| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

Margery Olivier | |

|---|---|

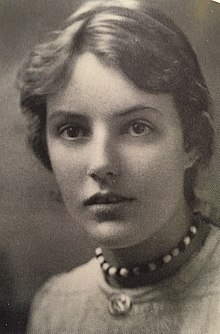

Margery Olivier ca. 1906 | |

| Born | April 1886 |

| Died | 1974 |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Newnham College, Cambridge |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | List

|

Margery Olivier (1886-1974) was the daughter of a Victorian English politician and one of four sisters noted for their progressive ideas, beauty and associations with both Rupert Brooke and his Cambridge circle of Neo-pagans, as well as the Bloomsbury Group. Born in London, Margery Olivier was raised and home schooled in Jamaica and Limpsfield, Surrey.

Family origin edit

The Honourable[a] Margery Olivier was the oldest daughter of Sydney Olivier, 1st Baron Olivier, and his wife, Margaret Cox.[1] Sydney Olivier was a leading Fabian, Governor of Jamaica (1907–1913) and a minister in the Labour Government of Ramsay Macdonald in 1924 (Secretary for India).[2] He was one of ten children and among his brothers were Herbert Arnould Olivier, the artist, and Gerard, father of the actor Laurence Olivier. His sisters included the author, Edith Olivier.[3] Margaret Cox was one of nine children of Judge Homersham Cox. One of Margaret Cox's brothers was Harold Cox the Liberal Member of Parliament, another, the mathematician Homersham Cox. Of her sisters, Agatha Cox married the sculptor Sir William Hamo Thornycroft, while Ethel Cox married Captain Alfred Carpenter, the brother of Edward Carpenter the philosopher.[4]

The Oliviers were one of the founders of what came to be known as the "aristocracy of the left", a group associated with the rise of the women's movement, socialism and the Fabian Society. This group included the author, Edith Nesbit, the Webbs and the Shaws, and had close ties to William Morris and Edward Carpenter. These families, in turn raised a generation of progressive children, such as the Oliviers and the Reeves, whose daughter Amber, the Olivier daughters would encounter at Cambridge.[5] The Shaws, who were childless, saw the Olivier girls as surrogate daughters, and the characters of George Bernard Shaw's Heartbreak House were loosely based on the Oliviers and their "siren" daughters.[6]

Childhood (1887–1907) edit

The Oliviers had four children:

- Margery Olivier (1886-1974)

- Brynhild Olivier (1887–1935)

- Daphne (1889-1950)

- Noël (1892-1969)

Margery was born in London in 1886. Sydney Olivier was a career civil servant in the Colonial Office. In October 1890, when Margery was four, Olivier received his first posting overseas, leaving his family behind in London. He served for six months as Colonial Secretary (chief administrator) in British Honduras.[3] On his return, the Olivier family were ready for a move from London, and Margaret Olivier had been inspired by Edward Carpenter's Simple Life. They settled near Limpsfield Chart, Surrey, purchasing a cottage which they had previously used as a holiday retreat, converting it into a home, which they named "The Champions".[7] It lay at the foot of the North Downs, overlooking the Weald, and was backed by the dense Chart woods.

Like the other children in the community, the three older girls, Margery, Bryn and Daphne were all home schooled. They were also tutored for nine months in Lausanne to ensure competency in French.[8] Later, the progressive coeducational boarding school, Bedales, in Sussex, became available for the youngest sister, Noël.[2] Soon, like minded people started to settle in the neighbourhood. Among the first were the Peases and the Garnetts, Edward and Constance Garnett and their son, David “Bunny” Garnett. Others included Octavia Hill, the economist J. A. Hobson, the writers E. V. Lucas and Henry Salt and William and Margaret Pye, whose children included Edith, Ethel, Sybil and David. Ford Madox Ford lived there for a while and Margaret Olivier's sister Agatha and her family also moved to Surrey. Eventually the area became a hub of progressive Fabian intellectuals.[9][10][11] There, the four Olivier sisters led a free-spirited outdoor life, disdainful of social convention, which later made them very much aligned to the ethos of Rupert Brooke's Neo-pagans, building tree houses, referring to themselves as the Reivilo[b] tribe, and becoming very athletic in a manner that David Garnett compared to ancient Sparta. He also described them both as "ruthless Valkyries"[12] and as "cruel as savages".[c][15][16] One woman, hired as a nursemaid to care for the children in 1892 was the future author Gertrude Dix, herself an emancipated woman who described her child rearing philosophy as "principles of freedom", allowing children to learn through experience rather than rules.[17] Dix was a New Woman writer, and this philosophy permeated the culture of Limpsfield.[18] Among other early childhood influences, were G. B. Shaw and H. G. Wells.[19]

Sydney Olivier's duties in the Caribbean would continue to take him away from home.[20][2] Following his appointment as Colonial Administrator of Jamaica (1899–1904) he decided to summon the family to join him there in 1900, for the remainder of his term.[21] In 1907, Sir Sydney Olivier, as he had now become, left with Lady Margaret Olivier to take up the governorship of Jamaica, a position he maintained till 1913.[2] Margery, now 21 was put in charge of bringing up her three younger sisters. For the next few years the sisters' lives were divided between England and Jamaica, keeping their mother company and performing official functions at Government House.[5]

All four daughters (and their parents) were considered striking in their appearance.[6][22] They had also developed a reputation for unconventionality that would later come to the attention of Rupert Brooke's very protective mother, when it was reported to her: "The Oliviers! They'd do anything, those girls!".[2] Their reputation would also lead D. H. Lawrence to warn David Garnett they were "unclean".[23]

Education edit

Margery went up to Newnham College, Cambridge to read economics (1907–1911) and got a third in her tripos.[24]There, she was an important in the Cambridge Fabian Society, where she came into close contact with Rupert Brooke, a classics student at King's , who was a member of the steering committee of the Fabian Society and then President (1909–1910). Brooke had formed an interest in all four Olivier sisters, principally Noël, but used his association with Margery in the Fabian Society to pursue the others.[6]

Around July 1908 the loose association of friends, later dubbed Neo-pagans by the Stephen sisters, began to form around Brooke. The core group or inner circle being the four Olivier sisters, Justin Brooke, Jacques Raverat, Gwen and Frances Darwin and Ka Cox. The fringe members or outer circle included David Garnett, Geoffrey Keynes, Ethel and Sybil Pye, Dudley Ward, Godwin Baynes, and Ferenc Békássy.[25] Later it would include A. E. H. (Hugh) Popham (1889–1970),[26][27] a Cambridge diving champion who Bryn would later marry,[d] and Bryn's maternal cousin, Rosalind Thornycroft.[e][30] Following her economics studies, Margery decided to follow her younger sister Noël's example and enrolled in medical school in London.

By 1916 her friends and family were beginning to notice behavior that they described as "delusional insanity". In particular she became firmly convinced that a number of people were in love with her. In 1917 they persuaded her to see a psychiatrist who diagnosed "dementia", and a nurse was engaged for her care. The family struggled with the need to institutionalise her. Eventually her constant escapes from the house led to her being admitted to the Chiswick House asylum in April 1917, but she succeeded in escaping even from there. On her escape she made her way to Brynhild's house in Bloomsbury, and the latter realised she was now going to have to take care of her older sister as well.[31] The Oliviers and their friends were disillusioned about the level of care for mental illness, especially after the recent breakdowns of Daphne Olivier and Virginia Woolf, and struggled to keep Margery out of the hands of organised medicine.[32]

In October 1917, Bryn became convinced that it was in Margery's interests to be out of London. The Oliviers knew of an Irish doctor, Dr Caesar Sherrard, who had a farm at Tatsfield, Surrey, where he cared for soldiers affected by shell shock by having them work the land. Tatsfield, a village on the North Downs, overlooked Limpsfield, about four miles from the Olivier country home, The Champions. With great difficulty Bryn persuaded her sister to join her there, where they took a cottage on the farm and joined the workforce.[33] It was there that the sisters met the doctor's colourful young nephew, Raymond Sherrard (1893–1974),[f][34] another Cambridge graduate. Sherrard was a second lieutenant in the Essex Regiment, recovering from a motorcycle accident that kept him from the front. Despite Bryn's best efforts, Margery soon transferred her fixation to Raymond Sherrard, and she asked him to stay away.[34] Dr Sherrard died in 1920, and the family continued to seek solutions, hoping for a cure, in particular looking for a psychoanalytic approach, in contrast to the draconian conditions of contemporary asyla. They attempted to obtain consultations with Carl Jung, Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham, but to avail. Margery was having to progressively move from nursing home to nursing home, usually ending up in eviction.

Engagement

Notes edit

- ^ An honorific style of the daughters and sons of a baron

- ^ Reivilo - Olivier spelled backwards

- ^ Hence the original title of Sarah Watling's biography of the sisters, Noble Savages[13] eventually published as The Olivier Sisters. A Biography[14]

- ^ Hugh Popham was one of Brooke's friends at King's

- ^ Rosalind Thorneycroft (1891–1973) was the daughter of Agatha Cox and Sir William Hamo Thornycroft[28] Rosalind was the inspiration for D H Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover, as her mother had inspired Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles[29]

- ^ Francis Raymond George Nason Sherrard

References edit

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lundy475902was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

Innes185was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Mariz 2004.

- ^ Starr 2003, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Delany 1987, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

Innes186was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Watling 2019, p. 15.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. 20.

- ^ Withers 2016.

- ^ Rowbotham 2016, p. 78.

- ^ Watling 2019, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Cowdrey 2017.

- ^ Watling 2019.

- ^ Delany 1987, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Fowler27was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rowbotham 2016.

- ^ Watling 2019, pp. 9,23.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. xii.

- ^ Watling 2019, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. 55.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. ix.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. 147.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Marshall174was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Delany 1987, p. 41.

- ^ Delany 1987, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Janus 2008.

- ^ Victorian Artists 2018.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Jansen28was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Delany 1987, p. 88.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. 170.

- ^ Watling 2019, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Watling 2019, p. 173.

- ^ a b Watling 2019, p. 178.

External links edit