Samuel (also Samoil[2] or Samuil; Bulgarian: Самуил, pronounced [sɐmuˈiɫ]; Macedonian: Самоил/Самуил,[3][4] pronounced [samɔˈiɫ/sɐmuˈiɫ]; Old Church Slavonic: Самоилъ; died 6 October 1014) was the Tsar (Emperor) of the First Bulgarian Empire from 997 to 6 October 1014.[5] From 977 to 997, he was a general under Roman I of Bulgaria,[6] the second surviving son of Emperor Peter I of Bulgaria, and co-ruled with him, as Roman bestowed upon him the command of the army and the effective royal authority.[7] As Samuel struggled to preserve his country's independence from the Byzantine Empire, his rule was characterized by constant warfare against the Byzantines and their equally ambitious ruler Basil II.

| Samuel | |

|---|---|

| Tsar of Bulgaria | |

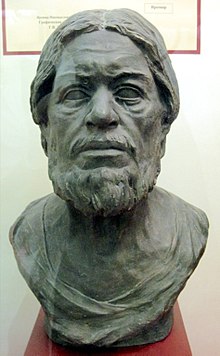

Facial reconstruction based on his remains | |

| Reign | 997 – 6 October 1014 |

| Predecessor | Roman |

| Successor | Gavril Radomir |

| Died | 6 October 1014 Prespa,[1] First Bulgarian Empire |

| Spouses | Agatha |

| Issue | Gavril Radomir Miroslava |

| Dynasty | Cometopuli |

| Father | Nicholas |

| Mother | Ripsimia of Armenia |

| Religion | Bulgarian Orthodox |

In his early years, Samuel managed to inflict several major defeats on the Byzantines and to launch offensive campaigns into their territory.[8] In the late 10th century, the Bulgarian armies conquered the Serb principality of Duklja[9] and led campaigns against the Kingdoms of Croatia and Hungary. But from 1001, he was forced mainly to defend the Empire against the superior Byzantine armies. Samuel died of a heart attack on 6 October 1014, two months after the catastrophic battle of Kleidion. His successors failed to organize a resistance, and in 1018, four years after Samuel's death, the country capitulated, ending the five decades-long Byzantine–Bulgarian conflict.[10]

Samuel was considered "invincible in power and unsurpassable in strength".[11][12] Similar comments were made even in Constantinople, where John Kyriotes penned a poem offering a punning comparison between the Bulgarian Emperor and Halley's comet, which appeared in 989.[13][14] During Samuel's reign, Bulgaria gained control of most of the Balkans (with the notable exception of Thrace) as far as southern Greece. He moved the capital from Skopje to Ohrid,[8][15] which had been the cultural and military centre of southwestern Bulgaria since Boris I's rule,[16] and made the city the seat of the Bulgarian Patriarchate. Because of this, his realm is sometimes called the Western Bulgarian Empire.[17][18] Samuel's energetic reign restored Bulgarian might on the Balkans, even though the Empire was disestablished after his death.

The rise of the Cometopuli

editThe Cometopuli

editSamuel was the fourth[19] and youngest son of count Nicholas, a Bulgarian noble, who might have been the count of Sredets district (modern-day Sofia),[20] although other sources suggest that he was a regional count of Prespa district in the region of Macedonia.[21] His mother was Rhipsime of Armenia.[22] The actual name of the dynasty is not known. Cometopuli is the nickname used by Byzantine historians which is translated as "sons of the count". The Cometopuli rose to power out of the disorder that occurred in the Bulgarian Empire from 966 to 971.

Rus' invasion and the deposition of Boris II

editDuring the reign of Emperor Peter I, Bulgaria prospered in a long-lasting peace with Byzantium. This was secured by the marriage of Peter with the Byzantine princess Maria Lakapina, granddaughter of Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos. However, after Maria's death in 963, the truce had been shaken and it was at this time or later that Peter I sent his sons Boris and Roman to Constantinople as honorary hostages, to honor the new terms of the peace treaty.[23] During these years the Byzantines and Bulgarians had entangled themselves in a war with Kievan Rus' Prince Sviatoslav, who invaded Bulgaria several times. After a defeat from Sviatoslav, Peter I suffered a stroke and abdicated his throne in 969 (he died the next year). Boris was allowed back to Bulgaria to take his father's throne, restore order and oppose Sviatoslav, but had little success. This was allegedly used by Nicholas and his sons, who were contemplating a revolt in 969.[24]

The Rus' invaded Byzantine Thrace in 970, but suffered a defeat in the Battle of Arcadiopolis. The new Byzantine Emperor John Tzimiskes used this to his advantage. He quickly invaded Bulgaria the following year, defeated the Rus, and conquered the Bulgarian capital Preslav. Boris II of Bulgaria was ritually divested of his imperial insignia in a public ceremony in Constantinople and he and his brother Roman of Bulgaria remained in captivity. Although the ceremony in 971 had been intended as a symbolic termination of the Bulgarian Empire, the Byzantines were unable to assert their control over the western provinces of Bulgaria. Count Nicholas, Samuel's father, who had close ties to the royal court in Preslav,[25] died in 970. In the same year[26] "the sons of the count" (the Cometopuli) David, Moses, Aaron and Samuel rebelled.[27] The series of events are not clear due to contradicting sources, but it is sure that after 971 Samuel and his brothers were the de facto rulers of the western Bulgarian lands.

In 973, the Cometopuli (described by Thietmar of Merseburg simply as the Bulgarians)[28] sent envoys to the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I in Quedlinburg in an attempt to secure the protection of their lands.[29] The brothers ruled together in a tetrarchy.[30] David ruled the southernmost regions and led the defense of one of the most dangerous border areas, around Thessaloniki and Thessaly.[30] The centres of his possessions were Prespa and Kastoria. Moses ruled from Strumitsa,[30] which would be an outpost for attacks on the Aegean coast and Serres. Aaron ruled from Sredets,[30] and was to defend the main road from Adrianople to Belgrade, and to attack Thrace. Samuel ruled northwestern Bulgaria from the strong fortress of Vidin. He was also to organize the liberation of the conquered areas to the east, including the old capital Preslav.[31] Some records suggest that David played a major role in this tumultuous period of Bulgarian history.[32]

War with Byzantium

editAfter John I Tzimiskes died on 11 January 976, the Cometopuli launched an assault along the whole border. Within a few weeks, however, David was killed by Vlach vagrants and Moses was fatally injured by a stone during the siege of Serres.[33] The brothers' actions to the south detained many Byzantine troops and eased Samuel's liberation of northeastern Bulgaria. A local Bulgarian uprising broke there,[34] led by two boyars – Petar and Boyan, who became allies of the Cometopuli and submitted to their rule.[35] The Byzantine army was defeated and retreated to Crimea.[36][37] Any Bulgarian nobles and officials who had not opposed the Byzantine conquest of the region were executed, and the war continued north of the Danube until the enemy was scattered and Bulgarian rule was restored.[38]

After suffering these defeats in the Balkans, the Byzantine Empire descended into civil war. The commander of the Asian army, Bardas Scleros, rebelled in Asia Minor and sent troops under his son Romanus in Thrace to besiege Constantinople. The new Emperor Basil II did not have enough manpower to fight both the Bulgarians and the rebels and resorted to treason, conspiracy and complicated diplomatic plots.[39] Basil II made many promises to the Bulgarians and Scleros to divert them from allying against him.[40] Aaron, the eldest living Cometopulus, was tempted by an alliance with the Byzantines and the opportunity to seize power in Bulgaria for himself. He held land in Thrace, a region potentially subject to the Byzantine threat. Basil reached an agreement with Aaron, who asked to marry Basil's sister to seal it. Basil instead sent the wife of one of his officials with the bishop of Sebaste. However, the deceit was uncovered and the bishop was killed.[41] Nonetheless, negotiations proceeded and concluded in a peace agreement. The historian Scylitzes wrote that Aaron wanted sole power and "sympathized with the Romans".[42] Samuel learned of the conspiracy and the clash between the two brothers was inevitable. The quarrel broke out in the vicinity of Dupnitsa on 14 June 976 and ended with the annihilation of Aaron's family. Only his son, Ivan Vladislav, survived because Samuel's son Gavril Radomir pleaded on his behalf.[43] From that moment on, practically all power and authority in the state were held by Samuel and the danger of an internal conflict was eliminated.

However, another theory suggests that Aaron participated in the battle of the Gates of Trajan which took place ten years later. According to that theory Aaron was killed on 14 June 987 or 988.[44][45]

Co-rule with Roman

editAfter the Byzantine plan to use Aaron to cause instability in Bulgaria failed, they tried to encourage the rightful heirs to the throne,[46] Boris II and Roman, to oppose Samuel. Basil II hoped that they would win the support of the nobles and isolate Samuel or perhaps even start a Bulgarian civil war.[47] Boris and Roman were sent back in 977[48] but while they were passing through a forest near the border, Boris was killed by Bulgarian guards who were misled by his Byzantine clothing. Roman, who was walking some distance behind, managed to identify himself to the guards.[49]

Roman was taken to Vidin, where he was proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria.[50] Samuel became his first lieutenant and general and together they gathered an army and fought the Byzantines.[51] During his captivity, Roman had been castrated on the orders of John I Tzimiskes so that he would not have heirs. Thus Samuel was certain to eventually succeed Roman. The new emperor entrusted Samuel with the state administration and became occupied with church and religious affairs.[52]

As the main effort of Basil II was concentrated against the rebel Skleros, Samuel's armies attacked the European possessions of the Byzantine Empire. Samuel invaded not only Thrace and the area of Thessaloniki, but also Thessaly, Hellas and the Peloponnese. Many Byzantine fortresses fell to the Bulgarians.[53] Samuel wanted to seize the important fortress of Larissa, which controlled the key routes in Thessaly, and from 977 to 983 the town was blockaded. After starvation forced the Byzantines to surrender,[15] the population was deported to the interior of Bulgaria and the males were forced to enlist in the Bulgarian army.[54] Although Basil II sent forces to the region, they were defeated. With this victory, Bulgaria had gained influence over most of the southwestern Balkans, although it did not occupy some of these territories. From Larissa, Samuel took the relics of Saint Achilleios, which were laid in a specially built church of the same name on an island in Lake Prespa.[55][56][57]

The Bulgarian successes in the west raised fears in Constantinople, and after serious preparations, Basil II launched a campaign into the very centre of the Bulgarian Empire[58] to distract Samuel from southern Greece.[59][60] The Byzantine army passed through the mountains around Ihtiman and besieged Sredets in 986. The Byzantines assaulted the city for 20 days, but their attacks proved fruitless and costly: the Bulgarians came out of the city several times, killed many enemy soldiers and captured draught animals and horses. Eventually, the Bulgarian troops burned the siege equipment of the Byzantine army, forcing Basil II to withdraw to Thrace, but on 17 August 986,[61] while passing through the mountains, the Byzantine army was ambushed and routed at the Trajan's Gates Pass. This was a significant blow for Basil,[62][63] who was one of the few to return to Constantinople; his personal treasure was captured by the victors.[64][65]

"Even if the sun would have come down, I would have never thought that the Moesian [Bulgarian] arrows were stronger than the Avzonian [Roman, Byzantine] spears.

... And when you, Phaethon [Sun], descend to the earth with your gold-shining chariot, tell the great soul of the Caesar: The Danube [Bulgaria] took the crown of Rome. The arrows of the Moesians broke the spears of the Avzonians."

John Kyriotes Geometres on the battle of the Gates of Trajan.[66]

After the defeat, the rebellion of Bardas Phocas diverted the efforts of the Byzantine Empire into another civil war.[67][68][69] Samuel seized the opportunity and began to exert pressure on Thessaloniki.[70][71] Basil II sent a large army to the town and appointed a new governor, Gregorios Taronites,[72] but he was powerless to stop the Bulgarian advance. By 989, the Bulgarian troops had penetrated deep into Byzantine territory,[73] and seized many fortresses, including such important cities as Veria and Servia. In the south, the Bulgarians marched throughout Epirus and in the west they seized the area of modern Durrës (medieval Dyrrhachium or Drach) on the Adriatic Sea.[74][75][76]

In 989, Phocas was killed and his followers surrendered, and the following year Basil II reached an agreement with Skleros.[77] The Byzantines focused their attention on Bulgaria,[78] and counter-attacked in 991.[79][80] The Bulgarian army was defeated and Roman was captured while Samuel managed to escape.[81] The Byzantines conquered some areas; in 995, however, the Arabs invaded Asia Minor and Basil II was forced to move many of his troops to combat this new threat. Samuel quickly regained the lost lands and advanced south. In 996, he defeated the Byzantines in the battle of Thessaloniki. During the battle, Thessaloniki's governor, Gregorios, perished and his son Ashot was captured.[82] Elated by this success, the Bulgarians continued south. They marched through Thessaly, overcame the defensive wall at Thermopylae and entered the Peloponnese, devastating everything on their way.[83]

As a response, a Byzantine army under Nikephorus Uranos was sent after the Bulgarians, who returned north to meet it. The two armies met near the flooded river of Spercheios. The Byzantines found a place to ford, and on the night of 19 July 996 they surprised the unprepared Bulgarian army and routed it in the battle of Spercheios.[84] Samuel's arm was wounded and he barely escaped captivity; he and his son allegedly feigned death.[85] After nightfall they headed for Bulgaria and walked 400 kilometres (249 mi) home. Research of Samuel's grave suggests that the bone in his arm healed at an angle of 140° but remained crippled.[86]

Emperor

editIn 997, Roman died in captivity in Constantinople, ending the line of rulers started by Krum. Because of the war with Byzantium, it was dangerous to leave the throne vacant for long, and Samuel was chosen as the new Emperor of Bulgaria because he had the closest relations to the deceased emperor and was Roman's long-standing military commander.[87] The presbyter of Duklja also marked the event: "By that time among the Bulgarian people rose one Samuel, who proclaimed himself emperor. He led a long war against the Byzantines and expelled them from the whole territory of Bulgaria, so that the Byzantines did not dare to approach it".[88]

"Above the comet scorched the sky, below the Cometopoulos (Samuel) burns the West."

John Kyriotes Geometres[13]

Constantinople would not recognize the new emperor, as for the Byzantines Boris II's abdication symbolized the official end of Bulgaria and Samuel was considered a mere rebel. Instead Samuel sought recognition from the Pope, which would be a serious blow to the position of the Byzantines in the Balkans and would weaken the influence of the Patriarch of Constantinople, thereby benefiting both the See of Rome and Bulgaria. Samuel possibly received his imperial crown from Pope Gregory V.[89]

War against Serbs and Croats

editIn 998, Samuel launched a major campaign against the Duklja to prevent an alliance between Prince Jovan Vladimir and the Byzantines. When the Bulgarian troops reached Duklja, the Serbian prince and his people withdrew to the mountains. Samuel left part of the army at the foot of the mountains and led the remaining soldiers to besiege the coastal fortress of Ulcinj. In an effort to prevent bloodshed, he asked Jovan Vladimir to surrender. After the prince refused, some Serb nobles offered their services to the Bulgarians and, when it became clear that further resistance was fruitless, the Serbs surrendered. Jovan Vladimir was exiled to Samuel's palaces in Prespa.[90]

The Bulgarian troops proceeded to pass through Dalmatia, taking control of Kotor and journeying to Dubrovnik. Although they failed to take Dubrovnik, they devastated the surrounding villages. The Bulgarian army then attacked Croatia in support of the rebel princes Krešimir III and Gojslav and advanced northwest as far as Split, Trogir and Zadar, then northeast through Bosnia and Raška and returned to Bulgaria.[90] This Croato-Bulgarian War allowed Samuel to install vassal monarchs in Croatia.[citation needed]

Samuel's relative Theodora Kosara fell in love with the captive Jovan Vladimir. The couple married after gaining Samuel's approval, and Jovan returned to his lands as a Bulgarian official along with his uncle Dragomir, whom Samuel trusted.[91] Meanwhile, Princess Miroslava fell in love with the Byzantine noble captive Ashot, son of Gregorios Taronites, the dead governor of Thessaloniki, and threatened to commit suicide if she was not allowed to marry him. Samuel conceded and appointed Ashot governor of Dyrrhachium.[92] Samuel also sealed an alliance with the Magyars when his eldest son and heir, Gavril Radomir, married the daughter of the Hungarian Grand Prince Géza.[93]

Advance of the Byzantines

editThe beginning of the new millennium saw a turn in the course of Byzantine-Bulgarian warfare.[94] Basil II had amassed an army larger and stronger than that of the Bulgarians: determined to definitively conquer Bulgaria, he moved much of the battle-seasoned military forces from the eastern campaigns against the Arabs to the Balkans[95][96] and Samuel was forced to defend rather than attack.[97]

In 1001, Basil II sent a large army under the patrician Theodorokanos and Nikephoros Xiphias to the north of the Balkan Mountains to seize the main Bulgarian fortresses in the area. The Byzantine troops recaptured Preslav and Pliska,[98] putting north-eastern Bulgaria once again under Byzantine rule. The following year, they struck in the opposite direction, marching through Thessaloniki to tear off Thessaly and the southernmost parts of the Bulgarian Empire. Although the Bulgarian commander of the fortress of Veroia, Dobromir, was married to one of Samuel's nieces, he voluntarily surrendered the fort and joined the Byzantines.[99] The Byzantines also captured the fortress of Kolidron without a fight, but its commander Dimitar Tihon managed to retreat with his soldiers and join Samuel.[100] The next town, Servia, did not fall so easily; its governor Nikulitsa organized the defenders well. They fought until the Byzantines penetrated the walls and forced them to surrender.[101] Nikulitsa was taken to Constantinople and given the high court title of patrician, but he soon escaped and rejoined the Bulgarians. He attempted to retake Servia, but the siege was unsuccessful and he was captured again and imprisoned.[102]

Meanwhile, Basil II's campaign reconquered many towns in Thessaly. He forced the Bulgarian population of the conquered areas to resettle in the Voleron area between the Mesta and Maritsa rivers. Edessa resisted for weeks but was conquered following a long siege. The population was moved to Voleron and its governor Dragshan was taken to Thessaloniki, where he was betrothed to the daughter of a local noble. Unwilling to be married to an enemy, Dragshan three times tried to flee to Bulgaria and was eventually executed.[103]

War with Hungary

editThe Byzantine–Bulgarian conflict reached its apex in 1003, when Hungary became involved. Since the beginning of the 9th century, the Bulgarian territory had stretched beyond the Carpathian Mountains as far as the Tisza River and the middle Danube. During the reign of Samuel, the governor of these northwestern parts was duke Ahtum, the grandson of duke Glad, who had been defeated by the Hungarians in the 930s. Ahtum commanded a strong army and firmly defended the northwestern borders of the Empire. He also built many churches and monasteries through which he spread Christianity in Transylvania.[104][105]

Although Gavril Radomir's marriage to the daughter of the Hungarian ruler had established friendly relations between the two strongest states of the Danube area, the relationship deteriorated after Géza's death. The Bulgarians supported Gyula and Koppány as rulers instead of Géza's son Stephen I. As a result of this conflict, the marriage between Gavril Radomir and the Hungarian princess was dissolved. The Hungarians then attacked Ahtum, who had directly backed the pretenders for the Hungarian crown. Stephen I convinced Hanadin, Ahtum's right-hand man, to help in the attack. When the conspiracy was uncovered Hanadin fled and joined the Hungarian forces.[106] At the same time, a strong Byzantine army besieged Vidin, Ahtum's seat. Although many soldiers were required to participate in the defense of the town, Ahtum was occupied with the war to the north. After several months he died in battle when his troops were defeated by the Hungarians.[107] As a result of the war, Bulgarian influence to the northwest of the Danube diminished.

Further Byzantine successes

editThe Byzantines took advantage of the Bulgarian troubles in the north. In 1003, Basil II led a large army to Vidin, northwestern Bulgaria's most important town. After an eight-month siege, the Byzantines ultimately captured the fortress,[108] allegedly due to betrayal by the local bishop.[109] The commanders of the town had repulsed all previous attempts to break their defence, including the use of Greek fire.[100] While Basil's forces were engaged there, Samuel struck in the opposite direction: on 15 August he attacked Adrianople and plundered the area.[110]

Basil II decided to return to Constantinople afterwards, but, fearing an encounter with the Bulgarian army on the main road to his capital, he used an alternate route.[citation needed] The Byzantines marched south through the Morava valley and reached a key Bulgarian city, Skopje, in 1004. The Bulgarian army was camping on the opposite side of the Vardar River. After finding a ford and crossing the river, Basil II attacked and defeated Samuel's unsuspecting army, using the same tactics employed at Spercheios.[111] The Byzantines continued east and besieged the fortress of Pernik. Its governor, Krakra, was not seduced by Basil's promises of a noble title and wealth, and successfully defended the fortress. The Byzantines withdrew to Thrace after suffering heavy losses.[108][112]

In the same year, Samuel undertook a march against Thessaloniki. His men ambushed and captured its governor, Ioannes Chaldus,[100][113] but this success could not compensate for the losses the Bulgarians had suffered in the past four years. The setbacks in the war demoralized some of Samuel's military commanders, especially the captured Byzantine nobles. Samuel's son-in-law Ashot, the governor of Dyrrhachium, made contact with the local Byzantines and the influential John Chryselios, Samuel's father-in-law. Ashot and his wife boarded one of the Byzantine ships that were beleaguering the town and fled to Constantinople. Meanwhile, Chryselios surrendered the city to the Byzantine commander Eustathios Daphnomeles in 1005, securing the title of patrician for his sons.[92][114]

In 1006–1007, Basil II penetrated deep into the Bulgarian-ruled lands[115] and in 1009 Samuel's forces were defeated at Kreta, east of Thessaloniki.[116] During the next years, Basil launched annual campaigns into Bulgarian territory, devastating everything on his way.[117] Although there was still no decisive battle, it was clear that the end of the Bulgarian resistance was drawing nearer; the evidence was the fierceness of the military engagements and the constant campaigns of both sides which devastated the Bulgarian and Byzantine realms.[116][118][clarification needed]

Disaster at Kleidion

editIn 1014, Samuel resolved to stop Basil before he could invade Bulgarian territory. Since the Byzantines usually used the valley of the Strumitsa River for their invasions into Bulgaria, Samuel built a thick wooden wall in the gorges around the village of Klyuch (also Kleidion, "key") to bar the enemy's way.

When Basil II launched his next campaign in the summer of 1014, his army suffered heavy casualties during the assaults on the wall. Meanwhile, Samuel sent forces under his general Nestoritsa to attack Thessaloniki so as to distract Basil's forces away from this campaign. Nestoritsa was defeated near the city[119] by its governor Botaniates, who later joined the main Byzantine army near Klyuch.[120] After several days of continuous attempts to break through the wall, one Byzantine commander, the governor of Plovdiv Nicephorus Xiphias, found a by-pass and, on 29 July, attacked the Bulgarians from the rear.[117] Despite the desperate resistance the Byzantines overwhelmed the Bulgarian army and captured around 14,000 soldiers,[121] according to some sources even 15,000.[122] Basil II immediately sent forces under his favourite commander Theophylactus Botaniates to pursue the surviving Bulgarians, but the Byzantines were defeated in an ambush by Gavril Radomir, who personally killed Botaniates. After the Battle of Kleidion, on the order of Basil II the captured Bulgarian soldiers were blinded; one of every 100 men was left one-eyed so as to lead the rest home.[123][124] The blinded soldiers were sent back to Samuel who reportedly had a heart attack upon seeing them. He died two days later, on 6 October 1014.[117] This savagery gave the Byzantine Emperor his byname Boulgaroktonos ("Bulgar-slayer" in Greek: Βουλγαροκτόνος). Some historians theorize it was the death of his favourite commander that infuriated Basil II to blind the captured soldiers.[125]

The battle of Kleidion had major political consequences. Although Samuel's son and successor, Gavril Radomir, was a talented military leader, he was murdered by his cousin Ivan Vladislav, who, ironically, owed his life to him. Unable to restore the Bulgarian Empire's previous power, Ivan Vladislav himself was killed while attacking Dyrrhachium. After that, the widowed empress Maria and many Bulgarian governors, including Krakra, surrendered to the Byzantines. Presian, Ivan Vladislav's eldest son, fled with two of his brothers to Mount Tomorr, before they too surrendered. Thus the First Bulgarian Empire came to an end in 1018, only four years after Samuel's death.[126] Most of its territory was incorporated within the new Theme of Bulgaria, with Skopje as its capital.[127]

In the extreme northwest, the duke of Syrmia, Sermon, was the last remnant of the once mighty Empire. He was deceived and killed by the Byzantines in 1019.[128]

Family, grave and legacy

editSamuel's wife was called Agatha, and was the daughter of the magnate of Dyrrhachium John Chryselios.[129] Only two of Samuel's and Agatha's children are definitely known by name: Samuel's heir Gavril Radomir and Miroslava. Two further, unnamed daughters, are mentioned after the Bulgarian surrender in 1018, while Samuel is also recorded as having had a bastard son.[129] Another woman, Theodora Kosara, who was wedded to Jovan Vladimir of Duklja and was considered by earlier scholarship as Samuel's daughter, is now regarded to have been simply a relative, perhaps a niece of Agatha.[130] Gavril Radomir married twice, to Ilona of Hungary and Irene from Larissa. Miroslava married the captured Byzantine noble Ashot Taronites.

After the fall of Bulgaria, Samuel's descendants assumed important positions in the Byzantine court after they were resettled and given lands in Asia Minor and Armenia. One of his granddaughters, Catherine, became empress of Byzantium. Another (supposed) grandchild, Peter II Delyan, led an attempt to restore the Bulgarian Empire after a major uprising in 1040 – 1041. Two other women of the dynasty became Byzantine empresses,[131] while many nobles served in the army as strategos or became governors of various provinces.

| Count Nicholas | Ripsimia of Armenia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| David | Moses | Aron | Samuel of Bulgaria | Agatha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gavril Radomir | Miroslava | Unknown daughter | Unknown daughter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There is another version of Samuel's origin: the 11th-century historian Stepanos Asoghik wrote that Samuel had only one brother, stating they were both Armenians from the district of Derjan, an Armenian land incorporated into the Byzantine Empire. They were sent to fight the Bulgarians in Macedonia but ended up joining them.[132] This version is supported by the historian Nicholas Adontz, who analyzed the events and facts of the century and concluded that Samuel had only one brother, David.[133] Asoghik's version is also supported by the historian Jordan Ivanov;[134] furthermore, only one brother is mentioned on Samuel's Inscription.

The Arab historian Yahya of Antioch claims that the son of Samuel, Gavril, was assassinated by the leader of the Bulgarians, son of Aaron, because Aaron belonged to the race that reigned over Bulgaria. Asoghik and Yahya clearly distinguish the race of Samuel from the one of Aaron or the race of the Cometopuli from the royal race. According to them, Moses and Aaron are not from the family of the Cometopuli. David and Samuel were of Armenian origin and Moses and Aaron were Armenian on their mother's side.[135]

Samuel's grave was found in 1965 by Greek professor Nikolaos Moutsopoulos in the Church of St Achillios on the eponymous island in Lake Prespa. Samuel had built the church for the relics of the saint of the same name.[136] What is thought to have been the coat of arms of the House of Cometopuli,[137] two perched parrots, was embroidered on his funeral garment.

His remains are kept in the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki,[138] but according to a recent agreement, they may be returned to Bulgaria and buried in the SS. Forty Martyrs Church in Veliko Tarnovo, to rest with the remains of Emperors Kaloyan and Michael Shishman.[139]

Samuel's face was reconstructed to restore the appearance of the 70-year-old Bulgarian ruler. According to the reconstruction, he was a sharp-faced man, bald-headed, with a white beard and moustache.[140]

Samuel is among the most renowned Bulgarian rulers. His military struggle with the Byzantine Empire is marked as an epic period of Bulgarian history. The great number of monuments and memorials in Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia, such as the ones in Petrich and Ohrid, signify the trail this historical figure has left in the memory of the people. Four Bulgarian villages bear his name, as well as Samuel Point[141] on Livingston Island, Antarctica. Samuel is the main figure in at least three major Bulgarian novels by authors Dimitar Talev,[142] Anton Donchev and Stefan Tsanev and also stars in the Greek novel "At the Times of the Bulgarian-Slayer" by Penelope Delta, who closely follows the narrative flow of events as presented by St. Runciman.[143] He is mentioned in the verse of Ivan Vazov,[144] Pencho Slaveykov,[145] and Atanas Dalchev as well.[146]

Nomenclature

editOverview

editSamuel's empire had its heartlands in the modern region of Macedonia, west and southwest of the city of Ohrid, this earlier cultural center of the First Bulgarian Empire. After the area was taken in 1913 after five centuries Ottoman rule by the Kingdom of Serbia, (later Yugoslavia),[147][148] this led to assertions by the nationalist-driven historiography there. Its main agenda was that Samuel's empire was a "Serbian"/"Macedonian Slavic" state, distinct from the Bulgarian Empire.[149] In more recent times the same agenda has been maintained in the Republic of Macedonia, (now North Macedonia).[150]

Practically Serbia did not exist at that time. It became independent under Časlav ca. 930, only to fall ca. 960 under Byzantine and later under Bulgarian rule.[151] In fact, that area was taken for the first time by Serbia centuries later, during the 1280s. Moreover, in Samuel's time, Macedonia as a geographical term referred to part of the region of modern Thrace.[152] The "Macedonian" emperors of that period were Basil II, called "Bulgar-Slayer", and his Byzantine relatives from the Macedonian dynasty, originating from the territory of today's European Turkey.[153] Most of the modern region of Macedonia was then a Bulgarian province known as Kutmichevitsa.[154] The area was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire in 1018 as a new province called Bulgaria.[155]

The very name of "Macedonia" for the modern region was revived only in the 19th century, after it had nearly disappeared during the five centuries of Ottoman rule.[156][157][158][159][160] Until the early 20th century and beyond the majority of the Macedonian Slavs who had clear ethnic consciousness believed they were Bulgarians.[161][162][163][164][165][166] The Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and World War I (1914–1918) left the area divided mainly between Greece and Serbia (later Yugoslavia), which resulted in significant changes in its ethnic composition. The formerly leading Bulgarian community was reduced either by population exchanges or by change of communities' ethnic identity.[167] The Macedonian Slavs were faced with the policy of forced Serbianisation.[168]

Yugoslav agenda

edit20th-century Serbian and afterwards the Yugoslav historiography used the location of Samuel's state mainly on the territory of then Yugoslavia, to reject Bulgarian claims on the region.[169] Thus, the Russian-born Yugoslavian historian George Ostrogorsky distinguished Samuel's Empire from the Bulgarian Empire, referring to it as a "Macedonian Empire", although he recognised that Samuel's state was politically and ecclesiastically a direct descendant of the empire of Simeon I of Bulgaria and Peter I of Bulgaria, and it was regarded by Samuel and the Byzantines as being the Bulgarian Empire itself.[148]

Some historians of the same school, such as the Serbian scholar Dragutin Anastasijević, even claimed that Samuel ruled a separate South Slavic, i.e. Serbian Empire in Macedonia, founded as result of an anti-Bulgarian rebellion.[147] The Serbs tried to popularize the Serbian past of that distinct state and its Serbian rulers.[170] The story continued in Communist Yugoslavia, where a separate Macedonian identity was formed and Samuel was depicted as a Macedonian Tsar.[171] After the breakup of Yugoslavia, these outdated theories have been rejected by authoritative Serbian historians from SANU as Srđan Pirivatrić and Tibor Živković.[172][173][174] Pirivatrić has stated, that incipient Bulgarian identity was available in Samuel's state, and it will rеmain in the area in the next centuries.[175]

North Macedonia's view

editThese fringe theories are still held mainly in North Macedonia, where the official state doctrine refers to an "Ethnic Macedonian" Empire, with Samuel being the first Tsar of the Macedonian Slavs.[150] However, this controversy is ahistorical, as it projects modern ethnic distinctions onto the past.[176] There is no historical support for that assertion.[177] Samuel and his successors were never called by their contemporaries "Macedonians",[178] but simply Bulgarians and rarely Misians. The last designation arose because then Bulgaria occupied traditionally the lands of the former Roman province of Moesia.[179]

Macedonian historians insist also that the emperor Basil II designated the enemies coming from the Samuel’s Empire as “Scythians” in his epitaph and that the designation “Bulgaria” was used for ideological propaganda. This was newly introduced administrative term, by which the emperor ideologically framed the newly acquired territories of the former Bulgarian empire and the former Samuel’s State. In this way the term "Bulgarian" became a projected name for the Samuel’s State itself.[180][181] However, the term “Scythians” normally referred to the "Bulgarians",[182][183] moreover, Samuel and his successors considered their state Bulgarian.[184][185]

Nevertheless, on a meeting in Sofia in June 2017, Prime Ministers Boyko Borisov and Zoran Zaev laid flowers at the monument of Tsar Samuil together, articulating optimism that the two countries can finally resolve their open issues by signing a long-delayed agreement on good-neighborly relations.[186] The governments of Bulgaria and North Macedonia signed the friendship treaty in the same year, which was ratified by the two Parliaments in 2018. On its ground, a bilateral expert committee on historical issues was formed. In February 2019, at a meeting of the committee, involving Bulgarian and Macedonian scientists, the two sides agreed to propose to their governments that Tsar Samuel may be celebrated jointly. The Macedonian side also conceded, that he was Tsar of Bulgaria.[187][188][189][190] Nevertheless in December 2020 North Macedonia's part from the joint committee withdrew from this decision.[191] According to its view, Tsar Samuel had to be portrayed in one way in North Macedonia's textbooks, and in another during joint commemorations.[192]

In August 2022, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of North Macedonia published official recommendations of the Joint Historical Commission operating between the two countries. There, the governments in Sofia and Skopje are offered a joint commemoration of Samuel, who, according to the commission, was the ruler of a large medieval state, which the majority of modern historical scholarship considers to be the Bulgarian empire itself, centered in the territory of today's North Macedonia.[193] In this way the Macedonian members of the Commission not only agreed to identify Samuel's state as Bulgarian, but they also recognized the existence of the Bulgarian ethnicity during the Middle Ages.[194] Despite these facts multiple examples of animosity between Bulgaria and North Macedonia have been registered, due to disputes over Samuil's ethnic affiliation and this issue is still highly sensitive.[195][196]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- 1. Bulgarian ъ can be transliterated a, u, or sometimes â, as in български, balgarski (as below) or bulgarski.

- 2. The work of Vasil Zlatarski, History of the Bulgarian state in the Middle Ages has three editions. The first edition is from 1927 published in Sofia; the second edition is from 1971 and can be found here [3] in Bulgarian; the third edition is from 1994 published in Sofia, ISBN 954-430-299-9

References

edit- ^ Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250, Florin Curta, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521815398, p. 242.

- ^ Spelled thus in Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans; also Ostrogorsky, Treadgold, opp. cit., Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. In French, compare Adontz, Nicholas. "Samuel l'Armenien, Roi des Bulgares", in Études Arméno-Byzantines. Lisbonne: Livraria Bertrand, 1965, pp. 347–407.

- ^ Македонска енциклопедија, том II. Скопје, Македонска академија на науките и уметностите, 2009. ISBN 978-608-203-024-1. стр. 1296

- ^ Stojkov, Stojko (2014) Крунисувањето на Самуил за цар и митот за царот евнух. Гласник на институтот за национална историја, 58 (1–2). pp. 73–92. ISSN 0583-4961.

- ^ A History of the Byzantine state and society, Warren Treadgold, Stanford University Press, 1997, ISBN 0804726302, p. 871.

- ^ Anthony Kaldellis, Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade, Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 0190253223, p. 82.

- ^ One theory is that from 972/976 to 997 Samuel co-ruled with Roman I of Bulgaria, who was the official tsar until 997, when he died in Byzantine captivity. Roman is mentioned as tsar in several historical sources; for example the Annals by Yahya of Antioch call Roman "Tsar" and Samuel "Roman's loyal military chief". However, other historians dispute this theory, as Roman was castrated and so technically could not have claimed the crown. There was also a governor of Skopje called Roman who surrendered the city to the Byzantines in 1004, receiving the title of patrician from Basil II and becoming a Byzantine strategos in Abydus (Skylitzes-Cedr. II, 455, 13), but this could be a mere coincidence of names.

- ^ a b "Samuil of Bulgaria". Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ "Britannica Online – Samuel of Bulgaria". Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ Whittow, Making of Orthodox Byzantium, pp. 387–388.

- ^ Stephenson, P., The legend of Basil the Bulgar-slayer, p. 16, ISBN 0-521-81530-4

- ^ Sullivan. D. F., ed. and tr., The life of St Nikon, Brookline, 1987, pp. 140–142.

- ^ a b Argoe, K. John Kyriotes Geometres, a tenth century Byzantine writer, Madison 1938, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Schlumberger, G, L'épopée byzantine á la fin de dixiéme siécle, 1. Jean Tzimisés; les jeunes années de Basile II, le tueur de Bulgares (969–989), Paris 1896, pp. 643–644.

- ^ a b "The Encyclopedia of World History. 2001. First Bulgarian Empire – Samuil". Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ "About Ohrid". Retrieved 23 May 2008.[dead link]

- ^ The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon, J. B. Bury, Wildside Press LLC, 2004, ISBN 0-8095-9240-1, p. 142.

- ^ A short history of Yugoslavia from early times to 1966, Stephen Clissold, Henry Clifford Darby, CUP Archive, 1968, ISBN 0-521-09531-X, p. 140

- ^ Stephen Runciman, A History of the First Bulgarian Empire, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Prokić, Božidar (1906). Die Zusätze in der Handschrift des Johannes Scylitzes. Codex Vindobonensis hist. graec. LXXIV (in German). München. p. 28. OCLC 11193528.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Southeastern Europe in the early Middle Ages. Florin Curta. p. 241

- ^ Adontz, Nicholas (1938). "Samuel l'Armenien, roi des Bulgares". Mar BCLSMP (in French) (39): 37.

- ^ According to Zlatarski (History of the Bulgarian state, I, 2, pp. 544, 562.) the sons of Peter I were sent in the Byzantine capital in 963 as one of the term to resettle the peace treaty of 927. According to other historians such as Andreev (Who is who in Medieval Bulgaria, p. 41.) the heirs to the Bulgarian throne became hostages per a Bulgarian-Byzantine agreement against the Kievan Rus' in 968.

- ^ Skylitzes records: He [Peter] himself died shortly afterwards, whereupon the sons were sent to Bulgaria to secure the ancestral throne and to restrain the 'children of the counts' from further t. David, Moses, Aaron and Samuel, children of one of the powerful counts in Bulgaria, were contemplating an uprising and were unsettling the Bulgars'

- ^ Blagoeva, B. For the origins of Emperor Samuel (Za proizhoda na tsar Samuil, За произхода на цар Самуил), Исторически преглед, № 2, 1966, стр. 91–94

- ^ "They (the Cometopuli) make their first appearance under the government of Kekaumenos, the strategos of Larissa ... (980–983)": Adontz. "Samuel l'Armenien", 358.

- ^ Ioannes Scylitzes. Historia. 2, pp. 346–347

- ^ Vasilka Tăpkova-Zaimova, Bulgarians by Birth: The Comitopuls, Emperor Samuel and their Successors According to Historical Sources and the Historiographic Tradition, East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, Brill, 2018, ISBN 9004352996, p. 156.

- ^ a b Delev, 12. The decline of the First Bulgarian Empire ( 12. Zalezat na Parvoto Balgarsko Tsarstvo 12. Залезът на Първото българско царство).

- ^ a b c d Bozhilov, Gyuzelev, 1999, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Petrov, P (1962). "Rebellion of Peter and Boyan in 976 and struggle of the Cometopuli with Byzantium (Vosstanie Petra i Boyana v 976 i borba Komitopulov s Vizantiei, Восстание Петра и Бояна в 976 г. и борьба Комитопулов с Византией)". Byzantinobulgarica (in Russian) (1): 130–132.

- ^ Zlatarski, p. 615.

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 334–335.

- ^ П. Хр. Петров, Восстание Петра и Бояна в 976 г. и борьба комитопулов с Византией, Byzantinobulgarica, I, Sofia, 1962, стр. 121–144.

- ^ Й. Иванов, „Български старини из Македония“, София, 1970, стр. 550

- ^ Levchenko, М. V (1951). Precious sources on the Russo-Byzantine relations in the 9th century (Tsenniy istochnih po vaprosu pussko-vizantiyskih otnosheniy v X veke, Ценный источних по вопросу русско-византийских отношений в X веке (in Russian). pp. 66–68.

- ^ Nikolov, G., Centralism and regionalism in Bulgaria during the early Middle ages (end of the 7th— beginning of the 11th century (Tsentralizam i regionalizam v rannosrednovekovna Balgariya (kraya na VII— nachaloto na XI v.), Централизъм и регионализъм в ранносредновековна България (края на VII— началото на ХІ в.)), София 2005, p. 195.

- ^ Westberg, F (1951) [1901]. Die Fragmente des Toparcha Goticus (Anonymus Tauricus aus dem 10. Jahrhundert) (in German). Leipzig: Zentralantiquariat der Dt. Demokrat. Republik. p. 502. OCLC 74302950.

- ^ Petrov, p. 133.

- ^ Petrov, pp. 133–134.

- ^ General history of Stephan from Taron (Vseobshaya istoriya Stepanosa Taronskogo, Всеобщая история Степаноса Таронского (in Russian). pp. 175–176.

- ^ Scylitzes, pp. 434–435. In this context, by "Romans" Skylitzes understands "Byzantines".

- ^ Petrov, P (1959). "Formation and consolidation of the Western Bulgarian state (Obrazuvane i ukrepvane na Zapadnata Balgarska darzhava, Образуване и укрепване на Западната Българска държава)". Гсуифф (in Bulgarian). 53 (2): 169–170.

- ^ Seibt, Untersuchungen, p. 90.

- ^ Rozen, V. R (1972). Emperor Basil the Bulgar-slayer: extractions from Yuhia of Antioch's chronicles (Imperator Vasiliy Bolgaroboytsa: izvecheniya iz letopisi Yahi Antiohijskago, Император Василий Болгаробойца: извлечения из летописи Яхи Антиохийскаго) (in Russian). London: Variorum Reprints. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-902089-39-6.

- ^ Boris II and Roman were sons of Peter I whose dynasty had ruled Bulgaria since the reign of Khan Krum (803–814)

- ^ Petrov, p. 134

- ^ Adontz. "Samuel l'Armenien", p. 353.

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 434–435.

- ^ Prokić, p. 28.

- ^ Rozen, V. R (1972). Emperor Basil the Bulgar-slayer: extractions from Yuhia of Antioch's chronicles (Imperator Vasiliy Bolgaroboytsa: izvecheniya iz letopisi Yahi Antiohijskago, Император Василий Болгаробойца: извлечения из летописи Яхи Антиохийскаго) (in Russian). London: Variorum Reprints. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-902089-39-6.

- ^ Petrov, P (1958). "On the question concerning the authenticity of the Virgin charter and the data it contains (Po vaprosa za awtentichnostta na Virginskata gramota i sadarzhastite se v neya danni, По въпроса за автентичността на Виргинската грамота и съдържащите се в нея данни)". Гсуифф (in Bulgarian). 2 (54): 219–225.

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 435–436.

- ^ Kekaumenos, Strategikon pp. 65–66

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 436.

- ^ Kekaumenos, Strategikon, eds. B. Wassilewsky and P. Jernstedt, St Petersburg, 1896, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Litavrin, G. Soveti i rasskazy Kekavmena. Sochinenie vizantiiskogo polkovodtsa XI veka, Moscow, 1972, pp. 250–252

- ^ Ostrogorsky, G. History of the Byzantine state (Istorija Vizantije, Исторijа Византиje), pp. 391–393.

- ^ Leo Diaconus, Historia, p. 171.

- ^ W. Seibt, Untersuchungen zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte der bulgarischen Kometopulen, Handes Amsorya 89 (1975), pp. 65–98.

- ^ Rozen, p. 21.

- ^ Stephen of Taron, pp. 185–186.[? clarification needed]

- ^ Dennis, Three Treatises, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 436–438.

- ^ Gilferding, А (1868). Letters from the history of Serbians and Bulgarians (Pisma ob istorii serbov i bolgar, Письма об истории сербов и болгар) (in Russian). Москва. p. 209. OCLC 79291155.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ioannis Geometrae Carmina varia. Migne, Patrol. gr., t. 106, col. 934

- ^ "Roman Emperors – Basil II". Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ Al-Rudrawari, pp. 28–35.

- ^ Ostrogorsky, G. History of the Byzantine state (Istorija Vizantije, Исторijа Византиje), pp. 397–398.

- ^ E Codd. Manuscriptis Bibliothecae Regiae Parisiensis, J.A.Cramer (ed.), 4 Vols (Oxford, 1839–1841), Vol 4, pp. 271, 282.

- ^ Rozen, p. 27.

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 446.

- ^ John Geometres: Anecdota Graeca, E Codd. Manuscriptis Bibliothecae Regiae Parisiensis, J.A.Cramer (ed.), 4 Vols (Oxford, 1839–1841), Vol 4, pp. 271–273, 282–283.

- ^ Zlatarski, pp. 645–647.

- ^ Vasilyevskiy, V. G. History of the years 976–986 (K istorii 976–986 godov, К истории 976–986 годов) (in Russian). p. 83.

- ^ Ioannes Geometer. Carmina, col. 920A.

- ^ Ostrogorsky, Byzantine State, pp. 303–308

- ^ Zlatarski, pp. 651–652.

- ^ Yahya, PO 23 (1932), pp. 430–431.

- ^ Stephen of Taron, p. 198.[? clarification needed]

- ^ Rozen, p. 34.

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 449

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 449–450

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 450

- ^ Stephenson, P., The legend of Basil the Bulgar-slayer, p. 17, ISBN 0-521-81530-4

- ^ Andreev, 1999, pp. 331–334.

- ^ Rozen, p. 43.

- ^ Шишић 1928, p. 330.

- ^ Duichev, Iv. (1942). "Correspondence of Pope Innocent III with the Bulgarians (Prepiska na papa Inokentii III s balgarite, Преписка на папа Инокентий III с българите.)". Гсуифф (in Bulgarian) (38): 22–23. There is no direct evidence for this recognition, but in his correspondence with Pope Innocent III two centuries later, the Bulgarian Emperor Kaloyan pointed out that his predecessors Peter and Samuel had received imperial recognition by Rome.

- ^ a b Шишић 1928, p. 331.

- ^ Шишић 1928, p. 334.

- ^ a b Skylitzes, p. 451.

- ^ Venedikov, Iv. (1973). "The first wedlock of Gavril Radomir (Parviyat brak na Gavril Radomir, Първият брак на Гаврил Радомир)". Collection in memory of Аl. Burmov (in Bulgarian). pp. 144–149. OCLC 23538214.

- ^ Holmes, Basil II and the government of the empire, vii, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Antoljak, Samuel and his estate, pp. 78–80.

- ^ R. V. Rozen, Emperor Basil the Bulgar-slayer (Imperator Vasiliy Bolgaroboytsa, Император Василий Болгаробойца), p. 34.

- ^ Аndreev, J. The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars (Balgarskite hanove i tsare, Българските ханове и царе), Veliko Tarnovo, 1996, p. 125. ISBN 954-427-216-X

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 452.

- ^ Ibidem. II, р. 452.

- ^ a b c Prokić, p. 30.

- ^ Zonaras, ibid., IV, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Skyl. – Cedr., ibid., II, pp. 452–453.

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 452–454.

- ^ Legenda Saneti Gerhardi episcopi, p. 489.

- ^ Venedikov, p. 150.

- ^ Legenda Saneti Gerhardi episcopi, pp. 492–493.

- ^ Venedikov, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b Skylitzes, p. 454.

- ^ Ivanov, Jordan (1970) [1931]. Bulgarian historical monuments in Macedonia (Balgarski starini iz Makedoniya, Български старини из Македония) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo. p. 557. OCLC 3736478.

- ^ Skylitzes, pp. 454–455.

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 455.

- ^ Zlatarski, pp. 685–687.

- ^ Actes d'Iviron I. Des origines au milieu du XIe siècle, Archives de l'Athos XIV, eds. J.Lefort, N.Oikonomides, D.Papachryssanthou, H.Métrévéli (Paris, 1985), doc. 8

- ^ Ostrogorsky, G. History of the Byzantine state (Istorija Vizantije, Исторijа Византиje), pp. 404–405.

- ^ Gilferding, p. 250.

- ^ a b Златарски, pp. 689–690.

- ^ a b c Skylitzes, p. 457.

- ^ Daulaurier, p. 37.

- ^ Selected sources for the Bulgarian history, Volume II: The Bulgarian states and the Bulgarians in the Middle Ages (Podbrani izvori za balgarskata istoriya, Tom II: Balgarskite darzhavi i balgarite prez srednovekovieto, Подбрани извори за българската история, Том II: Българските държави и българите през средновековието), p. 66.

- ^ Пириватрич, Самуиловата държава, p. 136.

- ^ Fol, Al.; et al. (1983). Short history of Bulgaria (Kratka istoriya na Balgariya, Кратка история на България) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo. p. 71. OCLC 8553856.

- ^ Conquest of Bulgaria by Byzantium (end of the 10th-beginning of the 11th century) in the Russian chronography, HV-XVI c. (Zavoevenie Bolgarii Vizantiei (konets X-nachalo XI v.) v russkom hronografe, HV-XVI vv; ЗАВОЕВАНИЕ БОЛГАРИИ ВИЗАНТИЕЙ (КОНЕЦ Х-НАЧАЛО XI в.) В РУССКОМ ХРОНОГРАФЕ, XV-XVI вв.) L. V. Gorina (Moscow State University)- in Russian [1]

- ^ Duichev, Ivan (1943–1946). In the old Bulgaria literature (Iz starata balgarska knijnina, Из старата българска книжнина) (in Bulgarian). Vol. 2. Sofia: Hemus. p. 102. OCLC 80070403.

- ^ Cecaumenes. Strategion, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Zlatarski, p. 699.

- ^ Pavlov, Plamen (2002). Emperor Samuil and the "Bulgarian epopee" (in Bulgarian). Sofia, Veliko Tarnovo: VMRO Rusa. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009.

- ^ Themes in the Byzantine Empire under Basil II Themes under Basil II Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zlatarski, pp. 742–744.

- ^ a b PmbZ, Samuel Kometopulos (#26983).

- ^ PmbZ, Kosara (#24095).

- ^ "V. Zlatarski – Istorija 1 B – Priturka 15". Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Asoghik (Stepanos de Taron). L'histoire universelle, Paris, 1859. Translation in German, Leipzig, 1907.

- ^ Adontz. "Samuel l'Armenien", pp. 347–407.

- ^ Иванов, Йордан (Jordan Ivanov). Произход на цар Самуиловия род (The origin of the family of the king Samuel). In: Сборник в чест на В. Н. Златарски, София, 1925.

- ^ Adontz. "Samuel l'Armenien", pp. 387–390.

- ^ "Prof. Kazimir Popkonstantinov: The offer for exchange of Samuel's remains is a provocation from Greece" (in Bulgarian). "Focus" Agency. 15 February 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ^ Edouard Selian. The Coat of Arms of Emperor Samuel. In: American Chronicle, 21 March 2009 The Coat of Arms of Emperor Samuel and Macedonian Digest, Edition 40 – April 2009 [2]

- ^ (in Greek) Σταύρος Τζίμας (7 October 2014). "Τα οστά του Σαμουήλ, η ανταλλαγή και το παρασκήνιο". Καθημερινή; Retrieved 7 October 2014

- ^ Dobrev, Petar (18 April 2007). "The remains of Tsar Samuel will after all go to Tarnovo – to the grave of Kaloyan" (in Bulgarian). e-vestnik.bg. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ^ "The appearance of Tsar Samuel is resurrected in Moscow" (in Bulgarian). Radio Bulgaria. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ^ "Republic of Bulgaria, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Antarctic Place-names Commission, Bulgarian Antarctic Gazetteer Samuel Point". Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Talev, Dimitar (1998). Samuil – Bulgarian Tsar (Samuil – tsar balgarski, Самуил – цар български). Аbagar. ISBN 954-584-238-5.

- ^ "S. Runciman - A history of the First Bulgarian empire - Preface".

- ^ Ivan Vazov "The Volunteers at Shipka (in Bulgarian)". Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ Pencho Slaveikov "Tsar Samuil (in Bulgarian)". Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ "Towards the Motherland (in Bulgarian)". Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ^ a b Anastasiević, D. N. Hypothesis on Western Bulgaria (Hipoteza o Zapadnoj Bugarskoj, Хипотеза о Западноj Бугарскоj), Glasnik Skopskog nauchnog drushtva, b. III, Skopie, 1928.

- ^ a b History of the Byzantine State (Rutgers, 1969), p. 301-302.

- ^ David Ricks, Michael Trapp as ed., Dialogos: Hellenic Studies Review, Routledge, 2014; ISBN 1317791789, p. 36.

- ^ a b An outline of Macedonian history from ancient times to 1991. Macedonian Embassy London. Retrieved on 28 April 2007.

- ^ Jim Bradbury, The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare, Routledge Companions to History, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 1134598475, p. 172.

- ^ The migrations during the early Byzantine centuries also changed the meaning of the geographical term Macedonia, which seems to have moved to the east together with some of the non-Slavic population of the old Roman province. In the early 9th century an administrative unit (theme) of Makedonikon was established in what is now Thrace (split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey) with Adrianople as its capital. It was the birthplace of Emperor Basil I (867–886), the founder of the so-called Macedonian dynasty in Byzantinum. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, p. iii

- ^ By the beginning of the 9th century the theme of Macedonia, with its capital at Adrianople consisted not of Macedonian but of Thracian territories. During the Byzantine period the Macedonia proper corresponded to the themes of Thessalonica and Strymon. Brill's Companion to Ancient Macedon: Studies in the Archaeology and History of Macedon, 650 BC – 300 AD, Robin J. Fox, Robin Lane Fox, Brill, 2011, ISBN 9004206507, p. 35.

- ^ The entry of the Slavs into Christendom: an introduction to the medieval history of the Slavs, A. P. Vlasto, CUP Archive, 1970, ISBN 0-521-07459-2, p. 169.

- ^ When the barbarian invasions started in the fourth through seventh centuries AD in the Balkans, the remnants of the Hellenes who lived in Macedonia were pushed to eastern Thrace, the area between Adrianople (presently the Turkish city of Edirne) and Constantinople. This area would be called theme of Macedonia by the Byzantines... whereas the modern territory of Rep. of North Macedonia was included in the theme of Bulgaria after the destruction of Samuels Bulgarian Empire in 1018. Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996, Chris Kostov, Peter Lang, 2010, ISBN 3034301960, p. 48.

- ^ The ancient name 'Macedonia' disappeared during the period of Ottoman rule and was only restored in the nineteenth century originally as geographical term. The Oxford Handbook of the History of Nationalism, John Breuilly, Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 0199209197, p. 192.

- ^ The region was not called "Macedonia" by the Ottomans, and the name "Macedonia" gained currency together with the ascendance of rival nationalism. Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Victor Roudometof, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 89.

- ^ The Greeks were amongst the first to define these lands since the beginning of the 19th century. For educated Greeks, Macedonia was the historical Greek land of kings Philip and Alexander the Great. John S. Koliopoulos, Thanos M. Veremis, Modern Greece: A History since 1821. A New History of Modern Europe, John Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN 1444314831, p. 48.

- ^ Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans, Vol. 2: Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0521274591.

However, in the nineteenth century the term Macedonian was used almost exclusively to refer to the geographic region

- ^ By the Middle Ages Macedonia's location had been forgotten and designated in areas mostly outside the original Macedonian kingdom... Under Turkish rule Macedonia vanished completely from administrative terminology and survived only as a legend in the oral Greek traditions… Rediscovered by travelers, cartographers and diplomats after centuries of being ignored or forgotten, misplaced or misunderstood, Macedonia and its inhabitants, have never since the beginning of the 20th century, ceased being imagined and invented. John S. Koliopoulos, Plundered Loyalties: World War II and Civil War in Greek West Macedonia, NYU Press, 1999, ISBN 0814747302, p. 1.

- ^ "Until the late 19th century both outside observers and those Bulgaro-Macedonians who had an ethnic consciousness believed that their group, which is now two separate nationalities, comprised a single people, the Bulgarians. Thus the reader should ignore references to ethnic Macedonians in the Middle ages which appear in some modern works. In the Middle ages and into the 19th century, the term ‘Macedonian’ was used entirely in reference to a geographical region. Anyone who lived within its confines, regardless of nationality could be called a Macedonian...Nevertheless, the absence of a national consciousness in the past is no grounds to reject the Macedonians as a nationality today." "The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century," John Van Antwerp Fine, University of Michigan Press, 1991, ISBN 0472081497, pp. 36–37.

- ^ "At the end of the World War I there were very few historians or ethnographers, who claimed that a separate Macedonian nation existed... Of those Macedonian Slavs who had developed then some sense of national identity, the majority probably considered themselves to be Bulgarians, although they were aware of differences between themselves and the inhabitants of Bulgaria... The question as of whether a Macedonian nation actually existed in the 1940s when a Communist Yugoslavia decided to recognize one is difficult to answer. Some observers argue that even at this time it was doubtful whether the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves to be a nationality separate from the Bulgarians." The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world, Loring M. Danforth, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, pp. 65–66.

- ^ "Most of the Slavophone inhabitants in all parts of divided Macedonia, perhaps a million and a half in all – had a Bulgarian national consciousness at the beginning of the Occupation; and most Bulgarians, whether they supported the Communists, VMRO, or the collaborating government, assumed that all Macedonia would fall to Bulgaria after the WWII. Tito was determined that this should not happen. The first Congress of AVNOJ in November 1942 had parented equal rights to all the 'peoples of Yugoslavia', and specified the Macedonians among them."The struggle for Greece, 1941–1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1-85065-492-1, p. 67.

- ^ "Yugoslav Communists recognized the existence of a Macedonian nationality during WWII to quiet fears of the Macedonian population that a communist Yugoslavia would continue to follow the former Yugoslav policy of forced Serbianization. Hence, for them to recognize the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians would be tantamount to admitting that they should be part of the Bulgarian state. For that the Yugoslav Communists were most anxious to mold Macedonian history to fit their conception of Macedonian consciousness. The treatment of Macedonian history in Communist Yugoslavia had the same primary goal as the creation of the Macedonian language: to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate national consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia." For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- ^ "No doubt, the vast majority of the Macedonian peasants, being neither communists nor members of IMRO (United), had not been previously affected by Macedonian national ideology. The British officials who attempted to tackle this issue in the (late) 1940s noted the pro-Bulgarian sentiment of many peasants and pointed out that Macedonian nationhood rested ‘on rather shaky historical and philological foundations’ and, therefore, had to be constructed by the Macedonian leadership." Livanios, D. (2008), The Macedonian Question: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939–1949.: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0191528722, p. 206.

- ^ As David Fromkin (1993, p. 71) confirms: “even as late as 1945, Slavic Macedonia had no national identity of its own." Nikolaos Zahariadis (2005) Essence of Political Manipulation: Emotion, Institutions, & Greek Foreign Policy, Peter Lang, p. 85, ISBN 0820479039.

- ^ Ivo Banac, The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics, Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801494931, p. 33

- ^ Dejan Djokić, Yugoslavism: histories of a failed idea, 1918–1992, p. 123, at Google Books

- ^ Pieter Troch, Nationalism and Yugoslavia: Education, Yugoslavism and the Balkans before World War II, I.B.Tauris, 2015, ISBN 0857737686,Chapter 5: Merging Tribal Histories.

- ^ Nada Boskovska, Yugoslavia and Macedonia Before Tito: Between Repression and Integration, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017, ISBN 1786730731, p. 50–51.

- ^ Svetozar Rajak, Konstantina E. Botsiou, Eirini Karamouzi, Evanthis Hatzivassiliou ed. The Balkans in the Cold War. Security, Conflict and Cooperation in the Contemporary World, Springer, 2017, ISBN 1137439033, p. 313.

- ^ Istorijski časopis 2002, br. 49, str. 9–25, izvorni naučni članak, Pohod bugarskog cara Samuila na Dalmaciju. Živković Tibor D. SANU – Istorijski institut, Beograd.

- ^ Pirivatrić, Samuilova država: obim i karakter, Самуилова држава: обим и карактер.

- ^ Vizantološki institut (Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti), Naučno delo, 1997, st. 253–256.

- ^ Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 1, From Ancient Times to the Ottoman Invasions), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888435, p. 345.

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander; Brand, Charles M. (1991). "Samuel of Bulgaria". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1838. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- ^ D. Hupchick, The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism, Springer, 2002, ISBN 0312299133, p. 53.

- ^ Ioannis Tarnanidis, The Macedonians of the Byzantine period, (Aristotelian University of Thessaloniki, Greece) in John Burke and Roger Scott as edidors, Byzantine Macedonia: Identity, Image and History: Papers from the Melbourne Conference July 1995, BRILL, 2000, ISBN 900434473X, pp. 29–50; 48.

- ^ Paul Stephenson, Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204, American Council of Learned Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0521770173, p. 78.

- ^ Panov 2019, p. 88.

- ^ B. Panov, Mitko (2022). "Ideology behind the Naming: On the Origin of Basil II's Appellation 'Scythicus'". Studia Ceranea. 12: 739–750. doi:10.18778/2084-140X.12.02.

- ^ Amelia Robertson Brown, Bronwen Neil (ed.), Byzantine Culture in Translation. Brill, 2017, ISBN 9789004349070, p. 109.

- ^ Grzegorz Bartusik, Jakub Morawiec, Radosław Biskup (ed.), Adam of Bremen’s Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum. Origins, Reception and Significance, 2022. Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781000610383, p. 236.

- ^ Dennis P. Hupchick, The Bulgarian-Byzantine Wars for Early Medieval Balkan Hegemony: Silver-Lined Skulls and Blinded Armies, Springer, 2017, ISBN 3319562061, p. 314.

- ^ Crampton, R. J. A Concise History of Bulgaria (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-61637-9, p. 15.

- ^ "Council of Ministers of the Republic of Bulgaria, Government Information Service, 20 June 2017". Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ България и Северна Македония да честват заедно цар Самуил, предложи съвместната комисия в-к Дневник, 23 фев 2019.

- ^ Проф. Иван Илчев: Македонците в двустранната комисия признаха, че цар Самуил е български владетел. Труд онлайн; 10.12.2018

- ^ Драги Георгиев: Цар Самуил својот легитимитет го црпи од Бугарската царска круна. 05 јануари 2019, Канал 5 ТВ.

- ^ "Цар Самуил легитимен претставник на Бугарското царство". Фактор Портал. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Вместо напредък Скопие се върна при цар Самуил (Oбзор, видео) 24chasa.bg, 04.12.2020.

- ^ Naoum Kaychev, On Unifying Around Our Common History - Tsar Samuil Erga Omnes ResPublica, 07 April, 2021.

- ^ Пробив в историческата комисия: Цар Самуил е владетел на българско царство, Dir.bg. 15.08.2022 Archived 15 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Mitko B. Panov et al., 2021. "Macedonian Nation Between Self-Identity and Euro-Atlantic Integration: Implications of the Agreements with Bulgaria and Greece," Societies and Political Orders in Transition, in: Branislav Radeljić & Carlos González-Villa (ed.), Researching Yugoslavia and its Aftermath, pp. 223–252, (228) Springer.

- ^ Macedonian Medieval Epic Annoys Bulgaria 17.02.2014, Balkan Insight (BIRN)

- ^ Катерина Блажевска, Бугарски историчари ликуваат: Ова е прва победа! 16.08.2022, Deutsche Welle.

Sources

edit- Adontz, Nicholas (1965). "Samuel l'Armenien, Roi des Bulgares". Études Arméno-Byzantines (in French). Lisbonne: Livraria Bertrand.

- Andreev, Jordan; Milcho Lalkov (1996). The Bulgarian Khans and Tsars (in Bulgarian). Abagar. ISBN 954-427-216-X.

- Cheynet, Jean-Claude (1990). Pouvoir et contestations a Byzance (963–1210) (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Delev, Petar; Valeri Katsunov; Plamen Mitev; Evgeniya Kalyanova; Iskra Baeva; Boyan Dobrev (2006). "12. The decline of the First Bulgarian Empire". History and civilization for 11. grade (in Bulgarian). Trud, Sirma. ISBN 954-9926-72-9.

- Dimitrov, Bozhidar (1994). "Bulgarian epic endeavours for independence 968–1018". Bulgaria: illustrated history. Sofia: Borina. ISBN 954-500-044-9.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. "Bulgaria after Symeon, 927–1018". The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 188–200. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Lalkov, Milcho (1997). "Tsar Samuil (997–1014)". Rulers of Bulgaria. Kibea. ISBN 954-474-098-8.

- Lang, David Marshal, The Bulgarians: from pagan times to the Ottoman conquest. Boulder, Colo. : Westview Press, 1976. ISBN 0-89158-530-3

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes; Ludwig, Claudia; Pratsch, Thomas; Zielke, Beate (2013). Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit Online. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Nach Vorarbeiten F. Winkelmanns erstellt (in German). Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Ostrogorsky, George, History of the Byzantine State. tr. (from the German) by Joan Hussey, rev. ed., Rutgers Univ. Press, 1969.

- Pavlov P., Samuil and the Bulgarian epopee (in Bulgarian), Sofia – Veliko Tarnovo, 2002

- Pirivatrić, Srđan; Božidar Ferјančić (1997). Samuil's state: appearance and character (in Serbian). Belgrade: Institute of Byzantine Studies SANU. OCLC 41476117. Excerpt from the Bulgarian translation.

- Runciman, Steven (1930). "The end of an empire". A history of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: George Bell & Sons. OCLC 832687.

- Schlumberger, G. (1900). "t. 2 Basile II-eme – le Tueur des Bulgares". L'epopee byzantine a la fin du X-me siecle (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Tsanev, Stefan (2006). "Chapter XIII. (972–1014). Heroic agony. Tsar Roman, Tsar Samuil.". Bulgarian Chronicles (in Bulgarian). Sofia, Plovdiv: Тrud, Zhanet 45. ISBN 954-528-610-5.

- Zlatarski, Vasil (1971) [1927]. История на българската държава през средните векове. Том I. История на Първото българско царство, Част II. От славянизацията на държавата до падането на Първото царство (852–1018) [History of Bulgaria in the Middle Ages. Vol. 1. History of the First Bulgarian Empire, Part 2. From the Slavicization of the state to the fall of the First Empire (852–1018)]. Sofia: Nauka i izkustvo. OCLC 67080314.

- "1.3. The Bulgarian capitals in the Macedonian lands. The southwestern Bulgarian lands.". The Bulgarians and Bulgaria (in Bulgarian). Ministry of Internal Affairs, Тrud, Sirma. 2005. Archived from the original on 10 November 2005.

- Wortley, John, ed. (2010). John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811–1057. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76705-7.

- Шишић, Фердо, ed. (1928). Летопис Попа Дукљанина (Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja). Београд–Загреб: Српска краљевска академија.

- Кунчер, Драгана (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. Vol. 1. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Живковић, Тибор (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. Vol. 2. Београд–Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Panov, Mitko B. (2019). The Blinded State: Historiographic Debates about Samuel Cometopoulos and His State (10th–11th Century); Volume 55 of East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450. Leiden/Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9004394292.

External links

edit- (in Russian) Летопис попа Дуклянина

- (in Russian) Яхъя Антиохийский, Летопись 1–6, 7–17

- (in Russian) Отрывок из Иоанна Скилицы о битве у горы Беласица

- Detailed list of Bulgarian rulers (PDF)

- John Skylitzes, Synopsis Historion: The Battle of Kleidion Archived 13 July 2001 at the Wayback Machine

- Catherine Holmes, Basil II (A.D. 976–1025) Archived 13 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja

- Map of Europe in 1000.

- Naum Kaychev: On Unifying Around Our Common History – Tsar Samuil Erga Omnes, respublica.edu.mk, 7. april 2021