2012 is a 2009 American epic science fiction disaster film directed by Roland Emmerich, written by Emmerich and Harald Kloser, and stars John Cusack, Amanda Peet, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Oliver Platt, Thandiwe Newton,[a] Danny Glover and Woody Harrelson. Based on the 2012 phenomenon, its plot follows geologist Adrian Helmsley (Ejiofor) and novelist Jackson Curtis (Cusack) as they struggle to survive an eschatological sequence of events including earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, megatsunamis, and a global flood.

| 2012 | |

|---|---|

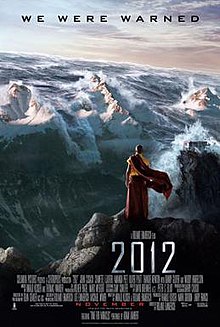

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roland Emmerich |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dean Semler |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Releasing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 158 minutes |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $200 million[2] |

| Box office | $791.2 million[3] |

Filming, planned for Los Angeles, began in Vancouver in early August 2008 and wrapped up in mid-October 2008.[4][5] The film ran a lengthy advertising campaign, which included the creation of a website from its main characters' point of view[6] and a viral marketing website on which filmgoers could register for a lottery number to save them from the ensuing disaster.[7]

2012 was released in the United States by Sony Pictures Releasing on November 13, 2009, to commercial success, grossing over $791 million worldwide against a production budget of $200 million, becoming the fifth highest-grossing film of 2009. The film received mixed reviews from critics. It was nominated for Best Action, Adventure, or Thriller Film and Best Special Effects at the 36th Saturn Awards, and for Best Visual Effects at the 15th Critics' Choice Awards.

Plot

editIn 2009, American geologist Adrian Helmsley visits astrophysicist Satnam Tsurutani in East India and learns that a new type of neutrino from a solar flare is heating the Earth's core. Returning to Washington, D.C., Adrian alerts White House Chief of Staff Carl Anheuser and President Thomas Wilson.

In 2010, over forty-six nations begin building nine arks in the Himalayas, in Tibet, and storing artifacts in secure locations. Nima, a Buddhist monk, is evacuated with his grandparents, and his brother Tenzin joins the ark project. Additional funding is secretly raised by selling tickets to the rich for €1 billion per person.

In 2012, struggling science-fiction writer Jackson Curtis is a chauffeur in Los Angeles for Russian billionaire Yuri Karpov. Jackson's former wife Kate and their children, Noah and Lilly, live with Kate's boyfriend, plastic surgeon and amateur pilot Gordon Silberman. Jackson takes Noah and Lilly camping in Yellowstone National Park. When they find Yellowstone Lake dried up and fenced off by the United States Army, they are caught and brought to Adrian. They later meet conspiracy theorist and radio personality Charlie Frost, who tells Jackson of Charles Hapgood's earth crust displacement theory and the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar predict the end of world in 2012 and worldwide catastrophe, and that the world's governments silence anyone attempting to warn the public.

Despite his initial skepticism, Jackson heeds Charlie's warning after seeing indications that validate it. At the Santa Monica Airport, after dropping off Yuri's sons Alec and Oleg, who also warn of impending doom as they board a plane, he rents a Cessna 340A and sets out to rescue his family. As the Pacific Coast suffers a horrific 10.9 earthquake along the San Andreas Fault, Jackson and his family reach the airport and get the Cessna airborne. The group flies to Yellowstone and Jackson retrieves Charlie's map of the arks' location. The Yellowstone Caldera erupts, with Charlie staying behind to finish his broadcast; he is killed by debris. Realizing they need a larger plane to fly to Asia, the group lands at McCarran International Airport south of Downtown Las Vegas to search for one.

Adrian, Carl, and First Daughter Laura fly to the arks, while President Wilson remains in the White House to address the nation. Jackson finds the Karpovs, Yuri's girlfriend Tamara, and their pilot Sasha. Sasha and Gordon fly the families out in an Antonov An-500, as the volcanic ashes from the Caldera envelop the Las Vegas Valley. The planet's crust shifts resulting in billions dead in disasters worldwide, including President Wilson. With the presidential line of succession gone, following the death of the Vice President and the disappearance of the Speaker of the House, Carl appoints himself acting commander-in-chief.

Upon reaching the Himalayas, the Antonov's engines malfunction. As the plane touches down on a glacier, the party uses a Bentley Flying Spur stored in the hold to escape, except Sasha, who stays in the cockpit and is killed when the jet goes over a cliff. The survivors are spotted by Chinese Air Force helicopters, which take only the three ticket-bearing Karpovs, leaving Tamara and Jackson's family behind. The abandoned group later encounters Nima, who, with his own family, takes them to the arks, where they stow away on Ark 4 with Tenzin's help.

With a megatsunami approaching, Carl orders the loading gates closed, though most people have not boarded. Adrian persuades the captain and the other surviving world leaders to allow passengers aboard the arks, but Yuri falls to his death as he pushes his sons onto Ark 4. The gate closes after survivors are on board, injuring Tenzin and fatally crushing Gordon. Tenzin's impact driver used to access the ship gets lodged in the gate mechanism, preventing it from closing completely and disabling the ship's engines. As the tsunami strikes, the ark starts flooding as it is set adrift, heading for Mount Everest. Adrian rushes to clear the gears, but watertight doors close, trapping the stowaways and drowning Tamara. Noah and Jackson dislodge the tool. The crew regains control of the ark, while Jackson and Noah make it back safely.

Twenty-seven days later, the waters are receding. The arks approach the Cape of Good Hope, where the Drakensberg Mountains are the highest mountain range on Earth. Adrian and Laura begin a relationship, while Jackson and Kate reconcile.

Alternate ending

editAn alternate ending appears in the film's DVD release. After Ark 4's Captain Michaels announces that they are heading for the Cape of Good Hope, Adrian learns by phone that his father, Harry, and Harry's friend Tony Delgatto, survived a megatsunami that capsized their cruise ship Genesis. Adrian and Laura strike up a friendship with the Curtis family, Kate thanks Laura for taking care of Lilly, Laura tells Jackson that she enjoyed his book Farewell Atlantis, and Jackson and Adrian have a conversation reflecting on the events of the worldwide crisis. Carl apologizes to Adrian and Laura for his negligent actions. Jackson returns Noah's cell phone, which he recovered during the Ark 4 flood. Finally, the ark finds the shipwrecked Genesis and its survivors on a beach.[8]

Cast

edit- John Cusack as Jackson Curtis, a struggling writer and a father of two children.[9]

- Chiwetel Ejiofor as geologist Adrian Helmsley, chief science advisor to the U.S. President.[10]

- Amanda Peet as Kate Curtis, a medical student and Jackson's former wife.[11]

- Oliver Platt as Carl Anheuser, the White House Chief of Staff.

- Thandiwe Newton (credited as Thandie Newton) as Laura Wilson, an art expert and First Daughter and Adrian's love interest.

- Tom McCarthy as Gordon Silberman, a plastic surgeon/pilot and Kate's boyfriend.[12]

- George Segal as Tony Delgatto, a jazz singer.

- Danny Glover as Thomas Wilson, the President of the United States and Laura's father.

- Woody Harrelson as Charlie Frost, a fringe science conspiracy theorist and radio talk-show host.

- Liam James as Noah Curtis, Jackson and Kate's son.

- Morgan Lily as Lilly Curtis, Jackson and Kate's daughter.

- Blu Mankuma as Harry Helmsley, Adrian's father and Tony Delgatto's vocal partner.

- Zlatko Burić as Yuri Karpov, a Russian billionaire and former boxer.

- Beatrice Rosen as Tamara Jikan, Yuri's girlfriend.

- John Billingsley as Frederick West, a colleague of Adrian.

- Chin Han as Tenzin, an ark worker who attempts to save his family.

- Osric Chau as Nima, a Buddhist monk and Tenzin's younger brother.

- Alexandre Haussmann and Philippe Haussmann as Alec and Oleg Karpov, Yuri's twin sons.

- Jimi Mistry as Satnam Tsurutani, an Indian astrophysicist who discovers the neutrinos which are warming Earth's crust.

- Johann Urb as Sasha, Yuri's pilot.

- Ryan McDonald as Scotty, Adrian and Frederick's assistant.

- Stephen McHattie as Captain Michaels, the captain of Ark 4.

- Lisa Lu as Grandmother Sonam, Tenzin & Nima's grandmother.

- Henry O as Lama Rinpoche, a Buddhist monk.

- Patrick Bauchau as Roland Picard, the director of the Louvre who is killed with a car bomb by the U.S. government.

- Chang Tseng as Grandfather Sonam, Tenzin & Nima's grandfather.

- Karin Konoval as Sally, President Wilson's secretary.

- Agam Darshi as Aparna Tsurutani, Satnam's wife.

- Michael Buffer as himself, announcing for a boxing match in Las Vegas.

- Dean Marshall as the Ark 4 communications officer.

- Zinaid Memišević as Sergey Makarenko, the President of Russia.

- Merrilyn Gann as the German Chancellor.

- Lyndall Grant as Arnold Schwarzenegger, the Governor of California.

- Vincent Cheng as a Chinese colonel.

- Leonard Tenisci as the Italian Prime Minister.

- Parm Soor as the Saudi Arabian Prince who helps to pay for the construction of the Arks.

- Elizabeth Richard as Queen Elizabeth II.

- Frank C. Turner as Preacher.

Production

editDevelopment

editGraham Hancock's Fingerprints of the Gods was listed in 2012's credits as the film's inspiration,[13] and Emmerich said in a Time Out interview: "I always wanted to do a biblical flood movie, but I never felt I had the hook. I first read about the Earth's crust displacement theory in Graham Hancock's Fingerprints of the Gods."[14] He and composer-producer Harald Kloser worked closely together, co-writing a spec script (also titled 2012) which was marketed to studios in February 2008. A number of studios heard budget projection and story plans from Emmerich and his representatives, a process the director had previously undertaken for Independence Day (1996) and The Day After Tomorrow (2004).[15]

Later that month, Sony Pictures Entertainment obtained the rights to the spec script. Planned for distribution by Columbia Pictures,[16] 2012 cost less than its budget; according to Emmerich, the film was produced for about $200 million.[2]

Filming

editFilming, originally scheduled to begin in Los Angeles in July 2008,[5] began in Kamloops, Savona, Cache Creek, and Ashcroft, British Columbia, in early August 2008 and wrapped up in mid-October 2008.[4][17] With a Screen Actors Guild strike looming, the film's producers had a contingency plan in case of a walkout by actors.[18] Uncharted Territory, Digital Domain, Double Negative, Scanline, and Sony Pictures Imageworks were hired to create the film's visual effects.

The film depicts the destruction of several cultural and historical landmarks around the world. Emmerich said that the Kaaba was considered for selection, but Kloser was concerned about a possible fatwa against him.[19]

Soundtrack

editThe film's score was composed by Harald Kloser and Thomas Wander. Adam Lambert contributed a song to the film, "Time for Miracles", which was originally written by Alain Johannes and Natasha Shneider.[20] The 24-song soundtrack includes "Fades Like a Photograph" by Filter and "It Ain't the End of the World" by George Segal and Blu Mankuma.[21] "Master of Shadows" by Two Steps from Hell was used for the film's trailers.

Release

editMarketing

edit2012 was marketed through the fictional Institute for Human Continuity, at a viral marketing website that was created by the movie studio. The website featured main-character Jackson Curtis' book Farewell Atlantis, streaming media, blog updates, and radio broadcasts from zealot Charlie Frost on his website, This Is the End.[6] On November 12, 2008, the studio released the first trailer for 2012, which ended with a suggestion to viewers to "find out the truth" by entering "2012" on a search engine. The Guardian called the film's marketing "deeply flawed", associating it with "websites that make even more spurious claims about 2012".[22]

At the website, filmgoers could register for a lottery number to be part of a small population that would be rescued from the global destruction.[7] David Morrison of NASA, who had received over 1,000 inquiries from people who thought the website was genuine, condemned it. "I've even had cases of teenagers writing to me saying they are contemplating suicide because they don't want to see the world end", Morrison said. "I think when you lie on the internet and scare children to make a buck, that is ethically wrong."[23] Another marketing website promoted Farewell Atlantis.[6]

Comcast organized a "roadblock campaign" to promote the film in which a two-minute scene was broadcast on 450 American commercial television networks, local English-language and Spanish-language stations, and 89 cable outlets during a ten-minute window between 10:50 and 11:00 pm Eastern and Pacific Time on October 1, 2009.[24] The scene featured the destruction of Los Angeles and ended with a cliffhanger, with the entire 5:38 clip available on Comcast's Fancast website. According to Variety, "The stunt will put the footage in front of 90% of all households watching ad-supported TV, or nearly 110 million viewers. When combined with online and mobile streams, that could increase to more than 140 million".[24]

Theatrical

edit2012 was released to cinemas on November 13, 2009, in Indonesia, Mexico, Sweden, Canada, Denmark, China, India, Italy, the Philippines, Turkey, the United States, and Japan.[25] According to Sony Pictures, the film could have been completed for a summer release, but a delay allowed more time for production.[citation needed]

Home media

editThe DVD and Blu-ray versions were released on March 2, 2010. The two-disc Blu-ray edition includes over 90 minutes of features, including Adam Lambert's music video for "Time for Miracles" and a digital copy for PSP, PC, Mac, and iPod.[26] A 3D version was released in Cinemex theaters in Mexico in February 2010.[27] It was later released on Ultra HD Blu-ray on January 19, 2021.[citation needed]

Reception

editBox office

edit2012 grossed $166.1 million in North America and $603.5 million in other territories for a worldwide total of $769.6 million against a production budget of $200 million,[3] making it the first film to gross over $700 million worldwide without making $200 million domestically.[28] Worldwide, it was the fifth-highest-grossing 2009 film[29] and the fifth-highest-grossing film distributed by Sony-Columbia, (behind Sam Raimi's Spider-Man trilogy and Skyfall).[30] 2012 is the second-highest-grossing film directed by Roland Emmerich, behind Independence Day (1996).[31] It earned $230.5 million on its worldwide opening weekend, the fourth-largest opening of 2009 and for Sony-Columbia.[32]

2012 ranked number one on its opening weekend, grossing $65,237,614 on its first weekend (the fourth-largest opening for a disaster film).[33] Outside North America it is the 28th-highest-grossing film, the fourth-highest-grossing 2009 film,[34] and the second-highest-grossing film distributed by Sony-Columbia, after Skyfall. 2012 earned $165.2 million on its opening weekend, the 20th-largest overseas opening.[35] In total earnings, the film's three highest-grossing territories after North America were China ($68.7 million), France and the Maghreb ($44.0 million), and Japan ($42.6 million).[36]

In 2020, the film received renewed interest during the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming the second-most popular film and seventh-most popular overall title on Netflix in March 2020.[37]

Critical response

editOn Rotten Tomatoes, 2012 has an approval rating of 39% based on 247 reviews and an average rating of 5.20/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Roland Emmerich's 2012 provides plenty of visual thrills, but lacks a strong enough script to support its massive scope and inflated length."[38] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 49 out of 100 based on 34 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[39] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[40]

Roger Ebert praised 2012, giving it 3+1⁄2 stars out of 4 and saying that it "delivers what it promises and since no sentient being will buy a ticket expecting anything else, it will be, for its audiences, one of the most satisfactory films of the year".[41] Ebert and Claudia Puig of USA Today called the film the "mother of all disaster movies".[41][42] Dan Kois of The Washington Post gave the film 4 out of 4 stars, deeming it "the crowning achievement in Emmerich's long, profitable career as a destroyer of worlds."[43] Jim Schembri of The Age gave the film 4 out of 5 stars, describing it as "a great, big, fat, stupid, greasy cheeseburger of a movie designed to show, in vivid detail, what the end of human civilisation will look like according to his vast army of brilliant visual effects artists."[44]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone compared the film to Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, writing: "Beware 2012, which works the dubious miracle of almost matching Transformers 2 for sheer, cynical, mind-numbing, time-wasting, money-draining, soul-sucking stupidity."[45] Rick Groen of The Globe and Mail gave the film 1 out of 4 stars, writing: "As always in Emmerich's rollicking Armageddons, the cannon speaks with an expensive bang, while the fodder gets afforded nary a whimper."[46] Christopher Orr of The New Republic wrote that the film's "ludicrous thrills begin burning themselves out by the movie's midpoint", and added: "As the movie approaches its two-and-a-half hour mark, you, too, may feel that The End can't come soon enough."[47] Tim Robey of The Daily Telegraph gave the film 2 out of 5 stars, saying that it was "dim, dim, dim, and so absurdly overscaled that we're not supposed to mind."[48] Linda Barnard of the Toronto Star gave the film 1 out of 4 stars, writing: "the clunky script and kitchen-sink approach to Emmerich's global apocalypse tale... makes the movie fail on a bunch of fronts."[49]

Accolades

edit

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards[51] | Best Visual Effects | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Mike Vézina | Nominated |

| NAACP Image Award[50] | Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture | Chiwetel Ejiofor | Nominated |

| Danny Glover | Nominated | ||

| Motion Picture Sound Editors[52] | Best Sound Editing – Music in a Feature Film | Fernand Bos, Ronald J. Webb | Nominated |

| Best Sound Editing – Sound Effects and Foley in a Feature Film | Fernand Bos, Ronald J. Webb | Nominated | |

| Satellite Awards[53] | Best Sound (Editing and Mixing) | Paul N.J. Ottosson, Michael McGee, Rick Kline, Jeffrey J. Haboush, Michael Keller | Won |

| Best Visual Effects | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Mike Vézina | Won | |

| Best Art Direction and Production Design | Barry Chusid, Elizabeth Wilcox | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | David Brenner, Peter S. Elliot | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards[54] | Best Action, Adventure, or Thriller Film | 2012 | Nominated |

| Best Special Effects | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Mike Vézina | Nominated | |

| Visual Effects Society Awards[55] | Outstanding Visual Effects in a Visual Effects-Driven Feature Motion Picture | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Josh Jaggars | Nominated |

| Best Single Visual Effect of the Year | Volker Engel, Marc Weigert, Josh R. Jaggars, Mohen Leo for "Escape from L.A." | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Created Environment in a Feature Motion Picture | Haarm-Pieter Duiker, Marten Larsson, Ryo Sakaguchi, Hanzhi Tang for "Los Angeles Destruction" | Nominated |

Canceled television spin-off

editIn 2010 Entertainment Weekly reported a planned spin-off television series, 2013, which would have been a sequel to the film.[56] 2012 executive producer Mark Gordon told the magazine, "ABC will have an opening in their disaster-related programming after Lost ends, so people would be interested in this topic on a weekly basis. There's hope for the world despite the magnitude of the 2012 disaster as seen in the film. After the movie, there are some people who survive, and the question is how will these survivors build a new world and what will it look like. That might make an interesting TV series."[56] However, plans were canceled for budget reasons.[56] It would have been Emmerich's third film to spawn a spin-off; the first was Stargate (followed by Stargate SG-1, Stargate Infinity, Stargate Atlantis, Stargate Universe), and the second was Godzilla (followed by the animated Godzilla: The Series).

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "2012". American Film Institute. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Blair, Ian (November 6, 2013). "'2012's Roland Emmerich: Grilled". The Wrap. Archived from the original on November 14, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ a b "2012". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on February 18, 2021. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Where Was 2012 Filmed?". March 27, 2021.

- ^ a b Siegel, Tatiana (May 19, 2014). "John Cusack set for 2012". Variety. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Farewell Atlantis by Jackson Curtis – Fake website". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Billington, Alex (November 15, 2012). "Roland Emmerich's 2012 Viral — Institute for Human Continuity". FirstShowing.net. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Orange, B. Alan. "EXCLUSIVE VIDEO: Watch the Alternate Ending for '2012'!". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on December 18, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ Foy, Scott (October 2, 2009). "Five Hilariously Disaster-ffic Minutes of 2012". Dread Central. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Simmons, Leslie (May 19, 2008). "John Cusack ponders disaster flick". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Simmons, Leslie; Kit, Borys (June 13, 2008). "Amanda Peet is 2012 lead". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Kit, Borys (July 1, 2008). "Thomas McCarthy joins 2012". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ "2012 (2015) – Credit List" (PDF). chicagoscifi.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ^ Emmerich, Roland (November 16, 2009). "Roland Emmerich's guide to disaster movies". Time Out (Interview). Interviewed by David Jenkins. Archived from the original on November 16, 2009. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (February 19, 2014). "Studios vie for Emmerich's 2012". Variety. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (February 21, 2014). "Sony buys Emmerich's 2012". Variety. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ "2012 Filmed in Thompson Region!". Tourismkamloops.com. December 14, 2012. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ "Big Hollywood films shooting despite strike threat". Reuters. August 1, 2008. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ Child, Ben (October 3, 2015). "Emmerich reveals fear of fatwa axed 2012 scene". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Vena, Jocelyn (November 4, 2009). "Adam Lambert Feels 'Honored' To Be On '2012' Soundtrack". MTV Movie News. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ^ "2012: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Amazon.com. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ^ Pickard, Anna (November 25, 2014). "2012: a cautionary tale about marketing". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ^ Connor, Steve (October 17, 2009). "Relax, the end isn't nigh". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Graser, Mark (September 23, 2009). "Sony readies 'roadblock' for 2012". Variety. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ "2012 Worldwide Release Dates". sonypictures.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Early Art and Specs: 2012 Rocking on to DVD and Blu-ray". DreadCentral. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ^ "Cinemex". cinemex.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2013.

- ^ Mendelson, Scott (June 12, 2017). "Box Office: Johnny Depp's 'Pirates 5' Breaks Walt Disney's Memorial Day Curse". Forbes. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "2009 Worldwide Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 21, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ "Roland Emmerich". boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ "All Time Worldwide Opening Records at the Box Office". boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ "Disaster Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- ^ "Overseas Total Yearly Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ "Overseas Total All Time Openings". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "2012 (2009) – International Box Office Results – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Clark, Travis (March 20, 2020). "Movies and TV shows about pandemics and disasters are surging in popularity on Netflix". Business Insider. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ "2012". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "2012". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (November 15, 2009). "'2012' Dominates For $225M 5-Day Launch Worldwide; 'Xmas Carol' Holds Well; 'Precious' & 'Fantastic Mr. Fox' Play To Packed Theaters; 'Pirate Radio' Sinks". Deadline.

Despite dismal reviews, the film received an "A" Cinemascore for moviegoers under 18 and a "B+" overall.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (November 12, 2009). "The late, great planet Earth: A thoroughly destroyable show". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (November 13, 2009). "'2012': Now that's Armageddon!". USA Today. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ^ Kois, Dan (November 13, 2009). "Movie review: '2012' is a perfect disaster". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Schembri, Jim (November 12, 2009). "2012". The Age. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Travers, Peter (November 12, 2009). "2012: Review". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 15, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Groen, Rick (November 12, 2009). "Apocalypse by the numbers". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Orr, Christopher (November 13, 2009). "The Mini-Review: '2012'". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Robey, Tim (November 4, 2013). "2012, review". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Barnard, Linda (November 12, 2009). "2012: No end in sight". The Toronto Star. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "The 41st NAACP Image Awards". NAACP Image Award. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "The 15th Annual Critics Choice Movie Awards". Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "2010 Golden Reel Award Nominees: Feature Films". Motion Picture Sound Editors. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "Satellite Awards Announce 2009 Nominations". Filmmisery.com. November 29, 2009. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ Miller, Ross (February 19, 2010). "Avatar Leads 2010 Saturn Awards Nominations". Screenrant.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ^ "8th Annual VES Awards". visual effects society. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ a b c Rice, Lynette (March 2, 2010). "ABC passes on '2012' TV show". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 17, 2010. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

External links

edit- Official website

- 2012 at IMDb

- 2012 at AllMovie

- 2012 at the TCM Movie Database

- 2012 at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- 2012 at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2012 at Metacritic

- 2012 at Box Office Mojo