Juan Bautista Valentín Alvarado y Vallejo (February 14, 1809 – July 13, 1882)[1] usually known as Juan Bautista Alvarado, was a Californio politician that served as Governor of Alta California from 1837 to 1842.[2] Prior to his term as governor, Alvarado briefly led a movement for independence of Alta California from 1836 to 1837, in which he successfully deposed interim governor Nicolás Gutiérrez, declared independence, and created a new flag and constitution, before negotiating an agreement with the Mexican government resulting in his recognition as governor and the end of the independence movement.

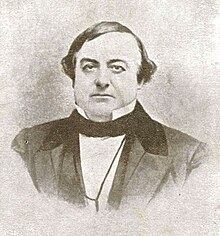

Juan Bautista Alvarado | |

|---|---|

| |

| 8th Governor of the Californias | |

| In office 1837–1842 | |

| Preceded by | Nicolás Gutiérrez |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Micheltorena |

| President of Alta California (Unrecognized) | |

| In office 1836–1837 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 14, 1809 Monterey, California |

| Died | July 13, 1882 (aged 73) San Pablo, California |

| Spouse | María Martina Castro de Alvarado |

| Profession | Politician, ranchero, rebel |

Early years edit

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

Alvarado was born in Monterey, Alta California, to Jose Francisco Alvarado and María Josefa Vallejo. His grandfather Juan Bautista Alvarado accompanied Gaspar de Portolà as an enlisted man in the Spanish Army in 1769. His father died a few months after his birth and his mother remarried three years later, leaving Juan Bautista in the care of his grandparents on the Vallejo side, where he and Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo grew up together. They were both taught by William Edward Petty Hartnell, an English merchant living in Monterey.

In 1827, eighteen-year-old Alvarado was hired as secretary to the territorial legislature. In 1829 he was briefly arrested along with Vallejo and José Castro by soldiers involved in the military revolt led by Joaquín Solis. In 1831 he built a house in Monterey for his mistress, Juliana Francisca Ramona y Castillo, whom he called "Raymunda", to live in. It's possible the home was for her sister, Maria Reymunda Castillo.[3] Over the years, the pair had at least two illegitimate daughters whom he recognized (Estefana del Rosario (born 1834),[4] and Maria Francisca de la Asencion (born 1836).[5] They may have had several more that he did not recognize, but they never married. During this period Alvarado began drinking heavily.

Supports secularization edit

Alvarado supported secularization of the Spanish missions in California. He was appointed by José María de Echeandía to oversee the turn over of Mission San Miguel, even though Echeandía was no longer governor. The new governor Manuel Victoria rescinded the order and sought to have Alvarado and Castro arrested. The pair fled and were hidden by their old friend Vallejo, who had become adjutant at the Presidio of San Francisco. However, Victoria was unpopular and Echeandía overthrew his rule and replaced him with Pío de Jesús Pico near the end of 1831.[6] Secularization of the missions resumed in 1833.

In 1834 Alvarado was elected to the legislature as a delegate and appointed customs inspector in Monterey. Governor José Figueroa granted Rancho El Sur, two square leagues of land, or about 9,000 acres (3,600 ha), south of Monterey, to Alvarado on October 30, 1834.

Independence movement edit

After Figueroa's death in September 1835, Nicolás Gutiérrez was appointed as interim governor in January 1836. He was replaced by Mariano Chico in April, but Chico was unpopular. His intelligence agents told him that another Californio revolt was brewing, hence he fled to Mexico, claiming he planned to gather troops against the independent Californios. Instead, Mexico reprimanded him for abandoning his post. Gutierrez, the military commandant, re-assumed the governorship, but like the Mexican governors before him, the Californios forced him to flee.[5] As senior members of the legislature, Alvarado and Castro, with political support from Vallejo and backing from a group of Tennesseans led by Capt. Isaac Graham, staged a revolt in November 1836 and forced Gutierrez out of the country. Alvarado's Californio coup wrote a constitution and adopted a new flag—a single red star on a white background, but neither were used after Alvarado made peace with Mexico.

Governor Alvarado edit

Alvarado, at age 27, was then appointed governor, but the city council of Los Angeles protested. Alvarado, Castro, and Graham went south and negotiated a compromise after three months, avoiding a civil war.[6] However, the city council of San Diego then voiced its disagreement with Alvarado's revolt. This time, the Mexican government was involved and there were rumors that the Mexican Army was ready to step in. Alvarado was able to negotiate another compromise to keep the peace.

Mexico reneged on the agreement, however, and appointed Carlos Antonio Carrillo, who was very popular among the southerners, governor on December 6, 1837. This time, civil war broke out and after several battles, Carrillo was forced out. Mexico finally relented and recognized Alvarado as governor.

Alvarado married Doña Martina Castro on August 24, 1839, in Santa Clara, but did not attend his own wedding having his half-brother, Jose Antonio Estrada, stand in for him. Though he claimed to be detained in Monterey on official business, it was rumored he was actually drunk and unable to function. After the wedding, Alvarado lived with his bride in Monterey, but continued on with mistress, Raymunda, who lived nearby.

The process of secularization of the missions was in its final stages, and it was at this time that Alvarado parceled out much of their land to prominent Californios via land grants. Though he took no land for himself, he did however, trade his Rancho El Sur to John B.R. Cooper in exchange for Rancho Bolsa del Potrero which he subsequently sold back to Cooper. He purchased Rancho El Alisal near Salinas in 1841 from his former tutor William Hartnell.

In April 1840 a report of a planned revolt against Alvarado by a group of foreigners, led by former ally Isaac Graham, caused the governor to order their arrest and deportation to Mexico City for trial. They were eventually, however, acquitted of all charges in June 1841. Also in 1841, political leaders in the United States were declaring their doctrine of Manifest Destiny, and Californios grew increasingly concerned over their intentions. Vallejo conferred with Castro and Alvarado recommending that Mexico send military reinforcements to enforce their military control of California.

Tensions between Northern and Southern California edit

In response, Mexican president Antonio López de Santa Anna sent Brigadier General Manuel Micheltorena and 300 men to California in January 1842. Micheltorena was to assume the governorship and the position of commandant general. In October, before Micheltorena reached Monterey, American Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones mistakenly thought that war had broken out between the US and Mexico. He sailed into Monterey Bay and demanded the surrender of the Presidio of Monterey. Micheltorena's force was still in the south and the Monterey presidio was undermanned. Alvarado reluctantly surrendered, and retired to Rancho El Alisal. The next day Commodore Jones learned of his mistake, but Alvarado declined to return and instead referred the commodore to Micheltorena.

Micheltorena eventually made it to Monterey, but was unable to control his troops, a number of which were convicts. This fomented rumors of a revolt, and by 1844, Alvarado became associated with the malcontents and an order was made by Micheltorena for his arrest. His detention was short-lived, as Micheltorena was under orders to organize a large contingent in preparation for war against the US. All hands would be required for the task.

This turned out to backfire on him, as on November 14, 1844, a group of Californios led by Manuel Castro revolted against Mexican authority. José Castro and Alvarado commanded the troops. Castro's drummer Juan 'Tambor' Higuera was killed during the capture of the barracks in Los Angeles, possibly the only Californio killed.[7] A truce was negotiated and Micheltorena agreed to dismiss his convict troops. Micheltorena later reneged on the deal and fighting broke out this time. The rebels won the Battle of Providencia in February 1845 at the Los Angeles River and Micheltorena and his troops left California.

Pío Pico was installed as governor in Los Angeles and José Castro became commandant general. Later, Alvarado was elected to the Mexican Congress. He prepared to move to Mexico City, but Pico declined funding for the transfer, and relations between northern and southern California deteriorated further.

John C. Frémont arrived in Monterey at the beginning of 1846. Afraid of foreign aggression, Castro assembled his militia, with Alvarado second in command, but Frémont went north to Oregon instead. An unstable political situation in Mexico strained relations among the Californios and it seemed that civil war would break out between north and south.

American conquest of California and later life edit

On July 7, Commodore John D. Sloat occupied Monterey, declaring to the citizenry that the Mexican–American War had begun. Pico, Castro, and Alvarado set aside their differences to focus on the American threat, but by the end of August, Pico and Castro fled to Mexico, and Alvarado was captured. Following his release, Alvarado spent the remainder of the war on his estate in Monterey.

After the war, Alvarado was offered the governorship but declined, instead retiring to his wife Martina's family estate at Rancho San Pablo in 1848.[8] Alvarado did not participate in the California Gold Rush, instead concentrating his efforts on agriculture and business. He opened the Union Hotel on the rancho in 1860, but his businesses were mostly unsuccessful. After Martina's death in 1876, Alvarado wrote his Historia de California.[9] He died on his ranch in 1882 and is buried at Saint Mary Cemetery in Oakland.

Alvarado's adobe house, at the foot of Alvarado Street in downtown Monterey, survives as a California Historical Landmark. The former settlement of Alvarado (now part of Union City) was named after him, as was Alvarado Street in San Francisco's Noe Valley. Portions of the Rancho San Pablo adobe are incorporated into the current City of San Pablo government campus and Alvarado Park within Wildcat Canyon Regional Park is named in his honor.

California Historical Landmark edit

The Governor Alvarado House is California Historical Landmark number #348.

California Historical Landmark reads:

- NO. 348 HOUSE OF GOVERNOR ALVARADO - A native of Monterey, Alvarado served as Governor of Mexican California from December 20, 1836 to December 20, 1842. During his administration the increasing influx of Americans and the Russian settlement at Fort Ross began to be regarded as serious problems.[10]

The adobe house, which is now occupied by a local bank branch, was seriously damaged in January, 2023, during the 2022–2023 California floods.[11]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "Governor Juan Alvarado". City of San Pablo. Archived from the original on 2017-02-01. Retrieved October 18, 2017.,

- ^ Juan Alvarado, Governor of California, 1836-1842

- ^ San Carlos Borromeo Baptism #02872 Archived 2020-12-13 at the Wayback Machine Huntington Library Early California Population Project, requires log-in

- ^ San Carlos Borromeo Baptism #0398 Archived 2022-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Huntington Library Early California Population Project, requires log-in

- ^ a b San Carlos Borromeo Baptism #4004 Archived 2023-05-28 at the Wayback Machine Huntington Library Early California Population Project, requires log-in

- ^ a b Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). History of California: 1825-1840. A.L. Bancroft. p. 478.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe; Oak, Henry Lebbeus; Nemos, William; Victor, Frances Fuller (1890). History of California: 1841-1845. History Company. p. 492.

- ^ A. F. Bray (1936-12-12). "Rancho San Pablo". Contra Costa Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ Alvarado, Juan Bautista (1 January 1876). Historia de California. OCLC 26239566.

- ^ californiahistoricallandmarks.com Landmarks chl-348

- ^ Dowd, Katie (January 15, 2023). "Historic 1830s Monterey home crumbles as storms batter California". SFGate. San Francisco. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

Sources edit

- "Juan Alvarado - Biographic Notes". Inn-California. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- Robert Ryal Miller (January 1999). Juan Alvarado: Governor of California, 1836-1842. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3101-6.

- Maud Adamson (1931). The Land Grant System of Governor Juan B. Alvarado. Department of History, University of Southern California.