Union County is a county located in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,244.[2] Its county seat is Union.[3] The county was created in 1785.[4]

Union County | |

|---|---|

Union County Carnegie Library | |

| Motto(s): "Gear Up" "A Great Place To Do Business - And Live Life!" | |

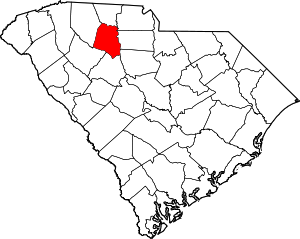

Location within the U.S. state of South Carolina | |

South Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 34°41′N 81°37′W / 34.69°N 81.62°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1785 |

| Named for | The old Union Church[1] |

| Seat | Union |

| Largest community | Union |

| Area | |

| • Total | 515.44 sq mi (1,335.0 km2) |

| • Land | 513.59 sq mi (1,330.2 km2) |

| • Water | 1.85 sq mi (4.8 km2) 0.36% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 27,244 |

| • Estimate (2023) | 26,629 |

| • Density | 53.04/sq mi (20.48/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 5th |

| Website | gearupunionsc |

Union County is included in the Spartanburg, SC Metropolitan Statistical Area,[5] which is also part of the Greenville-Spartanburg-Anderson, SC Combined Statistical Area.

History

editEarly settlement

editThe area that includes Union County was once controlled by the Cherokee Indians and they used it as a hunting ground. Up until recent years, one could find numerous arrowheads with little effort throughout the county.[6]

The first European settlers in Union County came from the backcountry of Virginia and Pennsylvania; more than three-fourths were Scots-Irish Presbyterians. It has been suggested that the first group of pioneers arrived as early as 1751. They settled in the northwestern section of the county near a small river that would later be named Fairforest Creek. According to tradition, Mr. McElwaine, a member of the party looked out at the thick woodlands and exclaimed, "What a fair forest!" At the time of their arrival, wild buffalo and horses abounded as well as panthers and cougars, which were called "tigers" or "tygers" by the settlers. This may be where the Tyger River got its name.[6] Another group of Scots-Irish settlers arrived in the late 1750s, all of whom were Presbyterians of Scottish descent, they consisted of five married couples and their children from the village of Ballinamallard, four married couples and their children from the village of Kesh and two married couples with their eight parents and their total of eleven children from the village of Caledon in County Tyrone, Ireland in what has since become Northern Ireland.[7]

The early settlers established Fairforest Presbyterian Church, the first house of worship in Union County. Around 1754, the Brown's Creek area was first settled, about four miles northeast of the present city of Union. A log church or meetinghouse was built and shared among several denominations that could not yet afford their own separate structures. The county and county seat were named for this "Union" church. Quakers arrived in the mid-1750s and settled the southern portion of the county, establishing Cane Creek Church in the Santuc community, and Padgett's Creek Church in the Cross Keys community. The Quakers left in the early 1800s because of their opposition to slavery. Baptists from North Carolina, under the leadership of Rev. Philip Mulkey, reached the Broad River in Fairfield County, SC in 1759. They relocated to Union County in 1762 and in 1771 formally organized into the first Baptist church in the South Carolina upcountry known as Fairforest Baptist Church. Many Baptist churches throughout the upcountry are descended from this original congregation. The congregation later moved to a site on present day SC Hwy 18 between Union and Jonesville where it remains to this day.[6]

Revolutionary period

editDuring the first part of the American Revolution, the South Carolina backcountry was fairly quiet. In 1776, Fairforest Church became the hub for Union County. Although divided, it was majority Loyalists.[8] The Fairforest Church became the headquarters for the Loyalists. Following the war the church became Padgetts Creek Baptist Church.[8] Following the fall of Charleston in 1780, the British began focusing their attention on the Carolinas. At least five battles were fought in or near Union County, including Musgrove Mill, Fishdam and Blackstock. The county also produced many notable heroes including Lt. Col. James Steen. The war divided the population between Loyalists and Patriots. This resulted in churches splitting up and settlers moving out of the area. Personal property was damaged by both sides.[6]

Following the war, the county seat was established at Unionville (now Union) and a courthouse was constructed. In 1791, the South Carolina Legislature established a district court that included Spartanburg, Union, Chester, and York counties. The area was called the Pinckney District and its headquarters was established at a central location in Union County. Land was cleared and streets were laid out for a new town that would be called Pinckneyville. A courthouse and jail were built for the new judicial district and a college was to be established in the town.[6]

Local tradition states that Pinckneyville was to be home to the United States Military Academy, but lost to West Point by one vote in Congress. Instead, local historians say that Pinckneyville was considered as the site for a federal arsenal. This was likely the source of the legend. In 1799, the General Assembly decided to restructure the state court system. Subsequently, the Pinckney District was abolished; with the loss of the court and associated businesses, Pinckneyville became a ghost town.[6]

Antebellum period

editDuring the early 1800s settlers developed large-scale cotton growing in the fertile soil of southern Union County, based on the use of enslaved labor. The demand for slaves in the Deep South drove the domestic market, and more than one million slaves were forcibly transported to the South in the antebellum years. There were numerous plantations in the county, several that are still standing, such as Rose Hill Plantation and the Cross Keys House. Rose Hill was the home of South Carolina's "Secession Governor," William Henry Gist. The northern section of the county was mostly home to yeoman farmers and small scale planters who owned fewer slaves.[6]

The county grew steadily during the antebellum period but remained almost fully agrarian. Stores and other businesses were established in the town of Union and a new courthouse and jail were designed for the town in 1823 by famed architect Robert Mills, designer of the Washington Monument. The courthouse was demolished in 1911, but the jail is still standing and in use by the City of Union. It is located beside the present courthouse, constructed in 1913.[6]

Civil War and aftermath

editThe Civil War brought a standstill to the county's growth and progress. Many local men rushed to enlist in the Confederate Army and numerous units of Union County soldiers served on battlefields across the South. On April 20, 1861, a strange object appeared in the sky above the Kelly-Kelton community of northeastern Union County. A large hot air balloon called the Enterprise descended to the ground, piloted by Professor T.S.C. Lowe, who had left Cincinnati, Ohio the day before. He had attempted to fly from Ohio to Washington, D.C. but instead was swept southward across Virginia into South Carolina. The locals crowded around this mysterious object, many insisting that Lowe be "shot on the spot," as they believed him to be a Northern spy. Local tradition states that Professor Lowe gave a Masonic distress sign and his life was saved by the Masons in the crowd. Eventually he would make it back to the North and work with the Union Army on aerial reconnaissance projects during the war. At the close of the war, Confederate President Jefferson Davis came through Union County following the fall of Richmond in 1865. He and his entourage crossed the ferry at Pinckneyville and made their way to the town of Union. They dined at the William Wallace house on Et Main Street in Union and the Cross Keys house in southwestern Union County before his eventual capture in Georgia.[6]

Following the war, a system of sharecropping and tenant farming was established to take the place of slavery and provide a consistent labor force. Union County's history parallels the history of much of the South during Reconstruction. The county was known for widespread Ku Klux Klan violence during this time period, against what many inhabitants saw as the excesses of ‘carpetbagger’ government. In the 1920’s, Ezra A. Cook published ‘Ku Klux Klan Secrets Exposed’, which gave this example:

“Headquarters, Ninth Division, S. C. Special Orders, No. 3, K. K. K.

Ignorance is the curse of God.

For that reason we are determined that members of the legislature, the school committee and the county commissioners of Union county shall no longer officiate. Fifteen days' notice from this date is given, and if they, and all, do not at once and forever resign their present inhuman, disgraceful and outrageous rule, then retributive justice will as surely be used as night follows day.

By order of the Grand Chief,

A. 0., Grand Secretary.”

The Industrial Revolution hit the county in the 1890s as local businessmen and Northern industrialists began investing in Union County textile mills.[6]

Cotton Mills and industrialization

editThe first cotton mill was built at Lockhart around 1894; it was shortly followed by another in Union and Jonesville. Around 1900, a mill was built west of Union and the town of Buffalo sprang up around it. Workers, or operatives as they were called, lived in company-owned housing and obtained their food and other household goods from the company store. Many workers came from the mountains of North Carolina, where farming was difficult and outside work scarce.[6]

In 1897, the Draytonville and Gowdeysville townships were removed from Union County to form part of Cherokee County.[6]

The turn of the century saw continued progress, as improvements were made in the city of Union and throughout the county. Roads were being paved and the automobile was introduced as new businesses appeared along the Main Street area.[6]

The Great Depression brought difficulties to the mill village, as pay decreased for workers. Meanwhile, in the county's rural areas, farmers suffered much less than those living in the city since they grew most of what they consumed. In the 1930s, the federal government bought large portions of poor quality land in southern Union County and established the Sumter National Forest. This land had been planted in cotton for many years and was overworked. Government programs like the CCC, PWA, and WPA put many Union County residents back to work, and government money helped improve the county's water and sewage plants and public roads. Many Union natives enlisted in the Second World War while developments continued in both urban and rural areas of the county. Cotton production and agricultural acreage was steadily declining and by 1944 Union County was 53 percent "forest land." The automobile had changed the lifestyle of mill workers because now they could drive to work and were no longer required to live in the proximity of the mill villages.[6]

Modern times

editThe post-war years saw the introduction of new industries to the county, such as Torrington and Sonoco. Despite this, the county's economy remained 94 percent textile-related in 1970. In 1955, the U.S. Route 176 bypass (Duncan Bypass) was constructed, along with other road improvements that followed in later years. The Bypass became the center for much of Union's new business, including shopping centers and restaurants. In 1984, work on a four-lane connector to Spartanburg began which would become the Furman Fendley Highway (US 176).[6]

Beginning in the 1980s, many of Union County's textile industries began closing and moving to other countries. The final departure of the textile industry was complete by the 1990s and this left a hole in the county's economy and cultural identity. In recent years, new specialty industries have taken the place of agriculture and textiles; two things that characterized the early history of Union County.[6]

Geography

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 515.44 square miles (1,335.0 km2), of which 513.59 square miles (1,330.2 km2) is land and 1.85 square miles (4.8 km2) (0.36%) is water.[9]

National protected area

edit- Sumter National Forest (part)

State and local protected areas

edit- Rose Hill Plantation State Historic Site

- Sumter National Forest - Enoree Ranger District[10]

- Thurmond Tract Wildlife Management Area[10]

- Wild Turkey Management Demonstration Area[10]

Major water bodies

editAdjacent counties

edit- Cherokee County – north

- York County – northeast

- Chester County – east

- Fairfield County – southeast

- Newberry County – south

- Laurens County – southwest

- Spartanburg County – northwest

Major highways

editDemographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 7,693 | — | |

| 1800 | 10,237 | 33.1% | |

| 1810 | 10,995 | 7.4% | |

| 1820 | 14,126 | 28.5% | |

| 1830 | 17,906 | 26.8% | |

| 1840 | 18,936 | 5.8% | |

| 1850 | 19,852 | 4.8% | |

| 1860 | 19,635 | −1.1% | |

| 1870 | 19,248 | −2.0% | |

| 1880 | 24,080 | 25.1% | |

| 1890 | 25,363 | 5.3% | |

| 1900 | 25,501 | 0.5% | |

| 1910 | 29,911 | 17.3% | |

| 1920 | 30,372 | 1.5% | |

| 1930 | 30,920 | 1.8% | |

| 1940 | 31,360 | 1.4% | |

| 1950 | 31,334 | −0.1% | |

| 1960 | 30,015 | −4.2% | |

| 1970 | 29,230 | −2.6% | |

| 1980 | 30,751 | 5.2% | |

| 1990 | 30,337 | −1.3% | |

| 2000 | 29,881 | −1.5% | |

| 2010 | 28,961 | −3.1% | |

| 2020 | 27,244 | −5.9% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 26,629 | [2] | −2.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] 1790–1960[12] 1900–1990[13] 1990–2000[14] 2010[15] 2020[2] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 17,279 | 63.42% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 8,435 | 30.96% |

| Native American | 56 | 0.21% |

| Asian | 78 | 0.29% |

| Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.01% |

| Other/Mixed | 955 | 3.51% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 438 | 1.61% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 27,244 people, 11,432 households, and 7,701 families residing in the county.

2010 census

editAt the 2010 census, there were 28,961 people, 11,974 households, and 8,095 families residing in the county.[17][15] The population density was 56.3 inhabitants per square mile (21.7/km2). There were 14,153 housing units at an average density of 27.5 per square mile (10.6/km2).[18] The racial makeup of the county was 66.6% white, 31.3% black or African American, 0.3% Asian, 0.2% American Indian, 0.3% from other races, and 1.2% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 1.0% of the population.[17] In terms of ancestry, 13.4% were American, 8.4% were Irish, 6.2% were English, and 5.4% were German.[19]

Of the 11,974 households, 31.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.0% were married couples living together, 19.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 32.4% were non-families, and 29.0% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.90. The median age was 41.9 years.[17]

The median income for a household in the county was $33,470 and the median income for a family was $42,537. Males had a median income of $39,306 versus $26,767 for females. The per capita income for the county was $18,495. About 16.7% of families and 20.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.2% of those under age 18 and 17.1% of those age 65 or over.[20]

Government and politics

editIn 2020, Union County Sheriff David Taylor was charged with misconduct in office and disseminating obscene material, over lewd and obscene texts sent to a county resident.[21]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 8,183 | 61.73% | 4,935 | 37.23% | 139 | 1.05% |

| 2016 | 7,061 | 58.39% | 4,729 | 39.11% | 302 | 2.50% |

| 2012 | 6,584 | 52.50% | 5,796 | 46.22% | 161 | 1.28% |

| 2008 | 7,449 | 54.97% | 5,935 | 43.80% | 167 | 1.23% |

| 2004 | 6,592 | 55.24% | 5,236 | 43.87% | 106 | 0.89% |

| 2000 | 5,768 | 54.47% | 4,662 | 44.03% | 159 | 1.50% |

| 1996 | 3,855 | 38.34% | 5,407 | 53.77% | 793 | 7.89% |

| 1992 | 4,647 | 43.51% | 4,644 | 43.48% | 1,389 | 13.01% |

| 1988 | 6,019 | 57.52% | 4,420 | 42.24% | 26 | 0.25% |

| 1984 | 6,331 | 58.64% | 4,424 | 40.98% | 41 | 0.38% |

| 1980 | 4,035 | 38.59% | 6,274 | 60.00% | 147 | 1.41% |

| 1976 | 3,463 | 35.11% | 6,363 | 64.51% | 37 | 0.38% |

| 1972 | 8,337 | 75.35% | 2,676 | 24.18% | 52 | 0.47% |

| 1968 | 3,011 | 30.50% | 2,271 | 23.00% | 4,590 | 46.50% |

| 1964 | 3,815 | 49.50% | 3,892 | 50.50% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 1,980 | 27.47% | 5,229 | 72.53% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 1,252 | 22.01% | 3,760 | 66.10% | 676 | 11.88% |

| 1952 | 2,094 | 26.13% | 5,921 | 73.87% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 46 | 1.35% | 1,283 | 37.53% | 2,090 | 61.13% |

| 1944 | 33 | 1.05% | 3,041 | 96.48% | 78 | 2.47% |

| 1940 | 29 | 0.79% | 3,662 | 99.21% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 9 | 0.26% | 3,458 | 99.74% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 14 | 0.44% | 3,131 | 99.49% | 2 | 0.06% |

| 1928 | 74 | 2.92% | 2,460 | 97.04% | 1 | 0.04% |

| 1924 | 27 | 1.42% | 1,862 | 98.21% | 7 | 0.37% |

| 1920 | 16 | 0.73% | 2,162 | 99.27% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1916 | 0 | 0.00% | 1,476 | 99.13% | 13 | 0.87% |

| 1912 | 20 | 1.19% | 1,609 | 95.49% | 56 | 3.32% |

| 1904 | 58 | 3.51% | 1,593 | 96.49% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1900 | 91 | 7.15% | 1,182 | 92.85% | 0 | 0.00% |

Economy

editIn 2022, the GDP was $822.7 million (about $30,896 per capita),[23] and the real GDP was $709.5 million (about $26,643 per capita) in chained 2017 dollars.[24]

As of April 2024, some of the top employers of the county include Adecco Staffing, CSL Plasma, Dollar General, Gestamp, Milliken & Company, Sonoco, Spartanburg Regional Healthcare System, Timken Company, University of South Carolina Union, and Walmart.[25]

| Industry | Employment Counts | Employment Percentage (%) | Average Annual Wage ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation and Food Services | 564 | 6.7 | 19,032 |

| Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services | 226 | 2.7 | 32,448 |

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | 30 | 0.4 | 63,908 |

| Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation | 168 | 2.0 | 52,780 |

| Construction | 157 | 1.9 | 54,236 |

| Educational Services | 718 | 8.5 | 62,712 |

| Finance and Insurance | 59 | 0.7 | 34,112 |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 1,842 | 21.7 | 59,644 |

| Information | 138 | 1.6 | 59,280 |

| Management of Companies and Enterprises | 43 | 0.5 | 39,364 |

| Manufacturing | 673 | 7.9 | 45,344 |

| Other Services (except Public Administration) | 54 | 0.6 | 34,736 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 803 | 9.5 | 75,208 |

| Public Administration | 74 | 0.9 | 58,648 |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 89 | 1.0 | 27,612 |

| Retail Trade | 710 | 8.4 | 27,612 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 710 | 8.4 | 60,476 |

| Utilities | 710 | 8.4 | 72,488 |

| Wholesale Trade | 710 | 8.4 | 52,208 |

| Total | 8,478 | 100.0% | 53,645 |

Education

editStudents residing in the county are served by Union County Schools, which operates seven public schools that serve about 4500 students. There is one high school, three kindergarten through 5th grade schools, two kindergarten through 8th grade schools, and one 6th through 8th grade school.[26]

For some time, the county had three high schools, Union High School, Jonesville High School, and Lockhart High School. As of a council ruling, the three high schools have been consolidated. Jonesville High School and Lockhart High School were closed, and the students were reassigned to Union High School, which has been renamed Union County High School.

Union County High School's Yellow Jackets Football team has seen great success in recent past. They won the 4A State Football Championship in 1990 and 1995, and won the 3A State Title in 1999, 2000, and 2002. They were also state runner-up in 2001. The Yellow Jackets were led to their three most recent championships by former head coach and current State Representative Mike Anthony.[27] He retired following the 2004 season. He was succeeded by Tommy Bobo, former Union High School offensive coordinator who left following the 1999 season to become the head football coach at Wren High School. Bobo led the Jackets to the region championship and the state semi-finals in 2005. Bobo resigned in 2007 after the school board decided to consolidate the three high schools. He accepted a position as an assistant at Spartanburg's Dorman High School. Jonesville High School Coach David Lipsey was hired to replace Bobo and be the first coach of Union County High School.

Union County High School's Junior ROTC program is only one of three teams in the nation to ever go four consecutive years to The George C. Marshall Leadership and Academic Bowl in Washington, DC. Members of that team included Michael Leigh, Tommy McKelvey, Micheal Stewart, Lucas Kelley, Ollie Burns, and Mitchell Ward.

The county is also home to a satellite campus of the University of South Carolina. The University of South Carolina campus at Union was opened in 1965 and was once home to the USCU Bantams, a junior college basketball team that saw some success at that level before the team was ended in the 1980s. Since 1965, USC-Union has provided low-cost, fully accredited courses that satisfy the degree requirements at the University of South Carolina and at other colleges and universities. The University of South Carolina at Union enrolls between 300 and 400 students each semester. In addition to associate degrees, USC-Union provides special opportunities such as teacher preparation and access to baccalaureate degrees in interdisciplinary studies.[28]

Union county's Carnegie Library was named Best Small Library in America by Library Journal for 2009.[29]

Communities

editCity

edit- Union (county seat and largest community)

Towns

editCensus-designated places

editUnincorporated communities

editNotable people

edit- John Duff (c. 1759 or c. 1750–June 4, 1799, or c. 1805), counterfeiter, hunter, salt maker, judge, cattle thief, and Revolutionary War soldier

- William Henry Gist (1807–1874), governor of South Carolina from 1858 to 1860

- States Rights Gist (1831–1864), Confederate general in the Civil War

- John William Pearson (1808–1864), businessman and Confederate soldier in the Civil War

- Howard Franklin Jeter (born 1947), retired diplomat[31]

- Susan Smith (born 1971), murderer who killed her two sons and falsely claimed that they were kidnapped by an African-American man; her story gained national attention

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "About". gearupunionsc.com. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts: Union County, South Carolina". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "South Carolina: Individual County Chronologies". South Carolina Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2009. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "OMB Bulletin No. 23-01, Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of Delineations of These Areas" (PDF). United States Office of Management and Budget. July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Charles, Allan D. "The Narrative History of Union County South Carolina" (The Reprint Company, Publishers, 1987)

- ^ Scotch Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America by Charles Knowles Bolton

- ^ a b Union County, South Carolina, court records 1777-1819. 1900. pp. 51–52.

- ^ "2020 County Gazetteer Files – South Carolina". United States Census Bureau. August 23, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c "SCDNR Public Lands". www2.dnr.sc.gov. Retrieved April 1, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Randall, Jon (July 14, 2020). "Suspended Union Co. sheriff turns himself in to detention center after arraignment hearing". FOX Carolina. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (January 1, 2001). "Gross Domestic Product: All Industries in Union County, SC". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (January 1, 2001). "Real Gross Domestic Product: All Industries in Union County, SC". FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ a b "Union County" (PDF). Community Profiles (04000087). Columbia, SC: S.C. Department of Employment & Workforce - Business Intelligence Department. April 19, 2024.

- ^ "Union County Schools". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "SC State House of Representatives". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "University of South Carolina at Union". Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "Best Small Library in America 2009: Union County Carnegie Library, SC—Carolina Dreaming". Library Journal. February 1, 2009. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ "2012 South Carolina Code of Laws :: Title 4 - Counties :: Chapter 3 - Boundaries Of Existing Counties :: Section 4-3-510 - Union County; boundaries of townships".

- ^ "HOWARD FRANKLIN JETER (1947- )". Black Past. February 26, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

External links

edit- Geographic data related to Union County, South Carolina at OpenStreetMap

- Official website