Papillon (French: [papijɔ̃], lit. "butterfly") is a novel written by Henri Charrière, first published in France on 30 April 1969. Papillon is Charrière's nickname.[1] The novel details Papillon's purported incarceration and subsequent escape from the French penal colony of French Guiana, and covers a 14-year period between 1931 and 1945.

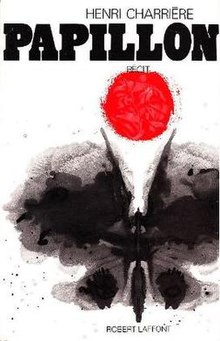

First edition (French) | |

| Author | Henri Charrière |

|---|---|

| Translator | Patrick O'Brian |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Autobiographical novel |

| Publisher | Robert Laffont (French) Hart-Davis, MacGibbon (English) |

Publication date | 1969 |

Published in English | January 1970 |

| Pages | 516 (French) |

| Followed by | Banco |

Synopsis edit

The book is an account of a 14-year period in Papillon's life (October 26, 1931 to October 18, 1945), beginning when he was wrongly convicted of murder in France and sentenced to a life of hard labor at the Bagne de Cayenne, the penal colony of Cayenne in French Guiana known as Devil's Island. He eventually escaped from the colony and settled in Venezuela, where he lived and prospered.

After a brief stay at a prison in Caen, Papillon was put aboard a vessel bound for South America, where he learned about the brutal life that prisoners endured at the prison colony. Violence and murders were common among the convicts. Men were attacked for many reasons, including money, which most kept in a charger (a hollow metal cylinder concealed in the rectum; also known as a plan d'evasion, plan, or "escape suppository").[2] Papillon befriended Louis Dega, a former banker convicted of counterfeiting. He agreed to protect Dega from attackers trying to get his charger.

Upon arriving at the penal colony, Papillon claimed to be ill and was sent to the infirmary. There he collaborated with two men, Clousiot and André Maturette, to escape from the prison. They planned to use a sailboat acquired with the help of the associated leper colony at Pigeon Island (Saint Lucia). The Maroni River carried them to the Atlantic Ocean, and they sailed to the northwest, reaching Trinidad.

In Trinidad the trio were joined by three other escapees; they were aided by a British family, the Dutch bishop of Curaçao, and several others. Nearing the Colombian coastline, the escapees were sighted. The wind died and they were captured and imprisoned again.

In Colombian prison, Papillon joined with another prisoner to escape. Some distance from the prison, the two went their separate ways. Papillon entered the Guajira peninsula, a region dominated by Amerindians. He was assimilated into a coastal village whose specialty was pearl diving. There he married two teenage sisters and impregnated both. After spending several months in relative paradise, Papillon decided to seek vengeance against those who had wronged him.

Soon after leaving the village, Papillon was captured and imprisoned at Santa Marta, then transferred to Barranquilla. There, he was reunited with Clousiot and Maturette. Papillon made numerous escape attempts from this prison, all of which failed. He was eventually extradited to French Guiana.

As punishment, Papillon was sentenced to two years of solitary confinement on Île Saint-Joseph (an island in the Îles du Salut group, 11 kilometers (7 miles) from the French Guiana coast). Clousiot and Maturette were given the same sentence. Upon his release, Papillon was transferred to Royal Island (also an island in the Îles du Salut group). An escape attempt was foiled by an informant (whom Papillon stabbed to death). Papillon had to endure another 19 months of solitary confinement. His original sentence of eight years was reduced after Papillon risked his life to save a girl caught in shark-infested waters.

After French Guiana officials decided to support the pro-Nazi Vichy Regime, the penalty for escape attempts was death, or capital punishment. Papillon decided to feign insanity in order to be sent to the asylum on Royal Island. Insane prisoners could not be sentenced to death for any reason, and the asylum was not as heavily guarded as Devil's Island. He collaborated on another escape attempt but it failed; the other prisoner drowned when their boat was destroyed against rocks. Papillon nearly died as well.

Papillon returned to the regular prisoner population on Royal Island after being "cured" of his mental illness. He asked to be transferred to Devil's Island, the smallest and considered the most "inescapable" island in the Îles de Salut group. Papillon studied the waters and discovered possibilities at a rocky inlet surrounded by a high cliff. He noticed that every seventh wave was large enough to carry a floating object far enough out into the sea that it would drift toward the mainland. He experimented by throwing sacks of coconuts into the inlet.

He found another prisoner to accompany him, a pirate named Sylvain. He had sailed in southeast Asia, where he was known to raid ships, killing everyone aboard for their money and goods. The two men jumped into the inlet, using sacks of coconuts for flotation. The seventh wave carried them out into the ocean. After days of drifting under the relentless sun, surviving on coconut pulp, they made landfall at the mainland. Sylvain sank in quicksand after having abandoned his coconut sack.

On the mainland, Papillon encountered Cuic Cuic, who had built a hut on an "island". The hut was set on solid ground surrounded by quicksand; Cuic Cuic depended on a pig to find the safe route over the quicksand. The men and the pig made their way to Georgetown, British Guiana, by boat. Papillon decided to continue to the northwest in the company of five other escapees. Reaching Venezuela, the men were captured and imprisoned at mobile detention camps in the vicinity of El Dorado, a small mining town near the Gran Sabana region. Surviving harsh conditions there, and finding diamonds, Papillon was eventually released. He gained Venezuelan citizenship and celebrity status a few years later.

The impact of Papillon edit

The book was an immediate sensation and bestseller, achieving widespread fame and critical acclaim. Upon publication it spent 21 weeks as number 1 bestseller in France, with more than 1.5 million copies sold in France alone. 239 editions of the book have since been published worldwide, in 21 different languages.[1]

The book was first published in France by Robert Laffont in 1969, and first published in Great Britain by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1970, with an English translation by Patrick O'Brian. The book was adapted for a Hollywood film of the same name in 1973, starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman, as well as another in 2017, starring Charlie Hunnam and Rami Malek. Charrière also published a sequel to Papillon, called Banco, in 1973.[citation needed]

Papillon has been described as "The greatest adventure story of all time" (Auguste Le Breton) and "A modern classic of courage and excitement" (Janet Flanner, The New Yorker).[citation needed]

Adaptations edit

- Papillon (1973), film directed by Franklin J. Schaffner

- Papillon (2017), film directed by Michael Noer, based on novels Papillon and Banco

- Italian comics artist Carlos Pedrazzini adapted Papillon into a comic book, published by El Tony.[3]

Editions edit

- ISBN 0-06-093479-4 (560 pages; English; paperback; published by Harper Perennial; July 1, 2001)

- ISBN 0-246-63987-3 (566 pages; English; hardcover; published by Hart-Davis Macgibbon Ltd; January, 1970)

- ISBN 0-85456-549-3 (250 pages; English; large-print hardcover; published by Ulverscroft Large Print; October, 1976)

- ISBN 0-613-49453-9 (English; school and library binding; published by Rebound by Sagebrush; August, 2001)

- ISBN 0-7366-0108-2 (English; audio cassette; published by Books on Tape, Inc.; March 1, 1978)

See also edit

- Rene Belbenoit, Devil's Island convict and author of Dry Guillotine, Fifteen Years Among The Living Dead (1938)

- Charles Brunier, Devil's Island convict with a butterfly tattoo, who in 2005 claimed to have been the inspiration for Papillon

- Clément Duval, Devil's Island escapee and memoirist whose story was also said to have inspired Papillon

References edit

- ^ a b "Charrière, Henri 1906-1973 [WorldCat.org]". Worldcat.org. Retrieved 2016-08-21.

- ^ "Plans, Plan d'evasion, Chargers, etc". Archived from the original on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ "Carlos Pedrazzini". Lambiek.net. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

External links edit

- James Erwin (former inmate) (December 4, 2006). "Among the ghosts". The Guardian.

- "The Fabulous Escapes of Papillon". Life. November 13, 1970. pp. 45–52. interview by Marie-Claude Wrenn

- "Devil's Island: Reform Comes At Last to France's Most Notorious Penal Colony". Life. July 12, 1939. pp. 65–71. A contemporary look at the then functioning "Devil's Island" during Henri's time there.

- "Henri Charrière - Papillon". Coopertoons.com Caricatures. Article which refutes some claims made by Charrière in the book.

- Articles published in O Rebate which deny Charrière's, account:

- Fries, Ronald (December 2, 2004). "Assunto: A farsa de um Papillon. (Macaé, ano I, Nº 49 - 5 a 12 de janeiro de 2007)". O Rebate (in Portuguese). Brazil. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012.

- "A GRANDE FARSA (Macaé, ano I, Nº 34 - 15)". O Rebate (in Portuguese). Brazil. September 22, 2006. Archived from the original on January 9, 2013.

- "A VERDADEIRA HISTÓRIA DE PAPILLON (Macaé, ano II, Nº 54 - 9 a 16 de fevereiro de 2007)". O Rebate (in Portuguese). Brazil. Archived from the original on January 22, 2008.