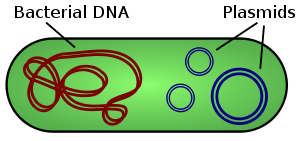

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; however, plasmids are sometimes present in archaea and eukaryotic organisms.[1][2] Plasmids often carry useful genes, such as for antibiotic resistance. While chromosomes are large and contain all the essential genetic information for living under normal conditions, plasmids are usually very small and contain additional genes for special circumstances.

Artificial plasmids are widely used as vectors in molecular cloning, serving to drive the replication of recombinant DNA sequences within host organisms. In the laboratory, plasmids may be introduced into a cell via transformation. Synthetic plasmids are available for procurement over the internet.[3][4][5]

Plasmids are considered replicons, units of DNA capable of replicating autonomously within a suitable host. However, plasmids, like viruses, are not generally classified as life.[6] Plasmids are transmitted from one bacterium to another (even of another species) mostly through conjugation.[7] This host-to-host transfer of genetic material is one mechanism of horizontal gene transfer, and plasmids are considered part of the mobilome. Unlike viruses, which encase their genetic material in a protective protein coat called a capsid, plasmids are "naked" DNA and do not encode genes necessary to encase the genetic material for transfer to a new host; however, some classes of plasmids encode the conjugative "sex" pilus necessary for their own transfer. Plasmids vary in size from 1 to over 400 kbp,[8] and the number of identical plasmids in a single cell can range from one up to thousands.

History

editThe term plasmid was introduced in 1952 by the American molecular biologist Joshua Lederberg to refer to "any extrachromosomal hereditary determinant."[9] The term's early usage included any bacterial genetic material that exists extrachromosomally for at least part of its replication cycle, but because that description includes bacterial viruses, the notion of plasmid was refined over time to refer to genetic elements that reproduce autonomously.[10] Later in 1968, it was decided that the term plasmid should be adopted as the term for extrachromosomal genetic element,[11] and to distinguish it from viruses, the definition was narrowed to genetic elements that exist exclusively or predominantly outside of the chromosome and can replicate autonomously.[10]

Properties and characteristics

editIn order for plasmids to replicate independently within a cell, they must possess a stretch of DNA that can act as an origin of replication. The self-replicating unit, in this case, the plasmid, is called a replicon. A typical bacterial replicon may consist of a number of elements, such as the gene for plasmid-specific replication initiation protein (Rep), repeating units called iterons, DnaA boxes, and an adjacent AT-rich region.[10] Smaller plasmids make use of the host replicative enzymes to make copies of themselves, while larger plasmids may carry genes specific for the replication of those plasmids. A few types of plasmids can also insert into the host chromosome, and these integrative plasmids are sometimes referred to as episomes in prokaryotes.[12]

Plasmids almost always carry at least one gene. Many of the genes carried by a plasmid are beneficial for the host cells, for example: enabling the host cell to survive in an environment that would otherwise be lethal or restrictive for growth. Some of these genes encode traits for antibiotic resistance or resistance to heavy metal, while others may produce virulence factors that enable a bacterium to colonize a host and overcome its defences or have specific metabolic functions that allow the bacterium to utilize a particular nutrient, including the ability to degrade recalcitrant or toxic organic compounds.[13] Plasmids can also provide bacteria with the ability to fix nitrogen. Some plasmids, however, have no observable effect on the phenotype of the host cell or its benefit to the host cells cannot be determined, and these plasmids are called cryptic plasmids.[14]

Naturally occurring plasmids vary greatly in their physical properties. Their size can range from very small mini-plasmids of less than 1-kilobase pairs (kbp) to very large megaplasmids of several megabase pairs (Mbp). At the upper end, little differs between a megaplasmid and a minichromosome. Plasmids are generally circular, but examples of linear plasmids are also known. These linear plasmids require specialized mechanisms to replicate their ends.[10]

Plasmids may be present in an individual cell in varying number, ranging from one to several hundreds. The normal number of copies of plasmid that may be found in a single cell is called the plasmid copy number, and is determined by how the replication initiation is regulated and the size of the molecule. Larger plasmids tend to have lower copy numbers.[12] Low-copy-number plasmids that exist only as one or a few copies in each bacterium are, upon cell division, in danger of being lost in one of the segregating bacteria. Such single-copy plasmids have systems that attempt to actively distribute a copy to both daughter cells. These systems, which include the parABS system and parMRC system, are often referred to as the partition system or partition function of a plasmid.[15]

Plasmids of linear form are unknown among phytopathogens with one exception, Rhodococcus fascians.[16]

Classifications and types

editPlasmids may be classified in a number of ways. Plasmids can be broadly classified into conjugative plasmids and non-conjugative plasmids. Conjugative plasmids contain a set of transfer genes which promote sexual conjugation between different cells.[12] In the complex process of conjugation, plasmids may be transferred from one bacterium to another via sex pili encoded by some of the transfer genes (see figure).[17] Non-conjugative plasmids are incapable of initiating conjugation, hence they can be transferred only with the assistance of conjugative plasmids. An intermediate class of plasmids are mobilizable, and carry only a subset of the genes required for transfer. They can parasitize a conjugative plasmid, transferring at high frequency only in its presence.[citation needed]

Plasmids can also be classified into incompatibility groups. A microbe can harbour different types of plasmids, but different plasmids can only exist in a single bacterial cell if they are compatible. If two plasmids are not compatible, one or the other will be rapidly lost from the cell. Different plasmids may therefore be assigned to different incompatibility groups depending on whether they can coexist together. Incompatible plasmids (belonging to the same incompatibility group) normally share the same replication or partition mechanisms and can thus not be kept together in a single cell.[18][19]

Another way to classify plasmids is by function. There are five main classes:

- Fertility F-plasmids, which contain tra genes. They are capable of conjugation and result in the expression of sex pili.

- Resistance (R) plasmids, which contain genes that provide resistance against antibiotics or antibacterial agents. Historically known as R-factors, before the nature of plasmids was understood.

- Col plasmids, which contain genes that code for bacteriocins, proteins that can kill other bacteria.

- Degradative plasmids, which enable the digestion of unusual substances, e.g. toluene and salicylic acid.

- Virulence plasmids, which turn the bacterium into a pathogen. e.g. Ti plasmid in Agrobacterium tumefaciens

Plasmids can belong to more than one of these functional groups.

RNA plasmids

editAlthough most plasmids are double-stranded DNA molecules, some consist of single-stranded DNA, or predominantly double-stranded RNA. RNA plasmids are non-infectious extrachromosomal linear RNA replicons, both encapsidated and unencapsidated, which have been found in fungi and various plants, from algae to land plants. In many cases, however, it may be difficult or impossible to clearly distinguish RNA plasmids from RNA viruses and other infectious RNAs.[20]

Chromids

editChromids are elements that exist at the boundary between a chromosome and a plasmid, found in about 10% of bacterial species sequenced by 2009. These elements carry core genes and have codon usage similar to the chromosome, yet use a plasmid-type replication mechanism such as the low copy number RepABC. As a result, they have been variously classified as minichromosomes or megaplasmids in the past.[21] In Vibrio, the bacterium synchronizes the replication of the chromosome and chromid by a conserved genome size ratio.[22]

Vectors

editArtificially constructed plasmids may be used as vectors in genetic engineering. These plasmids serve as important tools in genetics and biotechnology labs, where they are commonly used to clone and amplify (make many copies of) or express particular genes.[23] A wide variety of plasmids are commercially available for such uses. The gene to be replicated is normally inserted into a plasmid that typically contains a number of features for their use. These include a gene that confers resistance to particular antibiotics (ampicillin is most frequently used for bacterial strains), an origin of replication to allow the bacterial cells to replicate the plasmid DNA, and a suitable site for cloning (referred to as a multiple cloning site).

DNA structural instability can be defined as a series of spontaneous events that culminate in an unforeseen rearrangement, loss, or gain of genetic material. Such events are frequently triggered by the transposition of mobile elements or by the presence of unstable elements such as non-canonical (non-B) structures. Accessory regions pertaining to the bacterial backbone may engage in a wide range of structural instability phenomena. Well-known catalysts of genetic instability include direct, inverted, and tandem repeats, which are known to be conspicuous in a large number of commercially available cloning and expression vectors.[24] Insertion sequences can also severely impact plasmid function and yield, by leading to deletions and rearrangements, activation, down-regulation or inactivation of neighboring gene expression.[25] Therefore, the reduction or complete elimination of extraneous noncoding backbone sequences would pointedly reduce the propensity for such events to take place, and consequently, the overall recombinogenic potential of the plasmid.[26][27]

Cloning

editPlasmids are the most-commonly used bacterial cloning vectors.[28] These cloning vectors contain a site that allows DNA fragments to be inserted, for example a multiple cloning site or polylinker which has several commonly used restriction sites to which DNA fragments may be ligated. After the gene of interest is inserted, the plasmids are introduced into bacteria by a process called transformation. These plasmids contain a selectable marker, usually an antibiotic resistance gene, which confers on the bacteria an ability to survive and proliferate in a selective growth medium containing the particular antibiotics. The cells after transformation are exposed to the selective media, and only cells containing the plasmid may survive. In this way, the antibiotics act as a filter to select only the bacteria containing the plasmid DNA. The vector may also contain other marker genes or reporter genes to facilitate selection of plasmids with cloned inserts. Bacteria containing the plasmid can then be grown in large amounts, harvested, and the plasmid of interest may then be isolated using various methods of plasmid preparation.

A plasmid cloning vector is typically used to clone DNA fragments of up to 15 kbp.[29] To clone longer lengths of DNA, lambda phage with lysogeny genes deleted, cosmids, bacterial artificial chromosomes, or yeast artificial chromosomes are used.

Protein production

editAnother major use of plasmids is to make large amounts of proteins. In this case, researchers grow bacteria containing a plasmid harboring the gene of interest. Just as the bacterium produces proteins to confer its antibiotic resistance, it can also be induced to produce large amounts of proteins from the inserted gene. This is a cheap and easy way of mass-producing the protein the gene codes for, for example, insulin.

Gene therapy

editPlasmids may also be used for gene transfer as a potential treatment in gene therapy so that it may express the protein that is lacking in the cells. Some forms of gene therapy require the insertion of therapeutic genes at pre-selected chromosomal target sites within the human genome. Plasmid vectors are one of many approaches that could be used for this purpose. Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) offer a way to cause a site-specific double-strand break to the DNA genome and cause homologous recombination. Plasmids encoding ZFN could help deliver a therapeutic gene to a specific site so that cell damage, cancer-causing mutations, or an immune response is avoided.[30]

Disease models

editPlasmids were historically used to genetically engineer the embryonic stem cells of rats to create rat genetic disease models. The limited efficiency of plasmid-based techniques precluded their use in the creation of more accurate human cell models. However, developments in adeno-associated virus recombination techniques, and zinc finger nucleases, have enabled the creation of a new generation of isogenic human disease models.

Episomes

editThe term episome was introduced by François Jacob and Élie Wollman in 1958 to refer to extra-chromosomal genetic material that may replicate autonomously or become integrated into the chromosome.[31][32] Since the term was introduced, however, its use has changed, as plasmid has become the preferred term for autonomously replicating extrachromosomal DNA. At a 1968 symposium in London some participants suggested that the term episome be abandoned, although others continued to use the term with a shift in meaning.[33][34]

Today, some authors use episome in the context of prokaryotes to refer to a plasmid that is capable of integrating into the chromosome. The integrative plasmids may be replicated and stably maintained in a cell through multiple generations, but at some stage, they will exist as an independent plasmid molecule.[35] In the context of eukaryotes, the term episome is used to mean a non-integrated extrachromosomal closed circular DNA molecule that may be replicated in the nucleus.[36][37] Viruses are the most common examples of this, such as herpesviruses, adenoviruses, and polyomaviruses, but some are plasmids. Other examples include aberrant chromosomal fragments, such as double minute chromosomes, that can arise during artificial gene amplifications or in pathologic processes (e.g., cancer cell transformation). Episomes in eukaryotes behave similarly to plasmids in prokaryotes in that the DNA is stably maintained and replicated with the host cell. Cytoplasmic viral episomes (as in poxvirus infections) can also occur. Some episomes, such as herpesviruses, replicate in a rolling circle mechanism, similar to bacteriophages (bacterial phage viruses). Others replicate through a bidirectional replication mechanism (Theta type plasmids). In either case, episomes remain physically separate from host cell chromosomes. Several cancer viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, are maintained as latent, chromosomally distinct episomes in cancer cells, where the viruses express oncogenes that promote cancer cell proliferation. In cancers, these episomes passively replicate together with host chromosomes when the cell divides. When these viral episomes initiate lytic replication to generate multiple virus particles, they generally activate cellular innate immunity defense mechanisms that kill the host cell.

Plasmid maintenance

editSome plasmids or microbial hosts include an addiction system or postsegregational killing system (PSK), such as the hok/sok (host killing/suppressor of killing) system of plasmid R1 in Escherichia coli.[38] This variant produces both a long-lived poison and a short-lived antidote. Several types of plasmid addiction systems (toxin/ antitoxin, metabolism-based, ORT systems) were described in the literature[39] and used in biotechnical (fermentation) or biomedical (vaccine therapy) applications. Daughter cells that retain a copy of the plasmid survive, while a daughter cell that fails to inherit the plasmid dies or suffers a reduced growth-rate because of the lingering poison from the parent cell. Finally, the overall productivity could be enhanced.

In contrast, plasmids used in biotechnology, such as pUC18, pBR322 and derived vectors, hardly ever contain toxin-antitoxin addiction systems, and therefore need to be kept under antibiotic pressure to avoid plasmid loss.

Plasmids in nature

editYeast plasmids

editYeasts naturally harbour various plasmids. Notable among them are 2 μm plasmids—small circular plasmids often used for genetic engineering of yeast—and linear pGKL plasmids from Kluyveromyces lactis, that are responsible for killer phenotypes.[40]

Other types of plasmids are often related to yeast cloning vectors that include:

- Yeast integrative plasmid (YIp), yeast vectors that rely on integration into the host chromosome for survival and replication, and are usually used when studying the functionality of a solo gene or when the gene is toxic. Also connected with the gene URA3, that codes an enzyme related to the biosynthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides (T, C);

- Yeast Replicative Plasmid (YRp), which transport a sequence of chromosomal DNA that includes an origin of replication. These plasmids are less stable, as they can be lost during budding.

Plant mitochondrial plasmids

editThe mitochondria of many higher plants contain self-replicating, extra-chromosomal linear or circular DNA molecules which have been considered to be plasmids. These can range from 0.7 kb to 20 kb in size. The plasmids have been generally classified into two categories- circular and linear.[41] Circular plasmids have been isolated and found in many different plants, with those in Vicia faba and Chenopodium album being the most studied and whose mechanism of replication is known. The circular plasmids can replicate using the θ model of replication (as in Vicia faba) and through rolling circle replication (as in C.album).[42] Linear plasmids have been identified in some plant species such as Beta vulgaris, Brassica napus, Zea mays, etc. but are rarer than their circular counterparts.

The function and origin of these plasmids remains largely unknown. It has been suggested that the circular plasmids share a common ancestor, some genes in the mitochondrial plasmid have counterparts in the nuclear DNA suggesting inter-compartment exchange. Meanwhile, the linear plasmids share structural similarities such as invertrons with viral DNA and fungal plasmids, like fungal plasmids they also have low GC content, these observations have led to some hypothesizing that these linear plasmids have viral origins, or have ended up in plant mitochondria through horizontal gene transfer from pathogenic fungi.[41][43]

Study of plasmids

editPlasmid DNA extraction

editPlasmids are often used to purify a specific sequence, since they can easily be purified away from the rest of the genome. For their use as vectors, and for molecular cloning, plasmids often need to be isolated.

There are several methods to isolate plasmid DNA from bacteria, ranging from the miniprep to the maxiprep or bulkprep.[23] The former can be used to quickly find out whether the plasmid is correct in any of several bacterial clones. The yield is a small amount of impure plasmid DNA, which is sufficient for analysis by restriction digest and for some cloning techniques.

In the latter, much larger volumes of bacterial suspension are grown from which a maxi-prep can be performed. In essence, this is a scaled-up miniprep followed by additional purification. This results in relatively large amounts (several hundred micrograms) of very pure plasmid DNA.

Many commercial kits have been created to perform plasmid extraction at various scales, purity, and levels of automation.

Conformations

editPlasmid DNA may appear in one of five conformations, which (for a given size) run at different speeds in a gel during electrophoresis. The conformations are listed below in order of electrophoretic mobility (speed for a given applied voltage) from slowest to fastest:

- Nicked open-circular DNA has one strand cut.

- Relaxed circular DNA is fully intact with both strands uncut but has been enzymatically relaxed (supercoils removed). This can be modeled by letting a twisted extension cord unwind and relax and then plugging it into itself.

- Linear DNA has free ends, either because both strands have been cut or because the DNA was linear in vivo. This can be modeled with an electrical extension cord that is not plugged into itself.

- Supercoiled (or covalently closed-circular) DNA is fully intact with both strands uncut, and with an integral twist, resulting in a compact form. This can be modeled by twisting an extension cord and then plugging it into itself.

- Supercoiled denatured DNA is similar to supercoiled DNA, but has unpaired regions that make it slightly less compact; this can result from excessive alkalinity during plasmid preparation.

The rate of migration for small linear fragments is directly proportional to the voltage applied at low voltages. At higher voltages, larger fragments migrate at continuously increasing yet different rates. Thus, the resolution of a gel decreases with increased voltage.

At a specified, low voltage, the migration rate of small linear DNA fragments is a function of their length. Large linear fragments (over 20 kb or so) migrate at a certain fixed rate regardless of length. This is because the molecules 'respirate', with the bulk of the molecule following the leading end through the gel matrix. Restriction digests are frequently used to analyse purified plasmids. These enzymes specifically break the DNA at certain short sequences. The resulting linear fragments form 'bands' after gel electrophoresis. It is possible to purify certain fragments by cutting the bands out of the gel and dissolving the gel to release the DNA fragments.

Because of its tight conformation, supercoiled DNA migrates faster through a gel than linear or open-circular DNA.

Software for bioinformatics and design

editThe use of plasmids as a technique in molecular biology is supported by bioinformatics software. These programs record the DNA sequence of plasmid vectors, help to predict cut sites of restriction enzymes, and to plan manipulations. Examples of software packages that handle plasmid maps are ApE, Clone Manager, GeneConstructionKit, Geneious, Genome Compiler, LabGenius, Lasergene, MacVector, pDraw32, Serial Cloner, VectorFriends, Vector NTI, and WebDSV. These pieces of software help conduct entire experiments in silico before doing wet experiments.[44]

Plasmid collections

editMany plasmids have been created over the years and researchers have given out plasmids to plasmid databases such as the non-profit organisations Addgene and BCCM/LMBP. One can find and request plasmids from those databases for research. Researchers also often upload plasmid sequences to the NCBI database, from which sequences of specific plasmids can be retrieved.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Esser K, Kück U, Lang-Hinrichs C, Lemke P, Osiewacz HD, Stahl U, Tudzynski P (1986). Plasmids of Eukaryotes: fundamentals and Applications. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-15798-4.

- ^ Wickner RB, Hinnebusch A, Lambowitz AM, Gunsalus IC, Hollaender A, eds. (1987). "Mitochondrial and Chloroplast Plasmids". Extrachromosomal Elements in Lower Eukaryotes. Boston, MA: Springer US. pp. 81–146. ISBN 978-1-4684-5251-8.

- ^ "GenBrick Gene Synthesis - Long DNA Sequences | GenScript".

- ^ "Gene synthesis | IDT". Integrated DNA Technologies.

- ^ "Invitrogen GeneArt Gene Synthesis".

- ^ Sinkovics J, Horvath J, Horak A (1998). "The origin and evolution of viruses (a review)". Acta Microbiologica et Immunologica Hungarica. 45 (3–4): 349–90. PMID 9873943.

- ^ Smillie C, Garcillán-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EP, de la Cruz F (September 2010). "Mobility of plasmids". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 74 (3): 434–52. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00020-10. PMC 2937521. PMID 20805406.

- ^ Thomas CM, Summers D (2008). "Bacterial Plasmids". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0000468.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- ^ Lederberg J (October 1952). "Cell genetics and hereditary symbiosis". Physiological Reviews. 32 (4): 403–30. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.458.985. doi:10.1152/physrev.1952.32.4.403. PMID 13003535.

- ^ a b c d Hayes F (2003). "Chapter 1 – The Function and Organization of Plasmids". In Casali N, Presto A (eds.). E. Coli Plasmid Vectors: Methods and Applications. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 235. Humana Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-58829-151-6.

- ^ Falkow S. "Microbial Genomics: Standing on the Shoulders of Giants". Microbiology Society.

- ^ a b c Brown TA (2010). "Chapter 2 – Vectors for Gene Cloning: Plasmids and Bacteriophages". Gene Cloning and DNA Analysis: An Introduction (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405181730.

- ^ Smyth C, Leigh RJ, Delaney S, Murphy RA, Walsh F (2022). "Shooting hoops: globetrotting plasmids spreading more than just antimicrobial resistance genes across One Health". Microbial Genomics. 8 (8): 1–10. doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000858. PMC 9484753. PMID 35960657.

- ^ Summers DK (1996). "Chapter 1 – The Function and Organization of Plasmids". The Biology of Plasmids (First ed.). Osney, Oxford OX: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-632-03436-9.

- ^ Dmowski, Michał; Jagura-Burdzy, Grazyna (2013). "Active stable maintenance functions in low copy-number plasmids of Gram-positive bacteria I. Partition systems". Polish Journal of Microbiology. 62 (1): 3–16. doi:10.33073/pjm-2013-001. ISSN 1733-1331. PMID 23829072.

- ^ Stes, Elisabeth; Vandeputte, Olivier; Jaziri, Mondher; Holsters, Marcelle; Vereecke, Danny (2011). "A Successful Bacterial Coup d'État: How Rhodococcus fascians Redirects Plant Development". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 49 (1). Annual Reviews: 69–86. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-072910-095217. ISSN 0066-4286. PMID 21495844.

- ^ Clark DP, Pazdernik NJ (2012). Molecular Biology (2nd ed.). Academic Cell. p. 795. ISBN 978-0123785947.

- ^ Radnedge L, Richards H (January 1999). "Chapter 2: The Development of Plasmid Vectors.". In Smith MC, Sockett RE (eds.). Genetic Methods for Diverse Prokaryotes. Methods in Microbiology. Vol. 29. Academic Press. pp. 51-96 (75-77). ISBN 978-0-12-652340-9.

- ^ "Plasmids 101: Origin of Replication". addgene.org.

- ^ Brown GG, Finnegan PM (January 1989). "RNA plasmids". International Review of Cytology. 117: 1–56. doi:10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61333-9. ISBN 978-0-12-364517-3. PMID 2684889.

- ^ Harrison, PW; Lower, RP; Kim, NK; Young, JP (April 2010). "Introducing the bacterial 'chromid': not a chromosome, not a plasmid". Trends in Microbiology. 18 (4): 141–8. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.010. PMID 20080407.

- ^ Bruhn, Matthias; Schindler, Daniel; Kemter, Franziska S.; Wiley, Michael R.; Chase, Kitty; Koroleva, Galina I.; Palacios, Gustavo; Sozhamannan, Shanmuga; Waldminghaus, Torsten (30 November 2018). "Functionality of Two Origins of Replication in Vibrio cholerae Strains With a Single Chromosome". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 2932. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02932. PMC 6284228. PMID 30559732.

- ^ a b Russell DW, Sambrook J (2001). Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- ^ Oliveira PH, Prather KJ, Prazeres DM, Monteiro GA (August 2010). "Analysis of DNA repeats in bacterial plasmids reveals the potential for recurrent instability events". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 87 (6): 2157–67. doi:10.1007/s00253-010-2671-7. PMID 20496146. S2CID 19780633.

- ^ Gonçalves GA, Oliveira PH, Gomes AG, Prather KL, Lewis LA, Prazeres DM, Monteiro GA (August 2014). "Evidence that the insertion events of IS2 transposition are biased towards abrupt compositional shifts in target DNA and modulated by a diverse set of culture parameters" (PDF). Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 98 (15): 6609–19. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-5695-6. hdl:1721.1/104375. PMID 24769900. S2CID 9826684.

- ^ Oliveira PH, Mairhofer J (September 2013). "Marker-free plasmids for biotechnological applications – implications and perspectives". Trends in Biotechnology. 31 (9): 539–47. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2013.06.001. PMID 23830144.

- ^ Oliveira PH, Prather KJ, Prazeres DM, Monteiro GA (September 2009). "Structural instability of plasmid biopharmaceuticals: challenges and implications". Trends in Biotechnology. 27 (9): 503–11. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.06.004. PMID 19656584.

- ^ Geoghegan T (2002). "Molecular Applications". In Streips UN, Yasbin RE (eds.). Modern Microbial Genetics (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 248. ISBN 978-0471386650.

- ^ Preston A (2003). "Chapter 2 – Choosing a Cloning Vector". In Casali N, Preston A (eds.). E. Coli Plasmid Vectors: Methods and Applications. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 235. Humana Press. pp. 19–26. ISBN 978-1-58829-151-6.

- ^ Kandavelou K, Chandrasegaran S (2008). "Plasmids for Gene Therapy". Plasmids: Current Research and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-35-6.

- ^ Morange M (December 2009). "What history tells us XIX. The notion of the episome" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 34 (6): 845–48. doi:10.1007/s12038-009-0098-z. PMID 20093737. S2CID 11367145.

- ^ Jacob F, Wollman EL (1958), "Les épisomes, elements génétiques ajoutés", Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris, 247 (1): 154–56, PMID 13561654

- ^ Hayes W (1969). "What are episomes and plasmids?". In Wolstenholme GE, O'Connor M (eds.). Bacterial Episomes and Plasmids. CIBA Foundation Symposium. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0700014057.

- ^ Wolstenholme GE, O'Connor M, eds. (1969). Bacterial Episomes and Plasmids. CIBA Foundation Symposium. pp. 244–45. ISBN 978-0700014057.

- ^ Brown TA (2011). Introduction to Genetics: A Molecular Approach. Garland Science. p. 238. ISBN 978-0815365099.

- ^ Van Craenenbroeck K, Vanhoenacker P, Haegeman G (September 2000). "Episomal vectors for gene expression in mammalian cells". European Journal of Biochemistry. 267 (18): 5665–78. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01645.x. PMID 10971576.

- ^ Colosimo A, Goncz KK, Holmes AR, Kunzelmann K, Novelli G, Malone RW, Bennett MJ, Gruenert DC (August 2000). "Transfer and expression of foreign genes in mammalian cells" (PDF). BioTechniques. 29 (2): 314–18, 320–22, 324 passim. doi:10.2144/00292rv01. PMID 10948433. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

- ^ Gerdes K, Rasmussen PB, Molin S (May 1986). "Unique type of plasmid maintenance function: postsegregational killing of plasmid-free cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 83 (10): 3116–20. Bibcode:1986PNAS...83.3116G. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.10.3116. PMC 323463. PMID 3517851.

- ^ Kroll J, Klinter S, Schneider C, Voss I, Steinbüchel A (November 2010). "Plasmid addiction systems: perspectives and applications in biotechnology". Microbial Biotechnology. 3 (6): 634–57. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00170.x. PMC 3815339. PMID 21255361.

- ^ Gunge N, Murata K, Sakaguchi K (July 1982). "Transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with linear DNA killer plasmids from Kluyveromyces lactis". Journal of Bacteriology. 151 (1): 462–64. doi:10.1128/JB.151.1.462-464.1982. PMC 220260. PMID 7045080.

- ^ a b Gualberto, José M.; Mileshina, Daria; Wallet, Clémentine; Niazi, Adnan Khan; Weber-Lotfi, Frédérique; Dietrich, André (May 2014). "The plant mitochondrial genome: Dynamics and maintenance". Biochimie. 100: 107–120. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2013.09.016. PMID 24075874.

- ^ Backert, Meißner, Börner (1 February 1997). "Unique Features of the Mitochondrial Rolling Circle-Plasmid mp1 from the Higher Plant Chenopodium Album (L.)". Nucleic Acids Research. 25 (3): 582–589. doi:10.1093/nar/25.3.582. PMC 146482. PMID 9016599.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Handa, Hirokazu (January 2008). "Linear plasmids in plant mitochondria: Peaceful coexistences or malicious invasions?". Mitochondrion. 8 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2007.10.002. PMID 18326073.

- ^ "Vector NTI feedback video". The DNA Lab.

Further reading

editGeneral works

edit- Klein DW, Prescott LM, Harley J (1999). Microbiology. Boston: WCB/McGraw-Hill.

- Moat AG, Foster JW, Spector MP (2002). Microbial Physiology. Wiley-Liss. ISBN 978-0-471-39483-9.

- Smith CU (2002). "Chapter 5: Manipulating Biomolecules". Elements of Molecular Neurobiology (3rd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, England: Wiley. pp. 101–11. ISBN 978-0-470-85717-5.

Episomes

edit- Piechaczek C, Fetzer C, Baiker A, Bode J, Lipps HJ (January 1999). "A vector based on the SV40 origin of replication and chromosomal S/MARs replicates episomally in CHO cells". Nucleic Acids Research. 27 (2): 426–28. doi:10.1093/nar/27.2.426. PMC 148196. PMID 9862961.

- Bode J, Fetzer CP, Nehlsen K, Scinteie M, Hinrichsen BH, Baiker A, et al. (January 2001). "The Hitchhiking principle: Optimizing episomal vectors for the use in gene therapy and biotechnology" (PDF). Gene Therapy and Molecular Biology. 6: 33–46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009.

- Nehlsen K, Broll S, Bode J (2006). "Replicating minicircles: Generation of nonviral episomes for the efficient modification of dividing cells" (PDF). Gene Ther Mol Biol. 10: 233–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009.

- Ehrhardt A, Haase R, Schepers A, Deutsch MJ, Lipps HJ, Baiker A (June 2008). "Episomal vectors for gene therapy". Current Gene Therapy. 8 (3): 147–61. doi:10.2174/156652308784746440. PMID 18537590. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011.

- Argyros O, Wong SP, Niceta M, Waddington SN, Howe SJ, Coutelle C, Miller AD, Harbottle RP (December 2008). "Persistent episomal transgene expression in liver following delivery of a scaffold/matrix attachment region containing non-viral vector". Gene Therapy. 15 (24): 1593–605. doi:10.1038/gt.2008.113. PMID 18633447.

- Wong SP, Argyros O, Coutelle C, Harbottle RP (August 2009). "Strategies for the episomal modification of cells". Current Opinion in Molecular Therapeutics. 11 (4): 433–41. PMID 19649988. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011.

- Haase R, Argyros O, Wong SP, Harbottle RP, Lipps HJ, Ogris M, Magnusson T, Vizoso Pinto MG, Haas J, Baiker A (March 2010). "pEPito: a significantly improved non-viral episomal expression vector for mammalian cells". BMC Biotechnology. 10: 20. doi:10.1186/1472-6750-10-20. PMC 2847955. PMID 20230618.