| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Coreg |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697042 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 25–35% |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6, CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 7–10 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (16%), Feces (60%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

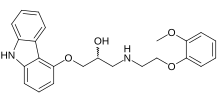

| Formula | C24H26N2O4 |

| Molar mass | 406.474 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Carvedilol is a nonselective beta blocker/alpha-1 blocker used in the treatment of mild to severe congestive heart failure (CHF) and high blood pressure. It is marketed under various trade names including Carvil (Zydus Cadila), Coreg (GSK), Dilatrend , Kredex (Roche), Eucardic (Roche), and Carloc (Cipla) as a generic drug (as of September 5, 2007 in the U.S.),[1] and as a controlled-release formulation, marketed in the US as Coreg CR (GSK). Carvedilol was discovered by Fritz Wiedemann at Boehringer Mannheim.[2] It has had a significant role in the treatment of congestive heart failure.

Medical use edit

Carvedilol is indicated in the management of congestive heart failure (CHF), as an adjunct to conventional treatments (ACE inhibitors and diuretics). The use of carvedilol has been shown to provide additional morbidity and mortality benefits in severe CHF.[3]

Side effects edit

The most common side effects include dizziness, fatigue, low blood pressure, diarrhea, weakness, slowed heart rate, and weight gain.[4]

Pharmacology edit

Carvedilol is both a beta blocker (β1, β2) and alpha blocker (α1):

- Norepinephrine stimulates the nerves that control the muscles of the heart by binding to the β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. Carvedilol blocks the binding to those receptors,[5] which slows the heart rhythm and reduces the force of the heart's pumping. This lowers blood pressure thus reducing the workload of the heart, which is particularly beneficial in heart failure patients.

- Norepinephrine also binds to the α1-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels, causing them to constrict and raise blood pressure. Carvedilol blocks this binding to the α1-adrenergic receptors too,[6] which also lowers blood pressure.

Relative to other beta blockers, carvedilol has minimal inverse agonist activity.[7] This suggests that carvedilol has a reduced negative chronotropic and inotropic effect compared to other beta blockers, which may decrease its potential to worsen symptoms of heart failure. However, to date this theoretical benefit has not been established in clinical trials, and the current version of the ACC/AHA guidelines on congestive heart failure management does not give preference to carvedilol over other beta-blockers.[citation needed]

Carvedilol also acts as a functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase.[8]

Carvedilol is known to act as a calcium channel blocker at high doses.[9]

Carvedilol is lipid-soluble and is able to cross the blood-brain-barrier.[10][11][12]

Enantiomers edit

Carvedilol has enantiomers with distinct pharmacodynamics.[13]

The term "racemic carvedilol" is sometimes used to explicitly denote that both enantiomers are applied.[14]

Society and culture edit

U.S. supply issues edit

On January 10, 2006 carvedilol supply became limited in the United States, due to changes in documentation procedures at a plant. This was lifted on April 27, 2006 in a Dear Pharmacist letter.[15]

Approval of controlled-release formulation edit

On October 20, 2006, the FDA approved a controlled release formulation of carvedilol; it is marketed as Coreg CR.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Press Release, FDA Approves First Generic Versions of Coreg, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Sep. 5, 2007

- ^ U.S. Patent 4503067

- ^ Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB; et al. (October 2002). "Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study". Circulation. 106 (17): 2194–9. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000035653.72855.BF. PMID 12390947. S2CID 13377929.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carvedilol Official FDA information, side effects and uses. Drugs.com, October 11, 2009.

- ^ Stafylas PC, Sarafidis PA (2008). "Carvedilol in hypertension treatment". Vasc Health Risk Manag. 4 (1): 23–30. doi:10.2147/vhrm.2008.04.01.23. PMC 2464772. PMID 18629377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Othman AA, Tenero DM, Boyle DA, Eddington ND, Fossler MJ (2007). "Population pharmacokinetics of S(−)-carvedilol in healthy volunteers after administration of the immediate-release (IR) and the new controlled-release (CR) dosage forms of the racemate". AAPS J. 9 (2): E208–18. doi:10.1208/aapsj0902023. PMC 2751410. PMID 17614362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vanderhoff BT, Ruppel HM, Amsterdam PB (November 1998). "Carvedilol: the new role of beta blockers in congestive heart failure". Am Fam Physician. 58 (7): 1627–34, 1641–2. PMID 9824960.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, Mühle C, Terfloth L, Groemer T, Spitzer G, Liedl K, Gulbins E, Tripal P (2011). "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. PMC 3166082. PMID 21909365.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Stephen Brennan (2009). MRCP Cardiology MCQs. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-84619-358-3.

- ^ Manuchair Ebadi (29 December 1997). CRC Desk Reference of Clinical Pharmacology. CRC Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-8493-9683-0.

- ^ Stephen Jackson; Paul Jansen; Arduino Mangoni (22 April 2009). Prescribing for Elderly Patients. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-0-470-02429-4.

- ^ Joseph Colombo; Rohit Arora; Nicholas L. DePace; Charlotte Ball (22 September 2014). Clinical Autonomic Dysfunction: Measurement, Indications, Therapies, and Outcomes. Springer. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-3-319-07371-2.

- ^ Horiuchi I, Nozawa T, Fujii N; et al. (May 2008). "Pharmacokinetics of R- and S-carvedilol in routinely treated Japanese patients with heart failure". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31 (5): 976–80. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.976. PMID 18451529.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [dead link] - ^ Takekuma Y, Takenaka T, Yamazaki K, Ueno K, Sugawara M (November 2007). "Stereoselective metabolism of racemic carvedilol by UGT1A1 and UGT2B7, and effects of mutation of these enzymes on glucuronidation activity". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30 (11): 2146–53. doi:10.1248/bpb.30.2146. PMID 17978490.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [dead link] - ^ [1][dead link]

Further reading edit

- Chakraborty, Subhashis; Shukla, Dali; Mishra, Brahmeshwar; Singh, Sanjay (February 2010). "Clinical updates on carvedilol: a first choice β-blocker in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 6 (2): 237–250. doi:10.1517/17425250903540220. PMID 20073998. S2CID 25670550.

External links edit

- Coreg CR official website

- Physicians Desk Reference Info on Carvedilol

- Info on carvedilol through rxlist.com

Category:Beta blockers Category:Carbazoles Category:Phenol ethers Category:Alcohols Category:Amines