Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland

The Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution Act 1995 (previously bill no. 15 of 1995) is an amendment of the Constitution of Ireland which removed the constitutional prohibition on divorce, and allowed for the dissolution of a marriage provided specified conditions were satisfied. It was approved by referendum on 24 November 1995 and signed into law on 17 June 1996.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

To remove the constitutional prohibition on divorce | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

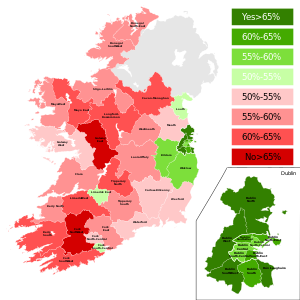

Results by Dáil constituency | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

editThe Constitution of Ireland adopted in 1937 included a ban on divorce. An attempt by the Fine Gael–Labour Party government in 1986 to amend this provision was rejected in a referendum by 63.5% to 36.5%.

In 1989, the Dail passed the Judicial Separation and Family Law Reform Act, which allowed Irish courts to recognize legal separation. The government made other legislative changes to address the issues identified in that referendum campaign, including the social welfare and pension rights of divorced spouses, which were copper fastened, and the abolition of the status of illegitimacy to remove any distinction between the rights of the children of first and subsequent unions.[1]

Shortly before its collapse, the 1989–1992 government published a white paper on marriage breakdown, which proposed "to have a referendum on divorce after a full debate on the complex issues involved and following the enactment of other legislative proposals in the area of family law".[2]

In 1995, the Fine Gael–Labour Party–Democratic Left government of John Bruton proposed a new amendment to allow for divorce in specified circumstances.

Changes to the text

editThe Fifteenth Amendment deleted the following Article 41.3.2° of the Constitution:

2° No law shall be enacted providing for the grant of a dissolution of marriage.

and substituted that subsection with the following:

2° A Court designated by law may grant a dissolution of marriage where, but only where, it is satisfied that –

- i. at the date of the institution of the proceedings, the spouses have lived apart from one another for a period of, or periods amounting to, at least four years during the previous five years,

- ii. there is no reasonable prospect of a reconciliation between the spouses,

- iii. such provision as the Court considers proper having regard to the circumstances exists or will be made for the spouses, any children of either or both of them and any other person prescribed by law, and

- iv. any further conditions prescribed by law are complied with.

Oireachtas Debate

editThe Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution (No. 2) Bill 1995 was proposed in the Dáil on 27 October 1995 by Minister for Equality and Law Reform Mervyn Taylor.[3] An amendment was proposed by Helen Keogh on behalf of the Progressive Democrats which would have allowed for legislation generally, without the restrictions proposed in the government's proposal:

2° Notwithstanding any other provision of this Constitution, a Court designated by law may grant a dissolution of marriage where it is satisfied that all the conditions prescribed by law are complied with.

This amendment was rejected and the Bill passed final stages by the Dáil without division on 11 October.[4] It was passed by the Seanad on 18 October and proceed to a referendum on 24 November 1995.[5]

Campaign

editThe Catholic Church was strongly against the amendment, but stated that Catholics could vote for the amendment in good conscience, and that it would not be a sin to do so.[6]

In the run-up to the vote the No Campaign used the now-infamous [7][8] slogan "Hello Divorce, Bye Bye Daddy" [9] which was criticised for being manipulative and irresponsible.

Justin Barrett was the spokesman for the Youth Against Divorce campaign. In later years, Barrett himself sought a divorce in 2016.[10]

Result

edit| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 818,842 | 50.28 |

| No | 809,728 | 49.72 |

| Valid votes | 1,628,570 | 99.67 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 5,372 | 0.33 |

| Total votes | 1,633,942 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 2,628,834 | 62.15 |

| Referendum results (excluding invalid votes) | |

|---|---|

| Yes 818,842 (50.3%) |

No 809,728 (49.7%) |

| ▲ 50% | |

| Constituency | Electorate | Turnout (%) | Votes | Proportion of votes | ± Yes 1986 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Carlow–Kilkenny | 84,365 | 64.2% | 24,651 | 29,283 | 45.7% | 54.3% | +13.9% |

| Cavan–Monaghan | 80,970 | 59.1% | 17,817 | 29,787 | 37.4% | 62.6% | +10.0% |

| Clare | 67,829 | 59.4% | 17,576 | 22,577 | 43.8% | 56.2% | +12.2% |

| Cork East | 60,995 | 65.8% | 17,287 | 22,748 | 43.2% | 56.8% | +13.7% |

| Cork North-Central | 69,936 | 61.9% | 20,110 | 23,050 | 46.6% | 53.4% | +16.1% |

| Cork North-West | 45,938 | 67.0% | 10,409 | 20,264 | 33.9% | 66.1% | +13.0% |

| Cork South-Central | 79,270 | 68.0% | 28,433 | 25,360 | 52.9% | 47.1% | +15.3% |

| Cork South-West | 46,046 | 64.9% | 11,755 | 18,034 | 39.5% | 60.5% | +12.6% |

| Donegal North-East | 49,473 | 51.9% | 10,401 | 15,219 | 40.6% | 59.4% | +14.0% |

| Donegal South-West | 50,208 | 51.1% | 10,450 | 15,109 | 40.9% | 59.1% | +10.7% |

| Dublin Central | 59,215 | 57.3% | 19,378 | 14,474 | 57.2% | 42.8% | +18.1% |

| Dublin North | 68,512 | 66.5% | 29,704 | 15,756 | 65.3% | 34.7% | +14.7% |

| Dublin North-Central | 64,070 | 69.0% | 25,721 | 18,415 | 58.3% | 41.7% | +14.3% |

| Dublin North-East | 58,595 | 66.9% | 25,360 | 13,714 | 64.9% | 35.1% | +13.9% |

| Dublin North-West | 56,469 | 63.2% | 21,628 | 13,942 | 60.8% | 39.2% | +13.2% |

| Dublin South | 87,565 | 70.0% | 39,454 | 21,723 | 64.5% | 35.5% | +10.1% |

| Dublin South-Central | 60,825 | 64.3% | 22,839 | 16,131 | 58.6% | 41.4% | +13.1% |

| Dublin South-East | 63,830 | 60.3% | 24,901 | 13,493 | 64.9% | 35.1% | +11.1% |

| Dublin South-West | 73,109 | 61.0% | 29,767 | 14,769 | 66.8% | 33.2% | +13.3% |

| Dublin West | 63,487 | 62.4% | 25,811 | 13,697 | 65.3% | 34.7% | +16.5% |

| Dún Laoghaire | 89,160 | 67.6% | 41,028 | 19,121 | 68.2% | 31.8% | +9.4% |

| Galway East | 43,768 | 59.0% | 9,003 | 16,730 | 35.0% | 65.0% | +11.8% |

| Galway West | 83,513 | 56.8% | 22,977 | 24,261 | 48.6% | 51.4% | +11.7% |

| Kerry North | 49,762 | 58.5% | 11,848 | 17,131 | 40.9% | 59.1% | +13.9% |

| Kerry South | 45,849 | 58.4% | 10,203 | 16,456 | 38.3% | 61.7% | +14.2% |

| Kildare | 82,825 | 61.7% | 29,397 | 21,592 | 57.7% | 42.3% | +12.7% |

| Laois–Offaly | 81,078 | 63.0% | 20,426 | 30,467 | 40.1% | 59.9% | +13.5% |

| Limerick East | 73,956 | 62.9% | 23,184 | 23,140 | 50.0% | 50.0% | +14.9% |

| Limerick West | 46,069 | 62.7% | 10,617 | 18,159 | 36.9% | 63.1% | +12.0% |

| Longford–Roscommon | 61,920 | 61.3% | 13,333 | 24,477 | 35.3% | 64.7% | |

| Louth | 68,809 | 62.0% | 22,004 | 20,516 | 51.7% | 48.3% | +15.9% |

| Mayo East | 44,366 | 56.3% | 9,243 | 15,621 | 37.2% | 62.8% | +12.9% |

| Mayo West | 45,745 | 55.3% | 10,455 | 14,764 | 41.5% | 58.5% | +15.1% |

| Meath | 83,655 | 59.6% | 23,790 | 25,861 | 47.9% | 52.1% | +16.2% |

| Sligo–Leitrim | 62,116 | 59.0% | 15,034 | 21,490 | 41.2% | 58.8% | +11.7% |

| Tipperary North | 43,958 | 65.6% | 11,020 | 17,699 | 38.4% | 61.6% | +12.8% |

| Tipperary South | 58,502 | 64.1% | 15,798 | 21,557 | 42.3% | 57.7% | +15.1% |

| Waterford | 66,132 | 62.0% | 20,305 | 20,508 | 49.8% | 50.2% | +16.7% |

| Westmeath | 46,900 | 60.1% | 11,704 | 16,353 | 41.7% | 58.3% | |

| Wexford | 79,445 | 62.1% | 23,850 | 25,305 | 48.5% | 51.5% | +17.8% |

| Wicklow | 80,599 | 63.7% | 30,171 | 20,975 | 59.0% | 41.0% | +12.1% |

| Total | 2,628,834 | 62.2% | 818,842 | 809,728 | 50.3% | 49.7% | +13.8% |

The '± Yes 1986' column shows the percentage point change in the Yes vote compared to the Tenth Amendment of the Constitution Bill on a similar proposal rejected in a referendum in 1986.

Court challenge

editDuring the referendum, government funds were used to advertise in favour of a 'Yes' vote. One week before the referendum, Patricia McKenna, a Green Party MEP, successfully lodged a complaint against the government with the Supreme Court, and the advertising stopped.[1] This Supreme Court decision led to legislation that would establish a Referendum Commission for each referendum, commencing with the Eighteenth Amendment in 1998.

The returning officer submitted a provisional certificate of the result of the referendum in the High Court as required by the Referendum Act 1994.[12][13]

According to The Irish Times, "the polls taken at the time showed that, if anything, the end of the advertising campaign coincided with a halt in the slide of support for divorce".[13] Because of the use of Government funds for one side of the campaign, a petition against the result was lodged by Des Hanafin, a Fianna Fáil Senator and chairman of the Pro Life Campaign, which was dismissed by the High Court on 9 February 1996.[13][1] Hanafin appealed to the Supreme Court, which in June upheld the High Court decision. The High Court then endorsed the provisional certificate on 14 June 1996.[13] President Mary Robinson signed the amendment bill into law three days later.

Subsequent legislation

editBefore the referendum, a draft Family Law (Divorce) Bill was published to illustrate how the Constitutional provisions would be implemented if the amendment were passed. Once the Constitutional amendment came into force, the divorce bill was introduced in the Oireachtas on 27 June 1996[14] and signed into law on 27 November 1996.[15] This gave effect in primary legislation to the new Constitutional provisions. Although this act, the Family Law (Divorce) Act, 1996, specified its own commencement date as 27 February 1997,[16] the first divorce was granted on 17 January 1997, based solely on the constitutional amendment, to a dying man who wanted urgently to marry his new partner.[17]

The Thirty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland was approved in a referendum held in May 2019, and removed the constitutional requirement for parties to be living apart before a divorce. It also altered the provisions in Article 41.3.3° on the recognition of foreign divorce.

References

edit- ^ a b c Coulter, Carol (13 June 1996). "Ten year wait is finally over for those who campaigned for divorce". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ Department of Justice (1 October 1992). Marital breakdown: a review and proposed changes (PDF). Official publications. Vol. Pl.9104. Dublin: Stationery Office. p. 9, §1.6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution (No. 2) Bill, 1995: Second Stage". Houses of the Oireachtas. 27 October 1995. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution (No. 2) Bill, 1995: Fifth Stage". Houses of the Oireachtas. 11 October 1995. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Fifteenth Amendment of the Constitution (No. 2) Bill, 1995: Committee and Final Stages". Houses of the Oireachtas. 11 October 1995. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Premier Urges Irish to Vote For Legalizing Of Divorce". New York Times. 20 November 1995. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Solicitors, Monahan (29 November 2016). "Hello Divorce, Bye Bye Daddy". Michael Monahan Solicitor.

- ^ Kenny, Aisling (6 May 2019). "Divorce in Ireland - A controversial history". RTÉ News.

- ^ Buchanan, Maryjane (27 June 2010). ""Hello Divorce….. Bye Bye Daddy…." Poster -1995 Divorce Referendum".

- ^ Coyle, Colin (7 May 2017). "Barrett denies hypocrisy over divorce U-turn". The Sunday Times.(subscription required)

- ^ a b "Referendum Results 1937–2015" (PDF). Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government. 23 August 2016. p. 52. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ "Referendum Act, 1994, Section 40". Irish Statute Book. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d Newman, Christine (15 June 1996). "Result of divorce referendum is formally signed by High Court". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ "Family Law (Divorce) Bill, 1996: Second Stage". Dáil Éireann debates. 27 June 1996. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Family Law (Divorce) Act, 1996". Irish Statute Book. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ^ "Family Law (Divorce) Act, 1996, Section 1". Irish Statute Book. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Shannon, Geoffrey (2011). "Judicial Separation and Divorce; 4.3.5. Case Law". Family Law. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780199589067. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

Further reading

edit- Department of Justice (1992). Marital breakdown : a review and proposed changes (PDF). Official publications. Vol. Pl.9104. Dublin: Stationery Office. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Department of Equality and Law Reform (September 1995). The right to remarry : a Government information paper on the divorce referendum (PDF). Official publications. Vol. Pn.1932. Dublin: Stationery Office. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Ad-hoc Commission on Referendum Information (October 1995). "Proposed constitutional amendment in relation to divorce : report" (PDF). Dublin. Retrieved 12 May 2017.