (fixed, dense)

- fîs (sons)

- lus (luxury)

- lûs (light n.)

Friulian dialects differ in their treatment of long vowels. In certain dialects, some of the long vowels are actually diphthongs. The following chart shows how six words (sêt thirst, pît foot, fîl "wire", pôc (a) little, fûc fire, mûr "wall") are pronounced in four dialects. Each dialect uses a unique pattern of diphthongs (yellow) and monophthongs (blue) for the long vowels:

| Latin origin | West | Codroipo | Carnia | Central | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sêt "thirst" | SITIM | [seit] | [seːt] | [seit] | [seːt] |

| pît "foot" | PEDEM | [peit] | [peit] | [piːt] | [piːt] |

| fîl "wire" | FĪLUM | [fiːl] | [fiːl] | [fiːl] | [fiːl] |

| pôc "a little" | PAUCUM | [pouk] | [poːk] | [pouk] | [poːk] |

| fûc "fire" | FOCUM | [fouk] | [fouk] | [fuːk] | [fuːk] |

| mûr "wall" | MŪRUM | [muːr] | [muːr] | [muːr] | [muːr] |

Note that the vowels î and û in the standard language (based on the Central dialects) correspond to two different sounds in the Western dialects (including Codroipo). These sounds are not distributed randomly but correspond to different origins: Latin short E in an open syllable produces Western [ei] but Central [iː], whereas Latin long Ī produces [iː] in both dialects. Similarly, Latin short O in an open syllable produces Western [ou] but Central [uː], whereas Latin long Ū produces [uː] in both dialects. The word mûr, for example, means both "wall" (Latin MŪRUM) and "(he, she, it) dies" (Vulgar Latin *MORIT from Latin MORITUR); both words are pronounced [muːr] in Central dialects, but respectively [muːr] and [mour] in Western dialects.

Long consonants (ll, rr, and so on), frequently used in Italian, are usually absent in Friulian.

Friulian long vowels originate primarily from vowel lengthening in stressed open syllables when the following vowel was lost.[8] Friulian vowel length has no relation to vowel length in Classical Latin. For example, Latin valet yields vâl "it is worth" with a long vowel, but Latin vallem yields val "valley" with a short vowel. Long vowels aren't found when the following vowel is preserved, e.g.:

- before final -e < Latin -a, cf. short nuve "new (fem. sg.)" < Latin nova vs. long nûf "new (masc. sg.)" < Latin novum;

- before a non-final preserved vowel, cf. tivit /ˈtivit/ "tepid, lukewarm" < Latin tepidum, zinar /ˈzinar/ "son-in-law" < Latin generum, ridi /ˈridi/ "to laugh" < Vulgar Latin *rīdere (Classical rīdēre).

It is quite possible that vowel lengthening occurred originally in all stressed open syllables, and was later lost in non-final syllables.[10] Evidence of this is found, for example, in the divergent outcome of Vulgar Latin */ɛ/, which becomes /jɛ/ in originally closed syllables but /i(ː)/ in Central Friulian in originally open syllables, including when non-finally. Examples: siet "seven" < Vulgar Latin */sɛtte/ < Latin SEPTEM, word-final pît "foot" < Vulgar Latin */pɛde/ < Latin PEDEM, non-word-final tivit /ˈtivit/ "tepid, lukewarm" < Vulgar Latin */tɛpedu/ < Latin TEPIDUM.

An additional source of vowel length is compensatory lengthening before lost consonants in certain circumstances, cf. pâri "father" < Latin patrem, vôli "eye" < Latin oc(u)lum, lîre "pound" < Latin libra. This produces long vowels in non-final syllables, and was apparently a separate, later development than the primary lengthening in open syllables. Note, for example, the development of Vulgar Latin */ɛ/ in this context: */ɛ/ > */jɛ/ > iê /jeː/, as in piêre "stone" < Latin PETRAM, differing from the outcome /i(ː)/ in originally open syllables (see above).

Additional complications:

- Central Friulian has lengthening before /r/ even in originally closed syllables, cf. cjâr /caːr/ "cart" < Latin carrum (homophonous with cjâr "dear [masc. sg.]" < Latin cārum). This represents a late, secondary development, and some conservative dialects have the expected length distinction here.

- Lengthening doesn't occur before nasal consonants even in originally open syllables, cf. pan /paŋ/ "bread" < Latin panem, prin /priŋ/ "first" < Latin prīmum.

- Special developments produced absolutely word-final long vowels and length distinctions, cf. fi "fig" < Latin FĪCUM vs. fî "son" < Latin FĪLIUM, no "no" < Latin NŌN vs. nô "we" < Latin NŌS.

Synchronic analyses of vowel length in Friulian often claim that it occurs predictably in final syllables before an underlying voiced obstruent, which is then devoiced.[11] Analyses of this sort have difficulty with long-vowel contrasts that occur non-finally (e.g. pâri "father" mentioned above) or not in front of obstruents (e.g. fi "fig" vs. fî "son", val "valley" vs. vâl "it is worth").

Morphology edit

Friulian is quite different from Italian in its morphology; it is, in many respects, closer to French.

Nouns edit

In Friulian as in other Romance languages, nouns are either masculine or feminine (for example, "il mûr" ("the wall", masculine), "la cjadree" ("the chair", feminine).

Feminine edit

Most feminine nouns end in -e, which is pronounced, unlike in Standard French:

- cjase = house (from Latin "casa, -ae" hut)

- lune = moon (from Latin "luna, -ae")

- scuele = school (from Latin "schola, -ae")

Some feminine nouns, however, end in a consonant, including those ending in -zion, which are from Latin.

- man = hand (from Latin "manŭs, -ūs" f)

- lezion = lesson (from Latin "lectio, -nis" f

Note that in some Friulian dialects the -e feminine ending is actually an -a or an -o, which characterize the dialect area of the language and are referred to as a/o-ending dialects (e.g. cjase is spelled as cjaso or cjasa - the latter being the oldest form of the feminine ending).

Masculine edit

Most masculine nouns end either in a consonant or in -i.

- cjan = dog

- gjat = cat

- fradi = brother

- libri = book

A few masculine nouns end in -e, including sisteme (system) and probleme (problem). They are usually words coming from Ancient Greek. However, because most masculine nouns end in a consonant, it is common to find the forms sistem and problem instead, more often in print than in speech.

There are also a number of masculine nouns borrowed intact from Italian, with a final -o, like treno (train). Many of the words have been fully absorbed into the language and even form their plurals with the regular Friulian -s rather than the Italian desinence changing. Still, there are some purists, including those influential in Friulian publishing, who frown on such words and insist that the "proper" Friulian terms should be without the final -o. Despite the fact that one almost always hears treno, it is almost always written tren.

Articles edit

The Friulian definite article (which corresponds to "the" in English) is derived from the Latin ille and takes the following forms:

| Number | Masculine | Feminine |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | il | la |

| Plural | i | lis |

Before a vowel, both il and la can be abbreviated to l' in the standard forms - for example il + arbul (the tree) becomes l'arbul. Yet, as far as the article la is concerned, modern grammar recommends that its non elided form should be preferred over the elided one: la acuile (the eagle) although in speech the two a sounds are pronounced as a single one. In the spoken language, various other articles are used.[12]

The indefinite article in Friulian (which corresponds to a and an in English) derives from the Latin unus and varies according to gender:

| Masculine | un |

|---|---|

| Feminine | une |

A partitive article also exists: des for feminine and dai for masculine: des vacjis – some cows and dai libris - some books

Adjectives edit

A Friulian adjective must agree in gender and number with the noun it qualifies. Most adjectives have four forms for singular (masculine and feminine) and plural (masculine and feminine):

| Number | Masculine | Feminine |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | brut | brute |

| Plural | bruts | brutis |

(Like for nouns, for a/o-ending dialects the plural is simply obtained by adding an s - e.g. brute corresponds to bruta/bruto and its plural form brutis is brutas/brutos).

The feminine is formed in several ways from the masculine:

- in most cases, all that is needed is -e (short: curt, curte)

- if the final letter is a -c, the feminine can end with -cje, -gje, -che, -ghe (little: pôc, pôcje)

- if the final letter is a -f, the feminine can end with -ve (new: gnûf, gnove)

- if the final letter is a -p, the feminine can end with -be (sour: garp, garbe)

- if the final letter is a -t, the feminine can end with -de (green: vert, verde)

Plurals edit

To form the plural of masculine and feminine nouns ending in -e, the -e is changed to -is (whilst a/o-ending dialects simply add an s)

- taule, taulis = table, tables

- cjase, cjasis = house, houses

- lune, lunis = moon, moons

- scuele, scuelis = school, schools

- sisteme, sistemis = system, systems

- manece, manecis = glove, gloves

- gnece, gnecis = niece, nieces

The plural of almost all other nouns is just -s. It is always pronounced as voiceless [s], as in English cats, never as voiced [z], as in dogs.

- man, mans = hand, hands

- lezion, lezions = lesson, lessons

- cjan, cjans = dog, dogs

- gjat, gjats = cat, cats

- fradi, fradis = brother, brothers

- libri, libris = book, books

- tren, trens = train, trains

- braç, braçs = arm, arms (from Latin "bracchium")

- guant, guants = glove, gloves (compare English "gauntlet")

In some Friulian dialects, there are many words whose final consonant becomes silent when the -s is added. The words include just about all those whose singular form ends in -t. The plural of gjat, for example, is written as gjats but is pronounced in much of Friuli as if it were gjas. The plural of plat 'dish', though written as plats, is often pronounced as plas. Other words in this category include clâf (key) and clap (stone), whose plural forms, clâfs and claps, are often pronounced with no f or p, respectively (clâs, clas) so the longer a in the former is all that distinguishes it from the latter. A final -ç, which is pronounced either as the English "-ch" (in central Friulian) or as "-s", is pluralized in writing as -çs, regardless of whether the pluralized pronunciation is "-s" or "-ts" (it varies according to dialect): messaç / messaçs (message).

Exceptions edit

Masculine nouns ending in -l or -li form their plurals by palatalising final -l or -li to -i.

- cjaval, cjavai = horse, horses (from Latin "caballus")

- fîl, fîi = string, strings (from Latin "filum")

- cjapiel, cjapiei = hat, hats

- cjaveli, cjavei = hair, hairs

- voli, voi = eye, eyes

- zenoli, zenoi = knee, knees (from Latin "genu")

Notice how these very often correspond to French nouns that form an irregular plural in -x: cheval-chevaux, chapeau-chapeaux, cheveu-cheveux, oeil-yeux, genou-genoux.

Feminine nouns ending in -l have regular plurals.

- piel, piels = skin, skins

- val, vals (in northern Friulian also "tal", "tals") = valley, valleys

Masculine nouns ending in -st form their plurals by palatalising the final -t to -cj

- cavalarist, cavalariscj = military horseman, military horsemen

- test, tescj = text, texts

Some masculine nouns ending in -t form their plurals by palatalising the final -t to -cj:

- dint, dincj = tooth, teeth (from Latin "dens, -tis")

- dut, ducj = all (of one thing), all (of several things) (from Latin "totus")

Nouns ending in "s" do not change spelling in the plural, but some speakers may pronounce the plural -s differently from the singular -s.

- vues = bone, bones

- pes = fish (singular or plural) (from Latin "piscis")

- mês = month, months (from Latin "mensis")

The plural of an (year) has several forms depending on dialect, including ain, ains, agn and agns. Regardless of pronunciation, the written form is agns.

The same happens for the adjective bon (good), as its plural is bogns.

Clitic subject pronouns edit

A feature of Friulian are the clitic subject pronouns. Known in Friulian as pleonastics, they are never stressed; they are used together with the verb to express the subject and can be found before the verb in declarative sentences or immediately after it in case of interrogative or vocative (optative) sentences.

| Declaration | Question | Invocation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | o | -(i)o | -(i)o |

| You (singular) | tu | -tu | -tu |

| He | al | -(i)al | -(i)al |

| She | e | -(i)e | -(i)e |

| We | o | -o | -o |

| You (plural) | o | -o | -o |

| They | -a | -o | -o |

An example: jo o lavori means "I work"; lavorio? means "Do I work?", while lavorassio means "I wish I worked".

Verbs edit

- Friulian verbal infinitives have one of four endings, -â, -ê, -i, -î; removing the ending gives the root, used to form the other forms (fevelâ, to speak; root fevel-), but in the case of irregular verbs, the root changes. They are common (jessi, to be; vê, to have; podê, to be able to). Verbs are frequently used in combination with adverbs to restrict the meaning.

| Person | fevelâ (to speak) | lâ (to go) | jessi (to be) | vê (to have) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jo o | feveli | voi | soi | ai |

| Tu tu | fevelis | vâs | sês | âs |

| Lui al | fevele | va | è | à |

| Jê e | fevele | va | je | à |

| Nô o | fevelìn | lin | sin | vin |

| Vô o | fevelais | lais, vais | sês | vês |

| Lôr a | fevelin | van | son | àn |

Adverbs edit

An adjective can be made into an adverb by adding -mentri to the ending of the feminine singular form of the adjective (lente becomes lentementri, slowly), but it can sometimes[13] lose the -e of the adjective (facile becomes facilmentri, easily). It is more common in the written language; in the spoken language people frequently use other forms or locutions (a planc for slowly).

Vocabulary edit

Most vocabulary is derived from Latin, with substantial phonological and morphological changes throughout its history. Therefore, many words are shared with the other Romance languages,[14] Here the composition:

- Celtic (9%) words are many, because the substrate of the Vulgar Latin spoken in Friuli, was the Karn-Celtic language. ("bâr", wood; "clap/crap", stone;"cjâr", plow)

- Modern German (10%) words were introduced in particular in the Middle Ages, during the Patrie dal Friûl, when the influence from this culture was quite strong (bearç, backyard; "crot", frog/toad).

- Slavic (3%) words were brought by Slavic (mostly Alpine Slavic) immigrants called several times to Friuli to repopulate lands devastated by Hungarian invasions in the 10th century (cjast, barn; zigâ, to shout). Furthermore, many Slavic words have entered Friulian through the centuries-long neighbouring between Friulians and Slovenes, especially in north-eastern Friuli (Slavia Friulana) and in the Gorizia and Gradisca area. Words such as colaç (cake), cudiç (devil) and cos (basket) are all of Slovene origin. There are also many toponyms with Slavic roots.

- There are many words that have Germanic (8%, probably Lombardic origins) and Celtic roots (what still remained of the languages spoken before the Romans came). Examples of the first category are sbregâ, to tear; sedon, spoon; taponâ, to cover. For the latter category, troi, path; bragons, trousers.

- Latin and derived languages (68%):

- Venetian language influenced Friulian vocabulary: canucje, straw.

- Some French words entered the Friulian vocabulary: pardabon, really and gustâ, to have lunch.

- Italian itself has a growing influence on Friulian vocabulary, especially as far as neologisms are concerned (tren meaning train). Such neologisms are currently used even if they're not accepted in the official dictionary (for example the verb "to iron" is sopressâ but the verb stirâ taken from Italian is used more and more instead).

- Scientific terms are often of Greek origin, and there are also some Arabic terms in Friulian (<1%, lambic, still).

- Many English words (such as computer, monitor, mouse and so on) have entered the Friulian vocabulary through Italian. (more than 1%).

Present condition edit

Nowadays, Friulian is officially recognized in Italy, supported by law 482/1999, which protects linguistic minorities. Therefore, optional teaching of Friulian has been introduced in many primary schools. An online newspaper is active, and there are also a number of musical groups singing in Friulian and some theatrical companies. Recently, two movies have been made in Friulian (Tierç lion, Lidrîs cuadrade di trê), with positive reviews in Italian newspapers. In about 40% of the communities in the Province of Udine, road signs are in both Friulian and Italian. There is also an official translation of the Bible. In 2005, a notable brand of beer used Friulian for one of its commercials.

The main association to foster the use and development of Friulian is the Societât filologjiche furlane, founded in Gorizia in 1919.

Toponyms edit

Every city and village in Friuli has two names, one in Italian and one in Friulian. Only the Italian is official and used in administration, but it is widely expected[citation needed] that the Friulian ones will receive partial acknowledgement in the near future. For example, the city of Udine is called Udin in Friulian, the town of Tolmezzo Tumieç and the town of Aviano is called both Davian and Pleif.

Standardisation edit

A challenge that Friulian shares with other minorities is to create a standard language and a unique writing system. The regional law 15/1996 approved a standard orthography, which represents the basis of a common variant and should be used in toponyms, official acts, written documents. The standard is based on Central Friulian, which was traditionally the language used in literature already in 1700 and afterwards (the biggest examples are probably Pieri Çorut's works) but with some changes:

- the diphthong ie replaces ia: fier (iron) instead of fiar, tiere (soil, earth) instead of tiare.

- the use of vu instead of u at the beginning of word: vueli (oil) instead of ueli , vueit (empty) instead of ueit.

- the use of i between vocals: ploie (rain) instead of ploe.

Standard Friulian is called in Friulian furlan standard, furlan normalizât or from Greek, coinè.

Criticism edit

There have been several critics of the standardisation of Friulian, mainly from speakers of local variants that differ substantially from the proposed standard; they also argue that the standard could eventually kill local variants. The supporters of standardisation refer to the various advantages that a unique form can bring to the language. Above all, it can help to stop the influence of Italian language in the neologisms, which pose a serious threat to Friulian's future development. They also point out that it is a written standard without affecting pronunciation, which can follow local variants.

Opponents of the standardisation, on the other hand, insist that the standard language, being artificially created, is totally inadequate to represent the local variations, particularly from differences in the phonetic pronunciation of the words in each variant that may, in some cases, even require special and different diacritics for writing a single variant.

Variants of Friulian edit

Four dialects of Friulian can be at least distinguished, all mutually intelligible. They are usually distinguished by the last vowel of many parts of speech (including nouns, adjectives, adverbs), following this scheme:

- Central Friulian, spoken around Udine has words ending with -e. It is used in official documents and generally considered standard. Some people see it as the least original but one of the most recent variants since it does not show interesting features found in other variants, as it has Venetian influence.

- Northern Friulian, spoken in Carnia, has several variants. The language can vary with the valleys and words can end in -o, -e or -a. It is the most archaic variant.

- Southeastern Friulian, spoken in Bassa Friulana and Eastern Friuli, in the area along the Isonzo River (the area of the old Contea di Gorizia e Gradisca), has words that end with -a. This variant has been known since the origins of the language and was used as official literary language by the Friulians of the Austrian Empire. It was influenced by German and Slavic.

- Western Friulian, including Pordenonese, is spoken in the Province of Pordenone and is also called concordiese, from Concordia Sagittaria. Words end with -a or -e, but the strong Venetian influence, makes it be considered one of the most corrupted variants.

The word for home is cjase in Central Friulian and cjasa or cjaso in other areas. Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote his works in Western Friulian since he learned the language from his mother who was from Casarsa/Cjasarsa,[15] near Pordenone.

In the 13th century, early literary works in Friulian were based on the language spoken in Cividale del Friuli, which was the most important town in Friuli. The endings in -o, which now is restricted to some villages in Carnia. Later, the main city of Friuli became Udine and the most common ending was -a; only from the 16th century on, -e endings were used in standard Friulian.

Writing systems edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2012) |

In the official writing system, approved by the (former, abolished in 2017) Province of Udine and used in official documents, Friulian is written using the Latin script with the c-cedilla (ç). The letter q is used only for personal names and historical toponyms, and in every other case, it is replaced by c. Besides that, k, x, w, and y appear only in loan words so they are not considered part of the alphabet.

- Aa Bb Cc Çç Dd Ee Ff Gg Hh Ii Jj Ll Mm Nn Oo Pp Qq Rr Ss Tt Uu Vv Zz

There are also grave accents (à, è, ì, ò and ù) and circumflex accents (â, ê, î, ô, and û), which are put above the vowels to distinguish between homophonic words or to show stress (the former) and show long vowels (the latter).

Other systems edit

An alternative system is called Faggin-Nazzi from the names of the scholars who proposed it. It is less common, probably also because it is more difficult for a beginner for its use of letters, such as č, that are typical of Slavic languages but seem foreign to native Italian speakers.

Examples edit

| English | Friulian |

|---|---|

| Hello; my name is Jack! | Mandi, o mi clami Jacum (Jack)! |

| The weather is really hot today! | Vuê al è propit cjalt! |

| I really have to go now; see you. | O scugni propit lâ cumò, ariviodisi. |

| I can't go out with you tonight; I have to study. | No pues vignî fûr cun te usgnot, o ai di studiâ. |

The Fox and the Crow translation in Central Friulian edit

La bolp e jere di gnûf famade. In chel e a viodût un corvat poiât suntun pin, ch'al tigneve un toc di formadi tal bec. "Chel si che mi plasarès!" e a pensât le bolp, e e disè al corvát: "Ce biel che tu sês! Se il to cjant al é biel come il to aspiet, di sigûr tu sês il plui biel di ducj i ucei!

References edit

- Paola Benincà & Laura Vanelli. Linguistica friulana. Padova: Unipress, 2005.

- Paola Benincà & Laura Vanelli. "Friulian", in The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages, eds. Adam Ledgeway & Martin Maiden. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, pp. 139–53.

- Franc Fari, ed. Manuâl di lenghistiche furlane. Udine: Forum, 2005.

- Giuseppe Francescato. Dialettologia friulana. Udine: Società Filologica Friulana, 1966.

- Giovanni Frau. I dialetti del Friuli. Udine: Società Filologica Friulana, 1984.

- Sabine Heinemann. Studi di linguistica friulana. Udine: Società Filologica Friulana, 2007.

- Carla Marcato. Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Rome–Bari: Laterza, 2001.

- Nazzi, Gianni & Deborah Saidero, eds. Friulan Dictionary: English-Friulan / Friulan-English. Udine: Ent. Friul tal Mond, 2000.

- Piera Rizzolati. Elementi di linguistica friulana. Udine: Società Filologica Friulana, 1981.

- Paolo Roseano. La pronuncia del friulano standard: proposte, problemi, prospettive, Ce Fastu? LXXXVI, vol. 1 (2010), p. 7–34.

- Paolo Roseano. Suddivisione dialettale del friulano, in Manuale di linguistica friulana, eds. S. Heinemann & L. Melchior. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2015, pp. 155–186.

- Federico Vicario, ed. Lezioni di lingua e cultura friulana. Udine: Società Filologica Friulana, 2005.

- Federico Vicario. Lezioni di linguistica friulana. Udine: Forum, 2005.

- "Sociolinguistic Condition". Regional Agency for Friulian Language. Archived from the original on 2019-02-22.

Notations edit

The grammar section is based on An introduction to Friulan by R. Pontisso. Some parts are also based loosely on Gramatiche furlane by Fausto Zof, Edizioni Leonardo, Udine 2002.

Footnotes edit

- ^ a b Friulian at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (2022-05-24). "Friulian". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 2022-07-09. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Aquileia Cristiana". www.regionefvg.com. Archived from the original on 2003-04-05.

- ^ Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (2016). The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780199677108.

- ^ Fucilla, Joseph Guerin (1949). Our Italian Surnames. Genealogical Publishing Com. p. 31. ISBN 9780806311876.

- ^ Pavel Iosad, Final devoicing and vowel lengthening in the north of Italy: A representational approach, Slides, Going Romance 24, December 10th 2010, Universiteit Leiden, Academia Lugduno Batava [1]

- ^ Miotti, Renzo (2002). "Friulian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 32 (2): 242. doi:10.1017/S0025100302001056.

- ^ a b Prieto, Pilar (1992), "Compensatory Lengthening by Vowel and Consonant Loss in Early Friulian", Catalan Working Papers in Linguistics: 205–244

- ^ "The Furlan / Friulian Alphabet". www.geocities.ws. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Loporcaro, Michele (2005), "(Too much) synchrony within diachrony? Vowel length in Milanese.", GLOW Phonology Workshop (PDF)

- ^ Torres-Tamarit, Francesc (2015), "Length and voicing in Friulian and Milanese" (PDF), Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 33 (4): 1351–1386, doi:10.1007/s11049-014-9271-7, S2CID 170893106

- ^ In Northern Friuli, el is used instead of il. In Southern and Western Friuli, al is used instead of il. In Northern Friuli, li or las is used instead of lis and le instead of la.

- ^ Such is the case of FriulIan adjectives deriving from Latin adjectives of the second class.

- ^ "Language similarity table". slu.edu. Archived from the original on 1 May 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ "casarsa_casa Pasolini (Colussi) a Casarsa". pasolini.net. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

External links edit

- Short video showing bilingual Italian/Friulian road signs

- Radio Onde Furlane. Radio in Friulian language.

- Grafie uficiâl de lenghe furlane — Agjenzie regjonal pe lenghe furlane (different other language resources) Archived 2011-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Dante in furlan: [3]

- Provincie di Udin-Provincia di Udine: La lingua friulana Archived 2011-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- La Patrie dal Friûl; Magazine and News in Friulian language since 1946

- Lenghe.net – Online bilingual magazine in Friulian language (2004–2010)

- Online magazine and resources

- The juridical defence of Friulian (in English)

- Course of Friulian

- Friulian Journal of Science – an association to foster the use of Friulian in the scientific world

- Fogolâr furlan of Toronto

- Fogolâr Furlan of Windsor

- Societat Filologjiche Furlane

- Centri interdipartimentâl pe ricercje su la culture e la lenghe dal Friûl "Josef Marchet"

- Friulian version of Firefox browser

- Centri Friûl Lenghe 2000, Online bilingual dictionary (Italian/Friulian) with online tools

- Furlan English Dictionary from Webster's Online Dictionary – The Rosetta Edition

- C-evo Furlan – a computer game in Friulian

- Italian-Friulian Dictionary

- Friulian-Italian-Slovenian-German-English-Spanish-French Multilingual Dictionary

- Friulian basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Friulian-English English-Friulian dictionary – uses the Faggin-Nazzi alphabet