Springfield is the capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois and the county seat of Sangamon County. The city's population was 114,394 at the 2020 census, which makes it the state's seventh most-populous city,[10] the second largest outside of the Chicago metropolitan area (after Rockford), and the largest in central Illinois. Approximately 208,000 residents live in the Springfield metropolitan area.[11]

Springfield | |

|---|---|

Downtown Springfield and the Illinois State Capitol | |

| Motto: Home of President Abraham Lincoln[1] | |

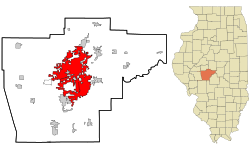

Location in Sangamon County and the state of Illinois | |

| Coordinates: 39°47′54″N 89°40′33″W / 39.79833°N 89.67583°W[3] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Sangamon |

| Townships | Capital, Springfield, Woodside[2] |

| Founded | April 10, 1821[4] |

| Incorporated Town | April 2, 1832[4] |

| City Charter | February 3, 1840[5] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Misty Buscher (R) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 67.49 sq mi (174.79 km2) |

| • Land | 61.16 sq mi (158.41 km2) |

| • Water | 6.33 sq mi (16.38 km2) |

| Elevation | 600 ft (183 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 114,394 |

| • Density | 1,870.37/sq mi (722.16/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | |

| Area code | 217/447 |

| FIPS code | 17-167-11046 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2395940[3] |

| Website | www |

Springfield was settled by European-Americans in the late 1810s, around the time Illinois became a state. The most famous historic resident was Abraham Lincoln, who lived in Springfield from 1837 until 1861, when he went to the White House as President of the United States. Major tourist attractions include multiple sites connected with Lincoln including the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Lincoln Home, Old State Capitol, Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices, and the Lincoln Tomb. Largely on the efforts of Lincoln and other area lawmakers, as well as its central location, Springfield was made the state capital in 1839.

Springfield lies in a valley and plain near the Sangamon River. Lake Springfield, a large reservoir owned by the municipal City Water, Light & Power company (CWLP), provides city residents with recreation and drinking water. Weather is fairly typical for middle latitude locations, with four distinct seasons.

The city has a mayor–council form of government and governs the Capital Township. The government of the state of Illinois is based in Springfield. State government institutions include the Illinois General Assembly, the Illinois Supreme Court and the Office of the Governor of Illinois. There are three public and three private high schools in Springfield. Public schools in Springfield are operated by District No. 186. Springfield's economy is dominated by government jobs, plus the related firms that deal with the state and county governments and justice system, and health care and medicine.

History edit

Pre-Civil War edit

Settlers originally named this community as "Calhoun", after Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, expressing their cultural ties.[12] The land that Springfield now occupies was visited first by trappers and fur traders who came to the Sangamon River in 1818.[13]

The first cabin was built in 1820, by John Kelly, after discovering the area to be plentiful of deer and wild game. He built his cabin upon a hill, overlooking a creek known eventually as the Town Branch. A stone marker on the north side of Jefferson street, halfway between 1st and College streets, marks the location of this original dwelling. A second stone marker at the NW corner of 2nd and Jefferson, often mistaken for the original home site, marks instead the location of the first county courthouse, which was later built on Kelly's property. In 1821, Calhoun was designated as the county seat of Sangamon County due to its location, fertile soil and trading opportunities.

Settlers from Kentucky, Virginia, and North Carolina came to the developing settlement.[13] By 1832, Senator Calhoun had fallen out of the favor with the public and the town renamed itself as Springfield.[14] According to local history, the name was suggested by the wife of John Kelly, after Spring Creek, which ran through the area known as "Kelly's Field".[15]

Kaskaskia was the first capital of the Illinois Territory from its organization in 1809, continuing through statehood in 1818, and through the first year as a state in 1819. Vandalia was the second state capital of Illinois, from 1819 to 1839. Springfield was designated in 1839 as the third capital, and has continued to be so. The designation was largely due to the efforts of Abraham Lincoln and his associates; nicknamed the "Long Nine" for their combined height of 54 feet (16 m).[13][14]

The Potawatomi Trail of Death passed through here in 1838. The Native Americans were forced west to Indian Territory by the government's Indian Removal policy.

Abraham Lincoln arrived in the Springfield area in 1831 when he was a young man, but he did not live in the city until 1837.[16] He spent the ensuing six years in New Salem, where he began his legal studies, joined the state militia, and was elected to the Illinois General Assembly.

In 1837, Lincoln moved to Springfield, where he lived and worked for the next 24 years as a lawyer and politician. Lincoln delivered his Lyceum address in Springfield. His farewell speech when he left for Washington is a classic in American oratory.[16]

Historian Kenneth J. Winkle (1998) examines the historiography concerning the development of the Second Party System (Whigs versus Democrats). He applied these ideas to the study of Springfield, a strong Whig enclave in a Democratic region. He chiefly studied poll books for presidential years. The rise of the Whig Party took place in 1836 in opposition to the presidential candidacy of Martin Van Buren and was consolidated in 1840. Springfield Whigs tend to validate several expectations of party characteristics as they were largely native-born, either in New England or Kentucky, professional or agricultural in occupation, and devoted to partisan organization. Abraham Lincoln's career reflects the Whigs' political rise but, by the 1840s, Springfield began to be dominated by Democratic politicians. Waves of new European immigrants had changed the city's demographics and they became aligned with the Democrats, who made more effort to assist and connect with them. By the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln was barely able to win his home city.[17]

Population edit

Winkle earlier had studied the effect of migration on residents' political participation in Springfield during the 1850s.[18] Widespread migration in the 19th-century United States produced frequent population turnover within Midwestern communities, which influenced patterns of voter turnout and office-holding. Examination of the manuscript census, poll books, and office-holding records reveals the effects of migration on the behavior and voting patterns of 8,000 participants in 10 elections in Springfield. Most voters were short-term residents who participated in only one or two elections during the 1850s. Fewer than 1% of all voters participated in all 10 elections.[18]

Instead of producing political instability, however, rapid turnover enhanced the influence of the more stable residents.[18] Migration was selective by age, occupation, wealth, and birthplace. Longer-term or "persistent" voters, as he terms them, tended to be wealthier, more highly skilled, more often native-born, and socially more stable than non-persisters. Officeholders were particularly persistent and socially and economically advantaged. Persisters represented a small "core community" of economically successful, socially homogeneous, and politically active voters and officeholders who controlled local political affairs, while most residents moved in and out of the city. Members of a tightly knit and exclusive "core community", exemplified by Abraham Lincoln, blunted the potentially disruptive impact of migration on local communities.[18]

Business edit

The case of John Williams illustrates the important role of the merchant banker in the economic development of central Illinois before the Civil War. Williams began his career as a clerk in frontier stores and saved to begin his own business. Later, in addition to operating retail and wholesale stores, he acted as a local banker. He organized a national bank in Springfield. He was active in railroad promotion and as an agent for farm machinery.[19]

Religion edit

During the mid-19th century, the spiritual needs of German Lutherans in the Midwest were not being tended. There had been a wave of migration after the 1848 revolutions, but without a related number of clergy. As a result of the efforts of such missionaries as Friedrich Wyneken, Wilhelm Loehe, and Wilhelm Sihler, additional Lutheran ministers were sent to the Midwest, Lutheran schools were opened, and Concordia Theological Seminary was founded in Ft. Wayne, Indiana in 1846.

The seminary moved to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1869, and then to Springfield in 1874. During the last half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod succeeded in serving the spiritual needs of Midwestern congregations by establishing additional seminaries from ministers trained at Concordia, and by developing a viable synodical tradition.[20]

Civil War to 1900 edit

Springfield became a major center of activity during the American Civil War. Illinois regiments trained there, the first ones under Ulysses S. Grant. He led his soldiers to a remarkable series of victories in 1861–62. The city was a political and financial center of Union support. New industries, businesses, and railroads were constructed to help support the war effort.[14] The war's first official death was a Springfield resident, Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth.

Camp Butler, located seven miles (11 km) northeast of Springfield, Illinois, opened in August 1861 as a training camp for Illinois soldiers. It also served as a camp for Confederate prisoners of war through 1865. In the beginning, Springfield residents visited the camp to take part in the excitement of a military venture, but many reacted sympathetically to mortally wounded and ill prisoners. While the city's businesses prospered from camp traffic, drunken behavior and rowdiness on the part of the soldiers stationed there strained relations. Neither civil nor military authorities proved able to control disorderly outbreaks.[21]

After the war ended in 1865, Springfield became a major hub in the Illinois railroad system. It was a center of government and farming. By 1900 it was also invested in coal mining and processing.[14]

20th century edit

Utopia edit

Local poet Vachel Lindsay's notions of utopia were expressed in his only novel, The Golden Book of Springfield (1920), which draws on ideas of anarchistic socialism in projecting the progress of Lindsay's hometown toward utopia.[22]

The Dana–Thomas House is a Frank Lloyd Wright design built in 1902–03. Wright began work on the house in 1902. Commissioned by Susan Lawrence Dana, a local patron of the arts and public benefactor, Wright designed a house to harmonize with the owner's devotion to the performance of music. Coordinating art glass designs for 250 windows, doors, and panels as well as over 200 light fixtures, Wright enlisted Oak Park artisans. The house is a radical departure from Victorian architectural traditions. Covering 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2), the house contained vaulted ceilings and 16 major spaces. As the nation was changing, so Wright intended this structure to reflect the changes. Creating an organic and natural atmosphere, Wright saw himself as an "architect of democracy" and intended his work to be a monument to America's social landscape.[23]

It is the only historic site later acquired by the state exclusively because of its architectural merit. The structure was opened to the public as a museum house in September 1990; tours are available, 9:00 a.m.–4:00 p.m. Wednesdays through Sundays.[23][24][25]

1908 race riot edit

Sparked by the alleged rape of a white woman by a black man and the murder of a white engineer, supposedly also by a black man, in Springfield, and reportedly angered by the high degree of corruption in the city, rioting broke out on August 14, 1908, and continued for three days in a period of violence known as the Springfield race riot. Gangs of white youth and blue-collar workers attacked the predominantly black areas of the city known as the Levee district, where most black businesses were located, and the Badlands, where many black residences stood. At least sixteen people died as a result of the riot: nine black residents, and seven white residents who were associated with the mob, five of whom were killed by state militia and two committed suicide. The riot ended when the governor sent in more than 3,700 militiamen to patrol the city, but isolated incidents of white violence against blacks continued in Springfield into September.[26]

21st century edit

On March 12, 2006, two F2 tornadoes hit the city, injuring 24 people, damaging hundreds of buildings, and causing $150 million in damages.[27]

On February 10, 2007, then-senator Barack Obama announced his presidential candidacy in Springfield, standing on the grounds of the Old State Capitol.[28] Senator Obama also used the Old State Capitol in Springfield as a backdrop when he announced Joe Biden as his running mate on August 23, 2008.

Geography edit

Located within the central section of Illinois, Springfield is 80 miles (130 km) northeast of St. Louis. The Champaign/Urbana area is to the east, Peoria is to the north, and Bloomington–Normal is to the northeast. Decatur is 40 miles (64 km) due east.

Topography edit

The city is at an elevation of 558 feet (170 m) above sea level.[3] According to the 2010 census, Springfield has a total area of 65.764 square miles (170.33 km2), of which 59.48 square miles (154.05 km2) (or 90.44%) is land and 6.284 square miles (16.28 km2) (or 9.56%) is water.[29] The city is located in the Lower Illinois River Basin, in a large area known as Till Plain. Sangamon County, and the city of Springfield, are in the Springfield Plain subsection of Till Plain. The Plain is underlain by glacial till that was deposited by a large continental ice sheet that repeatedly covered the area during the Illinoian Stage.[30][31]

The majority of the Lower Illinois River Basin is flat, with relief extending no more than 20 feet (6.1 m) in most areas, including the Springfield subsection of the plain. The differences in topography are based on the age of drift. The Springfield and Galesburg Plain subsections represent the oldest drift, Illinoian, while Wisconsinian drift resulted in end moraines on the Bloomington Ridged Plain subsection of Till Plain.[32]

Lake Springfield is a 4,200-acre (1,700 ha) human-made reservoir owned by City Water, Light & Power,[33] the largest municipally owned utility in Illinois.[34] It was built and filled in 1935 by damming Lick Creek, a tributary of the Sangamon River which flows past Springfield's northern outskirts.[35] The lake is used primarily as a source for drinking water for the city of Springfield, also providing cooling water for the condensers at the power plant on the lake. It attracts approximately 600,000 visitors annually and its 57 miles (92 km) of shoreline is home to over 700 lakeside residences and eight public parks.[33]

The term "full pool" describes the lake at 560 feet (170 m) above sea level and indicates the level at which the lake begins to flow over the dam's spillway, if no gates are opened.[35] Normal lake levels are generally somewhere below full pool, depending upon the season. During the drought from 1953 to 1955, lake levels dropped to their historical low, 547.44 feet (166.86 m) AMSL.[35] The highest recorded lake levels were in December 1982, when the lake crested at 564 feet (172 m).[35]

Climate edit

Under the Köppen climate classification, Springfield falls within either a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa) if the 0 °C (32 °F) isotherm is used or a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) if the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm is used. In recent years, winter temperatures have increased substantially while summer temperatures have remained mostly the same. Hot, humid summers and cold, rather snowy winters are the norm. Springfield is located on the farthest reaches of Tornado Alley, and as such, thunderstorms are a common occurrence throughout the spring and summer. From 1961 to 1990 the city of Springfield averaged 35.25 inches (895 mm) of precipitation per year.[36] During that same period the average yearly temperature was 52.4 °F (11.3 °C), with a summer maximum of 76.5 °F (24.7 °C) in July and a winter minimum of 24.2 °F (−4.3 °C) in January.[37]

From 1971 to 2000, NOAA data showed that Springfield's annual mean temperature increased slightly to 52.7 °F (11.5 °C). During that period, July averaged 76.3 °F (24.6 °C), while January averaged 25.1 °F (−3.8 °C).

From 1981 to 2010, NOAA data showed that Springfield's annual mean temperature increased slightly to 53.1 °F (11.7 °C). During that period, July averaged 76.0 °F (24.4 °C), while January averaged 26.9 °F (−2.8 °C).

On June 14, 1957, a tornado hit Springfield, killing two people.[27] On March 12, 2006, the city was struck by two F2 tornadoes.[27] The storm system which brought the two tornadoes hit the city around 8:30pm; no one died as a result of the weather.[27] Springfield received a federal grant in February 2005 to help improve its tornado warning systems and new sirens were put in place in November 2006 after eight of the sirens failed during an April 2006 test, shortly after the tornadoes hit.[38][39][40] The cost of the new sirens totaled $983,000.[38] Although tornadoes are not uncommon in central Illinois, the March 12 tornadoes were the first to hit the actual city since the 1957 storm.[27] The 2006 tornadoes followed nearly identical paths to that of the 1957 tornado.[27]

| Climate data for Springfield, Illinois (Abraham Lincoln Capital Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1879–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

80 (27) |

91 (33) |

90 (32) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

112 (44) |

108 (42) |

102 (39) |

93 (34) |

83 (28) |

74 (23) |

112 (44) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.1 (14.5) |

63.8 (17.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

83.5 (28.6) |

89.5 (31.9) |

93.8 (34.3) |

94.5 (34.7) |

94.4 (34.7) |

91.9 (33.3) |

85.8 (29.9) |

72.0 (22.2) |

62.3 (16.8) |

96.5 (35.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 35.9 (2.2) |

41.1 (5.1) |

53.1 (11.7) |

65.6 (18.7) |

75.7 (24.3) |

84.0 (28.9) |

86.8 (30.4) |

85.4 (29.7) |

80.2 (26.8) |

67.4 (19.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

40.7 (4.8) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

32.4 (0.2) |

43.2 (6.2) |

54.4 (12.4) |

65.1 (18.4) |

73.7 (23.2) |

76.5 (24.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

68.0 (20.0) |

56.0 (13.3) |

43.5 (6.4) |

32.9 (0.5) |

54.0 (12.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

33.2 (0.7) |

43.3 (6.3) |

54.4 (12.4) |

63.3 (17.4) |

66.2 (19.0) |

64.3 (17.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

44.6 (7.0) |

34.2 (1.2) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

44.0 (6.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −4.2 (−20.1) |

2.4 (−16.4) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

38.1 (3.4) |

49.4 (9.7) |

54.5 (12.5) |

52.4 (11.3) |

39.6 (4.2) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

16.3 (−8.7) |

4.1 (−15.5) |

−8.4 (−22.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−24 (−31) |

−12 (−24) |

16 (−9) |

28 (−2) |

39 (4) |

48 (9) |

43 (6) |

31 (−1) |

13 (−11) |

−3 (−19) |

−21 (−29) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.03 (52) |

1.93 (49) |

2.76 (70) |

3.97 (101) |

4.52 (115) |

4.61 (117) |

3.85 (98) |

3.37 (86) |

2.86 (73) |

3.26 (83) |

2.71 (69) |

2.15 (55) |

38.04 (966) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.7 (17) |

6.1 (15) |

3.1 (7.9) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.2 (3.0) |

4.3 (11) |

21.8 (55) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.7 | 8.9 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 12.6 | 10.6 | 8.5 | 8.2 | 7.3 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 114.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.2 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 16.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.4 | 74.0 | 71.3 | 65.3 | 65.6 | 66.6 | 70.4 | 74.0 | 71.9 | 68.4 | 73.8 | 77.6 | 71.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 160.7 | 158.7 | 186.5 | 225.8 | 281.2 | 308.0 | 320.7 | 291.0 | 248.4 | 214.0 | 140.2 | 129.3 | 2,664.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 53 | 53 | 50 | 57 | 63 | 69 | 70 | 68 | 66 | 62 | 47 | 44 | 60 |

| Source: NOAA (sun and humidity 1961–1990)[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape edit

Springfield proper is largely based on a grid street system, with numbered streets starting with the longitudinal First Street (which leads to the Illinois State Capitol) and leading to 32nd Street in the far eastern part of the city. Previously, the city had four distinct boundary streets: North, South, East, and West Grand Avenues. Since expansion, West Grand Avenue became MacArthur Boulevard and East Grand became 19th Street on the north side and 18th Street on the south side. 18th Street has since been renamed after Martin Luther King Jr.[44] North and South Grand Avenues (which run east–west) have remained important corridors in the city. At South Grand Avenue and Eleventh Street, the old "South Town District" lies, with the City of Springfield undertaking a significant redevelopment project there.

Latitudinal streets range from names of presidents in the downtown area to names of notable people in Springfield and Illinois to names of institutions of higher education, especially in the Harvard Park neighborhood.

Springfield has at least twenty separately designated neighborhoods, though not all have neighborhood associations. They include: Benedictine District, Bunn Park, Downtown, Eastsview, Enos Park, Glen Aire, Harvard Park, Hawthorne Place, Historic West Side, Lincoln Park, Mather and Wells, Medical District, Near South, Northgate, Oak Ridge, Old Aristocracy Hill, Pillsbury District, Shalom, Springfield Lakeshore, Toronto, Twin Lakes, UIS Campus, Victoria Lake, Vinegar Hill, and Westchester neighborhoods.[45]

The Lincoln Park Neighborhood is an area bordered by 3rd Street on its west, Black Avenue on the north, 8th street on the east and North Grand Avenue. The neighborhood is not far from Lincoln's Tomb on Monument Avenue.[46]

Springfield completely surrounds four suburbs that have their own municipal governments: Jerome, Leland Grove, Southern View, and Grandview. It also surrounds various unincorporated enclaves, including the neighborhoods of Laketown and Cabbage Patch.[47]

Demographics edit

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 2,579 | — | |

| 1850 | 4,533 | 75.8% | |

| 1860 | 9,320 | 105.6% | |

| 1870 | 17,364 | 86.3% | |

| 1880 | 19,743 | 13.7% | |

| 1890 | 24,963 | 26.4% | |

| 1900 | 34,159 | 36.8% | |

| 1910 | 51,678 | 51.3% | |

| 1920 | 59,183 | 14.5% | |

| 1930 | 71,864 | 21.4% | |

| 1940 | 75,503 | 5.1% | |

| 1950 | 81,628 | 8.1% | |

| 1960 | 83,271 | 2.0% | |

| 1970 | 91,753 | 10.2% | |

| 1980 | 99,637 | 8.6% | |

| 1990 | 105,227 | 5.6% | |

| 2000 | 111,454 | 5.9% | |

| 2010 | 116,250 | 4.3% | |

| 2020 | 114,394 | −1.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[48] | |||

2020 census edit

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[49] | Pop 2010[50] | Pop 2020[51] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 89,510 | 86,781 | 77,775 | 80.31% | 74.65% | 67.99% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 17,007 | 21,344 | 23,126 | 15.26% | 18.36% | 20.22% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 203 | 205 | 191 | 0.18% | 0.18% | 0.17% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 1,612 | 2,538 | 3,327 | 1.45% | 2.18% | 2.91% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 30 | 23 | 42 | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.04% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 204 | 221 | 455 | 0.18% | 0.19% | 0.40% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 1,551 | 2,813 | 5,896 | 1.39% | 2.42% | 5.15% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 1,337 | 2,325 | 3,582 | 1.20% | 2.00% | 3.13% |

| Total | 111,454 | 116,250 | 114,394 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

At the 2010 Census, 75.8% of the population was White, 18.5% Black or African American, 0.2% American Indian and Alaska Native, 2.2% Asian, and 2.6% of two or more races. 2.0% of Springfield's population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (they may be of any race).[10] Non-Hispanic Whites were 74.7% of the population in 2010,[10] down from 87.6% in 1980.[52]

As of the census[53] of 2000,[needs update] there were 111,454 people, 48,621 households, and 27,957 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,063.9 people per square mile (796.9 people/km2). There were 53,733 housing units at an average density of 995.0 per square mile (384.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 81.0% White, 15.3% African American, 0.2% Native American, 1.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.5% from other races, and 1.5% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.2% of the population.

There were 48,621 households, out of which 27.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.1% were married couples living together, 12.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.5% were non-families. 36.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.94.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.0% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 23.0% from 45 to 64, and 14.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $39,388, and the median income for a family was $51,298. Families with children had a higher income of about $69,437. Males had a median income of $36,864 versus $28,867 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,324. About 8.4% of families and 11.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.3% of those under age 18 and 7.7% of those age 65 or over.

Economy edit

Many of the jobs in the city center around state government, headquartered in Springfield. As of 2002, the State of Illinois is both the city and county's largest employer, employing 17,000 people across Sangamon County.[54] As of February 2007, government jobs, including local, state and county, account for about 30,000 of the city's non-agricultural jobs.[55] Trade, transportation and utilities, and the health care industries each provide between 17,000 and 18,000 jobs to the city.[55] The largest private sector employer in 2002 was Memorial Health System with 3,400 people working for the organization.[54] According to estimates from the "Living Wage Calculator" the living wage for the city of Springfield is $7.89 per hour for one adult,[56] approximately $15,780 working 2,000 hours per year. For a family of four, costs are increased and the living wage is $17.78 per hour within the city.[56] According to the United States Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the Civilian Labor force dropped from 116,500 in September 2006 to 113,400 in February 2007. In addition, the unemployment rate rose during the same time period from 3.8% to 5.1%.[55]

Largest employers edit

According to the city's 2021 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[57] the largest employers in the city are:

| No. | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Illinois | 17,800 |

| 2 | Memorial Health System | 5,238 |

| 3 | Hospital Sisters Health System | 4,434 |

| 4 | Springfield Clinic | 2,449 |

| 5 | Springfield Public Schools | 2,130 |

| 6 | University of Illinois Springfield | 1,642 |

| 7 | Southern Illinois University School of Medicine | 1,470 |

| 8 | City of Springfield | 1,410 |

| 9 | Horace Mann Educators Corporation | 1,066 |

| 10 | BlueCross BlueShield | 900 |

Arts and culture edit

Springfield has been home to a wide array of individuals, who, in one way or another, contributed to the broader American culture. Wandering poet Vachel Lindsay, most famous for his poem "The Congo" and a booklet called "Rhymes to be Traded for Bread", was born in Springfield in 1879.[58] At least two notable people affiliated with American business and industry have called the Illinois state capital home at one time or another. Both John L. Lewis, a labor activist, and Marjorie Merriweather Post, the founder of the General Foods Corporation, lived in the city; Post in particular was a native of Springfield.[59][60] In addition, astronomer Seth Barnes Nicholson was born in Springfield in 1891.[61]

A Madeiran Portuguese community resided in the vicinity of the Carpenter Street Underpass, one of the earliest and largest Portuguese settlements in the Midwest. The Portuguese immigrants that originated the community left Madeira because they experienced social ostracization due to being Protestants in their largely Catholic homeland, having been converted to Protestantism by a Scottish reverend named Robert Reid Kalley, who visited Madeira in 1838.[62] These Protestant Madeiran exiles relocated to the Caribbean island of Trinidad before settling permanently in Springfield in 1849.[62] By the early twentieth century, these immigrants resided in the western extension of a neighborhood known as the "Badlands". The Badlands was included in the widespread destruction and violence of the Springfield Race Riot in August 1908, an event that led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The Carpenter Street archaeological site possesses local and national significance for its potential to contribute to an understanding of the lifestyles of multiple ethnic/racial groups in Springfield during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[63]

Literary tradition edit

Springfield and the Sangamon Valley enjoy a strong literary tradition in Abraham Lincoln, Vachel Lindsay, Edgar Lee Masters, John Hay, William H. Herndon, Benjamin P. Thomas, Paul Angle, Virginia Eiffert, Robert Fitzgerald and William Maxwell, among others. The Illinois State Library's Gwendolyn Brooks Building features the names of 35 Illinois authors etched on its exterior fourth floor frieze. Through the Illinois Center for the Book, a comprehensive resource on authors, illustrators, and other creatives who have published books who have written about Illinois or lived in Illinois is maintained.[64]

Performing arts edit

The Hoogland Center for the Arts in downtown Springfield is a centerpiece for performing arts, and houses among other organizations the Springfield Theatre Centre, the Copper Coin Ballet Company, and the Springfield Municipal Opera, also known as The Muni, which stages community theatre productions of Broadway musicals outdoors each summer. Before being purchased and renamed, the Hoogland Center was Springfield's Masonic Temple. Prior to the Hoogland, the Springfield Theatre Centre was housed in the nearby Legacy Theatre. Sangamon Auditorium, located on the campus of the University of Illinois Springfield also serves as a larger venue for musical and performing acts, both touring and local.

A few films have been created or had elements of them created in Springfield. Legally Blonde 2: Red, White & Blonde was filmed in Springfield in 2003.

Musicians Artie Matthews and Morris Day both once called Springfield home.[65][66]

Springfield is also home to long-running underground all-ages space The Black Sheep Cafe.[67]

Festivals edit

Springfield is home to the annual Springfield Old Capitol Art Fair, a spring festival held annually in the third weekend in May.[68] Since 2002, Springfield has also hosted the 'Route 66 Film Festival', set to celebrate films routed in, based on, or taking part on the famous Route 66.[69][70]

Tourism edit

Springfield is known for some popular food items: the corn dog is claimed to have been invented in the city under the name "Cozy Dog", although there is some debate to the origin of the snack.[71][72] The horseshoe sandwich, not well known outside of central Illinois, also originated in Springfield.[73] Springfield was once the site of the Reisch Beer brewery, which operated for 117 years under the same name and family from 1849 to 1966.[74]

The Maid-Rite Sandwich Shop in Springfield still operates what it claims as the first U.S. drive-thru window.[75] The city is also known for its chili, or "chilli", as it is known in many chili shops throughout Sangamon County.[76] The unique spelling is said to have begun with the founder of the Dew Chilli Parlor in 1909, due to a spelling error in its sign.[77] Another interpretation is that the misspelling represented the "Ill" in the word Illinois.[77] In 1993, the Illinois state legislature adopted a resolution proclaiming Springfield the "Chilli Capital of the Civilized World".[76]

Springfield is dotted with sites associated with U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, who started his political career there.[78] These include the Lincoln Home National Historic Site, a National Historical Park that includes the preserved surrounding neighborhood; the Lincoln-Herndon Law Offices State Historic Site, the Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site, the Old State Capitol State Historic Site, the Lincoln Depot, from which Abraham Lincoln departed Springfield to be inaugurated in Washington, D.C.; the Elijah Iles House, Edwards Place and the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. The church that the Lincoln family belonged to, First Presbyterian Church, still has the original Lincoln family pew on display in its narthex. Near the village of Petersburg, is New Salem State Park, a restored hamlet of log cabins. This is a reconstruction of the town where Lincoln lived as a young man. With the opening of the Presidential Library and Museum in 2004, the city has attracted numerous prominent visitors, including Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, the actor Liam Neeson, and the Emir of Qatar.[79][80]

The Donner Party, a group of pioneers who resorted to cannibalism while snowbound during a winter in the Sierra Nevada mountains, began their journey West from Springfield.[81] Springfield's Dana–Thomas House is among the best preserved and most complete of Frank Lloyd Wright's early "Prairie" houses.[82] It was built in 1902–1904 and has many of the furnishings Wright designed for it.[82] Springfield's Washington Park is home to Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon and the site of a carillon festival, held annually since 1962.[83] In August, the city is the site of the Illinois State Fair at the Illinois State Fairgrounds.

Although not born in Springfield, Lincoln is the city's most famous resident. He lived there for 24 years.[16] The only home he ever owned is open to the public, seven days a week, free of charge, and operated by the National Park Service.[16]

Springfield has the area's largest amusement park, Knight's Action Park and Caribbean Water Park, which is open from May to September. The park also features and operates the city's only remaining drive-in theater, the Route 66 Twin Drive-In.

Sports edit

| team | League | Sport | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Springfield A.S.C | USL League Two | Association football | Sacred Heart-Griffin High School | 2021 | 0 |

| Springfield FC | Midwest Premier League | Association football | SASA Soccer Complex | 2011 | 0 |

| Springfield Lucky Horseshoes | Prospect League | Baseball | Robin Roberts Stadium | 2008 | 1 |

| Springfield Jr. Blues | North American Hockey League | Ice Hockey | Nelson Center | 1993 | 2 |

| Capital City Hooligans | Men's Roller Derby Association | Men's Roller Derby | Skateland South | 2012 | N/A |

Historically, Springfield has been home to a number of minor league baseball franchises, the latest club, the college-prep Springfield Sliders, arriving in the city in 2008. In the 1948 baseball season, Springfield was also home to an All-American Girls Professional Baseball League team, the Springfield Sallies, but the team's lackluster performance led them to be folded in with the Chicago Colleens as rookie development teams the following year.

The city was the home of the Springfield Stallions, an indoor football team who played at the Prairie Capital Convention Center in 2007. Today, the city is host to the Springfield Jr. Blues, a North American Hockey League team that plays at the Nelson Recreation Center. The city is also a host to several Semi Pro Football Teams. The oldest organization is the Capital City Outlaws, which was established in 1992. The Outlaws which played 11 man football, most recently in The Midwest Football League until 2004, switched to an 8-man Semi Pro Football League (8FL) in 2004. The Sangamon County Seminoles became an expansion team in the 8FL in 2008. A newly formed team in 2010, the Springfield Foxes, play in the Mid States Football League (MSFL) (11 man). The Foxes were league runners-up in the MSFL League Championship in 2012.

The city has produced several notable professional sports talents. Current and former Major League Baseball players Kevin Seitzer, Jeff Fassero, Ryan O'Malley, Jason and Justin Knoedler, and Hall of Famer Robin Roberts were all born in Springfield.[84][85][86][87] Springfield's largest baseball field, Robin Roberts Stadium at Lanphier Park, takes its full name in honor of Roberts and his athletic achievements. Former MLB player Dick "Ducky" Schofield is currently an elected official in Springfield, and his son Dick also played in the Major Leagues, as does Ducky's grandson, Jayson Werth. Ducky, Dick, and Jayson were all born in Springfield. Ducky's daughter (and Jayson's mother) Kim Schofield Werth, also from Springfield, is a track star who competed in the U.S. Olympic Trials. National Basketball Association players Dave Robisch, Kevin Gamble, and Andre Iguodala are all from the city.[88][89] Long-time NFL announcer (NBC) and former Cincinnati Bengal Pro Bowl tight end Bob Trumpy is a city native, having graduated from Springfield High School. Former NFL wide receiver Otto Stowe was a 1967 graduate of the now-defunct Feitshans High School. A UFC fighter, Matt Mitrione, attended and played football for Sacred Heart Griffin. He also played in the NFL as an undrafted free agent.

At the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Springfield native Ryan Held won a gold medal as a member of the USA 400-meter (4 X 100 meter) freestyle relay team along with Caeleb Dressel, Michael Phelps, and Nathan Adrian. During his senior year at Sacred-Heart Griffin High School in 2014, Held was named Illinois State Swimmer of the Year.[90]

Parks and recreation edit

The Springfield Park District operates more than 30 parks throughout the city. The two best-known are Carpenter Park, an Illinois Nature Preserve on the banks of the Sangamon River, and Washington Park and Botanical Garden on the city's southwest side and adjacent to some of Springfield's most beautiful and architecturally interesting homes. Washington Park has also been home to the Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon since its dedication in 1962. Southwind Park, on the southern edge of the city, has been developed as a park enjoying full compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Lincoln Park, located next to Oak Ridge Cemetery where President Lincoln's tomb is located, is home to the Nelson Recreation Center, which boasts a public swimming pool, tennis courts, and the city's only public ice rink, home of the Springfield Junior Blues, a minor league hockey team. Centennial Park, which rests on the outskirts of Springfield's southwest limits, holds the city's only public skatepark, as well as several ball fields, tennis courts, and a manmade hill for cardio exercises and sledding in winter months.

In addition to the public-sector parks operated by the Springfield Park District, two significant privately operated tree gardens/arboretums operate within city limits: the Abraham Lincoln Memorial Garden on Lake Springfield south of the city, and the Adams Wildlife Sanctuary on Springfield's east side.

Government edit

Springfield city government is structured under the mayor-council form of government. It is the strong mayor variation of that type of municipal government, the mayor holds executive authority, including veto power, in Springfield.[91] The executive branch also consists of 17 non-elected city "offices". Ranging from the police department to the Office of Public Works, each office can be altered through city ordinance.[91]

Elected officials in the city, mayor, aldermen, city clerk, and treasurer, serve four-year terms.[92] The elections are not staggered.[92] The council members are elected from ten districts throughout the city while the mayor, city clerk and city treasurer are elected on an at-large basis.[92] The council, as a body, consists of the ten aldermen and the mayor, though the mayor is generally a non-voting member who only participates in the discussion.[93] There are a few instances where the mayor does vote on ordinances or resolutions: if there is a tie vote, if more than half of the aldermen support the motion, whether there is a tie or not, and where a vote greater than the majority is required by the municipal code.[93]

Members edit

City elections are technically non partisan, however most candidates are affiliated with a political party.[94] As such, party affiliation is a matter of self identification.

| Citywide positions | Officeholder | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Mayor | Misty Buscher | Republican |

| Treasurer | Colleen Redpath Feger | Republican |

| Clerk | Frank Lesko | Republican |

| City council | Officeholder | Party |

| Ward 1 | Chuck Redpath | Republican |

| Ward 2 | Shawn Gregory | Democratic |

| Ward 3 | Roy Williams Jr. | Democratic |

| Ward 4 | Larry Rockford | Unknown |

| Ward 5 | Lakeisha Purchase | Democratic |

| Ward 6 | Jennifer Notariano | Democratic |

| Ward 7 | Brad Carlson | Republican |

| Ward 8 | Erin Conley | Democratic |

| Ward 9 | Jim Donelean | Democratic |

| Ward 10 | Ralph Hanauer | Republican |

State government edit

As the state capital, Springfield is home to the three branches of Illinois government. Much like the United States federal government, Illinois government has an executive branch, occupied by the state governor, a legislative branch, which consists of the state senate and house, and a judicial branch, which is topped by the Illinois Supreme Court.[97] The Illinois legislative branch is collectively known as the Illinois General Assembly.[98] Many state bureaucrats work in offices in Springfield, and it is the regular meeting place of the Illinois General Assembly.[99] All persons elected on a statewide basis are required to have at least one residence in Springfield, and the state government funds these residents.[100]

As of 2020[update] none of the major constitutional officers in Illinois designated Springfield as their primary residence; most cabinet officers and all major constitutional officers instead primarily do their business in Chicago. A former director of the Southern Illinois University Paul Simon Institute for Public Affairs, Mike Lawrence, stated that many of the elected officials in Illinois "spend so little time in Springfield".[100] In 2012 St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist Pat Gauen argued that "in the reality of Illinois politics, [Springfield] shares de facto capital status with Chicago." Gauen noted that several elected officials such as the Governor, as well as the Attorney General, Speaker of the House, the minority leader of the House, President of the Senate, the minority leader of the Senate, the Comptroller, and the Treasurer, all live in the Chicago area. According to Gauen, "Everybody who's anybody in Illinois government has an office in Chicago"; most state officials work from the James R. Thompson Center in the Chicago Loop. He added that at one point in 2011, Governor Pat Quinn only spent 68 days and 40 nights in Springfield as per his official schedule.[99] University of Illinois researcher and former member of the Illinois legislature Jim Nowlan stated "It's almost like Chicago is becoming the shadow capital of Illinois" and that "Springfield is almost become a hinterland outpost."[100] Lawrence criticized the fact that state officials spent little time in Springfield since it estranged them from and devalued Illinois state employees based in that city.[100]

According to Gauen, "Illinois seems rather unlikely to move its official capital to Chicago".[99]

Townships edit

The Capital Township formed from Springfield Township on July 1, 1877, and was established and named by the Sangamon County Board on March 6, 1878. The limits of the township and City of Springfield were made co-extensive on February 17, 1892, but are no longer so with subsequent annexation by the City of Springfield. There are three functions of this township: assessing property, collection first property tax payment, and assisting residents that live in the township. One thing that makes the Capital township unique is that the township never has to raise taxes for road work, since the roads are maintained by the Springfield Department of Public Works.[101][102]

In the 21st century Springfield annexed large parts of Springfield and Woodside townships. The annexed parcels remained part of their original townships despite being within the Springfield city limits.[2]

Law enforcement edit

The Springfield Police Department was founded in 1840 as part of the city charter. As of 2020, the police chief was Kenneth Scarlette and the department had 242 employees.

Springfield Police officer Samuel Rosario was arrested by the Illinois State Police on February 28, 2017, after fighting with a teenager on charges of official misconduct and battery. He was found guilty of official misconduct in August 2019.[103]

Education edit

Springfield is currently home to six public and private high schools.

The Springfield public school district is District No. 186. District 186 operates 24 elementary schools and an early learning center, (pre-K). District 186 operates three high schools, Lanphier High School, Springfield High School and Springfield Southeast High School, which replaced Feitshans High School in 1967, and five middle schools.[104]

Springfield's Sacred Heart-Griffin High School is a city Catholic high school.[105] Other area high schools include Calvary Academy and Lutheran High School.[106] Ursuline Academy was a second Catholic high school founded in 1857, first as an all-girls school, and converted to co-ed in 1981. The school was closed in 2007.

Springfield hosts one University. The University of Illinois Springfield (UIS, formerly Sangamon State University), which is located on the southeast side of the city.

Springfield is also home to a junior college Lincoln Land Community College, located just south of UIS. From 1875 to 1976, Springfield was also home to Concordia Theological Seminary. The seminary was moved back to its original home of Fort Wayne, Indiana, and the campus now serves as the Illinois Department of Corrections Academy.

The city is home to the Springfield campus of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine,[107] which includes a Cancer Institute in Springfield's Medical District.[108]

Media edit

The State Journal-Register is the primary daily newspaper for Springfield, and its surrounding area. The newspaper was founded in 1831 as the Sangamon Journal, and claims to be "the oldest newspaper in Illinois".[109] The local alternative weekly is the Illinois Times.

Television stations edit

Springfield is part of the Springfield-Decatur-Champaign TV market.[110] Four TV stations broadcast from the Springfield area: WCIX MYTV 49, WICS ABC 20, WRSP FOX 55, and WSEC PBS 14. Both WICS and WRSP are currently owned by the same parent company Sinclair Broadcast Group. Springfield is also served by two stations in Decatur, WAND NBC 17 and WBUI CW 23, and two stations in Champaign, WCIA CBS 3 and WILL PBS 12. One television station that has since ceased to exist was WJJY-TV, which operated in the Springfield area for three years (1969–1971).[111]

Radio stations edit

The following radio stations broadcast in the Springfield area:[112][113]

Infrastructure edit

Health systems edit

There are two Springfield hospitals, Memorial Medical Center and St. John's Hospital. A third hospital, originally Springfield Community Hospital, and later renamed Doctor's Hospital operated on Springfield's south side until 2003.[114] Kindred Healthcare opened a long term acute care hospital in Springfield in 2010, however, the facility was purchased by Vibra Healthcare in 2013, and was operated by Vibra under the name Vibra Hospital of Springfield[115] until it closed in 2019.[116]

St. John's Hospital is home to the Prairie Heart Institute, which performs more cardiovascular procedures than any other hospital in Illinois.[117] The dominant health care providers in the area are SIU HealthCare and Springfield Clinic. The major medical education center in the area is the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. The major regional cancer center is the SIU Simmons Cancer Institute.

Public utilities edit

The owner of Lake Springfield – City Water, Light & Power – supplies electric power generated from the Dallman Power Plants to the city of Springfield and eight surrounding communities. The company also provides these cities and towns with water from the lake. In 2005, ground was broken for a third municipally-owned power plant, which came online in 2009. Natural gas is provided via Ameren Illinois, formerly Central Illinois Light Company (CILCO).[118]

Transportation edit

Interstate 55 runs from north to south past Springfield, while I-72, which is concurrent with U.S. Route 36 from the Missouri state line to Decatur, runs from east to west.

Amtrak serves Springfield daily with its Lincoln Service and Texas Eagle routes. Service consists of four Lincoln Service round-trips between Chicago and St. Louis, and one Texas Eagle round-trip between San Antonio and Chicago. Three days a week, the Eagle continues on to Los Angeles.[119] Springfield is served by the following freight railroads: Canadian National, Illinois and Midland Railroad, Kansas City Southern, Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific. Springfield is also served by Greyhound buses at a station on North Dirksen Parkway.

Local mass transportation needs are met by a bus service. The Sangamon Mass Transit District (SMTD) operates Springfield's bus system.[120] The city also lies along historic Route 66.

Border thoroughfare traffic is handled by Veterans Parkway and J. David Jones Parkway on the west side, Everett M. Dirksen Parkway on the east side, Sangamon Avenue on the north end, and Wabash Avenue, Stanford Avenue, and Adlai Stevenson Drive on the south end. The far south corridor is served by Toronto and Woodside Roads. Thoroughfare traffic through the heart of the city is provided by a series of one-way streets. Fifth and Sixth Streets serve the bulk of the north–south traffic, with Fourth and Seventh Streets serving additional traffic between North Grand and South Grand Avenues. East–west traffic is handled by Jefferson Street, entering Springfield on the west side from IL 97, and then splitting into a pair of one-way streets at Amos Avenue (Madison eastbound and Jefferson westbound). The two converge again after Eleventh Street to become Clearlake Avenue, which in turn converges into I-72 eastbound just past Dirksen Parkway. Additional east–west one-way streets run through the downtown areas of Springfield, including Monroe, Adams, Washington, and Cook Streets, as well as a stretch of Lawrence Avenue.

Abraham Lincoln Capital Airport serves the capital city with scheduled passenger jet service to Chicago O'Hare, Fort Myers (via the Punta Gorda Airport) and Orlando (via the Sanford Airport).[121]

Springfield and the surrounding metropolitan area has constructed bike trails and bike lanes on a number of streets. Currently four main trails exist; two significant paved trails, the Interurban Trail and the Lost Bridge Trail, serve Springfield and its suburbs of Chatham, Illinois and Rochester, Illinois respectively. The Lost Bridge Trail has been extended further into Springfield by the Bunn to Lost Bridge Trail, which follows a stretch of Ash Street and Taylor Avenue. Plans are to extend it further still to Stanford Avenue.[122] A third trail, the Wabash Trail, extends westward from the northern end of the Interurban Trail toward Parkway Pointe, a regional shopping destination.

The fourth trail is a section, opened in July 2011, of the Sangamon Valley Trail spanning north to south through the west central part of Sangamon County. The section open as of 2011 extends northward from Centennial Park to Stuart Park.[123] This trail, if completed in its entirety, will reuse the entire Sangamon County portion of the abandoned St. Louis, Peoria and North Western Railway railroad line as a trail that will extend from Girard, Illinois, to Athens, Illinois.

Notable people edit

Sister cities edit

Springfield, Illinois has two sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

It maintains a "Friendship" city designation with Killarney, Ireland.[125]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Official website

- ^ a b Keck, Patrick (February 20, 2023). "Election 2023: Portions of two townships could be annexed into Springfield". State Journal-Register. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Springfield, Illinois

- ^ a b Springfield Online Archived 2007-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on April 13, 2007

- ^ "Name of Local Government: Springfield". Illinois State Archives. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Look Up a ZIP Code". USPS.com. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ "Look Up a ZIP Code". USPS.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Springfield (city), Illinois". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. July 8, 2014. Archived from the original on July 3, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ "Estimates of Resident Population Change and Rankings: July 1, 2012 to July 1, 2013". U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2014. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Springfield history Archived 2007-01-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on February 21, 2007

- ^ a b c Springfield, Illinois, archived from the original on April 1, 2012, retrieved March 7, 2017

- ^ a b c d A Brief Sketch of Springfield, Illinois, archived from the original on March 5, 2012, retrieved March 7, 2017

- ^ John C. Powers, Jr. History of the Early Settlers of Springfield, Illinois, 1876, reprinted 1998, ISBN 9780788410185

- ^ a b c d "Springfield, Illinois". American History. 32 (4): 60. September–October 1997. ISSN 1076-8866.[permanent dead link], Academic Search Premier, (EBSCO). [dead link]

- ^ Winkle, (1998)

- ^ a b c d Kenneth J. Winkle, "The Voters of Lincoln's Springfield: Migration and Political Participation in an Antebellum City." Journal of Social History 1992 25(3): 595–611. ISSN 0022-4529 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ^ Robert E., Coleberd, Jr. "John Williams: a Merchant Banker in Springfield, Illinois." Agricultural History 1968 42(3): 259–265. ISSN 0002-1482

- ^ Roger Howard Dallmann, "Springfield Seminary." Concordia Historical Institute Quarterly 1977 50(3): 106–130. ISSN 0010-5260

- ^ Camilla A. Quinn, "Soldiers on Our Streets: the Effects of a Civil War Military Camp on the Springfield Community", Illinois Historical Journal 1993 86(4): 245–256. ISSN 0748-8149

- ^ Ron Sakolsky, "Utopia at Your Doorstep: Vachel Lindsay's Golden Book of Springfield." Utopian Studies 2001 12(2): 53–64. ISSN 1045-991X Fulltext: Ebsco

- ^ a b Donald P. Hallmark, "Frank Lloyd Wright's Dana–Thomas House: Its History, Acquisition, and Preservation", Illinois Historical Journal 1989 82(2): 113–126. ISSN 0748-8149

- ^ "Welcome to the Dana–Thomas House". Dana-thomas.org. August 23, 1983. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ Alexander O. Boulton, "Pride of the Prairie", American Heritage 1991 42(4): 62–69. ISSN 0002-8738 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ^ Chicago Commission on Race Relations (1919); Crouthamel (1960); Senechal (1990)

- ^ a b c d e f "Springfield Tornadoes of March 12, 2006". National Weather Service Lincoln, Illinois. May 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved September 17, 2014.

- ^ Pearson, Rick; Long, Ray (February 10, 2007). "Obama: I'm running for president". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Willman, H.B., and J.C. Frye, 1970, Pleistocene Stratigraphy of Illinois. Bulletin no. 94, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, Illinois.

- ^ McKay, E.D., 2007, Six Rivers, Five Glaciers, and an Outburst Flood: the Considerable Legacy of the Illinois River. Proceedings of the 2007 Governor's Conference on the Management of the Illinois River System: Our continuing Commitment, 11th Biennial Conference, Oct. 2–4, 2007, 11 p.

- ^ Warner, Kelly L. "Lower Illinois River Basin – Physiography – Water-Quality Assessment of the Lower Illinois River Basin: Environmental Setting, USGS Water Resources of Illinois". United States Geological Survey. Il.water.usgs.gov/. p. 3. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Lake Springfield Archived 2000-08-24 at the Wayback Machine, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ About CWLP Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Lake Water Levels Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, City Water, Light & Power, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Normal Monthly Precipitation, Inches Archived 2006-09-01 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Normal Daily Temperature, °F Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Meteorology, University of Utah. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ a b New City Tornado Sirens are Fully Operational Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Springfield and Quincy Fire Department Awarded $146,646 in Homeland Security Grants Archived 2007-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release, Office of Congressman Ray Lahood, February 23, 2005. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Minutes of the Springfield City Council – April 4, 2006 Archived September 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, (PDF), City of Springfield, City Clerk. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for Springfield/Capital ARPT, IL 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ "The Grand Avenues". October 26, 2013.

- ^ Neighborhood Associations Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, Office of Planning & Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ "Boundaries Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine", Lincoln Park Neighborhood Association. Retrieved May 20, 2007.

- ^ Gray, Don (September 16, 2022). City of Springfield Ward Map (PDF) (Map). Sangamon County. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Springfield city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Springfield city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Springfield city, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Illinois – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Major Springfield Employers Archived 2007-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, Office of Planning and Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Springfield, IL Economy at a Glance". Bls.gov. February 28, 2014. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ a b "Living Wage Calculation for Springfield city, Sangamon County, Illinois". Living Wage Project. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- ^ "City of Springfield CAFR 2021" (PDF). Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Thomas J. and Kirsch, Sarah. "Rhymes to Be Traded for Bread" Archived 2007-02-05 at the Wayback Machine, Web Exhibit, University of Illinois Springfield. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ John L. Lewis House Archived 2006-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Historic Sites Commission of Springfield, Illinois. Retrieved February 21, 2007

- ^ Hales, Linda. Getting One's Fill at Hillwood Archived 2018-08-24 at the Wayback Machine, Editorial Review, Washington Post, September 24, 2000. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Murdin, Paul, ed. (2000). "Nicholson, Seth Barnes (1891-1963)". Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. p. 3892. Bibcode:2000eaa..bookE3892.. ISBN 978-0333750889.

- ^ a b "Protestant Exiles from Madeira in Illinois". Library of Congress. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Martin, Andrea. "Carpenter Street Underpass" (PDF). Springfield Railroads Improvement Project. US Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration and the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Illinois Authors on the Illinois State Library http://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/library/about/illinois_authors.html Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 8/30/13

- ^ Artie Matthews, Biography, AllMusic. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Morris Day and The Time Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, Richard De La Fonte Agency, Inc. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ "The Black Sheep Cafe". Black Sheep. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ "The Springfield Old Capitol Art Fair :: Springfield Illinois". www.socaf.org. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ staff. "Annual Route 66 Film Festival". Central Illinois Film Commission. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- ^ The Independent: A Magazine for Video and Filmmakers. Vol. 28. Foundation for Independent Video and Film. 2005. pp. 56–58.

- ^ "Interview with Edwin Waldmire – Illinois Regional Archives Depository (IRAD)" (PDF). Oral History Collections. Brookens Library, University of Illinois Springfield. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Storch, Charles. Birthplace (maybe) of the corn dog, Chicago Tribune, August 16, 2006, Newspaper Source, (EBSCO). Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Harris, Patricia; Lyon, David (November 20, 2006). "The hottest thing in sandwiches". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on December 2, 2006. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ "117-Year-Old Brewing Co. Closes" (PDF). Chicago Tribune. August 8, 1966. p. C6. Retrieved March 10, 2007 – via ProQuest.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Pearson, Rick. "A Guide for the National Press", Chicago Tribune, February 9, 2007. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ a b Zimmerman-Wills, Penny. "Capital City Chilli" Archived 2007-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, Illinois Times, January 30, 2003, Retrieved February 23, 2007

- ^ a b About the City Archived 2007-03-15 at the Wayback Machine, Springfield, Illinois Convention and Visitors Bureau. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ Thomas, Benjamin P. Abraham Lincoln: A Biography Archived 2012-05-29 at the Wayback Machine, Alfred Knopf: New York, (1952). Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ The visit of The Emir of Qatar to the United States (May 2005) Archived 2007-05-02 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release, Embassy of the State of Qatar in Washington, D.C.. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Museum Dedication – A Look Back Archived 2009-02-15 at the Wayback Machine, (note:automatically plays band music), Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Reardon Patrick T. Donner Party began here too, Chicago Tribune, February 7, 2007. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ a b Dana–Thomas House Archived 2007-08-25 at the Wayback Machine, State Historic Sites, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ The 46th Annual Carillon Festival Archived 2007-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release, Thomas Rees Memorial Carillon. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Jeff Fassero Archived 2006-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, Player Pages, Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Kevin Seitzer Archived 2005-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, Player Pages, Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Ryan O'Malley Archived 2007-02-12 at the Wayback Machine, Player Pages, Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Robin Roberts Archived 2007-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, Player Pages, Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Lew Freedman. Gamble Paying Off, Chicago Tribune, February 10, 2007.

- ^ Andre Iguodala to Donate $19,000 to Assist Tornado Relief Efforts in Springfield, Ill. Archived 2006-04-21 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release, Philadelphia 76ers, April 4, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2007

- ^ "Ryan Held Bio – SwimSwam". Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ a b Code of Ordinances Archived 2006-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, City of Springfield, Title III: Chapter 32: Article I – Executive Branch. Municode.com. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ a b c Code of Ordinances Archived 2006-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, City of Springfield, Title I: Chapter 30: General Provisions. Municode.com. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Code of Ordinances Archived 2006-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, City of Springfield, Title III: Chapter 31: Legislative. Municode.com. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ Olsen, Dean. "Candidates file for municipal elections". Illinois Times. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "Our Candidates". Sangamon County Democratic Party. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ "CITY OF SPRINGFIELD". My Site. Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ^ Article IV – Section 4, Jurisdiction Archived 2007-02-23 at the Wayback Machine, The Judiciary, Constitution of the State of Illinois, Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Article IV – Section 1, Legislature – Power and Structure Archived 2012-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, The Legislature, Constitution of the State of Illinois, Illinois General Assembly. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ a b c Gauen, Pat. "Illinois corruption explained: the capital is too far from Chicago " (Archive). St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved on May 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Reeder, Scott. "What does it cost taxpayers to pay for lawmakers' empty Springfield residences?" (Archive). Illinois News Network. September 11, 2014. Retrieved on May 26, 2016.

- ^ Capital Township Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, Official site. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- ^ Sangamon County Fact Sheet Archived 2007-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, Illinois State Archives. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ Spearie, Steven (November 1, 2019). "Former city officer gets 24 months probation". The State Journal-Register. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Schools Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, Springfield Public School District 186. Retrieved February 24, 2007

- ^ Sacred Heart-Griffin. "Sacred Heart – Griffin High School". Shg.org. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ Lutheran High Archived 2007-03-08 at the Wayback Machine, Main page. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Office of Student Affairs Archived 2007-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ New SimmonsCooper Cancer Institute Building Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, SimmonsCooper Cancer Institute, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. Retrieved February 24, 2007.

- ^ Landis, Tim (June 2, 2010). "Lafferty named publisher of The State Journal-Register". The State Journal-Register. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved November 23, 2018.

- ^ "Champaign – Springfield – Decatur Television Stations – Station Index". www.stationindex.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ The Rise & Fall of WJJY-TV Archived 2007-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on March 8, 2007.

- ^ Illinois Radio Stations Archived 2007-08-14 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on August 23, 2007.

- ^ Springfield Illinois news media. Retrieved on March 8, 2007.

- ^ "Doctors Hospital's Medical Equipment Sold at Auction – Health News". redOrbit. January 23, 2006. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "State board OKs Vibra's purchase of Kindred Hospital". The State Journal-Register. Springfield, Illinois. August 15, 2013. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "Vibra Hospital closure came amid declining revenues; fate of property uncertain".

- ^ Overview Archived 2001-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, Prairie Heart Institute, St. John's Hospital. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Springfield profile Archived 2007-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, Office of Planning & Economic Development, City of Springfield. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ^ "Amtrak Lincoln Service and Missouri River Runner Timetable" (PDF). Amtrak. September 13, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- ^ "Sangamon Mass Transit District". Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln Capital Airport (SPI) – Springfield, IL". Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ "Springfield Park District – Bunn to Lost Bridge Trail". www.springfieldparks.org. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Chris Young (July 27, 2010). "Sangamon Valley Trail officially opens". State Journal-Register. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ a b "Springfield International Relationships". Official Springfield Website. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ "Springfield, Illinois". legacy.sistercities.org. Retrieved August 24, 2018.[permanent dead link]

References edit

- Chicago Commission on Race Relations (1922). "The Springfield Riot". The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press. pp. 66–71.

- History of Sangamon County, Illinois: Together with Sketches of Its Cities, Villages and Townships ... Portraits of Prominent Persons, and Biographies of Representative Citizens. History of Illinois. Chicago: Inter-state Pub. Co. 1881.

Further reading edit

- Angle, Paul M. "Here I have lived": A history of Lincoln's Springfield, 1821–1865 (1935, 1971)

- Crouthamel, James L. "The Springfield Race Riot of 1908." Journal of Negro History 1960 45(3): 164–181. ISSN 0022-2992 in Jstor

- Harrison, Shelby Millard, ed. The Springfield Survey: Study of Social Conditions in an American City (1920), famous sociological study of the city vol 3 online

- "Springfield". Illinois State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1858 and 1859. Chicago, Ill: George W. Hawes. 1858. OCLC 4757260. OL 24140361M.

- Laine, Christian K. Landmark Springfield: Architecture and Urbanism in the Capital City of Illinois. Chicago: Metropolitan, 1985. 111 pp. ISBN 0935119019 OCLC 12942732

- Lindsay, Vachel. The Golden Book of Springfield (1920), a novel excerpt and text search

- Senechal, Roberta. The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot: Springfield, Illinois, in 1908. 1990. 231 pp.

- VanMeter, Andy. "Always My Friend: A History of the State Journal-Register and Springfield." Springfield, Ill.: Copley, 1981. 360 pp. history of the daily newspapers

- Wallace, Christopher Elliott. "The Opportunity to Grow: Springfield, Illinois during the 1850s." PhD dissertation Purdue U. 1983. 247 pp. DAI 1984 44(9): 2864-A. DA8400427 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Winkle, Kenneth J. "The Second Party System in Lincoln's Springfield." Civil War History 1998 44(4): 267–284. ISSN 0009-8078

External links edit

- Official website

- Springfield, Illinois at Curlie

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 739.