The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1332–1323 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BC).

| KV62 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Tutankhamun | |

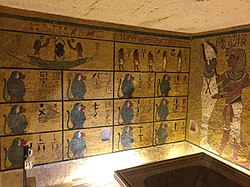

The wall decorations in KV62's burial chamber are modest in comparison with other royal tombs found in the Valley of the Kings. | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′25.4″N 32°36′05.1″E / 25.740389°N 32.601417°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 4 November 1922 |

| Excavated by | Howard Carter |

| Decoration | |

| Layout | Bent to the right |

← Previous KV61 Next → KV63 | |

Tutankhamun's tomb was discovered in 1922 by excavators led by Howard Carter. As a result of the quantity and spectacular appearance of the burial goods, the tomb attracted a media frenzy and became the most famous find in the history of Egyptology. The death of Carter's patron, the Earl of Carnarvon, in the midst of the excavation process inspired speculation that the tomb was cursed. The discovery produced only limited evidence about the history of Tutankhamun's reign and the Amarna Period that preceded it, but it provided insight into the material culture of wealthy ancient Egyptians as well as patterns of ancient tomb robbery. Tutankhamun became one of the best-known pharaohs, and some artefacts from his tomb, such as his golden funerary mask, are among the best-known artworks from ancient Egypt.

Most of the tomb's goods were sent to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and are now in the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, although Tutankhamun's mummy and sarcophagus are still on display in the tomb. Flooding and heavy tourist traffic have inflicted damage on the tomb since its discovery, and a replica of the burial chamber has been constructed nearby to reduce tourist pressure on the original tomb.

History edit

Burial and robberies edit

Tutankhamun reigned as pharaoh between c. 1334 and 1325 BC, towards the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty during the New Kingdom.[1][2] He took the throne as a child after the death of Akhenaten (who was probably his father) and the subsequent brief reigns of Neferneferuaten and Smenkhkare. Akhenaten had radically reshaped ancient Egyptian religion by worshipping a single deity, Aten, and rejecting other deities, a shift that began the Amarna Period.[3] One of Tutankhamun's major acts was the restoration of traditional religious practice. His name was changed from Tutankhaten, referring to Akhenaten's deity, to Tutankhamun, honouring Amun, one of the foremost deities of the traditional pantheon. Similarly, his queen's name was changed from Ankhesenpaaten to Ankhesenamun.[4]

Shortly after Tutankhamun took power, he commissioned a full-size royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings, which was probably one of two tombs from the same era, WV23 or KV57.[5] KV62 is thought to have originally been a non-royal tomb, possibly intended for Ay, Tutankhamun's advisor. After he died prematurely, KV62 was enlarged to accommodate his burial. Ay became pharaoh on Tutankhamun's death and was buried in WV23. Ay was elderly when he came to the throne, and it is possible that he buried Tutankhamun in KV62 in order to usurp WV23 for himself and ensure that he would have a tomb of suitably royal proportions ready when he himself died. Pharaohs in Tutankhamun's time also built mortuary temples where they would receive offerings to sustain their spirits in the afterlife. The Temple of Ay and Horemheb at Medinet Habu contained statues that were originally carved for Tutankhamun, suggesting either that Tutankhamun's temple stood nearby or that Ay usurped Tutankhamun's temple as his own.[6]

Ay was succeeded by Tutankhamun's general Horemheb, although the transfer of power may have been contested and created a brief period of political instability.[7][8] As part of the continued reaction against Atenism, Horemheb tried to erase Akhenaten and his successors from the record, dismantling Akhenaten's monuments and usurping those erected by Tutankhamun. Future king-lists skipped straight from Akhenaten's father, Amenhotep III, to Horemheb.[7]

Within a few years of Tutankhamun's burial, his tomb was robbed twice. After the first robbery, officials responsible for its security repaired and repacked some of the damaged goods before filling the outer corridor with chips of limestone, along with objects dropped by the thieves, to deter future thefts. Nevertheless, a second set of robbers burrowed through the corridor fill. This robbery too was detected, and after a second hasty restoration the tomb was once again sealed.[9]

The Valley of the Kings is subject to periodic flash floods that deposit alluvium.[10] Much of the valley, including the entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb, was covered by a layer of alluvium over which huts were later built for the tomb workers who cut KV57, in which Horemheb was buried. The geologist Stephen Cross has argued that a major flood deposited this layer after KV62 was last sealed and before the huts were built, which would mean Tutankhamun's tomb had been rendered inaccessible by the time Ay's reign ended.[11] However, the Egyptologist Andreas Dorn suggests that this layer already existed during Tutankhamun's reign, and workers dug through it to reach the bedrock into which they cut his tomb.[12]

More than 150 years after Tutankhamun's burial, KV9, the tomb of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI, was cut into the rock to the west of his tomb.[13] The entrance of his tomb was further buried by mounds of debris from KV9's excavation and by the workers' huts atop that debris. In subsequent years the tombs in the valley suffered major waves of robbery: first during the late Twentieth Dynasty by local gangs of thieves, then during the Twenty-first Dynasty by officials working for the High Priests of Amun, who stripped the tombs of their valuables and removed the royal mummies. Tutankhamun's tomb, buried and forgotten, remained undisturbed.[14]

Discovery and clearance edit

Several tombs in the Valley of the Kings lay open continuously from ancient times onward, but the entrances to many others remained hidden until after the emergence of Egyptology in the early nineteenth century.[15] Many of the remaining tombs were found by a series of excavators working for Theodore M. Davis from 1902 to 1914. Under Davis most of the valley was explored, although he never found Tutankhamun's tomb because he thought no tomb would have been cut into the valley floor.[16] Among his discoveries was KV54, a pit containing objects bearing Tutankhamun's name; these objects are now thought to have been either burial goods that were originally stored in the corridor of Tutankhamun's tomb, which were removed and reburied in KV54 when the restorers filled the corridor, or objects related to Tutankhamun's funeral. Davis's excavators also discovered a small tomb called KV58 that contained pieces of a chariot harness bearing the names of Tutankhamun and Ay. Davis was convinced that KV58 was Tutankhamun's tomb.[17]

After Davis gave up work on the valley, the archaeologist Howard Carter and his patron George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, made an effort to clear the valley of debris down to the bedrock. Davis's finds of artefacts bearing Tutankhamun's name gave them reason to hope they might find his tomb.[18] The discovery began on 4 November 1922 with a single step at the top of the entrance staircase.[19] When the excavators reached the antechamber, on 26 November, it exceeded all expectations, providing unprecedented insight into what a New Kingdom royal burial was like.[20]

The condition of the burial goods varied greatly; many had been profoundly affected by moisture, which probably derived from both the damp state of the plaster when the tomb was first sealed and from water seepage over the millennia until it was excavated.[21] Recording the tomb's contents and conserving them so they could survive to be transported to Cairo proved to be an unprecedented task, lasting for ten digging seasons.[22][23] Although many others participated, the only members of the excavation team who worked throughout the process were Carter, Alfred Lucas (a chemist who was instrumental in the conservation effort), Harry Burton (who photographed the tomb and its artefacts) and four foremen: Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said.[24]

The spectacular nature of the tomb goods inspired a media frenzy, dubbed "Tutmania", that made Tutankhamun into one of the most famous pharaohs, often known by the nickname "King Tut".[25][26] In the Western world the publicity inspired a fad for ancient Egyptian-inspired design motifs.[27] In Egypt it reinforced the ideology of pharaonism, which emphasized modern Egypt's connection to its ancient past and had risen to prominence during Egypt's struggle for independence from British rule from 1919 to 1922.[28] The publicity increased when Carnarvon died of an infection in April 1923, inspiring rumours that he had been killed by a curse on the tomb. Other deaths or strange events connected with the tomb came to be attributed to the curse as well.[29]

After Carnarvon's death, the tomb clearance continued under Carter's leadership. In the second season of the process, in late 1923 and early 1924, the antechamber was emptied of artefacts and work began on the burial chamber.[30] The Egyptian government, which had become partially independent in 1922, fought with Carter over the question of access to the tomb; the government felt that Egyptians, and especially the Egyptian press, were given too little access. In protest of the government's increasing restrictions, Carter and his associates stopped work in February 1924, beginning a legal dispute that lasted until January 1925. Under the agreement that resolved the dispute, the artefacts from the tomb would not be divided between the government and the dig's sponsors, as had been standard practice on previous Egyptological digs.[31] Instead most of the tomb's contents went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[32]

The excavators opened and removed Tutankhamun's coffins and mummy in 1925, then spent the next few seasons working on the treasury and annexe. The clearance of the tomb itself was completed in November 1930, though Carter and Lucas continued to work on conserving the remaining burial goods until February 1932, when the last shipment was sent to Cairo.[33]

Tourism and preservation edit

The tomb has been a popular tourist destination ever since the clearance process began.[34] Sometime after the mummy was reinterred in 1926, someone broke into the sarcophagus, stealing objects Carter had left in place. A likely time for the event is the Second World War, when a shortage of security workers led to widespread looting of Egyptian antiquities. The body was subsequently rewrapped, suggesting local officials may have discovered the break-in and restored the mummy without reporting what had happened. The theft was not exposed until 1968, after the anatomist Ronald Harrison re-examined Tutankhamun's remains.[35]

Most tombs in the Valley of the Kings tombs are vulnerable to flash flooding.[36] When analysing Tutankhamun's tomb in 1927, Lucas concluded that despite the moisture seepage, no significant liquid water had entered before its discovery.[37] In contrast, since the discovery water has periodically trickled in through the entrance, and on New Year's Day in 1991 a rainstorm flooded the tomb through a fault in the burial chamber ceiling. The flood stained the painted chamber wall and left about 7 centimetres (2.8 in) of standing water on the floor.[38] Tombs are also threatened by the tourists who visit them, who may damage the wall decoration with their touch and with the moisture introduced by their breath.[36] The mummy is also vulnerable to this kind of damage, so in 2007 it was moved to a climate-controlled glass display case that was placed in the antechamber, allowing it to be displayed to the public while protecting it from humidity and mould.[39]

The Society of Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt suggested the idea of creating a replica of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1988, so that tourists could see it without further damaging the original.[40] In 2009, Factum Arte, a workshop that specialises in replicas of large-scale artworks, took detailed scans of the burial chamber on which to base a replica,[40] while the Egyptian government and the Getty Conservation Institute launched a long-term project to assess the condition of the tomb and renovate it as needed.[41] The replica was completed in 2012 and opened to the public in 2014;[40] the renovation was completed in 2019.[42]

In 2015, the Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves argued, based on Factum Arte's scans, that the west and north walls of the burial chamber included previously unnoticed plaster partitions. That would suggest the tomb contained two previously unknown chambers, one behind each partition, which Reeves suggested were the burial place of Neferneferuaten. The Ministry of Antiquities commissioned a ground-penetrating radar examination later that year, which seemed to show voids behind the chamber walls, but follow-up radar examinations in 2016 and 2018 determined that there are no such voids and therefore no hidden chambers.[43]

Tutankhamun's tomb is in higher demand from tourists than any other in the Valley of the Kings. Up to 1,000 people pass through it on its busiest days.[44]

Architecture edit

Tutankhamun's tomb lies in the eastern branch of the Valley of the Kings, where most tombs in the valley are located.[45] It is cut into the limestone bedrock in the valley floor, on the west side of the main path, and runs beneath a low foothill.[46] Its design is similar to those of non-royal tombs from its time, but elaborated so as to resemble the conventional plan of a royal tomb.[47] It consists of a westward-descending stairway (labeled A in the conventional Egyptological system for designating parts of royal tombs in the valley); an east–west descending corridor (B); an antechamber at the west end of the passage (I); an annexe adjoining the southwest corner of the antechamber (Ia); a burial chamber north of the antechamber (J); and a room east of the burial chamber (Ja), known as the treasury.[48] The burial chamber and treasury may have been added to the original tomb when it was adapted for Tutankhamun's burial.[47] Most Eighteenth Dynasty royal tombs used a layout with a bent axis, so that a person moving from the entrance to the burial chamber would take a sharp turn to the left along the way. By placing Tutankhamun's burial chamber north of the antechamber, the builders of KV62 gave it a layout with an axis bent to the right rather than the left.[49][50]

The entrance stair descends steeply beneath an overhang.[5] It originally consisted of sixteen steps. The lowest six were cut away during the burial to make room to maneuver the largest pieces of funerary furniture through the doorway, then rebuilt, then removed again 3,400 years later when the excavators removed that same furniture. The corridor is 8 metres (26 ft) long and 1.7 metres (5 ft 7 in) wide; the antechamber is 7.9 metres (26 ft) north–south by 3.6 metres (12 ft) east–west; the annexe is 4.4 metres (14 ft) north–south by 2.6 metres (8 ft 6 in) east–west; the burial chamber is 4 metres (13 ft) north–south by 6.4 metres (21 ft) east–west; and the treasury is 4.8 metres (16 ft) north–south by 3.8 metres (12 ft) east–west. The chambers range from 2.3 metres (7 ft 7 in) to 3.6 metres (12 ft) high, and the floors of the annexe, burial chamber and treasury are about 0.9 metres (2 ft 11 in) below the floor of the antechamber. In the west wall of the antechamber is a small niche for a beam that was used for manoeuvring the sarcophagus through the room.[51] The burial chamber contains four niches, one in each wall, in which were placed "magic bricks" inscribed with protective spells.[51][52]

Partitions constructed of limestone and plaster originally sealed the doorways between the stairway and the corridor; between the corridor and the antechamber; between the antechamber and the annexe; and between the antechamber and the burial chamber. All were breached by robbers. Most were resealed by the restorers, but the robbers' hole in the annexe doorway was left open.[53]

There are several faults in the rock into which the tomb is cut, including a large one that runs south-southeast to north-northwest across the antechamber and burial chamber.[54] Although the workmen who cut the tomb sealed the fault in the burial chamber with plaster,[55] the faults are responsible for the water seepage that affects the tomb.[54]

Decoration edit

The plaster partitions were marked with impressions from seals borne by various officials who oversaw Tutankhamun's burial and the restoration efforts. These seals consist of hieroglyphic text that celebrates Tutankhamun's services to the gods during his reign.[57]

Aside from these seal impressions, the only wall decoration in the tomb is in the burial chamber. This limited decorative programme contrasts with other royal tombs of the late Eighteenth Dynasty, in which two chambers in addition to the burial chamber often received decoration, and with the practice in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, in which all parts of the tomb were decorated. None of the decoration is executed in relief, a technique that was not used in the Valley of the Kings until the reign of Horemheb.[58]

KV62's burial chamber is painted with figures on a yellow background. The east wall portrays Tutankhamun's funeral procession, a type of image that is common in private New Kingdom tombs but not found in any other royal tomb. The north wall shows Ay performing the Opening of the Mouth ritual upon Tutankhamun's mummy, thus legitimising himself as the king's heir, and then Tutankhamun greeting the goddess Nut and the god Osiris in the afterlife. The south wall portrayed the king with the deities Hathor, Anubis and Isis. Part of the decoration of this wall was painted on the partition dividing the burial chamber from the antechamber, and thus the figure of Isis had to be destroyed by Carter when the partition was demolished during the tomb clearance. The west wall bears an image of twelve baboons, which is an extract from the first section of the Amduat, a funerary text that describes the journey of the sun god Ra through the netherworld. On three walls the figures are given the unusual proportions found in the art style of the Amarna Period, although the south wall reverts to the conventional proportions found in art before and after Amarna.[59]

-

Scenes from the west wall of the burial chamber showing images of twelve baboons, which is an extract from the first section of the Amduat, a funerary text that describes the journey of the sun god Ra through the netherworld.

-

Scenes from the east wall of the burial chamber showing court officials dragging Tutankhamun's mummy to his tomb. Horemheb is possibly depicted as the person closest to Tutankhamun's mummy.

Burial goods edit

The contents of the tomb are by far the most complete example of a royal set of burial goods in the Valley of the Kings,[60] numbered at 5,398 objects.[61] Some classes of object number in the hundreds: there are 413 shabtis (figurines intended to do work for the king in the afterlife) and more than 200 pieces of jewellery.[62] Objects were present in all four chambers in the tomb as well as the corridor.[63]

The efforts of the robbers, followed by the hasty restoration effort, left much of the tomb in disarray when it was last sealed.[64] By the time of the discovery, many of the objects had been damaged by alternating periods of humidity and dryness.[65] Nearly all leather in the tomb had dissolved into a pitch-like mass, and while the state of preservation of textiles was highly inconsistent, the worst-preserved had turned into a black powder.[66] Wooden objects were warped and their glues dissolved, leaving them in a very fragile state.[65] Every exposed surface was covered with an unidentified pink film;[67] Lucas suggested it was some kind of dissolved iron compound that came from the rock or the plaster.[68] In the process of cleaning, restoring and removing the damaged artefacts, the excavators labeled each object or group of objects with a number, from 1 to 620, appending letters to distinguish individual objects within a group.[69]

Outer chambers edit

The corridor may have contained miscellaneous materials, such as bags of natron, jars and flower garlands, that were moved to KV54 when the corridor was filled after the first robbery.[63] Other objects and fragments were incorporated into the corridor fill. One well-known artefact, a wooden bust of Tutankhamun, was apparently found in the corridor when it was excavated, but it was not recorded in Carter's initial excavation notes.[70]

The antechamber contained 600 to 700 objects. Its west side was taken up by a tangled pile of furniture among which miscellaneous small objects, such as baskets of fruit and boxes of meat, were placed. Several dismantled chariots took up the southeast corner, while the northeast contained a collection of funerary bouquets and the north end of the chamber was dominated by two life-size statues of Tutankhamun that flanked the entrance to the burial chamber.[71] These statues are thought to have either served as guardians of the burial chamber or as figures representing the king's ka, an aspect of his soul.[72] Among the significant objects in the antechamber were several funerary beds with animal heads, which dominated the cluster of furniture against the west wall; an alabaster lotus chalice; and a painted box depicting Tutankhamun in battle, which Carter regarded as one of the finest works of art in the tomb. Carter thought even more highly of a gilded and inlaid throne depicting Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun in the art style of the Amarna Period; he called it "the most beautiful thing that has yet been found in Egypt".[73] Boxes in the antechamber contained most of the clothing in the tomb, including tunics, shirts, kilts, gloves and sandals, as well as cosmetics such as unguents and kohl.[74] Scattered in various places in the antechamber were pieces of gold and semiprecious stones from a corselet, a ceremonial version of the armor that Egyptian kings wore into battle. Reconstructing the corselet was one of the most complex tasks the excavators faced.[75] This room also contained a wooden dummy of Tutankhamun's head and torso. Its purpose is uncertain, although it bears marks that may indicate it once wore a corselet, and Carter suggested it was a mannequin for the king's clothes.[76]

The annexe contained more than 2,000 individual artefacts. Its original contents were jumbled together with objects that had been haphazardly replaced during the restoration after the robberies, including beds, stools, and stone and pottery vessels containing wine and oils.[77] The room housed most of the tomb's foodstuffs, most of the shabtis and many of its wooden funerary models, such as models of boats.[78] Much of the weaponry in the tomb, such as bows, throwing sticks and khopesh-swords, as well as ceremonial shields, were found here.[79] Other objects in the annexe were personal possessions that Tutankhamun seemingly used as a child, such as toys, a box of paints and a fire-lighting kit.[80]

-

A bust of Tutankhamun found in the corridor

-

A painted chest from the antechamber

-

A chariot, reassembled from the pieces in the antechamber

-

Two of the embroidered gloves found in the antechamber and annexe[81]

-

Ceremonial shield from the annexe

-

A calcite model boat from the annexe

-

A senet game-board from the annexe

-

Shabtis, many of which were found in the annexe

Burial chamber edit

Most of the space in the burial chamber was taken up by the gilded wooden outer shrine enclosing three nested inner shrines and, within them, a stone sarcophagus containing three nested coffins. Also a wooden frame stood between the outermost and second shrines which was covered with a blue linen pall spangled with bronze rosettes. Yet even this chamber contained burial goods, including jars, religious objects such as imiut fetishes, oars, fans and walking sticks, some of which were inserted in the narrow gaps between shrines.[82] Each wall of the chamber bore a niche containing a brick,[83] of a type that Egyptologists call "magic bricks", because they are inscribed with passages from Spell 151 from the funerary text known as the Book of the Dead, and are intended to ward off threats to the dead.[52]

The decoration of the shrines, executed in relief, includes portions of several funerary texts. All four shrines bear extracts from the Book of the Dead, and further extracts from the Amduat are on the third shrine.[84] The outermost shrine is inscribed with the earliest known copy of the Book of the Heavenly Cow, which describes how Ra reshaped the world into its current form.[85] The second shrine bears a funerary text that is found nowhere else, although texts with similar themes are known from the tombs of Ramesses VI (KV9) and Ramesses IX (KV6). Like them, it describes the sun god and the netherworld using a cryptic form of hieroglyphic writing that uses non-standard meanings for each hieroglyphic sign. These three texts are sometimes labeled "enigmatic books" or "books of the solar-Osirian unity".[86][87]

The sarcophagus is made of quartzite but with a red granite lid, painted yellow to match the quartzite. It is carved with the images of four protective goddesses (Isis, Nephthys, Neith and Serqet), and contained a golden lion-headed bier on which rested three nested coffins in human shape. The outer two coffins were made of gilded wood inlaid with glass and semiprecious stones, while the innermost coffin, though similarly inlaid, was primarily composed of 110.4 kilograms (243 lb) of solid gold.[88] Within it lay Tutankhamun's mummified body. On the body, and contained within the layers of mummy wrappings, were 143 items, including articles of clothing such as sandals, a plethora of amulets and other jewellery and two daggers. Tutankhamun's head bore a beaded skullcap and a gold diadem, all of which was encased in the golden mask of Tutankhamun, which has become one of the most iconic ancient Egyptian artefacts in the world.[89]

-

Imiut fetishes from the burial chamber

-

Diagram of shrines and coffins in the tomb

-

The middle coffin, from the burial chamber

-

The inner coffin, from the burial chamber

-

The iron dagger, found on Tutankhamun's body

Treasury edit

In the doorway of the treasury stood a shrine on carrying poles topped by a statue of the jackal god Anubis, in front of which lay a fifth magic brick.[90] Against the east wall of the treasury was a tall gilded shrine containing the canopic chest, in which Tutankhamun's internal organs were placed after mummification. Whereas most canopic chests contain separate jars, Tutankhamun's consists of a single block of alabaster carved into four compartments, each covered by a human-headed stopper and containing an inlaid gold coffinette that housed one of the king's organs.[91] Between the Anubis shrine and the canopic shrine stood a wooden sculpture of a cow's head, representing the goddess Hathor. The treasury was the location of most of the tomb's wooden models, including more boats and a model granary, as well as many of the shabtis.[92] Boxes in the treasury contained miscellaneous items, including much of the tomb's jewellery.[93] A nested set of small coffins in the treasury contained a lock of hair belonging to Tiye, the wife of Amenhotep III, who is thought to have been Tutankhamun's grandmother. One box contained two miniature coffins in which mummies of Tutankhamun's stillborn daughters were interred.[94]

-

Portable shrine with a statue Anubis, exposition in Paris

-

The Anubis shrine, from the entrance to the treasury

-

A box from the treasury shaped like the cartouche of Tutankhamun's name

-

A pendant in the shape of a winged scarab carrying the Eye of Horus, from the treasury

-

The canopic shrine from the treasury

-

The canopic chest from the treasury, with three of the four stoppers present

-

Figurines of deities, found in the treasury

Significance edit

The volume of goods in Tutankhamun's tomb is often taken as a sign that longer-lived kings who had full-size tombs were buried with an even larger array of objects. Yet Tutankhamun's burial goods barely fit into his tomb, so the Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley argues that larger tombs in the valley may have contained assemblages of similar size that were arranged in a more orderly and spacious manner.[95]

The fragmentary remains of burial goods in other tombs in the Valley of the Kings include many of the same objects found in Tutankhamun's, implying that there was a somewhat standard set of object types for royal burials in this era. The life-size statues of Tutankhamun and the statuettes of deities have parallels in several other tombs in the valley, while the statuettes of Tutankhamun himself are closely paralleled by wall paintings in KV15, the tomb of Seti II. Funerary models, such as Tutankhamun's model boats, were mainly a feature of burials in the Old and Middle Kingdoms and fell out of favour in non-royal burials in the New, but several royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings contained them. Conversely, Tutankhamun's tomb contained no funerary texts on papyri, unlike private tombs from its era, but the existence of an excerpt of the Book of the Dead on a papyrus from KV35, the tomb of Amenhotep II, suggests that their absence in Tutankhamun's tomb may have been unusual.[97]

No papyrus texts at all were among the burial goods—a disappointment to Egyptologists, who hoped to find documents that would clarify the history of the Amarna Period. Instead much of the value of the discovery was in the insight it provided into the material culture of ancient Egypt.[98] Among the furniture was a foldable bed, the only intact example known from ancient Egypt.[99] Some of the boxes could be latched with the turn of a knob, and Carter called them the oldest known examples of such a mechanism.[100] Other everyday items include musical instruments, such as a pair of trumpets; a variety of weapons, including a dagger made of iron, a rare commodity in Tutankhamun's time; and about 130 staffs, including one bearing the label "a reed staff which His Majesty cut with his own hand."[101]

Tutankhamun's clothes—loose tunics, robes and sashes, often elaborately decorated with dye, embroidery or beadwork—exhibit more variety than the clothes depicted in art from his time, which consist largely of plain white kilts and tight sheaths. No crowns were found in the tomb, although crooks and flails, which also served as emblems of kingship, were stored there. Tyldesley suggests that crowns may have not been considered personal property of the king and were instead passed down from reign to reign.[102]

Some of the objects in the tomb shed limited light on the end of the Amarna Period. A piece of a box found in the corridor bears the names of Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten and Akhenaten's daughter Meryetaten, while a calcite jar from the tomb bore two erased royal names that have been reconstructed as those of Akhenaten and Smenkhkare. These are key pieces of evidence in attempts to reconstruct the relationships between members of the royal family and the sequence in which they reigned, although scholars' interpretations have varied greatly.[103][104] The faces of Tutankhamun's second coffin and his canopic coffinettes differ from the faces of most portrayals of him, so these items may originally have been made for another ruler, such as Smenkhkare or Neferneferuaten, and reused for Tutankhamun's burial.[105][106]

Some objects bear evidence of the shift in religious policy in Tutankhamun's reign.[108] The golden throne portrays Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun beneath the rays of the Aten, in the Amarna art style.[107] The king and queen are labeled with the later forms of their names, referring to Amun rather than the Aten, but there are signs that these labels were altered after the throne was made, and the open-work arms and back of the throne bear the king's original name, Tutankhaten.[108] A sceptre from the annexe bears an inscription mentioning both the Aten and Amun, implying an attempt to integrate the two religious systems.[109]

Other information about the reign is provided by wine jars, which are labeled by the year in which they were produced. Jars that are explicitly labeled as coming from Tutankhamun's reign range from Year 5 to Year 9, while one jar from an unidentified reign is labeled Year 10 and another Year 31. The Year 31 wine probably comes from the reign of Amenhotep III, so the remaining jars suggest that Tutankhamun reigned for nine or ten years.[2][110] The flowers and fruits in the funerary garlands would have been available from mid-March to mid-April, indicating that Tutankhamun's funeral took place then.[111] The royal annals of the Hittite Empire record a letter from an unnamed Egyptian queen, referred to as "Dakhamunzu", recently widowed by the death of a pharaoh and offering to marry a Hittite prince. The dead king is most commonly thought to be Tutankhamun, and Ankhesenamun the sender of the letter, but the letter indicates the king in question died in August or September, meaning either that Tutankhamun was not the king in the Hittite annals or that he remained unburied far longer than the traditional 70-day period of mummification and mourning.[112]

The thefts make Tutankhamun's tomb one of the most important sources for understanding tomb robbery and restoration in the New Kingdom, particularly for the early part of that period, when robberies were more opportunistic than the large-scale plundering that took place in the late Twentieth Dynasty.[113] Many of the boxes in the tomb bear dockets in hieratic writing that list their original contents, making it possible to partially reconstruct what the tomb originally held and which items were lost. The dockets of the jewellery boxes in the treasury, for instance, indicate that about 60 percent of their contents is missing.[114] Thieves would have prized what was valuable, portable and either untraceable or possible to disguise through dismantling or melting.[115] Most of the metal vessels originally buried with Tutankhamun were stolen, as were those of glass, indicating that glass was a valuable commodity at the time. The robbers also took bedding and cosmetics; the theft of the latter shows that the robberies took place soon after burial, as the Egyptians' fat-based unguents would have turned rancid within a few years.[116] One of the boxes in the antechamber contained a set of gold rings wrapped in a scarf, which Carter believed had been dropped by the thieves and placed in the box by the restorers. The unlikelihood that robbers would forget something so valuable led him to suggest they had been caught in the act.[117] The broken objects found in the fill of the corridor all came from the antechamber, implying that the first group of thieves only had access to that chamber and that it was the second group who reached as far as the treasury.[118]

A man named Djehutymose, apparently the official who carried out the restoration of the tomb, wrote his name on a jar stand in the annexe. The same man left a note in KV43, the tomb of Thutmose IV, recording the restoration of that tomb in Year 8 of the reign of Horemheb.[119] These two tombs were among several in the Valley of the Kings that were robbed at the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty, suggesting that political uncertainty following Tutankhamun's death caused a weakening of security there.[8]

Disposition edit

After the completion of the clearance in 1932, the tomb was emptied of nearly all its contents. The main exceptions were the sarcophagus, with its original lid replaced by a glass plate, and the outermost of the three coffins, in which Tutankhamun's mummy was placed.[120][121] Carter also took a handful of small artefacts from the tomb, without permission; upon his death, his heir, Phyllis Walker, discovered them and had them returned to the Egyptian government. A few items are suspected of having illicitly made their way into other collections of Egyptian antiquities, but their provenance is uncertain.[122]

For several decades after his tomb was cleared, the overwhelming majority of Tutankhamun's burial goods were stored at either the Egyptian Museum in Cairo or Luxor Museum. Only the most major pieces have been on display, while the rest have been in storage at one of the two sites.[32] Selected pieces have also gone on museum exhibition tours, raising money for the Egyptian government[32] and serving to improve its relations with the host countries.[123] There have been several exhibitions, visiting Europe, North America, Japan and Australia, in three major phases, one from 1961 to 1967, another from 1972 to 1981, and a third from 2004 to 2013. Many exhibitions of replicas have also taken place, beginning with a set made for the British Empire Exhibition in 1924.[124]

Beginning in 2011, the objects from the tomb were gradually transferred to the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza.[125] Upon its opening, the museum is planned to display all the tomb's artefacts.[126]

Mummies edit

When it was uncovered in November 1925, Tutankhamun's mummy was in poor condition.[129] The unguents that were poured over the wrappings before burial had undergone a chemical reaction that Lucas called "some kind of slow spontaneous combustion", possibly caused by fungi in the tomb.[130] As a result most of the wrappings, and even much of the tissues in the mummy, had been carbonised.[131] Tutankhamun's condition contrasted with the much better-preserved mummies of other New Kingdom rulers.[132] These mummies had been removed from their plundered tombs, placed in simpler coffins and buried in two caches during the Twenty-first Dynasty, a few centuries after they were originally entombed.[133] It is not known whether they suffered less deterioration because they were less liberally treated with unguents, or because their removal from their original coffins prevented the unguents from soaking through the wrappings.[131][132]

The solidified unguents glued together Tutankhamun's remains, his mummy wrappings and the objects on his body, forming a single mass stuck to the bottom of the coffin encasing it. The excavators concluded that to remove the mummy and extricate the burial goods they would have to cut it into sections, chiseling each piece out of its setting. Two anatomists, Douglas Derry and Saleh Bey Hamdi, examined the pieces as they came free before coating the fragile flesh in paraffin wax to prevent further deterioration.[134] They determined that Tutankhamun had been close to the age of 18 when he died, and that his skull shape, closely resembling that of an unidentified royal mummy from KV55, showed he was of royal blood rather than having married into the royal family, as Egyptologists had previously believed.[135][136] When the examination concluded, Carter placed the dismembered mummy on a sand tray, which he returned to the sarcophagus in the burial chamber the following year.[137]

The mummified fetuses found in the treasury are at different stages of development, one at five months' gestation and the other at seven to nine. Their coffins do not specify names, so they are designated based on the object number of the box that contained them (317); the smaller fetus is known as 317a(2) and the larger as 317b(2).[138] They were examined by Derry in 1932[139] and subsequently stored at the medical school where he worked, now part of Cairo University.[140]

Tutankhamun's mummy has often been analysed to see what health conditions he had, and particularly to determine his cause of death. Such efforts are often contentious, as it is difficult to distinguish damage inflicted on the body in recent times from damage Tutankhamun suffered while alive. For instance, in 1996, the Egyptologist Bob Brier suggested that fragments of bone in the skull cavity, seen in the X-rays that Harrison had taken in 1968, were a sign that Tutankhamun had died of a blow to the head and might have been murdered. The bone fragments were later found to be fragments of vertebrae that were pushed into the skull cavity during Derry's examination.[141][142] The fetuses have faced similar problems; Harrison, in 1977, said 317b(2) had Sprengel's deformity, but a study in 2011 by the radiologist Sahar Saleem argued that the signs of deformity were actually postmortem damage.[143]

Both Tutankhamun's mummy and the fetuses have undergone genetic testing. A 2010 study of the DNA of many of the mummies from the Valley of the Kings announced that the fetuses were Tutankhamun's children by a woman whose mummy was found in KV21, who was presumed to be Ankhesenamun. However, the results of genetic studies of Egyptian mummies have been questioned by several geneticists, such as Svante Pääbo, who argue that DNA breaks down so rapidly in Egypt's heat that remains more than a few centuries old cannot produce an analysable DNA sample.[144]

Replica edit

The replica of the burial chamber includes copies of the wall decoration and of the sarcophagus. Both were reproduced based on highly detailed scans. The replica was presented to the Egyptian government in 2012 and installed next to Carter House, where Carter lived while working on the tomb, near the entrance to the Valley of the Kings.[40][145]

References edit

Citations edit

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 24.

- ^ a b Tyldesley 2012, p. 165.

- ^ Williamson 2015, pp. 1, 4, 9–10.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 17, 205–206.

- ^ a b Roehrig 2016, p. 196.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Reeves 1990, p. 33.

- ^ a b Goelet 2016, pp. 450–451.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 20.

- ^ Ridley 2019, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Dorn 2016, p. 32.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 9, 11.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 28–31.

- ^ Thompson 2015, pp. 246, 251–252, 255.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Thompson 2018, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 94, 98, 103.

- ^ Lucas 2001, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Carter & Mace 2003, p. 105.

- ^ Carter 2000, p. vi.

- ^ Riggs 2019, pp. 9, 12.

- ^ Thompson 2018, p. 49.

- ^ Riggs 2021, p. 93.

- ^ Thompson 2018, p. 50.

- ^ Reid 2015, pp. 42, 52.

- ^ Thompson 2018, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 85, 87–88.

- ^ Reid 2015, pp. 63, 68–70.

- ^ a b c Forbes 2018, p. 350.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 94, 98–100.

- ^ Riggs 2021, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 210.

- ^ Lucas 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Romer & Romer 1993, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b c d Factum Foundation.

- ^ Getty 2013.

- ^ CBS News 2019.

- ^ Forbes 2018, pp. 356–362.

- ^ Riggs 2021, p. 299.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 11, 17.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 36, 70.

- ^ a b Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 124.

- ^ Roehrig 2016, pp. 187, 196.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 25, 124.

- ^ Roehrig 2016, pp. 191, 196.

- ^ a b Reeves 1990, p. 70.

- ^ a b Ritner 1997, p. 146.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 70–71, 96.

- ^ a b Reeves 1990, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Romer & Romer 1993, p. 24.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 33, 35, 124.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 37, 124–125.

- ^ Price 2016, p. 274.

- ^ Marchant 2013, p. 79.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 136, 150.

- ^ a b Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 95, 97.

- ^ a b Carter 2001, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Lucas 2001, pp. 175–176, 185.

- ^ Carter 2000, p. 163.

- ^ Lucas 2000, p. 172.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Hawass 2007, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 78–81, 204, 206.

- ^ Price 2016, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Hawass 2007, pp. 24, 27, 32, 56.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 173–175.

- ^ Hawass 2007, p. 64.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 136, 142, 205.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 174–177.

- ^ Marchant 2013, p. 78.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 83–85, 100–101.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 71.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 101–104.

- ^ Hornung 1999, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Hornung 1999, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Roberson 2016, pp. 327–328.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 105–110.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 62, 66–71.

- ^ Carter 2000, p. 33.

- ^ Hawass 2007, pp. 157, 167, 170.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 134, 136, 142–145.

- ^ Hawass 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 77, 118, 188.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 153.

- ^ Price 2016, pp. 275–280, 285.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 182.

- ^ Carter 2000, p. 121.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 163–164, 177–178.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 108–110.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 252.

- ^ Tawfik, Thomas & Hegenbarth-Reichardt 2018, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Forbes 2018, pp. 143.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 306.

- ^ a b Hawass 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Tyldesley 2012, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 153.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 202.

- ^ Newberry 2001, p. 196.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 224.

- ^ Goelet 2016, pp. 451–453.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 96–97, 190.

- ^ Goelet 2016, p. 452.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 96, 197, 200.

- ^ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 97.

- ^ Marchant 2013, p. 74.

- ^ Riggs 2021, p. 108.

- ^ Riggs 2021, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Riggs 2021, pp. 179–181, 228–229.

- ^ Forbes 2018, pp. 350–352.

- ^ Tawfik, Thomas & Hegenbarth-Reichardt 2018, p. 179.

- ^ El Sawy 2021.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 117.

- ^ Marchant 2013, p. 97.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 64, 66.

- ^ Lucas 2001, pp. 185–186.

- ^ a b Carter 2001, pp. 101–102.

- ^ a b Marchant 2013, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 207.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 62–64, 70–71.

- ^ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Marchant 2013, p. 72.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Reeves 1990, p. 123.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 65, 109, 135.

- ^ Reeves 1990, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 145–149.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 119, 235.

- ^ Marchant 2013, pp. 187–188, 201.

- ^ Forbes 2018, pp. 344–347.

Works cited edit

- Carter, Howard; Mace, A. C. (2003) [1923]. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume I: Search, Discovery and Clearance of the Antechamber. Duckworth. ISBN 978-071563172-0.

- Carter, Howard (2001) [1927]. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume II: The Burial Chamber. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0715630754.

- Carter, Howard (2000) [1933]. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume III: The Annexe and Treasury. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0715629642.

- "Conservation and Management of the Tomb of Tutankhamen". The Getty. Getty Conservation Institute. March 2013. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- Dorn, Andreas (2016). "The Hydrology of the Valley of the Kings". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–38. ISBN 978-0199931637.

- El Sawy, Nada (8 June 2021). "Most King Tutankhamun displays ready at Grand Egyptian Museum". The National. Vol. 74.

- "The Facsimile of Tutankhamun's Tomb: Overview". Factum Foundation. Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- Forbes, Dennis C. (2018) [first edition 1998]. Tombs, Treasures, Mummies: Seven Great Discoveries of Egyptian Archaeology in Five Volumes. Book Four: The Tomb of Tutankhamen (KV62). Kmt Communications, LLC. ISBN 978-1981423385.

- Goelet, Ogden (2016). "Tomb Robberies in the Valley of the Kings". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 448–466. ISBN 978-0199931637.

- Hawass, Zahi (2007). King Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Tomb. Photographs by Sandro Vannini. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500051511.

- Hornung, Erik (1999). The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801485152.

- "King Tut's tomb unveiled after being restored to its ancient splendor". CBS News. CBS Interactive Inc. 2 February 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- Lucas, Alfred (2001) [1927]. "Appendix II: The Chemistry of the Tomb". The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume II: The Burial Chamber. By Carter, Howard. Duckworth. pp. 162–188. ISBN 978-0715630754.

- Lucas, Alfred (2000) [1933]. "Appendix II: The Chemistry of the Tomb". The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume III: The Annexe and Treasury. By Carter, Howard. Duckworth. pp. 170–183. ISBN 978-0715629642.

- Marchant, Jo (2013). The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306821332.

- Newberry, Percy (2001) [1927]. "Appendix III: Report on the Floral Wreaths found in the Coffins of Tut.Ankh.Amen". The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume II: The Burial Chamber. By Carter, Howard. Duckworth. pp. 189–196. ISBN 978-0715630754.

- Price, Campbell (2016). "Other Tomb Goods". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 274–289. ISBN 978-0199931637.

- Reeves, Nicholas (1990). The Complete Tutankhamun. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500050583.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0500050804.

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2015). Contesting Antiquity in Egypt: Archaeologies, Museums & the Struggle for Identities from World War I to Nasser. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774169380.

- Ridley, Ronald T. (2019). Akhenaten: A Historian's View. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774167935.

- Riggs, Christina (2019). Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1350038516.

- Riggs, Christina (2021). Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1541701212.

- Ritner, Robert K. (1997). "The Cult of the Dead". In Silverman, David P. (ed.). Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 132–147. ISBN 978-0195219524.

- Roberson, Joshua A. (2016). "The Royal Funerary Books". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 316–332. ISBN 978-0199931637.

- Roehrig, Catharine H. (2016). "Royal Tombs of the Eighteenth Dynasty". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 183–199. ISBN 978-0199931637.

- Romer, John; Romer, Elizabeth (1993). The Rape of Tutankhamun. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 978-1854791696.

- Tawfik, Tarek; Thomas, Susanna; Hegenbarth-Reichardt, Ina (2018). "New Evidence for Tutankhamun's Parents: Revelations from the Grand Egyptian Museum". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Instituts für Ägyptische Altertumskunde in Kairo. 74.

- Thompson, Jason (2015). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology, 2. The Golden Age: 1881–1914. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774166921.

- Thompson, Jason (2018). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology, 3. From 1914 to the Twenty-First Century. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774167607.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2012). Tutankhamen: The Search for an Egyptian King. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465020201.

- Williamson, Jacquelyn (2015). "Amarna Period". In Wendrich, Willeke (ed.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Department of Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UC Los Angeles.

Further reading edit

- James, T. G. H. (2000). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun, Second Edition. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1860646157.

- Siliotti, Alberto (1996). Guide to the Valley of the Kings and to the Theban Necropolises and Temples. A. A. Gaddis. ISBN 978-9774247187.

- Winstone, H. V. F. (2006). Howard Carter and the Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, Revised Edition. Barzan Publishing. ISBN 978-1905521043.

External links edit

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation at the website of the Griffith Institute

- High-resolution image viewer of the tomb by Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation

- KV62: Tutankhamen at the Theban Mapping Project

- The Carter Centenary Gallery at the website of Swaffham Museum