Augustin Prosper Hacquard (18 September 1860 – 4 April 1901) was a French missionary who became Apostolic Vicar of Sahara and Sudan in 1898. After several years in Algeria, including a short period as head of the Armed Brothers of the Sahara, he was appointed to the French Sudan, the newly acquired territories along the Niger River to the east of Senegal, where he established several mission stations. The missionaries founded several villages, where they settled former slaves.

Augustin Prosper Hacquard | |

|---|---|

| Apostolic Vicar of Sahara and Sudan | |

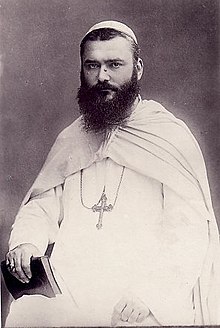

Augustin Hacquard in 1898 | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 8 September 1884 |

| Consecration | 28 August 1898 by François-Marie-Benjamin Richard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 September 1860 Albestroff, Moselle, France |

| Died | 4 April 1901 (aged 40) Niger River near Ségou, Mali |

| Nationality | French |

| Denomination | White Fathers |

| Occupation | Missionary |

Early years (1860–84)

editAugustin Prosper Hacquard was born on 18 September 1860 in Albestroff, Moselle, France.[1] He attended primary school, then in 1873 entered the minor seminary of Pont-à-Mousson, and in 1877 went on to the major seminary of Nancy. On 27 June 1878 he decided to seek admission to the White Fathers novitiate at Maison-Carrée in Algiers. His parents would not give their permission, but he left anyway and embarked from Marseille for Algiers on 1 September 1878.[1] At the Maison-Carrée the program included prayer, spiritual formation and the Arabic language. In September 1881 Hacquard was appointed a teacher at the Collège de Carthage and taught there for two years before resuming his theological studies in 1883.[1]

Hacquard was strongly built, bearded, lively and very brave. He learned to speak Arabic fluently.[2]

Priest in Algiers (1884–91)

editHacquard was ordained a priest of the White Fathers on 8 September 1884.[1] He was appointed a teacher of humanities at the minor seminary of Saint Eugène in Algiers. In 1886 Cardinal Charles Lavigerie put him in charge of the baccalaureate class and told him to prepare himself for his university entrance exam, which he passed first of 47 candidates in September 1886. He wanted to go with the next caravan to the Great Lakes led by Bishop John Joseph Hirth, but was told by the Cardinal that it would be a good test for him to wait a few years.[1] He was appointed Prefect of Studies at the minor seminary of Saint Eugène, a demanding job. On 28 July 1887 he obtained his degree from the faculty of Aix-en-Provence and was told by the Cardinal to prepare his doctorate on the ancient Christian Africa.[1]

Armed brothers of the Sahara (1891–93)

editA group of missionaries who tried to cross the Sahara were massacred in 1877, and another group was massacred in 1881.[2] The official Flatters expedition was also destroyed in 1881.[3] After this the authorities prohibited the White Fathers from trying to enter the southern Sahara.[2] However, in 1891 the Cardinal appointed Hacquard to Biskra as first superior of a new religious and military institute, the Frères armés du Sahara (Armed Brothers of the Sahara). The main role of these volunteers would be to receive slaves escaped from the caravans.[1] The lay brothers would give the slaves refuges and promote agriculture.[4] A barrack was built in Biskra for the brotherhood, who wore a uniform with elements from the garb of the crusaders and the French North African cavalry. The volunteers were expected to provide examples to the "heathens" of ascetic, martial Christian virility.[5]

The work was hard and spartan, but there were many volunteers attracted by the romance of the desert. Hacquard was very selective and out of 1,700 applications chose only 30, a number that soon dropped to 22. In October he and six brothers were posted to Ouargla.[1] One of the 22 Armed Brothers, the layman Maurice Delafosse, was later a member of the Temporary Slavery Commission of the League of Nations.[4] The Armed Brothers of the Sahara were portrayed in the international press as the Cardinal's private army.[2] The governor general of Algeria asked Lavigerie to disband them.[4] He complied in October 1892. Hacquard remained in charge of the mission in Ouargla until 21 July 1893, when he was sent to Maison Carrée.[1]

Tuareg exploration (1893–94)

editOn 10 September 1893 Hacquard and François Ménoret of the White Fathers were appointed to serve on a mission of exploration to Tuareg country led by Gaston Méry.[1] The other European members were Albert Bonnel de Mézières(fr) and Antoine Bernard d'Attanoux, a former officer who had become editor of Le Temps.[6] The mission set out in October 1893.[7] The leadership of the mission had not been well defined, and the members quarrelled.[8] Méry did not want to carry books or the geologist's equipment and would not listen to the advice of more experienced travellers.[1] He was emotionally unstable and had a violent temper. He shot a guide in the arm during an argument, and killed his interpreter's dog after it refused a command to attack a gazelle. At one point he threatened to blow everyone up with boxes of blasting powder.[9]

At Touggourt Méry announced that he would dispense with guides. The other members of the mission decided that they could not continue in these circumstances.[1] Méry left the expedition and returned to France.[10] On his return to Biskra Hacquard was offered command of the mission, but refused, and Antoine Bernard d'Attanoux took the position.[1] The mission left again on 12 January 1894.[1] It went south from Biskra past Touggourt and Ouargla, past Aïn Taïba, El Biodh and Temassinin, and along the Ighargharen valley to Lake Menghough.[7] Méry decided to return to the desert once more, at his own expense.[8] He left Toulouse in January 1894 with a companion named Moulai and followed the trail of the Attanoux mission which he rejoined at Ain-Taieba.[10] The two explorers fell out again, and Méry was repatriated a second time.[11] The mission returned to Algiers on 17 April 1894, and later that month Hacquard participated in a General Chapter of the White Fathers at Maison-Carrée. After returning to France Hacquard lectured about the Tuareg's in Lille and Paris.[1]

Ségou and Timbuktu (1894–95)

editAround this time the French moved inland from the coast of Senegal into what is now Mali and Burkino Faso, reached Timbuktu in 1894 and declared a protectorate over the French Sudan in 1895. Lavigerie's successor as Apostolic Vicar of the Sahara and Sudan, Bishop Anatole-Joseph Toulotte, decided to organize a mission in the Sudan, and in 1894 was given permission to enter the Sudan from Senegal with a mission headed by a Frenchman.[2] The Ministry of the Colonies issued the authorization on 9 November 1894 and on 25 December 1894 the first caravan, four White Fathers, left from Marseille. Hacquard was the leader of the group. They arrived in Dakar and went by train to Saint-Louis, where they stayed until 16 January 1895. The missionaries than travelled by boat up the Senegal River and reached Kayes on 12 February 1895. They continued by land to Ségou on the Niger River, which they reached on 1 April 1895.[1]

The White Father were committed to eliminating slavery. The Congregation of the Holy Spirit mission at Kita gave the first group of White Fathers two orphans. They often bought slaves, and also received refugees. A large caravan was stopped at Ségou just after the White Fathers arrived. Hacquard offered to look after the freed slaves and to give them huts, clothes, tools, seed and grain until the next harvest. For several years the mission operated a liberty village near Ségou.[12] On 30 April 1895 Hacquard and Father Dupuis took a boat down the Niger to Kabara, the port of Timbuktu, which they reached on 21 May 1895. They quickly established a mission where Hacquard ran the pharmacy and Dupuis taught about 15 children.[1] The mission in Timbuktu did not last long.[13]

Niger navigation and France (1896–97)

editHacquard was invited by Émile Auguste Léon Hourst(fr), commander of the French flotilla of the Niger, on a mission to investigate the hydrology of the river. The mission left Kabara on 22 January 1896. At Gao a large payment to the local ruler, Madidou, was needed to gain permission to continue. The mission reached Say on 7 April 1896, and established a fortified base on a wooded island while waiting for the water levels to rise enough for them to proceed. They started again on 15 September 1896, reached the Atlantic Ocean, and returned via Dahomey and Dakar to report to the Governor General. Hacquard went on from Dakar to France.[1]

The Niger voyage let Hacquard see for himself the conditions and the prospects for mission activity in the lands beside the Niger.[13] His account of the journey appeared in Les Missions catholiques in 1897.[1] Hacquard denied accusations that he was an explorer working for the government, saying, "I am more ambitious than that, I am a missionary."[13] Hacquard described the effect of famine years in the region,

Masters turn loose their slaves so they will not have to feed them (reserving the right to resume possession at the end of the crisis); many families pawn their children—this consists of delivering children capable of work in exchange for a sum between 15 and 50 francs; the parent can withdraw them by paying back the sum. The interest of the lender is to advance enough money that the family will never be able to return it. The growing children will always bring a profit. They are essentially slaves purchased at a relatively low price.[14]

On 31 March 1897 Hacquard told the Anti-Slavery Society in Paris, "... we have sought to follow the footsteps of our predecessors the Fathers of the Holy Spirit. ...We have adopted these poor victims, the slaves, and we now have Christian villages with several hundred inhabitants." In 1897 Hacquard persuaded the French Anti-Slavery Society to make liberty villages a priority. Ten of these villages were eventually founded by the missions in the Sudan.[12] The government also ran liberty villages for ex-slaves, and used the villagers as laborers. The White Fathers criticized these villages, and Hacquard suggested that the women in them often simply became concubines. The villages founded by the White Fathers were distant from government posts where possible.[15]

Hacquard stayed in France and Algeria for almost 11 months writing, lecturing, and preparing a double caravan of White Fathers and White Sisters for departure to the Sudan. In France he was chaplain to a community of about 100 nuns of the Congregation of Our Lady of Sion. He left Marseille on 25 October 1897 with eight nuns, two priests and two monks, and reached Ségou on 1 January 1898.[1]

Last years (1898–1901)

editOn 19 January 1898 Hacquard was appointed Titular Bishop of Rusicade and Apostolic Vicar of Sahara and Sudan.[16] He succeeded Toulotte in the latter role.[2] He was in Ségou when he was informed of the appointment. In a letter he wrote on 11 April 1898 he downplayed the significance of the promotion, noting that there was no use for ceremony at the mission and everyone shared the same food. He returned to France, arrived in Marseille on 17 July 1898 and received his episcopal consecration on 28 August 1898 in the chapel of the Dames de Sion, in Paris. He visited Rome to meet the Pope and the Cardinal Prefect of the Propaganda Fide.[1]

Hacquard left Marseille for the last time on 25 October 1898 with three new priests, two brothers and three sisters, and reached Ségou on 10 January 1899. After a month he set out to visit part of his huge vicariate. Between 24 February 1899 and 12 April 1899 he visited the Bobo, Samo and Mossi countries south of the river and spent a few days in Ouagadougou. He made another trip to the Mossi country from December 1899 to March 1900.[1] The missionaries had difficulty making converts in Bamako and Kayes, where most people were Muslim. In Ségou and Kita they did better, but Islam was growing fast there too. Their best prospects were in the south among the Mossi, Bobo and Minianka people, who had little contact with Islam. However, they were handicapped by lack of money and the insistence of the authorities that they keep their northern missions open.[12]

A mission had been founded at Bamako in 1897.[17] Hacquard founded mission stations among the Mossi and Gurma people of what is now Burkina Faso. He contacted the British authorities, and gained their permission to start a mission station in the north of the Gold Coast (now Ghana).[2] He noted that the Gold Coast could provide a refuge if the anti-clerical French administration made it impossible for missionaries to work in the French protectorate.[13] The missions took in many children, whether as pawns or purchases. There was a famine in 1899 when the price of grain rose tenfold. The missions at Segu and Banankuru purchased more than 100 people, all that they could afford.[14]

The missionaries were generally treated well by the soldiers, many of whom came from strictly religious families. The missions were useful to the authorities since they educated the local people to become clerks, minor officials and teachers, ran orphanages and supplied nurses and chaplains for the hospitals.[17] However, there were tensions. The missionaries maintained their independence from the state, often taught in local languages rather than French and could not accept the relaxed attitudes of the military to sex and slavery.[17]

Hacquard made another trip to Djenné, Bandiagara, Lake Débo and Dori in November–December 1900. He died in an accident on 4 April 1901 while bathing in the Niger at Ségou.[1]

Writings

editPublications by Hacquard include:[18][a]

- Augustin-Prosper Hacquard; Émile Hourst (1897), De Tombouctou aux bouches du Niger avec la mission Hourst

- Augustin-Prosper Hacquard; Dupuis (1897), Manuel de la langue soñgay, parlée de Tombouctou à Say dans la boucle du Niger, Paris: J. Maisonneuve, p. 253

- Augustin-Prosper Hacquard (1900), Monographie de Tombouctou, Paris: Société des études coloniales et maritimes, p. 119

Notes

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Vanrenterghem 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g Shorter 2003.

- ^ Brower 2011, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2011, p. 383.

- ^ White & Daughton 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Pottier 1947, p. 272.

- ^ a b Dubief 1999, p. 113.

- ^ a b Guénot 1896, p. 603.

- ^ Brower 2011, p. 207.

- ^ a b Marbeau & Demanche 1896, p. 234.

- ^ Guénot 1896, p. 605.

- ^ a b c Klein 1998, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d Shorter 2011, p. 67.

- ^ a b Klein 1998, p. 117.

- ^ Scully & Paton 2005, p. 168.

- ^ Cheney.

- ^ a b c Klein 1998, p. 115.

- ^ a b Augustin-Prosper Hacquard (1860–1901) – BnF.

- ^ Cheney (2).

Sources

edit- Augustin-Prosper Hacquard (1860–1901) (in French), BnF: Bibliotheque nationale de France, retrieved 2018-02-18

- Brower, Benjamin Claude (2011), A Desert Named Peace: The Violence of France's Empire in the Algerian Sahara, 1844–1902, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-15493-2, retrieved 2017-12-15

- Cheney, David M., "Bishop Augustin Prosper Hacquard, M. Afr.", Catholic Hierarchy, retrieved 2018-02-17

- Cheney (2), David M., "Bishop Augustin Hacquard", Catholic Hierarchy, retrieved 2018-02-18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Clarke, P. B. (1974), "The Methods and Ideology of the Holy Ghost Fathers in Eastern Nigeria 1885-1905", Journal of Religion in Africa, 6 (2), Brill: 81–108, doi:10.2307/1594882, JSTOR 1594882

- Dubief, Jean (1999-01-01), L'Ajjer, Sahara central (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-86537-896-8, retrieved 2017-12-15

- Guénot, S. (1896), "Mort de M. Gaston MÉRY", Revue (in French), Société de géographie de Toulouse, retrieved 2017-12-14

- Klein, Martin A. (1998-07-28), Slavery and Colonial Rule in French West Africa, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-59678-7, retrieved 2018-02-19

- Marbeau, Édouard; Demanche, Georges, eds. (1896), "L'Explorateur Gaston Mery (1844-1896)", Revue francaise de l'etranger et des colonies et Exploration, gazette (in French), Au Secrétariat général de l'Institut de Carthage, retrieved 2017-12-15

- Pottier, René (1947), Histoire du Sahara (in French), Nouvelles Editions Latines, ISBN 978-2-7233-0859-5, retrieved 2017-12-15

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2011-10-20), Slavery in the Modern World: A History of Political, Social, and Economic Oppression [2 volumes]: A History of Political, Social, and Economic Oppression, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-85109-788-3, retrieved 2018-02-19

- Scully, Pamela; Paton, Diana (2005-09-13), Gender and Slave Emancipation in the Atlantic World, Duke University Press, ISBN 0-8223-8746-8, retrieved 2018-02-19

- Shorter, Aylward (2003), "Hacquard, Prosper Augustin", Dictionary of African Christian Biography, retrieved 2018-02-18

- Shorter, Aylward (2011-12-05), Les Pères Blancs au temps de la conquête coloniale. Histoire des Missionnaires d'Afrique 1892-1914 (in French), KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 978-2-8111-5003-7, retrieved 2018-02-19

- Vanrenterghem, Joseph (February 2005), MONSEIGNEUR AUGUSTIN HACQUARD (in French), Bry-sur-Marne: Pères Blancs, retrieved 2018-02-17

- White, Owen; Daughton, J.P. (2012-09-27), In God's Empire: French Missionaries in the Modern World, OUP USA, ISBN 978-0-19-539644-7, retrieved 2018-02-19