Lullubi Kingdom 𒇻𒇻𒉈𒆠 | |

|---|---|

| 2300 BC–675 BC | |

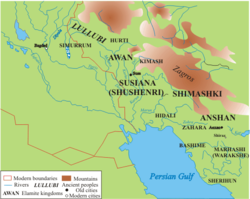

Territory of the Lullubi in the Mesopotamia area. | |

| Common languages | Unclassified Akkadian (inscriptions) |

| Religion | Mesopotamian religions |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Antiquity |

• Established | 2300 BC |

• Disestablished | 675 BC |

| Today part of | Iraq Iran |

Lullubi, Lulubi (Akkadian: 𒇻𒇻𒉈: Lu-lu-bi, Akkadian: 𒇻𒇻𒉈𒆠: Lu-lu-biki "Country of the Lullubi"), more commonly known as Lullu,[1][2][3][4] were a group of tribes during the 3rd millennium BC, from a region known as Lulubum, now the Sharazor plain of the Zagros Mountains of modern Iraqi Kurdistan, and the Kermanshah Province of Iran. Lullubi was neighbour and sometimes ally with the Simurrum kingdom.[5] Frayne (1990) identified their city Lulubuna or Luluban with the region's modern Iraqi town of Halabja.

The language of the Lullubi is regarded as an unclassified language[6] because it is unattested. The term Lullubi though, appears to be of Hurrian origin.[7]

Historical references

editLegends

editThe early Sumerian legend "Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird", set in the reign of Enmerkar of Uruk, alludes to the "mountains of Lulubi" as being where the character of Lugalbanda encounters the gigantic Anzû bird while searching for the rest of Enmerkar's army en route to siege Aratta.

Akkadian empire and Gutian dynasty

editLullubum appears in historical times as one of the lands Sargon the Great subjugated within his Akkadian Empire, along with the neighboring province of Gutium, which was probably of the same origin as the Lullubi. Sargon's grandson Naram Sin defeated the Lullubi and their king Satuni, and had his famous victory stele made in commemoration:

"Naram-Sin the powerful . . . . Sidur and Sutuni, princes of the Lulubi, gathered together and they made war against me."

— Akkadian inscription on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin.[8]

After the Akkadian Empire fell to the Gutians, the Lullubians rebelled against the Gutian king Erridupizir, according to the latter's inscriptions:

Ka-Nisba, king of Simurrum, instigated the people of Simurrum and Lullubi to revolt. Amnili, general of [the enemy Lullubi]... made the land [rebel]... Erridu-pizir, the mighty, king of Gutium and of the four quarters hastened [to confront] him... In a single day he captured the pass of Urbillum at Mount Mummum. Further, he captured Nirishuha.

— Inscription R2:226-7 of Erridupizir.[9]

Neo-Sumerian Empire

editFollowing the Gutian period, the Neo-Sumerian Empire (Ur-III) ruler Shulgi is said to have raided Lullubi at least 9 times; by the time of Amar-Sin, Lullubians formed a contingent in the military of Ur, suggesting that the region was then under Neo-Sumerian control.

Another famous rock relief depicting the Lullubian king Anubanini with the Assyrian-Babylonian goddess Ishtar, captives in tow, is now thought to date to the Ur-III period; however, a later Babylonian legendary retelling of the exploits of Sargon the Great mentions Anubanini as one of his opponents.

Babylonian and Assyrian interactions

editIn the following (second) millennium BC, the term "Lullubi" or "Lullu" seems to have become a generic Babylonian/Assyrian term for "highlander", while the original region of Lullubi was also known as Zamua. However, the "land of Lullubi" makes a reappearance in the late 12th century BC, when both Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon (in c. 1120 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser I of Assyria (in 1113 BC) claim to have subdued it. Neo-Assyrian kings of the following centuries also recorded campaigns and conquests in the area of Lullubum / Zamua. Most notably, Ashur-nasir-pal II had to suppress a revolt among the Lullubian / Zamuan chiefs in 881 BC, during which they constructed a wall in the Bazian pass (between modern Kirkuk and Sulaymaniyah) in a failed attempt to keep the Assyrians out.

They were said to have had 19 walled cities in their land, as well as a large supply of horses, cattle, metals, textiles and wine, which were carried off by Ashur-nasir-pal. Local chiefs or governors of the Zamua region continued to be mentioned down to the end of Esarhaddon's reign (669 BC).

Representations

editIn depictions of them, the Lullubi are represented as warlike mountain people.[12] The Lullubi are often shown bare-chested and wearing animal skins. They have short beards, their hair is long and worn in a thick braid, as can be seen on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin.[11]

Rulers

editRulers of the Lullubi kingdom:[13][14]

- Immashkush (c. 2400 BC)[15]

- Anubanini (c. 2350 BC) he ordered to make an inscription on the rock near Sar-e Pol-e Zahab.[16]

- Satuni (c. 2270 BC contemporary with Naram-Sin king of Akkad and Khita king of Awan)

- Irib (c. 2037 BC)

- Darianam (c. 2000 BC)

- Ikki (precise dates unknown)[16]

- Tar ... duni (precise dates unknown) son of Ikki. His inscription is found not far from the inscription of Anubanini.[16]

- Nur-Adad (c. 881 – 880 BC)

- Zabini (c. 881 BC)

- Hubaia (c. 830 BC) vassal of Assyrians

- Dada (c. 715 BC)

- Larkutla (c. 675 BC)

Lullubi rock reliefs

editVarious Lullubian reliefs can be seen in the area of Sar-e Pol-e Zohab, the best preserved of which is the Anubanini rock relief. They all show a ruler trampling an enemy, and most also show a deity facing the ruler. Another relief can be found about 200 meters away, in a style similar to the Anubanini relief, but this time with a beardless ruler.[17] The attribution to a specific ruler remains uncertain.[17][18]

Anubanini rock relief

edit-

The relief is located on the top of a cliff towering over the village of Sarpol-e Zahab. A second relief (Parthian Empire period) appears below.

-

Prisoners of the Lullubis (detail).[17]

-

Prisoners of the Lullubis and their king (detail).[17]

-

Prisoner king (detail). He appears to be wearing a crown.[17]

-

Anubanini rock relief Akkadian inscription.[17]

Other Lullubi reliefs

edit-

Sar-e Pol-e Zahab, relief III. Beardless warrior trampling a foe, facing a goddess.[19]

-

Sar-e Pol-e Zahab, relief IV. Beardless warrior trampling a foe, facing a goddess.[19]

-

Detail, a dead or dying Lullubian warrior. Darband-i Gawr rock-relief, Mt. Qaradagh, Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, 2200-2000 BCE

-

Detail, a dead or dying Lullubian warrior, Darband-i Gawr rock-relief, Mt. Qaradagh, Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, 2200-2000 BCE

See also

editReferences

editNotes

editCitations

edit- ^ Eidem, Jesper; Læssøe, Jørgen (1992). The Shemshāra Archives 2: The Administrative Texts. Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. pp. 22, 51–54. ISBN 978-87-7304-227-4.

- ^ Speiser, Ephraim Avigdor (2017-01-30). Mesopotamian Origins: The Basic Population of the Near East. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-5128-1881-9.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (2017-10-03). Language Isolates. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-317-61091-5.

- ^ Potts, Daniel T. (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-19-933079-9.

- ^ Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge. pp. 115–116. ISBN 9781134520626.

- ^ "The Languages of the Ancient Near East (in A Companion to the Ancient Near East, 2nd ed., 2007)".

- ^ Tischler 1977–2001: vol. 5/6: 70–71. On the Lullubeans in general, see Klengel 1987–1990; Eidem 1992: 50–4.

- ^ Babylonian & Oriental Record. 1895. p. 27.

- ^ Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge. pp. 115–116. ISBN 9781134520626.

- ^ "Louvre Museum Official Website". cartelen.louvre.fr.

- ^ a b "The hair of the Lullubi is long and worn in a thick braid. They wear animal skins, while the Akkadian soldiers wear the proper attire for battle, helmets and military tunics." in Bahrani, Zainab (2008). Rituals of War: The Body and Violence in Mesopotamia. Zone Books. p. 109. ISBN 9781890951849.

- ^ Bury, John Bagnell; Cook, Stanley Arthur; Adcock, Frank Ezra (1975). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Egyptian and Hittite empires to c. 1000 B.C. University Press. p. 505. ISBN 9780521086912.

- ^ Qashqai, 2011.

- ^ Legrain, 1922; Cameron, 1936; D’yakonov, 1956; The Cambridge History of Iran; Hinz, 1972; The Cambridge Ancient History; Majidzadeh, 1991; Majidzadeh, 1997.

- ^ Cameron, George G. (1936). History of Early Iran (PDF). The University of Chicago Press. p. 35.

- ^ a b c Cameron, George G. (1936). History of Early Iran (PDF). The University of Chicago Press. p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. p. 123. ISBN 9781438453255.

- ^ Vanden Berghe, Louis. Relief Sculptures de Iran Ancien. pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b c d Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781438453255.

- ^ Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781438453255.

- ^ Frayne, Douglas (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC). University of Toronto Press. pp. 707 ff. ISBN 9780802058737.

Sources

editBibliography

editJournals

editExternal links

editFurther reading

editGeography

editLanguage

edit- Black, Jeremy Allen; Baines, John Robert; Dahl, Jacob L.; Van De Mieroop, Marc. Cunningham, Graham; Ebeling, Jarle; Flückiger-Hawker, Esther; Robson, Eleanor; Taylor, Jon; Zólyomi, Gábor (eds.). "ETCSL: The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Faculty of Oriental Studies (revised ed.). United Kingdom. Retrieved 2022-09-23.

The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (ETCSL), a project of the University of Oxford, comprises a selection of nearly 400 literary compositions recorded on sources which come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq) and date to the late third and early second millennia BCE.

- Renn, Jürgen; Dahl, Jacob L.; Lafont, Bertrand; Pagé-Perron, Émilie (2022) [1998]. "CDLI: Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative" (published 1998–2022). Retrieved 2022-09-23.

Images presented online by the research project Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI) are for the non-commercial use of students, scholars, and the public. Support for the project has been generously provided by the Mellon Foundation, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the Institute of Museum and Library Services (ILMS), and by the Max Planck Society (MPS), Oxford and University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); network services are from UCLA's Center for Digital Humanities.

- Sjöberg, Åke Waldemar; Leichty, Erle; Tinney, Steve (2022) [2003]. "PSD: The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary" (published 2003–2022). Retrieved 2022-09-23.

The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary Project (PSD) is carried out in the Babylonian Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. It is funded by the NEH and private contributions. [They] work with several other projects in the development of tools and corpora. [Two] of these have useful websites: the CDLI and the ETCSL.