Billings Learned Hand (/ˈlɜːrnɪd/ LURN-id; January 27, 1872 – August 18, 1961) was an American jurist, lawyer, and judicial philosopher. He served as a federal trial judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York from 1909 to 1924 and as a federal appellate judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1924 to 1951.

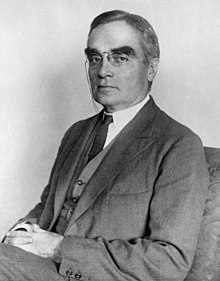

Learned Hand | |

|---|---|

Portrait, c. 1910 | |

| Senior Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |

| In office June 1, 1951 – August 18, 1961 | |

| Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |

| In office September 1, 1948 – June 1, 1951 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Walter Swan |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |

| In office December 20, 1924 – June 1, 1951 | |

| Appointed by | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Julius Marshuetz Mayer |

| Succeeded by | Harold Medina |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York | |

| In office April 26, 1909 – December 29, 1924 | |

| Appointed by | William Howard Taft |

| Preceded by | Seat established by 35 Stat. 685 |

| Succeeded by | Thomas D. Thacher |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Billings Learned Hand January 27, 1872 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | August 18, 1961 (aged 89) New York City, U.S. |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Frances Amelia Fincke

(m. 1902) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Education | Harvard University (AB, AM, LLB) |

Born and raised in Albany, New York, Hand majored in philosophy at Harvard College and graduated with honors from Harvard Law School. After a relatively undistinguished career as a lawyer in Albany and New York City, he was appointed at the age of 37 as a Manhattan federal district judge in 1909. The profession suited his detached and open-minded temperament, and his decisions soon won him a reputation for craftsmanship and authority. Between 1909 and 1914, under the influence of Herbert Croly's social theories, Hand supported New Nationalism. He ran unsuccessfully as the Progressive Party's candidate for chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals in 1913, but withdrew from active politics shortly afterwards. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge elevated Hand to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which he went on to lead as the senior circuit judge (later retitled chief judge) from 1939 until his semi-retirement in 1951. Scholars have recognized the Second Circuit under Hand as one of the finest appeals courts in American history. Friends and admirers often lobbied for Hand's promotion to the Supreme Court, but circumstances and his political past conspired against his appointment.

Hand possessed a gift for the English language, and his writings are admired as legal literature.[1] He rose to fame outside the legal profession in 1944 during World War II after giving a short address in Central Park that struck a popular chord in its appeal for tolerance. During a period when a hysterical fear of subversion divided the nation, Hand was viewed as a liberal defender of civil liberties. A collection of Hand's papers and addresses, published in 1952 as The Spirit of Liberty, sold well and won him new admirers. Even after he criticized the civil-rights activism of the Warren Court, Hand retained his popularity.

Hand is also remembered as a pioneer of modern approaches to statutory interpretation. His decisions in specialist fields—such as patents, torts, admiralty law, and antitrust law—set lasting standards for craftsmanship and clarity. On constitutional matters, he was both a political progressive and an advocate of judicial restraint. He believed in the protection of free speech and in bold legislation to address social and economic problems. He argued that the United States Constitution does not empower courts to overrule the legislation of elected bodies, except in extreme circumstances. Instead, he advocated the "combination of toleration and imagination that to me is the epitome of all good government".[2] As of 2004,[update] Hand had been quoted more often by legal scholars and by the Supreme Court of the United States than any other lower-court judge.[3]

Early life edit

Billings Learned Hand was born on January 27, 1872, in Albany, New York, the second and last child of Samuel Hand (1833–1886) and Lydia Hand (née Learned). His mother's family traditionally used surnames as given names; Hand was named for a maternal uncle and a grandfather, both named Billings Peck Learned.[4] The Hands were a prominent family with a tradition of activism in the Democratic Party. Hand grew up in comfortable circumstances. The family had an "almost hereditary" attachment to the legal profession[5] and has been described as "the most distinguished legal family in northern New York".[6]

Samuel Hand was an appellate lawyer,[7] who had risen rapidly through the ranks of an Albany-based law firm in the 1860s and, by age 32, was the firm's leading lawyer. In 1878, he became the leader of the appellate bar and argued cases before the New York Court of Appeals in "greater number and importance than those argued by any other lawyer in New York during the same period".[8] Samuel Hand was a distant, intimidating figure to his son; Learned Hand later described the relationship with his father as "not really intimate".[9] Samuel Hand died from cancer when Learned was 14.[10] Learned's mother thereafter promoted an idealized memory of her husband's professional success, intellectual abilities, and parental perfection, placing considerable pressure on her son.[11]

Lydia Hand was an involved and protective mother who had been influenced by a Calvinist aunt as a child; she passed on a strong sense of duty and guilt to her only son.[12] Learned Hand eventually came to understand the influences of his parents as formative.[13] After his father's death, he looked to religion to help him cope, writing to his cousin Augustus Noble Hand: "If you could imagine one half the comfort my religion has given to me in this terrible loss, you would see that Christ never forsakes those who cling to him." The depth of Hand's early religious convictions was in sharp contrast to his later agnosticism.[14]

Hand was beset by anxieties and self-doubt throughout his life, including night terrors as a child. He later admitted he was "very undecided, always have been—a very insecure person, very fearful; morbidly fearful".[15] Especially after his father's death, he grew up surrounded by doting women—his mother, his aunt, and his sister Lydia (Lily), eight years his elder.[16] Hand struggled with his name during his childhood and adulthood, worried that "Billings" and "Learned" were not sufficiently masculine. While working as a lawyer in 1899, he ceased using the name "Billings"—calling it "pompous"—and ultimately took on the nickname "B".[7][17]

Hand spent two years at a small primary school before transferring at the age of seven to The Albany Academy, which he attended for the next 10 years. He never enjoyed the Academy's uninspired teaching or its narrow curriculum, which focused on Ancient Greek and Latin, with few courses in English, history, science, or modern languages. Socially, he considered himself an outsider, rarely enjoying recesses or the school's military drills.[18] Vacations, spent in Elizabethtown, New York, were happier times. There, Hand developed a life-long friendship with his cousin and future colleague Augustus Noble Hand, two years his senior.[19] The two were self-confessed "wild boys", camping and hiking in the woods and hills, where Hand developed a love of nature and the countryside.[20] Many years later, when he was in his 70s, Hand recorded several songs for the Library of Congress that he had learned as a boy from Civil War veterans in Elizabethtown.[21] After his father's death, he felt more pressure from his mother to excel academically. He finished near the top of his class and was accepted into Harvard College. His classmates—who opted for schools such as Williams and Yale—thought it as a "stuckup, snobbish school".[22]

Harvard edit

Hand enrolled at Harvard College in 1889, initially focusing on classical studies and mathematics as advised by his late father. At the end of his sophomore year, he changed direction. He embarked on courses in philosophy and economics, studying under the eminent and inspirational philosophers William James, Josiah Royce and George Santayana.[23]

At first, Hand found Harvard a difficult social environment. He was not selected for any of the social clubs that dominated campus life, and he felt this exclusion keenly. He was equally unsuccessful with the Glee Club and the football team; for a time he rowed as a substitute for the rowing club. He later described himself as a "serious boy", a hard worker who did not smoke, drink, or consort with prostitutes.[24] He mixed more in his sophomore and senior years. He became a member of the Hasty Pudding Club and appeared as a blond-wigged chorus girl in the 1892 student musical. He was also elected president of The Harvard Advocate, a student literary magazine.[25]

Hand's studious ways resulted in his election to Phi Beta Kappa, an elite society of scholarly students.[26] He graduated with highest honors, was awarded an Artium Magister degree as well as an Artium Baccalaureus degree,[27] and was chosen by his classmates to deliver the Class Day oration at the 1893 commencement.[26] Family tradition and expectation suggested that he would study law after graduation. For a while, he seriously considered post-graduate work in philosophy, but he received no encouragement from his family or philosophy professors. Doubting himself, he "drifted" toward law.[28]

Hand's three years at Harvard Law School were intellectually and socially stimulating. In his second year, he moved into a boarding house with a group of fellow law students who were to become close friends. They studied hard and enjoyed discussing philosophy and literature and telling bawdy tales. Hand's learned reputation proved less of a hindrance at law school than it had as an undergraduate. He was elected to the Pow-Wow Club, in which law students practiced their skills in moot courts. He was also chosen as an editor of the Harvard Law Review, although he resigned in 1894 because it took too much time from his studies.[29]

During the 1890s, Harvard Law School was pioneering the casebook method of teaching introduced by Dean Christopher Langdell.[30][31] Apart from Langdell, Hand's professors included Samuel Williston, John Chipman Gray, and James Barr Ames. Hand preferred those teachers who valued common sense and fairness, and ventured beyond casebook study into the philosophy of law.[32] His favorite professor was James Bradley Thayer, who taught him evidence in his second year and constitutional law in his third. A man of broad interests, Thayer became a major influence on Hand's jurisprudence. He emphasized the law's historical and human dimensions rather than its certainties and extremes. He stressed the need for courts to exercise judicial restraint in deciding social issues.[33]

Albany legal practice edit

Hand graduated from Harvard Law School with a Bachelor of Laws in 1896 at the age of 24. He returned to Albany to live with his mother and aunt and started work for the law firm in which an uncle, Matthew Hale, was a partner. Hale's unexpected death a few months later obliged Hand to move to a new firm, but by 1899, he had become a partner.[34] He had difficulty attracting his own clients and found the work trivial and dull.[35] Much of his time was spent researching and writing briefs, with few opportunities for the appellate work he preferred. His early courtroom appearances, when they came, were frequently difficult, sapping his fragile self-confidence. He began to fear that he lacked the ability to think on his feet in court.[36]

For two years, Hand tried to succeed as a lawyer by force of will, giving all his time to the practice. By 1900, he was deeply dissatisfied with his progress. For intellectual stimulation, he increasingly looked outside his daily work. He wrote scholarly articles, taught part-time at Albany Law School, and joined a lawyers' discussion group in New York City. He also developed an interest in politics.[37]

Hand came from a line of loyal Democrats, but in 1898 he voted for Republican Theodore Roosevelt as governor of New York. Though he deplored Roosevelt's role in the "militant imperialism" of the Spanish–American War, he approved of the "amorphous mixture of socialism and laisser faire [sic]" in Roosevelt's campaign speeches.[38] Hand caused further family controversy by registering as a Republican for the presidential election of 1900.[39] Life and work in Albany no longer fulfilled him; he began applying for jobs in New York City, despite family pressure against moving.[40]

Marriage and New York edit

After reaching the age of 30 without developing a serious interest in a woman, Hand thought he was destined for bachelorhood. But, during a 1901 summer holiday in the Québec resort of La Malbaie, he met 25-year-old Frances Fincke, a graduate of Bryn Mawr College.[41] Though indecisive in most matters, he waited only a few weeks before proposing. The more cautious Fincke postponed her answer for almost a year, while Hand wrote to and occasionally saw her. He also began to look more seriously for work in New York City.[42] The next summer, both Hand and Fincke returned to La Malbaie, and at the end of August 1902, they became engaged and kissed for the first time.[43] They married on December 6, 1902, shortly after Hand had accepted a post with the Manhattan law firm of Zabriskie, Burrill & Murray.[44] The couple had three daughters: Mary Deshon (born 1905), Frances (born 1907), and Constance (born 1909). Hand proved an anxious husband and father. He corresponded regularly with his doctor brother-in-law about initial difficulties in conceiving and about his children's illnesses. He survived pneumonia in February 1905, taking months to recover.[45]

The family at first spent summers in Mount Kisco, with Hand commuting on the weekends. After 1910, they rented summer homes in Cornish, New Hampshire, a writers' and artists' colony with a stimulating social scene. The Hands bought a house there in 1919, which they called "Low Court".[46] As Cornish was a nine-hour train journey from New York, the couple were separated for long periods. Hand could join the family only for vacations.[47] The Hands became friends of the popular artist Maxfield Parrish, who lived in nearby Plainfield. The Misses Hand posed for some of his paintings.[48]

The Hands also became close friends of Cornish resident Louis Dow, a Dartmouth College professor. Frances Hand spent increasing amounts of time with Dow while her husband was in New York, and tension crept into the marriage. Despite speculation, there is no evidence that she and Dow were lovers. Hand regretted Frances' long absences and urged her to spend more time with him, but he maintained an enduring friendship with Dow.[49] He blamed himself for a lack of insight into his wife's needs in the early years of the marriage, confessing his "blindness and insensibility to what you wanted and to your right to your own ways when they differed from mine".[50] Fearing he might otherwise lose her altogether, Hand came to accept Frances' desire to spend time in the country with another man.[50]

While staying in Cornish in 1908, Hand began a close friendship with the political commentator and philosopher Herbert Croly.[51] At the time, Croly was writing his influential book The Promise of American Life, in which he advocated a program of democratic and egalitarian reform under a national government with increased powers.[52] When the book was published in November 1909, Hand sent copies to friends and acquaintances, including former president Theodore Roosevelt.[53] Croly's ideas had a powerful effect on Roosevelt's politics, influencing his advocacy of New Nationalism and the development of Progressivism.[54]

Hand continued to be disappointed in his progress at work. A move to the firm of Gould & Wilkie in January 1904 brought neither the challenges nor the financial rewards for which he had hoped.[55] "I was never any good as a lawyer," he later admitted. "I didn't have any success, any at all."[56] In 1907, deciding that at the age of 35 success as a Wall Street lawyer was out of reach, he lobbied for a potential new federal judgeship in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, the federal court headquartered in Manhattan. He became involved briefly in local Republican politics to strengthen his political base. In the event, Congress did not create the new judgeship in 1907; but, when the post was finally created in 1909, Hand renewed his candidacy. With the help of the influential Charles C. Burlingham, a senior New York lawyer and close friend, he gained the backing of Attorney General George W. Wickersham, who urged President William Howard Taft to appoint Hand. One of the youngest federal judges ever appointed, Hand took his judicial oath at age 37 in April 1909.[57]

Federal judge edit

Hand served as a United States district judge in the Southern District of New York from 1909 to 1924. He dealt with fields of common law, including torts, contracts, and copyright, and admiralty law. His unfamiliarity with some of these specialties, along with his limited courtroom experience, caused him anxiety at first.[58] Most of Hand's early cases concerned bankruptcy issues, which he found tiresome, and patent law, which fascinated him.[59]

Hand made some important decisions in the area of free speech. A frequently cited 1913 decision is United States v. Kennerley,[60] an obscenity case concerning Daniel Carson Goodman's Hagar Revelly, a social-hygiene novel about the "wiles of vice," which had caught the attention of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.[61] Hand allowed the case to go forward on the basis of the Hicklin test, which stemmed back to a seminal English decision of 1868, Regina v. Hicklin.[62] In his opinion, Hand recommended updating the law, arguing that the obscenity rule should not simply protect the most susceptible readers but should reflect community standards:

It seems hardly likely that we are even to-day so lukewarm in our interest in letters or serious discussion as to be content to reduce our treatment of sex to the standard of a child's library in the supposed interest of a salacious few, or that shame will for long prevent us from adequate portrayal of some of the most serious and beautiful sides of human nature.[63]

Hand was politically active in the cause of New Nationalism.[64] With reservations, in 1911 he supported Theodore Roosevelt's return to national politics. He approved of the ex-president's plans to legislate on behalf of the underprivileged and to control corporations, as well as of his campaign against the abuse of judicial power.[65] Hand sought to influence Roosevelt's views on these subjects, both in person and in print, and wrote articles for Roosevelt's magazine, The Outlook.[66] His hopes of swaying Roosevelt were often dashed. Roosevelt's poor grasp of legal issues particularly exasperated Hand.[67]

Despite overwhelming support for Roosevelt in the primaries and polls, the Republicans renominated the incumbent President Taft. A furious Roosevelt bolted from the party to form the Progressive Party, nicknamed the "Bull Moose" movement. Most Republican progressives followed him, including Hand.[68] The splitting of the Republican vote harmed both Roosevelt's and Taft's chances of winning the 1912 presidential election. As Hand expected, Roosevelt lost to the Democratic Party's Woodrow Wilson, though he polled more votes than Taft.[69]

Hand took the defeat in his stride. He considered the election merely as a first step in a reform campaign for "real national democracy".[70] Though he had limited his public involvement in the election campaign, he now took part in planning a party structure.[71] He also accepted the Progressive nomination for chief judge of New York Court of Appeals, then an elective position, in September 1913.[72] He refused to campaign, and later admitted that "the thought of harassing the electorate was more than I could bear".[73] His vow of silence affected his showing, and he received only 13% of the votes.[74] Hand came to regret his candidacy: "I ought to have lain off, as I now view it; I was a judge and a judge has no business to mess into such things."[75]

By 1916, Hand realized that the Progressive Party had no future, as the liberal policies of the Democratic government were making much of its program redundant. Roosevelt's decision not to stand in the 1916 presidential election dealt the party its death blow.[77] Hand had already turned to an alternative political outlet in Herbert Croly's The New Republic, a liberal magazine which he had helped launch in 1914.[78] Hand wrote a series of unsigned articles for the magazine on issues of social reform and judicial power; his only signed article was "The Hope of the Minimum Wage", published in November 1916, which called for laws to protect the underprivileged. Often attending staff dinners and meetings, Hand became a close friend of the gifted young editor Walter Lippmann.[79] The outbreak of World War I in 1914 had coincided with the founding of the magazine, whose pages often debated the events in Europe. The New Republic adopted a cautiously sympathetic stance towards the Allies, which Hand supported wholeheartedly. After the United States entered the war in 1917, Hand considered leaving the bench to assist the war effort. Several possible war-related positions were suggested to him. Nothing came of them, aside from his chairing a committee on intellectual property law that suggested treaty amendments for the Paris Peace Conference.[80]

Hand made his most memorable decision of the war in 1917 in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten.[81] After the country joined the war, Congress had enacted an Espionage Act that made it a federal crime to hinder the war effort. The first test of the new law came two weeks later when the postmaster of New York City refused to deliver the August issue of The Masses, a self-described "revolutionary journal". The edition contained drawings, cartoons, and articles criticizing the government's decision to go to war.[82]

The publishing company sought an injunction to prevent the ban, and the case came before Judge Hand.[83] In July 1917, he ruled that the journal should not be barred from distribution through the mail. Though The Masses supported those who refused to serve in the forces, its text did not, in Hand's view, tell readers that they must violate the law. Hand argued that suspect material should be judged on what he called an "incitement test": only if its language directly urged readers to violate the law was it seditious—otherwise freedom of speech should be protected.[84] This focus on the words themselves, rather than on their effect, was novel and daring; but Hand's decision was promptly stayed, and later overturned on appeal.[85] He always maintained that his ruling had been correct. Between 1918 and 1919, he attempted to convince Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., a man he greatly admired, of his argument. His efforts at first appeared fruitless, but Holmes' dissenting opinion in Abrams v. United States in November 1919 urged greater protection of political speech.[86] Scholars have credited the critiques of Hand, Ernst Freund, Louis Brandeis, and Zechariah Chafee for the change in Holmes's views.[87] In the long-term, Hand's decision proved a landmark in the history of free speech in the country.[88] In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the Supreme Court announced a standard for protecting free speech that in effect recognized his Masses opinion as law.[89]

Hand had known that ruling against the government might harm his prospects of promotion.[90] By the time of the case, he was already the most senior judge of his district. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit often summoned him to sit with that court to hear appeals, a task he found stimulating. In 1917, he lobbied for promotion to the Second Circuit, but the unpopularity of his Masses decision and his reputation as a liberal stood against him. He was passed over in favor of Martin T. Manton.[91]

In the final months of the war, Hand increasingly supported President Woodrow Wilson's post-war foreign policy objectives. He believed the United States should endorse the League of Nations and the Treaty of Versailles, despite their flaws. This position estranged him from Croly and others at The New Republic, who vehemently rejected both. Alienated from his old circle on the magazine and by the reactionary and isolationist mood of the country, Hand found himself politically homeless.[92]

Between the wars edit

The next Second Circuit vacancy arose in 1921, but with the conservative Warren G. Harding administration in power, Hand did not put himself forward. Nonetheless, Hand's reputation was such that by 1923, Justice Holmes wanted him on the Supreme Court,[93] and in 1924 Harding's successor, Calvin Coolidge, appointed Hand to the Second Circuit. It was a sign of Hand's increased stature that figures such as Coolidge and Chief Justice William Howard Taft now endorsed him. Coolidge sought to add new blood to a senior judiciary that was seen as corrupt and inefficient.[94] In 1926 and 1927, the Second Circuit was strengthened by the appointments of Thomas Walter Swan and Hand's cousin Augustus Noble Hand.[95]

After the demise of the Progressive Party, Hand had withdrawn from party politics.[30] He committed himself to public impartiality, despite his strong views on political issues. He remained a strong supporter of freedom of speech, and any sign of the "merry sport of Red-baiting" troubled him. In 1920, for example, he wrote in support of New York Governor Al Smith's veto of the anti-sedition Lusk Bills. The New York Assembly had approved these bills in a move to bar five elected Socialist Party legislators from taking their seats.[96] In 1922, Hand privately objected to a proposed limit on the number of Jewish students admitted to Harvard College. "If we are to have in this country racial divisions like those in Europe," he wrote, "let us close up shop now".[97]

In public, Hand discussed issues of democracy, free speech, and toleration only in general terms. This discretion, plus a series of impressive speaking engagements, won him the respect of legal scholars and journalists,[98] and by 1930 he was viewed as a serious candidate for a seat on the Supreme Court. His friend Felix Frankfurter, then a Harvard Law School professor, was among those lobbying hard for Hand's appointment. President Herbert Hoover chose to bypass him, possibly for political reasons, and appointed Charles Evans Hughes, who had previously served on the Court for six years before resigning to become the Republican nominee for President in 1916, as Chief Justice. With Hughes and another New Yorker, Harlan Fiske Stone, on the Court, the promotion of a third New Yorker was then seen as impossible.[99]

Hand had voted for Hoover in 1928, and he did so again in 1932; but in 1936, he voted for the Democrats and Franklin D. Roosevelt as a reaction to the economic and social turmoil that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929. With the Great Depression setting in, Hand favored a policy of interventionist central government. He came to accept Frankfurter's view that redistribution of wealth was essential for economic recovery. Hoover resisted this approach, favoring individualism and free enterprise. Roosevelt, on the other hand, promised the voters a New Deal. They elected him on a platform of strong executive leadership and radical economic reform. Hand voted for Roosevelt again in 1940 and 1944, but he remained vigilant on the constitutional dangers of big government.[100] Like others, including Walter Lippmann, he sensed the dictatorial potential of New Deal policies. He had no hesitation in condemning Roosevelt's 1937 bill to expand the Supreme Court and pack it with New Dealers.[101]

Hand was increasingly called upon to judge cases arising from the flood of New Deal legislation. The line between central government authority and local legislation particularly tested his powers of judgment. In 1935, the case of United States v. Schechter came before the Second Circuit.[102] Hand and his two colleagues had to judge whether a New York poultry firm had contravened New Deal legislation on unfair trade practices. They ruled that the National Industrial Recovery Act did not apply to the Schechter Poultry Corporation, which traded solely within the state. "The line is no doubt in the end arbitrary," Hand wrote in a memorandum, "but we have got to draw it, because without it Congress can take over all the government."[103] The Supreme Court later affirmed Hand's decision.

Hand became an acknowledged expert on New Deal statutes. He relished the challenge of interpreting such legislation, calling it "an act of creative imagination".[104] In a 1933 broadcast, he explained the balancing act required of a judge in interpreting statutes:

On the one hand he must not enforce whatever he thinks best; he must leave that to the common will expressed by the government. On the other, he must try as best he can to put into concrete form what that will is, not by slavishly following the words, but by trying honestly to say what was the underlying purpose expressed.[105]

World War II edit

When war broke out in Europe in 1939, Learned Hand adopted an anti-isolationist stance. He rarely spoke out publicly, not only because of his position but because he thought bellicosity unseemly in an old man.[106] In February 1939, he became his court's senior circuit leader (in effect, chief judge, although the title was not created until 1948). In this post, Hand succeeded Martin Manton, who had resigned after corruption allegations that later led to Manton's criminal conviction for bribery.[107] Not an admirer of Manton, Hand nonetheless testified at his trial that he had never noticed any corrupt behavior in his predecessor. Having sat in two cases in which Manton accepted bribes, Hand worried for years afterward that he should have detected his colleague's corruption.[108]

Hand still regarded his main job as judging. As circuit leader, he sought to free himself and his judges from too great an administrative burden. He concentrated on maintaining good relations with his fellow judges and on cleansing the court of patronage appointments. Despite the Manton case and constant friction between two of the court's judges, Charles Edward Clark and Jerome Frank, the Second Circuit under Hand earned a reputation as one of the best appeal courts in the country's history.[109]

In 1942, Hand's friends once again lobbied for him to fill a Supreme Court vacancy, but Roosevelt did not appoint him. The president gave age as the reason, but philosophical differences with Hand may also have played a part.[110] Another explanation lies in one of Justice William O. Douglas's autobiographies, where Douglas states that, despite Roosevelt's belief that Hand was the best person for the job, Roosevelt had been offended by the pressure Justice Felix Frankfurter placed on the president during a vigorous letter-writing campaign on Hand's behalf.[111] D.C. circuit judge Wiley Blount Rutledge, whom Roosevelt appointed, died in 1949, while Hand lived until 1961.[112] In a February 1944 correspondence with Frankfurter, Hand expressed a low opinion of Roosevelt's new appointees, referring to Justice Hugo Black, Justice Douglas, and Justice Frank Murphy as "Hillbilly Hugo, Good Old Bill, and Jesus lover of my Soul".[113] Deeply disappointed at the time, Hand later regretted his ambition: "It was the importance, the power, the trappings of the God damn thing that really drew me on."[114][115]

Hand was relieved when the United States entered the war in December 1941. He felt free to participate in organizations and initiatives connected with the war effort, and was particularly committed to programs in support of Greece and Russia. He backed Roosevelt for the 1944 election, partly because he feared a return to isolationism and the prolonging of the wartime erosion of civil liberties.[116] In 1943, the House Un-American Activities Committee or "Dies Committee", for example, had aroused his fears with an investigation into "subversive activities" by government workers. Hand's contemporary at Harvard College, Robert Morss Lovett, was one of those accused, and Hand spoke out on his behalf.[117] As the end of the war approached, there was much talk of international peace organizations and courts to prevent future conflict, but Hand was skeptical. He also condemned the Nuremberg war-crimes trials, which he saw as motivated by vengeance; he did not believe that "aggressive war" could be construed as a crime. "The difference between vengeance and justice," he wrote later, "is that justice must apply to all."[118]

Hand had never been well known to the general public, but a short speech he made in 1944 won him fame and a national reputation for learnedness that lasted until the end of his life.[98] On May 21, 1944, he addressed almost one and a half million people in Central Park, New York, at the annual "I Am an American Day" event, where newly naturalized citizens swore the Pledge of Allegiance.[119] He stated that all Americans were immigrants who had come to America in search of liberty. Liberty, he said, was not located in America's constitutions, laws, and courts, but in the hearts of the people. In what would become the speech's most quoted passage, Hand asked:

What then is the spirit of liberty? I cannot define it; I can only tell you my own faith. The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the minds of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias; the spirit of liberty remembers that not even a sparrow falls to earth unheeded; the spirit of liberty is the spirit of Him who, near two thousand years ago, taught mankind that lesson it has never learned, but has never quite forgotten; that there may be a kingdom where the least shall be heard and considered side by side with the greatest.[120]

Extracts of the speech appeared in The New Yorker on June 10. Several weeks later, The New York Times printed the whole text. Life magazine and Reader's Digest followed soon after.[98] Hand's message that liberty is safeguarded by everyday Americans struck a popular chord, and he suddenly found himself a folk hero.[121] Though he enjoyed the acclaim, he thought it unmerited. His biographer Gerald Gunther, noting the paradox of the agnostic Hand's use of religious overtones, suggests that the most challenging aspect of the speech was that the spirit of liberty must entertain doubt.[122]

Postwar years edit

Learned Hand's 75th birthday in 1947 was much celebrated in the press and in legal circles. C. C. Burlingham, Hand's former sponsor, for example, called him "now unquestionably the first among American judges".[123] Hand remained modest in the face of such acclaim. He continued to work as before, combining his role as presiding judge of the Second Circuit with his engagement in political issues. In 1947, he voiced his opposition to a proposed "group libel" statute that would have banned defamation of racial or minority groups. He argued that such a law would imply that intolerance could base itself upon evidence. The effect of the proposed prosecutions, he said, would be "rather to exacerbate than to assuage the feelings which lie behind the defamation of groups".[124]

The Cold War and McCarthyism edit

In the postwar period, Hand shared the dismay of his compatriots about Stalinism and the onset of the Cold War. At the same time, he was sensitive to the domestic problems created by what he saw as a hysterical fear of international Communism. Already in 1947, he noted that "the frantic witch hunters are given free rein to set up a sort of Inquisition, detecting heresy wherever non-conformity appears".[125] He was distressed by the crusade against domestic subversion that had become part of American public life after the war.[126]

Hand particularly despised the anti-Communist campaign of Senator Joseph McCarthy that began in 1950 and which became known as McCarthyism. Though Hand expressed his horror of McCarthyism privately, he hesitated to do so publicly because cases arising from it were likely to come before his court.[127]

Coplon, Dennis, and Remington cases edit

During this period, Hand took part in three cases that posed a particular challenge to his impartiality on Cold War issues: United States v. Coplon, Dennis v. United States, and United States v. Remington.[128]

Department of Justice worker Judith Coplon had been sentenced to 15 years in prison for stealing and attempting to pass on defense information. In 1950, her appeal came before a Second Circuit panel that included Learned Hand. It rested on her claim that her rights under the Fourth Amendment had been infringed by a warrantless search, and that details of illegal wiretaps had not been fully disclosed at trial. Although Hand was unambiguous in his view Coplon had been guilty of the charges against her, he nonetheless rejected the trial judge's conclusion that a warrantless arrest had been justified. He ruled therefore that papers seized during the arrest had been inadmissible as evidence.[129] The trial judge's failure to disclose all the wiretap records, Hand concluded, necessitated a reversal of Coplon's conviction. In his opinion, Hand wrote: "[F]ew weapons in the arsenal of freedom are more useful than the power to compel a government to disclose the evidence on which it seeks to forfeit the liberty of its citizens."[130] Hand received hate mail after this decision.

Hand's position in the 1950 case Dennis v. United States contrasted sharply with his Coplon opinion. In Dennis, Hand affirmed the convictions under the 1940 Smith Act of eleven leaders of the Communist Party of the United States for subversion. He ruled that calls for the violent overthrow of the American government posed enough of a "probable danger" to justify the invasion of free speech.[131] After the ruling, he was attacked from the other political direction for appearing to side with McCarthyism.[132]

In 1953, Hand wrote a scathing dissent from a Second Circuit decision affirming the perjury conviction of William Remington, a government economist accused of Communist sympathies and activities. In 1951, the same panel had originally overturned Remington's conviction for perjury. Rather than retrying Remington on their original perjury charges, the government instead brought new perjury charges based on his testimony at the first trial. He was convicted of two charges. In the latter appeal, Hand was outvoted two to one. The prosecution produced stronger evidence against Remington at the second trial, much of it obtained from his wife. Sentenced to three years' imprisonment, Remington was murdered in November 1954 by two fellow inmates, who beat him over the head with a brick wrapped in a sock. According to Hand's biographer Gunther, "The image of Remington being bludgeoned to death in prison haunted Hand for the rest of his life."[133]

Public opposition to McCarthyism edit

Only after stepping down from his position as a full-time judge in 1951 did Hand join the public debate on McCarthyism. Shortly after his semi-retirement, he gave an unscripted speech that was published in The Washington Post, an anti-McCarthy newspaper. Hand wrote:

[M]y friends, will you not agree that any society which begins to be doubtful of itself; in which one man looks at another and says: "He may be a traitor," in which that spirit has disappeared which says: "I will not accept that, I will not believe that—I will demand proof. I will not say of my brother that he may be a traitor," but I will say, "Produce what you have. I will judge it fairly, and if he is, he shall pay the penalties; but I will not take it on rumor. I will not take it on hearsay. I will remember that what has brought us up from savagery is a loyalty to truth, and truth cannot emerge unless it is subjected to the utmost scrutiny"—will you not agree that a society that has lost sight of that, cannot survive?[134]

Hand followed this up with an address to the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York the next year. Once again, his attack on McCarthyism won approval from many liberals. Asked to send a copy of his views to McCarthy, Hand replied that he had Richard Nixon in mind as well.[135] Despite his concerns about Nixon as vice president, Hand voted for Dwight Eisenhower in the 1952 election and later credited Eisenhower with bringing about McCarthy's downfall in 1954.[136]

Semi-retirement and death edit

In 1951, Hand retired from "regular active service" as a federal judge.[137] He assumed senior status, a form of semi-retirement, and continued to sit on the bench, with a considerable workload.[138] The following year, he published The Spirit of Liberty, a collection of papers and addresses that neither he nor publisher Alfred A. Knopf expected to make a profit. In fact, the book earned admiring reviews, sold well, and made Hand more widely known.[98] A 1958 paperback edition sold even better, though Hand always refused royalties from material he never intended for publication.[139]

Louis Dow had died in 1944, with Frances Hand at his side. The Hands' marriage then entered its final, happiest phase, in which they rediscovered their first love.[140] He was convinced that his wife had rescued him from a life as a "melancholic, a failure [because] I should have thought myself so, and probably single and hopelessly hypochondriac".[141]

Former law clerks have provided intimate details of Hand's character during the last decade of his life. Legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin recalls that Hand, scrupulous about public economy, used to turn out the lights in all the offices at the end of each day. For the same reason, he refused Dworkin the customary month's paid vacation at the end of his service. Shortly afterward, to Dworkin's surprise, Hand wrote him a personal check for an extra month's pay as a wedding present.[142] Hand was known for his explosive temper. Gunther remembers him throwing a paperweight in his direction which narrowly missed.[143] Hand had a habit of turning his seat 180° on lawyers whose arguments annoyed him, and he could be bitingly sarcastic. In a typical memo, he wrote, "This is the most miserable of cases, but we must dispose of it as though it had been presented by actual lawyers."[144] Despite such outbursts, Hand was deeply insecure throughout his life, as he fully recognized.[145] In his 80s, he still fretted about his rejection by the elite social clubs at Harvard College.

Learned Hand remained in good physical and mental condition for most of the last decade of his life. In 1958, he gave the Holmes Lectures at Harvard Law School. These lectures proved to be Hand's last major critique of judicial activism, a position he had first taken up in 1908 with his attack on the Lochner ruling.[146] They included a controversial attack on the Warren Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which in Hand's opinion had exceeded its powers by overruling Jim Crow segregation laws.[147] His views were widely criticized as reactionary and unfortunate, with most deploring the fact that they might encourage segregationists who opposed libertarian judicial rulings. Published as The Bill of Rights, the lectures nevertheless became a national bestseller.[148]

The Catcher in the Rye author J. D. Salinger became a neighbor in Cornish, New Hampshire in 1953, and Hand became Salinger's best and almost only friend as Salinger become more and more reclusive.[149][150]

By 1958, Hand was suffering from intense pain in his back and faced difficulty in walking. "I can just manage, with not infrequent pauses, to walk about a third of a mile," he wrote to Felix Frankfurter. "My feet get very numb and my back painful. The truth is that 86 is too long."[151] Soon, he was obliged to use crutches, but he remained mentally sharp and continued to hear cases. In 1960, he worked briefly on President Dwight Eisenhower's "Commission on National Goals", but he resigned because "it involved more work than in the present state of my health I care to add to the judicial work that I am still trying to do".[152]

By June 1961, Hand was in a wheelchair. He joked that he felt idle because he had taken part in no more than about 25 cases that year, and that he would start another job if he could find one.[153] The following month, he suffered a heart attack at Cornish. He was taken to St Luke's Hospital in New York City, where he died peacefully on August 18, 1961. The New York Times ran a front-page obituary. The Times of London wrote: "There are many who will feel that with the death of Learned Hand the golden age of the American judiciary has come to an end."[154]

He was buried next to his wife in the family plot at Albany Rural Cemetery near Menands, New York.[155]

Philosophy edit

Hand's study of philosophy at Harvard left a lasting imprint on his thought. As a student, he lost his faith in God, and from that point on he became a skeptic.[156] Hand's view of the world has been identified as relativistic; in the words of scholar Kathryn Griffith, "[i]t was his devotion to a concept of relative values that prompted him to question opinions of the Supreme Court which appeared to place one value absolutely above the others, whether the value was that of individual freedom or equality or the protection of young people from obscene literature."[157] Hand instead sought objective standards in constitutional law, most famously in obscenity and civil liberties cases.[158] He saw the Constitution and the law as compromises to resolve conflicting interests, possessing no moral force of their own.[159] This denial that any divine or natural rights are embodied in the Constitution led Hand to a positivistic view of the Bill of Rights.[160] In this approach, provisions of the Constitution, such as freedom of press, freedom of speech, and equal protection, should be interpreted through their wording and in the light of historical analysis rather than as "guides on concrete occasions".[161] For Hand, moral values were a product of their times and a matter of taste.[157]

Hand's civil instincts were at odds with the duty of a judge to stay aloof from politics.[162] As a judge he respected even bad laws; as a member of society he felt free to question the decisions behind legislation. In his opinion, members of a democratic society should be involved in legislative decision-making.[163] He therefore regarded toleration as a prerequisite of civil liberty. In practice, this even meant that those who wish to promote ideas repugnant to the majority should be free to do so, within broad limits.[164]

Hand's skepticism extended to his political philosophy, once describing himself as "a conservative among liberals, and a liberal among conservatives".[165] As early as 1898, he rejected his family's Jeffersonian Democratic tradition.[166] His thoughts on liberty, collected in The Spirit of Liberty (1952), began by recalling the political philosophies of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton.[167] Jefferson believed that each individual has a right to freedom, and that government, though necessary, threatens that freedom. In contrast, Hamilton argued that freedom depends on government: too much freedom leads to anarchy and the tyranny of the mob.[168] Hand, who believed, following Thomas Hobbes, that the rule of law is the only alternative to the rule of brutality,[169] leaned towards Hamilton.[170] Since the freedom granted to the American pioneers was no longer feasible,[171] he accepted that individual liberty should be moderated by society's norms.[172] He nevertheless saw the liberty to create and to choose as vital to peoples' humanity and entitled to legal protection. He assumed the goal of human beings to be the "good life", defined as each individual chooses.[173]

Between 1910 and 1916, Hand tried to translate his political philosophy into political action. Having read Croly's The Promise of American Life and its anti-Jeffersonian plea for government intervention in economic and social issues, he joined the Progressive Party.[174] He discovered that party politicking was incompatible not only with his role as a judge but with his philosophical objectivity. The pragmatic philosophy Hand had imbibed from William James at Harvard required each issue to be individually judged on its merits, without partiality. In contrast, political action required partisanship and a choice between values.[174] After 1916, Hand preferred to retreat from party politics into a detached skepticism. His belief in central planning resurfaced during the 1930s in his growing approval of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, as he once again—though this time as an observer—endorsed a program of government intervention.[175] Hand was also an interventionist on foreign policy, supporting U.S. involvement in both world wars, and disdained isolationism.[176]

Jurisprudence edit

Hand has been called one of the United States' most significant judicial philosophers.[177] A leading advocate of judicial restraint, he took seriously Alexander Hamilton's formulation that "the judiciary ... may truly be said to have neither force nor will, but merely judgement."[178] Any judicial ruling that had the effect of legislating from the bench troubled Hand. In 1908, in his article "Due Process of Law and the Eight-Hour Day", he attacked the 1905 Supreme Court ruling in Lochner v. New York, which had struck down a law prohibiting bakery staff from working more than ten hours a day. The Supreme Court went on to strike down a series of similar worker-protective laws on the grounds that they restricted freedom of contract.[179] Hand regarded this principle as undemocratic.[180] "For the state to intervene", he argued, "to make more just and equal the relative strategic advantages of the two parties to the contract, of whom one is under the pressure of absolute want, while the other is not, is as proper a legislative function as that it should neutralize the relative advantages arising from fraudulent cunning or from superior force."[181]

The issue concerned Hand again during the New Deal period, when the Supreme Court repeatedly overturned or blocked Franklin D. Roosevelt's legislation.[182] As an instinctive democrat, Hand was appalled that an elected government should have its laws struck down in this way. He viewed it as a judicial "usurpation" for the Supreme Court to assume the role of a third chamber in these cases.[183] As far as he was concerned, the Constitution already provided a full set of checks and balances on legislation.[184] Nevertheless, Hand did not hesitate to condemn Roosevelt's frustrated attempt to pack the Supreme Court in 1937,[185] which led commentators to warn of totalitarianism. The answer, for Hand, lay in the separation of powers: courts should be independent and act on the legislation of elected governments.[186]

Hand's democratic respect for legislation meant that he hardly ever struck down a law.[187] Whenever his decisions went against the government, he based them only on the boundaries of law in particular cases. He adhered to the doctrine of presumptive validity, which assumes that legislators know what they are doing when they pass a law.[188] Even when a law was uncongenial to him, or when it seemed contradictory, Hand set himself to interpret the legislative intent.[189] Sometimes he was obliged to draw the line between federal and state laws, as in United States v. Schechter Poultry. In this important case, he ruled that a New Deal law on working conditions did not apply to a New York poultry firm that conducted its business only within the state.[190] Hand wrote in his opinion: "It is always a serious thing to declare any act of Congress unconstitutional, and especially in a case where it is part of a comprehensive plan for the rehabilitation of the nation as a whole. With the wisdom of that plan we have nothing whatever to do ..."[190] Hand also occasionally went against the government in the area of free speech. He believed that courts should protect the right to free speech even against the majority will. In Hand's view, judges must remain detached at times when public opinion is hostile to minorities and governments issue laws to repress those minorities.[191] Hand was the first judge to rule on a case arising from the Espionage Act of 1917, which sought to silence opposition to the war effort. In his decision on Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten, he defined his position on political incitement:

Detestation of existing policies is easily transformed into forcible resistance of the authority which puts them in execution, and it would be folly to disregard the causal relation between the two. Yet to assimilate agitation, legitimate as such, with direct incitement to violent resistance, is to disregard the tolerance of all methods of political agitation which in normal times is a safeguard for free government. The distinction is not scholastic subterfuge, but a hard-bought acquisition in the fight for freedom.[192]

In the case of United States v. Dennis in 1950, Hand made a ruling that appeared to contradict his Masses decision. By then, a series of precedents had intervened, often based on Oliver Wendell Holmes's "clear and present danger" test, leaving him less room for maneuver.[193] Hand felt he had "no choice" but to agree that threats against the government by a group of Communists were illegal under the repressive Smith Act of 1940.[194] In order to do so, he interpreted the "clear and present danger" in a new way. "In each case," he wrote, "[courts] must ask whether the gravity of the 'evil', discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger." This formula allowed more scope for curbing free speech in cases where, as the government believed with Communism, the danger was grave, whether it was immediate or not.[195] Critics and disappointed liberals accused Hand of placing his concern for judicial restraint ahead of freedom of speech.[196] Hand confided to a friend that, if it had been up to him, he would "never have prosecuted those birds".[197]

In the opinion of Kathryn Griffith, "The importance of Learned Hand's philosophy in terms of practical application to the courts lies generally in his view of the pragmatic origin of all law, but most specifically in his unique interpretation of the Bill of Rights."[198] Hand proposed that the Bill of Rights was not law at all but a set of "admonitory" principles to ensure the fair exercise of constitutional powers.[199] He therefore opposed the use of its "due process of law" clauses as a pretext for national intervention in state legislation. He even advocated the removal of those clauses from the Constitution. In Hand's analysis, "due process" is no more than a stock phrase to cover a long tradition of common law procedure.[200] He contended that the term had inflated in scope beyond the meaning intended in the Bill of Rights. The result was the misuse of due process to invade rights that the Constitution was designed to protect. For Hand, a law passed by an elected body should be presumed to meet the test of due process. A court that decides otherwise and strikes down such a law is acting undemocratically.[201] Hand maintained this stance even when the Supreme Court struck down anti-liberal laws that he detested.[202] His reasoning has never been widely accepted. Critics of his position included his colleague on the Second Circuit, Jerome Frank, who wrote: "[I]t seems to me that here, most uncharacteristically, Judge Hand indulges in a judgement far too sweeping, one which rests on a too-sharp either-or, all or nothing, dichotomy. ... Obviously the courts cannot do the whole job. But just as obviously, they can sometimes help to arrest evil popular trends at their inception."[203]

Richard Posner, an influential appellate judge reviewing a biography of Hand, asserts that Hand "displayed a positive antipathy toward constitutional law. To exaggerate only a little, he didn't think judges should have anything to do with it."[204] Posner suggests that although Hand is remembered today as one of the three greatest judges in American history, his status as a truly "great judge" was not based on his "slight" contributions to First Amendment jurisprudence or other fields of constitutional law, but rather on his decisions in other areas such as antitrust, intellectual property, and tort law.[204]

Influence edit

Hand authored approximately 4,000 judicial opinions during his career. Admired for their clarity and analytic precision, they have been quoted more often in Supreme Court opinions and by legal scholars than those of any other lower-court judge.[3] Both Hand's dissent in United States v. Kennerley[60] and his ruling in United States v. Levine[205] have often been cited in obscenity cases.[206] Hand's view that literary works should be judged as a whole and in relation to their intended readership is now accepted in American law. His use of historical data to gauge legislative intent has become a widespread practice. According to Archibald Cox: "The opinions of Judge Hand have had significant influence both in breaking down the restrictions imposed by the dry literalism of conservative tradition and in showing how to use with sympathetic understanding the information afforded by the legislative and administrative processes."[207] Hand's decision in the 1917 Masses case influenced Zechariah Chafee's widely read book, Freedom of Speech (1920). In his dedication, Chafee wrote, "[Hand] during the turmoil of war courageously maintained the traditions of English-speaking freedom and gave it new clearness and strength for the wiser years to come."[208]

Learned Hand played a key role in the interpretation of new federal crime laws in the period following the passing of the U.S. Criminal Code in 1909.[209] In a series of judicial opinions and speeches, he opposed excessive concern for criminal defendants, and wrote "Our dangers do not lie in too little tenderness to the accused. Our procedure has always been haunted by the ghost of the innocent man convicted. ... What we need to fear is the archaic formalism and watery sentiment that obstructs, delays and defeats the prosecution of crime." He insisted that harmless trial errors should not automatically lead to a reversal on appeal. Hand balanced these views with important decisions to protect a defendant's constitutional rights concerning unreasonable searches, forced confessions and cumulative sentences.[210]

His opinions have also proved lasting in fields of commercial law. Law students studying torts often encounter Hand's 1947 decision for United States v. Carroll Towing Co.,[211] which gave a formula for determining liability in cases of negligence.[212] Hand's interpretations of complex Internal Revenue Codes, which he called "a thicket of verbiage", have been used as guides in the gray area between individual and corporate taxes.[213] In an opinion sometimes seen as condoning tax avoidance, Hand stated in 1947 that "there is nothing sinister in so arranging one's affairs as to keep taxes as low as possible".[214] He was referring to reporting of individual income through corporate tax forms for legitimate business reasons. In tax decisions, as in all statutory cases, Hand studied the intent of the original legislation. His opinions became a valuable guide to tax administrators.[215] Hand's landmark decision in United States v. Aluminum Company of America in 1945 influenced the development of antitrust law.[216] His decisions in patent, copyright, and admiralty cases have contributed to the development of law in those fields.[217]

Hand was also a founding member of the American Law Institute, where he helped develop the influential Restatements of the Law serving as models for refining and improving state codes in various fields.[218] One American Law Institute recommendation was to decriminalize sexual conduct such as adultery and homosexuality, for which reason the July–August 1955 issue of the Mattachine Society Review, the magazine of the country's first nationwide homosexual organization, published a salute to Judge Hand featuring his photograph on the cover.[219]

After Hand's lectures and publications became widely known, his influence reached courts throughout the country.[220] On the occasion of his 75th birthday on January 27, 1947, The Washington Post reported: "He has won recognition as a judges' judge. His opinions command respect wherever our law extends, not because of his standing in the judicial hierarchy, but because of the clarity of thought and the cogency of reasoning that shape them."[221]

To the wider public, who knew little of his legal work, Hand was by then a folk hero.[222] Social scientist Marvin Schick has pointed out that this mythic status is a paradox.[223] Because Hand never served on the Supreme Court, the majority of his cases were routine and his judgments rooted in precedent. On Hand's retirement in 1951, Felix Frankfurter predicted that his "actual decisions will be all deader than the Dodo before long, as at least many of them are already".[224] Working for a lower court, however, saved Hand from the taint of political influence that often hung over the Supreme Court. Hand's eloquence as a writer played a larger part in the spread of his influence than the substance of his decisions; and Schick believes that the Hand myth brushes over contradictions in his legal philosophy. Hand's reputation as a libertarian obscures the fact that he was cautious as a judge. Though a liberal, he argued for judicial restraint in interpreting the Constitution, and regarded the advancement of civil liberties as a task for the legislature, not the courts. In his 1958 Holmes Lectures, for example, he voiced doubts about the constitutionality of the Warren Court's civil rights rulings.[225] This philosophy of judicial restraint failed to influence the decisions of the Supreme Court during Hand's lifetime and afterwards.

Finally, in an essay called Origin of a Hero discussing his novel the Rector of Justin, author Louis Auchincloss says the main character was not based on a headmaster—certainly not, as was often speculated, Groton's famous Endicott Peabody. "If you want to disguise a real life character," Auchincloss advised fellow novelists, "just change his profession." His actual model for the Rector of Justin was "the greatest man it has been my good luck to know"—Judge Learned Hand.[226]

Selected works edit

- Hand, Learned (1941), Liberty, Stamford, Connecticut: Overbrook, OCLC 2413475.

- Hand, Learned (1952), Dilliard, Irving (ed.), The Spirit of Liberty: Papers and Addresses of Learned Hand, New York: Knopf, OCLC 513793.

- Hand, Learned (1958), The Bill of Rights, Oliver Wendell Holmes Lectures, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, OCLC 418364.

- Hand, Learned (1968), Shanks, Hershel (ed.), The Art and Craft of Judging: The Decisions of Judge Learned Hand, New York: Macmillan, OCLC 436539.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Schick 1970, pp. 188–89

- ^ Dworkin 1996, p. 342. Quoted from Hand's 1958 Holmes Lectures.

- ^ a b Stone 2004, p. 200; Vile 2003, p. 319

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 3–5

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 3, 7, 40; Griffith 1973, p. 3.

- ^ Charles E. Wyzanski, quoted in Schick 1970, p. 13

- ^ a b Schick 1970, p. 13

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 7

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 6

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 3

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 6–9

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 10–11

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 4, 6, 11

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 22

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 4

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 4–5

- ^ Vile 2003, p. 320

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 20, 23–25

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 3–4

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 20–22

- ^ Two were subsequently released commercially as part of a disc of American folksongs. See "Judge Learned Hand Turns Singer in New U.S. Album of Folk Music", The New York Times, pp. 1, 15, May 11, 1953 Excerpts can be heard as part of Wade, Stephen (October 5, 1999), "Learned Hand", All Things Considered, NPR, archived from the original on January 25, 2022, retrieved July 27, 2008 In 2013, The Green Bag released "Songs of His Youth", a vinyl disc of several of the songs, along with some of Hand's in-studio commentary. Davies, Ross (2013), Learned Hand Sings, Part One: Liner Notes for 'Songs of His Youth', doi:10.2139/ssrn.2271070, SSRN 2271070

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 26

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 32–33

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 26–30, 76

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b Griffith 1973, p. 4

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 32

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 40–43

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 46–47

- ^ a b Dworkin 1996, p. 333

- ^ Carrington 1999, p. 206

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 47–50

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 50–52; Griffith 1973, p. 4

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 53–55

- ^ Carrington 1999, p. 137; Schick 1970, p. 14; Griffith 1973, pp. 4–5

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 56–59

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 59–61

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 61–63

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 64–65. This switch did not prove permanent: over the course of the years, Hand voted equally for Democratic and Republican candidates.

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 68–70

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 72

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 78

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 79

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 80–81

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 172–174

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 7

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 171–73

- ^ Gilbert, Alma, Maxfield Parrish: The Masterworks, Third Edition (Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press, 2001) p. 110.

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 183–187

- ^ a b Gunther 1994, pp. 187–188

- ^ Stettner 1993, p. 25

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 190–193

- ^ Stettner 1993, p. 76

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 195, 198–202

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 101–105

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 107

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 123–124, 128–133; Schick 1970, p. 14; Griffith 1973, p. 5

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 135–136

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 137–138, 144–145

- ^ a b United States v. Kennerley, 209 Fed. 119 (S.D.N.Y. 1913)

- ^ Boyer 2002, pp. 46–48

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 154; Rabban 1999, p. 146; Regina v. Hicklin, LR 3 QB 360 (1868).

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 149–150

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 202

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 202–204; Schick 1970, p. 14

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 206–210, 221–24

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 212–225

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 227–229

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 232

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 229–232

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 233. The new party structure incorporated Jane Addams' Progressive Service, an educational organization aimed at spreading the reformist agenda to the public and to the legislators.

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 5

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 14

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 233–236

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 237

- ^ Stone 2004, p. 166

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 239–241

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 190, 241–244

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 190, 250–251

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 251–256

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 176; Shanks 1968, pp. 84–97; Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten, 244 Fed. 535 (S.D.N.Y. 1917)

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 151, 157; Stone 2004, pp. 157, 164–165

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 151–152

- ^ Schick 1970, pp. 177–178; Rabban 1999, p. 296; Stone 2004, p. 177

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 152, 156–160; Stone 2004, pp. 165–170

- ^ Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

- ^ Irons 1999, pp. 270, 275, 279–280; Gunther 1994, pp. 161–167; Stone 2004, pp. 198–207

- ^ "Judge Hand's injunction against the postmaster's exclusion of The Masses from the mails, though reversed on appeal, is seen, in retrospect, as the precursor of the federal court's present protection of freedom of the press." Judge Charles E. Wyzanski. Qtd. in Griffith 1973, p. 6

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 151–152, 170

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 155; Stone 2004, pp. 165–166

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 161, 257–260, 270–71

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 263–266

- ^ White 2007, p. 214; Schick 1970, p. 17

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 270–277; Schick 1970, p. 15. Taft had once dismissed Hand as "a wild Roosevelt man and a Progressive".

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 281

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 344–352

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 362–368

- ^ a b c d Schick 1970, p. 16

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 418–428

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 416, 435–438

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 457–460; Carrington 1999, p. 141

- ^ United States v. A. L. A. Schechter, 76 F.2d 617 (2d Cir. 1935)

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 446–448, 451

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 471; Schick 1970, p. 163

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 472

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 485

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 5

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 503–509

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 514–516, 521; Schick 1970, p. 5

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 9–10

- ^ Ashworth, Kenneth (2001). Caught between the dog and the fireplug, or how to survive public service. Washington, Dc: Georgetown University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 0-87840-847-9.

Douglas, qtd in Ashworth.

- ^ Vile 2003, p. 324

- ^ Letter from Learned Hand to Felix Frankfurter (Feb. 6, 1944) (available in Felix Frankfurter Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.). Quoted in Melvin I. Urofsky, William O. Douglas As a Common Law Judge Archived 2017-05-10 at the Wayback Machine, 41 Duke Law Journal 133, 135 n.18 (1991).

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 566–570; Dworkin 1996, p. 335

- ^ Margolick, David (April 22, 1994). "At the Bar; After two decades' labor, a chronicle on the life of perhaps the finest judge ever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 535–541

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 541–543. Lovett was removed from his government job by an Act of Congress, but in 1946 the Supreme Court ruled his dismissal unconstitutional as a bill of attainder.

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 543–547

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 11–12

- ^ Qtd. in Gunther 1994, p. 549

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 11–13

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 549–552

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 575

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 576–577

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 578; Stone 2004, p. 398

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 581

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 585; Stone 2004, p. 399

- ^ United States v. Coplon, 185 F.2d 629 (2d Cir. 1950); Dennis v. United States, 183 F.2d. 201 (2d Cir. 1950); United States v. Remington, 208 F.2d. 567 (2d Cir. 1950)

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 592–597

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 596; Griffith 1973, p. 37

- ^ Schick 1970, pp. 176–181; Griffith 1973, pp. 150–152; Irons 1999, pp. 379–380

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 598–599

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 624–625; Stone 2004, p. 369

- ^ Hand 1977, pp. 223–24

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 588–589

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 589–590

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 586–587, 639

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 15

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 639–643

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 570–571

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 84–85

- ^ Dworkin 1996, p. 347

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 620

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 300–302

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 586

- ^ Lochner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45 (1905)

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 654–657; Carrington 1999, pp. 141–143

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 662–664; Carrington 1999, pp. 141–143; Griffith 1973, p. 109

- ^ Vanessa Grigoriadis (January 29, 2010). "Searching for J.D. Salinger: A Writer's New Hampshire Quest". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ Slawenski, Kenneth (2010). J. D. Salinger: A Life. Random House. pp. 281–282. ISBN 9781611299052. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 674

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 676

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 677

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 679

- ^ Grondahl, Paul (December 5, 2013). "Learned Hand (1872-1961): Judicial eminence, '10th man on the U.S. Supreme Court'". Albany Times-Union. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "Skepticism is my only gospel, but I don't want to make a dogma out of it." Qtd. in Lewis F. Powell, "Foreword", Gunther 1994, p. x

- ^ a b Griffith 1973, p. vii

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 405

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 165; Dworkin 1996, p. 12

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 192; Dworkin 1996, p. 342

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 131–140; White 2007, pp. 217–218

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 186

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 57–58; Dworkin 1996, pp. 342–343

- ^ "The limits Hand placed on choice are similar to those John Stuart Mill placed upon freedom when he denied the freedom to destroy liberty or the social and political structure which protected it." Griffith 1973, p. 60

- ^ Carrington 1999, p. 138; Polenberg 1995, pp. 296–301

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 62–63

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 193–194

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 65

- ^ Wyzanski 1964, p. vi

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 86. "Hamilton thought government consisted of combinations based on self-interest and that liberty did not rest on anarchy. Man required an ordered society, which included not only individual concerns but collective interests and which permitted human life to rise above that of the savage and made possible joint efforts and thus more comfort, security, and leisure for a better life. He believed that while Jacobins cried for liberty what they really wanted was to exercise their own tyranny over the mob. It appeared to Hand that history had proved Hamilton right."

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 193

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 67

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 190

- ^ a b Griffith 1973, pp. 56–57, 60–63

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 453

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 368, 535

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 191

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 83

- ^ Dworkin 1996, p. 412

- ^ Wyzanski 1964, p. viii

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 118–123

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 18–19

- ^ Horwitz 1995, p. 264; Schick 1970, pp. 162–163; Gunther 1994, p. 122

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 109, 211

- ^ Carrington 1999, p. 141

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 219–222

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 164

- ^ White 2007, p. 235

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 112

- ^ a b Griffith 1973, pp. 112–113

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 107–108

- ^ Qtd. in Griffith 1973, p. 144

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 604–605; Stone 2004, pp. 399–400

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 146–153

- ^ Irons 1999, p. 380; Schick 1970, pp. 180–181; Stone 2004, p. 400

- ^ Dworkin 1996, pp. 338–39

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 603

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 192–193

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 130–138; Horwitz 1995, pp. 262–263

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 122

- ^ "The statute may be far from the best solution of the conflict with which it deals; but if it is the result of an honest effort to embody that compromise or adjustment that will secure the widest acceptance and most avoid resentment it is 'Due Process of Law' and conforms to the First Amendment." From Hand's The Bill of Rights. Qtd. in Schick 1970, p. 163

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 383; Carrington 1999, p. 140

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 140

- ^ a b Posner & Gunther 1994, pp. 511, 514

- ^ United States v. Levine, 83 F.2d 156 (2d Cir. 1936); see also United States v. One Book Called Ulysses, 72 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1934), in which a trial court decision by Judge John M. Woolsey was affirmed by a Second Circuit panel including Hand.

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 157; Gunther 1994, p. 149

- ^ Qtd. in Griffith 1973, p. 174

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 178

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 35

- ^ Gunther 1994, pp. 304–305, 532–533; Judd 1947, pp. 405–422

- ^ United States v. Carroll Towing Co., 159 F.2d 169 (2nd Cir. 1947)

- ^ Weinrib 1995, p. 48. Hand proposed that the defendant's duty is a function of three variables: the probability of an accident's occurring, the gravity of loss if it should occur, and burden of adequate precautions. He expressed this in the algebraic formula: "If the probability be called P; the injury, L; and the burden, B; liability depends on whether B is less than L multiplied by P: i.e., where B is less than PL." See also Calculus of negligence.

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 169

- ^ Griffith 1973, p. 26

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 26–30. See also Chirelstein 1968, "Learned Hand's Contribution to the Law of Tax Avoidance".

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 32–34; Schick 1970, pp. 170–171, 188; United States v. Aluminium Company of America, 148 F.2d 416 (2nd Cir. 1945). In this case, the Second Circuit took the place of the Supreme Court under a special statute, enacted after the Supreme Court lacked quorum in the case because of recusals. Hand's opinion set the standard for future rulings.

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 188

- ^ Griffith 1973, pp. 43–44; Gunther 1994, pp. 410–414

- ^ Mattachine Review, Issue No. 4, July–August 1955, cover and p. 2.

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 189

- ^ Qtd. in Gunther 1994, p. 574

- ^ Gunther 1994, p. 550

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 12

- ^ Schick 1970, pp. 154, 187

- ^ Schick 1970, p. 355; Auerbach 1977, p. 259

- ^ Origin of a Hero, in Auchincloss, Louis (1979), Life, Law, and Letters: Essays and Sketches, Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-28151-2

Bibliography edit

- Auerbach, Jerold S. (1977), Unequal Justice: Lawyers and Social Change in Modern America, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-502170-7.

- Boudin, Michael; Gunther, Gerald (January 1995), "The Master Craftsman", Stanford Law Review, 47 (2): 363–386, doi:10.2307/1229231, JSTOR 1229231. (JSTOR subscription required for online access.)

- Boyer, Paul S. (2002), Purity in Print: Book Censorship in America from the Gilded Age to the Computer Age (2nd ed.), Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 978-0-299-17584-9

- Carrington, Paul (1999), Stewards of Democracy: Law as Public Profession, New York: Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-8133-6832-0.