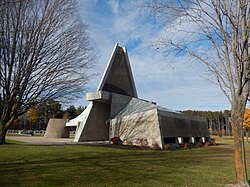

The Évêques-de-Trois-Rivières Mausoleum is a funerary monument in Trois-Rivières, Quebec. It was built in 1965 and 1996, as part of a renovation campaign at Assumption Cathedral aimed at replacing the crypt with a community room in the basement. It is located in the Saint-Michel cemetery, which was opened in the early 1920s. This modern monument, which includes a mausoleum with ten tombs and a funeral chapel, was built according to the designs of architects Jean-Claude Leclerc and Roger Villemure.

| Évêques-de-Trois-Rivières Mausoleum | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Mausoleum and Chapel |

| Architectural style | Expressionist architecture |

| Town or city | Trois-Rivières, Quebec. |

| Country | Canada |

| Coordinates | 46°21′09″N 72°34′30″W / 46.35250°N 72.57500°W |

| Year(s) built | 1965-1966 |

| Owner | Roman Catholic Diocese of Trois-Rivières |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Jean-Claude Leclerc, Roger Villemure |

| Awards and prizes | Listed heritage building (2007) Classified heritage building (2009) |

The building is infused with symbolism. The chapel evokes the ascension of souls, with its slender semi-cone shape. As for the mausoleum, its massive shape recalls the repose of bodies on Earth. It is one of the few mausoleums built in Quebec in the 20th century, and the only outdoor mausoleum reserved for religious figures.

It was listed as a heritage building by the City of Trois-Rivières in 2007 and classified as a heritage building in 2009 by the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications.

Location edit

The Evêques-de-Trois-Rivières mausoleum is located in the center of the Saint-Michel cemetery in Trois-Rivières.[1] Its installation here is no accident, for the 1962 cemetery plans by landscape architects Benoît Bégin and Georges Daudelin foresaw a chapel in this location. It is set in a large open space offering multiple views of the mausoleum across the cemetery. The main view remains the main axis of the cemetery from the entrance. Architect Jean-Claude Leclerc exploited this perspective by creating a gap in the monument, allowing the cemetery's calvary to be seen from the entrance.[2]

However, the mausoleum is barely visible from outside the cemetery and is not a landmark in the town.[2]

History edit

Context edit

The Trois-Rivières diocese was created in 1852, from a detachment of the Archdiocese of Quebec. It was separated at the same time as the diocese of Saint-Hyacinthe, in order to bring diocesans closer to Church administration. Assumption Cathedral was built between 1854 and 1858. The spire was added in 1882 and raised in 1904. The interior decoration was completed in 1895. In 1964, a major renovation program was carried out on the cathedral, overseen by architect Jean-Louis Caron. The wooden floor was replaced by a concrete one, and it was decided to build two community rooms in the basement.[3]

The land of the Saint-Michel cemetery was purchased in 1923 by the parish of Immaculée-Conception. At the time, it was located on Chemin de Forges, on the northern edge of town. It was four times larger than the cemetery it replaced, Saint-Louis Cemetery. Construction began in 1923, but was soon abandoned for lack of funds. However, the first bodies were interred in 1927. Work resumed in 1931, and the cemetery was officially inaugurated the following year. In 1962, it was decided to substantially redevelop the cemetery. The entrance was moved back from Boulevard des Forges, and plans were made to build a funeral chapel in the center of the cemetery. In 1968, a calvary with four bronze figures was added to the central axis of the cemetery.[4]

Construction edit

During the cathedral's renovation campaign, the question arose of where to bury the bodies currently in the crypt. Two choices were presented: either to build a new crypt in the basement, as had been done for the Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica in Quebec City, or to build a mausoleum in a new location. The second choice was quickly imposed by the desire to reclaim the cathedral's entire basement. As the redevelopment of the Saint-Michel cemetery called for the construction of a funeral chapel in its center, it was decided to include the mausoleum in the project.[4]

In 1964, the bishop's administration, under the supervision of Most Rev. Georges-Léon Pelletier, commissioned the first designs from architects Jean-Claude Leclerc and Roger Villemure. Although the latter had been in initial contact with the bishopric, it was his partner Leclerc who took charge of the project with his assistant, designer Victor Pinheiro. It was Pinheiro who drew up the first draft of the project, with two concrete walls. When the project was presented to the diocese, the concept of the voiles was maintained, but it was decided to give two distinct forms to the mausoleum and the chapel. The chapel would illustrate an impetus towards the sky, while the mausoleum would be a massive volume anchored to the ground. Leclerc describes it as follows:[5]

"[...] it will not be an ordinary building, but rather a central monument usable for three main purposes: bishops' tombs, interior and exterior religious ceremonies, and one of the stations of the Cross, all of which should be the center of gravity and set the tone and development of the heart of the cemetery."[5]

Plans for the mausoleum became more precise in early 1965, and specifications were drawn up in September 1965. General contractor Henri Saint-Amant won the contract for $76,000. The cost of the work included subcontracting Canada Gunite Co. Ltd for the construction of the concrete walls. The architects and probably the engineers offered their services without remuneration, a customary practice at the time for a project involving a diocese or factory. The reinforced concrete foundation was poured between October and November 1965, and work was halted for the winter. In March of the following year, work resumed with the installation of the concrete walls, and finishing work took place the following summer.[5]

In June and July 1966, the bodies were exhumed from the cathedral crypt. While the identification of the bishops' graves was easy, the other bodies were more difficult to identify. In the end, only five out of the 45 bodies buried since 1850 could be identified.[5] The bodies were moved and buried in the late summer of 1966. The bodies of the four bishops were placed in the funerary monument and the other remains in the surrounding area. The mausoleum was inaugurated that summer by Most Rev. Georges-Léon Pelletier.[6]

The building was designated a heritage building by the City of Trois-Rivières on September 17, 2007. Jean-Claude Leclerc and Paul Guay, abbot of the Évêché de Trois-Rivières, were interviewed the same year to establish a heritage evaluation file.[7][8] Two years later, on September 17, 2009, the Ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine classified the mausoleum as a heritage building.[9] It is one of three modern buildings to have been classified or cited during its designer's lifetime, along with the Maison Ernest-Cormier and Habitat 67.[8]

Architecture edit

The mausoleum is built entirely out of reinforced concrete. The roof is composed of a thin veil of reinforced concrete.[1] Its dimensions are 27.43 m long by 15.24 m wide, and 16.76 m high. The building consists of two parts: a 60-seat funeral chapel and a mausoleum containing ten tombs, five of which are occupied.[10]

The shape of the chapel is reminiscent of a skyward-facing sail. The nave faces the altar. The benches are made of wood and concrete and are set slightly below ground level. It has a small, rounded sacristy with a vertically striated concrete surface, a common technique in Brutalist architecture of the period. It also features a gargoyle. The gargoyle also supports the roof. The west and north sides are open to allow the chapel to receive more people, while the east side has only a small opening. The roof is made of a thin, rounded veil. A skylight installed at a 45° angle allows light to enter the chapel through the roof.[11]

The mausoleum, on the other hand, is considerably more spacious. It has two entrances, allowing a continuous flow of visitors during ceremonies. The gravestones are made of grey granite and are slightly inclined. They are lit by horizontal skylights at the top, which are fitted with randomly-arranged iron bars. An inscription, "Let eternal light shine on them", is placed just above the window wells. The roof, which is set much lower than the one on the chapel, is composed of two thin hyperbolic paraboloid sails supported by a central beam and the walls. Two gargoyles on each side of the monument keep rainwater away from the structure.[11]

Throughout the monument, concrete stripping marks are visible, sometimes painted, and sometimes left bare. The main walls are marked by conventional formwork lines, while the roof retains traces of the wooden planks used in the blown-cement construction method. The outer roof surface is coated with waterproofing membranes.[12]

A central beam is located in the middle of the monument between the chapel and the mausoleum. This beam, a cantilevered horizontal plane with no visible support, gives the impression of floating in mid-air. And the covered passageway it protects provides a visual breakthrough to the cemetery's calvary from the main entrance.[13]

The entire structure is imbued with symbolism and plays an important role in the architectural aspect of the monument. The chapel rises skyward, bathed in light. Its shape and numerous openings also evoke lightness. As for the mausoleum, its low volume and thick walls evoke massiveness. Its few openings create a penumbra atmosphere that evokes a sense of mournful reverence. The dichotomy of the whole (lightness and massiveness, light and shadow, openness and closure, momentum and restraint) evokes the metaphor of mind and body, and perfectly reflects the dual Christian symbolism of the soul's ascent after death and the body's entombment.[13]

Jean-Claude Leclerc's career as an architect only lasted from 1960 to 1972, but was nonetheless punctuated by several important works. He is generally regarded as the architect who introduced modernism to Trois-Rivières. With the exception of a few buildings, most of Jean-Claude Leclerc's work is located in the immediate Trois-Rivières area.[14]

The mausoleum has a special place in Leclerc's career. It is one of his most significant works, along with the Notre-Dame-du-Rosaire church in Fatima and the Trois-Rivières city hall. Although less imposing than his other two works, it fits nicely into Leclerc's Corbusian period, which began after he visited some of Le Corbusier's works and took part in André Wogenscky's studio. In the mausoleum, he incorporates a number of formal references from the Notre-Dame-du-Haut chapel and the Sainte-Marie de La Tourette convent, such as the massive walls, concrete sails, gargoyles, and other details.[15]

The monument did not enjoy great critical acclaim. Books on the architecture of the period, Architectures du xxe siècle au Québec by Claude Bergeron and Architecture contemporaine du Québec 1960-1970 by Laurent Lamy, make no mention of it. The review of this work comes from a Docomomo Québec newsletter published in 1994 and written by architect Daniel Durand. Durand discusses Trois-Rivières' major architectural works of the 1960s. He writes of the mausoleum: "the general form is not as finished as one might expect, given that it was designed by Leclerc and Pinheiro". He doesn't seem to have done much research, as he dates the construction to 1970.[16]

Buried personalities edit

Bishops edit

The Diocese of Trois-Rivières has had nine bishops since its creation in 1852. Three of these bishops are still living.[17] Out of the six bishops who have died to date, five are buried in the mausoleum; only Cardinal Maurice Roy is not.

First, Thomas Cooke was born in Pointe-du-Lac, Bas-Canada, in 1792. He studied at the Nicolet and Québec seminaries. He was ordained a priest in 1814. Beginning his ministry in Rivière-Ouelle. In 1817, he was transferred to Caraquet as a missionary priest. After building five churches, he was overcome by exhaustion and asked to be called back in 1822, which he was granted the following year. He was then given the ministry of Loretteville, along with the Wyandot Indian mission and the Valcartier Irish settlement. His reputation led the bishop of Québec in 1835 to appoint him parish priest of Trois-Rivières and Cap-de-la-Madeleine, as well as vicar general and member of the corporation of the Nicolet seminary. In 1852, he was appointed bishop of the new diocese of Trois-Rivières. His episcopate was marked above all by the development of the diocese and by financial difficulties. He was also responsible for the construction of the cathedral. He passed away in 1870.[18]

The second one, Louis-François Richer Laflèche, was born in 1818 in Sainte-Anne-de-la-Pérade. He began his studies in 1831 at the Nicolet Seminary and was ordained a priest in 1844. He left for Western Canada to found the Île-à-la-Crosse mission with Alexandre-Antonin Taché, evangelizing the Amerindians between 1846 and 1849. He then moved to Saint-Boniface, where he remained until 1856. He subsequently became a professor and then director of the Nicolet Seminary. Soon he came to the attention of Thomas Cooke, who, despite his protests, appointed him grand vicar in 1861 and coadjutor bishop in 1867. He attended the Vatican Council in 1869, where he regularly voted with the ultramontanes. The following year, he succeeded Cooke. Highly politicized, he was involved in issues as diverse as the creation of the Université de Montréal, which he supported. Some of the other bishops joined forces against him, forcing him to lose the territory of the Diocese of Nicolet after a ten-year struggle. He supported Taché and his successor Louis-Philippe-Adélard Langevin during the second Métis uprising, the hanging of Louis Riel, and the Manitoba Schools Question. He passed away in 1898.[19]

Next is François-Xavier Cloutier who was born in Sainte-Geneviève-de-Batiscan in 1848. He was ordained a priest in 1872. Founder of the École normale de jeunes filles de Trois-Rivières, he was named bishop upon the death of Most Rev. Laflèche in 1898. His episcopate was marked by the 1908 Trois-Rivières fire and the First World War. He died in 1934, the year of the city's tercentenary.[20]

In adittion we have Alfred-Odilon Comtois, who was born in Trois-Rivières in 1876. He was ordained a priest in 1898. In 1926, he became auxiliary bishop to Most Rev. Cloutier, succeeding him in 1934. He died in Saint-Mathieu in 1945.[21]

Lastly, Georges-Léon Pelletier, was born in Saint-Épiphane in 1904. He was ordained a priest in 1931 and became auxiliary bishop of Quebec City in 1943. He was appointed Bishop of Trois-Rivières in 1947 to replace Maurice Roy, who had been promoted to Archbishop of Quebec. His episcopate was marked by the diocese's centenary and the Marian congress at Cap-de-la-Madeleine in 1954. He also took part in the Second Vatican Council in 1962 and 1965. He handed over his duties to his successor, Laurent Noël, in 1975. He died in Trois-Rivières in 1987 and is buried in the mausoleum he had built.[21]

Others edit

In 1966, 45 bodies were exhumed from the crypt of the cathedral and buried on the outskirts of the mausoleum. These included the bodies of four prelates, nine priests, one friar, 26 laymen, and five unidentified bodies. Among the laity were a number of town's dignitaries, including seigneur Joseph-Michel Boucher de Niverville (1808-1870), his son Louis-Charles Boucher de Niverville (1825-1869), lawyer, mayor and deputy of Trois-Rivières, and judge Dominique Mondelet (1798-1863). The bodies of 22 other priests have been interred since the monument was built.[21]

The following is a list of the friar and priests transferred to the periphery of the mausoleum, arranged by chronology of death:[22]

- Abbot Télesphore Toupin, V.G., cathedral priest (1832-1864)

- Abbot Jean Bourque (1843-1865)

- Abbot Édouard Chabot, bishop's procurator (1818-1866)

- Abbot Gédéon Brunelle (1843-1874)

- Abbot Isodore Béland (1846-1877)

- Abbot Édouard Ling, Secretary to the Bishop (1845-1881)

- Abbot Onésime Landry (1850-1881)

- Abbot Ambroise Blais (1859-1883)

- Friar Omer de Jésus, F.E.C., born Hilaire Émond (1844-1884)

- Abbot Chs. Flavien Baillargeon (1833-1901)

- Most Rev. Louis Ricard, cathedral priest (1838-1908)

- Most Rev. Jean-Bte Comeau, V.G., cathedral priest (1841-1913)

- Most Rev. Ubald Marchand, P.A., vicar general (1863-1923)

- Most Rev. Jules Massicotte, P.D., cathedral priest (1871-1924)

The following is a list of priests buried on the outskirts of the mausoleum since its construction, arranged in chronological order of death:[23]

- Chanoine Hormidas Deschênes, priest of Saint-Philippe (1884-1967)

- Chanoine Joseph Desislets, priest of Sainte-Cécile (1887-1967)

- Chanoine Henri Garceau, seminary attorney (1889-1968)

- Chanoine Major Robert Giroux, bishop's procurator (1907-1970)

- Abbé Albert Dessureault, priest of Saint-Louis-de-France (1888-1971)

- Abbé Marcel-L. Desaulniers, professor at Trois-Rivières seminary (1902-1972)

- Abbé Jaromir Vochoc, chaplain at Saint-Joseph hospital in Trois-Rivières (1918-1977)

- Abbé Hector Marcotte, Trois-Rivières seminar (1881-1978)

- Abbé Henri J. Bourassa, chaplain J.O.C.F. (1906-1980)

- Chanoine Henri Moreau, priest of Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix (1896-1981)

- Abbé Gilles Poisson, pastoral school coordinator (1927-1981)

- Abbé Lucien Gélinas, priest of Saint-Eugène (1902-1984)

- Abbé Mastaï Chicoyne, priest of Saint-Prosper et de Saint-Michel des Forges (1890-1985)

- Abbé Charles-Édouard Coutu, chaplain of the Ursulines monastery (1914-1986)

- Abbé Florent Piette, priest of Saint-Jean-Baptiste-de-la-Salle (1921-1988)

- Abbé André Levasseur, priest of Saint-Georges de Champlain (1909-1991)

- Abbé Armand Julien, professor at Saint-Joseph seminary (1924-1996)

- Abbé Paul-Henri Carignan, chaplain at Daughters of Jesus (1910-1996)

- Abbé Léo Girard, chaplain and priest (1917-2002)

- Abbé Marcel Marchand, priest of Saint-Sévère (1913-2003)

- Roland Leclerc, Faith Communicator (1946-2003)

- Abbé Yves Dostaler, professor at Saint-Joseph seminary, founder priest of the Jean-XXIII parish (1924-2003)

References edit

- ^ a b "Mausolée des Évêques-de-Trois-Rivières" archive, on Lieux patrimoniaux du Canada (accessed October 30th, 2012)

- ^ a b Patri-Arch 2007, p. 81

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 7-8

- ^ a b Patri-Arch 2007, p. 43-44

- ^ a b c d Patri-Arch 2007, p. 10

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 13

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 4

- ^ a b Vanlaethem 2012, p. 9

- ^ Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, "Mausolée des Évêques-de-Trois-Rivières" archive, on Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec (accessed February 10th, 2013)

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 6

- ^ a b Patri-Arch 2007, p. 23-24

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 24

- ^ a b Patri-Arch 2007, p. 23

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 67

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 76

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 80

- ^ (en) David M. Cheney, "Diocese of Trois Rivières" archive, on Catholic-Hierarchy (accessed December 31st, 2012)

- ^ Nive Voisine, "Cooke, Thomas" archive, on Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, University of Toronto/Université Laval (accessed January 1st, 2013)

- ^ Nive Voisine, "Laflèche, Louis-François" archive, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, University of Toronto/Université Laval (accessed January 1st, 2013)

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 15-16

- ^ a b c Patri-Arch 2007, p. 16

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 89-92

- ^ Patri-Arch 2007, p. 92-95

Appendix edit

Bibliography edit

- Patri-Arch, Le mausolée des évêques de Trois-Rivières : Rapport d'évaluation patrimoniale, Québec, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, 2007, 104 p. (ISBN 978-2-550-60891-2, read online archive [PDF])

- France Vanlaethem, Patrimoine en devenir : l'architecture moderne du Québec, Les Publications du Québec, 2012, 250 p. (ISBN 978-2-551-25210-7, read online archive)

External links edit

- Architectural resources: Canadian Register of Historic Places Québec Cultural Heritage Directory

- Geography resources: Quebec Sites Database