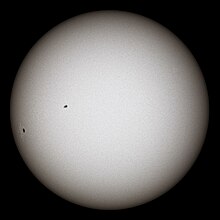

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: NASA

Canopus (/kəˈnoʊpəs/; α Car, α Carinae, Alpha Carinae) is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina, and the second brightest star in the night-time sky, after Sirius. Canopus's visual magnitude is −0.72, and it has an absolute magnitude of −5.65. Canopus is a supergiant of spectral type F. Canopus is essentially white when seen with the naked eye (although F-type stars are sometimes listed as "yellowish-white"). It is located in the far southern sky, at a declination of −52° 42' (2000) and a right ascension of 06h24.0m. Its name comes from the mythological Canopus, who was a navigator for Menelaus, king of Sparta. Canopus is the most intrinsically bright star within approximately 700 light years, and it has been the brightest star in Earth's sky during three different epochs over the past four million years. Other stars appear brighter only during relatively temporary periods, during which they are passing the Solar System at a much closer distance than Canopus. About 90,000 years ago, Sirius moved close enough that it became brighter than Canopus, and that will remain the case for another 210,000 years. But in 480,000 years, Canopus will once again be the brightest, and will remain so for a period of about 510,000 years. Selected article - Photo credit: User:Nikolang

A white dwarf, also called a 'degenerate dwarf, is a small star composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. They are very dense; a white dwarf's mass is comparable to that of the Sun and its volume is comparable to that of the Earth. Its faint luminosity comes from the emission of stored thermal energy. In January 2009, the Research Consortium on Nearby Stars project counted eight white dwarfs among the hundred star systems nearest the Sun. The unusual faintness of white dwarfs was first recognized in 1910 by Henry Norris Russell, Edward Charles Pickering, and Williamina Fleming; the name white dwarf was coined by Willem Luyten in 1922. White dwarfs are thought to be the final evolutionary state of all stars whose mass is not high enough to become a neutron star—over 97% of the stars in our galaxy. After the hydrogen–fusing lifetime of a main-sequence star of low or medium mass ends, it will expand to a red giant which fuses helium to carbon and oxygen in its core by the triple-alpha process. If a red giant has insufficient mass to generate the core temperatures required to fuse carbon, around 1 billion K, an inert mass of carbon and oxygen will build up at its center. After shedding its outer layers to form a planetary nebula, it will leave behind this core, which forms the remnant white dwarf. Usually, therefore, white dwarfs are composed of carbon and oxygen. If the mass of the progenitor is above 8 solar masses but below 10.5 solar masses, the core temperature suffices to fuse carbon but not neon, in which case an oxygen-neon–magnesium white dwarf may be formed.appear to have been formed by mass loss in binary systems. The material in a white dwarf no longer undergoes fusion reactions, so the star has no source of energy, nor is it supported by the heat generated by fusion against gravitational collapse. It is supported only by electron degeneracy pressure, causing it to be extremely dense. The physics of degeneracy yields a maximum mass for a non-rotating white dwarf, the Chandrasekhar limit—approximately 1.4 solar mass—beyond which it cannot be supported by electron degeneracy pressure. A carbon-oxygen white dwarf that approaches this mass limit, typically by mass transfer from a companion star, may explode as a Type Ia supernova via a process known as carbon detonation. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA/WikiSky

Messier 10 or M10 (also designated NGC 6254) is a globular cluster in the constellation of Ophiuchus. It was discovered by Charles Messier. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography -Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, FRS (/ˌtʃʌndrəˈʃeɪkɑːr/ ; Tamil: சுப்பிரமணியன் சந்திரசேகர்; October 19, 1910 – August 21, 1995) was an Indian-American astrophysicist who, with William A. Fowler, won the 1983 Nobel Prize for Physics for key discoveries that led to the currently accepted theory on the later evolutionary stages of massive stars. Chandrasekhar was the nephew of Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930. Chandrasekhar's most notable work was the astrophysical Chandrasekhar limit. The limit describes the maximum mass of a white dwarf star, ~ 1.44 solar mass, or equivalently, the minimum mass above which a star will ultimately collapse into a neutron star or black hole (following a supernova). The limit was first calculated by Chandrasekhar in 1930 during his maiden voyage from India to Cambridge, England, for his graduate studies. In 1999, the NASA named the third of its four "Great Observatories" after Chandrasekhar. The Chandra X-ray Observatory was launched and deployed by Space Shuttle Columbia on July 23, 1999. The Chandrasekhar number, an important dimensionless number of magnetohydrodynamics, is named after him. The asteroid 1958 Chandra is also named after Chandrasekhar. American astronomer Carl Sagan, who studied Mathematics under Chandrasekhar, at the University of Chicago, praised him in the book The Demon-Haunted World: "I discovered what true mathematical elegance is from Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar." From 1952 to 1971 Chandrasekhar also served as the editor of the Astrophysical Journal. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1983 for his studies on the physical processes important to the structure and evolution of stars. Chandrasekhar accepted this honor, but was upset that the citation mentioned only his earliest work, seeing it as a denigration of a lifetime's achievement. He shared it with William A. Fowler.

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |