The urethra (pl.: urethras or urethrae) is a tube that connects the mammalian urinary bladder to the urinary meatus. Male and female placental mammals release urine through the urethra during urination, but males also release semen through the urethra during ejaculation.[1]

| Urethra | |

|---|---|

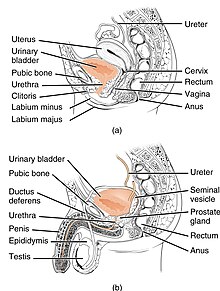

The urethra transports urine from the bladder to the outside of the body. This image shows (a) a human female urethra and (b) a human male urethra. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus |

| Artery | Inferior vesical artery Middle rectal artery Internal pudendal artery |

| Vein | Inferior vesical vein Middle rectal vein Internal pudendal vein |

| Nerve | Pudendal nerve Pelvic splanchnic nerves Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | Internal iliac lymph nodes Deep inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | urethra feminina (female); urethra masculina (male) |

| Greek | οὐρήθρα |

| MeSH | D014521 |

| TA98 | A08.4.01.001F A08.5.01.001M |

| TA2 | 3426, 3442 |

| FMA | 19667 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The external urethral sphincter is a striated muscle that allows voluntary control over urination.[2] The internal sphincter, formed by the involuntary smooth muscles lining the bladder neck and urethra, receives its nerve supply by the sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system.[3] The internal sphincter is present both in males and females.[4][5][6]

Structure edit

The urethra is a fibrous and muscular tube which connects the urinary bladder to the external urethral meatus. Its length differs between the sexes, because it passes through the penis in males.

Male edit

In the human male, the urethra is on average 18 to 20 centimeters (7.1 to 7.9 inches) long and opens at the end of the external urethral meatus.[7]

The urethra is divided into four parts in men, named after the location:[7]

| Region | Description | Epithelium |

| pre-prostatic urethra | This is the intramural part of the urethra surrounded by the internal urethral sphincter and varies between 0.5 and 1.5 cm in length depending on the fullness of the bladder. | Transitional |

| prostatic urethra | Crosses through the prostate gland. There are several openings at the posterior wall : (1) the ejaculatory duct (2 lateral) receives sperm from the vas deferens and ejaculate fluid from the seminal vesicle, (2) prostatic sinus which has openings for several prostatic ducts where fluid from the prostate enters and contributes to the ejaculate, (3) the prostatic utricle, which is merely an indentation. These openings are collectively called the verumontanum (colliculus seminalis)

The prostatic urethra is a common site of obstruction to outflow of urine in BPH patients |

Transitional |

| membranous urethra | A small (1 or 2 cm) portion passing through the external urethral sphincter. This is the narrowest part of the urethra. It is located in the deep perineal pouch. The bulbourethral glands (Cowper's gland) are found posterior to this region but open in the spongy urethra. | Pseudostratified columnar |

| spongy urethra (or penile urethra) | Runs along the length of the penis on its ventral (underneath) surface. It is about 15 to 25 cm in length,[8] and travels through the corpus spongiosum. The ducts from the urethral gland (gland of Littré) enter here. The openings of the bulbourethral glands are also found here.[9] Some textbooks will subdivide the spongy urethra into two parts, the bulbous and pendulous urethra. The urethral lumen runs effectively parallel to the penis, except at the narrowest point, the external urethral meatus, where it is vertical. This produces a spiral stream of urine and has the effect of cleaning the external urethral meatus. The lack of an equivalent mechanism in the female urethra partly explains why urinary tract infections occur so much more frequently in females. | Pseudostratified columnar – proximally, Stratified squamous – distally |

There is inadequate data for the typical length of the male urethra; however, a study of 109 men showed an average length of 22.3 cm (SD = 2.4 cm), ranging from 15 cm to 29 cm.[10]

Female edit

In the human female, the urethra is about 4 cm long,[7] and exits the body between the clitoris and the vagina, extending from the internal to the external urethral orifice. The meatus is located below the clitoris. It is placed behind the symphysis pubis, embedded in the anterior wall of the vagina, and its direction is obliquely downward and forward; it is slightly curved with the concavity directed forward. The proximal two-thirds of the urethra is lined by transitional epithelial cells, while the distal third is lined by stratified squamous epithelial cells.[11]

Between the superior and inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm, the female urethra is surrounded by the urethral sphincter.

Microanatomy edit

The cells lining the urethra (the epithelium) start off as transitional cells as it exits the bladder, which are variable layers of flat to cuboidal cells that change shape depending on whether they are compressed by the contents of the urethra.[12] Further along the urethra there are pseudostratified columnar and stratified columnar epithelia.[12] The lining becomes multiple layers of flat cells near the end of the urethra, which is the same as the external skin around it.[12]

There are small mucus-secreting urethral glands, as well as bulbo-urethral glands of Cowper, that secrete mucous acting to lubricate the urethra.[12]

The urethra consists of three coats: muscular, erectile, and mucous, the muscular layer being a continuation of that of the bladder.

Blood and nerve supply and lymphatics edit

Somatic (conscious) innervation of the external urethral sphincter is supplied by the pudendal nerve.

Development edit

In the developing embryo, at the hind end lies a cloaca. This, over the fourth to the seventh week, divides into a urogenital sinus and the beginnings of the anal canal, with a wall forming between these two inpouchings called the urorectal septum.[13] The urogenital sinus divides into three parts, with the middle part forming the urethra; the upper part is largest and becomes the urinary bladder, and the lower part then changes depending on the biological sex of the embryo.[13] The cells lining the urethra (the epithelium) come from endoderm, whereas the connective tissue and smooth muscle parts are derived from mesoderm.[13]

After the third month, urethra also contributes to the development of associated structures depending on the biological sex of the embryo. In the male, the epithelium multiples to form the prostate. In the female, the upper part of the urethra forms the urethra and paraurethral glands.[13]

Function edit

Urination edit

The urethra is the vessel through which urine passes after leaving the bladder. During urination, the smooth muscle lining the urethra relaxes in concert with bladder contraction(s) to forcefully expel the urine in a pressurized stream. Following this, the urethra re-establishes muscle tone by contracting the smooth muscle layer, and the bladder returns to a relaxed, quiescent state. Urethral smooth muscle cells are mechanically coupled to each other to coordinate mechanical force and electrical signaling in an organized, unitary fashion.[14]

Ejaculation edit

The male urethra is the conduit for semen during orgasm.[1] Urine is removed before ejaculation by pre-ejaculate fluid – called Cowper's fluid – from the bulbourethral gland.[15][16]

Clinical significance edit

Infection of the urethra is urethritis, which often causes purulent urethral discharge.[17] It is most often due to a sexually transmitted infection such as gonorrhoea or chlamydia, and less commonly due to other bacteria such as ureaplasma or mycoplasma; trichomonas vaginalis; or the viruses herpes simplex virus and adenovirus.[17] Investigations such as a gram stain of the discharge might reveal the cause; nucleic acid testing based on the first urine sample passed in a day, or a swab of the urethra sent for bacterial culture and sensitivity may also be used.[17] Treatment usually involves antibiotics that treat both gonorrhoea and chlamydia, as these often occur together.[17] A person being treated for urethritis should not have sex until the infection is treated, so that they do not spread the infection to others.[17] Because of this spread, which may occur during an incubation period before a person gets symptoms, there is often contact tracing so that sexual partners of an affected person can be found and treatment offered.[17]

Cancer can also develop in the lining of the urethra.[18] When cancer is present, the most common symptom in an affected person is blood in the urine; a physical medical examination may be otherwise normal, except in late disease.[18] Cancer of the urethra is most often due to cancer of the cells lining the urethra, called transitional cell carcinoma, although it can more rarely occur as a squamous cell carcinoma if the type of cells lining the urethra have changed, such as due to a chronic schistosomiasis infection.[18] Investigations performed usually include collecting a sample of urine for an inspection for malignant cells under a microscope, called cytology, as well as examination with a flexible camera through the urethra, called urethroscopy. If a malignancy is found, a biopsy will be taken, and a CT scan will be performed of other body parts (a CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis) to look for additional metastatic lesions.[18] After the cancer is staged, treatment may involve chemotherapy.[citation needed]

Injury edit

Passage of kidney stones through the urethra can be painful. Damage to the urethra, such as by kidney stones, chronic infection, cancer, or from catheterisation, can lead to narrowing, called a urethral stricture.[19] The location and structure of the narrowing can be investigated with a medical imaging scan in which dye is injected through the urinary meatus into the urethra, called a retrograde urethrogram.[20] Additional forms of imaging, such as ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging may also be used to provide further details.[20]

Injuries to the urethra (e.g., from a pelvic fracture[21])

Foreign bodies in the urethra are uncommon, but there have been medical case reports of self-inflicted injuries, a result of insertion of foreign bodies into the urethra such as an electrical wire.[22]

Other edit

Hypospadias and epispadias are forms of abnormal development of the urethra in the male, where the meatus is not located at the distal end of the penis (it occurs lower than normal with hypospadias, and higher with epispadias). In a severe chordee, the urethra can develop between the penis and the scrotum.

Catheterisation edit

A tube called a catheter can be inserted through the urethra to drain urine from the bladder, called an indwelling urinary catheter; or, to bypass the urethra, a catheter may be directly inserted through the abdominal wall into the bladder, called a suprapubic catheter.[23] This may be to relieve or bypass an obstruction, to monitor how much urine someone produces, or because a person has difficulty urinating, for example due to a neurological cause such as multiple sclerosis.[23] Complications that are associated with catheter insertion can include catheter-associated infections, injury to the urethra or nearby structures, or pain.[23]

Other animals edit

In all mammals, with the exception of monotremes, and in both sexes, the urethra serves primarily to drain and excrete urine, which in mammals, collects in the urinary bladder and is released from there into the urethra. In addition, the closing mechanisms of the urethra, together with immunoglobulins, largely prevent germs from penetrating the inside of the body.[24] In marsupials, the female's urethra empties into the urogenital sinus.[25]

History edit

The word "urethra" comes from the Ancient Greek οὐρήθρα – ourḗthrā. The stem "uro" relating to urination, with the structure described as early as the time of Hippocrates.[26] Confusingly however, at the time it was called "ureter". Thereafter, terms "ureter" and "urethra" were variably used to refer to each other thereafter for more than a millennia.[26] It was only in the 1550s that anatomists such as Bartolomeo Eustacchio and Jacques Dubois began to use the terms to specifically and consistently refer to what is in modern English called the ureter and the urethra.[26] Following this, in the 19th and 20th centuries, multiple terms relating to the structures such as urethritis and urethrography, were coined.[26]

Kidney stones have been identified and recorded about as long as written historical records exist.[27] The urinary tract as well as its function to drain urine from the kidneys, has been described by Galen in the second century AD.[28] Surgery to the urethra to remove kidney stones has been described since at least the first century AD by Aulus Cornelius Celsus.[28]

Additional images edit

-

Position of the urethra in males

-

Transverse section of the penis

-

Male urethral opening on glans penis

-

Female urethral opening within vulval vestibule

-

Muscles of the female perineum

-

Urethra. Deep dissection. Serial cross section.

-

Diagram which depicts the membranous urethra and the spongy urethra of a male

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b Marvalee H. Wake (15 September 1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. pp. 583–. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Legato, Marianne J.; Bilezikian, John P., eds. (2004). "109: The Evaluation and Treatment of Urinary Incontinence". Principles of Gender-specific Medicine. Vol. 1. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 1187.

- ^ Chancellor, Michael B; Yoshimura, Naoki (2004). "Neurophysiology of Stress Urinary Incontinence". Reviews in Urology. 6 (Suppl 3): S19–S28. PMC 1472861. PMID 16985861.

- ^ Jung, Junyang; Anh, Hyo Kwang; Huh, Youngbuhm (September 2012). "Clinical and Functional Anatomy of the Urethral Sphincter". International Neurourology Journal. 16 (3): 102–106. doi:10.5213/inj.2012.16.3.102. PMC 3469827. PMID 23094214.

- ^ Karam, I.; Moudouni, S.; Droupy, S.; Abd-Almasad, I.; Uhl, J. F.; Delmas, V. (April 2005). "The structure and innervation of the male urethra: histological and immunohistochemical studies with three-dimensional reconstruction". Journal of Anatomy. 206 (4): 395–403. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00402.x. PMC 1571491. PMID 15817107.

- ^ Ashton-Miller, J. A.; DeLancey, J. O. (April 2007). "Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1101 (1): 266–296. Bibcode:2007NYASA1101..266A. doi:10.1196/annals.1389.034. hdl:2027.42/72597. PMID 17416924. S2CID 6310287. Archived from the original on Aug 22, 2023 – via Deep Blue Documents.

- ^ a b c Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). "Bladder, prostate and urethra". Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited. pp. 1261–1266. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- ^ "Male Urethra Function & Urethra Anatomy Pictures". Center For Reconstructive Urology. Archived from the original on Sep 26, 2023.

- ^ Atlas of Human Anatomy 5th Edition, Netter.

- ^ Kohler TS, Yadven M, Manvar A, Liu N, Monga M (2008). "The length of the male urethra". International Brazilian Journal of Urology. 34 (4): 451–4, discussion 455–6. doi:10.1590/s1677-55382008000400007. PMID 18778496.

- ^ Manual of Obstetrics. (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1-16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ^ a b c d Young, Barbara; O'Dowd, Geraldine; Woodford, Phillip (2013). "Male reproductive system". Wheater's functional histology: a text and colour atlas (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 349. ISBN 9780702047473.

- ^ a b c d Sadley, TW (2019). "Bladder and urethra". Langman's medical embryology (14th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 263–66. ISBN 9781496383907.

- ^ Kyle BD (Aug 2014). "Ion Channels of the Mammalian Urethra". Channels. 8 (5): 393–401. doi:10.4161/19336950.2014.954224. PMC 4594508. PMID 25483582.

- ^ Killick, Stephen R.; Leary, Christine; Trussell, James; Guthrie, Katherine A. (15 December 2010). "Sperm content of pre-ejaculatory fluid". Human Fertility. 14 (1): 48–52. doi:10.3109/14647273.2010.520798. PMC 3564677. PMID 21155689.

- ^ Chughtai B, Sawas A, O'Malley RL, Naik RR, Ali Khan S, Pentyala S (April 2005). "A neglected gland: a review of Cowper's gland". Int. J. Androl. 28 (2): 74–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00499.x. PMID 15811067. S2CID 32553227.

- ^ a b c d e f Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P. (eds.) (2018). "Urethral discharge". Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

{{cite book}}:|first4=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d Ralston, Stuart H.; Penman, Ian D.; Strachan, Mark W.; Hobson, Richard P. (eds.) (2018). "Urothelial tumours". Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (23rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 435–6. ISBN 978-0-7020-7028-0.

{{cite book}}:|first4=has generic name (help) - ^ "Urethral stricture". Mayo Clinic. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b Maciejewski, Conrad; Rourke, Keith (2015-12-02). "Imaging of urethral stricture disease". Translational Andrology and Urology. 4 (1): 2–9. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.02.03. ISSN 2223-4691. PMC 4708283. PMID 26816803.

- ^ Stein DM, Santucci RA (July 2015). "An update on urotrauma". Current Opinion in Urology. 25 (4): 323–30. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000184. PMID 26049876. S2CID 26994715.

- ^ Stravodimos, Konstantinos G; Koritsiadis, Georgios; Koutalellis, Georgios (2009). "Electrical wire as a foreign body in a male urethra: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 3: 49. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-3-49. PMC 2649937. PMID 19192284.

- ^ a b c "Urinary catheters - NHS". nhs.uk. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Michaeltitle=Microbial Inhabitants of Humans: Their Ecology and Role in Health and Disease (2005). Microbial Inhabitants of Humans: Their Ecology and Role in Health and Disease. Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-521-84158-0.

- ^ Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe; Marilyn Renfree (30 January 1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. pp. 172–. ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- ^ a b c d Marx, Franz Josef; Karenberg, Axel (2010). "Uro-words making history: Ureter and urethra". The Prostate. 70 (9): 952–958. doi:10.1002/pros.21129. PMID 20166127. S2CID 32778667.

- ^ Tefekli, Ahmet; Cezayirli, Fatin (2013). "The History of Urinary Stones: In Parallel with Civilization". The Scientific World Journal. 2013: 423964. doi:10.1155/2013/423964. PMC 3856162. PMID 24348156.

- ^ a b Nahon, Irmina; Waddington, Gordon; Dorey, Grace; Adams, Roger (2011). "The History of Urologic Surgery: From Reeds to Robotics". Urologic Nursing. 31 (3): 173–180. doi:10.7257/1053-816X.2011.31.3.173. PMID 21805756.

External links edit

- Histology at KUMC epithel-epith07 "Male Urethra"