Doxycycline is a broad-spectrum antibiotic of the tetracycline class used in the treatment of infections caused by bacteria and certain parasites.[1] It is used to treat bacterial pneumonia, acne, chlamydia infections, Lyme disease, cholera, typhus, and syphilis.[1] It is also used to prevent malaria.[2][3] Doxycycline may be taken by mouth or by injection into a vein.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌdɒksɪˈsaɪkliːn/ DOKS-iss-EYE-kleen |

| Trade names | Doxy, Doryx, Vibramycin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682063 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100% |

| Protein binding | 80–90% |

| Metabolism | Negligible |

| Elimination half-life | 10–22 hours |

| Excretion | Mainly feces, 40% urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.429 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

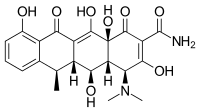

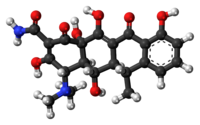

| Formula | C22H24N2O8 |

| Molar mass | 444.440 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and an increased risk of sunburn.[1] Use during pregnancy is not recommended.[1] Like other agents of the tetracycline class, it either slows or kills bacteria by inhibiting protein production.[1][4] It kills malaria by targeting a plastid organelle, the apicoplast.[5][6]

Doxycycline was patented in 1957 and came into commercial use in 1967.[7][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[9] Doxycycline is available as a generic medicine.[1][10] In 2022, it was the 68th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 9 million prescriptions.[11][12]

Medical uses

editIn addition to the general indications for all members of the tetracycline antibiotics group, doxycycline is frequently used to treat Lyme disease, chronic prostatitis, sinusitis, pelvic inflammatory disease,[13][14] severe acne, rosacea,[15][16][17] and rickettsial infections.[18] The efficiency of oral doxycycline for treating papulopustular rosacea and adult acne is not solely based on its antibiotic properties, but also on its anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic properties.[19]

In Canada, in 2004, doxycycline was considered a first-line treatment for chlamydia and non-gonococcal urethritis and with cefixime for uncomplicated gonorrhea.[20]

Antibacterial

editGeneral indications

editDoxycycline is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that is employed in the treatment of numerous bacterial infections. It is effective against bacteria such as Moraxella catarrhalis, Brucella melitensis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Additionally, doxycycline is used in the prevention and treatment of serious conditions like anthrax, leptospirosis, bubonic plague, and Lyme disease. However, some bacteria, including Haemophilus spp., Mycoplasma hominis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, have shown resistance to doxycycline.[21][22] It is also effective against Yersinia pestis (the infectious agent of bubonic plague), and is prescribed for the treatment of Lyme disease,[23][24][25][26] ehrlichiosis,[27][28] and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.[29]

Specifically, doxycycline is indicated for treatment of the following diseases:[29][30]

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever, typhus fever and the typhus group, scrub typhus,[31] Q fever,[32] rickettsialpox, and tick fevers caused by Rickettsia,[33][34][35]

- respiratory tract infections caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae,[36]

- Lymphogranuloma venereum, trachoma, inclusion conjunctivitis, and uncomplicated urethral, endocervical, or rectal infections in adults caused by Chlamydia trachomatis,[29][30]

- psittacosis,[29][30]

- non-gonococcal urethritis caused by Ureaplasma urealyticum,[29][30]

- relapsing fever due to Borrelia recurrentis,[29][30]

- chancroid caused by Haemophilus ducreyi,[29][30]

- plague due to Yersinia pestis,[29][30]

- tularemia,[29][30]

- cholera,[29][30]

- campylobacter fetus infections,[29][30]

- brucellosis caused by Brucella species (in conjunction with streptomycin),[29][30]

- bartonellosis,[29][30]

- granuloma inguinale (Klebsiella species),[29][30]

- Lyme disease:[37] it can be used in adults and children. For treatment or prophylaxis of Lyme disease in children, it can be used for a duration of up to 21 days in children of any age.[38] Doxycycline is specifically indicated to treat Lyme disease for patients presenting with erythema migrans. As for the optimal duration of treatment of this disease, guidelines vary, with some recommending a 10-day course of doxycycline, while others suggest a 14-day course; still, recent data suggest that even a 7-day course of doxycycline can be effective. Compared to other drugs, there are no significant differences in treatment response across antibiotic agents, doses, or durations when comparing 14 days versus 21 days; as such, the optimal duration of treatment of Lyme disease remains uncertain, as prolonged antibiotic courses have drawbacks, including diminishing returns in terms of patient outcomes, heightened risks of adverse events, superinfections, increased healthcare costs, and the potential for development of antibiotic resistance. Therefore, the consensus remains to treat patients with the shortest effective duration of antibiotics, as is the case with doxycycline for Lyme disease as well.[39]

Gram-negative bacteria specific indications

editWhen bacteriologic testing indicates appropriate susceptibility to the drug, doxycycline may be used to treat these infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria:[29][30]

- Escherichia coli infections,[29][30]

- Enterobacter aerogenes (formerly Aerobacter aerogenes) infections,[29][30]

- Shigella species infections,[29][30]

- Acinetobacter species (formerly Mima species and Herellea species) infections,[29][30]

- respiratory tract infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae,[29][30]

- respiratory tract and urinary tract infections caused by Klebsiella species.[29][30]

Gram-positive bacteria specific indications

editSome Gram-positive bacteria have developed resistance to doxycycline. Up to 44% of Streptococcus pyogenes and up to 74% of S. faecalis specimens have developed resistance to the tetracycline group of antibiotics. Up to 57% of P. acnes strains developed resistance to doxycycline.[40] When bacteriologic testing indicates appropriate susceptibility to the drug, doxycycline may be used to treat these infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria:[29][30]

- upper respiratory infections caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (formerly Diplococcus pneumoniae),[29][30]

- skin and soft tissue infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections,[29][30]

- anthrax caused by Bacillus anthracis infection.[29][30]

Specific applications of doxycycline when penicillin is contraindicated

editWhen penicillin is contraindicated, doxycycline can be used to treat:[29][30]

- syphilis caused by Treponema pallidum,[29][30]

- yaws caused by Treponema pertenue,[29][30]

- listeriosis due to Listeria monocytogenes,[29][30]

- Vincent's infection caused by Fusobacterium fusiforme,[29][30]

- actinomycosis caused by Actinomyces israelii,[29][30]

- infections caused by Clostridium species.[29][30]

Use as adjunctive therapy

editDoxycycline may also be used as adjunctive therapy for severe acne.[41][29][30]

Subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline (SDD) is widely used as an adjunctive treatment to scaling and root planing for periodontitis. Significant differences were observed for all investigated clinical parameters of periodontitis in favor of the scaling and root planing + SDD group where SDD dosage regimens is 20 mg twice daily for three months in a meta-analysis published in 2011.[42] SDD is also used to treat skin conditions such as acne and rosacea,[15][43][44] including ocular rosacea.[45] In ocular rosacea, treatment period is 2 to 3 months. After discontinuation of doxycycline, recurrences may occur within three months; therefore, many studies recommend either slow tapering or treatment with a lower dose over a longer period of time.[45]

Doxycycline is used as an adjunctive therapy for acute intestinal amebiasis.[46]

Doxycycline is also used as an adjunctive therapy for chancroid.[46]

As prophylaxis against sexually transmitted infections

editDoxycycline is used for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted bacterial infections (STIs), but it has been associated with tetracycline resistance in associated species, in particular, in Neisseria gonorrhoeae.[47][48][49] For this reason, the Australian consensus statement mentions that doxycycline for PEP particularly in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) should be considered only for the prevention of syphilis in GBMSM, and that the risk of increasing antimicrobial resistance outweighed any potential benefit from reductions in other bacterial STIs in GBMSM.[50]

Appropriate use of doxycycline for PEP is supported by guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)[51] and the Australasian Society for HIV Medicine.[52][53]

Use in combination

editThe first-line treatment for brucellosis is a combination of doxycycline and streptomycin and the second-line is a combination of doxycycline and rifampicin (rifampin).[54]

Antimalarial

editDoxycycline is active against the erythrocytic stages of Plasmodium falciparum but not against the gametocytes of P. falciparum.[55] It is used to prevent malaria.[56] It is not recommended alone for initial treatment of malaria, even when the parasite is doxycycline-sensitive, because the antimalarial effect of doxycycline is delayed.[57]

Doxycycline blocks protein production in apicoplast (an organelle) of P. falciparum—such blocking leads to two main effects: it disrupts the parasite's ability to produce fatty acids, which are essential for its growth, and it impairs the production of heme, a cofactor. These effects occur late in the parasite's life cycle when it is in the blood stage, causing the symptoms of malaria.[58] By blocking important processes in the parasite, doxycycline both inhibits the growth and prevents the multiplication of P. falciparum. It does not directly kill the living organisms of P. falciparum but creates conditions that prevent their growth and replication.[59]

The World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines state that the combination of doxycycline with either artesunate or quinine may be used for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria due to P. falciparum or following intravenous treatment of severe malaria.[60]

Antihelminthic

editDoxycycline kills the symbiotic Wolbachia bacteria in the reproductive tracts of parasitic filarial nematodes, making the nematodes sterile, and thus reducing transmission of diseases such as onchocerciasis and elephantiasis.[61] Field trials in 2005 showed an eight-week course of doxycycline almost eliminates the release of microfilariae.[62]

Spectrum of susceptibility

editDoxycycline has been used successfully to treat sexually transmitted, respiratory, and ophthalmic infections. Representative pathogenic genera include Chlamydia, Streptococcus, Ureaplasma, Mycoplasma, and others. The following represents minimum inhibitory concentration susceptibility data for a few medically significant microorganisms.[63]

- Chlamydia psittaci: 0.03 μg/mL[63]

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae: 0.016–2 μg/mL[63]

- Streptococcus pneumoniae: 0.06–32 μg/mL[63]

Sclerotherapy

editDoxycycline is also used for sclerotherapy in slow-flow vascular malformations, namely venous and lymphatic malformations, as well as post-operative lymphoceles.[64]

Off-label use

editDoxycycline has found off-label use in the treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR). Together with tauroursodeoxycholic acid, doxycyclin appears to be a promising combination capable of disrupting transthyretine TTR fibrils in existing amyloid deposits of ATTR patients.[65]

Routes of administration

editDoxycycline can be administered via oral or intravenous routes.[1]

The combination of doxycycline with dairy, antacids, calcium supplements, iron products, laxatives containing magnesium, or bile acid sequestrants is not inherently dangerous, but any of these foods and supplements may decrease absorption of doxycycline.[66][67]

Doxycycline has a high oral bioavailability, as it is almost completely absorbed in the stomach and proximal small intestine.[15] Unlike other tetracyclines, its absorption is not significantly affected by food or dairy intake.[15] However, co-administration of dairy products reduces the serum concentration of doxycycline by 20%.[15] Doxycycline absorption is also inhibited by divalent and trivalent cations, such as iron, bismuth, aluminum, calcium and magnesium.[15] Doxycycline forms unstable complexes with metal ions in the acidic gastric environment, which dissociate in the small intestine, allowing the drug to be absorbed. However, some doxycycline remains complexed with metal ions in the duodenum, resulting in a slight decrease in absorption.[15]

Contraindications

editSevere liver disease or concomitant use of isotretinoin or other retinoids are contraindications, as both tetracyclines and retinoids can cause intracranial hypertension (increased pressure around the brain) in rare cases.[66]

Pregnancy and lactation

editDoxycycline is categorized by the FDA as a class D drug in pregnancy. Doxycycline crosses into breastmilk.[68] Other tetracycline antibiotics are contraindicated in pregnancy and up to eight years of age, due to the potential for disrupting bone and tooth development.[69] They include a class warning about staining of teeth and decreased development of dental enamel in children exposed to tetracyclines in utero, during breastfeeding or during young childhood.[70] However, the FDA has acknowledged that the actual risk of dental staining of primary teeth is undetermined for doxycycline specifically. The best available evidence indicates that doxycycline has little or no effect on hypoplasia of dental enamel or on staining of teeth and the CDC recommends the use of doxycycline for treatment of Q fever and also for tick-borne rickettsial diseases in young children and others advocate for its use in malaria.[71]

Adverse effects

editAdverse effects are similar to those of other members of the tetracycline antibiotic group. Doxycycline can cause gastrointestinal upset.[72][73] Oral doxycycline can cause pill esophagitis, particularly when it is swallowed without adequate fluid, or by persons with difficulty swallowing or impaired mobility.[74] Doxycycline is less likely than other antibiotic drugs to cause Clostridioides difficile colitis.[75]

An erythematous rash in sun-exposed parts of the body has been reported to occur in 7.3–21.2% of persons taking doxycycline for malaria prophylaxis. One study examined the tolerability of various malaria prophylactic regimens and found doxycycline did not cause a significantly higher percentage of all skin events (photosensitivity not specified) when compared with other antimalarials. The rash resolves upon discontinuation of the drug.[76]

Unlike some other members of the tetracycline group, it may be used in those with renal impairment.[77]

Doxycycline use has been associated with increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease.[78] In one large retrospective study, patients who were prescribed doxycycline for their acne had a 2.25-fold greater risk of developing Crohn's disease.[79]

Interactions

editPreviously, doxycycline was believed to impair the effectiveness of many types of hormonal contraception due to CYP450 induction. Research has shown no significant loss of effectiveness in oral contraceptives while using most tetracycline antibiotics (including doxycycline), although many physicians still recommend the use of barrier contraception for people taking the drug to prevent unwanted pregnancy.[80][77][81]

Pharmacology

editDoxycycline, like other tetracycline antibiotics, is bacteriostatic. It works by preventing bacteria from reproducing through the inhibition of protein synthesis.[82]

Doxycycline is highly lipophilic, so it can easily enter cells, meaning the drug is easily absorbed after oral administration and has a large volume of distribution. It can also be re-absorbed in the renal tubules and gastrointestinal tract due to its high lipophilicity, giving it a long elimination half-life, and it is also prevented from accumulating in the kidneys of patients with kidney failure due to the compensatory excretion in faeces.[73][83] Doxycycline–metal ion complexes are unstable at acid pH, therefore more doxycycline enters the duodenum for absorption than the earlier tetracycline compounds. In addition, food has less effect on absorption than on absorption of earlier drugs with doxycycline serum concentrations being reduced by about 20% by test meals compared with 50% for tetracycline.[84]

Mechanism of action

editDoxycycline is a broad-spectrum bacteriostatic antibiotic. It inhibits the synthesis of bacterial proteins by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit, which is only found in bacteria.[72][83] This prevents the binding of transfer RNA to messenger RNA at the ribosomal subunit meaning amino acids cannot be added to polypeptide chains and new proteins cannot be made. This stops bacterial growth giving the immune system time to kill and remove the bacteria.[85]

Pharmacokinetics

editThe substance is almost completely absorbed from the upper part of the small intestine. It reaches highest concentrations in the blood plasma after one to two hours and has a high plasma protein binding rate of about 80–90%. Doxycycline penetrates into almost all tissues and body fluids. Very high concentrations are found in the gallbladder, liver, kidneys, lung, breast milk, bone and genitals; low ones in saliva, aqueous humor, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and especially in inflamed meninges.[66][86][87] By comparison, the tetracycline antibiotic minocycline penetrates significantly better into the CSF and meninges.[88]

Doxycycline metabolism is negligible. It is actively excreted into the gut (in part via the gallbladder, in part directly from blood vessels), where some of it is inactivated by forming chelates. About 40% are eliminated via the kidneys, much less in people with end-stage kidney disease. The biological half-life is 18 to 22 hours (16 ± 6 hours according to another source[86]) in healthy people, slightly longer in those with end-stage kidney disease, and significantly longer in those with liver disease.[66][86][87]

Chemistry

editExpired tetracyclines or tetracyclines allowed to stand at a pH less than 2 are reported to be nephrotoxic due to the formation of a degradation product, anhydro-4-epitetracycline[89][90] causing Fanconi syndrome.[91] In the case of doxycycline, the absence of a hydroxyl group in C-6 prevents the formation of the nephrotoxic compound.[90] Nevertheless, tetracyclines and doxycycline itself have to be taken with caution in patients with kidney injury, as they can worsen azotemia due to catabolic effects.[91]

Chemical properties

editDoxycycline, doxycycline monohydrate and doxycycline hyclate are yellow, crystalline powders with a bitter taste. The latter smells faintly of ethanol, a 1% aqueous solution has a pH of 2–3, and the specific rotation is −110° cm3/dm·g in 0.01 N methanolic hydrochloric acid.[86]

| Solubility in | Doxycycline | Doxycycline monohydrate | Doxycycline hyclate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | very slightly | very slightly | freely |

| Ethanol | very slightly | very slightly | sparingly |

| Aqueous acids | freely | freely | |

| Alkali hydroxyde solutions | freely | freely | |

| Chloroform | very slightly | practically insoluble | practically insoluble |

| Diethyl ether | insoluble | practically insoluble | practically insoluble |

History

editAfter penicillin revolutionized the treatment of bacterial infections in World War II, many chemical companies moved into the field of discovering antibiotics by bioprospecting. American Cyanamid was one of these, and in the late 1940s chemists there discovered chlortetracycline, the first member of the tetracycline class of antibiotics.[4] Shortly thereafter, scientists at Pfizer discovered oxytetracycline and it was brought to market. Both compounds, like penicillin, were natural products and it was commonly believed that nature had perfected them, and further chemical changes could only degrade their effectiveness. Scientists at Pfizer led by Lloyd Conover modified these compounds, which led to the invention of tetracycline itself, the first semi-synthetic antibiotic. Charlie Stephens' group at Pfizer worked on further analogs and created one with greatly improved stability and pharmacological efficacy: doxycycline. It was clinically developed in the early 1960s and approved by the FDA in 1967.[4]

As its patent grew near to expiring in the early 1970s, the patent became the subject of lawsuit between Pfizer and International Rectifier[92] that was not resolved until 1983; at the time it was the largest litigated patent case in US history.[93] Instead of a cash payment for infringement, Pfizer took the veterinary and feed-additive businesses of International Rectifier's subsidiary, Rachelle Laboratories.[93]

In January 2013, the FDA reported shortages of some, but not all, forms of doxycycline "caused by increased demand and manufacturing issues".[94] Companies involved included an unnamed major generics manufacturer that ceased production in February 2013, Teva (which ceased production in May 2013), Mylan, Actavis, and Hikma Pharmaceuticals.[95][96] The shortage came at a particularly bad time, since there were also shortages of an alternative antibiotic, tetracycline, at the same time.[97] The market price for doxycycline dramatically increased in the United States in 2013 and early 2014 (from $20 to over $1800 for a bottle of 500 tablets),[98][99][100] before decreasing again.[101][102]

Society and culture

editDoxycycline is available worldwide under many brand names.[103] Doxycycline is available as a generic medicine.[1][10]

Research

editResearch areas on the application of doxycycline include the following medical conditions:

- macular degeneration;[104]

- rheumatoid arthritis instead of minocycline (both of which have demonstrated modest efficacy for this disease).[105]

Anti-inflammatory agent

editSome studies show doxycycline as a potential agent to possess anti-inflammatory properties acting by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) while increasing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10). Cytokines are small proteins that are secreted by immune cells and play a key role in the immune response. Some studies suggest that doxycycline can suppress the activation of the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway, which is responsible for upregulating several inflammatory mediators in various cells, including neurons; therefore, it is studied as a potential agent for treating neuroinflammation.[106][107][108]

A potential explanation of doxycycline's anti-inflammatory properties is its inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are a group of proteases known to regulate the turnover of extracellular matrix (ECM) and thus are suggested to be important in the process of several diseases associated with tissue remodeling and inflammation.[109][110][111][112] Doxycycline has been shown to inhibit MMPs,[19] including matrilysin (MMP7), by interacting with the structural zinc atom and/or calcium atoms within the structural metal center of the protein.[113][114][115]

Doxycycline also inhibits allikrein-related peptidase 5 (KLK5).[112] The inhibition of MMPs and KLK5 enzymes subsequently suppresses the expression of LL-37, a cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide that, when overexpressed, can trigger inflammatory cascades. By inhibiting LL-37 expression, doxycycline helps to mitigate these downstream inflammatory cascades, thereby reducing inflammation and the symptoms of inflammatory conditions.[112]

Doxycycline is used to treat acne vulgaris and rosacea.[116][117][15] However, there is no clear understanding of what contributes more: the bacteriostatic properties of doxycycline, which affect bacteria (such as Propionibacterium acnes[15]) on the surface of sebaceous glands even in lower doses called "submicrobial"[118][119] or "subantimicrobial",[120][121][122][15] or whether doxycycline's anti-inflammatory effects, which reduce inflammation in acne vulgaris and rosacea, including ocular rosacea,[45] contribute more to its therapeutic effectiveness against these skin conditions.[123] Subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline (SDD) can still have a bacteriostatic effect, especially when taken for extended periods, such as several months in treating acne and rosacea.[124] While the SDD is believed to have anti-inflammatory effects rather than solely antibacterial effects, SDD was proven to work by reducing inflammation associated with acne and rosacea. Still, the exact mechanisms have yet to be fully discovered.[125] One probable mechanism is doxycycline's ability to decrease the amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Inflammation in rosacea may be associated with increased production of ROS by inflammatory cells; these ROS contribute toward exacerbating symptoms. Doxycycline may reduce ROS levels and induce antioxidant activity because it directly scavenges hydroxyl radicals and singlet oxygen, helping minimize tissue damage caused by highly oxidative and inflammatory conditions.[126] Studies have shown that SDD can effectively improve acne and rosacea symptoms,[127] probably without inducing antibiotic resistance.[128] It is observed that doxycycline exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting neutrophil chemotaxis and oxidative bursts, which are common mechanisms involved in inflammation and ROS activity in rosacea and acne.[19]

Doxycycline's dual benefits as an antibacterial and anti-inflammatory make it a helpful treatment option for diseases involving inflammation not only of the skin, such as rosacea and acne, but also in conditions such as osteoarthritis or periodontitis.[129] Nevertheless, current results are inconclusive, and evidence of doxycycline's anti-inflammatory properties needs to be improved, considering conflicting reports from animal models so far.[130][131][132] Doxycycline has been studied in various immunological disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and periodontitis.[133] In these conditions, doxycycline has been researched to determine anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that could be beneficial in treating these conditions. However, a solid conclusion still needs to be provided.[134][135][136][137]

Doxycycline is also studied for its neuroprotective properties which are associated with antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. In this context, it is important to note that doxycycline is able to cross the blood–brain barrier. Several studies have shown that doxycycline inhibits dopaminergic neurodegeneration through the upregulation of axonal and synaptic proteins.[138][139] Axonal degeneration and synaptic loss are key events at the early stages of neurodegeneration and precede neuronal death in neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson's disease (PD). Therefore, the regeneration of the axonal and synaptic network might be beneficial in PD.[140] It has been demonstrated that doxycycline mimics nerve growth factor (NGF) signaling in PC12 cells. However, the involvement of this mechanism in the neuroprotective effect of doxycycline is unknown. Doxycycline is also studied in reverting inflammatory changes related to depression.[121] While there is some research on the use of doxycycline for treating major depressive disorder, the results are mixed.[121][141][142]

After a large-scale trial showed no benefit of using doxycycline in treating COVID‑19, the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) updated its guidance to not recommend the medication for the treatment of COVID‑19.[143][144] Doxycycline was expected to possess anti-inflammatory properties that could lessen the cytokine storm associated with a SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the trials did not demonstrate the expected benefit.[145] Researchers also believed that doxycycline possesses anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that could reduce the production of cytokines in COVID-19, but these supposed effects failed to improve the outcome of COVID-19 treatment.[146][147]

Wound healing

editResearch on novel drug formulations for the delivery of doxycycline in wound treatment is expanding, focusing on overcoming stability limitations for long-term storage and developing consumer-friendly, parenteral antibiotic delivery systems. The most common and practical form of doxycycline delivery is through wound dressings, which have evolved from mono- to three-layered systems to maximize healing effectiveness.[148]

Research directions on the use of doxycycline in wound healing include the continuous stabilization of doxycycline, scaling up technology and industrial production, and exploring non-contact wound treatment methods like sprays and aerosols for use in emergencies and when medical care is not readily accessible.[148]

Research reagent

editDoxycycline and other members of the tetracycline class of antibiotics are often used as research reagents in in vitro and in vivo biomedical research experiments involving bacteria as well in experiments in eukaryotic cells and organisms with inducible protein expression systems using tetracycline-controlled transcriptional activation. The mechanism of action for the antibacterial effect of tetracyclines relies on disrupting protein translation in bacteria, thereby damaging the ability of microbes to grow and repair; however protein translation is also disrupted in eukaryotic mitochondria impairing metabolism and leading to effects that can confound experimental results.[149][150] Doxycycline is also used in "tet-on" (gene expression activated by doxycycline) and "tet-off" (gene expression inactivated by doxycycline) tetracycline-controlled transcriptional activation to regulate transgene expression in organisms and cell cultures.[151] Doxycycline is more stable than tetracycline for this purpose.[151] At subantimicrobial doses, doxycycline is an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases, and has been used in various experimental systems for this purpose, such as for recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions.[152]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Doxycycline calcium". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ "Malaria". Fit for Travel. Public Health Scotland. Chemoprophylaxis. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Choosing a Drug to Prevent Malaria". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. February 2023. Doxycycline. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Nelson ML, Levy SB (December 2011). "The history of the tetracyclines". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1241 (1): 17–32. Bibcode:2011NYASA1241...17N. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06354.x. PMID 22191524. S2CID 34647314.

- ^ McFadden GI (March 2014). "Apicoplast". Current Biology. 24 (7): R262-3. Bibcode:2014CBio...24.R262M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.024. PMID 24698369.

- ^ Schlagenhauf-Lawlor P (2008). Travelers' Malaria. PMPH-USA. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-55009-336-0.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 489. ISBN 978-3-527-60749-5.

- ^ Corey EJ (2013). Drug discovery practices, processes, and perspectives. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-118-35446-9. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b Hamilton RJ (2011). Tarascon pharmacopoeia (12th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-4496-0067-9.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Doxycycline Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Sweet RL, Schachter J, Landers DV, Ohm-Smith M, Robbie MO (March 1988). "Treatment of hospitalized patients with acute pelvic inflammatory disease: comparison of cefotetan plus doxycycline and cefoxitin plus doxycycline". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 158 (3 Pt 2): 736–41. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)44537-0. PMID 3162653.

- ^ Gjønnaess H, Holten E (1978). "Doxycycline (Vibramycin) in pelvic inflammatory disease". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 57 (2): 137–9. doi:10.3109/00016347809155893. PMID 345730. S2CID 28328073.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Holmes NE, Charles PG (5 January 2009). "Safety and Efficacy Review of Doxycycline". Clinical Medicine. Therapeutics. 1: CMT.S2035. doi:10.4137/CMT.S2035. S2CID 58790579.

- ^ Määttä M, Kari O, Tervahartiala T, Peltonen S, Kari M, Saari M, et al. (August 2006). "Tear fluid levels of MMP-8 are elevated in ocular rosacea--treatment effect of oral doxycycline". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv für Klinische und Experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 244 (8): 957–62. doi:10.1007/s00417-005-0212-3. PMID 16411105. S2CID 20540747.

- ^ Quarterman MJ, Johnson DW, Abele DC, Lesher JL, Hull DS, Davis LS (January 1997). "Ocular rosacea. Signs, symptoms, and tear studies before and after treatment with doxycycline". Archives of Dermatology. 133 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1001/archderm.133.1.49 (inactive 11 November 2024). PMID 9006372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Walker DH, Paddock CD, Dumler JS (November 2008). "Emerging and re-emerging tick-transmitted rickettsial and ehrlichial infections". The Medical Clinics of North America. 92 (6): 1345–61, x. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2008.06.002. PMID 19061755.

- ^ a b c Lee JJ, Chien AL (April 2024). "Rosacea in Older Adults and Pharmacologic Treatments". Drugs Aging. 41 (5): 407–421. doi:10.1007/s40266-024-01115-y. PMID 38649625.

- ^ Rekart ML (December 2004). "Doxycycline:" New" treatment of choice for genital chlamydia infections". British Columbia Medical Journal. 46 (10): 503. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ^ "Doxycycline spectrum of bacterial susceptibility and Resistance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Stoddard RA, Galloway RL, Guerra MA (10 July 2015). "Leptospirosis". Yellow Book. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Nadelman RB, Luger SW, Frank E, Wisniewski M, Collins JJ, Wormser GP (August 1992). "Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in the treatment of early Lyme disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 117 (4): 273–80. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-117-4-273. PMID 1637021. S2CID 23358315.

- ^ Luger SW, Paparone P, Wormser GP, Nadelman RB, Grunwaldt E, Gomez G, et al. (March 1995). "Comparison of cefuroxime axetil and doxycycline in treatment of patients with early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 39 (3): 661–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.39.3.661. PMC 162601. PMID 7793869.

- ^ Nadelman RB, Nowakowski J, Fish D, Falco RC, Freeman K, McKenna D, et al. (July 2001). "Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite". The New England Journal of Medicine. 345 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450201. PMID 11450675.

- ^ Karlsson M, Hammers-Berggren S, Lindquist L, Stiernstedt G, Svenungsson B (July 1994). "Comparison of intravenous penicillin G and oral doxycycline for treatment of Lyme neuroborreliosis". Neurology. 44 (7): 1203–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.44.7.1203. PMID 8035916. S2CID 38661885.

- ^ Weinstein RS (November 1996). "Human ehrlichiosis". American Family Physician. 54 (6): 1971–6. PMID 8900357.

- ^ Karlsson U, Bjöersdorff A, Massung RF, Christensson B (2001). "Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis--a clinical case in Scandinavia". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 33 (1): 73–4. doi:10.1080/003655401750064130. PMID 11234985. S2CID 218880245.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "Doxycycline, ANDA no. 065055 Label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af "Doxycycline, ANDA no. 065454 Label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 16 July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2013.

- ^ Gupta N, Boodman C, Jouego CG, Van Den Broucke S (December 2023). "Doxycycline vs azithromycin in patients with scrub typhus: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis". BMC Infect Dis. 23 (1): 884. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08893-7. PMC 10726538. PMID 38110855.

- ^ Anderson A, Bijlmer H, Fournier PE, Graves S, Hartzell J, Kersh GJ, et al. (March 2013). "Diagnosis and management of Q fever--United States, 2013: recommendations from CDC and the Q Fever Working Group". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 62 (RR-03): 1–30. PMID 23535757. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014.

- ^ Biggs HM, Behravesh CB, Bradley KK, Dahlgren FS, Drexler NA, Dumler JS, et al. (2016). "Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Other Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis — United States". MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 65 (2): 1–44. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6502a1. PMID 27172113. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Schutze GE, Regan J, Bradley J (1 July 2010). "Use doxycycline as first-line treatment for rickettsial diseases". AAP News. American Academy of Pediatrics. ISSN 1556-3332. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Spotted fever group rickettsial disease | DermNet". 26 October 2023. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Okada T, Morozumi M, Tajima T, Hasegawa M, Sakata H, Ohnari S, et al. (December 2012). "Rapid effectiveness of minocycline or doxycycline against macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in a 2011 outbreak among Japanese children". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 55 (12): 1642–9. doi:10.1093/cid/cis784. PMID 22972867.

- ^ "Lyme disease. Treatment". 21 December 2018. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016.

- ^ Taylor-Salmon E, Shapiro ED (April 2024). "Tick-borne infections in children in North America". Curr Opin Pediatr. 36 (2): 156–163. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000001326. PMC 10932821. PMID 38167816.

- ^ Roca Mora MM, Cunha LM, Godoi A, Donadon I, Clemente M, Marcolin P, et al. (June 2024). "Shorter versus longer duration of antimicrobial therapy for early Lyme disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 109 (2): 116215. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2024.116215. PMID 38493509.

- ^ Dreno B, Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, Kang S, Leyden JJ, et al. (2014). "Antibiotic stewardship in dermatology: limiting antibiotic use in acne". European Journal of Dermatology. 24 (3): 330–4. doi:10.1684/ejd.2014.2309. PMID 24721547. S2CID 28700961.

- ^ Garner SE, Eady A, Bennett C, Newton JN, Thomas K, Popescu CM, et al. (Cochrane Skin Group) (August 2012). "Minocycline for acne vulgaris: efficacy and safety". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (8): CD002086. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002086.pub2. PMC 7017847. PMID 22895927.

- ^ Sgolastra F, Petrucci A, Gatto R, Giannoni M, Monaco A (November 2011). "Long-term efficacy of subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline as an adjunctive treatment to scaling and root planing: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Periodontology. 82 (11): 1570–1581. doi:10.1902/jop.2011.110026. PMID 21417590.

- ^ van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, van der Linden MM, Charland L, et al. (Cochrane Skin Group) (April 2015). "Interventions for rosacea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD003262. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003262.pub5. PMC 6481562. PMID 25919144.

- ^ Cao H, Yang G, Wang Y, Liu JP, Smith CA, Luo H, et al. (Cochrane Skin Group) (January 2015). "Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD009436. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009436.pub2. PMC 4486007. PMID 25597924.

- ^ a b c Avraham S, Khaslavsky S, Kashetsky N, Starkey SY, Zaslavsky K, Lam JM, et al. (February 2024). "Therapie der okulären Rosazea: Eine systematische Literatur-Übersicht: Treatment of ocular rosacea: a systematic review". J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 22 (2): 167–176. doi:10.1111/ddg.15290_g. PMID 38361192.

- ^ a b "Doxycycline Dosage Guide + Max Dose, Adjustments". Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Vanbaelen T, Manoharan-Basil SS, Kenyon C (April 2024). "45 years of tetracycline post exposure prophylaxis for STIs and the risk of tetracycline resistance: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Infect Dis. 24 (1): 376. doi:10.1186/s12879-024-09275-3. PMC 10996150. PMID 38575877.

- ^ Samuel K (26 May 2023). "Using antibiotics to prevent STIs". Aidsmap. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Stewart J (21 December 2023). "Doxycycline Prophylaxis to Prevent Sexually Transmitted Infections in Women". New England Journal of Medicine. 389 (25): 2331–2340. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2304007. PMC 10805625. PMID 38118022.

- ^ Cornelisse VJ, Riley B, Medland NA (April 2024). "Australian consensus statement on doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) for the prevention of syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men". Med J Aust. 220 (7): 381–386. doi:10.5694/mja2.52258. PMID 38479437.

- ^ "Guidelines for the Use of Doxycycline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis for Bacterial STI Prevention". CDC. 29 September 2023. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "2023 Consensus Statement on doxycycline prophylaxis (Doxy-PEP) for the prevention of syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Australia". Australasian Society for HIV Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Highleyman L (5 March 2024). "Sexually transmitted infections in San Francisco have fallen since doxyPEP roll-out". Aidsmap. Archived from the original on 10 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Hashemi SH, Gachkar L, Keramat F, Mamani M, Hajilooi M, Janbakhsh A, et al. (April 2012). "Comparison of doxycycline-streptomycin, doxycycline-rifampin, and ofloxacin-rifampin in the treatment of brucellosis: a randomized clinical trial". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 16 (4): e247–e251. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2011.12.003. PMID 22296864. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Doryx- doxycycline hyclate tablet, delayed release". DailyMed. 23 October 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Malaria - Chapter 3 - 2018 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". CDC. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Dahl EL, Shock JL, Shenai BR, Gut J, DeRisi JL, Rosenthal PJ (September 2006). "Tetracyclines specifically target the apicoplast of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 50 (9): 3124–31. doi:10.1128/AAC.00394-06. PMC 1563505. PMID 16940111.

- ^ Holmes NE, Charles PG (2009). "Safety and Efficacy Review of Doxycycline". Clinical Medicine. Therapeutics. 1: CMT.S2035. doi:10.4137/CMT.S2035.

- ^ Gaillard T, Madamet M, Pradines B (November 2015). "Tetracyclines in malaria". Malar J. 14: 445. doi:10.1186/s12936-015-0980-0. PMC 4641395. PMID 26555664.

- ^ Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2015. p. 246. ISBN 978-92-4-154912-7.

- ^ Hoerauf A, Mand S, Fischer K, Kruppa T, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Debrah AY, et al. (November 2003). "Doxycycline as a novel strategy against bancroftian filariasis-depletion of Wolbachia endosymbionts from Wuchereria bancrofti and stop of microfilaria production". Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 192 (4): 211–6. doi:10.1007/s00430-002-0174-6. PMID 12684759. S2CID 23349595.

- ^ Taylor MJ, Makunde WH, McGarry HF, Turner JD, Mand S, Hoerauf A (2005). "Macrofilaricidal activity after doxycycline treatment of Wuchereria bancrofti: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet. 365 (9477): 2116–21. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66591-9. PMID 15964448. S2CID 21382828.

- ^ a b c d "Doxycycline hyclate Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data" (PDF). toku-e.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ Kaufman JA, Lee MJ (22 June 2013). Vascular and interventional radiology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. ISBN 978-0-323-07672-2. OCLC 853455295.

- ^ Müller M, Butler J, Heidecker B (7 January 2020). "Emerging therapies in transthyretin amyloidosis – a new wave of hope after years of stagnancy?". European Journal of Heart Failure. 22 (1). Wiley: 39–53. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1695. PMID 31912620.

- ^ a b c d Haberfeld H, ed. (2020). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Doxycyclin Genericon 200 mg lösliche Tabletten.

- ^ PubMed Health (1 July 2016). "Doxycycline (By mouth)". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Chung AM, Reed MD, Blumer JL (2002). "Antibiotics and breast-feeding: a critical review of the literature". Paediatric Drugs. 4 (12): 817–37. doi:10.2165/00128072-200204120-00006. PMID 12431134. S2CID 8595370.

- ^ Mylonas I (January 2011). "Antibiotic chemotherapy during pregnancy and lactation period: aspects for consideration". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 283 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1007/s00404-010-1646-3. PMID 20814687. S2CID 25492353.

- ^ "Bioterrorism and Drug Preparedness - Doxycycline Use by Pregnant and Lactating Women". FDA. 3 November 2018. Archived from the original on 8 February 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Gaillard T, Briolant S, Madamet M, Pradines B (April 2017). "The end of a dogma: the safety of doxycycline use in young children for malaria treatment". Malaria Journal. 16 (1): 148. doi:10.1186/s12936-017-1797-9. PMC 5390373. PMID 28407772.

- ^ a b Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E (2015). Top 100 drugs: clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. Churchill Livingstone. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- ^ a b Riond JL, Riviere JE (October 1988). "Pharmacology and toxicology of doxycycline". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 30 (5): 431–43. PMID 3055652.

- ^ Affolter K, Samowitz W, Boynton K, Kelly ED (August 2017). "Doxycycline-induced gastrointestinal injury". Human Pathology. 66: 212–215. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2017.02.011. PMID 28286288.

- ^ Hung YP, Lee JC, Lin HJ, Liu HC, Wu YH, Tsai PJ, et al. (June 2015). "Doxycycline and Tigecycline: Two Friendly Drugs with a Low Association with Clostridium Difficile Infection". Antibiotics. 4 (2): 216–29. doi:10.3390/antibiotics4020216. PMC 4790331. PMID 27025622.

- ^ Tan KR, Magill AJ, Parise ME, Arguin PM (April 2011). "Doxycycline for malaria chemoprophylaxis and treatment: report from the CDC expert meeting on malaria chemoprophylaxis". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 84 (4): 517–31. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0285. PMC 3062442. PMID 21460003.

- ^ a b Dréno B, Bettoli V, Ochsendorf F, Layton A, Mobacken H, Degreef H (November–December 2004). "European recommendations on the use of oral antibiotics for acne" (PDF). European Journal of Dermatology. 14 (6): 391–9. PMID 15564203.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Lee TW, Russell L, Deng M, Gibson PR (August 2013). "Association of doxycycline use with the development of gastroenteritis, irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease in Australians deployed abroad". Internal Medicine Journal. 43 (8): 919–26. doi:10.1111/imj.12179. PMID 23656210. S2CID 9418654.

- ^ Margolis DJ, Fanelli M, Hoffstad O, Lewis JD (December 2010). "Potential association between the oral tetracycline class of antimicrobials used to treat acne and inflammatory bowel disease". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 105 (12): 2610–6. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.303. PMID 20700115. S2CID 20085592.

- ^ Archer JS, Archer DF (June 2002). "Oral contraceptive efficacy and antibiotic interaction: a myth debunked". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 46 (6): 917–23. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120448. PMID 12063491.

- ^ DeRossi SS, Hersh EV (October 2002). "Antibiotics and oral contraceptives". Dental Clinics of North America. 46 (4): 653–64. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.620.9933. doi:10.1016/S0011-8532(02)00017-4. PMID 12436822.

- ^ Flower R, Rang HP, Dale MM, Ritter JM, Henderson G (2012). Rang & Dale's Pharmacology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-7020-3471-8.

- ^ a b Maaland MG, Papich MG, Turnidge J, Guardabassi L (November 2013). "Pharmacodynamics of doxycycline and tetracycline against Staphylococcus pseudintermedius: proposal of canine-specific breakpoints for doxycycline". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 51 (11): 3547–54. doi:10.1128/JCM.01498-13. PMC 3889732. PMID 23966509.

- ^ Agwuh KN, MacGowan A (August 2006). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the tetracyclines including glycylcyclines". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 58 (2): 256–65. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl224. PMID 16816396.

- ^ "Doxycycline". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 10 November 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Dinnendahl, V, Fricke, U, eds. (2010). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 4 (24 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. Doxycyclin. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ a b Doxycycline Professional Drug Facts. Accessed 5 August 2020.

- ^ Haberfeld H, ed. (2020). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Minostad 50 mg-Kapseln.

- ^ "Principles and methods for the assessment of nephrotoxicity associated with exposure to chemicals". Environmental health criteria. Vol. 119. World Health Organization (WHO). 1991. ISBN 92-4-157119-5. ISSN 0250-863X. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ^ a b Williams DA, Foye WO, Lemke TL (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry (6th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- ^ a b Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.).

- ^ "Pfizer, Inc. v. International Rectifier Corp., 545 F. Supp. 486 (C.D. Cal. 1980)". Justia Law. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Pfizer to Get Rachelle Units". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 6 July 1983. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Nationwide Shortage of Doxycycline: Resources for Providers and Recommendations for Patient Care". CDC Health Alert Network. 12 June 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Doxycycline Capsules and Tablets". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 12 December 2014. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Doxycycline Hyclate Injection". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ "FDA reports shortage of doxycycline antibiotic. What are your options?". Consumer Reports News. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Sudden increase in cost of common drug concerns many". WSMV-TV. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2014.

- ^ Rosenthal E (7 October 2014). "Officials Question the Rising Costs of Generic Drugs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017.

- ^ Palmer E (13 March 2014). "Hikma hits the jackpot with doxycycline shortage". FiercePharmaManufacturing. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ "Costco Drug Information". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Doxycycline Hyclate Prices and Doxycycline Hyclate Coupons". GoodRx. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "International availability for doxycycline". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ Leung E, Landa G (September 2013). "Update on current and future novel therapies for dry age-related macular degeneration". Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 6 (5): 565–79. doi:10.1586/17512433.2013.829645. PMID 23971874. S2CID 26680094.

- ^ Greenwald RA (December 2011). "The road forward: the scientific basis for tetracycline treatment of arthritic disorders". Pharmacological Research. 64 (6): 610–3. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2011.06.010. PMID 21723947.

- ^ Singh S, Khanna D, Kalra S (2021). "Minocycline and Doxycycline: More Than Antibiotics". Curr Mol Pharmacol. 14 (6): 1046–1065. doi:10.2174/1874467214666210210122628. PMID 33568043. S2CID 231881758. Archived from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Henehan M, Montuno M, De Benedetto A (November 2017). "Doxycycline as an anti-inflammatory agent: updates in dermatology". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 31 (11): 1800–1808. doi:10.1111/jdv.14345. PMID 28516469. S2CID 37723341.

- ^ Berman B, Perez OA, Zell D (January 2007). "Update on rosacea and anti-inflammatory-dose doxycycline". Drugs of Today. 43 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1358/dot.2007.43.1.1025697. PMID 17315050.

- ^ Lagente V, Victoni T, Boichot E (2011). "Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors as New Anti-inflammatory Drugs". Proteases and Their Receptors in Inflammation. Progress in Inflammation Research. Springer. pp. 101–122. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-0157-7_5. ISBN 978-3-0348-0156-0.

- ^ Wang S, Liu C, Liu X, He Y, Shen D, Luo Q, et al. (October 2017). "Effects of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor doxycycline and CD147 antagonist peptide-9 on gallbladder carcinoma cell lines". Tumour Biol. 39 (10): 1010428317718192. doi:10.1177/1010428317718192. PMID 29034777. S2CID 206614670.

- ^ Jung JJ, Razavian M, Kim HY, Ye Y, Golestani R, Toczek J, et al. (September 2016). "Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, doxycycline and progression of calcific aortic valve disease in hyperlipidemic mice". Sci Rep. 6: 32659. Bibcode:2016NatSR...632659J. doi:10.1038/srep32659. PMC 5020643. PMID 27619752.

- ^ a b c Wehrli JM, Xia Y, Offenhammer B, Kleim B, Müller D, Bach DR (February 2023). "Effect of the Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitor Doxycycline on Human Trace Fear Memory". eNeuro. 10 (2). doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0243-22.2023. PMC 9961363. PMID 36759188.

- ^ Liu J, Xiong W, Baca-Regen L, Nagase H, Baxter BT (December 2003). "Mechanism of inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression by doxycycline in human aortic smooth muscle cells". J Vasc Surg. 38 (6): 1376–83. doi:10.1016/s0741-5214(03)01022-x. PMID 14681644.

- ^ García RA, Pantazatos DP, Gessner CR, Go KV, Woods VL, Villarreal FJ (April 2005). "Molecular interactions between matrilysin and the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor doxycycline investigated by deuterium exchange mass spectrometry". Mol Pharmacol. 67 (4): 1128–36. doi:10.1124/mol.104.006346. PMID 15665254. S2CID 23253029.

- ^ Liu J, Khalil RA (2017). "Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors as Investigational and Therapeutic Tools in Unrestrained Tissue Remodeling and Pathological Disorders". Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 148: 355–420. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.04.003. ISBN 978-0-12-812776-6. PMC 5548434. PMID 28662828.

- ^ Eichenfield DZ, Sprague J, Eichenfield LF (November 2021). "Management of Acne Vulgaris: A Review". JAMA. 326 (20): 2055–2067. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.17633. PMID 34812859. S2CID 244490539.

- ^ Baldwin H (September 2020). "Oral Antibiotic Treatment Options for Acne Vulgaris". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 13 (9): 26–32. PMC 7577330. PMID 33133338.

- ^ Parish LC, Parish JL, Routh HB, Witkowski JA (2005). "The treatment of acne vulgaris with low dosage doxycycline". Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 13 (3): 156–9. PMID 16146617.

- ^ Stein Gold LF (June 2016). "Acne: What's New". Semin Cutan Med Surg. 35 (6 Suppl): S114–6. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2016.036. PMID 27538054.

- ^ Kontochristopoulos G, Tsiogka A, Agiasofitou E, Kapsiocha A, Soulaidopoulos S, Liakou AI, et al. (November 2022). "Efficacy of Subantimicrobial, Modified-Release Doxycycline Compared to Regular-Release Doxycycline for the Treatment of Hidradenitis Suppurativa". Skin Appendage Disord. 8 (6): 476–481. doi:10.1159/000524762. PMC 9672876. PMID 36407641.

- ^ a b c Mello BSF, Chaves Filho AJM, Custódio CS, Rodrigues PA, Carletti JV, Vasconcelos SMM, et al. (September 2021). "Doxycycline at subantimicrobial dose combined with escitalopram reverses depressive-like behavior and neuroinflammatory hippocampal alterations in the lipopolysaccharide model of depression". J Affect Disord. 292: 733–745. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.083. PMID 34161892.

- ^ Bikowski JB (2003). "Subantimicrobial dose doxycycline for acne and rosacea". Skinmed. 2 (4): 234–45. doi:10.1111/j.1540-9740.2003.03014.x. PMID 14673277.

- ^ Navarro-Triviño FJ, Pérez-López I, Ruiz-Villaverde R (September 2020). "Doxycycline, an Antibiotic or an Anti-Inflammatory Agent? The Most Common Uses in Dermatology". Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 111 (7): 561–566. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2019.12.006. PMID 32401726. S2CID 218635190.

- ^ Zolotarev O, Khakimova A, Rahim F, Senel E, Zatsman I, Gu D (October 2023). "Scientometric analysis of trends in global research on acne treatment". Int J Womens Dermatol. 9 (3): e082. doi:10.1097/JW9.0000000000000082. PMC 10378739. PMID 37521754.

- ^ Shields A, Barbieri JS (August 2023). "From Breakouts to Bargains: Strategies for Patient-Centered, Cost-effective Acne Care". Cutis. 112 (2): E24–E29. doi:10.12788/cutis.0844. PMC 10951614. PMID 37820334. S2CID 261786019.

- ^ Akamatsu H, Asada M, Komura J, Asada Y, Niwa Y (1992). "Effect of doxycycline on the generation of reactive oxygen species: a possible mechanism of action of acne therapy with doxycycline". Acta Derm Venereol. 72 (3): 178–9. doi:10.2340/0001555572178179. PMID 1357852. S2CID 45726787.

- ^ Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, Alikhan A, Baldwin HE, Berson DS, et al. (May 2016). "Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris". J Am Acad Dermatol. 74 (5): 945–73.e33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. PMID 26897386.

- ^ Wise RD (2007). "Submicrobial doxycycline and rosacea". Compr Ther. 33 (2): 78–81. doi:10.1007/s12019-007-8003-x. PMID 18004018. S2CID 28262106.

- ^ Ahuja TS (August 2003). "Doxycycline decreases proteinuria in glomerulonephritis". Am J Kidney Dis. 42 (2): 376–80. doi:10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00662-0. PMID 12900822.

- ^ Patel A, Khande H, Periasamy H, Mokale S (June 2020). "Immunomodulatory Effect of Doxycycline Ameliorates Systemic and Pulmonary Inflammation in a Murine Polymicrobial Sepsis Model". Inflammation. 43 (3): 1035–1043. doi:10.1007/s10753-020-01188-y. PMC 7224120. PMID 31955291.

- ^ Martin V, Bettencourt AF, Santos C, Fernandes MH, Gomes PS (September 2023). "Unveiling the Osteogenic Potential of Tetracyclines: A Comparative Study in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells". Cells. 12 (18): 2244. doi:10.3390/cells12182244. PMC 10526833. PMID 37759467.

- ^ Waitayangkoon P, Moon SJ, Tirupur Ponnusamy JJ, Zeng L, Driban J, McAlindon T (September 2023). "Long-Term Safety Profiles Macrolides and Tetracyclines: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". J Clin Pharmacol. 64 (2): 164–177. doi:10.1002/jcph.2358. PMID 37751595. S2CID 263151406.

- ^ Orylska-Ratynska M, Placek W, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A (June 2022). "Tetracyclines-An Important Therapeutic Tool for Dermatologists". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19 (12): 7246. doi:10.3390/ijerph19127246. PMC 9224192. PMID 35742496.

- ^ Santos M, Gonçalves-Santos E, Gonçalves R, Santos E, Campos C, Bastos D, et al. (May 2021). "Doxycycline aggravates granulomatous inflammation and lung microstructural remodeling induced by Schistosoma mansoni infection". Int Immunopharmacol. 94: 107462. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107462. PMID 33611055. S2CID 231988574.

- ^ Florou DT, Mavropoulos A, Dardiotis E, Tsimourtou V, Siokas V, Aloizou AM, et al. (2021). "Tetracyclines Diminish In Vitro IFN-γ and IL-17-Producing Adaptive and Innate Immune Cells in Multiple Sclerosis". Front Immunol. 12: 739186. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.739186. PMC 8662812. PMID 34899697.

- ^ Garrido-Mesa J, Adams K, Galvez J, Garrido-Mesa N (May 2022). "Repurposing tetracyclines for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and severe COVID-19: a critical discussion of recent publications". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 31 (5): 475–482. doi:10.1080/13543784.2022.2054325. PMC 9115781. PMID 35294307.

- ^ de Witte LD, Munk Laursen T, Corcoran CM, Kahn RS, Birnbaum R, Munk-Olsen T, et al. (July 2023). "A Sex-Dependent Association Between Doxycycline Use and Development of Schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull. 49 (4): 953–961. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbad008. PMC 10318877. PMID 36869773.

- ^ Santa-Cecília FV, Leite CA, Del-Bel E, Raisman-Vozari R (May 2019). "The Neuroprotective Effect of Doxycycline on Neurodegenerative Diseases". Neurotox Res. 35 (4): 981–986. doi:10.1007/s12640-019-00015-z. PMID 30798507. S2CID 71147889.

- ^ Paldino E, Balducci C, La Vitola P, Artioli L, D'Angelo V, Giampà C, et al. (April 2020). "Neuroprotective Effects of Doxycycline in the R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington's Disease". Mol Neurobiol. 57 (4): 1889–1903. doi:10.1007/s12035-019-01847-8. PMC 7118056. PMID 31879858.

- ^ do Amaral L, Dos Santos NAG, Sisti FM, Del Bel E, Dos Santos AC (August 2023). "Doxycycline inhibits dopaminergic neurodegeneration through upregulation of axonal and synaptic proteins". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 396 (8): 1787–1796. doi:10.1007/s00210-023-02435-3. PMID 36843128. S2CID 257218181.

- ^ Lee JW, Lee H, Kang HY (October 2021). "Association between depression and antibiotic use: analysis of population-based National Health Insurance claims data". BMC Psychiatry. 21 (1): 536. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03550-2. PMC 8554858. PMID 34711196.

- ^ Leyder E, Suresh P, Jun R, Overbey K, Banerjee T, Melnikova T, et al. (February 2023). "Depression-related phenotypes at early stages of Aβ and tau accumulation in inducible Alzheimer's disease mouse model: Task-oriented and concept-driven interpretations". Behav Brain Res. 438: 114187. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114187. PMID 36343696. S2CID 253300844.

- ^ "Platform trial rules out treatments for COVID-19". NIHR Evidence. 31 May 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_50873. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Butler CC, Yu LM, Dorward J, Gbinigie O, Hayward G, Saville BR, et al. (September 2021). "Doxycycline for community treatment of suspected COVID-19 in people at high risk of adverse outcomes in the UK (PRINCIPLE): a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 9 (9): 1010–1020. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00310-6. PMC 8315758. PMID 34329624.

- ^ Sharma S, Bhatt P, Asdaq S, Alshammari M, Alanazi A, Alrasheedi N, et al. (May 2022). "Combined therapy with ivermectin and doxycycline can effectively alleviate the cytokine storm of COVID-19 infection amid vaccination drive: A narrative review". J Infect Public Health. 15 (5): 566–572. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2022.03.014. PMC 8964533. PMID 35462191.

- ^ Ohe M (February 2022). "Multi-drug Treatment for COVID-19-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome". Turk J Pharm Sci. 19 (1): 101–103. doi:10.4274/tjps.galenos.2021.63060. PMC 8892560. PMID 35227056.

- ^ Dorobisz K, Dorobisz T, Janczak D, Zatoński T (2021). "Doxycycline in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Therapy". Ther Clin Risk Manag. 17: 1023–1026. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S314923. PMC 8464303. PMID 34584416.

- ^ a b Saliy O, Popova M, Tarasenko H, Getalo O (April 2024). "Development strategy of novel drug formulations for the delivery of doxycycline in the treatment of wounds of various etiologies". Eur J Pharm Sci. 195: 106636. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106636. PMID 38185273.

- ^ Moullan N, Mouchiroud L, Wang X, Ryu D, Williams EG, Mottis A, et al. (March 2015). "Tetracyclines Disturb Mitochondrial Function across Eukaryotic Models: A Call for Caution in Biomedical Research". Cell Reports. 10 (10): 1681–1691. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.034. PMC 4565776. PMID 25772356.

- ^ Chatzispyrou IA, Held NM, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J, Houtkooper RH (November 2015). "Tetracycline antibiotics impair mitochondrial function and its experimental use confounds research". Cancer Research. 75 (21): 4446–9. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1626. PMC 4631686. PMID 26475870.

- ^ a b Gossen M, Freundlieb S, Bender G, Müller G, Hillen W, Bujard H (June 1995). "Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells". Science. 268 (5218): 1766–9. Bibcode:1995Sci...268.1766G. doi:10.1126/science.7792603. PMID 7792603.

- ^ Dursun D, Kim MC, Solomon A, Pflugfelder SC (July 2001). "Treatment of recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions with inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-9, doxycycline and corticosteroids". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 132 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(01)00913-8. PMID 11438047.