Cube is a 1997 Canadian science fiction horror film directed and co-written by Vincenzo Natali.[8] A product of the Canadian Film Centre's First Feature Project,[9] Nicole de Boer, Nicky Guadagni, David Hewlett, Andrew Miller, Julian Richings, Wayne Robson, and Maurice Dean Wint star as seven individuals trapped in a bizarre and deadly labyrinth of cube-shaped rooms.

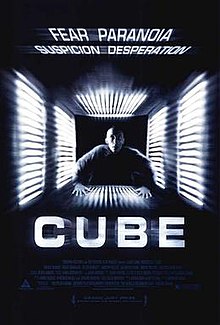

| Cube | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Vincenzo Natali |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Derek Rogers[1] |

| Edited by | John Sanders[1] |

| Music by | Mark Korven[1] |

Production company | Cube Libre[2] |

| Distributed by | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 90 minutes[4] |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $350,000 CAD[5] |

| Box office | $9 million[6][7] |

Cube gained notoriety and a cult following for its surreal and Kafkaesque setting in industrial, cube-shaped rooms. It received generally positive reviews and led to a series of films. A Japanese remake was released in 2021.

Plot

editA man named Alderson awakens in a room that has hatches on each wall and floor, each leading to other rooms. He enters another room, and is killed by a trap.

Five different people all meet in another room: men Quentin, Rennes, and Worth, and women Leaven and Holloway. Quentin warns the group that he has seen traps in some of the other rooms. Leaven notices each hatch has plates with three sets of numbers etched into them. Rennes tests his theory that each trap could be triggered by detectors by throwing his boot into a room, and started moving through the safe rooms. This works for motion detectors and pressure sensors, but fails to trigger the trap in one of the rooms and he is killed by acid trap. The group realizes each trap is triggered by a different type of sensor.

Quentin believes each person was chosen to be there. Leaven hypothesizes that rooms whose plates contain prime numbers are trapped. They encounter a mentally disabled man named Kazan, whom Holloway insists be brought along. Tension rises among the group, as well as the mystery of the maze's purpose. Worth admits to Quentin he was hired to design the maze’s shell, claims The Cube was created accidentally by a bureaucracy, and guesses that its original purpose has been forgotten and that they have only been placed inside to justify its existence.

Worth's knowledge of the exterior dimensions allows Leaven to calculate that the Cube has 17,576 rooms, plus a "bridge" room that would connect to the shell, and thus, the exit. She realizes that the numbers may indicate each room's coordinates. The group travels to the edge but realize every room there is trapped. They successfully traverse a room with a trap. Holloway defends Kazan from Quentin's threats.

The group reaches the edge, but can see no exit. Holloway tries to swing over to the shell using a rope made of clothing. The Cube shakes, causing the rope to slip; Quentin catches it at the last second and pulls her up, but then deliberately drops her to her death, telling the others that she slipped.

Quentin picks up Leaven and carries her to a different room in her sleep, intending to abandon Kazan and Worth. He tries to assault her, but Worth follows and attacks him. Quentin counters savagely, then throws Worth down a hatch to a different room. Upon landing, Worth starts laughing hysterically; Rennes' corpse is in the room, proving they have moved in a circle. Quentin is horrified, but Worth realizes the room Rennes died in has now moved to the edge of the maze, meaning they haven't gone in a circle at all. Instead, the rooms are moving, and will eventually line up with the exit. Leaven deduces that traps are not tagged by prime numbers, but by powers of prime numbers. Kazan is revealed as an autistic savant who can calculate factorizations in his head instantaneously. Leaven and Kazan guide the group through the cube to the bridge. Worth then traps Quentin in a hatch. He catches up and attempts to attack them, but Worth opens a hatch under him from the room below. All but Quentin travel to the bridge where they open the hatch, revealing a bright light.

Quentin reappears and impales Leaven with a lever. Worth attacks Quentin, who wounds him in the struggle and pursues Kazan to the exit. Worth grabs Quentin's legs, keeping him trapped in the doorway. The bridge moves, killing Quentin. Worth crawls to Leaven to stay by her side, as Kazan wanders out into the light.

Cast

editThe cast is of Canadian actors who were relatively unknown in the United States at the time of the film's release.[10] Each character's name is connected with a real-world prison: Quentin (San Quentin, California), Holloway (UK), Kazan (Russia), Rennes (France), Alderson (Alderson, West Virginia), Leaven & Worth (Leavenworth, Kansas).[11]

- Andrew Miller as Kazan, an autistic savant and mental calculator

- David Hewlett as David Worth, an office worker and unwitting designer of the Cube's outer shell

- Maurice Dean Wint as Quentin, a police officer who aggressively takes charge

- Nicole de Boer as Leaven, a young mathematics student

- Nicky Guadagni as Dr. Helen Holloway, a free clinic doctor and conspiracy theorist

- Wayne Robson as Rennes, an escape artist who has broken out of seven prisons

- Julian Richings as Alderson, the first killed in the Cube and the only one not to meet the others

On casting Maurice Dean Wint as Quentin, Natali's cost-centric approach sought an actor for a split-personality role of hero and villain. Wint was considered the standout among the cast and was confident that the film would be a breakthrough for the Canadian Film Centre.[12]

Development

editPre-production

editAlfred Hitchcock's Lifeboat, which was shot entirely in a lifeboat with no actor standing at any point, was reportedly an inspiration for the film.[13]

Director Vincenzo Natali did not have confidence in financing a film. He cost-reduced his pitch with a single set reused as many times as possible, with the actors moving around a virtual maze.[14] As the most expensive element, a set with a cube and a half was built off the floor, to allow the surroundings to be lit from behind all walls of the cube.[15] In 1990, Natali had had the idea to make a film "set entirely in hell", but in 1994 while working as a storyboard artist's assistant at Canada's Nelvana animation studio, he completed the first script for Cube. The initial draft had a more comedic tone, surreal images, a cannibal, edible moss growing on the walls, and a monster that roamed the Cube. Roommate and childhood filmmaking partner Andre Bijelic helped Natali strip the central idea to its essence of people avoiding deadly traps in a maze. Scenes outside the cube were deleted, and the identity of the victims changed. In some drafts, they were accountants and in others criminals, with the implication that their banishment to the Cube was part of a penal sentence. One of the most important dramatic changes was the removal of food and water for a more urgent escape.[16]

After writing Cube, Natali developed the short film Elevated. It is set in an elevator to show investors how Cube would hypothetically look and feel. Cinematographer Derek Rogers developed strategies for shooting in the tightly confined elevator, which he later reused on a Toronto soundstage for Cube.[17]

Casting started with Natali's friends, and budget limitations allowed for only one day of script reading prior to shooting. As it was filmed relatively quickly with well prepared actors, there are no known outtake clips.[15]

Filming

editThe film was shot in Toronto, Ontario[18] in 21 days,[14] with 50% of the budget as C$350,000[10] to C$375,000 in cash[15] and the other 50% as donated services, for a total of C$700,000.[19] Natali considered the cash figure to be deceptive, because they deferred payment on goods and services, and got the special effects at no cost.[20]

The set's warehouse was near a train line, and its noise was incorporated into the film as that of the cubes moving.[21] To change the look of each room, some scenes were shot with wide lens, and others are long lens and lit with different colors, for the illusion of traversing a maze.[13] Nicole de Boer said that the white room was more comforting to actors at the start of a day's filming, compared to the red room which induced psychological effects on the cast during several hours in the confined space.[22]

Only one cube set was actually built, with each of its sides measuring 14 feet (4.3 m) in length, with only one working door that could actually support the weight of the actors. The colour of the room was changed by sliding panels.[23] This time-consuming procedure determined that the film was not shot in sequence, and all shots taking place in rooms of a specific color were shot separately. Six colors of rooms were intended to match the recurring theme of six throughout the film; five sets of gel panels, plus pure white. However, the budget did not stretch to the sixth gel panel, and so the film has only five room colors. Another partial cube was made for shots requiring the point of view of standing in one room and looking into another.[24]

The small set created technical problems for hosting a 30-person crew and a 6-person cast, becoming "a weird fusion between sci-fi and the guerrilla-style approach to filmmaking".[25]

Mathematic accuracy

editThe Cube was conceived by mathematician David W. Pravica, who was the math consultant.[26] It consists of an outer cubical shell or sarcophagus, and the inner cube rooms. Each side of the outer shell is 434 feet (132 m) long. The inner cube consists of 263 = 17,576 cubical rooms (minus an unknown number of rooms to allow for movement), each having a side length of 15.5 feet (4.7 m). A space of 15.5 feet (4.7 m) is between the inner cube and the outer shell. Each room is labelled with three identification numbers such as "517 478 565". These numbers encode the starting coordinates of the room, and the X, Y, and Z coordinates are the sums of the digits of the first, second, and third number, respectively. The numbers also determine the movement of the room. The subsequent positions are obtained by cyclically subtracting the digits from one another, and the resulting numbers are then successively added to the starting numbers.[27]

Post-production

editDuring post-production, Natali spent months "on the aural environment", including appropriate sound effects of each room, so the Cube could feel like what he described as a haunted house.[20]

Release

editCube was shown at the Toronto International Film Festival on 9 September 1997[1] and released in Ottawa and Montreal on 18 September 1998.[1] A theatrical release occurred in Spain in early 1999,[19] while in Italy a release was scheduled for July 1999[28] and an opening in Germany was set for later that year.[15] In the Japanese market, it became the top video rental at the time,[29] and exceeded expectations, with co-writer Graeme Manson suggesting people in Japan had a better understanding of living in boxes so resonated better with the Japanese audience, as they were likely "more receptive to the whole metaphor underlying the film".[19]

The film's television debut in the United States was on 24 July 1999 on the Sci-Fi channel.[25]

In 2023, the film was one of 23 titles that were digitally restored under its new Canadian Cinema Reignited program to preserve classic Canadian films.[30]

A 4K restoration of the film debuted at the 28th Fantasia International Film Festival on July 30, 2024.[31]

Reception

editBox office

editIn its home country of Canada, the film was a commercial failure, lasting only a few days in Canadian theatres. French film distributor Samuel Hadida's company Metropolitan Filmexport saw potential in the film and spent $1.2 million in a marketing campaign, posting flyers in many cities and flying members of the cast over to France to meet moviegoers. At its peak, the film was shown at 220 French box offices and became among the most popular films in France of that time, collecting over $10 million in box office receipts.[28] It went on to be the second-highest-grossing film in France that summer.[15]

Elsewhere internationally, the film grossed $501,818 in the United States,[7] and $8,479,845 in other territories, for a worldwide total of $8,981,663.[6]

Critical response

editOn review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, Cube holds an approval rating of 63%, based on 40 reviews, and an average rating of 6.3/10. The website's consensus reads: "Cube sometimes struggles with where to take its intriguing premise, but gripping pace and an impressive intelligence make it hard to turn away".[32] On Metacritic, the film has a score 61 out of 100, based on 12 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[33]

Bob Graham of the San Francisco Chronicle was highly critical: "If writer-director Vincenzo Natali, storyboard artist for Keanu Reeves's Johnny Mnemonic, were as comfortable with dialogue and dramatizing characters as he is with images, this first feature of his might have worked better".[34] Nick Schager from Slant Magazine rated the film three out of five stars, noting that, its intriguing premise and initially chilling mood were undone by threadbare characterizations, and lack of a satisfying explanation for the cube's existence. He concluded the film "winds up going nowhere fast".[35]

Anita Gates of The New York Times was more positive, saying the story "proves surprisingly gripping, in the best Twilight Zone tradition. The ensemble cast does an outstanding job on the cinematic equivalent of a bare stage... Everyone has his or her own theory about who is behind this peculiar imprisonment... The weakness in Cube is the dialogue, which sometimes turns remarkably trite... The strength is the film's understated but real tension. Vincenzo Natali, the film's fledgling director and co-writer, has delivered an allegory, too, about futility, about the necessity and certain betrayal of trust, about human beings who do not for a second have the luxury of doing nothing".[8] Bloody Disgusting gave a positive review: "Shoddy acting and a semi-weak script can't hold this movie back. It's simply too good a premise and too well-directed to let minor hindrances derail its creepy premise".[36] Kim Newman from Empire Online gave the film 4/5 stars, writing: "Too many low-budget sci-fi films try for epic scope and fail; this one concentrates on making the best of what it's got and does it well".[37]

Accolades

editThe film won the award for Best Canadian First Feature Film at the 1997 Toronto International Film Festival[14] and the Jury Award at the Brussels International Festival of Fantasy Film.[38]

In 2001, an industry poll conducted by Playback named it the eighth best Canadian film of the preceding 15 years.[39]

Series and remakes

editAfter Cube achieved cult status, it was followed by a sequel, Cube 2: Hypercube, released in 2002,[40] and a prequel, Cube Zero, released in 2004.[41]

In April 2015, The Hollywood Reporter wrote that Lionsgate Films was planning to remake the film, titled Cubed, with Saman Kesh directing, Roy Lee and Jon Spaihts producing, and a screenplay by Philip Gawthorne, based on Kesh’s original take.[42][43]

A Japanese remake, also called Cube, was released in October 2021.[44]

See also

edit- "The Library of Babel"

- List of films about mathematicians

- Saw (2004 film)

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g "Cube". Collections Canada. 12 May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- ^ Eisner, Ken (20 October 1997). "Cube". Variety. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Cube (1997)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "CUBE (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 7 July 1998. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Kornits, Dov (8 May 1999). "eFilmCritic – Director, Vincenzo Natali – Cube". eFilmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Cube (1998) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Cube (1998) – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b Gates, Anita (11 September 1998). "Cube (1997) FILM REVIEW; No Maps, Compasses Or Faith". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ "The Canadian Film Centre :: Our Projects". cfccreates.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b "A deadly puzzle". The Record. 11 September 1998. p. 133. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Singh, Jasneet (25 February 2024). "This Underrated Horror Film Paved the Way for Escape Room Movies". Collider. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ "Canadian Films Future". Toronto Star. 9 September 1997. ProQuest 437743703. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2022 – via ProQuest.

- ^ a b "Director found creative freedom in a 14-foot cube". The Record. 14 September 1998. p. 58. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Director escapes own maze". The Ottawa Citizen. 8 October 1998. p. 50. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Cubs director feels like a lucky geek". Times Colonist. 5 September 1999. p. 13. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ Berman, A.S. (2018). Cube: Inside the Making of a Cult Film Classic. BearManor Media. pp. 25–27, pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-1629332918.

- ^ "CBC.ca". CBC.ca. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Cube - Canada, 1997 - reviews". MOVIES & MANIA. 16 March 2019. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b c "Nearly a year after its lacklustre commercial release in North America, the Canadian film CUBE is making headlines in Europe". The Vancouver Sun. 15 July 1999. p. 34. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Boxed geeks". Sydney Morning Herald. 26 February 1999. p. 46. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "What do you call an American movie with a brain? Canadian". Sydney Morning Herald. 4 March 1999. p. 14. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Nicole de Boer interview about Cube (1997)". 28 March 2021. Archived from the original on 26 July 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ Graham, Bob (20 November 1998). "'Cube's' Cogs Stuck in Its Pure Visuals". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 19 January 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Emmer, Michele; Manaresi, Mirella (2003). Mathematics, Art, Technology, and Cinema. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 172–180. ISBN 978-3-540-00601-5. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Award-winning 'Cube' makes U.S. TV debut on Sci-Fi channel". News-Press. 18 July 1999. p. 176. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Cube. 9 September 1997. Event occurs at 1:28:17.

- ^ Polster, Burkard; Ross, Marty (2012). "6 Escape from the Cube". Math Goes to the Movies. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4214-0484-4. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Canadian small film a huge hit in France". The Leader-Post. 5 July 1999. p. 23. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Vincenzo Natali is feeling the love". National Post. 26 June 2002. p. 20. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Pat Mullen, "Oscar Winning Doc Leads List of Restored Canadian Classics". Point of View, May 9, 2023.

- ^ "Cube". Fantasia International Film Festival. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ "Cube (1998) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Cube Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Graham, Bob (20 November 1998). "'Cube's' Cogs Stuck in Its Pure Visuals - SFGate". SFGate.com. Bob Graham. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Schager, Nick (12 April 2003). "DVD Review: Cube - Slant Magazine". Slant Magazine.com. Nick Schager. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Bloody Disgusting Staff (22 October 2004). "Cube". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Newman, Kim (1 January 2000). "Cube Review". Empire Online.com. Kim Newman. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ "Cube (1997)". Canadian Film Centre. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Michael Posner, "Egoyan tops film poll". The Globe and Mail, November 25, 2001.

- ^ Hal Erickson (2013). "Cube 2: Hypercube". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ^ Jason Buchanan (2013). "Cube Zero". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ^ Kit, Borys (30 April 2015). "Lionsgate to Remake Cult Sci-Fi Hit 'Cube'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ Lesnick, Silas (30 April 2015). "Lionsgate Plans Cube Remake, Cubed". Comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (1 February 2021). "Shochiku Confirms 'Cube' Remake in Japan". Variety. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

External links

edit- ‹The template AllMovie title is being considered for deletion.› Cube at AllMovie

- Cube at IMDb

- Cube at Metacritic

- Cube at Rotten Tomatoes

- Cube at the TCM Movie Database