Pyruvate kinase is the enzyme involved in the last step of glycolysis. It catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to adenosine diphosphate (ADP), yielding one molecule of pyruvate and one molecule of ATP.[1] Pyruvate kinase was inappropriately named (inconsistently with a conventional kinase) before it was recognized that it did not directly catalyze phosphorylation of pyruvate, which does not occur under physiological conditions.[2] Pyruvate kinase is present in four distinct, tissue-specific isozymes in animals, each consisting of particular kinetic properties necessary to accommodate the variations in metabolic requirements of diverse tissues.

| Pyruvate kinase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

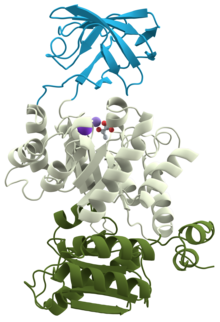

3D structure of pyruvate kinase (1PKN) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 2.7.1.40 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9001-59-6 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Isozymes in vertebrates edit

Four isozymes of pyruvate kinase expressed in vertebrates: L (liver), R (erythrocytes), M1 (muscle and brain) and M2 (early fetal tissue and most adult tissues). The L and R isozymes are expressed by the gene PKLR, whereas the M1 and M2 isozymes are expressed by the gene PKM2. The R and L isozymes differ from M1 and M2 in that they are allosterically regulated. Kinetically, the R and L isozymes of pyruvate kinase have two distinct conformation states; one with a high substrate affinity and one with a low substrate affinity. The R-state, characterized by high substrate affinity, serves as the activated form of pyruvate kinase and is stabilized by PEP and fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), promoting the glycolytic pathway. The T-state, characterized by low substrate affinity, serves as the inactivated form of pyruvate kinase, bound and stabilized by ATP and alanine, causing phosphorylation of pyruvate kinase and the inhibition of glycolysis.[3] The M2 isozyme of pyruvate kinase can form tetramers or dimers. Tetramers have a high affinity for PEP, whereas, dimers have a low affinity for PEP. Enzymatic activity can be regulated by phosphorylating highly active tetramers of PKM2 into an inactive dimers.[4]

The PKM gene consists of 12 exons and 11 introns. PKM1 and PKM2 are different splicing products of the M-gene (PKM1 contains exon 9 while PKM2 contains exon 10) and solely differ in 23 amino acids within a 56-amino acid stretch (aa 378-434) at their carboxy terminus.[5][6] The PKM gene is regulated through heterogenous ribonucleotide proteins like hnRNPA1 and hnRNPA2.[7] Human PKM2 monomer has 531 amino acids and is a single chain divided into A, B and C domains. The difference in amino acid sequence between PKM1 and PKM2 allows PKM2 to be allosterically regulated by FBP and for it to form dimers and tetramers while PKM1 can only form tetramers.[8]

Isozymes in bacteria edit

Many Enterobacteriaceae, including E. coli, have two isoforms of pyruvate kinase, PykA and PykF, which are 37% identical in E. coli (Uniprot: PykA, PykF). They catalyze the same reaction as in eukaryotes, namely the generation of ATP from ADP and PEP, the last step in glycolysis, a step that is irreversible under physiological conditions. PykF is allosterically regulated by FBP which reflects the central position of PykF in cellular metabolism.[9] PykF transcription in E. coli is regulated by the global transcriptional regulator, Cra (FruR).[10][11][12] PfkB was shown to be inhibited by MgATP at low concentrations of Fru-6P, and this regulation is important for gluconeogenesis.[13]

Reaction edit

Glycolysis edit

There are two steps in the pyruvate kinase reaction in glycolysis. First, PEP transfers a phosphate group to ADP, producing ATP and the enolate of pyruvate. Secondly, a proton must be added to the enolate of pyruvate to produce the functional form of pyruvate that the cell requires.[14] Because the substrate for pyruvate kinase is a simple phospho-sugar, and the product is an ATP, pyruvate kinase is a possible foundation enzyme for the evolution of the glycolysis cycle, and may be one of the most ancient enzymes in all earth-based life. Phosphoenolpyruvate may have been present abiotically, and has been shown to be produced in high yield in a primitive triose glycolysis pathway.[15]

In yeast cells, the interaction of yeast pyruvate kinase (YPK) with PEP and its allosteric effector Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP,) was found to be enhanced by the presence of Mg2+. Therefore, Mg2+ was concluded to be an important cofactor in the catalysis of PEP into pyruvate by pyruvate kinase. Furthermore, the metal ion Mn2+ was shown to have a similar, but stronger effect on YPK than Mg2+. The binding of metal ions to the metal binding sites on pyruvate kinase enhances the rate of this reaction.[16]

The reaction catalyzed by pyruvate kinase is the final step of glycolysis. It is one of three rate-limiting steps of this pathway. Rate-limiting steps are the slower, regulated steps of a pathway and thus determine the overall rate of the pathway. In glycolysis, the rate-limiting steps are coupled to either the hydrolysis of ATP or the phosphorylation of ADP, causing the pathway to be energetically favorable and essentially irreversible in cells. This final step is highly regulated and deliberately irreversible because pyruvate is a crucial intermediate building block for further metabolic pathways.[17] Once pyruvate is produced, it either enters the TCA cycle for further production of ATP under aerobic conditions, or is converted to lactic acid or ethanol under anaerobic conditions.

Gluconeogenesis: the reverse reaction edit

Pyruvate kinase also serves as a regulatory enzyme for gluconeogenesis, a biochemical pathway in which the liver generates glucose from pyruvate and other substrates. Gluconeogenesis utilizes noncarbohydrate sources to provide glucose to the brain and red blood cells in times of starvation when direct glucose reserves are exhausted.[17] During fasting state, pyruvate kinase is inhibited, thus preventing the "leak-down" of phosphoenolpyruvate from being converted into pyruvate;[17] instead, phosphoenolpyruvate is converted into glucose via a cascade of gluconeogenesis reactions. Although it utilizes similar enzymes, gluconeogenesis is not the reverse of glycolysis. It is instead a pathway that circumvents the irreversible steps of glycolysis. Furthermore, gluconeogenesis and glycolysis do not occur concurrently in the cell at any given moment as they are reciprocally regulated by cell signaling.[17] Once the gluconeogenesis pathway is complete, the glucose produced is expelled from the liver, providing energy for the vital tissues in the fasting state.

Regulation edit

Glycolysis is highly regulated at three of its catalytic steps: the phosphorylation of glucose by hexokinase, the phosphorylation of fructose-6-phosphate by phosphofructokinase, and the transfer of phosphate from PEP to ADP by pyruvate kinase. Under wild-type conditions, all three of these reactions are irreversible, have a large negative free energy and are responsible for the regulation of this pathway.[17] Pyruvate kinase activity is most broadly regulated by allosteric effectors, covalent modifiers and hormonal control. However, the most significant pyruvate kinase regulator is fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), which serves as an allosteric effector for the enzyme.

Allosteric effectors edit

Allosteric regulation is the binding of an effector to a site on the protein other than the active site, causing a conformational change and altering the activity of that given protein or enzyme. Pyruvate kinase has been found to be allosterically activated by FBP and allosterically inactivated by ATP and alanine.[18] Pyruvate Kinase tetramerization is promoted by FBP and Serine while tetramer dissociation is promoted by L-Cysteine.[19][20][21]

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate edit

FBP is the most significant source of regulation because it comes from within the glycolysis pathway. FBP is a glycolytic intermediate produced from the phosphorylation of fructose 6-phosphate. FBP binds to the allosteric binding site on domain C of pyruvate kinase and changes the conformation of the enzyme, causing the activation of pyruvate kinase activity.[22] As an intermediate present within the glycolytic pathway, FBP provides feedforward stimulation because the higher the concentration of FBP, the greater the allosteric activation and magnitude of pyruvate kinase activity. Pyruvate kinase is most sensitive to the effects of FBP. As a result, the remainder of the regulatory mechanisms serve as secondary modification.[9][23]

Covalent modifiers edit

Covalent modifiers serve as indirect regulators by controlling the phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, acetylation, succinylation and oxidation of enzymes, resulting in the activation and inhibition of enzymatic activity.[24] In the liver, glucagon and epinephrine activate protein kinase A, which serves as a covalent modifier by phosphorylating and deactivating pyruvate kinase. In contrast, the secretion of insulin in response to blood sugar elevation activates phosphoprotein phosphatase I, causing the dephosphorylation and activation of pyruvate kinase to increase glycolysis. The same covalent modification has the opposite effect on gluconeogenesis enzymes. This regulation system is responsible for the avoidance of a futile cycle through the prevention of simultaneous activation of pyruvate kinase and enzymes that catalyze gluconeogenesis.[25]

Hormonal control edit

In order to prevent a futile cycle, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis are heavily regulated in order to ensure that they are never operating in the cell at the same time. As a result, the inhibition of pyruvate kinase by glucagon, cyclic AMP and epinephrine, not only shuts down glycolysis, but also stimulates gluconeogenesis. Alternatively, insulin interferes with the effect of glucagon, cyclic AMP and epinephrine, causing pyruvate kinase to function normally and gluconeogenesis to be shut down. Furthermore, glucose was found to inhibit and disrupt gluconeogenesis, leaving pyruvate kinase activity and glycolysis unaffected. Overall, the interaction between hormones plays a key role in the functioning and regulation of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis in the cell.[26]

Inhibitory effect of metformin edit

Metformin, or dimethylbiguanide, is the primary treatment used for type 2 diabetes. Metformin has been shown to indirectly affect pyruvate kinase through the inhibition of gluconeogenesis. Specifically, the addition of metformin is linked to a marked decrease in glucose flux and increase in lactate/pyruvate flux from various metabolic pathways. Although metformin does not directly affect pyruvate kinase activity, it causes a decrease in the concentration of ATP. Due to the allosteric inhibitory effects of ATP on pyruvate kinase, a decrease in ATP results in diminished inhibition and the subsequent stimulation of pyruvate kinase. Consequently, the increase in pyruvate kinase activity directs metabolic flux through glycolysis rather than gluconeogenesis.[27]

Gene Regulation edit

Heterogenous ribonucleotide proteins (hnRNPs) can act on the PKM gene to regulate expression of M1 and M2 isoforms. PKM1 and PKM2 isoforms are splice variants of the PKM gene that differ by a single exon. Various types of hnRNPs such as hnRNPA1 and hnRNPA2 enter the nucleus during hypoxia conditions and modulate expression such that PKM2 is up-regulated.[28] Hormones such as insulin up-regulate expression of PKM2 while hormones like tri-iodothyronine (T3) and glucagon aid in down-regulating PKM2.[29]

Carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP) edit

ChREBP is a transcription factor that regulates expression of the L isozyme of pyruvate kinase.[30] A glucose-sensing module contains domains that are targets for regulatory phosphorylation based on the concentrations of glucose and cAMP, which then control its import into the nucleus.[31] It may also be further activated by directly binding glucose-6-phosphate.[30][32] Once in the nucleus, its DNA binding domains activate pyruvate kinase transcription.[31] Therefore, high glucose and low cAMP causes dephosphorylation of ChREBP, which then upregulates expression of pyruvate kinase in the liver.[30]

Clinical applications edit

Deficiency edit

Genetic defects of this enzyme cause the disease known as pyruvate kinase deficiency. In this condition, a lack of pyruvate kinase slows down the process of glycolysis. This effect is especially devastating in cells that lack mitochondria, because these cells must use anaerobic glycolysis as their sole source of energy because the TCA cycle is not available. For example, red blood cells, which in a state of pyruvate kinase deficiency, rapidly become deficient in ATP and can undergo hemolysis. Therefore, pyruvate kinase deficiency can cause chronic nonspherocytic hemolytic anemia (CNSHA).[33]

PK-LR gene mutation edit

Pyruvate kinase deficiency is caused by an autosomal recessive trait. Mammals have two pyruvate kinase genes, PK-LR (which encodes for pyruvate kinase isozymes L and R) and PK-M (which encodes for pyruvate kinase isozyme M1), but only PKLR encodes for the red blood isozyme which effects pyruvate kinase deficiency. Over 250 PK-LR gene mutations have been identified and associated with pyruvate kinase deficiency. DNA testing has guided the discovery of the location of PKLR on chromosome 1 and the development of direct gene sequencing tests to molecularly diagnose pyruvate kinase deficiency.[34]

Applications of pyruvate kinase inhibition edit

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Inhibition edit

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chemically reactive forms of oxygen. In human lung cells, ROS has been shown to inhibit the M2 isozyme of pyruvate kinase (PKM2). ROS achieves this inhibition by oxidizing Cys358 and inactivating PKM2. As a result of PKM2 inactivation, glucose flux is no longer converted into pyruvate, but is instead utilized in the pentose phosphate pathway, resulting in the reduction and detoxification of ROS. In this manner, the harmful effects of ROS are increased and cause greater oxidative stress on the lung cells, leading to potential tumor formation. This inhibitory mechanism is important because it may suggest that the regulatory mechanisms in PKM2 are responsible for aiding cancer cell resistance to oxidative stress and enhanced tumorigenesis.[35][36]

Phenylalanine inhibition edit

Phenylalanine is found to function as a competitive inhibitor of pyruvate kinase in the brain. Although the degree of phenylalanine inhibitory activity is similar in both fetal and adult cells, the enzymes in the fetal brain cells are significantly more vulnerable to inhibition than those in adult brain cells. A study of PKM2 in babies with the genetic brain disease phenylketonurics (PKU), showed elevated levels of phenylalanine and decreased effectiveness of PKM2. This inhibitory mechanism provides insight into the role of pyruvate kinase in brain cell damage.[37][38]

Pyruvate Kinase in Cancer edit

Cancer cells have characteristically accelerated metabolic machinery and Pyruvate Kinase is believed to have a role in cancer. When compared to healthy cells, cancer cells have elevated levels of the PKM2 isoform, specifically the low activity dimer. Therefore, PKM2 serum levels are used as markers for cancer. The low activity dimer allows for build-up of phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP), leaving large concentrations of glycolytic intermediates for synthesis of biomolecules that will eventually be used by cancer cells.[8] Phosphorylation of PKM2 by Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (ERK2) causes conformational changes that allow PKM2 to enter the nucleus and regulate glycolytic gene expression required for tumor development.[39] Some studies state that there is a shift in expression from PKM1 to PKM2 during carcinogenesis. Tumor microenvironments like hypoxia activate transcription factors like the hypoxia-inducible factor to promote the transcription of PKM2, which forms a positive feedback loop to enhance its own transcription.[8]

Alternatives edit

A reversible enzyme with a similar function, pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK), is found in some bacteria and has been transferred to a number of anaerobic eukaryote groups (for example, Streblomastix, Giardia, Entamoeba, and Trichomonas), it seems via horizontal gene transfer on two or more occasions. In some cases, the same organism will have both pyruvate kinase and PPDK.[40]

References edit

- ^ Gupta V, Bamezai RN (November 2010). "Human pyruvate kinase M2: a multifunctional protein". Protein Science. 19 (11): 2031–44. doi:10.1002/pro.505. PMC 3005776. PMID 20857498.

- ^ Goodman HM (2009). Basic Medical Endocrinology (4th ed.). Elsevier. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-12-373975-9.

- ^ Muirhead H (April 1990). "Isoenzymes of pyruvate kinase". Biochemical Society Transactions. 18 (2): 193–6. doi:10.1042/bst0180193. PMID 2379684. S2CID 3262531.

- ^ Eigenbrodt E, Reinacher M, Scheefers-Borchel U, Scheefers H, Friis R (1992-01-01). "Double role for pyruvate kinase type M2 in the expansion of phosphometabolite pools found in tumor cells". Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 3 (1–2): 91–115. PMID 1532331.

- ^ Noguchi T, Inoue H, Tanaka T (October 1986). "The M1- and M2-type isozymes of rat pyruvate kinase are produced from the same gene by alternative RNA splicing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 261 (29): 13807–12. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)67091-7. PMID 3020052.

- ^ Dombrauckas JD, Santarsiero BD, Mesecar AD (July 2005). "Structural basis for tumor pyruvate kinase M2 allosteric regulation and catalysis". Biochemistry. 44 (27): 9417–29. doi:10.1021/bi0474923. PMID 15996096. S2CID 24625677.

- ^ Chen M, Zhang J, Manley JL (November 2010). "Turning on a fuel switch of cancer: hnRNP proteins regulate alternative splicing of pyruvate kinase mRNA". Cancer Research. 70 (22): 8977–80. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2513. PMC 2982937. PMID 20978194.

- ^ a b c Prakasam G, Iqbal MA, Bamezai RN, Mazurek S (2018). "Posttranslational Modifications of Pyruvate Kinase M2: Tweaks that Benefit Cancer". Frontiers in Oncology. 8: 22. doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00022. PMC 5808394. PMID 29468140.

- ^ a b Valentini G, Chiarelli L, Fortin R, Speranza ML, Galizzi A, Mattevi A (June 2000). "The allosteric regulation of pyruvate kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (24): 18145–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M001870200. PMID 10751408.

- ^ Ramseier TM, Nègre D, Cortay JC, Scarabel M, Cozzone AJ, Saier MH (November 1993). "In vitro binding of the pleiotropic transcriptional regulatory protein, FruR, to the fru, pps, ace, pts and icd operons of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium". Journal of Molecular Biology. 234 (1): 28–44. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1561. PMID 8230205.

- ^ Ramseier TM, Bledig S, Michotey V, Feghali R, Saier MH (June 1995). "The global regulatory protein FruR modulates the direction of carbon flow in Escherichia coli". Molecular Microbiology. 16 (6): 1157–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02339.x. PMID 8577250. S2CID 45447144.

- ^ Saier MH, Ramseier TM (June 1996). "The catabolite repressor/activator (Cra) protein of enteric bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (12): 3411–7. doi:10.1128/jb.178.12.3411-3417.1996. PMC 178107. PMID 8655535.

- ^ Sabnis NA, Yang H, Romeo T (December 1995). "Pleiotropic regulation of central carbohydrate metabolism in Escherichia coli via the gene csrA". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (49): 29096–104. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.49.29096. PMID 7493933.

- ^ Kumar S, Barth A (May 2010). "Phosphoenolpyruvate and Mg2+ binding to pyruvate kinase monitored by infrared spectroscopy". Biophysical Journal. 98 (9): 1931–40. Bibcode:2010BpJ....98.1931K. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4335. PMC 2862152. PMID 20441757.

- ^ Coggins AJ, Powner MW (April 2017). "Prebiotic synthesis of phosphoenol pyruvate by α-phosphorylation-controlled triose glycolysis". Nature Chemistry. 9 (4): 310–317. doi:10.1038/nchem.2624. PMID 28338685. S2CID 205296677.

- ^ Bollenbach TJ, Nowak T (October 2001). "Kinetic linked-function analysis of the multiligand interactions on Mg(2+)-activated yeast pyruvate kinase". Biochemistry. 40 (43): 13097–106. doi:10.1021/bi010126o. PMID 11669648.

- ^ a b c d e Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer J, Clarke ND (2002). Biochemistry (fifth ed.). New York, NY: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3051-4.

- ^ Carbonell J, Felíu JE, Marco R, Sols A (August 1973). "Pyruvate kinase. Classes of regulatory isoenzymes in mammalian tissues". European Journal of Biochemistry. 37 (1): 148–56. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02969.x. hdl:10261/78345. PMID 4729424.

- ^ Yang J, Liu H, Liu X, Gu C, Luo R, Chen HF (June 2016). "Synergistic Allosteric Mechanism of Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate and Serine for Pyruvate Kinase M2 via Dynamics Fluctuation Network Analysis". Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 56 (6): 1184–1192. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00115. PMC 5115163. PMID 27227511.

- ^ Chaneton B, Hillmann P, Zheng L, Martin AC, Maddocks OD, Chokkathukalam A, et al. (November 2012). "Serine is a natural ligand and allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase M2". Nature. 491 (7424): 458–462. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..458C. doi:10.1038/nature11540. PMC 3894725. PMID 23064226.

- ^ Nakatsu D, Horiuchi Y, Kano F, Noguchi Y, Sugawara T, Takamoto I, et al. (March 2015). "L-cysteine reversibly inhibits glucose-induced biphasic insulin secretion and ATP production by inactivating PKM2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (10): E1067-76. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E1067N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417197112. PMC 4364213. PMID 25713368.

- ^ Ishwar A (24 February 2015). "Distinguishing the interactions in the fructose 1,6-bisphosphate binding site of human liver pyruvate kinase that contribute to allostery". Biochemistry. 54 (7): 1516–24. doi:10.1021/bi501426w. PMC 5286843. PMID 25629396.

- ^ Jurica MS, Mesecar A, Heath PJ, Shi W, Nowak T, Stoddard BL (February 1998). "The allosteric regulation of pyruvate kinase by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate". Structure. 6 (2): 195–210. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00021-5. PMID 9519410.

- ^ Li YH, Li XF, Liu JT, Wang H, Fan LL, Li J, Sun GP (August 2018). "PKM2, a potential target for regulating cancer". Gene. 668: 48–53. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2018.05.038. PMID 29775756. S2CID 205030574.

- ^ Birnbaum MJ, Fain JN (January 1977). "Activation of protein kinase and glycogen phosphorylase in isolated rat liver cells by glucagon and catecholamines". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 252 (2): 528–35. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)32749-7. PMID 188818.

- ^ Feliú JE, Hue L, Hers HG (1976). "Hormonal control of pyruvate kinase activity and of gluconeogenesis in isolated hepatocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (8): 2762–6. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.2762F. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.8.2762. PMC 430732. PMID 183209.

- ^ Argaud D, Roth H, Wiernsperger N, Leverve XM (1993). "Metformin decreases gluconeogenesis by enhancing the pyruvate kinase flux in isolated rat hepatocytes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 213 (3): 1341–8. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17886.x. PMID 8504825.

- ^ Clower CV, Chatterjee D, Wang Z, Cantley LC, Vander Heiden MG, Krainer AR (February 2010). "The alternative splicing repressors hnRNP A1/A2 and PTB influence pyruvate kinase isoform expression and cell metabolism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (5): 1894–9. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.1894C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914845107. PMC 2838216. PMID 20133837.

- ^ Iqbal MA, Siddiqui FA, Gupta V, Chattopadhyay S, Gopinath P, Kumar B, et al. (July 2013). "Insulin enhances metabolic capacities of cancer cells by dual regulation of glycolytic enzyme pyruvate kinase M2". Molecular Cancer. 12 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-12-72. PMC 3710280. PMID 23837608.

- ^ a b c Kawaguchi T, Takenoshita M, Kabashima T, Uyeda K (November 2001). "Glucose and cAMP regulate the L-type pyruvate kinase gene by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the carbohydrate response element binding protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (24): 13710–5. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9813710K. doi:10.1073/pnas.231370798. PMC 61106. PMID 11698644.

- ^ a b Ortega-Prieto, Paula; Postic, Catherine (2019). "Carbohydrate Sensing Through the Transcription Factor ChREBP". Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 472. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.00472. ISSN 1664-8021. PMC 6593282. PMID 31275349.

- ^ Richards, Paul; Ourabah, Sarah; Montagne, Jacques; Burnol, Anne-Françoise; Postic, Catherine; Guilmeau, Sandra (2017). "MondoA/ChREBP: The usual suspects of transcriptional glucose sensing; Implication in pathophysiology". Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental. 70: 133–151. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2017.01.033. ISSN 1532-8600. PMID 28403938.

- ^ Grace RF, Zanella A, Neufeld EJ, Morton DH, Eber S, Yaish H, Glader B (September 2015). "Erythrocyte pyruvate kinase deficiency: 2015 status report". American Journal of Hematology. 90 (9): 825–30. doi:10.1002/ajh.24088. PMC 5053227. PMID 26087744.

- ^ Climent F, Roset F, Repiso A, Pérez de la Ossa P (June 2009). "Red cell glycolytic enzyme disorders caused by mutations: an update". Cardiovascular & Hematological Disorders Drug Targets. 9 (2): 95–106. doi:10.2174/187152909788488636. PMID 19519368.

- ^ Anastasiou D, Poulogiannis G, Asara JM, Boxer MB, Jiang JK, Shen M, Bellinger G, Sasaki AT, Locasale JW, Auld DS, Thomas CJ, Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC (December 2011). "Inhibition of pyruvate kinase M2 by reactive oxygen species contributes to cellular antioxidant responses". Science. 334 (6060): 1278–83. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1278A. doi:10.1126/science.1211485. PMC 3471535. PMID 22052977.

- ^ Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC (March 2008). "The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth". Nature. 452 (7184): 230–3. Bibcode:2008Natur.452..230C. doi:10.1038/nature06734. PMID 18337823. S2CID 16111842.

- ^ Miller AL, Hawkins RA, Veech RL (March 1973). "Phenylketonuria: phenylalanine inhibits brain pyruvate kinase in vivo". Science. 179 (4076): 904–6. Bibcode:1973Sci...179..904M. doi:10.1126/science.179.4076.904. PMID 4734564. S2CID 12776382.

- ^ Weber G (August 1969). "Inhibition of human brain pyruvate kinase and hexokinase by phenylalanine and phenylpyruvate: possible relevance to phenylketonuric brain damage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 63 (4): 1365–9. Bibcode:1969PNAS...63.1365W. doi:10.1073/pnas.63.4.1365. PMC 223473. PMID 5260939.

- ^ Yang W, Zheng Y, Xia Y, Ji H, Chen X, Guo F, et al. (December 2012). "ERK1/2-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKM2 promotes the Warburg effect". Nature Cell Biology. 14 (12): 1295–304. doi:10.1038/ncb2629. PMC 3511602. PMID 23178880.

- ^ Liapounova NA, Hampl V, Gordon PM, Sensen CW, Gedamu L, Dacks JB (December 2006). "Reconstructing the mosaic glycolytic pathway of the anaerobic eukaryote Monocercomonoides" (Free full text). Eukaryotic Cell. 5 (12): 2138–46. doi:10.1128/EC.00258-06. PMC 1694820. PMID 17071828.

External links edit

- Pyruvate+kinase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)