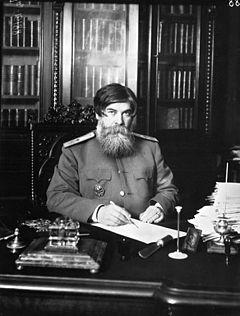

Vladimir Mikhailovich Bekhterev[1] (Russian: Влади́мир Миха́йлович Бе́хтерев, IPA: [ˈbʲextʲɪrʲɪf]; 20 January 1857 – 24 December 1927) was a Russian neurologist and the father of objective psychology. He is best known for noting the role of the hippocampus in memory, his study of reflexes, and Bekhterev’s disease. Moreover, he is known for his competition with Ivan Pavlov regarding the study of conditioned reflexes.

Vladimir Mikhailovich Bekhterev | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 January 1857 |

| Died | 24 December 1927 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | Russian, Soviet |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg University |

| Known for | Bekhterev’s disease Bekhterev–Jacobsohn reflex Bekhterev's mixture |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurology, psychology |

| Institutions | Military Medical Academy |

| Doctoral advisor | Wilhelm Wundt |

| Doctoral students | Victor Pavlovich Protopopov |

The sudden circumstances of his death has led to rumours that he died on the orders of Joseph Stalin. This is because Bekhterev performed a medical diagnosis of Stalin shortly before his death which was considered to be politically damaging to the position of the Soviet dictator.[2] This remains disputed among scholars due to the lack of direct evidence.[3]

Early life

editVladimir Bekhterev was born in Sorali, a village in the Vyatka Governorate of the Russian Empire between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains.[4] V. M. Bekhterev's father – Mikhail Pavlovich – was a district police officer; his mother, Maria Mikhailovna – was a daughter of a titular councilor, was educated at a boarding school which also provided lessons of music and the French language. Beside Vladimir they had two more sons in the family: Nikolai and Aleksandr, older than he by 6 and 3 years respectively. In 1864 the family moved to Vyatka, and within a year the head of the family died of tuberculosis when Bekhterev was still very young. While his childhood was not simple, Bekhterev did have the opportunity to attend Vyatka gymnasium in 1867, one of the oldest schools in Russia, as well as the Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg in 1873.[5] Then he studied in St. Petersburg Medicosurgical Academy where he worked under professor Jan Lucjan Mierzejewski (pl).[6] It was here where Bekhterev's interest in the disciplines of neuropathology and psychiatry were first sparked.[6]

Russia went to war with the Ottoman Empire in 1877. Bekhterev took time off from his studies in order to help the war effort by volunteering with an ambulance detachment. After the war, he returned to school. While attending school, Bekhterev worked as a junior doctor in the clinic of mental and nervous diseases at the Institutes of Medic’s Improvement. Here he began performing his experimental work. In 1878, Bekhterev graduated from the Medical and Surgery Academy of St. Petersburg with a degree similar to a Bachelor of Medicine.[5] After graduating, Bekhterev worked at the Psychiatric Clinic in St. Petersburg, where he was inspired to begin studying the anatomy and physiology of the brain, the area in which he would later make some of his most notable contributions.[6] It was also during this time that Bekhterev married Natalya Bazilevskaya.[5]

In 1880, Bekhterev began publishing his research. One of his earlier works described Russian social issues. In this paper, he wrote essays describing the individual characteristics of the Votyaks (Udmurts), a Finno-Ugric people under Russian rule who live in the Udmurt Republic between the rivers Vyatka and Kama.[7][8] Then, on 4 April 1881, Bekhterev successfully defended his doctoral thesis, "Clinical studies of temperature in some forms of mental disorders," and received his doctorate from the Medicosurgical Academy of St. Petersburg. This doctorate allowed Bekhterev to become a "private-docent" or associate professor, where he lectured on the diagnostics of nervous diseases.[5]

Contribution to neurology

editThroughout his career, Bekhterev conducted a large amount of research which greatly contributed to the current understanding of the brain. This research was described in works such as The Conduction Paths in the Brain and Spinal Cord, written in 1882, followed by a second edition written in 1896. In 1884 he published 58 scientific works about the functions of the brain. His extensive research led to an 18-month travel scholarship awarded to study and conduct research in both Germany and Paris.[5] On this trip he worked with and learned from a variety of notable contributors the field of science such as Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920), Paul Emil Flechsig (1847–1929), Theodor Meynert (1833–1892), Karl Friedrich Otto Westphal (1833–1890), Emil du Bois-Reymond (1818–1896), and Jean Martin Charcot (1825–1893).[6] Bekhterev's scholarship lasted until September 1885, after which, he returned to Russia and worked as the head of the Psychiatry Department at the University of Kazan until 1893.[9]

During his time at the University of Kazan, Bekhterev made some of his greatest contributions to neurological science. He established the first laboratory of experimental psychology in Russia in 1886 to study the nervous system and the structures of the brain. As a result of his research, Bekhterev believed that there were zones within the brain and each of these zones had a specific function. Moreover, because nervous disorders and mental disorders usually occur in conjunction with each other, he believed that there was no definite distinction between these disorders.[5] When conducting research at the University of Kazan, Bekhterev also identified Ankylosing Spondylitis or Bekhterev’s disease (more frequently spelled in English as Bechterew’s disease, following the German transliteration system for Russian names), a degenerative arthritis of the spine. As a result of his groundbreaking research, in 1891, Bekhterev was granted permission by the Kazan government to open and become the chairman of the Neurology Science Society.[5]

In 1893, Bekhterev left the University of Kazan to return to St. Petersburg Military Medical Academy to become the head to the Department of Nervous and Mental Diseases where he worked with Alexandre Dogiel. Here he continued his contribution to neurological research by organizing the first Russian neurosurgical operating room to specialize in neurosurgery. While Bekhterev never performed any surgeries himself, he was highly involved in the diagnostics of neurological diseases, eventually earning him the Full State Chancellor Title in 1894.[5]

Between 1894 and 1905 Bekhterev was very busy with his research. He completed between 14 and 24 scientific works per year and founded Nevrologicheski Vestnik (Neurology Bulletin) in 1893,[10] the first Russian journal on nervous disease.[5] Eventually, his work earned him the Baire’s Prize, awarded in December 1900, for the two volumes of his writing “Pathways of brain and bone marrow” in which he noted the role that the hippocampus plays in memory. Bekhterev's other writings include “Mind and Life,” a book written in 1902, which contained multiple volumes including “Foundations for Brain Functions Theory” written in 1903. “Foundations for Brain Functions Theory” described Bekhterev's views on the functions of the parts of the brain and the nervous system. It also suggested the Energetic Inhibition Theory which describes automatic responses (reflexes). This theory claims that there is an active energy in the brain which moves towards a center, and when this happens, the other parts of the brain are left in an inhibited state.[5] He published around 600 scientific papers. The most important works are "Suggestion and its Role in Social Life" (1899), "Consciousness and its Borders" (1888), "Psyche and Life" (1902),"Objective Psychology" (1907), "Subject Matter and Tasks of Social Psychology as an Objective Science" (1911), "Collective Reflexology" (1921) and "General Principles of Human Reflexology" (1926). An Autobiography was published at 1928, after his death. He founded other scientific journals: the “Archives of psychiatry, neurology and experimental psychology” (1896) and the “Bulletin of psychology, criminal anthropology and hypnotism” (1904).[11] “Suggestion and its role in social life” is a book of its time, the turning of the nineteenth to the twentieth century. On the question of the so-called psychic epidemic (folie à deux, folie à millions...), the author refers Calmeil, Landel, Laségue, Falret, Legrand de Saule, Regnard, Baillarger, Moreau de Tours and Morel. Gustave Le Bon and Gabriel Tarde are also mentioned on the psychology of the crowds.. He stresses the difference between suggestion and hypnosis Bekhterev was interested in phenomena of direct mental suggestion and made experiments to influence behavior of dogs at distance (José Manuel Jara, 2013).[11] Bekhterev's research on associated responses would become highly connected with the important area of psychology called Behaviorism. It also led to a long-standing rivalry with Ivan Pavlov, described in further detail below.

Objective psychology

editObjective psychology is based on the principle that all behavior can be explained by objectively studying reflexes. Therefore, behavior is studied through observable traits. This idea contrasted the more subjective views of psychology such as structuralism, which allowed for the use of tools such as introspection to study inner thoughts about personal experiences.

Objective Psychology would later become the basis of Reflexology, Gestalt Psychology, and especially behaviorism, an area which would later revolutionize the field of psychology and the manner in which the science of psychology is conducted. Bekhterev’s beliefs about how to best conduct research contributed to the rise of Soviet sociolinguistics from the ashes of völkerpsychologie and the Journal of the History of the behavioral Sciences.

Other contributions

editBekhterev founded the Psychoneurological Institute at the St. Petersburg State Medical Academy; however, he was forced to resign in 1913 as a professor at the Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg. He was reinstated in 1918 following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and became the chairperson for the Department of Psychology and Reflexology at the University of Petrograd in St. Petersburg as well as established the Institute of Studying Brain Mental Activities.[5]

In 1921 he was involved in organising the First Conference on Scientific Organization of Labour. He was critical of Taylorism arguing that "The ultimate ideal of the labour problem is not in it, but is in such organisation of the labour process that would yield a maximum of efficiency coupled with a minimum of health hazards, absence of fatigue and a guarantee of the sound health and all round personal development of the working people."[12]

During his time away from teaching, Bekhterev worked to open an orphanage, complete with both a kindergarten and school, for refugee children from the western regions of Russia. He also participated in creating health services in the "young country" of Russia.[5]

Ensuing from his doctrine of reflex arc, Bekhterev postulated the impact of social conditions on mental health. Thus, he demanded the improve of social conditions to improve mental health and to reduce crime.[13]

Rivalry with Ivan Pavlov

editBoth Ivan Pavlov and Bekhterev independently developed a theory of conditioned reflexes which describe automatic responses to the environment. What was called association reflex by Bekhterev is called the conditioned reflex by Pavlov, although the two theories are essentially the same. Because John Watson discovered the salivation research completed by Pavlov, this research was incorporated into Watson’s famous theory of Behaviorism, making Pavlov a household name. While Watson used Pavlov’s research to support his Behaviorist claims, closer inspection shows that in fact, Watson’s teachings are better supported by Bekhterev’s research.[14]

Bekhterev was familiar with Pavlov’s work and had multiple criticisms. According to Bekhterev, one of Pavlov’s major research flaws included using a saliva method. He found fault with this method because it could not be easily used on humans. In contrast, Bekhterev's method of studying this association (conditioned) reflex using mild electrical stimulation to examine motor reflexes was able to demonstrate the existence of this reflex in humans. Bekhterev also questioned using acid to encourage saliva from the animals. He felt that this practice may contaminate the results of the experiment. Finally, Bekhterev criticized Pavlov’s method by stating that the secretory reflex is unimportant and unreliable. If the animal is not hungry then food may not elicit the desired response, acting as evidence of the method’s unreliability.[15] Pavlov however was not without his own criticisms of Bekhterev, stating that Bekhterev’s laboratory was poorly controlled.[6]

Death

editAccording to Moroz (1989)[16] and Shereshevsky (1992),[17] mystery surrounds the death of Bekhterev. Bekhterev was a co-founder of the First All-Russian Congress of Neurologists and Psychiatry, held in December 1927 in Moscow, and was appointed as an Honorary President of the Congress. On 23 December 1927, after having lectured on child neurology at the Congress, Bekhterev went to the Kremlin to examine Joseph Stalin. About 3 hours later he came back to the Congress for a meeting and said to some colleagues there: "I have just examined a paranoiac with a short, dry hand."[18] The day after, Bekhterev suddenly died, causing speculation that he was poisoned by Stalin as revenge for the diagnosis.[16][19]

Bekhterev’s regular activities in the autumn and winter months of 1927, and even up to the last days of his life, showed no indications of worsening health despite the scientist’s more than 70 years of age.

— Shereshevsky A. M., The Mystery of the Death of V. M. Bekhterev [17]

Moreover, after Bekhterev's death, Stalin had Bekhterev's name and all of his works removed from Soviet textbooks.[4]

Legacy

editVladimir Bekhterev's contributions to science and specifically psychology were impressive. Bekhterev was a force in the science of neurology; greatly expanding knowledge on how the brain works as well as the parts of the brain. For instance, his research on the hippocampus allowed for the understanding of one of the most central portions of the brain vital to the function of memory. Moreover, his influence to psychology was immeasurable. Bekhterev’s works laid the groundwork for the future of psychology. His ideas regarding Objective psychology as well as his views on reflexes were a cornerstone of behaviorism.

According to a study conducted in 2015, Vladimir Bekhterev included in "Russia team on medicine". This list includes fifty-three famous Russian medical scientists from the Russian Federation, the Soviet Union, and the Russian Empire who were born in 1757—1950. Physicians of all specialities listed here. Among them Vladimir Demikhov, Sergei Korsakoff, Ivan Pavlov, Nikolay Pirogov, Victor Skumin.[20][21]

Only two know the mystery of brain: God and Bekhterev.

Overview of general findings

editParts of the Brain:[6]

- Bekhterev’s Acromial Reflex: a deep muscle reflex

- Bekhterev’s Disease: An autoimmune disease characterized by arthritis, inflammation, and eventual immobility of joints

- Bekhterev’s Nucleus: The superior nucleus of the vestibular nerve

- Bekhterev’s Nystagmus: Nystagmus that develops after the destruction of the canals of the inner ear

- Bekhterev’s Pectoralis Reflex: A reflex that extends the Pectoralis major muscle

- Bekhterev’s Reflex: Three reflexes described by Bekhterev concerning the eye, face and abdominal muscles

- Bekhterev’s Reflex I: Dilatation of the pupil upon exposure to light

- Bekhterev’s Reflex II: Scapulohumeral reflex

- Bekhterev’s Reflex of Eye: Areflex of the contraction of the M. orbicularis oculi

- Bekhterev’s Reflex of Hand: The hand-flexor phenomena

- Bekhterev’s Reflex of the Heel: Toe-flexion reflex

- Bekhterev-Jacobsohn reflex: A finger flexion reflex which corresponds with the Bekhterev-Mendel foot reflex

- Kaes-Bekhterev layer (also appears as stria, line or band of Bechterew).[22]

Other Accomplishments:

- Bekhterev’s Nucleus (Superior vestibular nucleus)[4]

- Bekhterev’s Disease: Numbness of the spine[4]

- Over 800 publications[4]

- Reflexology: objective study of human behavior that studies the relationship between environmental stimuli and overt behavior[15]

- Bekhterev’s Mixture: a medicine with a sedative effect.

Publications

edit- "Гипноз. Внушение. Телепатия (Монография)", В. М. Бехтерев, издательство "Мысль", г. Москва, 1994 г. ISBN 5-244-00549-9 (in Russian)

- José Manuel Jara Preface of V. M. Bekhterev "Suggestion and its Role in Social Life" Italian edition, Psichiatria e Territorio, 2013

Further reading

edit- Kizilova, Anna. "Vladimir Bekhterev, the World-Famous Russian Neurologist". Russia-InfoCentre.

- Shereshevsky A. M. (1992). "THE PAST AND PRESENT THROUGH THE EYES OF PSYCHIATRISTS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS: The Mystery of the Death of V. M. Bekhterev". The Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.: 83–87. ISBN 9780880486675. ISSN 1064-6930.

See also

edit- Bekhterev Research Institute

- Doctors' plot

- Dmitry Pletnyov (doctor) - Soviet doctor that performed a clinical diagnosis of Stalin and then was later executed in 1941.

- The Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology

Notes

edit- ^ Also transliterated Bechterev

- ^ Daniels, Harry; Cole, Michael; Wertsch, James V. (30 April 2007). The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky. Cambridge University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-83104-8.

- ^ Shiraev, Eric (4 February 2014). A History of Psychology: A Global Perspective. SAGE Publications. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-4833-2395-4.

- ^ a b c d e f PsychiatryOnline | American Journal of Psychiatry | Vladimir Bekhterev, 1857–1927

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Russia-InfoCentre :: Vladimir Bekhterev world-famous Russian neurologist :: people

- ^ a b c d e f Whonamedit – Vladimir Mikhailovich Bekhterev

- ^ "Этнографические очерки Бехтерева". vyatskaya-eparhia.ru. Retrieved 2024-07-21.

- ^ Бехтерев, В. (1880). Вотяки, их история и современное состояние: бытовые и этнографические очерки. Вестник Европы: журнал истории, политики, литературы. Vol. 8. Санкт-Петербург.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vladimir Bekhterev (Russian psychiatrist) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Nevrologicheski Vestnik: The History of the Journal

- ^ a b Preface by José Manuel Jara of :V. M. Bekhterev "Suggestion and its Role in Social Life" Italian edition Psichiatria e Territorio, 2013

- ^ Neville Moray (2005), Ergonomics: The history and scope of human factors, Routledge, ISBN 9780415322577, OCLC 54974550, OL 7491513M, 041532257X

- ^ Engmann B. Social issues relating to Vladimir Bekhterev's concept of reflexology: a hitherto underestimated aspect of his work. History of Psychiatry. 2024 Sep;35(3-4):347-354. doi: 10.1177/0957154X241254224.

- ^ Hergenhahn, B.R. (2009). An Introduction to the History of Psychology, Sixth Edition. Behaviorism (pp. 394–397). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- ^ a b Hergenhahn, B.R. (2009). An Introduction to the History of Psychology, Sixth Edition. Behaviorism (pp. 394–397). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- ^ a b Moroz, Oleg (1989). "The Last Diagnosis: A Plausible Account That Needs Further Verification". Soviet Review (6 ed.). pp. 82–102.

- ^ a b Shereshevsky, A. M. (1992). "The Mystery of the Death of V. M. Bekhterev". The Bekhterev Review of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.: 84.

- ^ Kesselring, J. (August 2011). "Vladimir Mikhailovic Bekhterev (1857–1927): Strange Circumstances Surrounding the Death of the Great Russian Neurologist". European Neurology. 66 (1): 14–17. doi:10.1159/000328779. PMID 21701175.

- ^ Turner, Matthew D. (March 2023). "Tyrant's End: Did Joseph Stalin Die From Warfarin Poisoning?". Cureus. 15 (3): e36265. doi:10.7759/cureus.36265. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 10105823. PMID 37073203.

- ^ "Сборная России по медицине" [Russia team on medicine]. Medportal.ru. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ "Сборная России по медицине" [Russia team on medicine]. Farm.tatarstan.ru. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ^ Stedman's Medical Eponyms