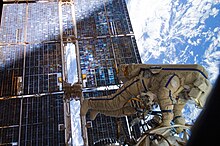

Extravehicular activity (EVA) is any activity done by an astronaut in outer space outside a spacecraft. In the absence of a breathable Earthlike atmosphere, the astronaut is completely reliant on a space suit for environmental support. EVA includes spacewalks and lunar or planetary surface exploration (commonly known from 1969 to 1972 as moonwalks). In a stand-up EVA (SEVA), an astronaut stands through an open hatch but does not fully leave the spacecraft.[1] EVAs have been conducted by the Soviet Union/Russia, the United States, Canada, the European Space Agency and China.

On March 18, 1965, Alexei Leonov became the first human to perform a spacewalk, exiting the Voskhod 2 capsule for 12 minutes and 9 seconds. On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong became the first human to perform a moonwalk, outside his lunar lander on Apollo 11 for 2 hours and 31 minutes. In 1984, Svetlana Savitskaya became the first woman to perform a spacewalk, conducting EVA outside the Salyut 7 space station for 3 hours and 35 minutes. On the last three Moon missions, astronauts also performed deep-space EVAs on the return to Earth, to retrieve film canisters from the outside of the spacecraft. American Astronauts Pete Conrad, Joseph Kerwin, and Paul Weitz also used EVA in 1973 to repair launch damage to Skylab, the United States' first space station.

EVAs may be either tethered (the astronaut is connected to the spacecraft; oxygen and electrical power can be supplied through an umbilical cable; no propulsion is needed to return to the spacecraft), or untethered. Untethered spacewalks were only performed on three missions in 1984 using the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU), and on a flight test in 1994 of the Simplified Aid For EVA Rescue (SAFER), a safety device worn on tethered U.S. EVAs.

Development history

editNASA planners invented the term extravehicular activity (abbreviated with the acronym EVA) in the early 1960s for the Apollo program to land humans on the Moon, because the astronauts would leave the spacecraft to collect lunar material samples and deploy scientific experiments. To support this, and other Apollo objectives, the Gemini program was spun off to develop the capability for astronauts to work outside a two-person Earth orbiting spacecraft. However, the Soviet Union was fiercely competitive in holding the early lead it had gained in crewed spaceflight, so the Soviet Communist Party, led by Nikita Khrushchev, ordered the conversion of its single-pilot Vostok capsule into a two- or three-person craft named Voskhod, in order to compete with Gemini and Apollo.[2] The Soviets were able to launch two Voskhod capsules before U.S. was able to launch its first crewed Gemini.

The Voskhod's avionics required cooling by cabin air to prevent any kind of overheating, therefore an airlock was required for the spacewalking cosmonaut to exit and re-enter the cabin while it remained pressurized. Unusually, and by contrast, the Gemini avionics did not require air cooling, allowing the spacewalking astronaut to exit and re-enter the depressurized cabin through an open hatch. Because of this, the American and Soviet space programs developed different definitions for the duration of an EVA. The Soviet (now Russian) definition begins when the outer airlock hatch is open and the cosmonaut is in vacuum. An American EVA began when the astronaut had at least their head outside the spacecraft.[3] The USA has changed its EVA definition since.[4][5]

First instance

editThe first EVA was performed on March 18, 1965, by Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, who spent 12 minutes and 9 seconds outside the Voskhod 2 spacecraft. Carrying a white metal backpack containing 45 minutes' worth of breathing and pressurization oxygen, Leonov had no means to control his motion other than pulling on his 15.35 m (50.4 ft) tether. After the flight, he claimed this was easy, but his space suit ballooned from its internal pressure against the vacuum of space, stiffening so much that he could not activate the shutter on his chest-mounted camera.[6]

At the end of his space walk, the suit stiffening caused a more serious problem: Leonov had to re-enter the capsule through the inflatable cloth airlock, 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) in diameter and 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) long. He improperly entered the airlock head-first and got stuck sideways. He could not get back in without reducing the pressure in his suit, risking "the bends". This added another 12 minutes to his time in vacuum, and he was overheated by 1.8 °C (3.2 °F) from the exertion. It would be almost four years before the Soviets tried another EVA. They misrepresented to the press how difficult Leonov found it to work in weightlessness and concealed the problems encountered until after the end of the Cold War.[6][7]

Project Gemini

editThe first American spacewalk was performed on June 3, 1965, by Ed White from the second crewed Gemini flight, Gemini IV, for 21 minutes. White was tethered to the spacecraft, and his oxygen was supplied through a 25-foot (7.6 m) umbilical, which also carried communications and biomedical instrumentation. He was the first to control his motion in space with a Hand-Held Maneuvering Unit, which worked well but only carried enough propellant for 20 seconds. White found his tether useful for limiting his distance from the spacecraft but difficult to use for moving around, contrary to Leonov's claim.[6] However, a defect in the capsule's hatch latching mechanism caused difficulties opening and closing the hatch, which delayed the start of the EVA and put White and his crewmate at risk of not getting back to Earth alive.[8]

No EVAs were planned on the next three Gemini flights. The next EVA was planned to be made by David Scott on Gemini VIII, but that mission had to be aborted due to a critical spacecraft malfunction before the EVA could be conducted. Astronauts on the next three Gemini flights (Eugene Cernan, Michael Collins, and Richard Gordon), performed several EVAs, but none was able to successfully work for long periods outside the spacecraft without tiring and overheating. Cernan attempted but failed to test an Air Force Astronaut Maneuvering Unit which included a self-contained oxygen system.

On November 13, 1966, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin became the first to successfully work in space without tiring during Gemini XII, the last Gemini mission. Aldrin worked outside the spacecraft for 2 hours and 6 minutes, in addition to two stand-up EVAs in the spacecraft hatch for an additional 3 hours and 24 minutes. Aldrin's interest in scuba diving inspired the use of underwater EVA training to simulate weightlessness, which has been used ever since to allow astronauts to practice techniques of avoiding wasted muscle energy.

First crew transfer

editOn January 16, 1969, Soviet cosmonauts Aleksei Yeliseyev and Yevgeny Khrunov transferred from Soyuz 5 to Soyuz 4, which were docked together. This was the second Soviet EVA, and it would be almost another nine years before the Soviets performed their third.[6]

Apollo missions

editAmerican astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin performed the first EVA on the lunar surface on July 21, 1969 (UTC), after landing their Apollo 11 Lunar Module spacecraft. This first Moon walk, using self-contained portable life support systems, lasted 2 hours and 36 minutes. A total of fifteen Moon walks were performed among six Apollo crews, including Charles "Pete" Conrad, Alan Bean, Alan Shepard, Edgar Mitchell, David Scott, James Irwin, John Young, Charles Duke, Eugene Cernan, and Harrison "Jack" Schmitt. Cernan was the last Apollo astronaut to step off the surface of the Moon.[6]

Apollo 15 command module pilot Al Worden made an EVA on August 5, 1971, on the return trip from the Moon, to retrieve a film and data recording canister from the service module. He was assisted by Lunar Module Pilot James Irwin standing up in the Command Module hatch. This procedure was repeated by Ken Mattingly and Charles Duke on Apollo 16, and by Ronald Evans and Harrison Schmitt on Apollo 17.[6]

Post-Apollo

editThe first EVA repairs of a spacecraft were made by Charles "Pete" Conrad, Joseph Kerwin, and Paul J. Weitz on May 26, June 7, and June 19, 1973, on the Skylab 2 mission. They rescued the functionality of the launch-damaged Skylab space station by freeing a stuck solar panel, deploying a solar heating shield, and freeing a stuck circuit breaker relay. The Skylab 2 crew made three EVAs, and a total of ten EVAs were made by the three Skylab crews.[6] They found that activities in weightlessness required about 21⁄2 times longer than on Earth because many astronauts suffered spacesickness early in their flights.[9]

After Skylab, no more EVAs were made by the United States until the advent of the Space Shuttle program in the early 1980s. In this period, the Soviets resumed EVAs, making four from the Salyut 6 and Salyut 7 space stations between December 20, 1977, and July 30, 1982.[6]

When the United States resumed EVAs on April 7, 1983, astronauts started using an Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) for self-contained life support independent of the spacecraft. STS-6 was the first Space Shuttle mission during which a spacewalk was conducted. Also, for the first time, American astronauts used an airlock to enter and exit the spacecraft like the Soviets. Accordingly, the American definition of EVA start time was redefined to when the astronaut switches the EMU to battery power.[10]

Numerous EVAs were conducted during the assembly of the ISS, often using the Quest Joint Airlock, designed to support both US EMUs, and Russian Orlan space suits.

By China

editChina became the third country to independently carry out an EVA on September 27, 2008, during the Shenzhou 7 mission. Chinese taikonaut Zhai Zhigang completed a 22-minute spacewalk wearing the Chinese-developed Feitian space suit, with taikonaut Liu Boming wearing the Russian-derived Orlan space suit assisting him in the process. Zhai completely exited the craft, while Liu stood by at the airlock, straddling the portal.

Since 2021, China has carried out several more extravehicular activities lasting several hours for the construction of the Tiangong space station.

By SpaceX

editAmerican company SpaceX conducted the first private sector-financed EVA on September 12, 2024. Entrepreneur Jared Isaacman and SpaceX engineer Sarah Gillis briefly ventured outside a Dragon capsule, for a stand-up EVA (SEVA) during the Polaris Dawn mission to conduct spacesuit mobility testing. [11] The other two crew members were exposed to the vacuum of space in the capsule, but did not leave it.[12] SpaceX plans to launch at least two more missions involving an EVA,[13] including one that involves SpaceX's still-in-development Starship launch vehicle.[14]

Milestones

editCapability milestones

edit- The first untethered spacewalk was made by American Bruce McCandless II on February 7, 1984, during the Space Shuttle Challenger mission STS-41-B, using the Manned Maneuvering Unit. He was subsequently joined by Robert L. Stewart during the 5-hour, 55-minute spacewalk. A self-contained spacewalk was first attempted by Eugene Cernan in 1966 on Gemini 9A, but Cernan could not reach the maneuvering unit without tiring.

- The first metalwork in open space, consisting of welding, brazing and metal spraying, was conducted by Soviet cosmonauts Svetlana Savitskaya and Vladimir Dzhanibekov on July 25, 1984. A specially designed multipurpose tool was used to perform these activities during a 3-hour, 30-minute EVA outside the Salyut 7 space station.[15][16][17]

- The first three-person EVA was performed on May 13, 1992, as the third EVA of STS-49, the maiden flight of Endeavour.[18] Pierre Thuot, Richard Hieb, and Thomas Akers conducted the EVA to hand-capture and repair a non-functional Intelsat VI-F3 satellite. As of 2021[update] it was the only three-person EVA.[19]

- The first EVA to perform an in-flight repair of the Space Shuttle was by American Steve Robinson on August 3, 2005, during "Return to Flight" mission STS-114. Robinson was sent to remove two protruding gap fillers from Discovery's heat shield, after engineers determined there was a small chance they could affect the shuttle upon re-entry. Robinson successfully removed the loose material while Discovery was docked to the International Space Station.

- The longest EVA performed as of December 2024, was 9 hours, performed by Cai Xuzhe and Song Lingdong on December 17, 2024.[20] The previous record was held by USA astronauts James Voss and Susan Helms, who made eight hours and 56 minutes EVA outside Space Shuttle Discovery on March 11, 2001.[21]

Personal cumulative duration records

edit- Russian Anatoly Solovyev holds both the record for most EVAs and for the greatest cumulative duration spent in EVA (16 EVAs; 82 hr and 22 min over 4 Mir missions between July 1990 and January 1998).

- Michael Lopez-Alegria holds the American record (10 EVAs; 67 hr and 40 min over 2 Shuttle and 1 ISS missions between October 2000 and February 2007).

- Thomas Pesquet holds the European (and non-US/Russian) record (6 EVAs; 39 hr and 54 min over 2 ISS missions between January 2017 and August 2021).[22]

- Peggy Whitson holds the record for most EVAs and most cumulative duration spent for a woman (10 EVAs, 60 hr and 21 min over 3 ISS missions between August 2002 and May 2017).

National, ethnic and gender firsts

edit- The first woman to perform an EVA was Soviet Svetlana Savitskaya on July 25, 1984, while aboard the Salyut 7 space station. Her EVA lasted 3 hours and 35 minutes.

- The first American woman to perform an EVA was on October 11, 1984, by Kathryn D. Sullivan during STS-41-G.

- The first two women to perform an EVA together and the first all-female EVA team were Christina Koch and Jessica Meir on October 18, 2019, during Expedition 61 on the International Space Station.[23][24][25]

- The first female Asian and Chinese woman to perform an EVA was Wang Yaping on 8 November 2021, outside the Chinese Tiangong space station.

- The first Native American woman to perform a space walk was Nicole Aunapu Mann on January 20, 2023, during Expedition 68 on the International Space Station.[26]

- The first EVA by a non-Soviet, non-American was made on December 9, 1988, by Jean-Loup Chrétien of France during a three-week stay on the Mir space station.

- The first EVA by a black African-American was on February 9, 1995, by Bernard A. Harris Jr during STS-63.

- The first EVA by a Japanese astronaut was made on November 25, 1997, by Takao Doi during STS-87.

- The first EVA by a Swiss astronaut was made on December 23, 1999, by Claude Nicollier during STS-103.

- The first EVA by an Australian-born person was on March 13, 2001, by Andy Thomas (although he is a naturalized US citizen).

- The first EVA by a Canadian astronaut was made on April 22, 2001, by Chris Hadfield along with NASA astronaut Scott Parazynski during mission STS-100 to install Canadarm2 on the International Space Station.[27]

- The first EVA by a Swedish astronaut was made on December 12, 2006, by Christer Fuglesang.

- The first EVA by a Chinese astronaut was made on September 27, 2008, by Zhai Zhigang during Shenzhou 7 mission. The spacewalk, using a Feitian space suit, made China the third country to independently carry out an EVA.

- The first EVA by an Italian astronaut was made on July 9, 2013, by Luca Parmitano along with NASA Astronaut Chris Cassidy during Expedition 36 on the International Space Station.

- The first EVA by a British astronaut was on January 15, 2016, by Tim Peake.[28]

- Although British-American Michael Foale carried out an EVA on February 9, 1995, he flew as an American astronaut in NASA's program.[28]

- The first EVA by an Arab astronaut was made on April 28, 2023, by Emirati astronaut Sultan Al Neyadi.[29]

Commemoration

editThe first spacewalk, made by Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, was commemorated in 1965 with several Eastern Bloc stamps (see Alexei Leonov#Stamps). Since the Soviet Union did not publish details of the Voskhod spacecraft at the time, the spaceship depiction in the stamps was purely fictional.

The U.S. Post Office issued a postage stamp in 1967 commemorating Ed White's first American spacewalk. The engraved image has an accurate depiction of the Gemini IV spacecraft and White's space suit.[30]

U.S.S.R. commemorative issue of 1965 |

U.S. Commemorative Issue of 1967 |

Designations

editNASA "spacewalkers" during the Space Shuttle program were designated as EV-1, EV-2, EV-3 and EV-4 (assigned to mission specialists for each mission, if applicable).[31][32]

Camp-out procedure

editFor EVAs from the International Space Station, NASA employed a camp-out procedure to reduce the risk of decompression sickness.[33] This was first tested by the Expedition 12 crew. During a camp-out, astronauts sleep overnight in the airlock prior to an EVA, lowering the air pressure to 10.2 psi (70 kPa), compared to the normal station pressure of 14.7 psi (101 kPa).[33] Spending a night at the lower air pressure helps flush nitrogen from the body, thereby preventing "the bends".[34][35] More recently astronauts have been using the In-Suit Light Exercise protocol rather than camp-out to prevent decompression sickness.[36][37]

See also

edit- List of longest spacewalks

- List of cumulative spacewalk records

- List of International Space Station spacewalks

- List of Tiangong space station spacewalks

- List of Mir spacewalks

- List of spacewalkers

- List of spacewalks since 2015

- List of spacewalks 2000–2014

- List of spacewalks and moonwalks 1965–1999

- Suitport

- The Age of Pioneers, 2017 film about the first spacewalk

References

edit- ^ NASA (2007). "Stand-Up EVA". NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2003a). Sputnik and the Soviet Space Challenge. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2627-X.

- ^ Walking to Olympus, p. ix.

- ^ Dasch, E. Julius (2018). O’Meara, Stephen James (ed.). A Dictionary of Space Exploration. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780191842764.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-184276-4.

- ^ "Extravehicular Activity". Man-Systems Integration Standards. Vol. one (Revised B ed.). NASA. 1995.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Portree, David S. F.; Treviño, Robert C. (October 1997). "Walking to Olympus: An EVA Chronology" (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History Series #7. NASA History Office. pp. 1–2. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ Rincon, Paul; Lachmann, Michael (October 13, 2014). "The First Spacewalk How the first human to take steps in outer space nearly didn't return to Earth". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Oral History Transcript / James A. McDivitt / Interviewed by Doug Ward / Elk Lake, Michigan – June 29, 1999.

- ^ Skylab Reuse Study, p. 3-53. Martin Marietta and Bendix for NASA, September 1978.

- ^ William Harwood (January 15, 2020). "Second all-female spacewalk devoted to space station battery replacements". CBS News. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Patel-Carstairs, Sunita (September 12, 2024). "SpaceX Polaris Dawn: Billionaire Jared Isaacman becomes first person to take part in private spacewalk". Sky News. Archived from the original on September 12, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ "SpaceX Polaris Dawn astronauts perform historic 1st private spacewalk in orbit (video)". space.com. September 12, 2024. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Goddard, Jacqui (September 12, 2024). "SpaceX's success redefines the commercial space frontier, but what's next?". The Times. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Davenport, Christian (September 12, 2024). "SpaceX Polaris astronauts complete first spacewalk by private citizens". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 12, 2024.

- ^ Mark Wade. "Encyclopedia Astronautica Salyut 7 EP-4". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "A pictorial history of welding as seen through the pages of the Welding Journal". American Welding Society. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Space welding anniversary". RuSpace.com. July 16, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ NASA (2001). "STS-49". NASA. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- ^ Facts about spacesuits and spacewalks (NASA.gov) Archived 2013-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huaxia (December 17, 2024). "Update: Shenzhou-19 crew completes first extravehicular activities". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved December 17, 2024.

- ^ Guinness World Records. "Longest spacewalk". Guinness World Records. Retrieved December 18, 2024.

- ^ "Thomas Pesquet - EVA experience". www.spacefacts.de. Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ "NASA Astronauts Spacewalk Outside the International Space Station on Oct. 18". NASA. October 18, 2019. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Voor het eerst maakt vrouwelijk duo ruimtewandeling bij ISS" [For the first time a female duo is taking a space walk at ISS]. nu.nl (in Dutch). October 18, 2019.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (October 18, 2019). "NASA TV is Live Now Broadcasting First All-Woman Spacewalk". NASA Blogs. NASA. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ "NASA astronaut becomes first Native American woman to conduct spacewalk". KRIS 6 News Corpus Christi. January 23, 2023.

- ^ "Spacewalks". www.asc-csa.gc.ca. June 17, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ a b Rincon, Paul (January 5, 2016). "Tim Peake on historic spacewalk". BBC News. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (April 28, 2023). "Watch live: First Arab spacewalker heads outside International Space Station – Spaceflight Now". Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Scotts Specialized Catalogue of United States Postage Stamps

- ^ "Extravehicular Activity Radiation Monitoring (EVARM)". NASA. October 1, 2001. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ^ "Extravehicular Activity Radiation Monitoring (EVARM)". Marshall Space Flight Center. October 1, 2001. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ^ a b NASA (2006). "Preflight Interview: Joe Tanner". NASA. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2008.

- ^ NASA. "International Space Station Status Report #06-7". NASA. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2006.

- ^ NASA. "Pass the S'mores Please! Station Crew 'Camps Out'". NASA. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2006.

- ^ NASA (February 26, 2015). "EVA Physiology". NASA. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Brady, Timothy K.; Polk, James D. (February 2011). "In-Suit Light Exercise (ISLE) Prebreathe Protocol Peer Review Assessment. Volume 1". NASA. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

External links

edit- NASA JSC Oral History Project Walking to Olympus: An EVA Chronology PDF document.

- Astronaut space walk picture

- NASDA Online Space Notes

- Apollo Extravehicular mobility unit. Volume 1: System description – 1971 (PDF document)

- Apollo Extravehicular mobility unit. Volume 2: Operational procedures – 1971 (PDF document)

- Skylab Extravehicular Activity Development Report – 1974 (PDF document)

- Analysis of the Space Shuttle Extravehicular Mobility Unit – 1986 (PDF document)

- NASA Space Shuttle EVA tools and equipment reference book – 1993 (PDF document)

- Preparing for an American EVA on the ISS – 2006