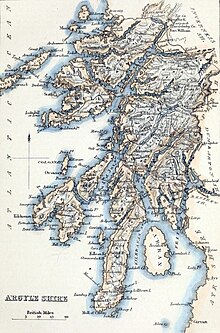

Argyll (/ɑːrˈɡaɪl/; archaically Argyle; Scottish Gaelic: Earra-Ghàidheal, pronounced [ˈaːrˠəɣɛːəl̪ˠ]), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland. The county ceased to be used for local government purposes in 1975 and most of the area now forms part of the larger Argyll and Bute council area.

| Argyll Earra-Ghàidheal (Scottish Gaelic) | |

|---|---|

| Historic county | |

| |

| Area | |

| • Coordinates | 56°15′N 5°15′W / 56.250°N 5.250°W |

| History | |

| • Preceded by | Dál Riata; Lordship of the Isles |

| • Abolished | 1975 |

| • Succeeded by | Strathclyde (Region, 1975-1996); Argyll and Bute (District, 1975–1996, Council area 1996–) |

| Chapman code | ARL |

Argyll is of ancient origin, and broadly corresponds to the ancient kingdom of Dál Riata less the parts which were in Ireland. Argyll was also a medieval bishopric with its cathedral at Lismore. In medieval times the area was divided into a number of provincial lordships. One of these, covering only the central part of the later county, was called Argyll. It was initially an earldom, elevated to become a dukedom in 1701 with the creation of the Duke of Argyll. Other lordships in the area included Cowal, Kintyre, Knapdale, and Lorn. From at least the 14th century there was a Sheriff of Argyll, whose jurisdiction was gradually extended; from 1633 the shire covered all these five provinces. Shires gradually eclipsed the old provinces in administrative importance, and also became known as counties. Between 1890 and 1975, Argyll had a county council. The county town was historically Inveraray, but from its creation in 1890 the county council was based at Lochgilphead.

The county is sparsely populated, with many islands and sea lochs along its coast, and the inland parts are mountainous. Six towns in the county held burgh status: Campbeltown, Dunoon, Inveraray, Lochgilphead, Oban, and Tobermory. Argyll borders Inverness-shire to the north, Perthshire and Dunbartonshire to the east, and (separated by the Firth of Clyde) neighbours Renfrewshire and Ayrshire to the south-east, and the County of Bute to the south.

Argyll ceased to be used for local government purposes in 1975. Most of the pre-1975 county was then included in the Argyll and Bute district of the Strathclyde region. The district created in 1975 excluded the Morvern and Ardnamurchan areas from the pre-1975 county, which were transferred to the Highland region, but included the Isle of Bute, which had not been in Argyll. Further reforms in 1996 abolished the Strathclyde region and made Argyll and Bute a single-tier council area instead. As part of those reforms, Argyll and Bute also gained an area around Helensburgh which had historically been in Dunbartonshire.

Name

editThe name is generally said to derive from Old Irish airer Goídel, meaning "border region of the Gaels". The early 13th-century author of De Situ Albanie wrote that "the name Arregathel means the margin (i.e., border region) of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called Gattheli (i.e. Gaels), from their ancient warleader known as Gaithelglas." The word airer also means "coast" when applied to maritime regions, so the name can also be translated as "coast of the Gaels".[1]

An alternative theory has more recently been advanced that the name may actually come from the early Irish kingdom of Airgíalla.[2]

The legal name of the county was Argyll,[3] which was also used by the Royal Mail as the name of the postal county for the mainland (the islands formed their own postal counties).[4] The Ordnance Survey adopted the alternative form 'Argyllshire' for the county on its maps.[5]

History

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 81,277 | — |

| 1811 | 86,541 | +6.5% |

| 1821 | 97,316 | +12.5% |

| 1831 | 100,973 | +3.8% |

| 1841 | 97,371 | −3.6% |

| 1851 | 89,298 | −8.3% |

| 1901 | 73,642 | −17.5% |

| 1911 | 70,902 | −3.7% |

| 1921 | 76,862 | +8.4% |

| 1931 | 63,050 | −18.0% |

| 1951 | 63,361 | +0.5% |

| Source: [6] | ||

The Kilmartin Glen has standing stones and other monuments dating back to around 3000 BC, and is one of the most significant areas for Neolithic and Bronze Age remains in mainland Scotland. In 563 AD Iona Abbey was founded, becoming one of the most important early Christian sites in Scotland.[7]

The Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata existed between the 5th and 9th centuries. Its territory covered north-eastern parts of Ireland in what later became County Antrim, part of the mainland of Great Britain in what is now western Scotland, and numerous islands in the Inner Hebrides. A fortress at Dunadd in the Kilmartin Glen, 4 miles (6.4 km) north-west of the modern town of Lochgilphead, served as the main seat of the kingdom.[8] Dál Riata fragmented in the 9th century during the Viking Age; the part in Ireland was absorbed into the kingdom of Ulaid, the islands came under the control of the Kingdom of the Isles, and the part on mainland Britain was united in 843 AD with the Pictish kingdom to its east under Kenneth MacAlpin to become the Kingdom of Alba.[9]

The name Argyll (Airer Goídel), meaning 'coast or borderland of the Gaels', came to be used for the part of the former Dál Riata territory on mainland Britain. The name distinguished the area from the Innse Gall, meaning 'islands of the foreigners' which was used for the Kingdom of the Isles, ruled by Old Norse-speaking Norse–Gaels.[1]

Argyll was divided into several lordships or provinces, including Kintyre, Knapdale, Lorn, Cowal, and a smaller Argyll province which covered the area around Inveraray between Loch Fyne and Loch Awe (the latter sometimes described by later writers as "Argyll proper" or "Mid-Argyll" to distinguish it from the wider area).[10] The term "North Argyll" was also used to refer to the area later called Wester Ross. It was called North Argyll as it was settled by missionaries and refugees from Dál Riata, based at the abbey of Applecross. The position of abbot was hereditary, and when Ferchar mac in tSagairt, son of the abbot, became the Earl of Ross in the 13th century, the region of North Argyll gradually became known as Wester Ross instead.

Alba evolved into the kingdom of Scotland, but lost control of Kintyre, Knapdale and Lorn to Norwegian rule, as was acknowledged in a treaty of 1098 between Edgar, King of Scotland and Magnus Barefoot, King of Norway.[11] In 1266, the Treaty of Perth re-established the Scottish crown's authority over the parts of Argyll which had been under Norwegian rule, along with the former Kingdom of the Isles, which together became the semi-independent Lordship of the Isles.[9][12]

By this time, the rest of the area under Scottish rule was divided into shires, administered by sheriffs. The shires covered different territories to the provinces, and it was the shires which subsequently evolved into Scotland's counties rather than the older provinces. Following the Treaty of Perth, the Argyll provinces were initially placed in the shire of Perth. In 1293, two new shires were created within Argyll; the Sheriff of Kintyre, covering just that province, and the Sheriff of Lorn, covering Lorn, Knapdale, and Mid-Argyll (which probably included Cowal at that time).[13]

The earliest reference to a Sheriff of Argyll was in 1326.[14] The position appears to have been a re-establishment or renaming of the position of the Sheriff of Lorn. The post subsequently became a hereditary position held by members of Clan Campbell.[15]

Despite the creation of the shires, much of the area remained under the practical control of the Lord of the Isles until 1476, when John MacDonald, last Lord of the Isles, quitclaimed Kintyre, Knapdale, and Mid-Argyll to full Scottish control. In 1481, Knapdale was added to the shire of Kintyre which then became known as Tarbertshire, being initially administered from Tarbert.[16]

The Scottish Reformation coincidentally followed the fall of the Lordship of the Isles. The MacDonalds (the clan of the former Lords of the Isles) were strong supporters of the former religious regime. The Campbells, by contrast, were strong supporters of the reforms. At the start of the 17th century, under instruction from James VI, the Campbells were sent to the MacDonald territory at Islay and Jura, which they subdued and added to the shire of Argyll. Campbell pressure at this time also led to the sheriff court for Tarbertshire being moved to Inverary, where the Campbells held the court for the sheriff of Argyll. Tarbertshire was subsequently abolished by an act of parliament in 1633, being absorbed into the shire of Argyll. The act also confirmed the town of Inveraray's position as "head burgh" of the enlarged shire.[17]

In 1667, Commissioners of Supply were established for each shire, which would serve as the main administrative body for the area until the creation of county councils in 1890.[18]

David II had restored MacDougall authority over Lorn in 1357, but John MacDougall (head of the MacDougalls) had already renounced claims to Mull (in 1354) in favour of the MacDonalds, to avoid potential conflict. The MacLeans were an ancient family based in Lorn (including Mull), and following the quitclaim, they no longer had a Laird in Mull, so themselves became Mull's Lairds. Unlike the MacDonalds, they were fervent supporters of the Reformation, even supporting acts of civil disobedience against king Charles II's repudiation of the Solemn League and Covenant. Archibald Campbell (Earl of Argyll) was instructed by the privy council to seize Mull, and suppress the non-conformist behaviour; by 1680 he gained possession of the island, and transferred shrieval authority to the sheriff of Argyll.

In 1746, following Jacobite insurrections, the Heritable Jurisdictions Act abolished regality, and forbade the position of sheriff from being inherited. Local governance was brought into line with that of the rest of the recently unified Great Britain, and the English term "county" came to be used interchangeably with the term "shire". In 1890, elected county councils were created under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889.

The 1889 Act also led to parish and county boundaries being adjusted to eliminate cases where parishes straddled county boundaries. The parish of Small Isles straddled Argyll and Inverness-shire, with the islands of Muck, Rùm, Canna, and Sanday being in Argyll but Eigg in Inverness-shire. The whole parish was placed in Inverness-shire in 1891. The parishes of Ardnamurchan and Kilmallie both also straddled Argyll and Inverness-shire; the county boundary through Kilmallie was adjusted to follow Loch Eil in 1891.[19] In 1895 these two parishes were both split along the county boundary; the part of Ardnamurchan in Inverness-shire became a new parish of Arisaig and Moidart, leaving the reduced Ardnamurchan parish wholly in Argyll, whilst the part of Kilmallie in Argyll became a new parish of Ardgour.[20][21]

Argyll was abolished as a county for local government purposes in 1975, with its area being split between Highland and Strathclyde Regions. A local government district called Argyll and Bute was formed in the Strathclyde region, including most of Argyll and the adjacent Isle of Bute (the former County of Bute was more extensive). The Ardnamurchan, Ardgour, Ballachulish, Duror, Glencoe, Kinlochleven, and Morvern areas of Argyll were detached to become parts of Lochaber District, in Highland. They remained in Highland following the 1996 revision.

In 1996, a new unitary council area of Argyll and Bute was created, with a change in boundaries to include part of the former Strathclyde district of Dumbarton. The historic county boundaries of Argyll are still used for some limited official purposes connected with land registration, being a registration county.[22]

County council

editArgyll County Council held its first meeting at the courthouse in Inveraray on 22 May 1890, when over three hours were spent debating where the council should meet thereafter, with proposals put forward in favour of meeting in Lochgilphead, Inveraray, Oban, Dunoon, or even Glasgow (despite the latter being outside the county). It was decided to meet at Dunoon between May and September and at Oban for the rest of the year.[23] The council did subsequently hold meetings in more places than just those two towns, meeting occasionally at all the towns which had been suggested at that first meeting.[24]

The council also appointed a clerk who was based in Lochgilphead at its first meeting, beginning the practice of having the council's main offices in that town.[23][25] The clerk's offices were initially at the County Offices which formed part of Lochgilphead's courthouse and police station on Lochnell Street, which had been built in 1849.[26][27][28] In 1925 the council bought the former Argyll Hotel at 5 Lochnell Street for £2,700, converting it to become their offices.[a] The hotel had been built in 1887, and was renamed County Offices.[30][31] The Lochgilphead building was not large enough to house all the council's staff, and some departments remained in other towns throughout the county council's existence, with the county treasurer being based in Campbeltown, the health department in Oban, and the education offices in Dunoon.[24][32]

After the county council's abolition in 1975, the building at 5 Lochnell Street became the sub-regional office of Strathclyde Regional Council, being renamed "Dalriada House", whilst the new Argyll and Bute District Council established its headquarters at nearby Kilmory Castle.[33][34]

Geography

editArgyll is split into two non-contiguous mainland sections divided by Loch Linnhe, plus a large number of islands that fall within the Inner Hebrides. Mainland Argyll is characterised by mountainous Highland scenery interspersed with hundreds of lochs, with a heavily indented coastline containing numerous small offshore islands. The islands present a contrasting range of scenery – from the relatively flat islands of Coll and Tiree to the mountainous terrain of Jura and Mull. For ease of reference the following is split into three sections: Mainland (north), Mainland (south) and the Inner Hebrides.

Mainland (north)

editThe northern mainland section consists of two large peninsulas – Ardnamurchan and Morvern – divided by Loch Sunart, with a large inland section – known traditionally as Ardgour – bounded on the east by Loch Linnhe. This loch gradually narrows, before turning sharply west in the vicinity of Fort William (where it is known as Loch Eil), almost cutting the northern mainland section of Argyll in two. This area, in the vicinity of Fort William and along the railway line, contains the largest towns of northern mainland Argyll.

Ardnamurchan is a remote, mountainous region with only one access road; it terminates in Ardnamurchan Point and Corrachadh Mòr, the westernmost points of the British mainland. In the north-east of the peninsula two unnamed sub-peninsulas almost encircle Kentra Bay, and are bound by the South Channel of Loch Moidart to the north; to the east of this lies the River Shiel and then Loch Shiel, a long loch which forms most of this section of the border with Inverness-shire. Morvern is a large peninsula and like its northern neighbour is remote, mountainous and sparsely populated. In its north-west Loch Teacuis cuts deeply into the peninsula, as does Loch Aline in the south. At the estuary of Loch Teacuis lie the large islands of Oronsay, Risga and Càrna. There are numerous lochs in northern Argyll, the largest being Loch Doilet, Loch Arienas, Loch Teàrnait, Loch Doire nam Mart and Loch Mudle.

List of islands

edit- Am Brican

- Ardtoe Island

- Big Stirk

- Càrna

- Dearg Sgeir

- Dubh Sgeir

- Eilean a' Chuilinn

- Eilean a' Mhuirich

- Eilean an Fhèidh

- Eilean an t-Sionnaich

- Eilean Ghleann Fhionainn

- Eilean Mhic Dhomhnuill Dhuibh

- Eilean mo Shlinneag

- Eilean Mòr, Loch Sunart

- Eilean Mòr, Loch Sunart (inner)

- Eilean na h-Acarseid

- Eilean na Beitheiche

- Eilean nam Gillean

- Eilean nan Eildean

- Eilean nan Gabhar

- Eilean nan Gall

- Eilean Rubha an Ridire

- Eilean Uillne

- Eileanan Glasa

- Eileanan Loisgte

- Eileanan nan Gad

- Garbh Eilean

- Glas Eilean (inner Loch Sunart)

- Glas Eilean (outer Loch Sunart)

- Glas Eileanan

- Little Stirk

- Oronsay

- Red Rocks

- Risga

- Seilag

- Sgeir an Eididh

- Sgeir an t-Seangain

- Sgeir Buidhe

- Sgeir Charrach

- Sgeir Ghobhlach

- Sgeir Horsgeat

- Sgeir Mhali

- Sgeir Mhòr

- Sgeir nan Gillean

- Sgeirean nan Torran

- Sgeirean Shallachain

- Sligneach Bag

- Sligneach Mòr

-

Corrachadh Mòr as seen from the Ardnamurchan Point lighthouse

-

Loch Sunart

-

Creach Bheinn on the Morvern peninsula

-

The isle of Risga

-

Kentra Moss flatlands

Mainland (south)

editThe southern mainland section is much larger than the northern, and is dominated by the long Kintyre peninsula, the terminus of which lies only 13 miles (21 kilometres) from Northern Ireland on the other side of the North Channel. The coast is complex, with the west coast in particular being heavily indented and containing numerous sea inlets, peninsulas and sub-peninsulas; of the latter, the major ones (north to south) are Appin, Ardchattan, Craignish, Tayvallich, Taynish, Knapdale and Kintyre, and the major loch inlets (north to south) are Loch Leven, Loch Creran, Loch Etive, Loch Feochan, Loch Melfort, Loch Craignish, Loch Crinan, Loch Sween, Loch Caolisport and West Loch Tarbert, the latter dividing Kintyre from Knapdale. To the east Loch Fyne separates Kintyre from the Cowal peninsula, which is itself split into three sub-peninsulas by Lochs Striven and Riddon and split on its east coast by Holy Loch and Loch Goil; south across the Kyles of Bute lies the island of Bute, which is part of Buteshire, and to east across Loch Long lies the Rosneath peninsula in Dunbartonshire. The topography of south Argyll is in general heavily mountainous and sparsely populated, with numerous lochs; Kintyre is slightly flatter though still hilly. Near Glen Coe can be found Bidean nam Bian, the tallest peak in the county at 1,150 m (3,770 ft). Of the lochs and bodies of water the largest are (roughly north to south) the Blackwater Reservoir, Loch Achtriochtan, Loch Laidon, Loch Bà, loch Buidhe, Lochan na Stainge, Loch Dochard, Loch Tulla, Loch Shira, the Cruachan Reservoir, Loch Restil, Loch Awe, Loch Avich, Blackmill Loch, Loch Nant, Loch Nell, Loch Scammadale, Loch Glashan, Loch Loskin, Loch Eck, Asgog Loch, Loch Tarsan, Càm Loch, Loch nan Torran, Loch Ciàran, Loch Garasdale, Lussa Loch and Tangy Loch.

List of islands

editNote that islands lying off the west coast are generally considered to be part of the Inner Hebrides (see below)

- Abbot's Isle

- An Oitir

- Barmore Island

- Black Islands

- Burnt Islands (comprising Eilean Mòr, Eilean Fraoich and Eilean Buidhe)

- Island Davaar

- Duncuan Island

- Eilean a' Chòmhraidh

- Eilean an t-Sagairt

- Eilean Aoghainn

- Eilean Beith

- Eilean Buidhe

- Eilean Dubh

- Eilean Grianain

- Eilean Math-ghamhna

- Eilean Mòr

- Eilean Munde

- Eilean nam Meann

- Glas Eilean

- Gluniform Island

- Henrietta Reef

- Inis Chonain

- Inishail

- Innis Errich

- Island Ross

- Liath Eilean

- Oitir Mòr

- Sanda Island

- Scart Rocks

- Sgat Beag

- Sgat Mòr

- Sgeir Bhuide

- Sgeir Caillich

- Sgeir Lag Choan

- Sgeir Leathann

- Sgeir Mhaola Cin

- Sgeir na Dubhaidh

- Sgeir Port a' Ghuail

- Sheep Island

- Thorn Isle

-

Knapdale scenery

-

Mull of Kintyre lighthouse

-

Loch Riddon

-

Loch Etive looking NE from Sron nam Feannag

-

Glen Coe, with the Three Sisters of Bidean nam Bian

-

Loch Restil

-

Davaar island

Inner Hebrides

editArgyll contains the majority of the Inner Hebrides group, with the notable exceptions of Skye and Eigg (both in Inverness-shire). The islands are too geographically diverse to be summarised here; further details can be found on the individual pages below.

List of islands

edit- Am Fraoch Eilean

- An Dubh Sgeir

- An Stèidh

- Bach Island

- Balach Rocks

- Belnahua

- Bernera Island

- Brosdale Island

- Calve Island

- Canna

- Cara Island

- Carraig an Daimh

- Carsaig Island

- Coiresa

- Coll

- Colonsay

- Craro Island

- Island of Danna

- Dubh Artach

- Dubh Sgeir

- Eagamol

- Eag na Maoile

- Easdale

- Eilean a' Chalmain

- Eilean a' Chùirn

- Eilean a' Mhadaidh

- Eilean Àird nan Uan

- Eilean an Aodaich

- Eilean an Fhuarain

- Eileach an Naoimh

- Eilean Annraidh

- Eilean an Righ

- Eilean Arsa

- Eilean Ascaoineach

- Eilean Balnagowan

- Eilean Bàn

- Eilean Bhrìde

- Eilean Coltair

- Eilean Craobhach

- Eilean dà Ghallagain

- Eilean dà Mhèinn

- Eilean Dioghlum

- Eilean Dùin

- Eilean Fraoich

- Eilean Gainimh

- Eilean Garbh

- Eilean Ghòmain

- Eilean Ghreasamuill

- Eilean Imersay

- Eilean Inshaig

- Eilean Loain

- Eilean Loch Oscair

- Eilean Mhartan

- Eilean Mhic Chrion

- Eilean Mhic Coinnich

- Eilean Mòr

- Eilean Musdile

- Eilean na Cloiche

- Eilean na Cille

- Eilean na Creiche

- Eilean na h-Eairne

- Eilean na h-Uamha

- Eilean na Seamair

- Eilean nam Ban

- Eilean nam Muc

- Eilean nan Caorach

- Eilean nan Coinean

- Eilean nan Each

- Eilean nan Gamhna

- Eilean Odhar

- Eilean Ona

- Eilean Ornsay

- Eilean Ramsay

- Eilean Reilean

- Eilean Righ

- Eilean Tràighe

- Eileanan Glasa

- Eileanan na h-Aoran

- Eorsa

- Erisgeir

- Eriska

- Erraid

- Fladda

- Frenchman's Rocks

- Gamhna Gigha

- Gamhnach Mhòr

- Garbh Rèisa

- Garbh Sgeir

- Garvellachs

- Gigalum Island

- Gigha

- Gòdag

- Gometra

- Guirasdeal

- Hàslam

- Humla

- Inch Kenneth

- Inn Island

- Insh Island

- Iona

- Island Macaskin

- Islay

- Hough Skerries

- Hyskeir (in Gaelic, Oigh-Sgeir)

- Jura

- Kerrera

- Lady's Rock

- Liath Sgeir

- Lismore

- Little Colonsay

- Luing

- Lunga

- MacCormaig Isles

- Maisgeir

- Muck

- Na Sgeiran Mòra

- Nave Island

- Ormsa

- Oronsay

- Orsay

- Rèidh Eilean

- Rèisa an t-Struith

- Rèisa Mhic Phaidean

- Ruadh Sgeir

- Rùm

- Samalan Island

- Sanday

- Scarba

- Scoul Eilean

- Seil

- Sgeir a' Mhàim-àrd

- Sgeir a' Phuirt

- Sgeir an Ròin

- Sgeiran Mòra

- Sgeir Mhòr

- Sgeir na Caillich

- Sgeir nan Gobhar

- Sgeir nan Sgarbh

- Sgeir Shealg

- Sgeir Tràighe

- Shian Island

- Shuna, Slate Islands

- Shuna Island, Loch Linnhe

- Skerryvore

- Small Isles

- Soa, near Coll

- Soa, Tiree

- Soa, near Mull

- Staffa

- Taynish Island

- Sùil Ghorm

- Texa

- Tiree

- Torran Rocks

- Torsa

- Treshnish Isles

- Ulva

-

Calve Island

-

Cliffs at Iorcail on Canna

-

Cara

-

Eorsa from Mull

-

Iona Abbey

-

Dun Nosebridge on Islay

-

Gylen Castle on Kerrera

-

Ponies on Rum

-

Coastal waterfall on Rum

-

Basalt columns on Staffa

-

Bluebell field on Ulva

Constituency

editStarting in 1590, as one of the measures that followed the Scottish reformation, each sheriffdom elected commissioners to the Parliament of Scotland. As well as the commissioner representing Argyll, at least one was sent to represent Tarbertshire, Sir Lachlan Maclean of Morvern.[35][36][37] In the 1630 parliamentary session, Sir Coll Lamont, laird of Lamont, was the commissioner for "Argyll and Tarbert".[38]

There was an Argyllshire constituency of the Parliament of Great Britain from 1708 to 1801, and of the Parliament of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1983 (renamed Argyll in 1950). The Argyll and Bute constituency was created when the Argyll constituency was abolished.

Civil parishes

editCivil parishes are still used for some statistical purposes, and separate census figures are published for them. As their areas have been largely unchanged since the 19th century, this allows for comparison of population figures over an extended period of time.

- Ardchattan and Muckairn

- Ardgour

- Ardrishaig

- Ardnamurchan

- Campbeltown

- Coll

- Colonsay and Oronsay

- Craignish

- Dunoon and Kilmun

- Gigha and Cara Island

- Glassary (Kilmichael), Kilmartin Glen/Lochgilphead[39][40][41]

- Glen Orchy and Inishail

- Inveraray

- Inverchaolain

- Jura

- Kilbrandon and Kilchattan

- Kilcalmonell

- Kilchoman

- Kilchrenan and Dalavich

- Kildalton

- Kilfinan

- Kilfinichen and Kilvickeon

- Killarow and Kilmeny

- Killean and Kilchenzie

- Kilmallie (part)

- Kilmartin

- Kilmodan

- Kilninian and Kilmore

- Kilninver and Kilmelford

- Lismore and Appin

- Lochgilphead

- Lochgoilhead and Kilmorich

- Morvern

- North Knapdale

- Saddell and Skipness

- South Knapdale

- Southend

- Strachur

- Strathlachlan

- Tiree

- Torosay

Settlements

editMainland (north)

editMainland (south)

edit- Achahoish

- Achinhoan

- Achnamara

- Ardentinny

- Ardgartan

- Ardnadam

- Ardrishaig

- Ardtaraig

- Ardulaine

- Arrochar

- Ballachulish

- Barcaldine

- Bellochantuy

- Benderloch

- Blairmore

- Cairndow

- Campbeltown

- Carradale

- Carrick Castle

- Clachaig

- Clachan

- Clachan of Glendaruel

- Claonaig

- Colintraive

- Connel

- Coylet

- Craobh Haven

- Crinan

- Dalavich

- Dalmally

- Dippen

- Drumlemble

- Dumbeg

- Dunoon

- Duror

- Ford

- Furnace

- Glenbarr

- Glenbranter

- Glencoe

- Glendaruel

- Grogport

- Hunters Quay

- Innellan

- Inveraray

- Inverchaolain

- Invercreran

- Kames

- Kennacraig

- Kentallen

- Kilberry

- Kilchenzie

- Kilkerran

- Kilmanshenachan

- Kilmelford

- Kilmore

- Kilmun

- Kinlochleven

- Kirn

- Knipoch

- Largiemore

- Lochgair

- Lochgilphead

- Lochgoilhead

- Machrihanish

- Millhouse

- Muasdale

- North Connel

- Oban

- Ormsary

- Otter Ferry

- Peninver

- Port Ann

- Port Appin

- Portavadie

- Rashfield

- St Catherines

- Saddell

- Sandbank

- Skipness

- Southend

- Stewarton

- Strachur

- Strone

- Succoth

- Tarbert

- Tayinloan

- Taynuilt

- Tayvallich

- Tighnabruaich

- Torinturk

- Torrisdale

- Tullochgorm

- Whistlefield

- Whitehouse

Inner Hebrides

edit- Ardbeg (Islay)

- Ardfernal (Jura)

- Ardilistry (Islay)

- Ardmenish (Jura)

- Ardtalla (Islay)

- Ardtun (Mull)

- Arinagour (Coll)

- Ballygrant (Islay)

- Bowmore (Islay)

- Bridgend (Islay)

- Bruichladdich (Islay)

- Bunessan (Mull)

- Bunnahabhain (Islay)

- Calgary (Mull)

- Craighouse (Jura)

- Craignure (Mull)

- Dervaig (Mull)

- Feolin (Jura)

- Fionnphort (Mull)

- Fishnish (Mull)

- Kilchoman (Islay)

- Kinloch (Rùm)

- Kintra (Mull)

- Knockan (Mull)

- Lagavulin (Islay)

- Laphroaig (Islay)

- Lochbuie (Mull)

- Nerabus (Islay)

- Pennyghael (Mull)

- Port Askaig (Islay)

- Port Charlotte (Islay)

- Port Ellen (Islay)

- Port Mòr (Muck)

- Portnahaven (Islay)

- Port Wemyss (Islay)

- Salen (Mull)

- Scalasaig (Colonsay)

- Scarinish (Tiree)

- Tiroran (Mull)

- Tobermory (Mull)

- Uisken (Mull)

- Ulva Ferry (Mull)

-

Bowmore Round Church, Islay

-

Craighouse, Jura

-

Port Mòr, Muck

Transport

editThe West Highland railway runs through the far north of the county, stopping at Locheilside, Loch Eil Outward Bound, Corpach and Banavie, before carrying on to Mallaig in Inverness-shire. A branch of the line also goes to Oban, calling at Dalmally, Loch Awe, Falls of Cruachan, Taynuilt and Connel Ferry.

Numerous ferries link the islands of the Inner Hebrides to each other and the Scottish mainland. Many of the islands also contain small airstrips enabling travel by air. A fairly extensive bus network links the larger towns of the area, with bus transport also available on the islands of Islay, Jura and Mull.[42]

The county contains a number of small airports which serve the region and Edinburgh/Glasgow: Oban, Tiree, Coll, Colonsay, Campbeltown and Islay.

Kintyre has been one of the mooted locations for a proposed British-Irish bridge; as the closest point to Ireland at first glance it appears to be the most obvious route, however Kintyre is hampered by its remoteness from the main centres of Scotland's population.

Residents

editClans

edit- Clan Campbell was the main clan of this region. The Campbell clan hosted the long line of the Dukes of Argyll.

- Clan MacIntyre historically held lands in this region and had close ties with Clan Campbell.

- Clan Gregor historically held a great deal of lands in this region prior to the proscription of their name in April 1603, the result of a power struggle with the Campbells.

- Clan Lamont historically both allied and feuded with the Campbell clan, culminating in the Dunoon Massacre. In the 19th century, the clan chief sold his lands and relocated to Australia, where the current chief lives.

- Clan McCorquodale held lands around Loch Awe from the early medieval period until the early 18th century. Their seat was a castle on Loch Tromlee.

- Clan MacMillan held lands in Argyll, notably in knapdale (viz. "MacMillan of Knap")

- Clan Malcolm Also known as MacCallum. The Malcolm clan seat is Duntrune Castle on the banks of Loch Crinan

- Clan MacLean Historically held lands on the Isle of Mull with its seat at Duart Castle

- Clan MacLachlan historically feuded with the Campbells, and espoused Jacobitism. Held lands on both sides of Loch Fyne, with its seat in Strathlachlan

- Clan MacEwan historically feuded with the Campbells, cousins of MacLachlans. Held lands in Kilfinan.

Other notable residents

edit- Patrick MacKellar, (1717–1778), born in Argyll, military engineer, achieved his reputation on projects in the United States of America.[43]

- George Robertson, Baron Robertson of Port Ellen (born 12 April 1946, George Islay MacNeill Robertson), British Labour politician and tenth Secretary General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation

- Eric Blair, better known as George Orwell, who resided in the northernmost part of Jura, during the final years of his life (1946–1950). During this period, he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- Karen Matheson, folk singer, grew up in Taynuilt.

- Frances Shand Kydd (née Roche; 20 January 1936 – 3 June 2004) was the mother of Diana, Princess of Wales. She was resident at Ardencaple House on the Island of Seil. She was buried in Pennyfuir Cemetery on the outskirts of Oban.

- Mike Lindup, keyboardist, vocalist and songwriter, noted for being a member of Level 42

In fiction

edit- Rosemary Sutcliff's novel The Mark of the Horse Lord (1965) is set in Earra Gael, i.e. the Coast of the Gael, wherein the Dal Riada undergo an internal struggle for control of royal succession, and an external conflict to defend their frontiers against the Caledones.

- The highlands above the village of Lochgilphead were used for a scene in the 1963 film From Russia with Love, starring Sean Connery as James Bond. He killed two villains in a helicopter by firing gunshots at them.

- The main focus of the song "The Queen of Argyll" is that of a beautiful woman, from Argyll. The song was sung by the band Silly Wizard and covered by Fiddler's Green in 2000.

- The 1985 Scottish movie Restless Natives used Lochgoilhead to film a chase scene, as well as some roads just outside the village.

- The housekeeper Elsie Carson in Julian Fellowes' television drama Downton Abbey is from Argyll.

- In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, after being attacked by Sirius Black, the Fat Lady is found hiding in a map of Argyllshire that is located on the second floor in Hogwarts.

- In Hogwarts Legacy, there is a map on a wall inside the castle above the first floor of the south wing. Using the revelio spell reveals a page for the field guide saying, "This map depicts Argyllshire, a region in Scotland which contains the Hebrides - native home of the Hebrideon dragon."

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Woolf, Alex (2004). "The Age of the Sea-Kings: 900–1300". In Omand, Donald (ed.). The Argyll Book. pp. 94–95.

- ^ Grant, Adrian C. (2024). Fife: Genesis of the Kingdom. Market Harborough: Troubador Publishing. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9781805143840. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Local Government (Scotland) Act 1947, First Schedule" (PDF). legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. p. 231. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Post Office, Great Britain (1911). Post Office Guide. p. 333. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Quarter-inch Administrative Areas Maps: Scotland, Sheet 6, 1968". National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Argyll ScoCnty through time / Population Statistics / Total Population". University of Portsmouth: A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "The History of Argyll and Bute". Argyll and Bute Council. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Macnair, Peter (1914). Argyllshire and Buteshire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 66. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ a b "Argyllshire". Britannica. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Hall, Robert (1887). A Complete Guide to Scotland, for the use of the sportsman and tourist. London: Simpkin Marshall & Co. p. 73.

- ^ Oram, Richard (2004). David I: The King who made Scotland. Stroud: Tempus. p. 48. ISBN 0-7524-2825-X.

- ^ Oliver, Neil (2010). A History of Scotland. London: Orion Books. pp. 88–93. ISBN 9780753826638.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Legislation: Second roll of parliament, 9 February 1293". The Records of the Parliament of Scotland to 1707. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Macnair, Peter (1914). Argyllshire and Buteshire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Chalmers, George (1894). Caledonia. Paisley: Alexander Gardner. p. 148. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Mitchell, Dugald (1886). Tarbert Past and Present. Dumbarton: Bennett & Thomson. p. 45. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Act in favour of lord Lorne, 28 June 1633". Records of the Parliament of Scotland. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Brown, Keith. "Act of the convention of estates of the kingdom of Scotland etc. for a new and voluntary offer to his majesty of £72,000 monthly for the space of twelve months, 23 January 1667". Records of the Parliament of Scotland. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Shennan, Hay (1892). Boundaries of counties and parishes in Scotland as settled by the Boundary Commissioners under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. Edinburgh: W. Green. p. 288. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Ardgour Scottish Parish". A Vision of Britain through Time. GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ Scotland (1925). The Councillor's Manual. p. 113. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Land Mass Coverage Report" (PDF). Registers of Scotland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Argyllshire County Council". Oban Telegraph. 30 May 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ a b Giarchi, George Giacinto (1980). "Between McAlpine and Polaris" (PDF). Glasgow University. p. 232. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Slater's Royal National Commercial Directory of Scotland. 1903. p. 172. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Valuation Rolls of Glassary Parish, 1895, 1905, 1925

- ^ "Lochgilphead, Lochnell Street, Police Station". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Lochgilphead Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan" (PDF). Argyll and Bute Council. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ Valuation Rolls of Glassary Parish, 1925

- ^ "Lochgilphead, Lochnell Street, Regional Council Offices". Canmore. Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Hotel as County Offices". Aberdeen Press and Journal. 13 October 1925. p. 8. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Highlands and Islands Telephone Directory, July 1974, page 5

- ^ "Strathclyde: Argyll and Bute Sub-Region". Daily Record. Glasgow. 4 December 1989. p. 20. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "No. 20236". The Edinburgh Gazette. 17 February 1978. p. 156.

- ^ "1633, 18 June, Edinburgh, Parliament, 1633/6/14". Records of the Parliament of Scotland. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Parliaments of Scotland, 1357–1707" (PDF). Return of the name of every member of the lower house of parliament of England, Scotland, and Ireland, with name of constituency represented, and date of return, from 1213 to 1874; Part II: Great Britain, United Kingdom, Scotland, Ireland. Command papers. Vol. C.69-I. HMSO. 11 August 1879. pp. 539–556. (shows blank pages in Firefox 73, open in Chrome, or download and open)

- ^ Porritt, Edward; Porritt, Annie Gertrude (1903). "Part V: The Scotch Parliamentary System; Chapter XXXV: The Franchise in the Counties". The Unreformed House of Commons. Vol. 2: Scotland and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 78.

- ^ "1630, 28 July, Holyroodhouse, Convention, A1630/7/1". Records of the Parliament of Scotland. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Kilmichael Glassary - British Folklore". britishfolklore.com. 1 December 2023.

- ^ "History". www.historicenvironment.scot.

- ^ "Kilmarnock - Kilspindie | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk.

- ^ "Argyll & Bute Map and Guide" (PDF). 18 May 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963. OCLC 39715719. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

Bibliography

edit- Omand, Donald, ed. (2006). The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-480-0..

Further reading

edit- The Imperial gazetteer of Scotland Vol. I. page 78, by Rev. John Marius Wilson.

External links

edit- Map sources for Argyll

- Visit Scotland, Argyll - Official Webpage

- Map of Argyllshire on Wikishire

- "Filming locations", From Russia with Love (1963), IMDb

- Visitor information for Inveraray, Tarbert, Knapdale, Crinan and Lochgilphead

- Wild about Argyll - Website