Psusennes I (Ancient Egyptian: pꜣ-sbꜣ-ḫꜥ-n-njwt; Greek Ψουσέννης) was the third pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty who ruled from Tanis between 1047 and 1001 BC. Psusennes is the Greek version of his original name Pasibkhanu or Pasebakhaenniut (in reconstructed Late Egyptian: /pəsiwʃeʕənneːʔə/), which means "The Star Appearing in the City" while his throne name, Akheperre Setepenamun, translates as "Great are the Manifestations of Ra, chosen of Amun."[2] He was the son of Pinedjem I and Henuttawy, Ramesses XI's daughter by Tentamun. He married his sister Mutnedjmet.

| Psusennes I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pasebakhenniut I[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

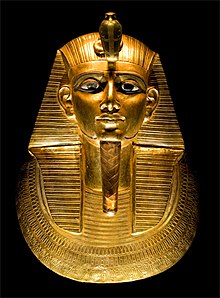

Gold burial mask of King Psusennes I, discovered in 1940 by Pierre Montet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1047–1001 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Amenemnisu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Amenemope | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Mutnodjmet, Wiay | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Amenemope, Ankhefenmut, Isetemkheb C | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Pinedjem I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Henuttawy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | c. 1001 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | NRT III, Tanis | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Great Temple of Amun, Tanis (now in ruined fragments) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | 21st Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Psusennes's tomb, discovered in 1940, is notable for the condition in which it was found. Almost all pharaonic tombs were entirely graverobbed but Psusennes's tomb was one of only two royal tombs discovered in fully intact condition, the other being the tomb of Pharaoh Amenemope. However, the humid climate of Lower Egypt meant only the metal objects had survived.

Reign edit

Psusennes I's precise reign length is unknown because different copies of Manetho's records credit him with a reign of either 41 or 46 years. Some Egyptologists have proposed raising the 41 year figure by a decade to 51 years to more closely match certain anonymous Year 48 and Year 49 dates in Upper Egypt. However, the German Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln has suggested that all these dates should be attributed to the serving High Priest of Amun, Menkheperre instead who is explicitly documented in a Year 48 record.[3] Jansen-Winkeln notes that "in the first half of Dyn. 21, [the] HP Herihor, Pinedjem I and Menkheperre have royal attributes and [royal] titles to differing extents" whereas the first three Tanite kings (Smendes, Amenemnisu and Psusennes I) are almost never referred to by name in Upper Egypt with the exception of one graffito and rock stela for Smendes.[4] In contrast, the name of Psusennes I's Twenty-first Dynasty successors such as Amenemope, Osorkon the Elder, and Siamun appear frequently in various documents from Upper Egypt while the Theban High Priest Pinedjem II who was a contemporary of the latter three kings never adopted any royal attributes or titles in his career.[5]

Hence, two separate Year 49 dates from Thebes and Kom Ombo[6] could be attributed to the ruling High Priest Menkheperre in Thebes instead of Psusennes I but this remains uncertain. Psusennes I's reign has been estimated at 46 years by the editors of the Handbook to Ancient Egyptian Chronology.[7] Psusennes I must have enjoyed cordial relations with the serving High Priests of Amun in Thebes during his long reign since the High Priest Smendes II donated several grave goods to this king which were found in Psusennes II's tomb.

During his long reign, Psusennes built the enclosure walls and the central part of the Great Temple at Tanis which was dedicated to the triad of Amun, Mut and Khonsu.[8] Psusennes was ostensibly the ruler responsible for turning Tanis into a fully-fledged capital city, surrounding its temple with a formidable brick temenos wall with its sanctuary dedicated to Amun being composed of blocks salvaged from the derelict Pi-Ramesses. Many of these blocks were unaltered and kept the name of Pi-Ramesses' builder, Ramesses II, including obelisks still bearing the name of Ramesses II transported from the former capital of Pi-Ramesses to Tanis.[9]

Psusennes had taken his sister, Mutnedjmet, in marriage, in addition to the Lady Wiay. Only two of Psusennes I's children remain identifiable.[10]

Burial edit

Professor Pierre Montet discovered pharaoh Psusennes I's intact tomb (No.3 or NRT III) in Tanis in 1940[11] or 1939. Due to its moist Lower Egypt location, most of the perishable wood objects were destroyed by water – a fate not shared by KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun in the drier climate of Upper Egypt. In contrast to KV62, Psusennes I's tomb holds the distinction of being the only pharaonic grave ever found unscathed by any tomb robbing attempts.[12] The tomb of Tutankhamun had been robbed twice in antiquity.[13]

In spite of the destruction of wooden artifacts within the tomb due to the moist Nile delta area, the king's magnificent funerary mask was recovered intact; it proved to be made of gold and lapis lazuli and held inlays of black and white glass for the eyes and eyebrows of the object.[14] Psusennes I's mask is considered to be "one of the masterpieces of the treasure[s] of Tanis" and is currently housed in Room 2 of the Cairo Museum.[15] It has a maximum width and height of 38 cm and 48 cm respectively.[16] The pharaoh's "fingers and toes had been encased in gold stalls, and he was buried with gold sandals on his feet. The finger stalls are the most elaborate ever found, with sculpted fingernails. Each finger wore an elaborate ring of gold and lapis lazuli or some other semiprecious stone."[17]

Psusennes I's outer and middle sarcophagi had been recycled from previous burials in the Valley of the Kings through the state-sanctioned tomb robbing that was common practice in the Third Intermediate Period. A cartouche on the red outer sarcophagus shows that it had originally been made for Pharaoh Merenptah, the 19th Dynasty successor of Ramesses II. Psusennes I, himself, was interred in an "inner silver coffin" which was inlaid with gold.[18] Since "silver was considerably rarer in Egypt than gold," Psusennes I's silver "coffin represents a sumptuous burial of great wealth during Egypt's declining years."[19]

Dr. Douglas Derry, who worked as the head of Cairo University's Anatomy Department, examined the king's remains in 1940 and determined that the king was an old man when he died.[20] Derry noted that Psusennes I's teeth were badly worn and full of cavities, that he had an abscess that left a hole in his palate, and observed that the king suffered from extensive arthritis and was probably crippled by this condition in his final years.[21]

References edit

- ^ Pasebakhaenniut

- ^ Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 1994., p.178

- ^ Karl Jansen-Winkeln, "Das Ende des Neuen Reiches", Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache, 119 (1992), p.26

- ^ Karl Jansen-Winkeln, "Dynasty 21" in Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David Warburton (editors), Handbook of Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies), Brill: 2006, pp. 226-227, 229

- ^ Hornung, Krauss & Warburton, p. 229

- ^ Kenneth Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100-650 BC), third edition (Aris & Philips, 1996), pp. 421, 573

- ^ Hornung, Krauss & Warburton, p. 493

- ^ Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, (Oxford: Blackwell Books, 1992), pp. 315-317

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (1995). Monarchs of the Nile. London: Rubicon. pp. 155–156. ISBN 094869520X. OCLC 32925121.

- ^ Dodson, Aidan (1995). Monarchs of the Nile. London: Rubicon. p. 156. ISBN 094869520X. OCLC 32925121.

- ^ Bob Brier, Egyptian Mummies: Unravelling the Secrets of an Ancient Art, William Morrow & Company Inc., New York, 1994. p.145

- ^ A., Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs : the reign-by-reign record of the rulers and dynasties of ancient Egypt. New York, N.Y. pp. 180. ISBN 0500050740. OCLC 31639364.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edwards, I.E.S (1976). Treasures of Tutankhamun. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780870991561.

- ^ Lorna Oakes, Pyramids, Temples and Tombs of Ancient Egypt, Hermes House, 2003. p.216

- ^ Alessandro Bongioanni & Maria Croce (ed.), The Treasures of Ancient Egypt: From the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Universe Publishing, a division of Ruzzoli Publications Inc., 2003. p.422

- ^ Bongioanni & Croce, p.422

- ^ Brier, pp.146-147

- ^ Christine Hobson, Exploring the World of the Pharaohs: A complete Guide to Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson 1987. p.123

- ^ Hobson, p.123

- ^ Douglass E. Derry, Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte Vol. 40 (1940), pp.969-970.

- ^ Brier, p.147

Further reading edit

- Bob Brier, Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art, William Morrow & Co, (1994), pp. 146–147.

- Jean Yoyotte, BSSFT 1(1988) 46 n.2.

External links edit

- Secrets of the Dead episode: The Silver Pharaoh (2010)