| Great Mosque of Herat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Herat, Afghanistan |

| Geographic coordinates | 34°20′35″N 62°11′45″E / 34.34306°N 62.19583°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Islamic |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 180m |

| Width | 120m |

| Minaret(s) | 12 |

| Minaret height | 12-36m |

| Materials | brick, stone, glazed ceramics |

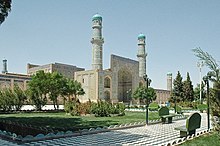

The Great Mosque of Herat (Persian: مسجد جامع هرات, Masjid-i Jāmi‘-i Herāt) or "Jami Masjid of Herat,"[1] is a mosque in the city of Herat, in the Herat Province of north-western Afghanistan. It was built by the Ghurids, under the rule of Sultan Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad Ghori, who laid its foundation in 1200 CE. Later, it was extended several times as Herat changed rulers down the centuries from the Karts, Timurids, Mughals and then the Uzbeks, all of whom supported the mosque. The fundamental structure of the mosque from the Ghurid period has been preserved, but parts have been added and modified. The Friday Mosque in Herat was given its present appearance during the 20th century.

Apart from numerous small neighborhood mosques for daily prayer, most communities in the Islamic world have a larger mosque, a congregational mosque for Friday services with a sermon. The Jama Masjid was not always the largest mosque in Herat; a much larger complex, the Mosque and Madressa of Gawhar Shad, built by the Timurids, was located in the northern part of the city. However, those architectural monuments were dynamited by officers of the British Indian Army in 1885, to prevent its use as a fortress if a Russian army tried to invade India.

History

editThe Masjid-i Jami of Herat is the city's first congregational mosque. It was built on a site where religious sites had been located for many centuries.[2] The first known building was a Zoroastrian temple converted into a mosque in the 7th century.[3] Afterward, it was enlarged by the Ghaznavids. In the second half of the 11th century, the Herat mosque was founded under the rule of the Khwarazmian dynasty. [4] It had a wooden roof and was of smaller dimensions than the following buildings. During an earthquake in 1102, it was almost completely destroyed but was rebuilt. Later it was ruined by a fire. Subsequently, the Ghurids constructed a mosque on the existing and adjacent plots.[2]

Ghurid rulers

editPlanning to expand their territory, the Ghurids seized power in Herat in 1175 CE. Herat is an important city because of its strategic position nearby the main commercial routes, from Mediterranean to India or China, and the resulting prosperity. At the end of the 12th century, Sultan Ghiyath al-Din Muhammed ibn San initiated the rebuilding of the city's main mosque in Herat.[2][5] For this purpose, he chose the existing plot of the burned mosque and additional land around it.[4] The land was located in the north-eastern, mainly administrative quarter of Herat and not directly in the center.[3] Scholars believe that this area was topographically elevated. Furthermore, it had a direct water supply from the main river joy-i-enjil for the fountain of the mosque. By building the mosque on an already known site, the Ghurids could demonstrate their architectural patronage, as well as political power.[5] Some sources also believe that the Sultan ordered the mosque to be built for Imam Fakhr-ul-Razi, a religious leader.[6]

After the Sultan died in 1203, he was buried in the mausoleum, a tomb building of his mosque. His son, Sultan Ghayath-ul-din Mahmood, continued the work on the mosque. By the time it was completed in 1210, his son had added a madrassa, a religious school. Stylistic analysis and historical inscriptions found during a renovation in 1964 prove that the building is attributed to the Ghurids.[2][4]

Kart rulers

editIn 1221, Genghis Khan forces conquered the province, and along with much of Herat, the mosque fell into ruin.[2][7] It wasn't until after 1245 that any rebuilding programs were undertaken.[3] This was under the rule of Shams al-Din Kart. [8] He was the king of the Kart dynasty, appointed by the Mongols as governor.[3] The construction of the mosque was not started until 1306.[1] A devastating earthquake in 1364 left the building almost destroyed. Afterward, some attempt was made to rebuild it.[1] A relic of the Kart dynasty is the bronze basin with a diameter of 1.74m. It was commissioned in 1375 by the last Kart ruler specifically for the mosque. This basin has survived all subsequent demolitions, except for a few scratches, and is still located in the mosque.[4][6][9]

Timurid Rulers

editAfter 1397, the Timurid rulers redirected Herat's growth towards the northern part of the city. This suburbanization and the building of a new congregational mosque in Gawhar Shad's Musalla marked the end of the Masjid-i Jami's patronage by a monarchy.[1] Under Shah Rukh (1405–1444), the mosque was repaired. The ground plan remained, but exterior aspects were changed. The inner courtyard facades were decorated with mosaic of glazed tiles, including the name of Shah Rukh. Also, a marble mihrab was added to the west of the mosque. A mihrab is a niche in the wall that indicates the direction of prayer to Mecca. [2][4]

Later, under the rule of Sultan Husayn Bayqara, his advisor Mir Ali-Shir Nava'i devoted himself to remodeling the mosque.[2][4] He made structural changes to the propositions, such as lowering the Ghoridic archway at the southeast corner. He also added lateral archways on both sides at the level of the roof. In addition, he ordered mosaic tiles with geometric patterns to be applied to further parts of the mosque. [10] The marble minbar with nine steps replaced the old wooden one. A minbar is a pulpit from which prayers are delivered.[4][6]

Mughal and Safavid Rulers

editThe mosque was later given another renovation under the Mughal Empire. During this period, Prince Khurram (Shah Jahan) was fighting for control of the region against the Uzbek tribes, which were controlled by the Safavids.[1] In this battle for Herat, the mosque, as well as the city of Herat itself, was considerably damaged.[2]

Afghan rulers

editUnder the Reign of different kings, the mosque was repaired multiple times. During the 18th century, the frontal facade of the main iwan from the Timurid period collapsed and had to be rebuilt. An iwan is a vaulted room or hall open on one side. Other than that, only repairs were made to maintain the existing form.[2][10]

20th Century

editAfter repair works in 1913, the mosque was extensively renovated in 1942/1943. The buildings directly adjacent to the mosque were destroyed in order to make the mosque a free-standing building. Among other things, a new east entrance with a high archway and two minarets was built. Minarets are towers from which people are called to prayer. The exterior walls were decorated with glazed tiles in the Timurid style.[2][11] For these works, a ceramic tile studio was established by UNESCO. This studio in the mosque also preserved all tile decorations and mosaics until 1979. The lettering was substituted by current calligraphers.

The follow-up was a more complete reconstruction from 1951 to 1973 involving structural changes.[5] The square dome of the mausoleum of the Ghurid time was widely destroyed. It was exchanged with an octagonal construction and integrated in the northern front. The wall to the east was also changed by an iwan with minarets on both sides. Also, the maqsura iwan, an enclosure reserved for the ruler, was made higher. The minarets next to it were increased to a height of 35m, and its porch was renewed. In addition, ten new minarets were added. [10] The facades in the courtyard were tiled with traditional mosaics in seven different colors. The floor was paved with light brown burnt bricks. Due to all these works, not much of the original Ghuridic plasterwork or Timurid decoration was visible. The mosque's madrassa was moved to the northeast and given its own entrance. The last significant change was the creation of a park in front of the mosque.[2][5]

During the Soviet-Afghan war (1979-1989), only limited demolition struck the mosque. This was the case despite the abuse of the minarets by Soviet soldiers and huge tanks moving around the area. In 1986 one minaret hit by a rocket crashed into the courtyard. It killed many people and caused damage to the eastern wing. The Soviets sent experts for reparation, but works have not been finished until 1995. Some more traces like bullet holes could be found. The Ghurid portal was not severely damaged. [12]

In 1992 the replacing of the stone plaster in the courtyard started, financed by private sponsoring. A pattern of wide strips of white marble alternating with narrow stripes of black marble was laid. Due to failing donations, it could not be finished until 1998. [2][12] During the Taliban's rule in Herat between 1996 and 2001, the entry to the mosque was banned for all non-muslims, including UN staff. [12]

21st Century

editIn 2002, all roofs of the mosque were renovated due to a problem with excessive humidity in the interior. During the renovation of the facades in 2004/05, parts of the old Ghurid decoration were found. These parts are exhibited in frames in the wall covering.[2] In 2012, some fifty Afghan traders promised funds for the renovation of the mosque.[13]

Architecture

editThe initial plan of the mosque by the Ghurids

editThe Ghurids built the entire mosque from brick.[4] The layout was a typical 4-iwan plan with an interior courtyard and a water basin. The qibla orientation towards the west was adhered to, although this deviates from the correct direction to Mecca by about 20°. The main iwan was covered by vaults. It formed an axial cross with the other three iwans on each side of the courtyard. They were intended as meeting and teaching places for smaller audiences.[2][5]

Mosque at present

editThe mosque complex is 180m long and 120m wide, covering an area of about 21,600 square meters. Besides the four large iwans, there are 460 domes, 444 pillars, and 12 minarets (17-36m height). [2] These elements are grouped around the central courtyard (82m by 60m).[2] [7] Pishtaqs, the gateways to the iwan, underline the spatial importance of the iwans. Together with the depth of the iwans, they provide a large surface for ornamentation.[7] A significant part of the present mosque is covered with glazed tiles in bright colors according to Timurid tradition.[2]

Decoration from the Ghurid period in the present mosque

editIn the southern and western iwan interior decorative elements of the Ghurid period are uncovered. They consist of stucco stamped with floral and geometric patterns. Stucco is a material for molding ornaments.[10][5] At the southeast corner of the mosque is the Ghurid portal. It has not served as a portal since unknown times. On both sides of the archway, Kufic inscriptions are displayed. This style of Arabic script is typical for the Ghurid period. The vertically placed bands of inscriptions are made of terracotta and worked into the base's mortar like a mosaic. On the front, they are glazed blue, contrasting with the light red brick tone of the background.[2][10] The sidewalls of the portal are decorated with geometrical brick mosaic, interspersed with blue glazed tile plugs.[5][14]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e "Great Mosque of Herat". Archnet.org. 19 August 2005. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Verfasser., Hansen, Erik. The Ghurid Portal of the Friday Mosque of Herat, Afghanistan : conservation of a historic monument. ISBN 978-87-7124-913-2. OCLC 959553318.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Frye, Richard N. (1948). "Two Timurid Monuments in Herat". Artibus Asiae. 11 (3): 206. doi:10.2307/3247934. ISSN 0004-3648.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Golombek, Lisa (1983). "The Resilience of the Friday Mosque: The Case of Herat". Muqarnas. 1: 95. doi:10.2307/1523073. ISSN 0732-2992.

- ^ a b c d e f g Patel, Alka (2007). "Architectural Cultures and Empire: The Ghurids in Northern India (ca. 1192–1210)". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. Vol.21: 35–60 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Etemadi, Guya (1953). "The General Mosque of Herat". Afghanistan. Vol. 8: 40–50.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Kazimee and McQuillan, Bashir and James (2002). "Living Traditions of the Afghan Courtyard and Aiwan". Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review. Vol. 13: 23–34 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Jamal, Nadia Eboo (2002). Surviving the Mongols: Nizārī Quhistānī and the Continuity of Ismaili Tradition in Persia. London: Tauris. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-86064-876-2.

- ^ Melikian, Souren (1973). "Le bassin extraordinaire qui donnait l'eau aux fidèles dans la mosque de Hérât". Connaissance des arts. Issue 252: 62–63.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d e Glatzer, Bernt (1980). "Das Mausoleum und die Moschee des Ghoriden Ghiyat ud-Din in Herat". Afghanistan Journal. Vol. 7: 6–34.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Stuckert, Ruedi (1980). "Der Baubestand der Masjid-al-Jami in Herat 1942/43". Afghanistan Journal. Vol. 7: 3–5.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Tirard-Collet, Olivier (1998). "After the War. The Condition of Historical Buildings and Monuments in Herat, Afghanistan". Iran. 36: 123. doi:10.2307/4299980. ISSN 0578-6967.

- ^ "Historical Herat Mosque Built over Ancient Zoroastrian Temples Being Renovated". The Gazette of Central Asia. Satrapia. 16 November 2012.

- ^ author., Broug, Eric,. Islamic geometric design. ISBN 978-0-500-51695-9. OCLC 1090514729.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)