This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2016) |

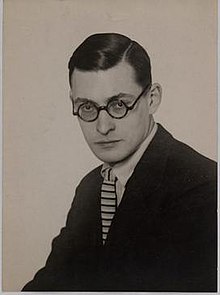

Raymond Queneau (French: [ʁɛmɔ̃ kəno]; 21 February 1903 – 25 October 1976) was a French novelist, poet, critic, editor[1] and co-founder and president of Oulipo[2] (Ouvroir de littérature potentielle), notable for his wit and cynical humour.

Raymond Queneau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 February 1903 Le Havre, France |

| Died | 25 October 1976 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Novelist, Poet |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | University of Paris |

| Spouse | Janine Kahn |

| Signature | |

| |

Biography

editQueneau was born at 47, rue Thiers (now Avenue René-Coty), Le Havre, Seine-Inférieure,[1] the only child of Auguste Queneau and Joséphine Mignot. After studying in Le Havre, Queneau moved to Paris in 1920 and received his first baccalauréat in 1925 for philosophy from the University of Paris.[1] Queneau performed military service as a zouave in Algeria and Morocco during the years 1925–26.[3] During the 1920s and 1930s Queneau took odd jobs for income such as bank teller, tutor, translator and some writing in a column entitled, "Connaissez-vous Paris?" for the daily Intransigeant.[1]

He married Janine Kahn (1903–1972) in 1928 after returning to Paris from his first military service.[1][4] Kahn was the sister-in-law of André Breton, leader of the surrealist movement.[1] In 1934 they had a son, Jean-Marie, who became a painter.[5]

Queneau was drafted in August 1939 and served in small provincial towns before his promotion to corporal just before being demobilized in 1940.[1] After a prolific career of writing, editing and critique, Queneau died on 25 October 1976.[3] He is buried with his parents in the old cemetery of Juvisy-sur-Orge, in Essonne outside Paris.

Career

editQueneau spent much of his life working for the Gallimard publishing house, where he began as a reader in 1938. He later rose to be general secretary and eventually became director of l'Encyclopédie de la Pléiade in 1956. During some of this time, he also taught at l'École Nouvelle de Neuilly. He entered the Collège de 'Pataphysique in 1950, where he became Satrap.

In 1950, Juliette Gréco recorded "Si tu t'imagines", a song by Joseph Kosma with lyrics by Queneau.

During this time, Queneau also acted as a translator, notably for Amos Tutuola's The Palm-Wine Drinkard (L'Ivrogne dans la brousse) in 1953. Additionally, he edited and published Alexandre Kojève's lectures on Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. Queneau had been a student of Kojève during the 1930s and was, during this period, also close to writer Georges Bataille.

As an author, Queneau came to general attention in France with the publication in 1959 of his novel Zazie dans le métro.[1] In 1960 the film adaptation directed by Louis Malle was released during the Nouvelle Vague movement. Zazie explores colloquial language as opposed to "standard" written French. The first word of the book, the alarmingly long "Doukipudonktan" is a playful phonetic transcription of "D'où qu'il pue / qu'ils puent donc tant?" – "Why does it / does he / do they stink so much?"

Before he founded the Ouvroir de littérature potentielle (Oulipo) in 1960,[2] Queneau was attracted to mathematics as a source of inspiration. He became a member of la Société Mathématique de France in 1948. In Queneau's mind, elements of a text, including seemingly trivial details such as the number of chapters, were things that had to be predetermined, perhaps calculated. This was an issue during the writing of A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, also known as 100,000,000,000,000 Poems.[2] Queneau wrote 140 lines in 10 individual sonnets that could all be taken apart and rearranged in any order. Queneau calculated that anyone reading the book 24 hours a day would need 190,258,751 years to finish it.[2] While Queneau was completing this work, he asked mathematician François Le Lionnais for help with issues he was having, and their conversation led to a role of mathematics in literature, which led to the creation of the Oulipo.[2] His work encouraged Jacques Lacan to pursue his pioneering work on game theory and the use of mathematics in psychoanalysis.[6]

A later work, Les fondements de la littérature d'après David Hilbert (1976), alludes to the mathematician David Hilbert, and attempts to explore the foundations of literature by quasi-mathematical derivations from textual axioms. Queneau claimed this final work would prove "a hidden master of the automaton." Pressed by GF, his interlocutor, Queneau confided that the text "could never appear, but had to hide to glorify that without agency."

One of Queneau's most influential works is Exercises in Style, which tells the simple story of a man's seeing the same stranger twice in one day. It tells that short story in 99 different ways, demonstrating the tremendous variety of styles in which storytelling can take place. An excerpt from this piece was published in 0 to 9 magazine, a 1960s publication which experimented with language and meaning-making.

The works of Raymond Queneau are published by Gallimard in the collection Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

Queneau and Surrealists

editIn 1924 Queneau met and briefly joined the Surrealists, but never fully shared their penchants for automatic writing or ultra-left politics. Like many surrealists, he entered psychoanalysis—however, not in order to stimulate his creative abilities, but for personal reasons, as with Leiris, Bataille, and Crevel.[citation needed]

Michel Leiris describes, in Brisees, how he first met Queneau in 1924, while vacationing in Nemours with André Masson, Armand Salacrou and Juan Gris. A common friend, Roland Tual, met Queneau on a train from Le Havre and brought him over. Queneau was a few years younger and felt less accomplished than the other men. He did not make a big impression on the young bohemians. After Queneau came back from the army, around 1926–7, he and Leiris met at the Café Certa, near L'Opera, a Surrealist hang-out. On this occasion, when conversation delved into Eastern philosophy, Queneau's comments showed a quiet superiority and erudite thoughtfulness. Leiris and Queneau became friends later while writing for Bataille's Documents.[citation needed]

Queneau questioned Surrealist support of the USSR in 1926. He remained on cordial terms with André Breton,[3] although he also continued associating with Simone Kahn after Breton split up with her. Breton usually demanded that his followers ostracize his former girlfriends. It would have been difficult for Queneau to avoid Simone, however, since he married her sister, Janine, in 1928.[1] The year that Breton left Simone, she sometimes traveled around France with her sister and Queneau.[citation needed]

By 1930, Queneau separated himself significantly from Breton and the Surrealists.[1] Eluard, Aragon and Breton had joined the French Communist party in 1927; Queneau did not, and instead participated in Un Cadavre (A Corpse, 1930), a vehemently anti-Breton pamphlet co-written by Bataille, Leiris, Prévert, Alejo Carpentier, Jacques Baron, J.-A. Boiffard, Robert Desnos, Georges Limbour, Max Morise, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Roger Vitrac.[citation needed]

Queneau also joined the Democratic Communist Circle founded by Boris Souvarine and took up numerous left-wing and anti-fascist causes.[7] He defended the Popular Front in France and the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.[7] Under the Nazi occupation of France, he published in many left-wing journals associated with the Resistance. After World War II, Queneau continued to lend his support left-wing manifestos and petitions, and condemned McCarthyism and anti-communist persecution in Greece.[7]

He wrote more scientific than literary reviews: on Pavlov, Vernadsky (from whom he got a circular theory of sciences), and a review of a book on the history of equestrian caparisons by an artillery officer. He also helped with writing passages on Engels and a mathematical dialectic for Bataille's article, "A critique of the foundations of Hegelian dialectic."[citation needed]

Jacques Lacan became seriously interested in mathematics, and made early contributions to game theory, after reading Queneau's works.[8]

Legacy and honors

edit- 1951, elected to the Académie Goncourt

- 1952, elected to the Académie de l'humour

- 1955–57, invited to jury of the Cannes Film Festival

Bibliography

editNovels

edit- Le Chiendent (1933). The Bark-Tree, trans. Barbara Wright (Calder & Boyars, 1968); later published as Witch Grass (New York Review Books, 2003; ISBN 1-59017-031-8)

- Gueule de pierre (1934). Gob of Stone

- Les Derniers Jours (1936). The Last Days, trans. Barbara Wright (Dalkey Archive, 1990; ISBN 1-56478-140-2)

- Odile (1937). Trans. Carol Sanders (Dalkey Archive, 1988; ISBN 0-916583-34-1)

- Les Enfants du Limon (1938). Children of Clay, trans. Madeleine Velguth (Sun & Moon, 1998; ISBN 1-55713-272-0)

- Un rude hiver (1939). A Hard Winter, trans. Betty Askwith (J. Lehmann, 1948)

- Les Temps mêlés (Gueule de Pierre II) (1941)

- Pierrot mon ami (1942). Pierrot, trans. Julian Maclaren-Ross (J. Lehmann, 1950) and Barbara Wright (Dalkey Archive, 1987; ISBN 1-56478-397-9)

- Loin de Rueil (1944). The Skin of Dreams, trans. H.J. Kaplan (New Directions, 1948; ISBN 0-947757-16-3) and Chris Clarke (New York Review Books, 2024; ISBN 9781681377704)

- On est toujours trop bon avec les femmes (1947). We Always Treat Women Too Well, trans. Barbara Wright (J. Calder, 1981; ISBN 1-59017-030-X)

- Saint-Glinglin (1948). Trans. James Sallis (Dalkey Archive, 1993; ISBN 1-56478027-9)

- Le Journal intime de Sally Mara (1950)

- Le Dimanche de la vie (1952). The Sunday of Life, trans. Barbara Wright (J. Calder, 1976; ISBN 0-8112-0646-7)

- Zazie dans le métro (1959). Zazie in the Metro, trans. Barbara Wright (Harper, 1960; ISBN 0-14-218004-1)

- Les Fleurs bleues (1965). The Blue Flowers, trans. Barbara Wright (Atheneum, 1967; ISBN 0-8112-0945-8); also published as Between Blue and Blue (The Bodley Head, 1967)

- Le Vol d'Icare (1968). The Flight of Icarus, trans. Barbara Wright (Calder & Boyars, 1973; ISBN 0-8112-0483-9)

Poetry

edit- Chêne et chien (1937). Trans. Madeleine Velguth (P. Lang, 1995; ISBN 0-8204-2311-4)

- Les Ziaux (1943)

- L'Instant fatal (1946)

- Petite cosmogonie portative (1950)

- Cent Mille Milliards de Poèmes (1961). Hundred Thousand Billion Poems

- Le chien à la mandoline (1965)

- Battre la campagne (1967). Beating the Bushes

- Courir les rues (1967). Hitting the Streets, trans. Rachel Galvin (Carcanet, 2013)

- Fendre les flots (1969)

- Morale élémentaire (1975). Elementary Morality

Essays and articles

edit- Joan Miró; ou, Le poète préhistorique (1949)

- Bâtons, chiffres et lettres (1950)

- Pour une bibliothèque idéale or For an Ars Poetica (1956)

- Entretiens avec Georges Charbonnier (1962)

- Bords (1963)

- Une Histoire modèle (1966)

- Le Voyage en Grèce (1973)

- Traité des vertus démocratiques (1955)

Other

edit- Un Cadavre (1930) with Jacques Baron, Georges Bataille, J.-A. Boiffard, Robert Desnos, Michel Leiris, Georges Limbour, Max Morise, Jacques Prévert, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Roger Vitrac.

- En passant (1944) – theatre.

- Exercices de style (1947). Exercises in Style, trans. Barbara Wright (Gaberbocchus Press, 1958; ISBN 0-7145-4238-5)

- La Mort en ce Jardin (1956). Death in the Garden – with Luis Buñuel, screenplay for the Franco-Mexican film production.

- Les fondements de la littérature d'après David Hilbert (1976)

- Contes et propos (1981) – a collection of short tales or sketches.

- Journal 1939–1940 (1986)

- Journaux 1914–1965 (1996)

Compilations in English

edit- The Trojan Horse & At the Edge of the Forest (Gaberbocchus Press, 1954). Trans. Barbara Wright.

- Pounding the Pavements, Beating the Bushes, and Other Pataphysical Poems (Unicorn Press, 1985). Trans. Teo Savory. ISBN 0-87775-172-2

- Five Stories (Obscure Publications, 2000). Trans. Barbara Wright. Compiles: "Panic"; "Dino"; "At the Edge of the Forest"; "A Blue Funk"; and "The Trojan Horse"

- Stories & Remarks (University of Nebraska Press, 2000). Trans. Marc Lowenthal.

- Letters, Numbers, Forms: Essays, 1928-70 (University of Illinois Press, 2007). Trans. Jordan Stump.

- EyeSeas: Selected Poems (Black Widow Press, 2008). Trans. Daniela Hurezanu and Stephen Kessler.

In other art

edit- Zazie dans le métro (1960), released as film adaptation

- Pierre Bastien[9] has made a CD with the bilingual pun title Eggs Air Sister Steel, based on Exercices de Style (which "Eggs Air Sister Steel" sounds like when spoken).

- A typographic interpretation of the German version of Exercices de Style, "Stilübungen – visuelle Interpretationen" by the graphic designer Marcus Kraft, was published in 2006.

- Spanish-Canadian composer José Evangelista wrote the song cycle "Exercises de style" setting texts from Queneau's titular book in 1997.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Magill, Frank (1997). Cyclopedia of World Authors. California: Salem Press. p. 1660.

- ^ a b c d e Mathews, Harry (1998). Oulipo Compedium. London: Atlas Press. p. 14. ISBN 1-900565-18-8.

- ^ a b c Thiher, Allen (1985). Raymond Queneau. Boston: Twayne Publisher. pp. 2. ISBN 9780805766134.

- ^ "Janine Queneau (1903-1972)". data.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Magill, Frank Northen (1989). Cyclopedia of World Authors II. Salem Press. ISBN 978-0-89356-516-9.

- ^ "The Number Thirteen and the Logical Form of Suspicion"

- ^ a b c Galvin, Rachel (2017). News of War: Civilian Poetry 1936–1945. Oxford University Press. pp. 209–210.

- ^ Pierre Courtois, Tarik Tazdaït. Jacques Lacan and game theory: an early contribution to common knowledge reasoning. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 2021, 28 (5), pp.844-869. ff10.1080/09672567.2021.1908392ff. ffhal-03179414f

- ^ "Discography". Pierrebastien.com. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

Further reading

edit- Raymond Queneau by Richard Cobb (Clarendon, 1976)

External links

edit- www.queneau.net at the Wayback Machine (archived 11 June 2008) Queneau's former website

- Periodicals, Gallimard

- Article

- Université McGill: le roman selon les romanciers (French) Inventory and analysis of Raymond Queneau's essays writings about the novel

- Letterism papers, 1946–1965. Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California

- Raymond Queneau at IMDb