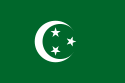

The Republic of Egypt was a state created in 1953 under the rule of Mohammed Naguib following the Egyptian revolution of 1952 in which the Kingdom of Egypt's Muhammad Ali dynasty came to an end. It was superseded in 1958 with the creation of the United Arab Republic.

Republic of Egypt | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953–1958 | |||||||||||

Coat of arms

(1953–1958) | |||||||||||

| Anthem: Salam Affandina | |||||||||||

Republic of Egypt | |||||||||||

| Capital | Cairo | ||||||||||

| Largest city | Capital | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Arabic | ||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | Egyptian Arabic | ||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Egyptian | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic under a Nasserist military dictatorship[1] | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1953–1954 | Mohamed Naguib | ||||||||||

• 1954–1958 | Gamal Abdel Nasser | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1953–1954 | Mohamed Naguib | ||||||||||

• 1954 | Gamal Abdel Nasser | ||||||||||

• 1954 | Mohamed Naguib | ||||||||||

• 1954–1958 | Gamal Abdel Nasser | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Arab Cold War | ||||||||||

| 18 June 1953 | |||||||||||

| 23 July 1952 | |||||||||||

| 29 October 1956 – 7 November 1956 | |||||||||||

| 22 February 1958 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• Total | 1,010,408 km2 (390,121 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1953 | 22,028,134 | ||||||||||

• 1955 | 23,223,124 | ||||||||||

• 1958 | 25,209,459 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Egyptian Pound | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | EG | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Egypt Palestine (Gaza Strip) Sudan (Until 1956) South Sudan (Until 1956) | ||||||||||

The territory of the state compromised modern day Egypt as well as the Gaza Strip, governed by the All-Palestine Protectorate. The territory also included modern day Sudan and South Sudan until 1956 when the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Condominium was abolished, granting the Republic of the Sudan independence.

The Revolution

editThe Free Officers

editThe Republic of Egypt was created following the 1952 Egyptian revolution led by the Free Officers, a group of army officers who wanted to overthrow King Farouk and abolish the Muhammad Ali dynasty in Egypt which was led by Mohamed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser.[2]

The Free Officers's goals were to abolish the Kingdom of Egypt, to establish a republic, end the British occupation of Egypt including the Suez Canal, and to secure the independence of Sudan from the British, who governed it as Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[3] The revolutionary government adopted a staunchly nationalist, anti-imperialist agenda, which came to be expressed chiefly through Arab nationalism, and international non-alignment.

The revolution was faced with immediate threats from Western imperial powers, particularly the United Kingdom, which had occupied Egypt since 1882, and France, both of whom were wary of rising nationalist sentiment in territories under their control throughout Africa and the Arab world. The ongoing state of war with Israel also posed a serious challenge, as the Free Officers increased Egypt's already strong support of the Palestinians. These two issues conflated four years after the revolution when Egypt was invaded by Britain, France, and Israel in the Suez Crisis of 1956. Despite enormous military losses,[4] the war was seen as a political victory for Egypt, especially as it left the Suez Canal in uncontested Egyptian control for the first time since 1875, erasing what was seen as a mark of national humiliation. This strengthened the appeal of the revolution in other Arab and African countries.[5]

The coup

editWhile the Free Officers planned to overthrow the monarchy on 2–3 August, they decided to make their move earlier after their official leader, Naguib, gained knowledge, leaked from the Egyptian cabinet on 19 July, that King Farouk acquired a list of the dissenting officers and was set to arrest them. The officers thus decided to launch a preemptive strike and after finalizing their plans in meeting at the home of Khaled Mohieddin, they began their coup on the night of 22 July. Mohieddin stayed in his home and Anwar Sadat went to the cinema.[6]

Meanwhile, the chairman of the Free Officers, Nasser, contacted the Muslim Brotherhood and the communist Democratic Movement for National Liberation to assure their support. On the morning of 23 July, he and Abdel Hakim Amer left Mohieddin's home in civilian clothes and drove around Cairo in Nasser's automobile to collect men to arrest key royalist commanders before they reached their barracks and gain control over their soldiers. As they approached the el-Qoba Bridge, an artillery unit led by Youssef Seddik met with them before he led his battalion to take control the Military General Headquarters to arrest the royalist army chief of staff, Hussein Sirri Amer and all the other commanders who were present in the building. At 6:00 am the Free Officers air force units began patrolling Cairo's skies.[7]

By 25 July 1952, the army had occupied Alexandria, where Farouk was in residence at the Montaza Palace. Terrified, Farouk abandoned Montaza and fled to Ras Al-Teen Palace on the waterfront. Naguib ordered the captain of Farouk's yacht, al-Mahrusa, not to sail without orders from the Egyptian Army.[citation needed]

Debate broke out among the Free Officers concerning the fate of the deposed king. While some (including Naguib and Nasser) thought that the best course of action was to send him into exile, others argued that he should be put on trial or executed. Finally, the order came for Farouk to abdicate in favor of his son, the crown prince Ahmed Fuad – who was acceded to the throne as King Fuad II[8] – and a three-man Regency Council was appointed. The former king's departure into exile came on Saturday, 26 July 1952 and at 6 o'clock that evening he set sail for Italy with protection from the Egyptian Army. On 28 July 1953, Naguib became the first President of Egypt, which marked the beginning of modern Egyptian governance.[9]

History

editNaguib presidency (1953–1954)

editFollowing the 1952 revolution by the Free Officers movement, the rule of Egypt passed to military hands and all political parties were banned. On 18 June 1953, the Egyptian Republic of Egypt was declared, with Naguib as the first president of the Republic, serving in that capacity for a little under one and a half years until he was placed under house arrest by Nasser after a brief power struggle.[10]

Nasser presidency (1954–1958)

editNaguib was forced to resign in 1954 by Nasser – a pan-Arabist and the main architect of the 1952 movement – and was later put under house arrest. After Naguib's resignation, the position of President was vacant until the election of Nasser in 1956.

After the three-year transition period ended with Nasser's official assumption of power, his domestic and independent foreign policies increasingly collided with the regional interests of the UK and France. The latter condemned his strong support for Algerian independence, and the UK's Eden government was agitated by Nasser's campaign against the Baghdad Pact.[11] In addition, Nasser's adherence to neutralism regarding the Cold War, recognition of Maoist China, and arms deal with the Eastern Bloc alienated the United States. On 19 July 1956, the US and UK abruptly withdrew their offer to finance construction of the Aswan Dam,[11] citing concerns that Egypt's economy would be overwhelmed by the project.[12]

In October 1954, Egypt and Britain agreed to abolish the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899 and grant Sudan independence to become the Republic of the Sudan; the agreement came into force on 1 January 1956.

Nasser assumed power as president in June 1956. British forces completed their withdrawal from the occupied Suez Canal Zone on 13 June 1956. On 26 July 1956, Nasser gave a speech in Alexandria announcing the nationalization of the Suez Canal Company as a means to fund the Aswan Dam project in light of the British–American withdrawal.[13] In the speech, he denounced British imperialism in Egypt and British control over the company's profits, and upheld that the Egyptians had a right to sovereignty over the waterway, especially since "120,000 Egyptians had died building it".[13] He nationalized the Suez Canal the same day of the speech; his hostile approach towards Israel and economic nationalism prompted the beginning of the Second Arab-Israeli War (Suez Crisis), in which Israel (with support from France and the United Kingdom) occupied the Sinai Peninsula and the Sues Canal. The war came to an end because of US and USSR diplomatic intervention,[14] and the status quo was restored. The motion was technically in breach of the international agreement he had signed with the UK on 19 October 1954,[15] although he ensured that all existing stockholders would be paid off.[16]

The nationalization announcement was greeted very emotionally by the audience and, throughout the Arab world, thousands entered the streets shouting slogans of support.[17] US ambassador Henry A. Byroade stated, "I cannot overemphasize [the] popularity of the Canal Company nationalization within Egypt, even among Nasser's enemies."[15] Egyptian political scientist Mahmoud Hamad wrote that, prior to 1956, Nasser had consolidated control over Egypt's military and civilian bureaucracies, but it was only after the canal's nationalization that he gained near-total popular legitimacy and firmly established himself as the "charismatic leader" and "spokesman for the masses not only in Egypt, but all over the Third World".[18] According to Aburish, this was Nasser's largest pan-Arab triumph at the time and "soon his pictures were to be found in the tents of Yemen, the souks of Marrakesh, and the posh villas of Syria".[17] The official reason given for the nationalization was that funds from the canal would be used for the construction of the Aswan Dam.[15] That same day, Egypt closed the canal to Israeli shipping.[16]

The nationalization surprised Britain and its Commonwealth. There had been no discussion of the canal at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in London in late June and early July. Egypt's action, however, threatened British economic and military interests in the region. Prime Minister Eden was under immense domestic pressure from Conservative MPs who drew direct comparisons between the events of 1956 and those of the Munich Agreement in 1938. Since the US government did not support the British protests, the British government decided in favour of military intervention against Egypt to avoid the complete collapse of British prestige in the region.[citation needed]

Eden was hosting a dinner for King Faisal II of Iraq and his Prime Minister, Nuri al-Said, when he learned the canal had been nationalized. They both unequivocally advised Eden to "hit Nasser hard, hit him soon, and hit him by yourself" – a stance shared by the vast majority of the British people in subsequent weeks. "There is a lot of humbug about Suez," Guy Millard, one of Eden's private secretaries, later recorded. "People forget that the policy at the time was extremely popular." Opposition leader Hugh Gaitskell was also at the dinner. He immediately agreed that military action might be inevitable, but warned Eden would have to keep the Americans closely informed. After a session of the House of Commons expressed anger against the Egyptian action on 27 July, Eden justifiably believed that Parliament would support him; Gaitskell spoke for his party when he called the nationalization a "high-handed and totally unjustifiable step". When Eden made a ministerial broadcast on the nationalization, his political party declined its right to reply.[19]

Nasser assumed power as president in June 1956. British forces completed their withdrawal from the occupied Suez Canal Zone on 13 June 1956. He nationalized the Suez Canal on 26 July 1956; his hostile approach towards Israel and economic nationalism prompted the beginning of the Second Arab-Israeli War (Suez Crisis), in which Israel (with support from France and the United Kingdom) occupied the Sinai Peninsula and the canal. The war came to an end because of US and USSR diplomatic intervention[14] and the status quo was restored.[20]

Suez Crisis (1956)

editOn 29 October, Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai. Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to cease fire, which was ignored. On 5 November, Britain and France landed paratroopers along the Suez Canal. While the Egyptian forces were defeated, they had blocked the Suez Canal to all shipping. It later became clear that Israel, France, and Britain had conspired to plan out the invasion. The three allies had attained a number of their military objectives, but the Suez Canal was useless. Heavy political pressure from the United States and the USSR led to a withdrawal. US President Dwight D. Eisenhower had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the US government's pound sterling bonds. Historians conclude the Crisis "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers".[14][21]

On 29 October, Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai. Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to cease fire, which was ignored. The aims were to regain Western control of the Suez Canal and to remove Egyptian president Nasser, who had just nationalized the Suez Canal.[22] On 5 November, Britain and France landed paratroopers along the Suez Canal. While the Egyptian forces were defeated, they had blocked the Suez Canal to all shipping.[23][24]

Operation Kadesh received its name from ancient Kadesh, located in the northern Sinai and mentioned several times in the Hebrew Pentateuch. Israeli military planning for this operation in the Sinai hinged on four main military objectives; Sharm el-Sheikh, Arish, Abu Uwayulah (Abu Ageila), and the Gaza Strip. The Egyptian blockade of the Tiran Straits was based at Sharm el-Sheikh and, by capturing the town, Israel would have access to the Red Sea for the first time since 1953, which would allow it to restore the trade benefits of secure passage to the Indian Ocean.[25]

The Gaza Strip was chosen as another military objective because Israel wished to remove the training grounds for fedayeen groups, and because Israel recognized that Egypt could use the territory as a staging ground for attacks against the advancing Israeli troops. Israel advocated rapid advances, for which a potential Egyptian flanking attack would present even more of a risk. Arish and Abu Uwayulah were important hubs for soldiers, equipment, and centers of command and control of the Egyptian Army in the Sinai.

Capturing them would deal a deathblow to the Egyptian's strategic operation in the entire Peninsula. The capture of these four objectives were hoped to be the means by which the entire Egyptian Army would rout and fall back into Egypt proper, which British and French forces would then be able to push up against an Israeli advance, and crush in a decisive encounter. On 24 October, Dayan ordered a partial mobilization. When this led to a state of confusion, Dayan ordered full mobilization, and chose to take the risk that he might alert the Egyptians. As part of an effort to maintain surprise, Dayan ordered Israeli troops that were to go to the Sinai to be ostentatiously concentrated near the border with Jordan first, which was intended to fool the Egyptians into thinking that it was Jordan that the main Israeli blow was to fall on.

On 28 October, Operation Tarnegol was effected, during which an Israeli Gloster Meteor NF.13 intercepted and destroyed an Egyptian Ilyushin Il-14 carrying Egyptian officers en route from Syria to Egypt, killing 16 Egyptian officers and journalists and two crewmen. The Ilyushin was believed to be carrying Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer and the Egyptian General Staff; however this was not the case.

The conflict began on 29 October 1956. At about 3:00 pm, Israeli Air Force Mustangs launched a series of attacks on Egyptian positions all over the Sinai. Because Israeli intelligence expected Jordan to enter the war on Egypt's side, Israeli soldiers were stationed along the Israeli-Jordanian frontier. The Israel Border Police militarized the Israel-Jordan border, including the Green Line with the West Bank, during the first few hours of the war. Israeli-Arab villages along the Jordanian border were placed under curfew. This resulted in the killings of 48 civilians in the Arab village of Kafr Qasim in an event known as the Kafr Qasim massacre. The border policemen involved in the killings were later tried and imprisoned, with an Israeli court finding that the order to shoot civilians was "blatantly illegal". This event had major effects on Israeli law relating to the ethics in war and more subtle effects on the legal status of Arab citizens of Israel, who at the time were regarded as a fifth column.[26]

It later became clear that Israel, France, and Britain had conspired to plan out the invasion. The three allies had attained a number of their military objectives, but the Suez Canal was useless. Heavy political pressure from the United States and the USSR led to a withdrawal. US President Eisenhower had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the US government's pound sterling bonds. Historians conclude the Suez Crisis "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers".[14][27]

The formation of the United Arab Republic (1958)

editAs political instability grew in Syria]], delegations from the country were sent to Nasser demanding immediate unification with Egypt.[28] Nasser initially turned down the request, citing the two countries' incompatible political and economic systems, lack of contiguity, the Syrian military's record of intervention in politics, and the deep factionalism among Syria's political forces.[28] However, in January 1958, a second Syrian delegation managed to convince Nasser of an impending communist takeover and a consequent slide to civil strife.[29] Nasser subsequently opted for union, albeit on the condition that it would be a total political merger with him as its president, to which the delegates and Syrian president Shukri al-Quwatli agreed.[30] On 1 February, the United Arab Republic (UAR) was proclaimed and, according to Dawisha, the Arab world reacted in "stunned amazement, which quickly turned into uncontrolled euphoria."[31] Nasser ordered a crackdown against Syrian communists, dismissing many of them from their governmental posts.[32][33]

On a surprise visit to Damascus to celebrate the union on 24 February, Nasser was welcomed by crowds in the hundreds of thousands.[34] Crown Prince Imam Badr of North Yemen was dispatched to Damascus with proposals to include his country in the new republic. Nasser agreed to establish a loose federal union with Yemen—the United Arab States—in place of total integration.[35] While Nasser was in Syria, King Saud planned to have him assassinated on his return flight to Cairo.[36] On 4 March, Nasser addressed the masses in Damascus and waved before them the Saudi check given to Syrian security chief and, unbeknownst to the Saudis, ardent Nasser supporter Abdel Hamid Sarraj to shoot down Nasser's plane.[37] As a consequence of Saud's plot, he was forced by senior members of the Saudi royal family to informally cede most of his powers to his brother, King Faisal, a major Nasser opponent who advocated pan-Islamic unity over pan-Arabism.[38]

A day after announcing the attempt on his life, Nasser established a new provisional constitution proclaiming a 600-member National Assembly (400 from Egypt and 200 from Syria) and the dissolution of all political parties.[38] Nasser gave each of the provinces two vice-presidents: Boghdadi and Amer in Egypt, and Sabri al-Asali and Akram al-Hawrani in Syria.[38] Nasser then left for Moscow to meet with Nikita Khrushchev. At the meeting, Khrushchev pressed Nasser to lift the ban on the Communist Party, but Nasser refused, stating it was an internal matter which was not a subject of discussion with outside powers. Khrushchev was reportedly taken aback and denied he had meant to interfere in the UAR's affairs. The matter was settled as both leaders sought to prevent a rift between their two countries.[39]

In 1958, Egypt and Syria formed a sovereign union known as the United Arab Republic, ending the Republic of Egypt.[40]

References

edit- ^ Abdel-Malek, A. (1964-03-19). "Nasserism And Socialism". Socialist Register. 1. ISSN 0081-0606.

- ^ Mansour, Thaer (2022-07-22). "Egypt's 1952 revolution: Seven decades of military rule". newarab. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ Lahav, Pnina. "The Suez Crisis of 1956 and its Aftermath: A Comparative Study of Constitutions, Use of Force, Diplomacy and International Relations". Boston University Law Review.

- ^ Mart, Michelle (2006-02-09). Eye on Israel: How America Came to View the Jewish State as an Ally. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6687-2.

- ^ "Egypt - Revolution, Republic, Nile | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ Alexander, 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Alexander, p. 42.

- ^ Hilton Proctor Goss and Charles Marion Thomas. American Foreign Policy in Growth and Action, 3rd ed. Documentary Research Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University, 1959. p. 273.

- ^ theguardian, The Egyptian Republic (20 June 1953). "The Egyptian Republic". The Guardian.

- ^ Britannica. "The revolution and the Republic".

- ^ a b Dekmejian 1971, p. 45

- ^ James 2008, p. 149

- ^ a b Goldschmidt 2008, p. 162

- ^ a b c d Ellis, Sylvia (2009-04-13). Historical Dictionary of Anglo-American Relations. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6297-5.

- ^ a b c Jankowski 2001, p. 68

- ^ a b "1956: Egypt Seizes Suez Canal". BBC News. 26 July 1956. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- ^ a b Aburish 2004, p. 108

- ^ Hamad 2008, p. 96

- ^ majalla, This day in history: The birth of the Egyptian Republic. "This day in history: The birth of the Egyptian Republic".

- ^ موقع الجمهورية المصرية, عام. "Gamal Abdel Nasser".

- ^ Peden, G. C. (December 2012). "SUEZ AND BRITAIN'S DECLINE AS A WORLD POWER*". The Historical Journal. 55 (4): 1073–1096. doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000246. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 162845802.

- ^ Mayer, Michael S. (2009). The Eisenhower Years. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1908-3.

- ^ "Suez Crisis | National Army Museum". www.nam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "What Was The Suez Crisis?". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "Suez Crisis | Definition, Summary, Location, History, Dates, Significance, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2023-11-14. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "What Was The Suez Crisis?". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ Peden, G. C. (December 2012). "SUEZ AND BRITAIN'S DECLINE AS A WORLD POWER*". The Historical Journal. 55 (4): 1073–1096. doi:10.1017/S0018246X12000246. ISSN 0018-246X. S2CID 162845802.

- ^ a b Dawisha 2009, pp. 193

- ^ Dawisha 2009, p. 198

- ^ Dawisha 2009, pp. 199–200

- ^ Dawisha 2009, p. 200

- ^ Aburish 2004, pp. 150–151

- ^ Podeh 1999, pp. 44–45

- ^ Dawisha 2009, pp. 202–203

- ^ Aburish 2004, p. 158

- ^ Dawisha 2009, p. 190

- ^ Aburish 2004, pp. 160–161

- ^ a b c Aburish 2004, pp. 161–162

- ^ Aburish 2004, p. 163

- ^ "Egypt, Syria Union Aim at Arab Unity". The San Francisco Examiner. Associated Press. February 2, 1958. Archived from the original on January 4, 2023. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

Sources

edit- Aburish, Said K. (2004), Nasser, the Last Arab, New York City: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-28683-5

- Dawisha, Adeed (2009), Arab Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: From Triumph to Despair, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-10273-3

- Dekmejian, Richard Hrair (1971), Egypt Under Nasir: A Study in Political Dynamics, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-87395-080-0

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2008), A Brief History of Egypt, New York: Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-6672-8

- Hamad, Mahmoud (2008), When the Gavel Speaks: Judicial Politics in Modern Egypt, ISBN 978-1-243-97653-6

- James, Laura M. (2008), "When Did Nasser Expect War? The Suez Nationalization and its Aftermath in Egypt", in Simon C. Smith (ed.), Reassessing Suez 1956: New Perspectives on the Crisis and Its Aftermath, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-6170-2

- Jankowski, James P. (2001), Nasser's Egypt, Arab Nationalism, and the United Arab Republic, Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, ISBN 1-58826-034-8

- Podeh, Elie (1999), The Decline of Arab Unity: The Rise and Fall of the United Arabic Republic, Portland: Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1-902210-20-4