Smaug (/smaʊɡ/[T 1]) is a dragon and the main antagonist in J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel The Hobbit, his treasure and the mountain he lives in being the goal of the quest. Powerful and fearsome, he invaded the Dwarf kingdom of Erebor 171 years[1] prior to the events described in the novel. A group of thirteen dwarves mounted a quest to take the kingdom back, aided by the wizard Gandalf and the hobbit Bilbo Baggins. In The Hobbit, Thorin describes Smaug as "a most specially greedy, strong and wicked worm".[T 2]

| Smaug | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien character | |

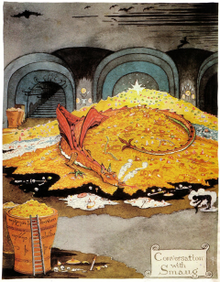

Tolkien's illustration Conversation with Smaug | |

| In-universe information | |

| Race | Dragon |

| Gender | Male |

| Book(s) | |

Critics have identified close parallels with what they presume are sources of Tolkien's inspiration, including the dragon in Beowulf, who is provoked by the stealing of a precious cup, and the speaking dragon Fafnir, who proposes a betrayal to Sigurd.[2] A further source may be Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha, where Megissogwon, the spirit of wealth, is protected by an armoured shirt, but whose one weak spot is revealed by a talking bird.[3] Commentators have noted Smaug's devious, vain, and proud character,[4] and his aggressively polite way of speaking, like the British upper class.[5]

Smaug was voiced and interpreted with performance capture by Benedict Cumberbatch in Peter Jackson's film adaptations of The Hobbit.

Story edit

Dragons lived in the Withered Heath beyond the Grey Mountains. Smaug was "the greatest of the dragons of his day", already centuries old at the time he was first recorded. He heard rumours of the great wealth of the Dwarf-kingdom of Erebor, which had a prosperous trade with the Northmen of Dale. Smaug "arose and without warning came against King Thrór and descended on the mountain in flames". After driving the Dwarves out of their stronghold, Smaug occupied the interior of the mountain for the next 150 years, guarding a vast hoard of treasure. He destroyed the town of Dale; the Men retreated to the Long Lake, where they built Lake-town of houses on stilts, surrounded by water to guard against the dragon.[T 3]

'The King under the Mountain is dead and where are his kin that dare seek revenge? Girion Lord of Dale is dead, and I have eaten his people like a wolf among sheep, and where are his sons' sons that dare approach me? I kill where I wish and none dare resist. I laid low the warriors of old and their like is not in the world today. Then I was but young and tender. Now I am old and strong, strong, strong, Thief in the Shadows!' he gloated. 'My armour is like tenfold shields, my teeth are swords, my claws spears, the shock of my tail a thunderbolt, my wings a hurricane, and my breath death!'

—J. R. R. Tolkien, The Hobbit[6]

Gandalf realized that Smaug could pose a serious threat if used by Sauron. He therefore agreed to assist a party of Dwarves, led by Thrór's grandson Thorin Oakenshield, who set out to recapture the mountain and kill the dragon. Assuming that Smaug would not recognize the scent of a Hobbit, Gandalf recruited Bilbo Baggins to join the quest.[T 4]

Upon reaching Erebor, the Dwarves sent Bilbo into Smaug's lair, and he was initially successful in stealing a beautiful golden cup as Smaug slept. Knowing the contents of the treasure hoard to the ounce, Smaug quickly realized the cup's absence upon awakening and searched for the thief on the Mountain. Unsuccessful, he returned to his hoard to lie in wait. The Dwarves sent Bilbo down the secret tunnel a second time. Smaug sensed Bilbo's presence immediately, even though Bilbo had rendered himself invisible with the One Ring, and accused the Hobbit (correctly) of trying to steal from him. During his discourse with the dragon, Bilbo noticed a small bare patch on Smaug's jewel-encrusted underbelly, and narrowly escaped. A thrush overheard Bilbo's account of the meeting, and learnt of the bare patch on Smaug's underside.[T 5]

Still enraged, Smaug flew south to Lake-town and set about destroying it. The townsmen's arrows and spears proved useless against the dragon's armoured body. The thrush told Bard the Bowman of Smaug's one weak spot, a bare patch on the dragon's belly. With his last arrow, Bard killed Smaug by shooting into this place.[T 6]

Analysis edit

The dragon stopped short in his boasting. 'Your information is antiquated', he snapped. 'I am armoured above and below with iron scales and hard gems. No blade can pierce me.'

'I might have guessed it', said Bilbo. 'Truly there can nowhere be found the equal of Lord Smaug the Impenetrable. What magnificence to possess a waistcoat of fine diamonds!'

'Yes, it is rare and wonderful, indeed', said Smaug absurdly pleased. He did not know that the hobbit had already caught a glimpse of his peculiar under-covering on his previous visit, and was itching for a closer view for reasons of his own. The dragon rolled over. 'Look!' he said. 'What do you say to that?'

'Dazzlingly marvellous! Perfect! Flawless! Staggering!' exclaimed Bilbo aloud, but what he thought inside was: 'Old fool! Why, there is a large patch in the hollow of his left breast as bare as a snail out of its shell!'

—J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit[6]

Character edit

Tolkien made Smaug "more villain than monster", writes the author and biographer Lynnette Porter; he is "devious and clever, vain and greedy, overly confident and proud."[4] The fantasy author Sandra Unerman called Smaug "one of the most individual dragons in fiction".[7] The Tolkien scholar Anne Petty said that "it was love at first sight", describing Smaug as "frightening, but surprisingly knowable".[8]

The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey notes the "bewilderment" that Smaug spreads: he is enchanted by gold and treasure, and those who come into contact with his powerful presence, what Tolkien describes as "the effect that dragon-talk has on the inexperienced", similarly become bewildered by greed.[5] In Shippey's view, however, the most surprising aspect of Smaug's character is "his oddly circumlocutory mode of speech. He speaks in fact with the characteristic aggressive politeness of the British upper class, in which irritation and authority are in direct proportion to apparent deference or uncertainty."[5] In sharp contrast to this is his vanity in response to flattery, rolling over "absurdly pleased" as Tolkien narrates, to reveal his marvellously armoured belly.[5] Shippey comments that such paradoxes, "the oscillations between animal and intelligent behaviour, the contrast between creaking politeness and plain gloating over murder" join to create Smaug's principal attribute, "wiliness".[5]

The Christian commentator Joseph Pearce describes Smaug's weak spot as his Achilles heel, noting his boastful over-confidence in his own indestructibility, and seeing in the fact that the vulnerability is over his heart a sign that "it is the wickedness of his heart which will lead to his downfall".[9] Pearce likens Smaug's pride to that of Achilles, whose pride leads to the death of his best friend, and of many Greeks; and to the cockerel Chauntecleer in Geoffrey Chaucer's "The Nun's Priest's Tale", where a boastful reply to the flattering fox causes the cockerel's fall.[9]

The Beowulf dragon edit

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was a professor of English Literature at Oxford University. He was a prominent scholar of the Old English poem Beowulf, on which he gave a lecture at the British Academy in 1936.[T 7] He described the poem as one of his "most valued sources" for The Hobbit.[T 8] Many of Smaug's attributes and behaviour in The Hobbit derive directly from the unnamed "old night-ravager" in Beowulf: great age; winged, fiery, and reptilian[a] form; a stolen barrow within which he lies on his hoard; disturbance by a theft; and violent revenge on the lands all about, flying and attacking at night.[2]

The scholars of English literature Stuart D. Lee and Elizabeth Solopova analyse the parallels between Smaug and the unnamed Beowulf dragon.[2]

| Plot element | Beowulf | The Hobbit |

|---|---|---|

| Aggressive dragon |

eald uhtsceaða ... hat ond hreohmod ... Wæs þæs wyrmes wig / wide gesyne "old twilight-ravager ... hot and fierce-minded" ... |

Smaug fiercely attacks Dwarves, Laketown |

| Gold-greedy dragon |

hordweard "treasure-guardian" |

Smaug watchfully sleeps on pile of treasure |

| Provoking the dragon |

wæs ða gebolgen / beorges hyrde, wolde se laða / lige forgyldan drincfæt dyre. "was then furious / the barrow's keeper |

Smaug enraged when Bilbo steals golden cup |

| Night-flying dragon |

nacod niðdraca, nihtes fleogeð fyre befangen "naked hate-dragon, flying by night, |

Smaug attacks Laketown with fire, by night |

| Well-protected dragon's lair |

se ðe on heaum hofe / hord beweotode, stanbeorh steapne; stig under læg, eldum uncuð. "the one who on high heath / hoard watched |

Secret passage to Smaug's lair and mound of treasure in stone palace under Mount Erebor |

| Accursed dragon-gold |

hæðnum horde "a heathen hoard" |

The treasure provokes Battle of Five Armies |

Fafnir edit

Smaug's ability to speak, the use of riddles, the element of betrayal, his enemy's communication via birds, and his weak spot could all have been inspired by the talking dragon Fafnir of the Völsunga saga.[7] Shippey identified several points of similarity between Smaug and Fafnir.[2]

| Plot element | Fáfnismál | The Hobbit |

|---|---|---|

| Killing the dragon | Sigurd stabs Fafnir's belly | Bard the Bowman shoots Smaug in the belly |

| Riddling to the dragon | Sigurd does not give his name, but replies in a riddle that he has no mother or father | Bilbo does not give his name, but gives himself riddling names like "clue-finder", "web-cutter", "barrel-rider"[T 5] |

| Dragon suggests betrayal | Fafnir turns Sigurd against Regin | Smaug suggests Bilbo should not trust Dwarves |

| Talking to birds | Dragon-blood lets Sigurd understand bird language: the nuthatches say Regin wants to betray him | A thrush hears Bilbo talk about Smaug's weakness, and tells Bard the Bowman |

Old English spell edit

| Old English | Plain meaning | Alternatively |

|---|---|---|

| smugan, sméogan[11] | "to creep, to squeeze through a hole" | "to think out, to scrutinise" |

| wyrm | "worm" | "lizard, reptile, dragon" |

| "against a crafty dragon" |

Tolkien noted, in a joking letter that he was surprised to see published in The Observer in 1938, that "the dragon bears as name—a pseudonym—the past tense of the primitive Germanic verb smúgan,[11] to squeeze through a hole: a low philological jest."[T 8] Critics have explored what that jest might have been; an 11th-century medical text Lacnunga ("Remedies") contains the Old English phrase wid smeogan wyrme, "against a penetrating worm" in a spell,[12] which could also be translated "against a crafty dragon". The Old English verb meant "to examine, to think out, to scrutinise",[13] implying "subtle, crafty". Shippey comments that it is "appropriate" that Smaug has "the most sophisticated intelligence" in the book.[5] All the same, Shippey notes, Tolkien has chosen the Old Norse verb smjúga, past tense smaug, rather than the Old English sméogan, past tense smeah—possibly, he suggests, because his enemies were Norse dwarves.[14]

The Song of Hiawatha edit

Tolkien's biographer John Garth notes the similarity between Smaug's death from Bard's last arrow and the death of Megissogwon in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha. Megissogwon was the spirit of wealth, protected by an armoured shirt of wampum beads.[b] Hiawatha shoots in vain, until he has only three arrows left. Mama the woodpecker sings to Hiawatha where Megissogwon's only weak point is, the tuft of hair on his head, just as Tolkien's thrush tells Bard where to shoot at Smaug.[3]

Illustrations edit

Tolkien created numerous pencil sketches and two pieces of more detailed artwork portraying Smaug. The latter were a detailed ink and watercolour labelled Conversation with Smaug and a rough coloured pencil and ink sketch entitled Death of Smaug.[16][17][18] While neither of these appeared in the original printing of The Hobbit due to cost constraints, both have been included in subsequent editions, particularly Conversation with Smaug. Death of Smaug was used for the cover of a UK paperback edition of The Hobbit.[19]

Adaptations edit

Animated films edit

A dragon named 'Slag' features in Gene Deitch's brief 1967 animated film.[21]

Francis de Wolff voiced the red dragon in the long-lost 1968 BBC radio dramatization.[22]

Richard Boone voiced Smaug in the 1977 animated film by Rankin/Bass.[23] Austin Gilkeson calls the film's depiction of Smaug "distinctly feline" as he has cat-like eyes and whiskers "and a lush mane".[20] Gilkeson comments that the result does not resemble Western dragons, but that it works well, not least because Smaug's nature as an "intelligent, deadly, greedy" and lazy predator is in his view "very cat-like".[20]

The Hobbit (film series) edit

Smaug was voiced and interpreted with performance capture by Benedict Cumberbatch in Peter Jackson's three-part adaptation of The Hobbit.[24] From the motion capture, Smaug's design was created with key frame animation. Weta Digital employed its proprietary "Tissue" software, which was honoured in 2013 with a "Scientific and Engineering Award" from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to make the dragon as realistic as possible. In addition, Weta Digital supervisor Joe Letteri said in an interview for USA Today that they used classic European and Asian dragons as inspirations to create Smaug.[25] The Telegraph stated that Cumberbatch had "the authority to make of Smaug a cunning nemesis".[26]

In the first film, The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, the audience sees only his legs, wings, and tail, and his eye; the eye is showcased in the final scene of the film. Smaug is a topic of discussion among the White Council as Gandalf's reason to support Thorin Oakenshield's quest.[27]

Smaug appears in the second film, The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug. In an interview with Joe Letteri, Smaug's design was changed to the wyvern-like form shown in the film after the crew saw how Benedict Cumberbatch performed Smaug while moving around on all four limbs.[28]

In The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, Smaug attacks Lake-town. He is killed by Bard with a black arrow and his body falls on the boat carrying the fleeing Master of Lake-town. It is later revealed that Smaug's attack on Erebor was all part of Sauron's design, meaning that Smaug and Sauron were in league with each other.[29][30]

Smaug was considered one of the highlights of the second film of the series; several critics hailed him as cinema's greatest dragon. Critics also praised the visual effects company Weta Digital and Cumberbatch's vocal and motion-capture performance for giving Smaug a fully realized personality, "hiss[ing] out his words with cold-blooded vitriol".[31][32]

Video games edit

In the 2014 video game Lego The Hobbit, the portrayal departs more from the book; rather than ever more closely simulating the book's characters, the scholar Carol L. Robinson notes, the technology has allowed new fiction to be created.[33]

In culture edit

In 2012, Smaug's wealth was estimated at $61 billion, placing him in the Forbes Fictional 15.[34]

In 2011, scientists named a genus of southern African girdled lizards, Smaug.[35] The lizards were so named after the fictional dragon for being armoured, dwelling underground, and native to Tolkien's birthplace, Bloemfontein.[36] In 2015, a new species of shield bug was named Planois smaug, because of its size and its status "sleeping" in the researcher's collections for about 60 years until it was discovered.[37][38]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ The Old English word wyrm, used repeatedly in Beowulf for the flying dragon, has the dictionary meaning of reptile, serpent, or dragon.[10] Tolkien accordingly uses "worm" of Smaug in The Hobbit.[T 9]

- ^ Jeff Thompson drew illustrations of Megissogwon's wampum shirt deflecting arrows for National Geographic.[15]

References edit

Primary edit

- ^ Tolkien 1996, "The Appendix on Languages"

- ^ Tolkien 1937, Chapter 1: An Unexpected Party

- ^ Tolkien 1955, Appendix A:III "Durin's Folk"

- ^ Tolkien 1980, Part III, Chapter 3: The Quest of Erebor

- ^ a b Tolkien 1937, Chapter 12: Inside Information

- ^ Tolkien 1937, Chapter 14: Fire and Water

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983). Tolkien, Christopher (ed.). Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-809019-5.

- ^ a b c Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. #25 to the editor of The Observer, 16 January 1938. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- ^ Tolkien 1937, chapter 1: An Unexpected Party

Secondary edit

- ^ "Timeline/Third Age". Tolkien Gateway. Archived from the original on 24 July 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Shippey's discussion is at Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0261-10401-3.; it is summarized in Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. pp. 109–111. ISBN 978-1-40394-671-3.

- ^ a b Garth, John (9 December 2014). "Tolkien's death of Smaug: American inspiration revealed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ a b Porter, Lynnette (2014). Tarnished Heroes, Charming Villains and Modern Monsters: Science Fiction in Shades of Gray on 21st Century Television. McFarland. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7864-5795-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-0-26110-275-0.

- ^ a b Tolkien 1937, Chapter 12: "Inside Information".

- ^ a b Unerman, Sandra (April 2002). "Dragons in Twentieth Century Fiction". Folklore. 113 (1): 94–101. doi:10.1080/00155870220125462. JSTOR 1261010. S2CID 216644043.

- ^ Petty, Anne C. (2004). Dragons of Fantasy (2nd ed.). Kitsune Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0979270093.

- ^ a b Pearce, Joseph (2012). Bilbo's Journey: Discovering the Hidden Meaning of the Hobbit. Saint Benedict Press. Chapter 10: Dragon Pride Precedeth a Fall. ISBN 978-1-61890-122-4.

- ^ Clark Hall, J. R. (2002) [1894]. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press. p. 365.

- ^ a b Bosworth, Joseph; Bosworth Northcote, T. (2018). "smúgan". An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Prague: Charles University. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Storms, Godfrid (1948). No. 73. [Wið Wyrme] Anglo-Saxon Magic (PDF). 's-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff; D.Litt thesis for University of Nijmegen. p. 303. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

If a man or a beast has drunk a worm ... Sing this charm nine times into the ear, and once an Our Father. The same charm may be sung against a penetrating worm. Sing it frequently on the wound and smear on your spittle, and take green centaury, pound it, apply it to the wound and bathe with hot cow's urine. MS. Harley 585, ff. 136b, 137a (11th century) (Lacnunga).

- ^ Clark Hall, J. R. (2002) [1894]. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary (4th ed.). University of Toronto Press. p. 311.

- ^ Shippey, Tom (13 September 2002). "Tolkien and Iceland: The Philology of Envy". Archived from the original on 14 October 2007.

- ^ Thompson, Jeff (2001). "Hiawatha & Megissogwon". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ "JRR Tolkien artwork on display for first time". BBC. 1 June 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina, eds. (2011). The art of the Hobbit. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00744-081-8.

- ^ "In Focus: The hand-drawn maps from which JRR Tolkien launched Middle-earth". Country Life. 10 August 2018. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ "The Hobbit or There and Back Again by Tolkien, J.R.R. (cover art by J.R.R. Tolkien)". Biblio. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

The Hobbit or There and Back Again by Tolkien, J.R.R. (cover art by J.R.R. Tolkien) London: George Allen & Unwin 1975 Third Edition (Paperback)... 1975... Cover illustration of Death of Smaug

- ^ a b c Gilkeson, Austin (21 December 2018). "Rankin/Bass's The Hobbit Showed Us the Future of Pop Culture". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Lee, Stuart D. (2020). A Companion to J.R.R. Tolkien. Wiley. pp. 518–519. ISBN 9781119656029.

- ^ "The Hobbit Full Cast Radio Drama". Internet Archive. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Harvey, Ryan (29 March 2011). "The Hobbit: The 1977 Animated Television Movie". Black Gate. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (16 June 2011). "Benedict Cumberbatch To Voice Smaug in 'The Hobbit'". Deadline. Los Angeles, California: Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Truitt, Brian (16 December 2013). "Five things to know about scaly 'Hobbit' star Smaug". USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett Company. Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Benedict Cumberbatch's career in pictures: from Hawking to The Child in Time". The Daily Telegraph. 24 September 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike (16 June 2011). "Benedict Cumberbatch To Voice Smaug in 'The Hobbit'". Deadline.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin P. (20 December 2013). "What Happened To Smaug's Other Legs? 'Hobbit' FX Expert Explains". MTV. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Mark (8 December 2013). "Review - 'The Hobbit: The Desolation Of Smaug' Is Middle-Earth Magic". Forbes. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (9 December 2013). "'The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug': It Lives!". Time. Meredith Corporation. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ De Semlyen, Nick (6 December 2013). "The Hobbit: The Desolation Of Smaug Movie Review". Empire. Bauer Media Group. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Wigler, Josh (9 December 2013). "'The Hobbit' Reviews: Get The Scoop On 'Smaug'". Viacom. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- ^ Ashton, Gail (2017). Medieval Afterlives in Contemporary Culture. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-350-02161-7.

- ^ "Smaug". Forbes. 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Protect and Prosper". American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Stanley, Edward L.; Bauer, Aaron M.; Jackman, Todd R.; Branch, William R.; Mouton, P. Le Fras N. (2011). "Between a rock and a hard polytomy: Rapid radiation in the rupicolous girdled lizards (Squamata: Cordylidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (1). Academic Press: 53–70. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.08.024. PMID 20816817.

- ^ Faúndez, Eduardo (19 June 2015). "Patagonian Shield Bug Named After Middle's Earth's Smaug the Dragon". Entomology Today. Annapolis, Maryland: Entomological Society of America. Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ Carvajal, Mariom A.; Faúndez, Eduardo I.; Rider, David A. (2015). "Contribución al conocimiento de los Acanthosomatidae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) de la Región de Magallanes, con descripción de una nueva especie". Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia (Chile). 43 (1): 145–151. doi:10.4067/s0718-686x2015000100013.

Sources edit

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.