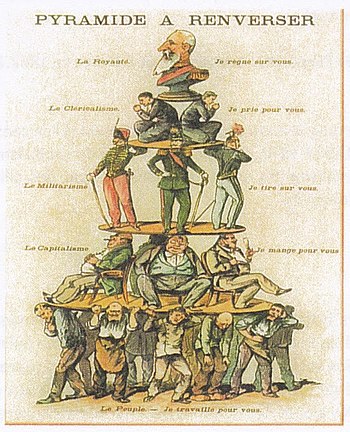

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals.[1] Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally related groups or sets of roles, with different functions, meanings, or purposes. Examples of social structure include family, religion, law, economy, and class. It contrasts with "social system", which refers to the parent structure in which these various structures are embedded. Thus, social structures significantly influence larger systems, such as economic systems, legal systems, political systems, cultural systems, etc. Social structure can also be said to be the framework upon which a society is established. It determines the norms and patterns of relations between the various institutions of the society.

Since the 1920s, the term has been in general use in social science,[2] especially as a variable whose sub-components needed to be distinguished in relationship to other sociological variables, as well as in academic literature, as result of the rising influence of structuralism. The concept of "social stratification", for instance, uses the idea of social structure to explain that most societies are separated into different strata (levels), guided (if only partially) by the underlying structures in the social system. It is also important in the modern study of organizations, as an organization's structure may determine its flexibility, capacity to change, etc. In this sense, structure is an important issue for management.

On the macro scale, social structure pertains to the system of socioeconomic stratification (most notably the class structure), social institutions, or other patterned relations between large social groups. On the meso scale, it concerns the structure of social networks between individuals or organizations. On the micro scale, "social structure" includes the ways in which 'norms' shape the behavior of individuals within the social system. These scales are not always kept separate. For example, John Levi Martin has theorized that certain macro-scale structures are the emergent properties of micro-scale cultural institutions (i.e., "structure" resembles that used by anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss). Likewise, in ethnography, a recent study describes how indigenous social structure in the Republic of Panama changed macro social structures and impeded a planned Panama Canal expansion.[3] Marxist sociology has also historically mixed different meanings of social structure, though doing so by simply treating the cultural aspects of social structure as phenomenal of its economic aspects.

Social norms are believed to influence social structure through relations between the majority and the minority. As those who align with the majority are considered 'normal', and those who align with the minority are considered 'abnormal', majority-minority relations create a hierarchical stratification within social structures that favors the majority in all aspects of society.

History

editEarly history

editThe early study of social structures has considerably informed the study of institutions, culture and agency, social interaction, and history.

Alexis de Tocqueville was supposedly the first to use the term "social structure". Later, Karl Marx, Herbert Spencer, Ferdinand Tönnies, Émile Durkheim, and Max Weber would all contribute to structural concepts in sociology. The latter, for example, investigated and analyzed the institutions of modern society: market, bureaucracy (private enterprise and public administration), and politics (e.g. democracy).

One of the earliest and most comprehensive accounts of social structure was provided by Karl Marx, who related political, cultural, and religious life to the mode of production (an underlying economic structure). Marx argued that the economic base substantially determined the cultural and political superstructure of a society. Subsequent Marxist accounts, such as that of Louis Althusser, proposed a more complex relationship that asserted the relative autonomy of cultural and political institutions, and a general determination by economic factors only "in the last instance."[4]

In 1905, German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies published his study The Present Problems of Social Structure,[5] in which he argues that only the constitution of a multitude into a unity creates a "social structure", basing his approach on his concept of social will.

Émile Durkheim, drawing on the analogies between biological and social systems popularized by Herbert Spencer and others, introduced the idea that diverse social institutions and practices played a role in assuring the functional integration of society through assimilation of diverse parts into a unified and self-reproducing whole. In this context, Durkheim distinguished two forms of structural relationship: mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity. The former describes structures that unite similar parts through a shared culture, while the latter describes differentiated parts united through social exchange and material interdependence.[4]

As did Marx and Weber, Georg Simmel, more generally, developed a wide-ranging approach that provided observations and insights into domination and subordination; competition; division of labor; formation of parties; representation; inner solidarity and external exclusiveness; and many similar features of the state, religious communities, economic associations, art schools, and of family and kinship networks. However diverse the interests that give rise to these associations, the forms in which interests are realized may yet be identical.[6]

Later developments

editThe notion of social structure was extensively developed in the 20th century with key contributions from structuralist perspectives drawing on theories of Claude Lévi-Strauss, as well as feminist, marxist, functionalist (e.g. those developed by Talcott Parsons and followers), and a variety of other analytic perspectives.[7][8] Some follow Marx in trying to identify the basic dimensions of society that explain the other dimensions, most emphasizing either economic production or political power. Others follow Lévi-Strauss in seeking logical order in cultural structures. Still others, notably Peter Blau, follow Simmel in attempting to base a formal theory of social structure on numerical patterns in relationships—analyzing, for example, the ways in which factors like group size shape intergroup relations.[4]

The notion of social structure is intimately related to a variety of central topics in social science, including the relation of structure and agency. The most influential attempts to combine the concept of social structure with agency are Anthony Giddens' theory of structuration and Pierre Bourdieu's practice theory. Giddens emphasizes the duality of structure and agency, in the sense that structures and agency cannot be conceived apart from one another. This permits him to argue that structures are neither independent of actors nor determining of their behavior, but rather sets of rules and competencies on which actors draw, and which, in the aggregate, they reproduce. Giddens's analysis, in this respect, closely parallels Jacques Derrida's deconstruction of the binaries that underlie classic sociological and anthropological reasoning (notably the universalizing tendencies of Lévi-Strauss's structuralism). Bourdieu's practice theory also seeks a more subtle account of social structure as embedded in, rather than determinative of, individual behavior.[4]

Other recent work by Margaret Archer (morphogenesis theory),[9] Tom R. Burns and Helena Flam (actor-system dynamics theory and social rule system theory),[10][11] and Immanuel Wallerstein (World Systems Theory)[12] provide elaborations and applications of the sociological classics in structural sociology.

Definitions and concepts

editAs noted above, social structure has been conceptualized as:

- the relationship of definite entities or groups to each other;

- the enduring patterns of behaviour by participants in a social system in relation to each other; and

- the institutionalised norms or cognitive frameworks that structure the actions of actors in the social system.

Institutional vs Relational

editFurthermore, Lopez and Scott (2000) distinguish between two types of structure:[8]

- Institutional structure: "social structure is seen as comprising those cultural or normative patterns that define the expectations of [sic] agents hold about each other's behaviour and that organize their enduring relations with each other."

- Relational structure: "social structure is seen as comprising the relationships themselves, understood as patterns of causal interconnection and interdependence among agents and their actions, as well as the positions that they occupy."

Micro vs Macro

editSocial structure can also be divided into microstructure and macrostructure:

- Microstructure: The pattern of relations between most basic elements of social life, that cannot be further divided and have no social structure of their own (e.g. pattern of relations between individuals in a group composed of individuals, where individuals have no social structure; or a structure of organizations as a pattern of relations between social positions or social roles, where those positions and roles have no structure by themselves).

- Macrostructure: The pattern of relations between objects that have their own structure (e.g. a political social structure between political parties, as political parties have their own social structure).

Other types

editSociologists also distinguish between:

- Normative structures: pattern of relations in a given structure (organization) between norms and modes of operations of people of varying social positions

- Ideal structures: pattern of relations between beliefs and views of people of varying social positions

- Interest structures: pattern of relations between goals and desires of people of varying social positions

- Interaction structures: forms of communication of people of varying social positions

Modern sociologists sometimes differentiate between three types of social structures:

- Relation structures: family or larger family-like clan structures

- Communication structures: structures in which information is passed (e.g. in organizations)

- Sociometric structures: structures of sympathy, antipathy, and indifference in organizations. This was studied by Jacob L. Moreno.

Social rule system theory reduces the structures of (3) to particular rule system arrangements, i.e. the types of basic structures of (1 and 2). It shares with role theory, organizational and institutional sociology, and network analysis the concern with structural properties and developments and at the same time provides detailed conceptual tools needed to generate interesting, fruitful propositions and models and analyses.

Origin and development of structures

editSome believe that social structure develops naturally, caused by larger systemic needs (e.g. the need for labour, management, professional, and military functions), or by conflicts between groups (e.g. competition among political parties or élites and masses). Others believe that structuring is not a result of natural processes, but of social construction. Research from scholars Nicole M. Stephens and Sarah Townsend demonstrated that the cultural mismatch between institutions' ideals of independence and the interdependence common among working-class individuals can hinder workers' opportunities to succeed.[13] In this sense, social structure may be created by the power of élites who seek to retain their power, or by economic systems that place emphasis upon competition or upon cooperation.

Ethnography has contributed to understandings about social structure by revealing local practices and customs that differ from Western practices of hierarchy and economic power in its construction.[3]

Social structures can be influenced by individuals, but individuals are often influenced by agents of socialization (e.g., the workplace, family, religion, and school). The way these agents of socialization influence individualism varies on each separate member of society; however, each agent is critical in the development of self-identity.[14]

Critical implications

editThe notion of social structure may mask systematic biases, as it involves many identifiable sub-variables (e.g. gender). Some argue that men and women who have otherwise equal qualifications receive different treatment in the workplace because of their gender, which would be termed a "social structural" bias, but other variables (such as time on the job or hours worked) might be masked. Modern social structural analysis takes this into account through multivariate analysis and other techniques, but the analytic problem of how to combine various aspects of social life into a whole remains.[15][16]

Development of Individualism

editSociologists such as Georges Palante have written on how social structures coerce our individuality and social groups by shaping the actions, thoughts, and beliefs of every individual human being. In terms of agents of socialization, social structures are slightly influenced by individuals but individuals are more greatly influenced by them. Some examples of these agents of socialization are the workplace, family, religion, and school. The way these agents of socialization influence your individualism varies on each one; however, they all play a big role in your self-identity development. Agents of socialization can also affect how you see yourself individually or as part of a collective. Our identities are constructed through social influences that we encounter in our daily lives. [17] The way you are raised to view your individuality can hinder your ability to succeed by capping your abilities or it could become an obstacle in certain environments in which individuality is embraced like colleges or friend groups. [17]

Related concepts

edit- Agency (sociology)

- Base and superstructure

- Cognitive social structures

- Conflict theory

- Formative context

- Morphological analysis

- Norm (sociology)

- Political structure

- Power (social and political)

- Socialization

- Social Model

- Social network

- Social order

- Social reproduction

- Social space

- Social structure of the United States

- Sociotechnical systems theory

- Structural functionalism

- Structural violence

- Structure and agency

- Systems theory

- Technological determinism

- Theory of structuration

- Values

Related theorists

editReferences

edit- ^ Olanike, Deji (2011). Gender and Rural Development By. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 71. ISBN 9783643901033.

- ^ Merton, Robert. 1938. "Social Structure and Anomie." American Sociological Review 3(5):672–82.

- ^ a b Muller-Schwarz, Nina K. (2015). The Blood of Victoria no Lorenzo: An Ethnography of the Solos of Northern Coco Province. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Press.

- ^ a b c d Calhoun, Craig. 2002. "Social Structure." Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Tönnies, Ferdinand. 1905. "The Present Problems of Social Structure." American Journal of Sociology 10(5):569–88.

- ^ Crothers, Charles. 1996. Social Structure. London: Routledge.

- ^ Blau, Peter M., ed. 1975. Approaches to the Study of Social Structure. New York: The Free Press.

- ^ a b Lopez, J. and J. Scott. 2000. Social Structure. Buckingham: Open University Press. ISBN 9780335204960. OCLC 43708597. p. 3.

- ^ Archer, Margaret S. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Burns, Tom R., and H. Flam. 1987. The Shaping of Social Organization: Social Rule System Theory with Applications. London: SAGE.

- ^ Flam, Helena, and Marcus Carson, eds. 2008. Rule System Theory: Applications and Explorations. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Publishers. ISBN 9783631575963.

- ^ Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2004. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham: Duke University Press.

- ^ Stephens, Nicole M.; Townsend, Sarah (2017-05-22). "Research: How You Feel About Individualism Is Influenced by Your Social Class". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

The mismatch between institutions' cultural ideal of independence and the interdependent norms common among working-class individuals can reduce their opportunity to succeed.

- ^ Genner, Sarah; SÜSS, Daniel (2017). "Socialization as Media Effect" (PDF). In Rössler, Patrick (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Aberration, et al. 2000

- ^ Jary, D., and J. Jary, eds. 1991. "Social structure." The Harper Collins Dictionary of Sociology. New York: Harper Collins.

- ^ a b Halasz, Judith (2022). Social Structure and The Individual. PanOpen Telegrapher. pp. 7–17.

Further reading

edit- Abercrombie, Nicholas, Stephan Hill, and Bryan S. Turner. 2000. "Social structure." Pp. 326–7 in The Penguin Dictionary of Sociology (4th ed.). London: Penguin.

- Eloire, Fabien. 2015. "The Bourdieusian Conception of Social Capital: A Methodological Reflection and Application." Forum for Social Economics 47 (3): 322–41

- Murdock, George (1949). Social Structure. New York: MacMillan.

- Porpora, Douglas V. 1987. The Concept of Social Structure. New York: Greenwood Press.

- — 1989. "Four Concepts of Social Structure." Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 19 (2): 195–211.

- Sewell, William H. (1992). "A Theory of Structure: Duality, Agency, and Transformation". American Journal of Sociology. 98 (1): 1–29.

- Smelser, Neal J. 1988. "Social structure." Pp. 103–209 in The Handbook of Sociology, edited by N. J. Smelser. London: SAGE.