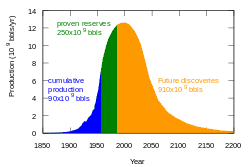

According to Hubbert peak theory, peak oil is the date when the peak of the world's conventional petroleum (crude oil) production rate is reached. After this date the rate of production is predicted to enter terminal decline, following the bell-shaped curve predicted by the theory. Some observers such as Kenneth S. Deffeyes, Matthew Simmons, and James Howard Kunstler believe that because of the high dependence of most modern industrial transport systems on inexpensive oil, the impending post-peak production decline and possible resulting severe price increases will herald negative implications for the future outlook of the global economy.

M. King Hubbert, who devised the theory, predicted in 1974 that peak oil would occur in 1995 at 12-GB/yr "if current trends continue".[1]

Because of world population growth, oil production per capita peaked in 1979 (with a plateau 1973-1979).[2]

Supply edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Oil is a finite, non-renewable resource.

The rate of oil 'production,' meaning extraction and refining (currently about 84 million barrels/day), has grown in most years over the last century, but once we go through the halfway point of all reserves, production becomes ever more likely to decline, hence 'peak'. Peak Oil means not 'running out of oil', but 'running out of cheap oil'.

About 70% of the world’s petroleum comes from only 370 giant fields, dubbed "elephants" because they are so huge. In part because of their size, the elephants were easy to find and inexpensive to produce. The discovery rate for elephants peaked in the 1960s. It’s getting more and more difficult to find new ones, even with new technology.[3]

Reserves edit

The Mideast remains the largest oil-producing region.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Exploration edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Demand edit

The U.S. Department of Energy categorizes national energy use in four broad sectors: transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial.[4] In the United States, in contrast to other regions of the world, about 2/3 of all oil use is for transportation, 1/5 goes to industrial uses, and the remainder goes to residential, commercial and electric energy production.[5]

Transportation edit

Because most oil is consumed in transportation, approximately 66.6% in the United States[6] and 55% worldwide,[7] much of the discussion regarding mitigation of the effects of oil depletion center around the development of transportation that uses less oil.

There are many forms of transportation that do not require oil or require much less than the standard automobile. Today, these include the application of public transport, biofuels, high mpg hybrid vehicles, bicycles, diesel vehicles,[8] battery electric vehicles, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Hydrogen vehicles[9] such as General Motors Sequel are also being developed, although hydrogen fuel would need to be sourced from hydrocarbons (oil) or water (requiring a greater energy input than that generated by combusting the resulting hydrogen). Because America uses 1 out of every 4 barrels of global oil consumed[10][11] and uses 66.6% for transportation, it uses roughly 17% of global oil consumption for transportation and is potentially the largest market for any new type of vehicle. However less than 30% of personal auto expenditures in 2003 were on gasoline and oil as compared with over 40% in 1980[12] and personal use is just one component of overall transportation.

More comprehensive mitigations include better land use planning through smart growth to reduce transportation inducements, increased capacity and use of mass transit, vanpooling and carpooling,[13] bus rapid transit, telecommuting, and human-powered transport from current levels.[14] Rationing and driving bans are also forms of mitigation.[13] In order to deal with potential problems from peak oil, Colin Campbell has proposed the Rimini protocol.

Population edit

Population growth is causing an increase in oil demand.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Industrialization edit

Nations industrializing causes an increase in oil demand.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Implications of an unmitigated world peak edit

According to the Hirsch report prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy in 2005, a global decline in oil production would have serious social and economic implications without due preparation. Initially, an unmitigated peak in oil production would manifest itself as rapidly escalating prices and a worldwide energy crisis. While past oil shortages stemmed from a temporary insufficiency of supply, crossing Hubbert's Peak means that the production of oil continues to decline, so demand must be reduced to meet supply. If alternatives or conservation (orderly demand destruction) are not forthcoming, then disorderly demand destruction will occur, with the possible effect that the many products and services produced with oil become scarcer, leading to lower living standards.

- Air travel, using roughly 7% of world oil consumption,[15] would be one of the affected services. The energy density of hydrocarbons and the power density of a jet engine are so necessary for aviation that hydrocarbon fuels are nearly impossible to replace with electricity, to an extent beyond any other common mode of transport.

- A US Army Corps of Engineers report[16] on the military's energy options states

The Army and the nation’s heavy use of oil and natural gas is not well coordinated with either the nation’s or the Earth’s resources and upcoming availability.

- Shipping costs[17]

On average, a one percent increase in fuel prices leads to a 0.4% increase in total freight rates. Using this rule of thumb, the recent doubling in oil prices has raised averaged freight rates by almost 40%.

Shipping costs are particularly relevant to a country like Japan that has greater food miles.[18]

- Increasing cost of oil for importing countries ultimately reduces those countries' purchase of non-oil goods abroad. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco discusses oil and the US balance of trade:[19]

Oil prices have almost quadrupled since the beginning of 2002. For an oil-importing country like the U.S., this has substantially increased the cost of petroleum imports. International trade data suggest that this increase has exacerbated the deterioration of the U.S. trade deficit, especially since the second half of 2004.

US indications of economic volatility have manifested themselves in the largest increase in inflation rates in 15 years (Sept. 2005), due mostly to higher energy costs.[20]

- Significant oil producing countries will have a national purchasing advantage over similar countries with no oil to sell. This can result in larger militaries for oil producers or inflation of the price of whatever commodities they purchase.[21] Saudi Arabia purchased US$40 billion worth of arms from the US between 1990 and 2000.[22]

- The United States averaged 464 gallons of gas per person in 2004.[23] Therefore, increased gasoline cost will make gas reducing alternatives popular for lower income US residents.

Oil industry analyst Jan Lundberg proposes a dark scenario called petrocollapse.[24] Contrasting views note that most uses of oil, from plastics to transportation fuels, have substitutes.[25]

Mitigation edit

The effects of peak oil can be mitigated through conservation and finding alternatives.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Conservation edit

Oil can be conserved in a number of ways.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Alternatives to conventional oil edit

Of the currently available alternatives to oil, the most viable ones are:

- renewable energy sources (solar, wind, hydro, tidal, geothermal, wave, ocean thermal)

- ethanol fuel

- butanol fuel

- biodiesel

- tar sands

- oil shale

- coal liquefaction

- gasification

- nuclear energy (fission or fusion)

One near-term alternative source of liquid fuel is the Athabasca Tar Sands in Alberta, Canada. Production from this source is around 1 mbbl/day as of 2006, and is expected to build up to 3.2 mbbl/day by 2015. New technology has drastically reduced the cost of extracting oil from this source. The current extraction process, however, requires large inputs of natural gas and fresh water.[26] The figure for recoverable reserves from this source was around 180 billion barrels as of mid-2005[27] (cf. the Saudi Arabian reserve of about 260 billion barrels of conventional oil). A similar field, the Orinoco tar sands in Venezuela, is also being exploited. These two are the largest known fields of tar (i.e., bitumen) sands.

Even in 2005, before further dramatic techological improvements in the ease of extraction, the potential of oil shale in the US is discussed by a RAND study:[28]

Under high growth assumptions, an oil shale production level of 1 million barrels per day is probably more than 20 years in the future, and 3 million barrels per day is probably more than 30 years into the future.

Synthetic fuel, created via coal liquefaction, requires no engine modifications for use in standard automobiles. As a byproduct of oil embargoes during Apartheid in South Africa, Sasol, using the Fischer-Tropsch process, developed relatively low-cost coal-based fuel. Currently, about 30% of South Africa's transport-fuel (mostly diesel) is produced from coal.[29] With crude-oil prices above US$40 per barrel, this process is now cost-effective.

Current events edit

Peak oil production—has it happened already? edit

Matthew Simmons, Chairman of Simmons & Company International, said on October 26, 2006 that global oil production may have peaked in December 2005, though he cautions that further monitoring of production is required to determine if a peak has actually occurred.[31]

In State of the World 2005, Worldwatch Institute observes that oil production is in decline in 33 of the 48 largest oil producing countries.[32] Other countries have also passed their individual oil production peaks.

World oil production growth trends, in the short term, have been flat over the last 18 months. Global production averaged 85.24 mbbl/d in 2006, up 0.76 mbbl/d (0.9%), from 84.48 mbbl/d in 2005.[33] Production in Q4 2006 was 85.38 mbbl/d, up 1.09 mbbl/d (1.3%), from the same period a year earlier. Average yearly gains in world oil production from 1987 to 2005 were 1.2 mbbl/d (1.7%), with yearly gains since 1997 ranging from -1.4 mbbl/d, (-1.9%; 1998–1999) to 3.3 mbbl/d (4.1%; 2003–2004).[33]

Of the largest 21 fields, about 9 are already in decline.[34]

Mexico announced that its giant Cantarell Field entered depletion in March, 2006,[35] as did the huge Burgan field in Kuwait in November, 2005.[36] Due to past overproduction, Cantarell is now declining rapidly, at a rate of 13% per year.[37] In April, 2006, a Saudi Aramco spokesman admitted that its mature fields are now declining at a rate of 8% per year, and its composite decline rate of producing fields is about 2%,[38] thus implying that Ghawar, the largest oil field in the world, has peaked.[39]

Many commentators have pointed to the Jack 2 deep water test well in the Gulf of Mexico, announced September 5, 2006[40], as evidence that there is no imminent peak in global oil production. The Jack 2 field may have the potential to provide nearly 2 years of U.S. consumption at present levels. Peak oil theory, however, does not suggest that there will be no major oil finds in the future, but rather that new discoveries and new production will not be able to offset depletion in other parts of the world.[41]

Increasing investment in harder to reach oil is a sign of oil companies' belief in the end of easy oil:[42]

All the easy oil and gas in the world has pretty much been found," said William J. Cummings, ExxonMobil's spokesman in Angola. "Now comes the harder work in finding and producing oil from more challenging environments and work areas.

The "harder work" mentioned has, however, already displayed the potential to unlocking crude oil measured in the trillions of barrels. Chuck Masters of the USGS says:

Unconventional resources, such as extra heavy oils, tar sands, gas in tight sands, and coal bed methane are not considered [in the USGS 2000 assessment] but they must, nonetheless, be recognized as being present in very large quantities. ... The two major sources of unconventional oil ... are the extra heavy oil in the Orinoco province of Venezuela and the ... tar sands in the Western Canada Basin. Taken together, these resource occurrences, in the Western Hemisphere, are approximately equal to the Identified Reserves of conventional crude oil accredited to the Middle East.

This "harder work" has failed, however, to either significantly increase the actual production of oil globally, or to significantly reduce the price of oil. This paradox—between theories of how to extract untold trillions of barrels of oil with stagnant actual oil production—highlights the core of peak oil theory: peak oil does not mean that we will run out of oil, or even that we will cease to make major oil discoveries, but rather that we will be unable to maintain current levels of oil production.

Oil price edit

In 2004, 30 billion barrels of oil were consumed worldwide, while eight billion barrels of new oil reserves were discovered in new accumlations, a number which excludes reserve growth in existing fields. In August 2005, the International Energy Agency reported global demand at 84.9 million barrels per day, resulting in an annual demand of over 31 billion barrels.[43] This means consumption is now within 2 Mbbl/d of production. At any one time there are about 54 days of stock in the OECD system plus 37 days in emergency stockpiles. In June 2005, OPEC admitted that they would 'struggle' to pump enough oil to meet pricing pressures for the fourth quarter of that year.[citation needed] The summer and winter of 2005 brought oil prices to a new high (not adjusted for inflation). On the other hand, some analysts attribute much of this new high to disruptions caused by the war in Iraq.[44]

An oil price chart can be seen here.

Market economy versus government edit

Part of the current debate revolves around energy policy, and whether to shift funding to increasing energy conservation, fuel efficiency, or other energy sources like solar, wind, and nuclear power. For example, in the USA Rep. Tom Udall at congressional peak oil hearings:[45]

Some say that market forces will take care of the peak oil problem. They argue that as we approach or pass the peak of production, the price of oil will increase and alternatives will become more competitive. Following this, consumers will act to replace our need for non-petroleum energy resources. This philosophy is partly true. However, the main problem with this argument is that current U.S. oil prices do not accurately reflect the full social costs of oil consumption. Currently, in the United States, federal and state taxes add up to about 40 cents per gallon of gasoline. A World Resources Institute analysis found that fuel-related costs not covered by drivers are at least twice that much. The current price of oil does not include the full cost of road maintenance, health and environmental costs attributed to air pollution, the financial risks of global warming from increasing carbon dioxide emissions or the threats to national security from importing oil. Because the price of oil is artificially low, significant private investment in alternative technologies that provide a long-term payback does not exist. Until oil and its alternatives compete in a fair market, new technologies will not thrive.

For the United States investments like FreedomCAR, Hydrogen Fuel Initiative[46] and a DOE loan guarantee program[47] are driven by Hubbert peak theory applied to US peak production as well as global peak predictions. In China[48] and Japan[49] lack of native oil resources may also overshadow the world peak. In Europe initiatives such as Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation are marketed more in terms of the environment.

The Congressional Budget Office provides debate of government research versus incentives:[50]

... the federal government could more effectively increase the efficiency of the nation's automotive fleet by raising gasoline taxes, imposing user fees on the purchase of low-mileage-per-gallon vehicles, or both. ...Such policies might also spur more-productive research--because automakers would have a greater incentive not only to conduct research into fuel-cell technology but also to broaden their research efforts to include other potential sources of fuel efficiency, such as more-sophisticated drive trains and transmissions and lightweight but durable chassis and body materials.

A warning of the level of incentive required for market driven research and development is stated by Rogner:[51]

Additionally, production cost reductions will not materialize in the absence of investments. Their magnitude and timing may affect the timing of future access to hydrocarbon resources. The scale of upfront investment requirements is expected to increase while the economic risk associated with upstream hydrocarbon projects will likely be higher than for alternative non-energy investment opportunities (61). Therefore, the quest for short-term profits may well be a road block to long-term resource development.

The problems of privately funded research and development, especially that funded by venture capital, are not unique to peak oil mitigation.[52]

even if problems associated with incomplete appropriability of the returns to R&D are solved using intellectual property protection, subsidies, or tax incentives, it may still be difficult or costly to finance R&D using capital from sources external to the firm or entrepreneur. That is, there is often a wedge, sometimes large, between the rate of return required by an entrepreneur investing his own funds and that required by external investors.

The severity of the problem for energy is echoed in the International Energy Agency's latest report[53]

In the US, transportation by car is guided more by the government than by an invisible hand. Roads and the interstate highway system were built by local, state and federal governments and paid for by income taxes, property taxes, fuel taxes, and tolls. The Strategic Petroleum Reserve is designed to offset market imbalances. Municipal parking is frequently subsidized.[54] Emission standards regulate pollution by cars. US fuel economy standards exist but are not high enough to have effect. There is also a gas guzzler tax of limited scope. The United States offers tax credits for certain vehicles and these frequently are hybrids or compressed natural gas cars, see Energy Policy Act of 2005.

In order to be profitable, many alternatives to oil require the price of oil to remain above some level. So investors in these alternatives must gamble with the limited data on oil reserves available. This imperfect information can lead to a market failure caused by a move by nature; for instance see Hotelling's rule for non-renewable resources. Even with perfect information the price of oil correlates with spare capacity and spare capacity does not warn of a peak:[55]

To put this into perspective, in 2004 world oil production is 80 Mb/d; spare capacity would need to be 44 Mb/d to be equivalent to US conditions in 1962. To predict that US production would peak in less than ten years given this much spare capacity seemed at the very least completely unrealistic to most people.

This problem might be solved by the government establishing a price floor for oil.[citation needed] A tax shift raising gas taxes is the same idea.[56] Opponents of a price floor for oil argue that the markets would distrust the government's ability to keep the policy when oil prices are low.[57]

Oil production per capita edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2010) |

Because of world population growth, oil production per capita peaked in the 1970s.[2] It is expected that worldwide oil production in the year 2030 will be the same as it was in 1980. The world’s population in 2030 is expected to double from 1980 and much more industrialized and oil-dependent than it was in 1980. Consequently, worldwide demand for oil will significantly outpace worldwide production of oil.[58]

Some physicists maintain that the non-sustainability of oil production per capita was not addressed due political correctness implications of suggesting population control.[59] Others say the peaking wasn't noticed due to global socioeconomic inequality. [citation needed]

See also edit

Prediction edit

Economics edit |

Technology edit

Others edit

|

References edit

- ^ Noel Grove, reporting M. King Hubbert (June 1974). "Oil, the Dwindling Treasure". National Geographic.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lay-source=and|lay-date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Duncan, Richard C. (November 2001). "The Peak of World Oil Production and the Road to the Olduvai Gorge". Population & Environment. 22 (5): 503–522. doi:10.1023/A:1010793021451. ISSN (Print) 1573-7810 (Online) 0199-0039 (Print) 1573-7810 (Online).

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lay-source=and|lay-date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Randy Udall (1999). "When Will the Joy Ride End?".

- ^ "Annual Energy Report" (PDF). US Dept. of Energy. July 2006.

- ^ "Global Oil Consumption". Energy Information Administration.

- ^ "Domestic Demand for Refined Petroleum Products by Sector". Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

- ^ Hirsch report

- ^ "Honda announces cleaner, "greener" diesel power train for automobiles".

- ^ "California Hydrogen Highway".

- ^ "World Oil Consumption by Region, Reference Case, 1990-2030" (PDF). United States Department of Energy.

- ^ "OECD1 Countries and World Petroleum (Oil) Demand, 1997-present" (XLS). United States Department of Energy.

- ^ "National Transportation Statistics - Automobile Profile". Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

broken link

- ^ a b "Saving Oil Executive Summary" (PDF). International Energy Agency.

- ^ "Principal Means of Transportation to Work". Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

- ^ "How many air-miles are left in the world's fuel tank?".

- ^ Donald F. Fournier and Eileen T. Westervelt (September 2005). "Energy Trends and Their Implications for U.S. Army Installations" (PDF).

- ^ Jeff Rubin and Benjamin Tal (2005-10-19). "Soaring Oil Prices Will Make The World Rounder" (PDF). CIBC World Markets.

- ^ "Peak Oil and Japan's Food Dependence".

- ^ "FRBSF Economic Letter 2006-24 'Oil Prices and the U.S. Trade Deficit'". Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. 2006-09-22.

- ^ Jeffrey Bogen. "Import price rise in 2005 due to continued high energy prices" (PDF). US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- ^ "Brad Setser's Web Log".

- ^ "Saudia Arabia". Federation of American Scientists.

- ^ "U.S. Gasoline Per Capita Use by State 2004". California Energy Commission.

- ^ "petrocollapse".

- ^ "Energy Future Coalition Report of the Bioenergy and Agriculture Working Group" (PDF). biotechnology Industry Organization. 2003-06-18.

- ^ "About Tar Sands". Oil Shale and Tar Sands Leasing Programmatic EIS.

- ^ Thomas J. Quinn (16 July 2005). "Turning tar sands into oil".

- ^ James T. Bartis, Tom LaTourrette, Lloyd Dixon, D.J. Peterson, Gary Cecchine (2005). "Oil Shale Development in the United States" (PDF). RAND.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Patrick Barta (2006-08-17). "South Africa has a way to make oil from coal". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ http://omrpublic.iea.org/world/wb wosup.pdf

- ^ "Peak oil - October 28". 2006-10-28.

- ^ WorldWatch Institute (2005-01-01). State of the World 2005: Redefining Global Security. New York: Norton. p. 107. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/ISBN 0-393-32666-7|[[ISBN 0-393-32666-7]]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ a b "World Oil Supply and Demand" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2007-01-18.

- ^ "Peak Oil and Energy Resources".

- ^ "Canales: Output will drop at Cantarell field". El Universal. 2006-02-10.

- ^ James Cordahi and Andy Critchlow (2005-11-09). "Kuwait Oil Field, World's Second Largest, 'Exhausted'". Bloomberg.

- ^ Adriana Arai (2006-08-01). "Mexico's Largest Oil Field Output Falls to 4-Year Low". Bloomberg.

- ^ Ryan McGreal (2006-04-29). "Peak Oil for Saudi Arabia?". Raise the Hammer.

- ^ Matthew S. Miller (2007-03-09). "Ghawar Is Dead!". Energy Bulletin.

- ^ "Chevron Announces Record Setting Well Test at Jack". Chevron. 2006-09-05.

- ^ Greg Geyer (2006-09-19). "Jack-2 Test Well Behind The Hype". Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas.

- ^ "Price rise and new deep-water technology opened up offshore drilling". The Boston Globe. 2005-12-11.

- ^ "Oil Market Report - Demand" (PDF). International Energy Association.

- ^ Richard M. Ebeling (2003-03-05). "Why War with Iraq? Follow the Money". The Future of Freedom Foundation.

- ^ "Peak Oil Hearing: Udall Testimony". United States House of Representatives. 2005-12-07.

- ^ "President's Hydrogen Fuel Initiative".

- ^ "DOE Proposes Regulations for Loan Guarantee Program". DOE. 2007-05-17.

- ^ "Bright prospects of China's green car industry". People's Daily Online. July 11, 2006.

- ^ "New Battery Technology Set to Change Vehicles in the Near Future" (PDF). New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). 2005.

- ^ "Energy". Congressional Budget Office. February 2005.

- ^ Hans-Holger Rogner (November 1997). "An Assessment of World Hydrocarbon Resources" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 22: 217–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.22.1.217.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lay-source=and|lay-date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "The Financing of Research and Development" (PDF). Oxford Rev. Econ. Pol. 18 (1). 2002.

NBER Working Paper No. 8773 (February 2002); University of California at Berkeley Dept. of Economics Working Paper No. E02-311 (January 2002)

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lay-source=and|lay-date=(help); Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - ^ "WEO 2006 identifies under-investment in new energy supply as a real risk". International Energy Agency. 2006-11-07.

- ^ Keith Bawolek (March 2004). "What Drives Parking Investments?". CIRE Magazine.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^

Alfred J. Cavallo (December 2004). "Hubbert's Petroleum Production Model: An Evaluation and Implications for World Oil Production Forecasts" (PDF). Natural Resources Research. 13 (4).

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|lay-source=and|lay-date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Lester R. Brown (2006-05-11). "Let's Raise Gas Taxes and Lower Income Taxes". Earth Policy Institute.

- ^ Jerry Taylor and Peter Van Doren (2006-06-01). "An Argument against Oil Price Minimums". Cato Institute.

- ^ "Are We 'Running Out'? I Thought There Was 40 Years of the Stuff Left".

- ^ Albert A. Bartlett (2004-08-27). "Thoughts on Long-Term Energy Supplies: Scientists and the Silent Lie" (PDF). Physics Today.