Studium generale is the old customary name for a medieval university in medieval Europe.

Overview edit

There is no official definition for the term studium generale. The term studium generale first appeared at the beginning of the 13th century out of customary usage, and meant a place where students from everywhere were welcomed, not merely those of the local district or region.[1]

In the 13th century, the term gradually acquired a more precise (but still unofficial) meaning as a place that (1) received students from all places, (2) taught the arts and had at least one of the higher faculties (that is, theology, law or medicine) and (3) that a significant part of the teaching was done by those with a master's degree.[2]

A fourth criterion slowly appeared: a master who had taught and was registered in the Guild of Masters of a studium generale was entitled to teach in any other studium without further examination. That privilege, known as jus ubique docendi, was, by custom, reserved only to the masters of the three oldest universities: Salerno, Bologna and Paris. Their reputations were so great that their graduates and teachers were welcome to teach in all other studia, but they accepted no outside teachers without an examination.

Pope Gregory IX, who, seeking to elevate the prestige of the papal-sponsored University of Toulouse, which he had founded in 1229, issued a bull in 1233, allowing Masters of Toulouse to teach in any studium without an examination. It consequently became customary for studia generalia, eager to elevate themselves, to apply for similar bulls. The older universities at first disdained requesting such privileges themselves, feeling their reputation was sufficient. However, Bologna and Paris eventually stooped down to apply for them too, receiving their papal bulls in 1292.[3]

Arguably, the most coveted feature of the papal bulls was the special exemption, instituted by Pope Honorius III in 1219, which allowed teachers and students to continue reaping the fruits of any clerical benefices they might have elsewhere. That dispensed them from the residency requirements set out in canon law.[4] As this privilege was granted only to those in studia generalia, certainly routinely by the 14th century, it began to be considered by many to be not only another (fifth) criterion but the definition of a studium generale . (Although the old universities of Oxford and Padua, which resisted asking for a papal bull, had sufficient reputation to be referred to as studium generale without a bull, Oxford masters were not allowed to teach in Paris without examination. Oxford reciprocated by demanding examinations from Paris masters and ignoring the papal privileges Paris enjoyed.)

Finally, the pope could issue bulls guaranteeing the autonomy of the university from the interference of local civil or diocesan authorities, a process that had begun with the issuing of the 1231 bull for the University of Paris. Although not a necessary criterion, bestowing the "privileges of Paris" to other studia generalia became customary.

The pope was not the only supplier of privileges. The Holy Roman Emperor also issued imperial charters granting much the same privileges, starting with the University of Naples in 1224.

A universal student body, one or more higher faculties, teaching by masters, the right to teach in other studia, retention of benefices, autonomy: those were common features in studia generalia. In other respects (structure, administration, curriculum etc.), studia generalia varied. Generally speaking, most tended to copy one of two old models: the student-centred system of Bologne or the master-centered structure of Paris.

History edit

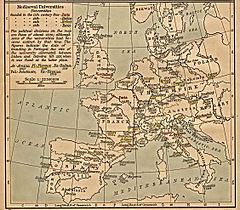

Most of the early studia generalia were found in Italy, France, England, Spain and Portugal, and these were considered the most prestigious places of learning in Europe. The Vatican continues to designate many new universities as studia generalia, although the popular significance of this honour has declined over the centuries.

As early as the 13th century, scholars from a studium generale were encouraged to give lecture courses at other institutes across Europe and to share documents, and this led to the current academic culture seen in modern European universities.

The universities generally considered studia generalia in the 13th century were:

- University of Bologna (founded in 1088)

- University of Oxford (founded in 1167)

- University of Cambridge (founded in 1209)

- University of Palencia (founded in 1212)

- University of Paris (founded in 1215)

- University of Arezzo (founded in 1215)

- University of Salamanca (founded in 1218)

- University of Padua (founded in 1222)

- University of Naples Federico II (founded in 1224)

- University of Toulouse (founded in 1229)

- University of Northampton (founded in 1261, closed in 1265)

- University of Siena (founded in 1240)

- University of Valladolid (founded in 1241)

- University of Salerno (uncertain)

- University of Montpellier (founded in 1289)

- University of Coimbra (founded in Lisbon in 1290)

- University of Alcalá (founded in Alcalá de Henares on May 20, 1293)

Both theological and secular universities were registered. This list quickly grew as new universities were founded throughout Europe. Many of these universities received formal confirmation of their status as studia generalia towards the end of the 13th century by way of papal bull, along with a host of newer universities. While these papal bulls initially did little more than confer the privileges of a specified university such as Bologna or Paris, by the end of the 13th century universities sought a papal bull conferring on them ius ubique docendi, the privilege of granting to masters licences to teach in all universities without further examination (Haskins, 1941:282).

Universities officially recognized as studia generalia in the 14th century were several, among them:

- University of Lleida (founded in 1301)

- Sapienza University of Rome (founded in 1303)

- University of Perugia (founded in 1308)

- University of Florence (founded in 1321)

- University of Pisa (founded in 1343)

- Charles University in Prague (founded in 1348)

- University of Pavia (founded in 1361)

- Jagiellonian University in Kraków (founded in 1364)

- University of Vienna (founded in 1365)

- University of Heidelberg (founded in 1386)

- University of Zadar (founded in 1396)

Contemporary usage edit

Today studium generale is primarily used within a European university context as a description for lectures, seminars and other activities which aim at providing academic foundations for students and the general public. They are in line with the humanistic roots of the traditional universities to reach outside of their boundaries and provide a general education.

In the early post-war years in Germany the concept was re-introduced,[5] for example, with a formal programme begun in 1948 at the Leibniz College[6] of University of Tübingen.

Today the term is often used interchangeably with orientation year and may be regarded as the academic equivalent of a Gap year.

Studium particulare edit

A studium particulare tended to take local students. A studium generale, by contrast, would take students from all regions and all countries.[7]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Rashdall, Hastings. The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages: Salerno. Bologna. Paris. Vol. 1. Clarendon Press, 1895, 8.

- ^ Rashdall, 9.

- ^ Rashdall, 11–12.

- ^ Rashdall, 12.

- ^ Lindegren, Alina M. (1957). Germany Revisited: Education in the Federal Republic. Washington: U. S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Office of Education. p. 107.

- ^ "Das Leibniz Kolleg". Leibniz Kolleg. Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Georgedes, Kimberly. "Religion, Education and the Role of Government in Medieval Universities: Lessons Learned or Lost?." Forum on public policy. Vol. 2. No. 1. 2006. Link.

References edit

- Cobban, Alan, The Medieval Universities: Their Development and Organization, London: Harper & Row, 1975.

- Haskins, George L (1941) 'The University of Oxford and the Ius ubique docendi,' The English Historical Review, pp. 281–292.

- Rashdall, H. (1895) The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages, Vol. 1.