Coal phase-out is an environmental policy intended to stop burning coal in coal-fired power plants and elsewhere, and is part of fossil fuel phase-out. Coal is the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, therefore phasing it out is critical to limiting climate change as laid out in the Paris Agreement.[4][5] The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that coal is responsible for over 30% of the global average temperature increase above pre-industrial levels.[6] Some countries in the Powering Past Coal Alliance have already stopped.[7]

China and India burn a lot of coal.[8] But the only significant funding for new plants is for coal power in China.[9] The health and environmental benefits of coal phase-out, such as limiting biodiversity loss and respiratory diseases, are greater than the cost.[10] Developed countries may part finance the phase out for developing countries through the Just Energy Transition Partnership, provided they do not build any more coal plants.[11] One major intergovernmental organisation (the G7) committed in 2021 to end support for coal-fired power stations within the year.[12] It has been estimated that coal phase-out could benefit society by over 1% of GDP each year to the end of the 21st century,[13] so economists have suggested a Coasean bargain in which already developed countries help finance the coal phase-out of still developing countries.[14]

In order to meet global climate goals and provide power to those that do not currently have it coal power must be reduced from nearly 10,000 TWh to less than 2,000 TWh by 2040.[15] Phasing out coal has short-term health and environmental benefits which exceed the costs,[16] but some countries still favor coal,[17] and there is much disagreement about how quickly it should be phased out.[18][19] However many countries, such as the Powering Past Coal Alliance, have already or are transitioned away from coal;[20] the largest transition announced so far being Germany, which is due to shut down its last coal-fired power station between 2035 and 2038.[21] Germany is using reverse auctions to compensate coal-fired power plants for shutting down ahead of schedule.[22] Some countries use the ideas of a "just transition", to provide with some of the benefits of transition early pensions for coal miners.[23] However, low-lying Pacific Islands are concerned the transition is not fast enough and that they will be inundated by sea level rise, so they have called for OECD countries to completely phase out coal by 2030 and other countries by 2040.[24] In 2020, although China built some plants, globally more coal power was retired than built: the Secretary-General of the United Nations has also said that OECD countries should stop generating electricity from coal by 2030 and the rest of the world by 2040.[25] Phasing down coal was agreed at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in the Glasgow Climate Pact. Vietnam is among few coal-dependent developing countries that pledged to phase out unabated coal power by the 2040s or as early as possible thereafter[26]

In 2022–2023, coal's use had risen. The IEA points out that high gas prices due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and extreme weather events as contributors to the increase.[27][28]

In April 2024, the G7 countries agreed to close all coal power plants in 2030–2035 unless their greenhouse gases are captured or the countries find another way to align their emissions with the 1.5 degree goal.[29][30]

Peak coal

editPeak coal is the peak consumption or production of coal by a human community. Peak coal can be driven by peak demand or peak supply. Historically, it was widely believed that the supply-side would eventually drive peak coal due to the depletion of coal reserves. However, since the increasing global efforts to limit climate change, peak coal has been driven by demand.[31] This is due in large part to the rapid expansion of natural gas and renewable energy.[31] As of 2024 over 40% of all energy sector CO2 emissions are from coal, and many countries have pledged to phase-out coal.[32]

The peak of coal's share in the global energy mix was in 2008, when coal accounted for 30% of global energy production.[31] Coal consumption is declining in the United States and Europe, as well as developed economies in Asia.[31] However, consumption is still increasing in India and Southeast Asia,[33] which compensates for the falls in other regions.[34]

Global coal consumption reached an all time high in 2023 at 8.5 billion tons.[35]Global coal consumption reached an all-time high in 2023, and is expected to fall in 2024.[36] Consumption declines in the United States and Europe, as well as developed economies in Asia[37] were offset by production increases in China, India and Indonesia.[36]

Switch to cleaner fuels and lower carbon electricity generation

editCoal-fired generation puts out about twice as much carbon dioxide—around a tonne for every megawatt hour generated—as electricity generated by burning natural gas at 500 kg of greenhouse gas per megawatt hour.[38] In addition to generating electricity, natural gas is also popular in some countries for heating and as an automotive fuel.

The use of coal in the United Kingdom declined as a result of the development of North Sea oil and the subsequent Dash for Gas during the 1990s. In Canada some coal power plants, such as the Hearn Generating Station, switched from coal to natural gas. In 2017, coal power in the United States provided 30% of the electricity, down from approximately 49% in 2008,[39][40][41] due to the plentiful supplies of low cost natural gas obtained by hydraulic fracturing of tight shale formations.[42]

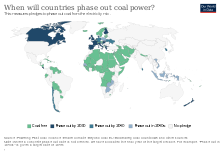

Coal phase-out by country

edit_ Coal >50% of grid electricity

_ Coal 10–50% of grid electricity

_ Coal 10–50% of grid electricity (PPCA member)

_ Coal <10% of grid electricity

_ Coal <10% of grid electricity (PPCA member)

_ Coal <0.1% of grid electricity

_ No data

Africa

editSouth Africa

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: implications of Eskom financial problems and Ramaphosa leadership. (June 2019) |

As of 2007, South Africa's power sector is the 8th highest global emitter of CO2.[44] In 2005/2006, 77% of South Africa's energy demand was directly met by coal.[45]

Since 2008, South Africa's government started funding solar water heating installations. As of January 2016, there have been 400 000 domestic installations in total, with free-of-charge installation of low-pressure solar water heaters for low-cost homes or low-income households which have access to the electricity grid, while other installations are subsidised.[46]

Americas

editCanada

editThis section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (March 2024) |

In November 2016, the Government of Canada announced plans to phase out coal-fired electricity generation by 2030.[47] As of 2024[update], only three provinces burned coal to generate electricity: Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Saskatchewan,[48] Canada aims to generate 90% of its electricity from non-emitting sources by 2030.[49] Already, it generates 82% from non-emitting sources.[50]

Beginning in 2005, Ontario planned coal phase-out legislation as a part of the province's electricity policy.[51] The province annually consumed 15 million tonnes of coal in large power plants to supplement nuclear power. Nanticoke Generating Station was a major source of air pollution,[52] and Ontario suffered "smog days" during the summer.[53] In 2007, Ontario's Liberal government committed to phasing out all coal generation in the province by 2014. Premier Dalton McGuinty said, "By 2030 there will be about 1,000 more new coal-fired generating stations built on this planet. There is only one place in the world that is phasing out coal-fired generation and we're doing that right here in Ontario."[54] The Ontario Power Authority projected that in 2014, with no coal generation, the largest sources of electrical power in the province will be nuclear (57 percent), hydroelectricity (25 percent), and natural gas (11 percent).[55] In April 2014, Ontario was the first jurisdiction in North America to eliminate coal in electricity generation.[56] The final coal plant in Ontario, Thunder Bay Generating Station, stopped burning coal in April 2014.[57] Alberta followed up in 2024 with phasing out its last coal power plant in Genesee.[58]

United States

editThis section needs to be updated. (May 2019) |

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (March 2024) |

In 2017, fossil fuels provided 81 percent of the energy consumed in the United States, down from 86 percent in 2000.[60]

| Year | Electrical generation from coal (TWh) |

Total electrical generation (TWh) |

% from coal |

Number of coal plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 1,933 | 3,858 | 50.1% | 633 |

| 2003 | 1,974 | 3,883 | 50.8% | 629 |

| 2004 | 1,978 | 3,971 | 49.8% | 625 |

| 2005 | 2,013 | 4,055 | 49.6% | 619 |

| 2006 | 1,991 | 4,065 | 49.0% | 616 |

| 2007 | 2,016 | 4,157 | 48.5% | 606 |

| 2008 | 1,986 | 4,119 | 48.2% | 598 |

| 2009 | 1,756 | 3,950 | 44.4% | 593 |

| 2010 | 1,847 | 4,125 | 44.8% | 580 |

| 2011 | 1,733 | 4,100 | 42.3% | 589 |

| 2012 | 1,514 | 4,048 | 37.4% | 557 |

| 2013 | 1,581 | 4,066 | 38.9% | 518 |

| 2014 | 1,582 | 4,094 | 38.6% | 491 |

| 2015 | 1,352 | 4,078 | 33.2% | 427 |

| 2016 | 1,239 | 4,077 | 30.4% | 381 |

| 2017 | 1,206 | 4,035 | 29.9% | 359 |

| 2018 | 1,149 | 4,181 | 27.5% | 336 |

| 2019 | 965 | 4,131 | 23.4% | 308 |

| 2020 | 773 | 4,010 | 19.3% | 284 |

| 2021 | 898 | 4,108 | 21.9% | 269 |

| References: [61] | ||||

In 2007, 154 new coal-fired plants were on the drawing board in 42 states.[62] By 2012, that had dropped to 15, mostly due to new rules limiting mercury emissions, and limiting carbon emissions to 1,000 pounds of CO2 per megawatt-hour of electricity produced.[63]

In July 2013, United States Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz outlined the Obama administration's policy on fossil fuels:

In the last four years, we’ve more than doubled renewable energy generation from wind and solar power. However, coal and other fossil fuels still provide 80 percent of our energy, 70 percent of our electricity, and will be a major part of our energy future for decades. That’s why any serious effort to protect our kids from the worst effects of climate change must also include developing, demonstrating and deploying the technologies to use our abundant fossil fuel resources as cleanly as possible.[64]

Then-US Energy Secretary Steven Chu and researchers for the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory have noted that greater electrical generation by non-dispatchable renewables, such as wind and solar, will also increase the need for flexible natural gas-powered generators, to supply electricity during those times when solar and wind power are unavailable.[65][66] Gas-powered generators have the ability to ramp up and down quickly to meet changing loads.[67]

In the US, many of the fossil fuel phase-out initiatives have taken place at the state or local levels.[citation needed]

In November 2021, US refused to sign up to coal phaseout agreement at the COP26 climate summit.[68][69]

California

editCalifornia's SB 1368 created the first governmental moratorium on new coal plants in the United States. The law was signed in September 2006 by Republican governor Arnold Schwarzenegger,[70] took effect for investor-owned utilities in January 2007, and took effect for publicly owned utilities in August 2007. SB 1368 applied to long-term investments (five years or more) by California utilities, whether in-state or out-of-state. It set the standard for greenhouse gas emissions at 1,100 pounds of carbon dioxide per megawatt-hour, equal to the emissions of a combined-cycle natural gas plant. This standard created a de facto moratorium on new coal, since it could not be met without carbon capture and sequestration.[71]

Maine

editOn 15 April 2008, Maine Governor John Baldacci signed LD 2126, "An Act To Minimize Carbon Dioxide Emissions from New Coal-Powered Industrial and Electrical Generating Facilities in the State." The law, which was sponsored by Rep. W. Bruce MacDonald (D-Boothbay), requires the Board of Environmental Protection to develop greenhouse gas emission standards for coal gasification facilities. It also puts a moratorium in place on building any new coal gasification facilities until the standards are developed.[72]

Oregon

editIn early March 2016, Oregon lawmakers approved a plan to stop paying for out-of-state coal plants by 2030 and require a 50 percent renewable energy standard by 2040.[73] Environmental groups such as the American Wind Energy Association and leading Democrats praised the bill.

Texas

editIn 2006, a coalition of Texas groups organized a campaign in favor of a statewide moratorium on new coal-fired power plants. The campaign culminated in a "Stop the Coal Rush" mobilization, including rallying and lobbying, at the state capital in Austin on 11 and 12 February 2007.[74] Over 40 citizen groups supported the mobilization.[75]

In January 2007, a resolution calling for a 180-day moratorium on new pulverized coal plants was filed in the Texas Legislature by State Rep. Charles Anderson (R-Waco) as House Concurrent Resolution 43.[76] The resolution was left pending in committee.[77] On 4 December 2007, Rep. Anderson announced his support for two proposed integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) coal plants proposed by Luminant (formerly TXU).[78]

Washington state

editWashington has followed the same approach as California, prohibiting coal plants whose emissions would exceed those of natural gas plants. Substitute Senate Bill 6001 (SSB 6001), signed on 3 May 2007, by Governor Christine Gregoire, enacted the standard.[79] As a result of SSB 6001, the Pacific Mountain Energy Center in Kalama was rejected by the state. However, a new plant proposal, the Wallula Energy Resource Center, shows the limits of the "natural gas equivalency" approach as a means of prohibiting new coal plants. The proposed plant would meet the standard set by SSB 6001 by capturing and sequestering a portion (65 percent, according to a plant spokesman) of its carbon.[79]

Hawaii

editHawaii officially banned the use of coal on September 12, 2020 when Governor Ige enacted Act 23 (SB2629). The law prohibited the issuing or renewing permits for coal power plants after December 31, 2022, and prohibited the extension of the power purchase agreement between AES and Hawaiian Electric. The power purchase agreement for the last coal plant, located on Oahu, expired September 1, 2022, this became the effective retirement date for the coal plant. On September 1, 2022, Hawaii will be completely coal free with the coal plant's retirement. Hawaii will transition to renewable energy to replace the energy produced by coal. The projects slated to replace the coal plant include nine solar plus battery projects, as well as a standalone battery storage project.

Asia

editChina

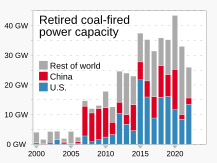

editAs of 2020, over half of the world's coal-generated electricity was produced in China.[80] In 2020 alone, China added 38 gigawatts of coal-fired power generation, over three times what the rest of the world built that year.[81]

China is confident of achieving a rich zero carbon economy by 2050.[82] In 2021, the government ordered all coal mines to operate at full capacity at all times, including holidays; approved new mines, and eliminated restrictions on coal imports.[83] In November 2021, China reached record coal production levels, breaking the previous historic record, established in October 2021.[84]

China's exceedingly high energy demand has pushed the demand for relatively cheap coal-fired power. Serious air quality deterioration has resulted from the massive use of coal and many Chinese cities suffer severe smog events.[85] [needs update]

As a consequence, the region of Beijing decided to phase out all its coal-fired power generation by the end of 2015,[86] a plan which it implemented with the closure of the Huaneng Beijing Thermal Power Plant in 2017. Despite this, however, the city imports most of its electricity from other coal-burning areas of the country,[87] and the Huaneng plant has been temporarily reopened several times.[88]

In 2009, China had 172 GW of installed hydro capacity, the largest in the world, producing 16% of China's electricity, the Eleventh Five-Year Plan has set a 300 GW target for 2020. China built the world's largest power plant of any kind, the Three Gorges Dam.

In addition to the huge investments in coal power, China has 32[89] nuclear reactors under construction, the highest number in the world.

Analysis in 2016, showed that China's coal consumption appears to have peaked in 2014.[90][91] In 2014, China consumed 2050 MTOE of coal; in 2020, 2060 MTOE; and the IEA projected 2021 China coal consumption at 2150 MTOE, or an increase of 5% vs. 2014.[92]

India

editThis section needs to be updated. (May 2019) |

India is the third largest consumer of coal in the world. India's federal energy minister is planning to stop importing thermal coal by 2018.[93] The annual report of India's Power Ministry has a plan to grow power by about 80 GW as part of their 11th 5-year plan, and 79% of that growth will be in fossil fuel–fired power plants, primarily coal.[94] India plans four new "ultra mega" coal-fired power plants as part of that growth, each 4000 MW in capacity. As of 2015[update], there are six nuclear reactors under construction. In the first half of 2016, the amount of coal-fired generating capacity in pre-construction planning in India fell by 40,000 MW, according to results released by the Global Coal Plant Tracker.[95] In June 2016, India's Ministry of Power stated that no further power plants would be required in the next three years, and "any thermal power plant that has yet to begin construction should back off."[96]

In cement production, carbon neutral biomass is being used to replace coal for reducing carbon foot print drastically.[97][98]

Indonesia

editThe Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership is a 20 billion dollar agreement to decarbonise Indonesia's coal-powered economy, launched on 15 November 2022 at the G20 summit.[99][100][101] This Just Energy Transition Partnership comes after the first such agreement, the South Africa JET-IP was announced in 2021 as a partnership with Germany, France, the UK and US.[102][103] The agreement with Indonesia involves all G7 countries as partners, including Canada, Italy and Japan. It also includes Denmark and Norway.[104][105] The JETP aims to develop a comprehensive investment plan (the JETP Investment and Policy Plan) to achieve Indonesia's decarbonisation goals.[106]

Under the JETP, Indonesia aims to reach net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases from electricity production by 2050, bringing forward its target by a decade, and reach a peak in those emissions by 2030. According to two think tanks, the $20bn allocated under the programme are insufficient for these goals.[107]

On the sideline of the same conference, the Asian Development Bank signed an agreement with Cirebon Electric Power to open discussions on accelerated retirement of the Cirebon Steam Power Plant.[108]Japan

editThis section needs to be updated. (June 2022) |

Japan, the world's third-largest economy, made a major move to use more fossil fuels in 2012, when the nation shut down nuclear reactors following the Fukushima accident. Nuclear, which had supplied 30 percent of Japanese electricity from 1987 to 2011, supplied only 2 percent in 2012 (hydropower supplied 8 percent). Nuclear electricity was replaced with electricity from petroleum, coal, and liquified natural gas. As a result, electricity generation from fossil fuels rose to 90 percent in 2012.[109] By 2021, Japan generated 30% of its electricity from coal.[110]

In January 2017, the Japanese government announced plans to build 45 new coal-fired power plants in the next ten years, largely to replace expensive electricity from petroleum power plants.[111] Japan has 140 coal plants of which 114 are classified as inefficient and as a result the government intends to shut these down by 2050 to meet its climate commitments.[112]

Philippines

editThe Philippines has stop issuing permits for the construction of new greenfield coal power plants in 2020.[113] Six provinces have passed ordinance banning coal power plants in their jurisdiction as of 2019 namely: Bohol, Guimaras, Ilocos Norte, Masbate, Negros Oriental, Occidental Mindoro, and Sorsogon[114]

The Department of Energy in December 2023 has urged for the voluntary early and orderly decommissioning or repurposing of existing coal-fired power plants in line of the Philippines' goal to have a 50 percent renewable energy share by 2040.[115][116]

Turkey

editIn 2019, the OECD said that energy and climate policies that are not aligned in future may prevent some assets from providing an economic return due to the transition to a low-carbon economy.[117] The average Turkish coal-fired power station is predicted to have higher long-run operating costs than renewables by 2030.[118] The insurance industry is slowly withdrawing from fossil fuels.[119]

In 2021 the World Bank said that a plan for a just transition away from coal is needed,[120] and environmentalists say it should be gone by 2030.[121] The World Bank has proposed general objectives and estimated the cost, but has suggested government do far more detailed planning.[122] According to a 2021 study by several NGOs if coal power subsidies were completely abolished and a carbon price introduced at around US$40 (which is lower than the 2021 EU Allowance) then all coal power stations would close down before 2030.[123] According to Carbon Tracker in 2021 $1b of investment on the Istanbul Stock Exchange was at risk of stranding, including $300 m for EÜAŞ.[124]: 12 Turkey has $3.2 billion in loans for its energy transition.[125] Small modular reactors have been suggested to replace coal power.[126] A 2023 study suggests the early 2030s and at the latest 2035 as a practical target for phase-out.[127] A 2024 study says that, although some plants would shutdown due to technological or economic obsolescence, a complete phase out by 2035 would require additional capital expenditure on electricity storage: however the study did not consider demand response or electricity trading with the EU.[128]

Some energy analysts say old plants should be shut down.[129] Three coal-fired power plants, which are in Muğla Province, Yatağan, Yeniköy and Kemerköy, are becoming outdated. However, if the plants and associated lignite mines were shut down, about 5000 workers would need funding for early retirement or retraining.[130] There would also be health[131] and environmental benefits,[132] but these are difficult to quantify as very little data is publicly available in Turkey on the local pollution by the plants and mines.[133][134] Away from Zonguldak mining and the coal-fired power plant employ most working people in Soma district.[135] According to Dr. Coşku Çelik "coal investments in the countryside have been regarded as an employment opportunity by the rural population".[136]

According to SwitchCoal a 20 billion dollar investment in converting 10 plants to solar, wind and batteries would make an extra 13 billion dollars profit over 30 years.[137] They assumed no carbon pricing and estimated lignite opex at 1 UScent per kWh.[138]: 24 They say this would save 35 megatonnes of emissions a year by installing 15GWp of solar, 8 of wind and 0.7 GW battery.[138]: 33

In 2024 thinktank Ember wrote that: “Four of the 38 OECD countries saw coal generation in 2023 fall by less than 30% from its peak: Japan, South Korea, Colombia and Mexico. Only one OECD country – Türkiye – has not yet passed the peak of coal power, setting a new record for coal generation in 2023.

Türkiye set a new coal generation record in 2023, overtaking Poland to become the second largest coal generator in Europe after Germany, with coal accounting for 37% of its electricity supply (118 TWh). However, coal is not booming in Türkiye: it was only 5% higher in 2023 than five years before in 2018. At that time, Türkiye was planning the world’s third-largest increase in coal power plants, but these have since been cancelled, avoiding a major increase in coal. Unlocking Türkiye’s untapped solar potential can help meet growing demand and replace coal power.”[139]: 9Vietnam

editAt the COP 26 in 2021, Vietnam pledged to phase out unabated coal power by the 2040s or soon thereafter.[140] This is part of the country's announcement to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. In December 2022, Vietnam joined the Just Energy Transition Partnership. Under this partnership, the country will receive $15.5 billion in the next 3–5 years to accelerate decarbonising its electricity sector, including shifting coal power use peak by 2030 instead of 2035. With coal contributing to about 50% of the electricity generation, Vietnam is facing numerous challenges to phase out coal while electricity demand is increasing around 10%/year. It could, however, ramp up the penetration of solar and wind power, particularly offshore wind, to replace coal power [141]

Europe

editThis section needs to be updated. (May 2019) |

In July 2014, CAN Europe, WWF European Policy Office, HEAL, EEB and Climate-Alliance Germany published a report calling for the decommissioning of the thirty most polluting coal-fired power plants in Europe.[142]

Austria

editAustria closed its last coal power plant in 2020.[143]

Bulgaria

editClosure is planned for 2038 but it is thought market forces will force it well before that.[144]

Belgium

editAfter the government denied a 2009 application to build a new power plant in Antwerp, the Langerlo power station burned its last ton of coal in March 2016, ending the use of coal fired power plants in Belgium.[145]

Denmark

editAs part of their Climate Policy Plan, Denmark stated that it will phase out oil for heating purposes and coal by 2030. Additionally, their goal is to supply 100% of their electricity and heating needs with renewable energy five years later (i.e. 2035).[146]

Finland

editIn 2019, Finland enacted a ban of coal use for energy purposes starting on 1 May 2029, ahead of the 2030 schedule discussed earlier.[147][148] As of 2020, coal represented only 4.4% of electricity generated in the country.[149] Finland is a founding member of the Powering Past Coal Alliance along 18 other countries.[150][151]

France

editThe French government intends to close or convert the nation's last four coal plants by 2022.[152][153] In April 2021 the Le Havre coal plant unit was shuttered.[154]

In December 2017, to fight against global warming, France adopted a law banning new fossil fuel exploitation projects and closing current ones by 2040 in all of its territories. France thus became the first country to programme the end of fossil fuel exploitation.[155][156]

Germany

editThis section may be too long and excessively detailed. (April 2024) |

Anthracite mining has long been subsidized in Germany, reaching a peak of €6.7 billion in 1996 and dropping to €2.7 billion in 2005 due to falling output. These subsidies represented a burden on public finances and implied a substantial opportunity cost, diverting funds away from other, more beneficial public investments.[157]

In February 2007, Germany announced plans to phase out hard coal-industry subsidies by 2018, a move which ended hard coal mining in Germany.[158][159][160][161][162] This exit was later than the EU-mandated end by 2014.[163] Solar and wind are major sources of energy and renewable energy generation, around 15% as of December 2013,[164] and growing.

In 2007, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the First Merkel cabinet (CDU/CSU and SPD) agreed to legislation to phase out Germany's hard coal mining sector. That did not mean that they supported phasing out coal in general. There were plans to build about 25 new plants in the coming years. Most German coal power plants were built in the 1960s, and have a low energy efficiency. Public sentiment against coal power plants was growing and the construction or planning of some plants was stopped.[165][159][160][161][162] A number are under construction and still being built. No concrete plan is in place to reduce coal-fired electricity generation. As of October 2015, the remaining coal plants still under planning include: Niederaussem, Profen, and Stade. The coal plants then under construction included: Mannheim and Kraftwerk Datteln IV (it started 30 May 2020). Between 2012 and 2015, six new plants went online.[166] All of these plants are 600–1800 MWe.[167]

In 2014, Germany's coal consumption dropped for the first time, having risen each year since the low during the 2009 recession.[168]

A 2014 study found that coal is not making a comeback in Germany, as is sometimes claimed. Rather renewables have more than offset the nuclear facilities that have been shut down as a result of Germany's nuclear power phase-out (Atomausstieg). Hard coal plants now face financial stringency as their operating hours are cut back by the market. But in contrast, lignite-fired generation is in a safe position until the mid-2020s unless government policies change. To phase-out coal, Germany should seek to strength the emissions trading system (EU-ETS), consider a carbon tax, promote energy efficiency, and strengthen the use of natural gas as a bridge fuel.[169]

In 2016, the Third Merkel cabinet and affected lignite power plant operators Mibrag, RWE, and Vattenfall reached an understanding (Verständigung) on the transfer of lignite power plant units into security standby (Überführung von Braunkohlekraftwerksblöcken in die Sicherheitsbereitschaft). As a result, eight lignite-fired power plants are to be mothballed and later closed, with the first plant scheduled to cease operation in October 2016 and the last in October 2019. The affected operators will receive state compensation for foregone profits. The European Commission has declared government plans to use €1.6 billion of public financing for this purpose to be in line with the European Union's rules on state aid.[170]

A 2016 study found that the phase-out of lignite in Lusatia (Lausitz) by 2030 can be financed by future owner EPH in a manner that avoids taxpayer involvement. Instead, liabilities covering decommissioning and land rehabilitation could be paid by EPH directly into a foundation, perhaps run by the public company LMBV. The study calculates the necessary provisions at €2.6 billion.[171][172]

In November 2016, the German utility STEAG announced it will be decommissioning five coal-fired generating units in North Rhine-Westphalia and Saarland due to low wholesale electricity prices.[173][174]

A coal phase-out for Germany is implied in Germany's Climate Action Plan 2050, environment minister Barbara Hendricks said in an interview on 21 November 2016. "If you read the Climate Action Plan carefully, you will find that the exit from coal-fired power generation is the immanent consequence of the energy sector target. ... By 2030 ... half of the coal-fired power production must have ended, compared to 2014", she said.[175][176]

Plans to cut down the ancient Hambach Forest to extend the Hambach surface mine in 2018 have resulted in massive protests. On 5 October 2018 a German court ruled against the further destruction of the forest for mining purposes. The ruling states, the court needs more time to reconsider the complaint. Angela Merkel, the chancellor of Germany, welcomed the court's ruling. The forest is located approximately 29 km west of the city center of Cologne (specifically Cologne Cathedral).[177]

In January 2019 the German Commission on Growth, Structural Change and Employment initiated Germany's plans to entirely phase out and shut down the 84 remaining coal-fired plants on its territory by 2038.[178]

In May 2020, the 1100 MW Datteln 4 coal-fired power plant was added to the German grid after nearly a 10-year delay in construction.[179][180]

In the first half of 2021, coal was the largest source of power generation in Germany due to less wind than in the years before.[181]

As coal is continuously phased-out in Germany, natural gas is increasingly replacing coal-burning power plants. In late 2021, a record-breaking surge in energy prices in Europe, particularly for natural gas and refined petroleum products, has put this development into question. While the European Union is gradually cutting down on its dependence on fossil fuels, a shift to a green economy has not happened as swiftly as expected. Since many countries in Europe resort to natural gas in order to build their green economies, elevated prices for natural gas have been viewed as a stumbling block for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[182]

Italy

editAs of 2020, Italy still has nine coal power plants, for a total capacity of 7702 MW. Enel, Italy's largest power generator, intends to shut down three power plants in early 2021.[183][184]

Netherlands

editThis section needs to be updated. The reason given is: legal action. (February 2021) |

On 22 September 2016, the States General of the Netherlands voted for a 55% cut in CO2 emissions by 2030, a move which would require the closure of the country's five coal-fired power plants. However, the vote is not binding on the government.[185] In December 2019 the Dutch senate banned coal for power generation by 2030 at the latest.[186][187]

Poland

editAs of March 2024 the date is still being discussed.[188]

Portugal

editOn 20 November 2021 Portugal turned off the last remaining coal station (Pego), making Portugal coal free.[189]

Spain

editIn October 2018, the First government of Pedro Sánchez and Spanish trade unions settled an agreement to close ten Spanish coal mines at the end of 2018. The government pre-engaged to spend 250 million Euro to pay for early retirements, occupational retraining and structural changes. In 2018, about 2.3 percent of the electric energy produced in Spain was produced in coal-fired power stations.[190]

Sweden

editIn 2019 coal was still used to a limited extent to fuel three co-generation plants in Sweden that produced electricity and district heating. The operators of these plants planned to phase out coal by 2020,[191] 2022[192] and 2025[193] respectively. In August 2019 one of the three remaining coal burning power producers announced that they had phased out coal prematurely in 2019 instead of 2020.[194] Värtaverket was scheduled to close in 2022, but closed in 2020.[195] This was the last coal plant in Sweden, and its closure made Sweden coal free.

In addition to heat and power coal is also used for steel production, there are long-term plans to phase out coal from steel production: Sweden is constructing hydrogen-based pilot steel plant to replace coke and coal usage in steel production.[196] Once this technology is commercialized with the hydrogen generated from renewable energy sources (biogas or electricity), the carbon foot print of steel production would reduce drastically.[98]

United Kingdom

editThe last coal power station in the United Kingdom (Ratcliffe-on-Soar Power Station in England) stopped operating on 30 September 2024.[197] Scotland's last coal power station closed in 2016,[198] Wales' last coal power station closed in December 2019[199] and Northern Ireland's last coal power station closed in September 2023.[200]

Coal power dominated the UK's electricity mix for decades but began to decline after the Dash for Gas in the 1990s, with significant competition from new combined cycle gas turbines. The trend continued after subsequent environmental laws brought in during the early 21st century to improve air quality, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and incentivise the rollout of renewable energy.[197] In generating capability there was initially the closure of the Hinton Heavies, followed by the closure or conversion to biomass of the remaining coal plants by 2024. In the final few years of coal power in the UK, in 2018 it was less than at any time since the Industrial Revolution. The first "coal free day" took place in 2017. Coal supplied 5.4% of UK electricity in 2018, down from 30% in 2014,[201] and 70% in 1990.[197] Gas-fired power stations continue to provide some firm service.[202]

Oceania

editAustralia

editThis section needs to be updated. (May 2020) |

The Australian Greens party have proposed to phase out coal power stations. The Greens NSW proposed an immediate moratorium on coal-fired power stations and want to end all coal mining and coal industry subsidies. The Australian Greens and the Australian Labor Party also oppose nuclear power. The Federal Government and Victorian State Government want to modify existing coal-fired power stations into clean coal power stations.[citation needed] The Federal Labor government extended the mandatory renewable energy targets, an initiative to ensure that new sources of electricity are more likely to be from wind power, solar power and other sources of renewable energy in Australia. Australia is one of the largest consumers of coal per capita, and also the largest exporter. The proposals are strongly opposed by industry, unions[203] and the main Opposition Party in Parliament (now forming the party in government after the September 2013 election).

New Zealand

editThis section needs to be updated. (February 2021) |

In October 2007, the Clark Labour government introduced a 10 year moratorium on new fossil fuel thermal power generation.[204] The ban was limited to state-owned utilities, although an extension to the private sector was considered. The new government under MP John Key (NZNP) elected in the 2008 New Zealand general election, repealed this legislation.[citation needed]

In 2014, almost 80 percent of the electricity produced in New Zealand was from sustainable energy.[205] On 6 August 2015, Genesis Energy Limited announced that it would close its two last coal-fired power stations.[206]

See also

edit- Beyond Coal – a campaign by the Sierra Club to promote renewable energy instead of coal[207]

- Big Coal

- Burning the Future: Coal in America

- The Coal Question

- Powering Past Coal Alliance

References

edit- ^ a b "Retired Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ Global Energy Monitor; CREA; E3G; Reclaim Finance; Sierra Club; SFOC; Kiko Network; CAN Europe; Bangladesh Groups; ACJCE; Chile Sustentable (5 April 2023). Boom and Bust Coal: Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline (PDF) (Report). p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2023.

- ^ "New Coal-fired Power Capacity by Country / Global Coal Plant Tracker". Global Energy Monitor. 2023. Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. — Global Energy Monitor's Summary of Tables (archive)

- ^ "Coal Phase Out". climateanalytics.org. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "How to accelerate the energy transition in developing countries". World Economic Forum. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Emissions – Global Energy & CO2 Status Report 2019 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Jaeger, Joel (30 November 2023). "These 10 Countries Are Phasing Out Coal the Fastest".

- ^ Shan, Lee Ying (10 January 2024). "World's two largest coal consumers won't be weaning off the fossil fuel anytime soon". CNBC. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ "Guest post: Coal-project financing outside of China hits 12-year low". Carbon Brief. 10 July 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Rauner, Sebastian; Bauer, Nico; Dirnaichner, Alois; Dingenen, Rita Van; Mutel, Chris; Luderer, Gunnar (23 March 2020). "Coal-exit health and environmental damage reductions outweigh economic impacts". Nature Climate Change. 10 (4): 308–312. Bibcode:2020NatCC..10..308R. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0728-x. ISSN 1758-6798. S2CID 214619069.

- ^ "How to replace coal power with renewables in developing countries". Eco-Business. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "G7 commits to end support for coal-fired power stations this year". euronews. 21 May 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "Phasing out coal could generate 'social benefits' worth $78 trillion | Imperial News | Imperial College London". Imperial News. June 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ^ "The Great Carbon Arbitrage". IMF. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "Coal dumped as IEA turns to wind and solar to solve climate challenge". Renew Economy. 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Coal exit benefits outweigh its costs — PIK Research Portal". www.pik-potsdam.de. Archived from the original on 24 March 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ "In coal we trust: Australian voters back PM Morrison's faith in fossil fuel". Reuters. 19 May 2019. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019.

- ^ Rockström, Johan; et al. (2017). "A roadmap for rapid decarbonization" (PDF). Science. 355 (6331): 1269–1271. Bibcode:2017Sci...355.1269R. doi:10.1126/science.aah3443. PMID 28336628. S2CID 36453591.

- ^ "Time for China to Stop Bankrolling Coal". The Diplomat. 29 April 2019.

- ^ Sartor, O. (2018). Implementing Coal Transitions Insights from Case Studies of Major Coal-Consuming Economies. IDDRI and Climate Strategies.

- ^ "Germany agrees to end reliance on coal stations by 2038". The Guardian. 26 January 2019.

- ^ Srivastav, Sugandha; Zaehringer, Michael (16 May 2024). "The Economics of Coal Phaseouts: Auctions as a Novel Policy Instrument for the Energy Transition". Climate Policy. 24 (6): 754–765. arXiv:2406.14238. Bibcode:2024CliPo..24..754S. doi:10.1080/14693062.2024.2358114.

- ^ "Spain to close most coalmines in €250m transition deal". The Guardian. 26 October 2018.

- ^ "Pacific nations under climate threat urge Australia to abandon coal within 12 years". The Guardian. 13 December 2018.

- ^ "The dirtiest fossil fuel is on the back foot". The Economist. 3 December 2020. ISSN 0013-0613.

- ^ Do, Thang Nam; Burke, J Paul (2023). "Phasing out coal power in a developing country context: Insights from Vietnam". Energy Policy. 176 (May 2023 113512): 113512. Bibcode:2023EnPol.17613512D. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113512. hdl:1885/286612. S2CID 257356936.

- ^ "Coal". International Energy Agency. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Ambrose, Jillian (11 April 2024). "World's coal power capacity rises despite climate warnings". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Dewan, Angela (30 April 2024). "The world's most advanced economies just agreed to end coal use by 2035 – with a catch". CNN. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ Ambrose, Jillian (30 April 2024). "G7 agree to end use of unabated coal power plants by 2035". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Rapier, Robert. "Coal Demand Rises, But Remains Below Peak Levels". Forbes. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "Executive summary – Accelerating Just Transitions for the Coal Sector – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ "Global coal demand expected to decline in coming years - News". IEA. 15 December 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2023.

- ^ "Coal Information: Overview". Paris: International Energy Agency. July 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Global coal use at all-time high in 2023 - IEA". Reuters. 2023.

- ^ a b "Supply – Coal 2023 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Frangoul, Frangoul (27 July 2023). "IEA says coal use hit an all-time high last year — and global demand will persist near record levels". CNBC. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "Electricity emissions around the world". 23 April 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". U.S. Energy Information Administration. 18 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Lipton, Eric (29 May 2012). "Even in Coal Country, the Fight for an Industry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ "Figure ES 1. U.S. Electric Power Industry Net Generation". Electric Power Annual with data for 2008. U.S. Energy Information Administration. 21 January 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2010.

- ^ Key World Energy Statistics (PDF) (Report). Paris: International Energy Agency. 2014. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Electricity Data Explorer | Open Source Global Electricity Data". Ember.

- ^ "Carbon Dioxide Emissions From Power Plants Rated Worldwide". Sciencedaily.com.

- ^ "Department of Minerals and Energy: Energy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ Rycroft, Mike (14 January 2016). "Solar water heater rollout programme gains momentum". Ee.co.za. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Canada plans to phase out coal-powered electricity by 2030". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. 21 November 2016. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "Coal phaseout in Canada – Ex-colleagues helping miners' job transition". Balkan Green Energy News. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Canada, Environment and Climate Change (24 November 2016). "Powering our future with clean electricity". aem. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Canada, Natural Resources (6 October 2017). "electricity-facts". www.nrcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "Ontario's Coal Phase-out Will Have Drastic Consequences, Say The Thinking Companies". www.businesswire.com. 16 February 2005. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Nanticoke plant is province's biggest polluter, study finds". Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ Foran, Vanessa (19 January 2017). "Air is cleaner, Ontarians healthier since Ontario shut down coal". CNW Group on behalf of Asthma Society of Canada. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Ont. Liberals promise to close coal plants by 2014". CTV News. 18 June 2007. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ Ontario Power Authority, Long-Term Energy Plan 2013, module 3, 2014.

- ^ "Creating Cleaner Air in Ontario". news.ontario.ca. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Ontario Power Generation Moves to Cleaner Energy Future : Thunder Bay Station Burns Last Piece of Coal" (PDF). Opg.com. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Alberta is no longer using coal to generate electricity". CTV News Edmonton. 18 June 2024. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ Rivera, Alfredo; King, Ben; Larsen, John; Larsen, Kate (10 January 2023). "Preliminary US Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimates for 2022". Rhodium Group. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Figure 4. (Archive including images) Also presented in The New York Times.

- ^ US Energy Information Administration, Primary energy consumption by source, accessed 5 April 2018

- ^ "Electric Power Annual (Section 3.1A and 4.1)". US Energy Information Administration. November 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ "Eco Concern: Coal Plant Boom". Wired. Dallas. Associated Press. 15 October 2006. Archived from the original on 14 December 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Keith; Smith, Rebecca; Maher, Kris (28 March 2012). "New Rules Limit Coal Plants". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Ernest Moritz, Excerpts of Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz’s Remarks at National Energy Technology Laboratory in Morgantown, United States Department of Energy, 29 July 2013.

- ^ April Lee and others, Opportunities for synergy between natural gas and renewable energy, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Dec. 2012.

- ^ John Funk, DOE boss says shale gas could benefit wind and solar, Cleveland Plain Dealer, 18 January 2012.

- ^ US EIA, Natural gas-fired combustion turbines are generally used to meet peak electricity load, 1 October 2013.

- ^ "'End of coal in sight' as more than 40 nations join new pact". Financial Times. 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "COP26: More than 40 countries pledge to quit coal". BBC News. 4 November 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ "SB 1368 Emission Performance Standards". Energy.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "California Takes on Power Plant Emissions: SB 1368 Sets Groundbreaking Greenhouse Gas Performance Standard," Natural Resources Defense Council Fact Sheet, August 2007.

- ^ Rhonda Erskine, "Maine Governor Baldacci Signs Bill to Reduce Carbon Dioxide Emissions," [permanent dead link] WCSH WCSH6.com, 15 April 2008

- ^ "Oregon lawmakers approve far-reaching climate change bill". MSN. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ ""Stop the Coal Rush" Rally & Lobby Day Set for February 11 & 12" (Press release). Austin: Sierra Club Lone Star Chapter. 25 January 2007. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008.

- ^ "StopTheCoalRush – Hot Rush in Marketing". stopthecoalrush.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- ^ "Text of HCR 43" (PDF).

- ^ "Texas Legislature Online – 80(R) History for HCR 43". state.tx.us.

- ^ "Representative Anderson Applauds Luminant Action on IGCC" (Press release). Charles Anderson. 4 December 2007. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008.

- ^ a b Russell, Christina (15 November 2007). "Wallula coal plant proposal controversial among students, faculty". Whitman Pioneer. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Whitman College Pioneer, 11/15/07

- ^ "China generated over half world's coal-fired power in 2020: study". Reuters. 28 March 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

China generated 53% of the world's total coal-fired power in 2020, nine percentage points more that five years earlier

- ^ "China generated half of global coal power in 2020: study". Deutsche Welle. 29 March 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

new coal-fired power installations reached 38.4 GW in 2020. That's more than three times the amount built by the rest of the world

- ^ "China 2050: A Fully Developed Rich Zero-Carbon Economy" (PDF). Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Chuin-Wei Yap (20 October 2021). "China Takes the Brakes Off Coal Production to Tackle Power Shortage". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

China has ordered all coal mines to operate at full capacity [...] It has ordered all coal mines to operate at full capacity even during holidays, issued approvals for new mines [...] China's rollback of restrictions on mining and imports of coal

- ^ "China coal output hits record in Nov to ensure winter supply". Reuters. 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Why is the smog in China so bad?". popsci.com. 18 March 2019.

- ^ "China's Beijing city to abolish coal-fired power plants by end 2014 – Electric Power – Platts News Article & Story". Platts.com.

- ^ "Beijing's green electricity credentials questioned". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ "Beijing Restarts Coal-Fired Power Plant as Extreme Cold Grips Capital - Caixin Global". www.caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ "PRIS – Country Details". Iaea.org. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (25 July 2016). "China's coal peak hailed as turning point in climate change battle". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ Qi, Ye; Stern, Nicholas; Wu, Tong; Lu, Jiaqi; Green, Fergus (25 July 2016). "China's post-coal growth" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 9 (8): 564–566. Bibcode:2016NatGe...9..564Q. doi:10.1038/ngeo2777.

- ^ "Coal consumption by region, 2000 to 2021 – Charts – Data & Statistics".

- ^ "Thermal coal imports will stop by 2017: Goyal". 15 May 2015.

- ^ Annual Report 2008–09 (PDF) (Report). New Delhi: Ministry of Power. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Alister Doyle, "Global coal power plans fall in 2016, led by China, India: study," Reuters, 6 September 2016

- ^ "India won't need extra power plants for next three years, says government report", The Economic Times, 2 June 2016

- ^ "Lafargeholcim – Geocycle secures biomass needs from local farmers in India". Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b "New IEA Report: Renewable Energy for Industry". 10 November 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Indonesia Just Energy Transition Partnership Launched at G20". GOV.UK. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Junida, Ade Irma; Ruhman, Fadhli (8 November 2022). Nasution, Rahmad (ed.). "Indonesia negotiating funding cooperation for energy transition". antaranews.com. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "G7 offered Vietnam and Indonesia $15B to drop coal. They said 'maybe'". POLITICO. 26 October 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "Deutsche G7-Präsidentschaft treibt ambitionierte Just Energy Transition Partnerships voran". Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (in German). Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ Lo, Joe (7 November 2022). "As Cop27 kicks off, where are the coal to clean deals at?". Climate Home News. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ "U.S., Japan to offer Indonesia $15 bln in energy transition funds-Bloomberg News". Reuters. 11 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Press corner". European Commission - European Commission. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "Indonesia JETP - Accelerating Indonesia's Decarbonisation Timeline". Mayer Brown. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ "How Indonesia, a major fossil-fuel user, plans to decarbonise". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ "ADB and Indonesia Partners Sign Landmark MOU on Early Retirement Plan for First Coal Power Plant Under Energy Transition Mechanism". Asian Development Bank. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ "Japan’s fossil-fueled generation remains high because of continuing nuclear plant outages", US Energy Information Administration, 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Despite the Biden Administration's Wishes, Coal Won't Go Away". 17 November 2021.

- ^ Babs McHugh, "Japan plans to build 45 coal power plants in next decade," Platts, 3 February 2017.

- ^ "Japan to shut or mothball 100 ageing coal-fired power plants: Yomiuri". Reuters. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "No more new coal plant applications under latest PH energy policy". Rappler. 27 October 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Standard, Manila (9 December 2019). "Occidental Mindoro bans coal plants". Manila Standard. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Mercurio, Richmond (7 December 2023). "DOE pushing for deactivation of coal-fired power plants". The Philippine Star. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Velasco, Myrna (6 December 2023). "PH opts for coal plants' phasedown, instead of phaseout". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ EfimovaMazurMigottoRambali (2019), p. 39.

- ^ "Powering down coal: Navigating the economic and financial risks in the last years of coal power". Carbon Tracker Initiative. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Fosil yakıtlar ve kömür sigorta portföyünden çıkıyor". www.patronlardunyasi.com. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Erkuş, Sevil (15 November 2021). "World Bank official praises Turkey's GDP growth". Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Environmental organizations from across Turkey called: We want a "fair phase-out" of coal by 2030 | STGM". www.stgm.org.tr. 6 September 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ Türkiye - Country Climate and Development Report (Report). World Bank. 13 June 2022.

- ^ "First Step in the Pathway to a Carbon Neutral Turkey: Coal Phase out 2030". Sustainable Economics and Finance Association. APLUS Energy for Europe Beyond Coal, Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, Sustainable Economics and Finance Research Association (SEFiA), WWF-Turkey (World Wildlife Fund), Greenpeace Mediterranean, 350.org and Climate Change Policy and Research Association. November 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Taking Stock of Coal Risks". Carbon Tracker. November 2021. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- ^ "EU's looming carbon tax nudged Turkey toward Paris climate accord, envoy says". POLITICO. 6 November 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Turkey in talks with US to buy small nuclear reactors, weaning itself off coal". Al Arabiya English. 21 December 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ Kat, Bora; Sahin, Umit; Teimourzadeh, Saeed; Tor, Osman B.; Voyvoda, Ebru; Yeldan, A. Erinc (2023). "Coal Phase-out in the Turkish Power Sector towards Net-zero Emission Targets: An Integrated Assessment of Energy-Economy-Environment Modeling". Presented during the 26th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis (Bordeaux, France). Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "How Realistic Are Coal Phase-Out Timeline Targets for Turkey?" (PDF).

- ^ Direskeneli, Haluk (19 March 2023). "Sustainable Energy In Turkey – OpEd". Eurasia Review. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ "The Real Costs of Coal: Muğla". Climate Action Network Europe. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Ugurtas, Selin (17 April 2020). "Coronavirus outbreak exposes health risks of coal rush". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Beyaz Çamaşır Asılamayan Şehir (ler)" [Cities where washing cannot be hung out to dry]. Sivil Sayfalar (in Turkish). 13 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Hattam, Jennifer (17 September 2019). "Turkey: Censorship fogging up pollution researchers' work". DW.COM. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ European Commission (2019), p. 93: "There are still complaints about the application of the rule of law in court decisions on environmental issues and about public participation and the right to environmental information."

- ^ "Soma Termik Santrali'nde emisyon oranlarını Bakanlığa anlık bildiren sistem kuruldu". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Extractivism, State and Socio-Environmental Struggles: Turkey and Ecuador". The Media Line. 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ "Coal power plants in Türkiye | SwitchCoal". www.switchcoal.org. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Press". www.switchcoal.org. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Jones, Dave (1 October 2024). Coal generation in OECD countries falls below half of its peak (Report). Ember.

- ^ Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul J (2023). "Phasing out coal power in a developing country context: Insights from Vietnam". Energy Policy. 176 (113512, May 2023). Bibcode:2023EnPol.17613512D. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113512. hdl:1885/286612.

- ^ Do, Thang Nam; Burke, Paul J; Hughes, Llewelyn; Ta, Dinh Thi (2022). "Policy options for offshore wind power in Vietnam". Marine Policy. 141 (July 2022, 105080). Bibcode:2022MarPo.14105080D. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105080. hdl:1885/275544.

- ^ Gutmann, Kathrin; Huscher, Julia; Urbaniak, Darek; White, Adam; Schaible, Christian; Bricke, Mona (July 2014). Europe's dirty 30: how the EU's coal-fired power plants are undermining its climate efforts (PDF). Brussels, Belgium: CAN Europe, WWF European Policy Office, HEAL, the EEB, and Climate-Alliance Germany. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Wind is now the largest power source in Iowa and Kansas – Electrek". Electrek. 20 April 2020.

- ^ "Market economics to cut Bulgaria's coal use before 2038 deadline – minister". Reuters.

- ^ Dascalu, c. (5 April 2016). "Belgium says goodbye to coal power use..." Can Europe.

- ^ The Danish Climate Policy Plan: Towards a low carbon society (Report). The Danish Government. August 2013. ISBN 978-87-93071-29-2. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ "Finland approves ban on coal for energy use from 2029". Reuters. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Morgan, Sam. "Finland confirms coal exit ahead of schedule in 2029". Euractiv. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Electricity generation – Energiateollisuus, retrieved 5 March 2021

- ^ Finland co-founds a Powering Past Coal alliance in Bonn Climate Conference, retrieved 5 March 2021

- ^ POWERING PAST COAL ALLIANCE: DECLARATION (PDF), retrieved 5 March 2021

- ^ "France remains committed to 2022 coal phase-out". www.endseurope.com. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Felix, Bate (22 March 2019). "France's EDF in race to convert Cordemais plant from coal to biomass". Reuters. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "France's EDF closes a 580 MW coal-fired power unit in Le Havre | Enerdata". www.enerdata.net. April 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Agence France-Presse, "France bans fracking and oil extraction in all of its territories ", The Guardian, 20 December 2017 (page visited on 30 December 2017).

- ^ (in French) "La France devient le premier pays à programmer la fin des hydrocarbures", Radio télévision suisse, 30 December 2017 (page visited on 30 December 2017).

- ^ Frondel, Manuel; Kambeck, Rainer; Schmidt, Christoph M (2007). "Hard coal subsidies: a never-ending story?" (PDF). Energy Policy. 35 (7): 3807–3814. Bibcode:2007EnPol..35.3807F. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2007.01.019. hdl:10419/18604.

- ^ "Daten und Fakten zu Braun- und Steinkohlen". Umweltbundesamt. 7 December 2017. [dead link]

- ^ a b "End of an Industrial Era: Germany to Close its Coal Mines". Der Spiegel. Spiegel Online. 30 January 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ a b "German plan to close coal mines". BBC News. 29 January 2007. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Breaking News, World News & Multimedia". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ a b "The World From Berlin: Good Riddance to Coal Mining". Der Spiegel. Spiegel Online. 30 January 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Germany stays firm on plan to scrap coal subsidies in 2018". Dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 17 November 2010.

- ^ "Germany targets 47% Renewable Energy Production by 2020". Rncos.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Germany to shut down coal mines in 2018". Forbes. 30 January 2007.[dead link]

- ^ i.e. Kraftwerk Wilhelmshaven in 201.

- ^ "The demise of coal in Germany and globally". 15 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ^ BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015 (PDF). London, UK: BP. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Jungjohann, Arne; Morris, Craig (June 2014). The German coal conundrum (PDF). Washington, DC, US: Heinrich Böll Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "EU Commission Approves State Aid for Closure of Lignite-Fired Power Plants". German Energy Blog. 31 May 2016. Archived from the original on 2 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "IEEFA Europe: Blueprint for a Lignite Phase-Out in Germany". Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. 22 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ Wynn, Gerard; Julve, Javier (September 2016). A Foundation-Based Framework for Phasing Out German Lignite in Lausitz (PDF). Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA). Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Utility to shut down five coal plants". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, Germany. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Steag: Energiekonzern schaltet fünf Kohlekraftwerke ab" [Steag: Energy corporation switches off five coal-fired power plants]. Handelsblatt (in German). Düsseldorf, Germany. 2 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Coal exit is in the Climate Action Plan". Clean Energy Wire (CLEW). Berlin, Germany. 21 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Götze, Susanne; Schwarz, Susanne (21 November 2016). "Kohleausstieg steht im Klimaschutzplan" [Coal exit is in the Climate Action Plan]. klimaretter.info (in German). Berlin, Germany. Archived from the original on 22 November 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Smith-Spark, Laura. "Hambach Forest clearance halted by German court". CNN. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Kirschbaum, Erik (26 January 2019). "Germany to close all 84 of its coal-fired power plants, will rely primarily on renewable energy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

Germany, one of the world's biggest consumers of coal, will shut down all 84 of its coal-fired power plants over the next 19 years to meet its international commitments in the fight against climate change, a government commission said Saturday.

- ^ Solomon, Erika. "Environmentalists on back foot as Germany's newest coal plant opens". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "Climate activists protest Germany's new Datteln 4 coal power plant". Detsche Welle. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "Germany: Coal tops wind as primary electricity source | DW | 13.09.2021". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ "Why Europe's energy prices are soaring and could get much worse". Euronews. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Enel lines up three Italian coal closures for early 2021 | S&P Global Platts". 9 September 2020.

- ^ "Italy: Enel lines up three Italian coal closures for early 2021". 14 September 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Neslen, Arthur (23 September 2016). "Dutch parliament votes to close down country's coal industry". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "Vattenfall's last coal power plant in the Netherlands is closing". Vattenfall. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "State aid: Commission approves compensation for early closure of coal fired power plant in the Netherlands". European Commission – European Commission. 12 May 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "A Vision for Poland's Clean Energy Transition". Clean Air Task Force. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Portugal goes coal free". www.theportugalnews.com. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ theguardian.com 26. October 2018: Spain to close most coal mines after striking €250m deal

- ^ "Mälarenergi ska vara fossilfritt 2020". www.energinyheter.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Kolet ska bort från Värtaverket 2022". Mitt i Stockholm (in Swedish). 15 October 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "E.ON fasar ut fossilt och investerar flera hundra miljoner i nytt värmeverk i Norrköping". Bioenergitidningen (in Swedish). 26 March 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ Radio, Sveriges (21 August 2019). "Mälarenergi har slutat elda kol – P4 Västmanland". Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Andersson, Anna (2020). "Det koleldade kraftvärmeverket KVV6 vid Värtaverket har varit i drift och levererat värme och el till stockholmarna sedan 1989. Nu stängs det. – Stockholm Exergi". www.stockholmexergi.se (in Swedish).

- ^ "Sweden starts construction on fossil fuel-free steel plant". Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "UK to close last coal power station after 142 years". BBC News. 30 September 2024.

- ^ "Longannet switch-off ends coal-fired power production in Scotland". BBC News. 24 March 2016.

- ^ Clowes, Ed (11 December 2019). "Wales' last coal power plant to go dark on Friday". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "Kilroot: 'Electricity disruption unlikely' as power station closes". BBC News. 29 September 2023.

- ^ Evans, Simon (10 February 2016). "Countdown to 2025: Tracking the UK coal phase out". Carbon Brief. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ "UK coal plants must close by 2025, Amber Rudd announces". 18 November 2015.

- ^ Colley, Peter (Winter 2008). "We need ALL the solutions". Australian Options. No. 53. pp. 16–20. ISSN 1324-0749. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012.

- ^ "New Zealand issues ten-year ban on new thermal power plants". Power Engineering. PennWell Corporation. 11 October 2007. ISSN 0032-5961. Archived from the original on 20 June 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand will shut down its last large coal-fired power generators in 2018". Sciencealert.com. 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Market release: GNE announces timetable to end coal-fired generation in New Zealand" (PDF).

- ^ "Beyond Coal". sierraclub.org.

Sources

edit- Efimova, Tatiana; Mazur, Eugene; Migotto, Mauro; Rambali, Mikaela; Samson, Rachel (February 2019). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019. OECD (Report). OECD Environmental Performance Reviews. doi:10.1787/9789264309753-en. ISBN 9789264309760.

- European Commission (May 2019). "Turkey 2019 Report" (PDF).