| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛˌdrɒksiproʊˈdʒɛstəroʊn ˈæsɪteɪt/ me-DROKS-ee-proh-JES-tər-ohn ASS-i-tayt[1] |

| Trade names | Provera, Depo-Provera, Depo-SubQ Provera 104, Curretab, Cycrin, Farlutal, Gestapuran, Perlutex, Veramix, others[2] |

| Other names | MPA; DMPA; methylhydroxy |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604039 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, intramuscular injection, subcutaneous injection |

| Drug class | Progestogen; progestin; antigonadotropin; steroidal antiandrogen |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | By mouth: ~100%[3][4] |

| Protein binding | 88% (to albumin)[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver (hydroxylation (CYP3A4), reduction, conjugation)[5][3][9] |

| Elimination half-life | By mouth: 12–33 hours[5][3] IM (aq. susp.): ~50 days[6] SC (aq. susp.): ~40 days[7] |

| Duration of action | 3 months (depo injection)[8] |

| Excretion | Urine (as conjugates)[5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Chemical and physical data | |

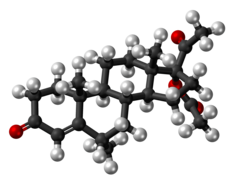

| Formula | C24H34O4 |

| Molar mass | 386.532 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 207 to 209 °C (405 to 408 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in injectable form and sold under the brand name Depo-Provera among others, is a hormonal medication of the progestin type.[10][3] It is used as a method of birth control and as a part of menopausal hormone therapy.[10][3] It is also used to treat endometriosis, abnormal uterine bleeding, abnormal sexuality in males, and certain types of cancer.[10] The medication is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen.[12][13] It is taken by mouth, used under the tongue, or by injection into a muscle or fat.[10]

Common side effects include menstrual disturbances such as absence of periods, abdominal pain, and headaches.[10] More serious side effects include bone loss, blood clots, allergic reactions, and liver problems.[10] Use is not recommended during pregnancy as it may harm the baby.[10] MPA is an artificial progestogen, and as such activates the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progesterone.[3] It also has weak glucocorticoid activity and very weak androgenic activity but no other important hormonal activity.[3][14] Due to its progestogenic activity, MPA decreases the body's release of gonadotropins and can suppress sex hormone levels.[15] It works as a form of birth control by preventing ovulation.[10]

MPA was discovered in 1956 and was introduced for medical use in the United States in 1959.[16][17][10] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[18] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.60–1.60 per vial.[19] In the United Kingdom this dose costs the NHS about £6.[20] In the United States it costs less than $25 a dose as of 2015.[21] MPA is the most widely used progestin in menopausal hormone therapy and in progestogen-only birth control.[22][23] DMPA is approved for use as a form of long-acting birth control in more than 100 countries.[24][25] In 2017, it was the 222nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[26][27]

References edit

- ^ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-03. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 638–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ^ a b Schindler AE, Campagnoli C, Druckmann R, Huber J, Pasqualini JR, Schweppe KW, Thijssen JH (2008). "Classification and pharmacology of progestins". Maturitas. 61 (1–2): 171–80. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.11.013. PMID 19434889.

- ^ a b c "Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Depo_Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "depo-subQ Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ a b "MEDROXYPROGESTERONE injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Stanczyk FZ, Bhavnani BR (September 2015). "Reprint of "Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: Is it safe?"". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 153: 151–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.08.013. PMID 26291834.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-03. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 2113–2114. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ^ Kemppainen JA, Langley E, Wong CI, Bobseine K, Kelce WR, Wilson EM (March 1999). "Distinguishing androgen receptor agonists and antagonists: distinct mechanisms of activation by medroxyprogesterone acetate and dihydrotestosterone". Molecular Endocrinology. 13 (3): 440–54. doi:10.1210/mend.13.3.0255. PMID 10077001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Genazzani AR (15 January 1993). Frontiers in Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. Taylor & Francis. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-85070-486-7. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016.

- ^ Stanley M. Roberts (7 May 2013). Introduction to Biological and Small Molecule Drug Research and Development: Chapter 12. Hormone replacement therapy. Elsevier Science. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-12-806202-9. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

[...] medroxyprogesterone acetate, also known as Provera® (discovered simultaneously by Searle and Upjohn in 1956) [..]

- ^ Sneader, Walter (2005). "Chapter 18: Hormone analogs". Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. p. 204. ISBN 0-471-89980-1.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ British National Formulary : BNF 69 (69th ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-85711-156-2.

- ^ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 363. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ^ A. Wayne Meikle (1 June 1999). Hormone Replacement Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 383–. ISBN 978-1-59259-700-0. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction (World Health Organization); World Health Organization (2002). Research on Reproductive Health at WHO: Biennial Report 2000-2001. World Health Organization. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-92-4-156208-9. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bagade O, Pawar V, Patel R, Patel B, Awasarkar V, Diwate S (2014). "Increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception: safe, reliable, and cost-effective birth control" (PDF). World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 3 (10): 364–392. ISSN 2278-4357. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ^ Sulochana Gunasheela (14 March 2011). Practical Management of Gynecological Problems. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-93-5025-240-6. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.