Charles Henry Pywell Daniell (5 March 1894 – 31 October 1963)[1] was an English actor who had a long career in the United States on stage and in cinema. He came to prominence for his portrayal of villainous roles in films such as Camille (1936), The Great Dictator (1940), Holiday (1938) and The Sea Hawk (1940). Daniell was given few opportunities to play sympathetic or 'good guy' roles; an exception was his portrayal of Franz Liszt in the biographical film of Robert and Clara Schumann, Song of Love (1947). His name is sometimes spelled "Daniel".[2]

Henry Daniell | |

|---|---|

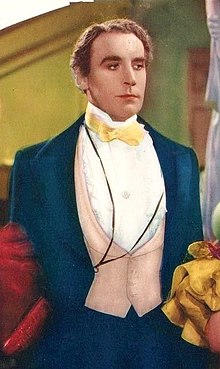

Daniell in Camille (1936) | |

| Born | Charles Henry Pywell Daniell 5 March 1894 |

| Died | 31 October 1963 (aged 69) Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Memorial Cemetery, Santa Monica |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1913–1963 |

| Spouse |

Ann Knox

(m. 1932) |

| Children | 1 |

Biography edit

Early life edit

Daniell was born in Barnes, then lived in Surrey, and was educated at St Paul's School in London and at Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk.

English stage edit

He made his first appearance on the stage in the provinces in 1913, and on the London stage at the Globe Theatre on 10 March 1914, in a walk on role in the revival of Edward Knoblock's Kismet.[3] He followed it with Monna Vanna and The Sphinx.[4]

In 1914, he joined the 2nd Battalion of the Norfolk Regiment during World War I, but was invalided out the following year after being severely wounded in combat. Thereafter, he appeared at the New Theatre in October 1915 as Police Officer Clancy in Stop Thief! and, from May 1916, at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket.[4]

Broadway and early films edit

In April 1921, Daniell appeared at the Empire Theatre in New York City, as Prince Charles of Vaucluse in Clair de Lune, and subsequently toured for the next three years, reappearing in London at the Garrick Theatre in August 1925 as Jack Race in Cobra.

Daniell returned to Broadway in The Woman on the Jury (1923) and The Second Mrs. Tanqueray (1924).

He again went to New York for the first six months of 1929, appearing at the Morosco Theatre in January as Lord Ivor Cream in Serena Blandish, returning in July to London where he played John Carlton in Secrets at the Comedy Theatre.

He again toured America in 1930–31, this time appearing on the Pacific Coast at Los Angeles as well as New York once more. He returned to London for another packed programme of stage performances, which he continued in Britain and the United States while also beginning his film career in 1929 with The Awful Truth, with leading lady Ina Claire.[2]

He was also in Jealousy (1929) with Jeanne Eagels in her last role.[5][3] He was in The Last of the Lone Wolf (1930) and returned to Broadway for Heat Wave (1931) and For Services Rendered (1933). He appeared in the West End in Walter C. Hackett's Afterwards in 1933.

Daniell returned to films in the British The Path of Glory (1934) then was back on Broadway in Kind Lady (1935).[6]

On Broadway he was in Murder Without Crime (1943) and Lovers and Friends (1943-44) with Katherine Cornell. On Broadway, Daniell was in revivals of The Winter's Tale (1946), Lady Windermere's Fan (1946-47), and The First Mrs. Fraser (1947).[7][8]

Film career, 1936–1950 edit

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cast him in The Unguarded Hour (1936), Camille (1936) with Greta Garbo (as the Baron de Varville), Under Cover of Night (1936), The Thirteenth Chair (1937), The Firefly (1937), and Madame X (1937).

Columbia borrowed him for a role in Holiday (1938), returning to MGM for Marie Antoinette (1938), playing Nicholas de la Motte. He appeared in Yankee Fable on Broadway.[9]

At Warner Bros., Daniell appeared in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) as Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, with Bette Davis and Errol Flynn in the leads directed by Michael Curtiz.

He followed it with We Are Not Alone (1939), All This, and Heaven Too (1940), and The Sea Hawk (1940). In the latter, directed by Curtiz, he played the treacherous Lord Wolfingham (no relation to Francis Walsingham), fighting Errol Flynn in what has been considered one of the most spectacular sword fighting duels ever filmed.[10] When Michael Curtiz cast him in this film, Daniell initially refused the role because he could not fence. Curtiz accomplished the climactic duel through the use of shadows and over-shoulder shots, with a double fencing Flynn with ingenious inter-cutting of their faces.

Charlie Chaplin borrowed him for a part in The Great Dictator (1940) (playing Garbitsch, to sound like "garbage", a parody of Joseph Goebbels), then he returned to MGM for The Philadelphia Story (1940), and A Woman's Face (1940).[4]

At Warner, Daniell had a role in a B movie, Dressed to Kill (1941). He did The Feminine Touch (1941) at MGM, Four Jacks and a Jill (1942) at RKO and Castle in the Desert (1942) at Fox.

Daniell appeared in the Basil Rathbone-Nigel Bruce Sherlock Holmes film Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1943) at Universal. For the studio, he was also cast in Nightmare (1942), and The Great Impersonation (1942).

Back at MGM, he was in Reunion in France (1942) then he returned to Universal for another Sherlock Holmes film, Sherlock Holmes in Washington (1943). At Warner Bros., he was in Mission to Moscow (1943) playing Minister von Ribbentrop. He returned to Broadway for a revival of Hedda Gabler (1942).

He appeared in Watch on the Rhine (1943), Jane Eyre (1943), and The Suspect (1944), as Charles Laughton's blackmailing next-door neighbour.

Daniell had a lead role in The Body Snatcher (1945), with Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, followed by Hotel Berlin (1945) and a third Sherlock Holmes film, The Woman in Green (1945), this time as Holmes arch-nemesis Professor Moriarty.

Daniell was King William III in Captain Kidd (1945). He had the lead in a TV version of Angel Street (1946) then was William of Pembroke in The Bandit of Sherwood Forest (1946) at Columbia.

Daniell appeared as composer Franz Liszt in Song of Love (1947) starring Katharine Hepburn. He was villainous in The Exile (1947), Wake of the Red Witch (1948), and Siren of Atlantis (1949). On Broadway, he appeared in That Lady (1950).[11]

Television edit

Daniell appeared in more swashbucklers, The Secret of St. Ives (1949) and Buccaneer's Girl (1950), and begin appearing on television shows such as Repertory Theatre, Studio One in Hollywood, Armstrong Circle Theatre, and Lights Out. He continued to appear on stage in The Cocktail Party (1951), Remains to Be Seen (1952) and My Three Angels (1953-54).[12]

Daniell was also in Studio 57, Schlitz Playhouse, Matinee Theatre, Kraft Theatre, Alcoa Theatre, Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, Playhouse 90, The Californians, Lux Playhouse, Maverick, Riverboat, and Startime (an adaptation of My Three Angels). He continued to be in demand for features such as The Sun Also Rises (1957), Les Girls (1957), The Story of Mankind (1957) (AS Pierre Cauchon), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), and the cult horror classic, The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake (1959).

Daniell had more TV roles in Markham, The Swamp Fox, Wagon Train, Peter Gunn, Shirley Temple's Storybook, The Islanders, The Law and Mr. Jones and several episodes of Boris Karloff's TV series Thriller.

His final TV appearances were in episodes of Combat! and 77 Sunset Strip and he was on Broadway in Lord Pengo (1962-63) with Charles Boyer.

Later films edit

Daniell appeared in some big screen epics such as The Egyptian (1954) (directed by Curtiz), The Prodigal (1955) and Diane (1956), but was increasingly in television: Lux Video Theatre, Jane Wyman Presents The Fireside Theatre, TV Reader's Digest, Producers' Showcase (an adaptation of The Barretts of Wimpole Street), and Telephone Time.

He had a rare contemporary part in The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956) and was in Lust for Life (1956). In 1957, he played the instructing solicitor to Charles Laughton's leading counsel barrister in Witness for the Prosecution (1957).

Daniell claimed one of his favourite roles was as Tony Curtis's supervisor in the Blake Edwards film Mister Cory (1957) at a time when his career was clearly slowing down, but he spoke some of the best and most memorable lines in the movie, "A gentleman never grabs. Manners, Mister Cory. I find them a prerequisite in any circumstance." He could also be seen in the films Madison Avenue (1961), Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961), The Comancheros (1961), The Notorious Landlady (1962), Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962), The Chapman Report (1962) and Mutiny on the Bounty (1962).

His last role was a small uncredited appearance as the British Ambassador in the 1964 film My Fair Lady directed by his old friend George Cukor. He appears in the embassy ball scene. He is seen as Eliza arrives and when introduced to her shakes her hand and says "Miss Doolittle". Later, Daniell presents Eliza to the Queen of Transylvania with the one line, "Miss Doolittle, ma'am." In the commentary on the DVD, at the moment he appears on-screen in the role, it is mentioned that the day he shot the scene was "his last day on earth", as he died from a heart attack that very evening either (reports differ) at his home, or on the set of My Fair Lady on 31 October 1963.[13]

Personal life edit

Daniell married Ann Knox and, in the years following World War II, lived in Los Angeles, California. They had one child.

Author P. G. Wodehouse reported that Danniell and his wife were known to witness, and perhaps participate in, orgies in Los Angeles, remarking: "there's something rather pleasantly domestic about a husband and wife sitting side by side with their eyes glued to peepholes."[14]

Death edit

An obituary distributed by United Press International and datelined Hollywood reported, "Daniell was stricken yesterday from Halloween day at his home in nearby Santa Monica a few hours before he was due to report on the set of the film version of My Fair Lady at Warner Bros. studio."[5] He died of a myocardial infarction.[15]

Filmography edit

- The Awful Truth (1929) as Norman Warriner (film debut)

- Jealousy (1929) as Clement

- The Path of Glory (1934) as King Maximillian

- The Unguarded Hour (1936) as Hugh Lewis

- Camille (1936) as Baron de Varville

- Under Cover of Night (1937) as Marvin Griswald

- The Thirteenth Chair (1937) as John Wales

- The Firefly (1937) as General Savary

- Madame X (1937) as Lerocle

- Holiday (1938) as Seton Cram

- Marie Antoinette (1938) as La Motte

- The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) as Sir Robert Cecil

- We Are Not Alone (1939) as Sir Ronald Dawson

- The Sea Hawk (1940) as Lord Wolfingham

- All This, and Heaven Too (1940) as Broussais

- The Great Dictator (1940) as Garbitsch

- The Philadelphia Story (1940) as Sidney Kidd

- A Woman's Face (1941) as Public Prosecutor

- Dressed to Kill (1941) as Julian Davis

- The Feminine Touch (1941) as Shelley Mason

- Four Jacks and a Jill (1942) as Bobo

- Castle in the Desert (1942) as Watson King

- The Voice of Terror (1942) as Anthony Lloyd

- Nightmare (1942) as Capt. Stafford

- The Great Impersonation (1942) as Frederick Seamon

- Reunion in France (1942) as Emile Fleuron

- Sherlock Holmes in Washington (1943) as William Easter

- Mission to Moscow (1943) as Minister von Ribbentrop

- Watch on the Rhine (1943) as Phili Von Ramme

- Jane Eyre (1943) as Henry Brocklehurst

- The Suspect (1944) as Mr. Simmons

- The Body Snatcher (1945) as Dr. Wolfe 'Toddy' MacFarlane

- Hotel Berlin (1945) as Baron Von Stetten

- The Woman in Green (1945) as Moriarty

- Captain Kidd (1945) as King William III

- The Bandit of Sherwood Forest (1946) as The Regent - William of Pembroke

- Song of Love (1947) as Franz Liszt

- The Exile (1947) as Colonel Ingram

- Wake of the Red Witch (1948) as Jacques Desaix

- Siren of Atlantis (1949) as Blades

- The Secret of St. Ives (1949) as Maj. Edward Chevenish

- Buccaneer's Girl (1950) as Capt. Duval

- The Egyptian (1954) as Mekere

- The Prodigal (1955) as Ramadi

- Diane (1956) as Gondi

- The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956) as Bill Ogden

- Lust for Life (1956) as Theodorus Van Gogh

- Mister Cory (1957) as Mr. Earnshaw

- The Sun Also Rises (1957) as Doctor

- Les Girls (1957) as Judge

- The Story of Mankind (1957) as Bishop Cauchon

- Witness for the Prosecution (1957) as Mayhew

- From the Earth to the Moon (1958) as Morgana

- Maverick (1959, TV) as Rene St. Cloud

- The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake (1959) as Dr. Emil Zurich

- The Magical World of Disney (1960, TV) as Colonel Townes

- Wagon Train (1960, TV) as Mr. Morton W. Snipple/Sir Alexander Drew

- Shirley Temple's Storybook (1960, TV) as Sir Oliver

- Madison Avenue (1961) as Stipe

- The Law and Mr. Jones (1961, TV) as Isaac Beckett

- Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1961) as Dr. Zucco

- Thriller (1960-1961, TV) as Various Roles

- The Comancheros (1961) as Gireaux

- The Notorious Landlady (1962) as Stranger

- Five Weeks in a Balloon (1962) as Sheik Ageiba

- The Chapman Report (1962) as Dr. Jonas

- Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) as Court-martial judge (uncredited)

- My Fair Lady (1964) as Ambassador (final film, uncredited)

References edit

- Who's Who in the Theatre, edited by John Parker, tenth edition, revised, London, 1947, pp. 477–478

Notes edit

- ^ Castronova, Frank V., ed. (1998). Almanac of Famous People. Detroit: Gale. p. 431. ISBN 0-7876-0045-8.

- ^ a b "Henry Daniell Playbill". Playbill. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ a b Henry Daniell, British Actor, Dies at Home Los Angeles Times 1 November 1963: F7.

- ^ a b c HENRY DANIELL LONG FAMED FOR CHARACTER ROLES Los Angeles Times 14 November 1940: B4.

- ^ a b "Character Actor Henry Daniell Dies Suddenly". The Fresno Bee The Republican. California, Fresno. United Press International. 1 November 1963. p. 30.

- ^ THE THEATRE: Macabre Excellence Wall Street Journal 26 April 1935: 13.

- ^ OSCAR WILDE PLAY IN REVIVAL TONIGHT: 'Lady Windermere's Fan' to Star Cornelia Skinner and Henry Daniell at Cort Dowling, Singer Dissolve Firm "Gypsy Lady" to Lose Two By SAM ZOLOTOW. The New York Times 14 October 1946: 38.

- ^ HENRY DANIELL, ACTOR, 69, DEAD: Played Suave Villain Role in Stage and Screen Plays Had wide Range Marcus Blechman, 1948. The New York Times (11 Nov 1963: 31.

- ^ News and Gossip of Fall Amusements, With Index of What to See and Where to Go: Henry Daniell Joins Cast of New Comedy In 'Yankee Fable' Supports Ina Claire Plays Gen. Howe The Washington Post 30 October 1938: TS4.

- ^ "The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies.

- ^ MISS CORNELL BACK TONIGHT IN DRAMA: Portrays One-Eyed Princess in 'That Lady,' Which Is Due at Martin Beck Theatre By LOUIS CALTA. The New York Times 22 November 1949: 37.

- ^ Henry Daniell Featured In Melodrama at Plymouth By Edwin F. Melvin. The Christian Science Monitor 28 October 1952: 7.

- ^ Miller, Frank. "Trivia and Fun Facts About My Fair Lady". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies, Inc. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (1993). For the Sake of Argument Essays and Minority Reports. London: Verso. p. 314. ISBN 9780860914358. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "HENRY DANIELL, ACTOR, 69, DEAD; Played Suave Villain Role in Stage and Screen Plays Had wide Range". The New York Times. 1 November 1963.